Living Well with Chronic Illness

Americans value health and the capacity to live with a sense of physical, mental, and social well-being. For many, having health also implies access to social and personal resources that enable them to live well on a day-to-day basis (WHO, 1986). Generally, people tend to place less value on simply living longer if added years of life come without the security of health and well-being. Indeed, there is a limit to people’s willingness to accept physical and psychosocial discomfort or to compromise functional independence, the capacity to enjoy relationships with others, or financial security in exchange for longer life expectancy (Miller and Levy, 2000; Tengs et al., 1995).

Chronic diseases are long-term health conditions that threaten well-being and function in an episodic, continuous, or progressive way over many years of life (NCCDPHP, [a]; WHO, [a]). Not only have chronic diseases emerged as leading causes of death; they also represent enormous and growing causes of impairment and disability (WHO, 2004). Tremendous advances in public health and health care over the past century have extended average life expectancies, but these advances have been compromised by parallel increases in physical inactivity, unhealthful eating, obesity, tobacco use, and other chronic disease risk factors (McGinnis and Foege, 1993; Mokhad et al., 2004; WHO, 2009). As a result of this combination, more individuals are living longer but with one or more chronic illnesses (HHS, 2010). In fact, living for many years with a chronic disease is now common, and this presents a growing threat not only to population health but also to the nation’s economic and social welfare. Although much work is under way to address the burden of chronic disease, resources are limited

and the problem is growing. In this context, there is a clear danger that these efforts will prove unsuccessful unless they can be prioritized, aligned, and coordinated in a way that achieves the greatest benefit at a cost that is acceptable to society. Addressing the toll of all chronic diseases, from a population health perspective, is the subject of this report.

THE TIMELY RELEVANCE OF A PUSH TOWARD

LIVING WELL WITH CHRONIC ILLNESS

Chronic illnesses have always been a great burden not only to those living with them but also to their societies and cultures, taking a tremendous toll on welfare, economic productivity, social structures, and achievements. Individuals with chronic illnesses have historically sought varied healers and healing institutions in their communities to alleviate suffering, but over past centuries there were few management aids for severe and progressive conditions, and survivorship was often modest at best. This problem was exacerbated by frequent lack of access to supportive or palliative care, and death often came quickly. However, even in these unfortunate historical circumstances, the state, along with many nongovernmental organizations, played important roles in the response to chronic diseases, providing almshouses and hospitals for impoverished, disabled, and otherwise sick individuals who may not have had the fiscal or social resources to remain in the community or who had been ostracized from community life because of their conditions.

In the past century, extraordinary advances in developed countries in medicine and public health, as well as economic growth leading to more widely accessible social welfare programs, have changed the chronic disease landscape dramatically. Hygienic and sanitary advances have prevented many previously common diseases. Immunizations and clinical and community interventions have substantially controlled many past causes of chronic illness, such as tuberculosis and syphilis. Good progress in reducing tobacco use has occurred, even if incomplete. Pharmacotherapy has enabled most persons with chronic mental illnesses to be deinstitutionalized, even in the absence of prevention or cure. Although there is more work to do, chronic cardiovascular diseases have been diminished in many important ways. Importantly, additional therapeutic approaches have improved the function and overall health for some persons with chronic illnesses through advances in corrective surgery, new approaches in analgesia, better rehabilitation and physical and occupational therapy, improved nutrition management, and adaptation of home and community environments for functionally impaired persons.

Despite these advances, many community-wide problems with chronic diseases remain major public health concerns. Individuals with congenital

disabling conditions now survive longer into adulthood. Numerous important chronic diseases still have no known or controllable causes and continue unabated, such as mental illnesses, chronic skin conditions, inflammatory bowel diseases, collagen vascular diseases, and degenerative neurological illnesses. Chronic illnesses resulting from injuries or burns or from infectious agents (e.g., hepatitis B and C, HIV, H. pylori) also continue to take an important long-term toll on those affected. The control of many chronic illnesses among young and middle-aged adults, even with some important successes, has delayed the onset of these illnesses to older ages. Amid medical progress, enhanced population survival has also permitted the emergence of more degenerative illnesses at older ages, such as arthritis, dementia, and end-stage kidney disease. Moreover, the availability and application of more intensive medical therapies has increased treatment costs and the probability of adverse events. Some examples include deep vein thrombosis following joint replacement surgery for hip or knee arthritis; increases in type 2 diabetes during treatment with some common mental health medications; more cardiovascular events with intensive glucose lowering in some patients with diabetes; antibiotic resistant infections of kidney dialysis catheters; and increased risk of falls or fractures among frail elders treated with sedative-hypotic medications intended for improving sleep or reducing agitation.

In addition, some population risk factors for chronic diseases are going in the wrong direction. Obesity levels have increased dramatically, along with physical inactivity and unhealthful eating, accounting for a considerable proportion of prevalent chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (McGinnis and Foege, 1993; Mokdad et al., 2004). As a result, the average life expectancy for Americans living in most U.S. counties has decreased over the past decade relative to gains being made in other leading nations around the world (Kulkarni et al., 2011). Thus, in the modern era, the toll of chronic diseases on physical, mental, and social health, health care, and the economy continues to a problem of critical magnitude in America today (Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation, 2010; DeVol and Bedroussian, 2007; Michaud et al., 2006; NCCDPHP, 2009).

THE POPULATION HEALTH PERSPECTIVE

Taking a population health perspective means considering the magnitude and distribution of health outcomes from the viewpoint of societal groups or populations (Kindig, 2007). From such a perspective, genes, biology, behavior, and environment are all seen to interact in their impact on health and function. Older adults are biologically prone to being in poorer health than adolescents because of the physical and cognitive effects

of aging. Individuals can also inherit a higher probability of developing many illnesses, such as sickle cell anemia, breast cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. People interact with one another and their environments through behaviors that can also impact health. For example, a person who is physically inactive is more likely to develop obesity, depressive illness, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and many cancers (HHS, 1996). Conversely, an individual who quits smoking can reduce his or her risk of developing heart disease, chronic obstructive lung diseases, and many cancers. Social influences and the physical environments in which people are born, live, learn, play, work, and age influence health in important ways. Educational and job opportunities; poverty; social norms and attitudes; discrimination; social support; exposure to mass media and technologies, such as the internet or cell phones; transportation options; and access to healthy foods, safe physical activities, or health care services are all important examples of environmental conditions that play important roles in determining health and function.

