Chronic Illnesses and

the People Who Live with Them

Some chronic diseases are well known as “causes” of mortality. Cardiovascular disease, many cancers, stroke, and chronic lung disease are the most common causes of death in the United States (Mokdad et al., 2004; Thacker et al., 2006). There are many other chronic illnesses, however, that may or may not directly cause death but may have multiple effects on quality of life. The quality of life impact of these chronic illnesses is not as widely appreciated in public health, clinical practice, or health policy planning. Chronic illnesses often cause bothersome health problems for those affected and/or those around them, problems that persist over time. These include problems with physical health (e.g., distressing symptoms, physical functional impairment), mental health (e.g., emotional distress, depression, anxiety), or social health (e.g., social functional impairment), all of which are associated with lower quality of life (Cella et al., 2010). In many people with chronic illnesses, a mild impairment in any single one of these aspects of health leads to impairments in other aspects and may progress further to disability.

There is, in fact, a spectrum of chronic diseases that are in some ways quite disparate, yet they share certain commonalities that merit their being listed together. They are disparate in that they affect different organ systems and are frequently characterized by different time courses and the severity of disease burden. They are similar in that their effects on health and individual functioning share common pathways and outcomes. This chapter explores the differences and similarities among many chronic diseases,

considers several exemplar diseases, health conditions, and impairments in more detail, and examines the people living with these illnesses and the ways in which they are affected.1

In this section, we first consider the nature of chronic diseases, including their similarities and differences. We then discuss the effects of these illnesses on the ability to live well with them.

The National Center for Health Statistics has defined chronic diseases as those that persist for 3 months or longer or belong to a group of conditions that are considered chronic (e.g., diabetes), regardless of when they began. Although some (e.g., polymyalgia rheumatica, depression) may resolve, most are lifelong diseases. Chronic diseases can vary in multiple ways, including their stage at presentation and characteristic clinical symptoms and their natural history (time course). Some specific conditions have typical time courses for clinical progression. Other chronic diseases, such as treated breast or prostate cancers, may follow a quiescent pattern for many years. Similarly, the health burden in terms of symptoms and functional impairment, requirements for self-management, effects on significant others, and individual economic impact vary. This results in disparate patterns of human suffering across the spectrum of chronic illnesses. Table 2-1 displays selected patterns of chronic illnesses along important dimensions. For example, some illnesses (e.g., diabetes) have high self-management requirements, whereas others (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) may require substantial care from others. Age of onset may also influence complications and burden; for example, older onset rheumatoid arthritis is associated with more shoulder involvement and symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica and less frequent hand deformities compared with younger onset disease (Turkcapar et al., 2006). The stability of the condition over time is also an important determinant of overall health burden.

Below we summarize the spectrum of chronic diseases as early, moderate, and late stage. As highlighted in Table 2-1, individuals with certain chronic illnesses, such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes mellitus, may

![]()

1Some chronic illnesses have a recognized precursor state (e.g., osteopenia, hyperlipidemia, ductal carcinoma in situ) that may or may not progress to a chronic condition that people sense and suffer from. Although these presymptomatic states, if diagnosed, may cause symptoms (e.g., worry) or socioeconomic consequences (e.g., inability to obtain insurance), this report focuses on persons who actually have and are living with a chronic illness, not just a precursor state. Thus, such states as asymptomatic hypothyroidism or stage 3 chronic kidney disease are not considered.

present at various stages during the course of their illness with different health and economic consequences.

Chronic illnesses can be characterized by the stage (i.e., clinical severity), pattern (i.e., continuous versus intermittent symptoms), and anticipated course (i.e., stable, fixed deficit versus progressive). Because the stage of the condition has the largest impact on health and social consequences, we have organized this section around condition stages.

Early-Stage Chronic Illnesses

We define early-stage chronic illnesses as ones that cause little or no functional impairment and impose a low burden on others. This often characterizes certain chronic illnesses early after their diagnosis or in their uncomplicated stages. For example, such illnesses as benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) or early Parkinson’s disease have mild symptoms and burden. Some chronic early-stage illnesses, such as uncomplicated diabetes or New York Heart Association stage I (i.e., individuals with heart disease with no physical limitations) or II heart failure (i.e., individuals with heart disease with slight physical activity limitations), although associated with low functional impairment and burden to others, are associated with a high self-management burden (e.g., the need to monitor sodium and fluid intake and daily weight in heart failure, the need for self-monitoring of blood glucose in diabetes). Other early-stage chronic illnesses, such as mild asthma or osteoarthritis, may cause physical symptoms and functional limitation only intermittently, with asymptomatic periods in between, requiring a low to moderate degree of self-management.

Moderate-Stage Chronic Illnesses

Moderate-stage illnesses can be characterized by moderate, as opposed to low, degree of functional impairment and disability and moderate to high self-management and caregiver burden. At this stage, symptoms often interfere with usual lifestyles. Examples include painful hip or knee osteoarthritis and stage 2 or 3 Parkinson’s disease.

Several illnesses are associated with disabling episodic flares, although they may have low burden between flares. They are distinguished from early-stage illnesses following this pattern in that they cause moderate to severe, episodic disability (e.g., hospitalization for a flare of COPD), increased self-management and caregiver burden, and moderate to high economic impact. COPD, rheumatoid arthritis, depression, and migraine headache are conditions that often follow this pattern. Some people with complicated diabetes may have functional impairment due to peripheral neuropathy or a lower extremity amputation yet remain stable for some years, despite high

TABLE 2-1 Selected Patterns of Chronic Illnesses: Stage, Chronicity, Burden, and Example Illnesses

| Health Burden and Consequences (not including economic) | ||||||

| Stage | Chronicity/ Time Course |

Symptomsa | Functional impairment/ disability |

Self-management burden |

Burden to others | Example Illnesses |

| Early | Chronic with episodic flares |

Minimal or none between flares |

Low | Variable | Low | Asthma in adults, mild degenerative joint disease |

| Chronic | Mild | Low | Low | Low | BPH, mild Parkinson's disease | |

| Chronic | Mild | Low | High | Low | Uncomplicated but symptomatic diabetes, NYHA 1 or II heart failure |

|

| Moderate | Chronic with episodic flares |

Mild or minimal between flares, moderate or severe during flares |

Moderate | Moderate | Modcrat | COPD, RA, depression, migraine headache |

| Chronic, quiescent |

None to moderate |

Low | Low | Low | Breast or prostate cancer in remission |

|

| Chronic, stable | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate | Complicated diabetes, mild to moderate stroke, mild to moderate posttraumatic states, RA with some joint deformities |

|

| Chronic, pcogreiiive |

Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High | Severe ostcoarthritis, server Parkinson's disease. progressive Alzheimer's disease, progressive macular degeneration, progressive hearing impairment |

|

| Late | Chronic, pepgreiiive |

Moderate or server |

High | Variable | High | Severe dementia, severe diabetes with eitensiie vascular disease |

| Chronic, slowly progresive |

Moderate or server |

High | High | High | NYHA Class III or IV heart failure, COPD with chronic respiratory failure, end-stage renal disease en dialysis |

|

| Terminal | Severe | High | High | High | Metastatic cancer; patients in hospice |

NOTE: BPH = benign prostatic hyperplasia; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NYHA = New York Heart Association; RA = rheumatoid arthritis.

aSpecific symptoms vary by condition

self-management burden, moderate caregiver burden, and moderate to high economic impact on the individual. Similarly, people with a posttraumatic disabling condition or previous mild to moderate stroke may have a chronic pattern that remains stable over some time despite having moderate functional impairment and disability and moderate to high self-management and caregiver burden and individual economic impact.

Another pattern shown by moderate-stage chronic illnesses is more progressive. Alzheimer’s disease typically begins with memory loss and is later associated with functional impairment and behavioral and psychological complications, leading to moderate to high self-management and caregiver burden and individual economic impact. People with Parkinson’s disease and some with macular degeneration or hearing impairment may also experience this time course and burden. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) often begins with milder symptoms and burden but may progress rapidly to severe disability and death.

Late-Stage Chronic Illnesses

We define late-stage chronic illnesses as those that are slowly or rapidly progressive or terminal and are characterized by high functional impairment and disability and self or caregiver management burden. People with late-stage chronic illnesses often have multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) and may suffer a rapidly progressive decline in multiple functions. For example, people with severe dementia or people with diabetes and severe vascular disease often have a progressive course with high burden on significant others. In its terminal stage, metastatic cancer is often accompanied by a rapidly progressive, downhill course. In contrast, some people with late-stage chronic illnesses progress more slowly. For example, some people with end-stage renal disease who are on dialysis or some people with severe COPD and require chronic oxygen may remain stable for years. Other chronic conditions (e.g., those with spinal cord injuries) may result in high functional impairment and remain stable for many years.

Variation in a Chronic Illness in Time Course,

Health Burden, and Consequences

Although Table 2-1 indicates differences in commonly encountered patterns among chronic illnesses, it also highlights the marked variation within them. A single chronic illness may, in different people, demonstrate its own range of time course and burden. Some people with the same condition may progress from mild burden to severe limitation to disability or death at a constant, rapid rate, and others may progress slowly or not at all. For example, although the median survival for a person younger than

age 75 with Alzheimer’s disease is 7.5 years, a quarter do not survive 4.2 years and another quarter live beyond 10.9 years (Larson et al., 2004). Similarly, some people with diabetes progress inexorably to severe visual impairment, and others show little evidence of severe ocular complications or retinopathy regression even years after diagnosis (Klein et al., 1989). Only a few illnesses have a “typical” type of progression in that the vast majority of affected people show the same rate of worsening status. Most chronic illnesses are more variable, with different individuals with the same illness progressing at widely varying rates. The variation in progression rates is often independent of medical treatment. As a result of the variability of the natural history of individual illnesses, comorbidity, interactions between illness and environment, and adverse effects of treatments, the true burden of chronic illness in an individual is inconsistent and sometimes unpredictable. Thus, typical illness patterns of consequences are only rough guides. Any individual person may have a health burden that varies from the typical situation.

THE SPECTRUM OF CHRONIC ILLNESSES:

COMMON CONSEQUENCES

In addition to demonstrating differences among chronic illnesses, Table 2-1 also displays their common consequences. It is useful to consider that all of these illnesses create a common human burden of suffering. Although these illnesses have multiple mechanisms leading to suffering with variable time courses and severity, they all affect the same aspects of health: physical, mental, and social (Cella et al., 2010). A variety of models have been used to describe the process leading from disease to consequences in these aspects, including the Disablement Model that includes pathology; impairment at the tissue, organ, or body level, functional limitations; and disability (Nagi, 1976). More recently, the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (known as ICF) has classified health and health-related domains from “body, individual and societal perspectives by means of two lists: a list of body functions and structure, and a list of domains of activity and participation. Since an individual’s functioning and disability occurs in a context, the ICF also includes a list of environmental factors” (WHO, [a]). Regardless of the model used to explain the pathway from disease to consequences, chronic illnesses all lead, in their own ways, to human suffering (Cassell, 1983). In Table 2-1, we have rated the health burden and consequences of chronic illnesses along four dimensions: functional impairment/disability, self-management burden, and burden to others. The economic impact of chronic illness to the individual is described separately later in the chapter.

Below we discuss important dimensions of the health burden of chronic

illnesses and mention a measurement approach developed by the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). The PROMIS instruments also measure related constructs of social support, interpersonal attributes, and global health but do not include management burden directly or caregiver burden (Cella et al., 2010). In a pilot study of a large but unrepresentative sample of the general population, PROMIS selected five domains to assess health-related quality of life in people with chronic illnesses: physical function, fatigue, pain, emotional distress, and social function (Rothrock et al., 2010). They found that people with chronic illnesses reported poorer scores on these domains than did people without such illnesses and that people with two or more chronic illnesses had poorer scores than people with only one had.

Symptoms

These are medical or psychiatric symptoms that can be measured quantitatively and/or qualitatively. Examples include pain, fatigue, immobility, dyspnea on exertion, claudication (lameness), foot dysesthesia (numbness), depressive symptoms, seizures, and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The PROMIS approach measures physical symptoms, emotional distress, cognitive function, and positive psychological function (Cella et al., 2010).

Functional Impairment/Disability

Functional impairment can relate to restrictions in physical, mental, or social function. Disability is a more severe impairment that limits the performance of functional tasks and fulfillment of socially defined roles (handicap). For example, physical disability is the inability to complete specific physical functional tasks, called activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), that are important to daily life. The PROMIS measures assess both physical function and social function.

Chronic illnesses can cause functional impairment or disability through any of the three following health pathways:

1. Directly causing impairment or disability

2. Causing other medical complications that lead to impairment and disability

3. Causing mental health complications that lead to impairment and disability

Below we consider examples of each.

![]()

FIGURE 2-1 Osteoarthritis.

Chronic Illnesses Directly Causing Disability

Osteoarthritis causes impairment or disability directly through reduced mortality or pain in such joints as the knee or hip. Knee osteoarthritis results in 25 percent of affected individuals having difficulty performing activities of daily living due to pain and limited mobility (CDC, [c]). Knee and hip osteoarthritis are the third leading cause of years lived with disability in the United States (Figure 2-1) (Michaud et al., 2006).

Chronic Illnesses Leading to Other Medical Conditions

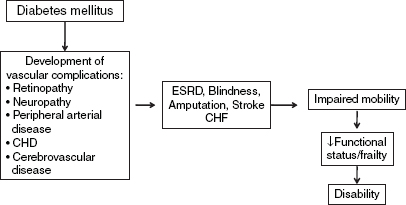

Diabetes can lead to impairment and disability indirectly, such as its effects on blood vessels. For example, visual impairment and end-stage renal disease are often microvascular complications, and coronary heart and cerebrovascular disease are frequently macrovascular complications (Figure 2-2).

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey show that cardiovascular disease (i.e., coronary heart disease or chronic

FIGURE 2-2 Diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease as examples of complications leading to disability.

NOTE: CHD = chronic heart disease; CHF = chronic heart failure; ESRD = end stage renal disease.

heart disease [CHD], heart failure, and stroke) and obesity among older adults with diabetes were associated with greater disability in several areas, including lower extremity mobility, general physical activity, activities of daily living, and instrumental activities of daily living (Kalyani et al., 2010). Data from the Women’s Health and Aging Study show that women with diabetes had a higher prevalence of mobility disability and severe walking limitation and that this was partially explained by peripheral arterial disease and peripheral nerve dysfunction (Volpato et al., 2002).

Chronic Illnesses Leading to Mental Health Conditions

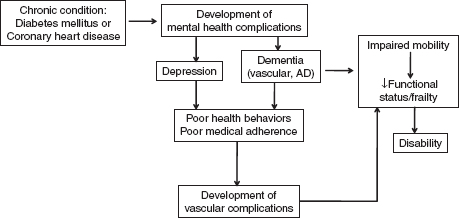

Chronic medical illnesses, such as diabetes, may also lead to mental health illnesses, such as depression and dementia, which have an adverse effect on health behaviors, leading to increased risk of clinical complications (Figure 2-3).