CHRONIC DISEASES AND THEIR IMPACT

ON HEALTH AND FUNCTION

In 2005, 133 million Americans—almost half of all adults—had at least one chronic illness, causing 7 in 10 deaths in the United States each year (CDC, [a]). More than one in four Americans have concurrent multiple chronic conditions (two or more) (MCCs) (Anderson, 2010), including, for example, arthritis, asthma, chronic respiratory conditions, diabetes, heart disease, HIV infection, and hypertension. Regardless of the severity, pattern of effects, or duration of the disease, many diseases typically last at least a year, require ongoing medical attention, and limit activities of daily living (HHS, 2010).

“Morbidity” is a term commonly used to describe the burden of suffering, in terms of impairment or disability, caused by an illness or health condition. Morbidity can be measured at the individual level or summed to reflect the aggregate health of a population. Chronic diseases cause considerable population morbidity, which is reflected in often striking statistics regarding the frequency of various complications and subsequent high levels of health care utilization, health care costs, and missed days of work due to illness or disability. The degree of population morbidity caused by a chronic illness is often challenging to define, however, since some conditions are less common but lead to devastating consequences, whereas others affect millions of individuals in more subtle yet meaningful ways. Chronic illnesses also cause morbidity by impacting the quality of life of not only those who have the condition but also their families, friends, and caregivers. For society, chronic diseases take a large toll by imposing psychosocial stress,

lowering economic prosperity, and increasing costs in both the health care and the public health sector (DeVol and Bedroussian, 2007; Thorpe, 2006).

In terms of a toll on quality of life, chronic disease morbidity can be assessed along multiple dimensions, such as pain, fatigue, physical impairment, lack of sleep, emotional distress, and decreased social health, or as a summative effect across all of these dimensions (NIH, 2011). Not surprisingly, different chronic diseases also impact dimensions of health in varied ways. For example, both schizophrenia and rheumatoid arthritis have a dramatic impact on the quality of life of individuals and their caregivers, but the scope of those impacts is very different. Persons with schizophrenia must deal with the stigma and often relapsing and remitting symptoms of a lifelong mental illness, causing many to never reach such milestones as getting married, having children, forming strong relationships with family, or being gainfully employed. In contrast, persons with rheumatoid arthritis suffer a variable course of physical concerns, changes in role function, and loss of specific abilities that often increase over time. It is important to appreciate the many facets of chronic disease morbidity and to recognize that all chronic diseases, whether common or rare, are of considerable importance to those who are affected.

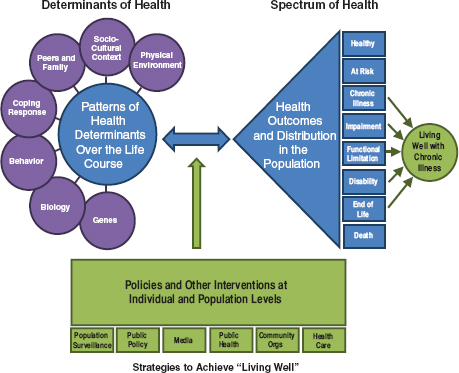

It is also important to recognize that the degree of impairment or disability imposed by a particular chronic illness is subject to change over time, as the illness’s course and the affected individual’s coping responses evolve. Some chronic diseases, such as arthritis or type 2 diabetes, begin to impact quality of life even prior to their diagnosis, by causing psychological stress or physical symptoms. Other diseases that are typically considered chronic, such as high blood pressure or prediabetes, may continue for years without symptoms or measurable signs of illness per se. Having these illnesses, however, can still cause various forms of impairment. For example, quality of life can be reduced by the added stress of coping with the diagnosis itself, as individuals must perform new and sometimes complex self-care behaviors or to engage more intensively in health services designed to treat or prevent complications of the condition. Moreover, despite even the best of intentions, therapies for chronic illnesses can have unintended consequences, such as increasing stress or physiological symptoms or even by causing direct harm. Many of these consequences are easily overlooked. The full spectrum of health and morbidity for persons with chronic illnesses has been depicted previously in several frameworks (Nagi, 1965). By combining these past frameworks in a way that highlights a perspective of population health along the full spectrum of health and morbidity, the committee constructed an integrated framework to serve as a reference for discussing which strategies are likely to offer the greatest promise to improve health for individuals living with chronic illness, depicted in Figure 1-1.

A key feature of this integrated framework is that a principal aim of

FIGURE 1-1 Integrated framework for living well with chronic illness. SOURCE: Committee on Living Well with Chronic Disease: Public Health Action to Reduce Disability and Improve Functioning and Quality of Life.

addressing chronic illness morbidity is to help each affected person and the population as a whole to live well, regardless of the illness in question or an individual’s own current state of disablement. The committee adopted the concept of living well, as proposed previously by other chronic disease experts (Lorig et al., 2006), to reflect the best achievable state of health that encompasses all dimensions of physical, mental, and social well-being. For each individual with chronic illness, to live well takes on a unique and equally important personal meaning, which is defined by a self-perceived level of comfort, function, and contentment with life. Living well is shaped by the physical, social, and cultural surroundings and by the effects of chronic illness not only on the affected individual but also on family members, friends, and caregivers. In this way, progress toward living well can be achieved through the combination of all efforts enacted across individual and societal levels to reduce disability and improve functioning and quality

of life, regardless of each unique individual’s current state of health or specific chronic illness diagnosis.

This concept of living well, integrated within a broader population health framework, is intended to promote a more holistic perspective beyond the traditional focus on other important goals, such as primary prevention or the prolongation of life expectancy alone. Moreover, it is intended also to heighten awareness that interventions and policies that promote function, reduce pain, remove obstacles for the disabled, or alleviate suffering at the end of life play an essential role in providing a more complete response for addressing chronic diseases in the United States today.

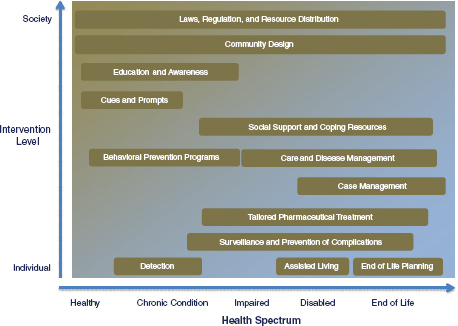

In this report the committee elected to use the “living well framework” to inform the consideration of policies and the allocation of resources to solve important issues related to chronic diseases in a manner that is tied to a more complete understanding of the interactions among individual, behavioral, social, and environmental characteristics. Specific strategies designed to help individuals live well must also be considered in the context of a broader array of activities targeting primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention for all persons, regardless of whether they already have a chronic illness (Figure 1-2).

Many strategies that are promoted for primary prevention, such as vaccination, tobacco cessation, physical activity promotion, healthful eating, and injury prevention, can also help persons who have already developed a chronic illness or disability to live more healthfully. In addition, strategies that prevent or delay complications, build coping skills, improve function, or alleviate pain and suffering may serve a dual purpose of reducing the magnitude of illness burden over an individual’s remaining years of life as well as reducing and/or delaying the development of additional complications or comorbidities in a way that serves to compress the period of morbidity until later in life (Hubert et al., 2002). Indeed, it is likely that the greatest societal benefit will emerge not from singular approaches, but from a deeper understanding of how different approaches might be coordinated to achieve the greatest progress toward living well for all persons with chronic illness.

Regardless of their scale or focus, most policies or programs to improve health require some form of investment that is both human and monetary. Moreover, even strategies that yield overall societal benefits may have adverse effects for some individuals or groups, including unforeseen and/or unintended consequences. All strategies should be fashioned with careful consideration of anticipated impacts, resource inputs, implementation steps, and plans for surveillance of both intended and unintended consequences.

FIGURE 1-2 Interaction of multilevel interventions and policies to achieve living well across the spectrum of health and chronic disease.

SOURCE: Adapted from Copyright Fielding, J.E., and S.M. Teutsch. 2011. An opportunity map for societal investment in health. Journal of the American Medical Association 305(20):2111. All rights reserved.

In this report, we attempt to highlight important considerations of a thoughtful population health approach for living well with chronic illness. Before introducing those concepts, however, it is important first to consider the evolution of American strategies designed to understand illness burden and how existing resources and strategies available to promote population health might help to guide the nature and scope of future living-well interventions.

A Brief History

The capacity of society to respond to health threats, chronic or otherwise, is influenced by the way in which it documents and interprets the magnitude and distribution of health outcomes. From its earliest colonial beginnings, Americans have paid particular attention to such life events as births, marriages, and burials as a part of religious or cultural traditions. At the outset, disease ranked with starvation as a primary threat to the

existence of many of the colonies. Infectious outbreaks, such as malaria, dysentery, typhoid, smallpox, and yellow fever, decimated many early colonial settlements (CDC and NCHS, [a]). Outbreaks of disease were met as emergencies with varied responses.

In the years just prior to the turn of the 19th century, large cities, such as Baltimore and Philadelphia, established boards of health as the forerunners of modern local health departments. Those boards attempted to introduce more systematic, population-based efforts to identify and track causes of serious health threats and to guide the public health response to epidemics. During the mid-19th century, states began enacting laws to expand and improve approaches to track causes of death. In 1879, the U.S. Congress created the National Board of Health, tasked to centralize information, engage in sanitary research, and collect vital statistics. Over time, the methods for documenting and interpreting the numbers and more precise causes of deaths in America continued to evolve, and this ultimately led to the establishment of the National Office of Vital Statistics of the Public Health Service in 1946 and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in 1963. Since that time, NCHS has produced reports of vital statistics and has worked with other agencies to advance methods to capture and analyze population health in America.

For the past half-century, efforts by organizations, such as the CDC (including NCHS), the World Health Organization (WHO), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and others, have used data from an evolving list of population health indicators to inform a variety of strategies by governmental public health entities, community-based nongovernmental organizations, and the health care system to address illness and promote health and function.

Recently, the increasing burden of chronic diseases globally has expanded the attention of these efforts to focus well beyond simply prolonging life, with an increasing emphasis on wellness and function. Implicit in this shift is a growing recognition that American society places less value on a longer life if additional years also bring additional pain and suffering or leave individuals without a capacity for independent decision making, the ability to perform activities of daily living independently, or enjoy relationships or financial security.

Today HHS, through CDC, AHRQ, NIH, and other centers, routinely tracks data and publishes reports on such outcomes as health behaviors; biological indicators of health; health care access, quality, utilization, disparities, and costs; prevalence of diseases; and vital statistics (BRFSS, [a]; CDC and NCHS, [a]; HCUPnet, [a]; MEPS, [a]). Beginning in the mid-1990s, the U.S. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) began working with epidemiologists and chronic disease program directors at the state and federal levels to select, prioritize, and define 73 chronic

disease indicators. These data are intended to summarize available information from surveys, registries, and other surveillance systems about the incidence, prevalence, events, and efforts to detect and treat select chronic diseases and their behavioral risk factors (CDC, [a]). The first set of indicators was published in 1999, with state-specific data published the following year. In 2001, the content of both reports became available online. In 2002, the CSTE adopted a revised and expanded set of indicators. Although this reflects progress in shining light on the magnitude of morbidity imposed by chronic illnesses, the current efforts do not encompass all chronic diseases and do not capture many of the meaningful negative effects on quality of life caused by different forms of functional impairment and disability.