Both diabetes and cardiovascular disease are associated with an increased risk of developing depression (Mezuk et al., 2008; Rugulies, 2002). Conversely, depressive disorders in persons with diabetes are also associated with poor adherence to therapy (Gonzalez et al., 2008), worse control of glycemia and cardiovascular risk factors (Lustman et al., 2000), and greater diabetes complications (De Groot et al., 2001). Thus, individuals who develop depression are at higher risk of disability secondary to their greater propensity to develop vascular complications. Similarly, population-based studies indicate that type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for age-related cognitive decline (Biessels et al., 2008) with a 1.5- to 2.0-fold increased

FIGURE 2-3 Association of chronic illnesses with mental health consequences. NOTE: AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

risk of all-cause dementia (Cukierman et al., 2005). Studies also show that cognitive impairment is associated with poor diabetes self-management behaviors (Sinclair et al., 2000; Thabit et al., 2009) hyperglycemia (Munshi et al., 2006), and higher prevalence of diabetes complications (Roberts et al., 2008), which are predicted to contribute to functional, in addition to cognitive, impairment in this population.

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion released a public health action plan on mental health promotion and chronic disease prevention, which contains eight strategies to integrate mental health and public health programs that address chronic disease (CDC, 2011c). The eight strategy categories include surveillance, epidemiology research, prevention research, communication, education of health professionals, program integration, policy integration, and systems to promote integration. In recognizing the complexity of living well and effectively managing a chronic illness when a serious mental health condition is present, the committee has included a separate article highlighting depression care in patients with medical chronic illness (see Appendix A).

Chronic Illness Management Burden

In many cases, patients themselves must deliver their own care to effectively manage the chronic illnesses they live with, demanding consistent participation from patients and caregivers (Bayliss et al., 2003). In doing so, patients put forth substantial time, effort, and inconvenience that accompany day-to-day management of the illness. To properly manage their condition, patients typically run through the process of joining in physically and psychologically beneficial activities, working with health professionals to ensure adherence to treatment guidelines, monitoring health and making appropriate care decisions, and managing the effects of the illness on their physical, psychological, and social well-being (Bayliss et al., 2003). Any disruption to this process can have negative consequences on an individual’s health and livelihood (Bayliss et al., 2003).

To effectively address the multiple determinants behind almost all chronic illnesses, self-management regimens dictate appropriate medical guidelines as well as psychological and social functioning (Newman et al., 2004). Chronic illnesses factor into patient lifestyle choices, such as diet, level of physical activity, and suitable living environments, forcing self-management regimens for those illnesses to cross over multiple domains and affect the quality of a patient’s life (Newman et al., 2004). Patients with diabetes, for example, maintain day-to-day self-management routines typically including multiple components (e.g., self-monitoring of blood glucose, carbohydrate counting/awareness, home dialysis, home oxygen use, and

daily weights and check-ins with disease management programs). With all these activities, diabetes patients understandably perceive management of their condition as burdensome, frustrating, and overwhelming, which can have further negative consequences on their health (Weijman et al., 2005).

As Weijman et al. (2005) found, adherence to self-management activities has strong ties to the perceived burden. Patients who do not see these activities as burdensome perform them more frequently with close regard to proposed guidelines and reported better health outcomes in relation to their diabetes (Weijman et al., 2005). In contrast, patients who saw these activities as burdensome reported poorer health outcomes in relation to their diabetes, higher rates of depression and fatigue, and overall poorer quality of life (Weijman et al., 2005). Despite consistent evidence in support of self-management (Warsi et al., 2004), barriers still exist and complicate the self-care strategy. Many patients, such as those living with heart failure, are elderly, highly symptomatic with frequent hospitalizations, and without strong financial and social support, making self-management regimens difficult to maintain (Gardetto, 2011). In addition, issues with physical and financial limitations, health literacy, logistical complications, and lack of social and financial support interrupt and prevent effective progression through the self-management process (Bayliss et al., 2003). Without greater investment in addressing these barriers, patients will continue to face the burden behind self-management regimens designed to promote living well with chronic illness.

Social Isolation and Chronic Illness

The social consequence of chronic illness is a significant burden and impacts the ability to live well, especially when a chronic illness presents a visible functional impairment or limitation. In Social Isolation: The Most Distressing Consequence of Chronic Illness (Royer, 1998), the author eloquently describes the essence of social isolation as experienced by many individuals living with disabling chronic illnesses. Individuals living “with long-term health problems are at high risk for lessened and impaired social interactions and social isolation.” Lessened and impaired social contact and a sense of social isolation are among the more detrimental consequences of chronic illness (Royer, 1998):

Impaired social interaction relates to the state in which participation in social exchanges occurs but is dysfunctional or ineffective because of discomfort in social situations, unsuccessful social behaviors, or dysfunctional communication patterns. Indeed, social relationships are frequently disrupted and usually disintegrate under the stress of chronic illness and its management because chronic illnesses often involve disfigurement, limitations in mobility, the need for additional rest, loss of control of some body

functions, and an inability to maintain steady employment. These factors tend to reduce a person’s ability to develop and maintain a network of supportive relationships. As the illness takes up more and more of a person’s time and energy, only the most loyal family members and friends persist in offering support…. [T]he worse the illness (and/or its phases), then the more probability exists that the ill persons will feel or become isolated. Social isolation probably also occurs because family and friends need to withdraw from the ill person to gain emotional distance and protect themselves from a painful situation, particularly if they are unable to help in alleviating the problems of the sufferer. Thus, social isolation can happen in two ways: either the ill person, given the symptoms, unexpected crises, lengthy hospitalizations and convalescence, additional financial burdens, difficult regimens and loss of energy, withdraws from most social contact, or the ill person is avoided or even abandoned by friends and relatives.

The committee thinks that social isolation is not only an important consequence of long-term debilitating chronic illnesses; it is also a burden that cuts across a host of chronic illnesses, thus highlighting the commonality among many of them and presenting an opportunity to develop, disseminate, and evaluate relevant community-based interventions to help people with chronic illness.

Caregivers of Individuals with Chronic Illness

The burden of chronic illness reaches beyond the person with the illness, affecting family members as well, particularly those involved in caregiving. The National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and AARP conducted a national survey of caregivers in the United States to assess the issues they faced in 1997, 2004, and 2009 (NAC and AARP, 2009). The 2009 survey indicated that approximately 28.5 percent—or an estimated 65.7 million people in the United States—served as a family caregiver to an ill or disabled child or adult in the past 12 months. Caregivers of adults spend an average of 18.9 hours per week providing care. And 66 percent of caregivers are women, and women caregivers report more time spent in caregiving than men caregivers.

The burden on informal caregivers is highly variable (see Table 2-1), but as the severity of illness-related impairment increases, caregiver burdens increase as well. Research has documented numerous physical and mental health effects of caregiving. The NAC and AARP report (2009) documents that 17 percent of caregivers consider their health to be fair or poor compared with 13 percent of the general population. Health is particularly affected among low-income caregivers, 34 percent of whom report fair or poor health (NAC and AARP, 2009). Female caregivers in the Nurses’ Health Study were more likely to report a history of hypertension, diabetes,

high cholesterol, and poorer health behaviors (more likely to smoke, eat more saturated fat, and have a higher body mass index). When controlling for these factors, the study found an 82 percent higher incidence of CHD in those who cared for a spouse than in noncaregivers. There was no increased CHD risk among those providing care for an ill parent (Lee et al., 2003). The Caregiver Health Effects Study (CHES) study categorized approximately 800 spouses on the basis of their level of caregiving demand: those with disabled spouses for whom they do not provide care; those who provide care to a disabled spouse but report no caregiver strain; and those who provide care for a disabled spouse and report either physical or emotional strain. These groups were compared with spouses whose partners were not disabled, reporting no difficulty with activities of daily living. After controlling for the presence of illness and subclinical cardiovascular disease in the spouse, those spouses who provided care for a disabled partner and reported caregiver strain had 63 percent higher 4-year mortality than those whose spouses were not disabled (Schulz and Beach, 1999).

Caregivers also report increased symptoms of psychological distress. A meta-analysis of differences between caregivers of older adults with various illnesses and noncaregivers found the largest differences were in depression, stress, self-efficacy, and subjective well-being (Pinquart and Sörensen, 2003). For example, depression among caregivers was higher than in comparable groups of noncaregivers. Depression was higher among caregivers of people with dementia and more common in women than men, spouses than other family caregivers, and caregivers for whom both the perceived and the actual workload are greater (Pinquart and Sörensen, 2003; Schoenmakers et al., 2010). More time spent in caregiving is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (Cannuscio et al., 2004).

Caregiving can have an economic impact as well. Caregivers have a lower labor force participation rate than do adults not involved in caregiving. Effects seem particularly pronounced among women, caregivers who are in poor health themselves, older caregivers, those with more caregiving involvement, immediate family members, caregivers with young children at home, those who cared for people with more limitations, caregivers with lower incomes, and those with less education (Lilly et al., 2007). In all, 58 percent of caregivers of adults are currently employed, with 48 percent working full-time and 10 percent working part-time. And 69 percent report making work changes to accommodate caregiving, such as going in late or leaving early (65 percent), taking a leave of absence (18 percent), turning down a promotion (5 percent), losing job benefits (4 percent), giving up work entirely (7 percent), or retiring early (3 percent) (NAC and AARP, 2009). Caregiving can affect productivity through both absenteeism and presenteeim (decreased productivity while at work) (Giovannetti et al., 2009). Time spent in the physical care of the ill person or in helping them

access health care may increase absenteeism at work. Even when the caregiver is at work, he or she may be distracted by worries about the family member or by spending time dealing with insurance companies, health care records, etc. Furthermore, caregivers may be locked into jobs or prevented from advances or job transfers because of fear of loss of insurance and the need to stay in geographic proximity to the person for whom they provide care.

Economic Consequences of Chronic Illness on the Individual

Chronic illness can wreak havoc on the socioeconomic standing of an individual and his or her family (Jeon et al., 2009). Overwhelming evidence connects lower socioeconomic status with poorer health, putting a large portion of the worldwide population at risk for developing one or more chronic illnesses and further financial hardship (Jeon et al., 2009). The prevalence of chronic illness increases with age, increasing the likelihood of developing a health-related financial and economic burden as an individual gets older (Woo et al., 1997). This burden includes both direct (e.g., out-of-pocket costs of health care) and indirect (e.g., loss of work income) consequences for the individual and/or his or her caregiver or families. In terms of direct consequences, taking a microeconomic approach, a strong association exists between financial stress, disability, and poor physical and mental health and between poverty rates and chronic illness (Jeon et al., 2009). The estimated costs of addressing disability consumed approximately 29 percent of household income and 49 percent for those with severe restrictions (Jeon et al., 2009). Based on these estimates, those with one or more chronic illnesses are six times more likely to sink down to the poverty line than are those without one (Jeon et al., 2009). One Australian study interviewed 52 patients with one or more chronic illnesses and 14 caregivers (or spouses or offspring) of those patients and found that 60 percent of the patients and 79 percent of the caregivers reported experiencing financial difficulties associated with the patients’ chronic illness (Jeon et al., 2009). In all, 84 percent of both groups identified the basic cost of disease management as a primary financial challenge, and 64 percent of both groups reported experiencing financial difficulty related to addressing the patients’ chronic illness and believing that it negatively affected their quality of life (Jeon et al., 2009). Overall, both groups reported financial stress related to affordability of treatment, including out-of-pocket expenses for medications, regular check-ups, and lack of support resources, and affordability of other things, including healthy food, exercise and gym membership, and partaking in social activities (Jeon et al., 2009). In another study, conducted by Teo et al. (2011), 42 percent of the estimated cost burden of COPD was attributed to medical management alone, an expense put in different

weights on the shoulders of the patients and their caregivers. For every dollar spent on fibromyalgia-related health care expenses for its employees, certain employers spent an additional $57 to $143 on direct and indirect costs, masking any evidence of successful treatment (Robinson et al., 2003). For indirect costs alone, Ivanova et al. (2010) compared a group of employees with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) and nontreatment-resistant major depressive disorder and found TRD-likely employees were more likely to have a disability and go through more disability days. Furthermore, although TRD-likely employees had lower rates of medical-related absenteeism, they did go through a higher number of medical-related absenteeism days (Ivanova et al., 2010). From that, TRD-likely employees have more days away from work, creating a loss in productivity for the employee and extra cost for the employer (Ivanova et al., 2010). The indirect consequences of chronic illness, like missing multiple days from work and reduced productivity, increases the risk of losing employment, an event that reinforces financial pressures. Without substantial caregiver, family, or employer support, individuals with one or more chronic illnesses may sink into financial hardship beyond repair.

Effects of Comorbidity

The burden of chronic illness is often compounded by multiple chronic conditions, a situation that is often referred to as multimorbidity or comorbidity. Typically, the term comorbidity is used in the context of an index condition (e.g., cancer) to reflect the impact of other (comorbid) conditions (e.g., heart failure) on prognosis, quality of life, and treatment. Multimorbidity is used to describe MCCs that in aggregate may affect prognosis, quality of life, and treatment. Although most important conditions begin as single diagnostic entities, they may vary in their rate of progression for many reasons other than the primary pathological process. For example, prior conditions may already be present at the time of the occurrence of the new condition, leading to an increased burden for these “new” index conditions. Multimorbidities can contribute to worse outcomes because of complications that affect multiple organ systems, either individually (e.g., macular degeneration may affect vision and osteoarthritis may affect mobility in the same person) or synergistically (e.g., diabetes and hypertension together may accelerate atherosclerotic coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease). Multimorbidities can also complicate treatment regimens, including competing guidelines for care that may confuse people, decreasing adherence or leading to conflicting therapeutic regimens (Boyd et al., 2005; Tinetti et al., 2004). One condition can also interfere with the ability to adhere to treatment for another condition, such as osteoarthritis occurring in individuals with diabetes or cardiovascular disease inhibiting

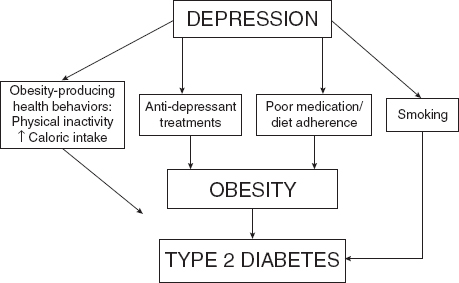

FIGURE 2-4 Depression and the risk of diabetes.

participation in physical activity (Bolen et al., 2009). Primary mental illnesses, such as depression, can increase the risk for medical conditions and the adverse outcomes associated with them (Figure 2-4).

In addition, comorbid depression or anxiety is associated with higher numbers of medical symptoms across a wide variety of illnesses (Katon et al., 2007), in part because of their association with poor adherence to self-care regimens (Lin et al., 2004) and heightened awareness of symptoms (Katon et al., 2001).

Finally, secondary conditions of varying importance and impact can occur because of the debilitating effects of the primary illness. These secondary conditions can take various forms depending on the primary condition and the nature of care, including falls, fractures, depression and other mental consequences, constipation, bedsores, anemia, obesity, sleep disorders, social dysfunction, spasticity, and injuries from various medical devices. These are important not only for their health impact but also because many can be prevented or mitigated with optimal care. Thus, they are also important objects of surveillance in order to define the population burden of chronic disease. This understanding that functional limitation due to one chronic condition may lead to disability through the development of other chronic illnesses provides an opportunity for the prevention of disability. If prevention approaches for people with chronic illness can reduce the risk of developing additional ones, the risk of disability may be reduced as well.