Since 2004, NIH has funded the development of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to create, test, and recommend a more uniform set of tools for the measurement and surveillance of patient-reported health status indicators reflecting physical, mental, and social well-being (PROMIS, [a]). Although evidence-based and publicly accessible, PROMIS and similar tools have not yet been adopted more broadly for surveillance of quality of life or well-being for the U.S. population.

In parallel with PROMIS, other initiatives have tried to consider how population health indicators could be measured practically and used to inform local policies to address chronic disease (Parrish, 2010; Wold, 2008). Some examples of this work include the IOM’s State of the USA Health Indicators report (2008) and the University of Wisconsin’s Mobilizing Action Toward Community Health (MATCH) Project (Kindig et al., 2010). Although these initiatives are attempting to advance the capacity to understand the impact of chronic diseases and their risk factors on population health, practical considerations have led them to recommend only very brief metrics that are already being collected and are in the public domain. An example of one such metric is CDC’s HRQOL-4, which has been collected at the state level since 1993. Although readily available today, this metric lacks specific information about activity limitation, functional status, and experiential state. Over the coming decade, one key goal for the Healthy People 2020 initiative is to evaluate the use of PROMIS and other available metrics for monitoring health-related quality of life and well-being in the United States (Healthy People 2020, [a]). Indeed, as discussed throughout this report, without the implementation of a more robust system for population-level surveillance of indicators that reflect the full depth and distribution of chronic disease morbidity on different dimensions of quality of life and well-being, it will prove challenging to prioritize, evaluate, and refine strategies that aim to help all Americans to live well with chronic illness.

Summary Measures of the Burden of Chronic Illness

In addition to considering the societal burden of chronic disease in terms of specific dimensions of health status, well-being, social participation, or survivorship, methods are also available to quantify morbidity using summary measures that combine information on both mortality and nonfatal health outcomes into a single numerical index (Murray et al., 2002). Such measures are broadly intended to quantify not only mortality but also the impact of impairment or disability on population health when individuals are living with a particular illness. Typically, these summary measures express “either the expected number of future years of healthy life after a given age or the number of years that chronic disease and disability subtract from a healthy life” (Parrish, 2010).

One example of a population-health summary measure, developed by the WHO, expresses health states in terms of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), in which one less DALY is equal to the loss of one healthy life-year. The impact of a particular chronic health state on disability is often estimated from information collected from individuals in the population and then summed to reflect the burden of a particular disease on a group or population. In this context, the DALY burden or human toll associated with a given illness for a population becomes a function of the numbers of persons affected; the age at onset, the pattern of its natural history (i.e., duration, chronicity, and episodic nature); and its effects over time on disability, functioning, and premature mortality. Based on the DALY metric, Michaud and colleagues reported in 2006 that noncommunicable diseases cost the United States 33.1 million DALYs per year, based on data collected by WHO. Common chronic illnesses, including ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, major depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, HIV, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, and chronic neurological disorders together accounted for about 35 percent of this total, which corresponds to about 16 days of healthy life lost for every person in the U.S. population that year (Michaud et al., 2006).

Another common way to express the summative impact of chronic diseases for a population is through a cost of illness approach, which attempts to monetize the direct and indirect financial costs incurred by society for a particular chronic disease. The cost of illness method typically views direct costs as those associated with health care per se (e.g., clinic visits, hospitalizations, medications, medical devices, and therapy/rehabilitation services as well as public health initiatives focused on primary or secondary prevention). Conversely, indirect costs are those that are incurred through effects on premature mortality, reduced labor output (including consideration of public and private income assistance programs, which serve to replace labor

income for the disabled), and other consequences that lie beyond the health care system.

At the national level, direct health care spending in the United States can be assessed using the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEAs) (CMS, [a]). Currently, the NHEAs report health expenditures overall, by type of service delivered (e.g., hospital care, physician services), and by source of funding (e.g., private, Medicaid, Medicare), but not by categories of illness (Rosen and Cutler, 2009). The only exception is mental health and substance abuse treatment, which are reported separately by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2007). However, some estimates of the costs associated with major chronic diseases do exist from other sources.

For example, in a 2007 report, the Milken Institute examined treatment costs for seven common chronic diseases in the United States in 2003: cancers, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, stroke, mental disorders, and pulmonary conditions. This report estimated direct treatment expenditures to be $277 billion across those seven conditions, corresponding to 16 percent of total 2003 national health expenditures of $1.7 trillion (DeVol and Bedroussian, 2007; Smith et al., 2005). The authors further estimated that these seven conditions alone imposed indirect costs of $1.047 trillion on the U.S. economy in 2003 via reduced labor productivity (DeVol and Bedroussian, 2007). As concern has emerged about the fiscal burden of chronic diseases on the health care sector, the findings of this report underscore that this burden is indeed considerable. However, it is also striking that these estimates suggest the fiscal impact of chronic diseases on other sectors of the economy to be equal to or perhaps several-fold greater than their impact on direct medical spending alone.

Although such summary estimates are both striking and potentially more interpretable for decision makers and the public, there are notable limitations to the use of such measures for chronic disease morbidity. That said, the identification and wide-scale adoption of a common set of meaningful indicators that reflect the nonfatal burden of chronic diseases could prove instrumental in advancing efforts to enact, evaluate, and refine policies and other interventions to maximize progress toward living well. In this context, the discussion regarding how best to address the burden of chronic diseases might rise above a prioritized list based on different diagnoses, which tends to pit different diseases against one another for limited societal resources. The result of coordinated action that is focused instead on the common dimensions of living well might serve to align policies, programs, and the groups that advocate for them to achieve a more complete solution that advances quality of life and well-being for all of society. Subsequent chapters of this report discuss in more detail how metrics of living well can

be used to guide policies toward a more complete solution to address the burden of nonfatal chronic diseases in America today.