Illness-Environment Interactions

The interaction between persons with chronic illness and their environments can also contribute to the burden and consequences they may experience. For example, a person with late-stage Alzheimer’s disease who has a family caregiver or has the resources to hire a paid caregiver may be able to remain at home, whereas a similar person without this support system is likely to be institutionalized. Similarly, a person with severe rheumatoid arthritis who works in the service industry may be able to continue working by use of voice recognition technology and telecommuting from home, whereas someone who works in construction would be unable to work.

Adverse Effects of Clinical Treatment

Another reason for variation in the rate of development of disability is adverse effects of treatment. Some illnesses may lead to less physical fitness, as with fatigue and muscle atrophy. Moreover, it is well described that patients undergoing varying kinds of clinical care are subject to the adverse effects of that care (IOM, 1999). Adverse effects occur in all elements of care, including medications (Kongkaew et al., 2008); institutionalization, such as hospitalizations and surgical procedures (Michel et al., 2004); and long-term care in various settings (Dhalla et al., 2002). Patients with chronic illnesses, because of extensive and often intensive care experiences, are thus particularly likely to experience adverse effects, even if, in general, their health is better off with the care than without it. Although the severity of adverse effects is sometimes difficult to characterize in detail, care surveillance systems and quality improvement programs clearly demonstrate the general scope of the problem and the need for remediation whenever possible. It is very difficult to identify studies that summarize the net health impact of adverse effects across common chronic illnesses. In complex illnesses, it may be difficult to distinguish between an effect of the illness and the effect of the treatment. Nonetheless, there is an important need to understand the role of adverse effects in affecting the health trajectories of those with chronic illness.

One of the charges to the committee was to suggest a new set of diseases for which to provide increased emphasis in terms of surveillance and chronic disease control efforts. As always, such programmatic emphases may change over time, in part because of the advent of new community or clinical interventions that can improve the lives of individuals with chronic

illness. There are many illnesses from which to choose—in many ways, almost an endless menu of conditions that can lead to suffering and disability.

In addressing the challenges of living well with chronic illness, priorities must be established. Although priority setting in public health and health care is not a new concept, it is a matter of growing importance (Ham, 1997). The combination of constrained resources and increasing demands has led policy makers to address priority setting more directly than in the past. In particular, an explicit part of the committee’s task asked “Which chronic diseases should be the focus of public health efforts to reduce disability and improve functioning and quality of life?”

Fundamentally, the determination of priorities for public health intervention begins with the burden of disease and preventability (Sainfort and Remington, 1995). Other considerations include size of the chronic disease problem, perceptions of urgency, severity of the problem, potential for economic loss, impact on others, effectiveness, propriety, economics, acceptability, legality of solutions, and availability of resources (Vilnius and Dandoy, 1990).

Although there is no correct approach to setting priorities, it is beneficial to have a common planning framework. The framework should

• include multiple perspectives, including patients, providers, employers, and community members;

• use clear and consistent criteria for selecting priorities, whenever possible;

• result in aims and objectives that are clear and feasible;

• consider at what level the decisions are being made (e. g., federal, state, local); and

• include the values of these involved in the decisions.

Despite the challenges involved in setting programmatic priorities, a number of organizations have used these measures and approaches to set health priorities. The Oxford Health Alliance based in the United Kingdom convened a group from around the world of academics, nongovernmental organizations, activists, corporate and industry executives, patients’ rights advocates, health professionals, and others to focus on preventing the worldwide epidemic of chronic diseases (http://www.oxha.org). In 2006, they launched the “3four50” effort (http://www.3four50.com/). This “open space for health” promotes chronic disease prevention by focusing on the three risk factors (poor diet, lack of physical activity, and tobacco use) that lead to four chronic diseases (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic lung diseases, and some cancers) contributing to more than 50 percent of deaths worldwide.

CDC has not set priorities explicitly but has developed the approach

called Winnable Battles to describe public health priorities with large-scale impact on health and with known, effective strategies to intervene (CDC, [d]). The charge under Winnable Battles is to identify optimal strategies and to rally resources and partnerships to accelerate a measurable impact on health. The priority areas for CDC include some that relate directly to chronic disease, including physical activity promotion, obesity elimination, and tobacco control.

Although the federal Healthy People 2010 did not explicitly set national priorities, it established leading health indicators to reflect major public health concerns in the United States (CDC, [b]). These leading health indicators were selected on the basis of their capacity to motivate action, the availability of data to measure progress, and their importance as public health issues. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a report recommending leading health indicators for Healthy People 2020 (2011a). These also include several that pertain to living well with chronic illness. In this chapter, we have explained the additional framework used to select paradigm diseases based on the great variation in their causes, onset, clinical patterns, and outcomes (see Table 2-1). These highlight some of the important dimensions and variations in chronic illnesses that are relevant to patients, the health care system, and the nation, including

a. time course, chronicity, and downstream consequences;

b. enormous variation in etiology and pathogenesis;

c. late-stage manifestations;

d. symptom patterns;

e. functional impairment and disability;

f. secondary consequences, such as falls, sleep disorders, pressure sores;

g. multimorbidity associated with several coexisting chronic illnesses;

h. management burden, both to the patient, the family, and other caregivers and to the health care system;

i. social consequences, such as isolation;

j. economic consequences to the patient and society;

k. impact on the environment; and l. important adverse effects of therapy.

Given such great diversity and a real absence of population data for these dimensions (except possibly in some instances for the most common diseases), the committee took the exemplar approach to highlight disease complexity, diversity, cross-cutting commonalities, and the implications for multidimensional approaches to chronic disease surveillance and control.

The multidimensional approach to selecting the exemplars was derived from the committee’s view that an additional approach to chronic disease

was needed to supplement current approaches for selecting the most common, high-mortality diseases for public health control efforts. The committee’s approach, while appreciating the wisdom and practicality of current approaches, is grounded in other considerations:

1. Current approaches to selecting diseases for control activity based on such criteria as prevalence, mortality, disability, and economic cost to the care system are useful, but these criteria are often orthogonal to each other, and thus the selection algorithm is in several ways arbitrary.

2. Current approaches to selecting diseases for public health focus inadequately address the great variation in clinical manifestations and trajectories that make public health approaches complex and challenging.

3. Current approaches are not inclusive of the large number of less common illnesses that impact individuals and communities in important ways.

4. The recognized problem of MCCs has not been adequately addressed in current disease control activities.

For these reasons, the committee recommended an “exemplar” approach to address some of these perceived inadequacies. This approach starts with a framework, presented in this chapter, that begins not with a specific set of conditions or criteria for them but with a broad set of clinical manifestations and other consequences experienced by individuals with chronic illness. The committee thinks that this framework highlights a new and alternative approach to public health chronic disease control. The exemplars did not come from a list. Rather, they come from the clinical and research experience of committee members and were chosen to highlight some important features of chronic diseases that have received less emphasis in the past, including

1. Great diversity in clinical manifestations within and among chronic diseases and the great variation in their manifestations as illnesses continue their natural histories.

2. The inclusion of illnesses that can be manifest across the life course, raising the possibility of public health interventions that may be effective at various life stages of disease. The life course approach also more effectively deals with the occurrence of recurrent or additional different conditions (MCCs).

3. The highlighting of important psychological and social consequences that come with many chronic illnesses, including individuals

with primary mental illnesses and those that are secondary to other conditions.

4. The highlighting of the chronic, multiple, degenerative age-related conditions, for which public health approaches are perhaps less well developed.

In addition, the committee endorses CDC’s emphasis on “winnable battles” and thinks that the exemplar approach will help identify new types of battles and population-based interventions in the management and control of chronic diseases. Accordingly, the committee has selected nine emblematic diseases, health conditions, and impairments, because together they encompass and flesh out the range of key issues that affect the quality of life of patients with the full spectrum of chronic illnesses. More importantly, if interventions, policies, and surveillance were developed to address these nine diseases, they would also address diseases similar to them. The exemplar approach also avoids the trap of pitting one disease against another in competing for resources and attention. Rather, it conceptualizes the commonalities across diseases with the intent of developing strategies that benefit all affected by the vast array of chronic diseases.

Thus, we have sampled from the different patterns (clinical manifestations and trajectories) of chronic diseases in order to represent the important dimensions of varying chronic disease manifestations. The nine clinical clusters—not all specific and individual diseases and conditions in the literal sense—are described below, with brief comments on their epidemiology and community impact. Each represents an important challenge to public health, in addition to those diseases that have received more attention, namely, the diseases responsible for much of morbidity and mortality and significantly add to health care cost in the United States and other developed countries. The nine are arthritis, cancer survivorship, chronic pain, dementia, depression, diabetes mellitus type 2, posttraumatic disabling conditions, schizophrenia, and vision and hearing loss.

Arthritis

Arthritis is the term used to describe more than 100 rheumatic diseases and conditions that affect joints, tissues surrounding the joints, and other connective tissue.

Arthritis is a highly prevalent condition. It is estimated that 50 million adults in the United States (approximately one in five) report doctor-diagnosed arthritis (CDC, 2011a). Arthritis is more prevalent in older age groups, women, individuals who are overweight, and individuals with lower socioeconomic status. It affects members of all racial and ethnic groups (AAOS, 2008; CDC, 2011a; Dalstra et al., 2005). Although arthritis

is more prevalent in older age groups, with half of adults age 65 and older reporting arthritis, nearly two-thirds of the adults reporting doctor-diagnosed arthritis are younger than age 65 (AAOS, 2008). As the U.S. population ages, the prevalence of arthritis is projected to increase over current levels to 67 million by 2030 (CDC, 2011a; Hootman and Helmick, 2006).

In addition to being one of the most prevalent chronic illnesses, arthritis is the leading cause of disability (McNeil and Binette, 2001) and one of the leading causes of work limitations (Stoddard et al., 1998). In 2008, 29 million persons over age 18, 13 percent of all adults in the United States, had self-reported activity limitations attributable to arthritis (AAOS, 2008). As with the frequency of arthritis, the prevalence of arthritis-attributable activity limitations increases as people age. Among adults age 65 and older, 28 percent reported activity limitations attributed to arthritis in 2008 (AAOS, 2008). In terms of work disability, 5.3 percent of all U.S. working-age adults (age 18 to 64) reported work limitations due to arthritis (CDC, 2011a).

Significant personal and societal burdens result from the high prevalence of arthritis and limitations and disability associated with it. In 2004, the estimated annual cost of medical care for arthritis and joint pain was $281.5 billion (AAOS, 2008). Of this amount, $37.3 billion is estimated to be incremental cost that can be directly attributed to arthritis and joint pain (AAOS, 2008). The indirect cost of arthritis and related rheumatic conditions due to lost earnings was estimated to be $54.3 billion in 2004 (AAOS, 2008). This includes an estimated $22 billion as a result of OA, $17.1 billion from RA, and $15.2 billion from gout (AAOS, 2008). These costs do not include the intangible costs of an individual forgoing the activities that they and society value.

Arthritis, in particular, is often comorbid with other conditions. A total of 24 percent of adults with arthritis have heart disease, 19 percent have chronic respiratory illnesses, and 16 percent have diabetes (CDC, [a]). Conversely, 57 percent of people with heart disease and 52 percent of people with diabetes have arthritis.

The most commonly occurring type of arthritis is osteoarthritis (OA), characterized by progressive damage to the cartilage and other joint tissues (AAOS, 2008). OA frequently affects the hands, knees, and hips. Other forms of arthritis that occur frequently include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), fibromyalgia, and gout (CDC, 2011a). Pain, stiffness, and swelling are common symptoms for these conditions, and some forms of arthritis, such as RA and SLE, also have a systemic component whereby multiple organs can be affected (Arthritis Foundation, 2008). The prevalence of OA can be estimated in terms of either radiographic changes related to the presence of OA or as symptomatic

OA, which includes having pain, aching, or stiffness in the same joint that shows radiographic OA (AAOS, 2008). More than 27 million U.S. adults have OA, and it is estimated that half of all adults will develop symptomatic OA of the knee at some point their lives (Arthritis Foundation and CDC, 2010; Murphy et al., 2008). In addition to being more common in women and obese individuals, OA is more common in certain occupations, including mining, construction, agriculture, and certain segments of the service industry (Arthritis Foundation and CDC, 2010). Approximately 25 percent of people with knee OA have difficulty performing activities of daily living and also have pain on ambulation (Arthritis Foundation and CDC, 2010). OA interferes with working adults’ (age 18 to 64) work productivity, and their employment rates are lower than among adults without arthritis (Arthritis Foundation and CDC, 2010). It is estimated that $3.4 to 13.2 billion is spent on job-related OA costs per year (Arthritis Foundation and CDC, 2010). In terms of direct medical costs, in 2004, OA resulted in more than 11 million physician and outpatient visits, 662,000 hospitalizations, and more than 632,000 total joint replacements (Arthritis Foundation and CDC, 2010).

RA, the second most common type of arthritis, is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes pain, stiffness, swelling, and limitation in the motion and function of multiple joints. The prevalence of RA is estimated to be around 0.6 percent of the population over the age of 17, approximately 1.3 million adults in 2005 (AAOS, 2008). RA is twice as common in women as in men. In 2006, RA accounted for 2.9 million ambulatory care visits and 15,400 short-stay hospitalizations (AAOS, 2008). This estimate does not account for hospitalizations related to arthritis treatment complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding related to the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and it does not account for hospitalizations related to orthopedic procedures (AAOS, 2008).

In summary, arthritis and related rheumatic conditions have a significant impact on the quality of life of affected individuals, with substantial physical, psychosocial, and economic consequences.

Cancer Survivorship

The number of cancer survivors in the United States is on the rise; in 2007 there were nearly 12 million people alive in the United States with a previous cancer diagnosis, up from approximately 3.5 million in 1971 (NCI, 2011; Rowland et al., 2004). Survivors older than 65 comprise 7 million of the 12 million survivors, the largest survivor age group (NCI, 2011). With the aging of the U.S. population, this group of cancer survivors 65 is projected to grow faster than other age groups (Smith et al., 2009). In addition, cancer is expected to increase more rapidly in all nonwhite racial

and ethnic groups; between 2000 and 2030, cancer cases are expected to increase by 31 percent in whites, and by 99 percent in nonwhite racial and ethnic groups (Smith et al., 2009).

Cancer is a serious and often life-threatening disease, requiring difficult and intensive treatments that may leave survivors with lasting negative health consequences, despite a stabilization or elimination of their cancer. Cancer treatment can affect the health, functioning, and well-being of survivors. These can be divided into long-term effects (side effects/complications that begin during treatment and persist beyond the end of treatment) or late effects (side effects/treatment toxicities that are unrecognized or subclinical at the end of treatment but emerge later because of developmental processes), decreased ability to compensate as the survivor ages, or organ senescence (IOM and NRC, 2006). Nearly every organ system and tissue has the potential to be affected by cancer treatment, including cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, lymphatic, bone, endocrine, gastrointestinal, hematologic, hepatic, immune, ophthalmologic, and renal systems. A thorough description of the medical and psychosocial effects of cancer can be found in the IOM report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition (IOM and NRC, 2006), but some examples of lasting and late effects are described below.