Inequalities in Living Well with Chronic Illness

Health inequalities are formed by cultural, historical, economical, and political structures in the United States (Lewis et al., 2011). Health and economic outcomes for individuals living with chronic illnesses vary by race and ethnicity. Understanding the distributions of health indicators at a population level assists in recognizing key health determinants and population groups. Reducing inequalities in health not only helps the individual but also improves the overall health of the population.

In 2010, racial and ethnic minorities made up 35.1 percent of the U.S. population. Hispanics contributed to the largest portion of minorities with 16 percent; second, African Americans at 12.2 percent; and, third, Asians at 4.5 percent (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). These rates are expected to grow. It is anticipated that by 2050 these groups will make up almost half of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004).

Compared with whites, African Americans are twice as likely to be diagnosed with diabetes (HHS, [a]). In 2009, arthritis and coronary heart disease affected African Americans slightly more than whites (CDC, 2010b). African Americans have a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension and stroke than all other race and ethnic groups. Compared with whites (the second-largest group living with both hypertension and stroke), 32.2 percent of African Americans have hypertension versus 23 percent of whites, and 3.8 percent experience stroke, compared with 2.5 percent of whites (CDC, 2010b).

American Indians/Alaskan Natives have lower rates of coronary heart disease but extremely high rates of diabetes in certain subgroups (CDC, 2010b; HHS, [b]). They also have higher chronic joint symptoms compared with whites (CDC, 2010b). Self-rated health status also differs by ethnic group. In 2003, approximately 7.4 percent of Asian Americans and 8.5 percent of white Americans consider themselves to be in fair or poor health, compared with 14.7 percent of African American, 16.3 percent of American Indians/Alaskan Natives, and 13.9 percent of Hispanic Americans (Cowling, 2006).

Serious psychological distress is reported at 30 percent more in African Americans than whites (HHS, [c]). Asian American women have the highest rate of suicide of all American women over 65 years old. Hispanic girls, grades 9–12, have 60 percent more suicide attempts than their white counterparts (HHS, [d]).

Research demonstrates drastic differences by socioeconomic status (SES) and, to a lesser extent, by race/ethnicity in health behaviors that

represent dominant risk factors for the development and progression of chronic diseases. In the United States, tobacco use is the most preventable cause of disease and disability (CDC, 2011). Over 8 million Americans have a disease or disability caused by smoking (Hyland et al., 2003). Smoking is related to a wide range of chronic diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and peptic ulcer disease (Fagerström, 2002). There is an increased prevalence of tobacco use among lower income individuals. Almost 30 percent of adults living below the poverty line smoke, compared with 18.3 percent of adults who are at or above the poverty line. In addition, tobacco use increases in populations with less education. Just over 25.1 percent of adults who do not have a high school diploma smoke, whereas 9.9 percent of college graduates smoke, compared with only 6.3 percent of adults with a graduate degree (CDC, 2011). American Indians/Alaskan Natives have the highest prevalence of smoking at 31.4 percent (CDC, 2011).

The distributions of obesity show a very different pattern, varying both by race/ethnicity, SES, and gender. Socioeconomic status, defined by educational levels and income, is linked to obesity (McLaren, 2007). In 2001, 31.1 percent of blacks and 23.7 percent of Hispanics were obese, compared with 19.6 percent of white Americans and 15.7 percent of others, including Asians. A similar range is shown by education, for which 15.7 percent of college graduates are obese compared with 27.4 percent of those who did not graduate from high school (IOM, 2006). Obesity is more prevalent in women with lower income. And 42 percent of women living at 130 percent of the poverty level or below are obese, compared with 29 percent living at or above the poverty level (CDC, 2010a).

Underlying population differences in social and environmental conditions affect racial and ethnic inequalities in distributions of chronic disease risk factors and morbidity, not genetic factors alone (IOM, 2006). Although health care plays a crucial role in the treatment of disease, disparities in health care are estimated to account for only a small fraction of premature mortality among racial and ethnic minorities. On average, disadvantaged ethnic minorities complete fewer years of formal education, have lower income, and are less likely to have health insurance. This leads to less access to beneficial health services and an overall lower quality of care received (IOM, 2003). Disadvantaged individuals have greater exposure to crowding and noise (Kawachi and Berkman, 2003), constrained conditions for exercise, and less access to well-stocked grocery stores (McGinnis et al., 2002). In contrast, social environments with more social capital and social cohesion are more available in advantaged communities (Cohen et al., 2003; Kawachi and Berkman, 2000). In this context, it is imperative that strategies to improve living well with chronic illness consider the potential impact on distributions of health outcomes across population subgroups,

as well as the way in which policies across other sectors, such as education, transportation, farming, and other areas, can indirectly impact health and contribute to disparities in health.

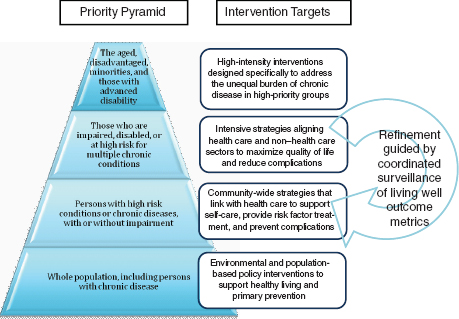

Frameworks to Guide Action Across Sectors

It can be daunting to consider how best to ensure a policy development process that promotes population health while considering the unequal distributions of chronic disease burden as well as the potential ripple effects when policies from different sectors collide. In this context, the committee thought it helpful to introduce another concept, which depicts a pyramid of layered intervention strategies to achieve living well (Figure 1-3). This pyramid attempts to frame different potential intervention strategies not only in terms of their target level (i.e., population-wide versus individually based) but also in terms of their relative intensity to meet the needs of those who shoulder the greatest burden of nonfatal chronic illnesses. This framework is used in subsequent chapters to communicate the nature and

FIGURE 1-3 Prioritization scheme for policies and other interventions to address the burden of nonfatal chronic diseases across the population.

SOURCE: Committee on Living Well with Chronic Disease: Public Health Action to Reduce Disability and Improve Functioning and Quality of Life.

scope of different policy and other intervention recommendations made by the committee.

At the base of the priority pyramid are broad societal strategies to promote health and prevent disease for the entire population. At the very broadest level is the Health in All Policies (HIAP) perspective. This perspective acknowledges that health is fundamental to every sector of the economy and that every policy, large and small, whether focused primarily on transportation, education, agriculture, energy, trade, or another area, should take into consideration its impact on health (Aspen Institute, [a]; Blumenthal, 2009). Clearly, achieving such a goal is no trivial pursuit and is likely to require top-down coordination of policy sectors at the national, state, and local levels (The Strategic Growth Council, [a]) as well as a shared sense of participation and accountability among individuals, groups, institutions, businesses, communities, and governments to preserve, protect, and advance population health at every level. WHO and numerous other entities worldwide have promoted the development of frameworks and strategies to advance the HIAP perspective (WHO, [a]). From an operational perspective, the implementation of such a high-level and coordinated focus on health is likely to take considerable time to mature and will clearly require fundamental changes in policy development processes across both governmental and private sectors.

With slightly more focus, the acceleration of public and health system policies specifically intended for promoting health through the support of healthier lifestyle behaviors and access to evidence-based preventive services is also urgently needed. Although dedicated health policies are also typically directed at a population level, it is important to recognize that they can have meaningful (and often greater) benefits for individuals already affected by a chronic illness or high-risk condition (e.g., high cholesterol, prediabetes). Moreover, the presence of policies that enhance support and accessibility can amplify the impact of other environmental, social, and health care resources to help chronically ill persons live more healthful and higher quality lives. In this context, policy interventions serve as the very foundation of the priority pyramid and are discussed in greater depth in Chapter 3.

Moving up the priority pyramid, it is important to recognize that individuals who have already been diagnosed with a chronic illness can also benefit from access to additional care management and support resources in both health care and non–health care sectors. Such resources may include more intensive risk factor surveillance, medication therapies, medical procedures, educational and behavioral programs, and other support systems. The intensity of these resources needs increases among individuals who have MCCs and those who have progressed to develop impairment or disability. Exposure to multiple care providers and use of care management

resources in multiple settings, though often needed, may introduce new problems if poorly aligned or fragmented. Poor coordination of services for the chronically ill can lead to care that, although intensive, is both ineffective and wasteful. Moreover, such care can also increase the possibility of harm caused by conflicting therapies or poor communication among affected individuals and providers (IOM, 1999).

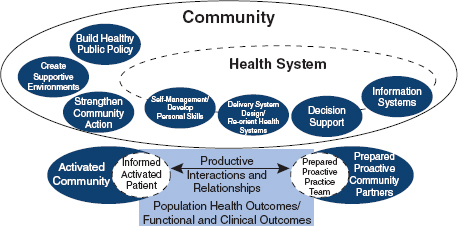

Because many treatment and self-care resources for persons with nonfatal chronic illnesses can be complementary, they are likely to offer the greatest benefit for an individual and for the population if they are coordinated across sectors in ways that reach more individuals, reinforce behaviors throughout communities, provide the most efficient use of limited resources, and avoid harms. For several years, professionals in both the health care and the public health sector have worked to develop and evaluate frameworks for the coordination of resources to prevent and manage chronic diseases. The Chronic Care Model (CCM), for example, is a conceptual framework designed to identify structural elements in the health system that are believed to impact chronic disease outcomes through their ability to create productive interactions among informed, activated patients and prepared, productive care providers. Increasingly, the CCM is being used as a foundation for efforts to define the model elements of a patient-centered medical home (NCQA, [a]) and to guide broader concepts related to transformation of health systems into “accountable care” organizations. In this context, the CCM is an important consideration in the discussion of how best to implement strategies that will transform the structure and process of health care delivery.

Although used initially as a tool to improve chronic health care services, the CCM does attempt to overlay health care delivery on a broader landscape of community resources and policies. Since its initial introduction in the 1990s, several groups have attempted to refine the CCM to place even stronger emphasis on community influence and prevention (Barr et al., 2003). One such adaption, the Expanded Chronic Care Model (Barr et al., 2003), depicted in Figure 1-4, advances the perspective that care model elements bridge across health care and non–health care sectors and that an overarching goal of those bridging support structures and programs is to improve population health outcomes not only by impacting the health and behaviors of individual patients and their health care providers but also by activating communities and preparing community partners.

Although integration frameworks, such as the Expanded Chronic Care Model, may prove helpful in coordinating care resources for persons with nonfatal chronic illnesses, much more work is needed not only to understand the best approaches for developing clinical-community linkages (Ackermann, 2010; Etz et al., 2008) but also to guide higher level strategies that ensure an efficient interface across policy sectors and among public and

FIGURE 1-4 The Expanded Chronic Care Model.

SOURCE: Barr, V., S. Robinson, B. Marin-Link, L. Underhill, A. Dotts, D. Ravensdale, and S. Salivaras. 2003. The expanded chronic care model: An integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Healthcare Quarterly 7(1):73–82.

private partners to advance population health and living well with chronic illness on a much larger scale. It is the position of the committee that such progress will require not only new structures and processes for collaborative policy development but also the careful alignment of incentives to promote accountability toward population health and greater coordination of efforts to achieve that goal. A more robust description of interventions in communities and strategies for coordinating interventions across non–health care and health care settings appears in Chapters 4 and 6.

The burden of chronic disease in America today is indeed vast and continues to grow. The sheer magnitude of this burden for society; the striking inequalities in living well among minorities, the elderly, and the disadvantaged; and the simple fact that numerous chronic diseases are leading causes of death and disability are all emblematic of the considerable limitations of existing policies, programs, and systems of care and support for Americans living with chronic illness today.