Highly effective and frequently used anthracycline chemotherapy can cause left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure (Pinder et al., 2007; Towns et al., 2008). For example, Pinder et al. (2007) found a 26 percent increased risk of congestive heart failure in breast cancer survivors between the ages of 66 and 70 who received anthracycline-based chemotherapy, compared with those who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Newer targeted therapies, such as trastuzumab (Herceptin), bevacizumab, and sunitinib, also can have detrimental effects on the heart (Chu et al., 2007; Floyd et al., 2005).

Cancer surgery that removes lymph nodes (as well as radiation therapy to the nodes) can lead to lymphedema, the collection of fluid in a limb or other body part due to impedance of the flow of fluid in the lymphatic system, leading to swelling, pain, and loss of function. Lymphedema is frequently a concern for breast cancer survivors (NCI, [a]); it can also affect survivors of melanoma, gynecologic, genitourinary, and head and neck cancers (Cormier et al., 2010).

Radiation therapy can damage healthy tissue as well as tumor cells; effects on healthy tissue may involve cell killing through DNA double-strand breaks but also increased risk of fibrosis and impaired function in blood and lymph vessels. The effects of the damage depend on the area that was irradiated; for example, survivors who have radiation treatment for gynecologic cancers report 12 times the risk of bowel incontinence compared with controls who have not had cancer (Lind et al., 2011).

Other aftereffects of cancer are prevalent but are more difficult to tie to specific treatment toxicities. Nevertheless, cancer survivors report persistent problems with fatigue, sleep difficulties, and psychological distress, particularly anxiety about recurrence (Bower et al., 2008). Furthermore, survivors are at increased risk of second primary tumors, either because of host susceptibility or treatment effects, necessitating careful surveillance for cancer recurrence and detection of new cancer (IOM and NRC, 2006).

More than ever before, cancer is being managed like a chronic disease. In part this is due to the late effects described above. However, it is also because the treatment of cancer has been extended for many cancer sites. For example, women with estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer receive the recommendation to take estrogen-suppressing therapy for 5 years, and in some cases survivors experience troublesome side effects, such as joint and muscle pain (Mao et al., 2009). The treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia has been revolutionized by the use of imatinib, a targeted agent that has relative low toxicity but is taken for an indefinite period of time to keep the disease at bay. Even metastatic disease, which has historically resulted in a rapid decline and death, has more treatment options, so that for certain disease sites, such as breast and colon, survivors with metastatic disease are living longer. Survivors with metastatic illness often stay on a therapy until it stops working or the side effect burden becomes too great, when they may switch to another therapy.

Lasting and late effects, as well as side effects from continuous treatment, have negative repercussions for health and functioning in a range of areas. Results from analyses of the National Health Interview Survey show that cancer survivors are more likely to rate their health as fair or poor (31 percent) than the noncancer controls (17.9 percent). They also are more likely than controls to report functional limitations, including needing help with ADL (cancer survivors, 4.9 percent; controls, 3 percent), instrumental activities of daily living (cancer survivors, 11.4 percent; controls, 6.5 percent), and any limitation (cancer survivors, 36.2 percent; controls, 23.8 percent). Survivors are more likely to report being unable to work and being more limited in the amount of type of work they can do because of health (Yabroff et al., 2004).

These functional limitations persist long after diagnosis; one study found that the odds of having a functional limitation in cancer survivors versus controls was similar for survivors within 5 years of diagnosis and more than 5 years after diagnosis; in an analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Ness et al. (2006) found that the odds of physical performance limitations were 85 percent higher in survivors within 5 years of diagnosis compared with adults who had not had cancer, and by 49 percent among those who were 5 or more years from diagnosis after controlling for sex, age, race/ethnicity, and annual house-hold

income. Age and comorbid health problems also complicate the health status of cancer survivors.

Because age is one of the strongest risk factors for cancer, most cancer survivors are older (60 percent are age 65 or older; NCI, 2011), and 42.1 percent have one or more chronic illnesses other than their cancer (compared with 19.7 percent among those who have not had cancer (Hewitt et al., 2003). Approaches to living well need to take into account issues of aging and MCCs.

Chronic Pain

Pain varies in severity and locale. It can be mild or acute, but in many cases it can be chronic. Some of the most commonly occurring chronic pain originates from headaches, the lower back, cancer, arthritis, peripheral nerve damage, and an unknown source (NINDS, [a]). Approximately 100 million adults within the United States suffer from chronic pain (IOM, 2011b). The different forms and origins of pain vary in prevalence. As various studies have shown, however, chronic pain is on the rise, continuing to affect both men and women and individuals of all races and ethnicities. The level of chronic pain experienced worldwide is expected to continue to increase as the population ages and rates of obesity and physical inactivity leading to pain-related conditions soar (Phillips and Harper, 2011). For example, a survey of North Carolina residents found that the prevalence of chronic low back pain increased from 3.9 to 10.2 percent between 1992 and 2006 (Freburger et al., 2009). Similarly, the number of cancer diagnoses continues to rise, with 50 to 90 percent of patients suffering from cancer- and treatment-related pain (WHO, 2008; Zaza and Baine, 2002). Recent literature suggests that racial and ethnic minorities, including African Americans and Hispanics, have greater chances of going undertreated for pain than white Americans (Green et al., 2003).

Chronic pain may result from a previous injury or medical condition, or it may have no known cause (NINDS, [a]). It can be considered a disease, as it has the potential to increasingly damage the nervous system over time (IOM, 2011b). Chronic pain often occurs with a variety of comorbidities. In many instances, it occurs in conjunction with other pain-inducing conditions, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and vulvodynia (NINDS, [a]). Furthermore, it often occurs in conjunction with other mental conditions, such as depression and multiple mood and anxiety disorders, including panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (Bair et al., 2003; McWilliams et al., 2003).

Chronic pain and musculoskeletal disorders typically score lowest in terms of quality of life (Phillips and Harper, 2011). Depending on the type and severity of pain experienced, chronic pain can cause a substantial

amount of disablement. Even differing levels of pain with the same origin, such as the low back, can lead to differing levels of disablement. Low back pain symptoms range from being specific and part of a specific pathology to being localized or part of a widespread, unknown pathology (Wormgoor et al., 2006). As pain decreases in specificity, patients often focus on it more, resulting in greater distress and dissatisfaction with life factors (Wormgoor et al., 2006). It has also been found, however, that as pain increases in specificity, loss of function and activity limitations increase (Wormgoor et al., 2006). In either form, the studied group illustrates that pain leads to negative consequences in functioning. In another study, individuals who suffer from chronic daily headaches demonstrated significant decreases in all health-related markers on the SF-36 health survey compared with healthy individuals, with the highest decreases found in role, physical, bodily pain, vitality, and social functioning (Guitera et al., 2002). In the population studied, chronicity of pain had greater influence than intensity of pain on quality of life (Guitera et al., 2002). A review of 52 studies conducted by Jensen and colleagues (2007) found solid evidence that the presence and severity of chronic neuropathic pain is associated with impairments in physical, emotional, role, and social functioning.

The burden associated with chronic pain reaches far beyond the individual suffering from it (Phillips and Harper, 2011). Significant functional disablement translates into substantial financial outcomes, reaching beyond the individual to the individual’s caretaker and family, community, and country. Evidence shows that chronic pain has a substantial impact on productivity levels, as it results in higher rates of absenteeism and the likelihood of leaving the workforce (Phillips and Harper, 2011). One study showed that, among spouses of individuals suffering from chronic pain, 35 percent had to take on extra work to support the family, 43 percent had to take time off to care for the pain sufferer, 37 percent had to assume greater financial-related task responsibility, and 89 percent had to assume greater household responsibility (Hahn et al., 2001). Mechanical low back pain ranks fourth out of the top 10 most costly physical health conditions affecting American businesses today in terms of total medical expenses, medical-related absences, and short-term disability payments (Goetzel et al., 2003). Ricci and colleagues (2005) estimated the annual lost productive work time cost due to arthritis in the U.S. workforce at around $7.11 billion, with 65.7 percent attributable to the 38 percent of workers with pain exacerbations. In a previous IOM report, it was estimated that the annual cost of chronic pain in the United States runs anywhere from $560 to $635 billion (IOM, 2011b).

In the battle against the development of chronic pain, a myriad of primary preventive interventions have been tested. Psychological factors are tightly connected to the development of costly disability (Linton and

BOX 2-1

Findings from Relieving Pain in America

• Need for interdisciplinary approaches. Given chronic pain’s diverse effects, interdisciplinary assessment and treatment may produce the best results for people with the most severe and persistent pain problems.

• Importance of prevention. Chronic pain has such severe impacts on all aspects of the lives of its sufferers that every effort should be made to achieve both primary prevention (e.g., in surgery for broken hip) and secondary prevention (of the transition from the acute to the chronic state) through early intervention.

• Wider use of existing knowledge. While there is much more to be learned about pain and its treatment, even existing knowledge is not always used effectively, and thus substantial numbers of people suffer unnecessarily.

SOURCE: IOM, 2011b.

Ryberg, 2001). Because of this, cognitive-behavioral interventions often have positive results in preventing further disability (Linton and Ryberg, 2001). Linton (2002) showed that it is possible to identify patients who suffer from musculoskeletal pain at high risk for developing pain-related disability and to successfully lower their risk of work disability through cognitive-behavioral intervention. Once disability appears, however, similar therapy methods still appear successful. Linton and Ryberg (2001) provided evidence of this as study participants suffering from chronic neck and back pain undergoing cognitive-behavioral group intervention showed significantly better results in terms of fear-avoidance beliefs, number of pain-free days, and use of sick leave.

Relevant findings from the IOM’s report Relieving Pain in America are presented in Box 2-1.

Dementia

Dementia affects 13 percent of persons age 65 and older and up to 43 percent of persons age 85 and older (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011a). In the United States, an estimated 5.4 million persons are affected by Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011b). Moreover, the burden of dementia is even higher, as Alzheimer’s disease accounts for only 60 to 80 percent of cases of dementia. Although dementia is commonly thought of as a condition of the elderly, an estimated 220,000 to 640,000 persons under age 65 are also affected (Alzheimer’s Association, 2006). Studies in

nursing homes indicate that 26 to 48 percent of residents have dementia (Magaziner et al., 2000; O’Brien and Caro, 2001).

These patients and their families have needs far beyond those of healthier older persons and those who have chronic illnesses that do not affect memory. In many respects, dementia is a prototypic chronic disease that requires both medical and social services to provide a high quality of care and to prevent complications, including repeated hospitalizations (Chodosh et al., 2004) and high care costs. In 2011, Medicare and Medicaid programs for people with Alzheimer’s disease were estimated at $130 billion (Okie, 2011). The clinical manifestations of dementia are protean and devastating and include cognitive impairment, immobility and falls, swallowing disorders and aspiration pneumonia, urinary and fecal incontinence, and behavioral disturbances (e.g., agitation, aggression, depression, hallucinations), which lead to caregiver stress and burnout.

Most cases of dementia start insidiously, often beginning with mild memory symptoms and progressing to mild cognitive impairment when deficits can be demonstrated on clinical examination. By the time of diagnosis of dementia, there are deficits in other dimensions of cognition (e.g., language, visual-spatial, executive function) in addition to memory that interfere with functioning. As the illness progresses, patients progressively lose memory and function and, at the late stages, may have no or unintelligible speech. Patients spend more years with severe dementia than in earlier stages (Arrighi et al., 2010). Almost all patients with dementia have at least one coexisting medical illness, especially coronary heart disease (26 percent), diabetes (23 percent), congestive heart failure (16 percent), and cancer (13 percent). Persons with dementia and these illnesses have more hospital stays than those with the same illnesses without dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011a). Although dementia has variable rates of progression and lengths of survival after diagnosis, the median is 4 to 8 years (Brookmeyer et al., 2002; Ganguli et al., 2005; Helzner et al., 2008; Larson et al., 2004).

Dementia is a particularly devastating illness because the clinical manifestations affect the ability to maintain function and manage other chronic illnesses. Moreover, as dementia progresses, its complications often result in caregiving needs that may overwhelm the care of other preexisting and new chronic illnesses.

Nationwide in 2010, an estimated 15 million caregivers provided 17 billion hours of care worth $202 billion (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011a). And 80 percent of care provided in the home for patients with dementia is delivered by family caregivers who provide ADL and IADL functions, manage safety issues and behavioral symptoms, and coordinate medical and supportive care. Although these caregivers report positive feelings about this role, 61 percent rated the emotional stress of caregiving as high or very

high (Alzheimer’s Association, 2011a), and approximately one-third report symptoms of depression (Taylor et al., 2008; Yaffe et al., 2002). The physical health of caregivers may also be affected. For example, caregivers of dementia patients have increased rates of coronary heart disease (Vitaliano et al., 2002).

Current medications can sometimes slow the course of decline of Alzheimer’s disease and some other dementias, but they do not cure the disorder. The addition of a dementia care manager to primary care practices can improve quality of care, reduce complications of aggression and agitation, and prevent caregiver depression (Callahan et al., 2006). Similarly, a disease management program led by care managers has been shown to improve patient health-related quality of life, overall quality of patient care, caregiving quality, social support, and level of unmet caregiving assistance needs (Vickrey et al., 2006). In addition, partnering with local Alzheimer’s Association chapters can improve the quality of dementia care (Reuben et al., 2010).

Research is needed on models of care that link health care systems with community-based organizations to provide the wide range of services needed by patients with dementia. This research needs to include developing payment structures for community-based social services that are necessary to provide comprehensive care for persons with dementia. As stated in the IOM report Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce (2009), “research is needed for the development and promulgation of technological advancements that could enhance an individual’s capacity to provide care for older adults including the use of ADL technologies and information technologies that increase the efficiency and safety of care and caregiving.”

Depression

Major depression is a common chronic illness that causes a substantial degree of impairment and disability (Michaud et al., 2006). National studies in the United States found a point prevalence of about 7 percent in 2001 and 2002 (Compton et al., 2006). Cohort studies found that the lifetime prevalence of major depression is 17 percent (National Comorbidity Survey Replication, 2007). The prevalence among women is about twice that among men (Murphy et al., 2000), and the lifetime prevalence is higher for whites than for African Americans (Williams et al., 2007). Both point prevalence and lifetime prevalence of major depression is higher for younger than for older persons (Kessler et al., 2010). However, depression is more common in older persons with a greater number of chronic illnesses, including those with disabilities (Charney et al., 2003; Lebowitz et al., 1997; Lyness et al., 2006).

Major depression causes a large burden of suffering on both individuals and society. One extensive study of the burden of chronic illnesses in the United States for 1996 found that major depression was the leading cause of lost disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for people age 25 to 44 (Michaud et al., 2006). Another study of a nationally representative sample of people age 18 and older investigated the association between life role disability in the previous 30 days and 30 different chronic illnesses. Musculoskeletal illnesses and depression had the largest effects on disability of any of the other illnesses (Merikangas et al., 2007). Depression is also a frequent complicating factor for many other chronic illnesses. It frequently accompanies such illnesses as diabetes, disabling osteoarthritis, and cognitive impairment. One study found that 71 percent of Medicare recipients with depression have four or more other chronic illnesses (Wolff and Boult, 2005).