New strategies for understanding and addressing this burden must give ample consideration to all chronic illnesses and all dimensions of suffering. Indeed, all chronic diseases have the potential to reduce population health not only by causing premature death but also by limiting people’s capacity

to live well during the remaining years of their lives. For society, living well is impacted not only by the numbers of persons who suffer from chronic illnesses but also by the effects of those illnesses on their quality of life and that of their peers, caregivers, children, and dependents. In this context, the overall burden of chronic diseases could be drastically reduced through coordinated efforts toward both primary prevention and other interventions and policies that are designed to improve health for persons already living with chronic illness. Although both of these overarching goals are essential to the health of America, the remainder of this report focuses on the goal of living well with chronic illness.

In the chapters that follow, the committee consistently adopts a population health perspective to guide discussions of how individuals’ genes, biology, and behaviors interact with the social, cultural, and physical environment around them to influence health outcomes for the entire population. Subsequent chapters consider and recommend practical steps toward advancing efforts to coordinate action across sectors to help society live well with all forms of chronic illness and to address gaping inequalities in their distribution and their complications among vulnerable population subgroups. Because different chronic illnesses impact social participation and quality of life in varied ways, the committee also uses examples of different chronic diseases to illustrate key concepts. This, however, should not be viewed as an assertion that some diseases are more burdensome or more important than others. In the end, it is our hope that this report will guide immediate and precise action to reduce the burden of all forms of chronic disease through the development of cross-cutting and coordinated strategies that can help all Americans to live well.

Ackermann, R.T. 2010. Description of an integrated framework for building linkages among primary care clinics and community organizations for the prevention of type 2 diabetes: Emerging themes from the CC-Link study. Chronic Illness 6(2):89–100.

Anderson, G. 2010. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. http://www.rwjf.org/files/research/50968chronic.care.chartbook.pdf (accessed December 2, 2010).

Aspen Institute (a). Health in All Policies. http://www.aspeninstitute.org/policy-work/health-biomedical-science-society/health-stewardship-project/principles/health-all (accessed October 19, 2011).

Barr, V.J., S. Robinson, B. Marin-Link, L. Underhill, A. Dotts, D. Ravensdale, and S. Salivaras. 2003. The expanded Chronic Care Model: An integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Hospital Quarterly 7(1):73–82.

Blumenthal, S. 2009. Health in all policies. Huffington Post, July 31. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/susan-blumenthal/health-in-all-policies_b_249003.html (accessed October 4, 2011).

BRFSS (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) (a). http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/ (accessed October 14, 2011).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (a). Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm (accessed October 4, 2011).

CDC. 2010a. Obesity and Socioeconomic Status in Adults: United States, 2005–2008. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db50.htm#ref3 (accessed December 19, 2011).

CDC. 2010b. Summary Health Statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC. 2011. Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 2005–2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(35):1207–1212.

CDC and NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics) (a). U.S. Vital Statistics System. Major Activities and Developments, 1950-95. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/usvss.pdf (accessed October 4, 2011).

Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation. 2010. Issue Brief January 2010. The Cost Burden of Disease. U.S. and Michigan. http://www.chrt.org/assets/price-of-care/CHRT-Issue-Brief-January-2010.pdf (accessed October 4, 2011).

CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) (a). National Health Expenditure Data. Overview. https://www.cms.gov/nationalhealthexpenddata/ (accessed October 4, 2011).

Cohen, D.A., T.A. Farley, and K. Mason. 2003. Why is poverty unhealthy? Social and physical mediators. Social Science and Medicine 57:1631–1641.

Cowling, L.L. 2006. Chapter 17. Health and dietary issues affecting African Americans. In California Food Guide: Fulfilling the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Care Services and California Department of Public Health. http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/dataandstats/reports/Documents/CaliforniaFoodGuide/17HealthandDietaryIssuesAffectingAfricanAmericans.pdf (accessed October 18, 2011).

DeVol, R., and A. Bedroussian. 2007. An Unhealthy America: The Economic Burden of Chronic Disease: Charting a New Course to Save Lives and Increase Productivity and Economic Growth. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Institute.

Etz, R.S., D.J. Cohen, S.H. Woolf, J.S. Holtrop, K.E. Donahue, N.F. Isaacson, K.C Stange, R.L. Ferrer, and A.L. Olson. 2008. Bridging primary care practices and communities to promote healthy behaviors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35(Suppl 5):S390–S397.

Fagerström, K. 2002. The epidemiology of smoking: Health consequences and benefits of cessation. Drugs 62(Suppl 2):1–9.

HCUPnet (a). Welcome to HCUPnet. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/ (accessed October 14, 2011). Healthy People 2020 (a). Health-Related Quality of Life and Well-Being. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/QoLWBabout.aspx (accessed October 4, 2011).

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) (a). African American Profile. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=51 (accessed December 19, 2011).

HHS (b). Diabetes and American Indians/Alaska Natives. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?ID=3024 (accessed October 18, 2011).

HHS (c). Mental Health and African Americans. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?ID=6474 (accessed January 5, 2012).

HHS (d). Mental Health Data/Statistics. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=9 (accessed January 5, 2012).

HHS. 1996. Surgeon General Report Physical Activity and Health. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/ListByDate.html (accessed October 13, 2011).

HHS. 2010. Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Strategic Framework Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions. http://www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/mcc/mcc_framework.pdf (accessed October 4, 2011).

Hubert, H.B., D.A. Bloch, J.W. Oehlert, and J.F. Fries. 2002. Lifestyle habits and compression of morbidity. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 57(6):M347–M351.

Hyland, A., C. Vena, J. Bauer, Q. Li, G.A. Giovino, J. Yang, K.M. Cummings, P. Mowery, J.

Fellows, T. Pechacek, and L. Pederson. 2003. Cigarette smoking-attributable morbidity—United States, 2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 52(35):842–844.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1999. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2006. Examining the Health Disparities Research Plan of the National Institutes of Health: Unfinished Business. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008. State of the USA Health Indicators: Letter Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2010. Distribution of U.S. Population by Race/Ethnicity, 2010 and 2050. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation. http://facts.kff.org/chart.aspx?ch=364 (accessed December 19, 2011).

Kawachi, I., and L.F. Berkman. 2000. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In Social Epidemiology, edited by I. Kawachi and L.F. Berkman. New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 174–190.

Kawachi, I., and L.F. Berkman. 2003. Neighborhoods and Health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kindig, D. 2007. Understanding population health terminology. Milbank Quarterly 85(1): 139–161.

Kindig, D.A., B.C. Booske, and P.L. Remington. 2010. Mobilizing Action Toward Community Health (MATCH): Metrics, incentives, and partnerships for population health. Preventing Chronic Disease 7(4):A68. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jul/10_0019.htm (accessed November 16, 2011).

Kulkarni, S.C., A. Levin-Rector, M. Ezzati, and C.J. Murray. 2011. Falling behind: Life expectancy in U.S. counties from 2000 to 2007 in an international context. Population Health Metrics 9(16). http://www.pophealthmetrics.com/content/9/1/16 (accessed November 16, 2011).

Lewis, J.M., M. DiGiacomo, D.C. Currow, and P.M. Davidson. 2011. Dying in the margins: Understanding palliative care and socioeconomic deprivation in the developed world. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 42(1):105–118.

Lorig, K., H.R. Holman, D. Sobel, D. Laurent, V. González, and M. Minor. 2006. Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions. 3rd ed. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing.

McGinnis, J.M., and W.H. Foege. 1993. Actual causes of death in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association 270(18):2207–2212.

McGinnis, J.M., P. Williams-Russo, and J.R. Knickman. 2002. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Affairs (Millwood) 21(2):78–93.

McLaren, L. 2007. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiological Reviews 29(1):29–48. MEPS (Medical Expenditure Panel Survey) (a). http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/ (accessed October 14, 2011).

Michaud, C.M., M.T. McKenna, S. Begg, N. Tomijima, M. Majmudar, M.T. Bulzacchelli, S. Ebrahim, M. Ezzati, J.A. Salomon, J.G. Kreiser, M. Hogan, and C.J. Murray. 2006. The burden of disease and injury in the United States 1996. Population Health Metrics 4(11). http://www.pophealthmetrics.com/content/4/1/11 (accessed November 16, 2011).

Miller, T.R., and D.T. Levy. 2000. Cost-outcome analysis in injury prevention and control: Eighty-four recent estimates for the United States. Medical Care 38(6):562–582.

Mokdad, A.H., J.S. Marks, D.F. Stroup, and J.L. Gerberding. 2004. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Journal of the American Medical Association 291(10):1238–1245.

Murray, C.J., J.A. Salomon, C.D. Mathers, and A.D. Lopez. 2002. Summary Measures of Population Health: Concepts, Ethics, Measurement and Applications. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2002/9241545518.pdf (accessed October 14, 2011).

Nagi, S. 1965. Some conceptual issues in disability and rehabilitation. In Sociology and Rehabilitation, edited by M.B. Sussman. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. NCCDPHP (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion) (a). Chronic Diseases and Health Promotion. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm (accessed October 13, 2011).

NCCDPHP. 2009. Chronic Diseases. The Power to Prevent, The Call to Control. At a Glance 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/AAG/pdf/chronic.pdf (accessed October 4, 2011).

NCQA (National Committee for Quality Assurance) (a). NCQA Patient-Centered Medical Home. http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/PCMH%20brochure-web.pdf (accessed August 10, 2011).

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2011. PROMIS Instruments Available for Use. http://www.nihpromis.org/Documents/Item_Bank_Tables_Feb_2011.pdf (accessed October 4, 2011).

Parrish, R.G. 2010. Measuring population health outcomes. Preventing Chronic Disease 7(4):A71. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jul/10_0005.htm (accessed November 16, 2011).

PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) (a). http://www.nihpromis.org/ (accessed October 14, 2011).

Rosen, A.B., and D.M. Cutler. 2009. Challenges in building disease-based national health accounts. Medical Care 47(7 Suppl 1):S7–S13.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2007. National Expenditures for Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993–2003. http://www.samhsa.gov/spendingestimates/samhsafinal9303.pdf (accessed October 4, 2011).

Smith, C., C. Cowan, A. Sensenig, A. Catlin, and the Health Accounts Team. 2005. Health spending growth slows in 2003. Health Affairs 24(1):185–194.

The Strategic Growth Council (a). Health in All Policies Task Force—About Us. http://sgc.ca.gov/hiap/about.html (accessed October 4, 2011).

Tengs, T.O., M.E. Adams, J.S. Pliskin, D.G. Safran, J.E. Siegel, M.C. Weinstein, and J.D. Graham. 1995. Five-hundred life-saving interventions and their cost-effectiveness. Risk Analysis 15(3):369–390.

Thorpe, K.E. 2006. Factors accounting for the rise in health-care spending in the United States: The role of rising disease prevalence and treatment intensity. Public Health 120(11):1002–1007.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2004. U.S. Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 2000–2050. http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/ (accessed January 5, 2012).

WHO (World Health Organization) (a). HEALTH21: An Introduction to the Health for All Policy Framework for the WHO European Region. European Health for All Series No. 5. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/88590/EHFA5-E.pdf (accessed October 4, 2011).

WHO. 1986. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion. Ottawa, 21 November 1986—WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1. http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf (accessed October 4, 2011).

WHO. 2004. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html (accessed October 4, 2011).

WHO. 2009. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/global_health_risks/en/index.html (accessed October 4, 2011).

Wold, C. 2008. Health Indicators: A Review of Reports Currently in Use. Pasadena, CA: Wold and Associates. http://www.cherylwold.com/images/Wold_Indicators_July08.pdf (accessed November 16, 2011).