Message Environments:

Goal, Recommendation, Strategies, and Actions for Implementation

Goal: Transform messages about physical activity and nutrition.

Recommendation 3: Industry, educators, and governments should act quickly, aggressively, and in a sustained manner on many levels to transform the environment that surrounds Americans with messages about physical activity, food, and nutrition.

Strategy 3-1: Develop and support a sustained, targeted physical activity and nutrition social marketing program. Congress, the Administration, other federal policy makers, and foundations should dedicate substantial funding and support to the development and implementation of a robust and sustained social marketing program on physical activity and nutrition. This program should encompass carefully targeted, culturally appropriate messages aimed at specific audiences (e.g., tweens, new parents, mothers); clear behavior-change goals (e.g., take a daily walk, reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among adolescents, introduce infants to vegetables, make use of the new front-of-package nutrition labels); and related environmental change goals (e.g., improve physical environments, offer better food choices in public places, increase the availability of healthy food retailing).

For Congress, the Administration, and other federal policy makers, working with entertainment media, potential actions include

• providing a sustained source of funding for a major national social marketing program on physical activity and nutrition; and

• designating a lead agency to guide and oversee the federal program and appointing a small advisory group of physical activity, nutrition, and marketing experts to recommend message and audience priorities for the program; ensuring that the program includes a balance of messages on physical activity and nutrition, and on both individual behavior change and related environmental change goals; and exploring all forms of marketing, including message placement in popular entertainment, viral and social marketing, and multiplatform advertising—including online, outdoor, radio, television, and print.

For foundations, working with state, local, and national organizations and the news media, potential actions include

• enhancing the social marketing program by encouraging and supporting the news media’s coverage of obesity prevention policies through the development of local and national media programs that engage individuals in the civic debate about local, state, and national-level environmental and policy changes, including such steps as providing resources to enable journalists to cover these issues and enhancing the expertise of local, state, and national organizations in engaging the news media on these issues.

Strategy 3-2: Implement common standards for marketing foods and beverages to children and adolescents. The food, beverage, restaurant, and media industries should take broad, common, and urgent voluntary action to make substantial improvements in their marketing aimed directly at children and adolescents aged 2-17. All foods and beverages marketed to this age group should support a diet that accords with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans in order to prevent obesity and risk factors associated with chronic disease risk. Children and adolescents should be encouraged to avoid calories from foods that they generally overconsume (e.g., products high in sugar, fat, and sodium)

and to replace them with foods they generally underconsume (e.g., fruits, vegetables, and whole grains).

The standards set for foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents should be widely publicized and easily available to parents and other consumers. They should cover foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents aged 2-17 and should apply to a broad range of marketing and advertising practices, including digital marketing and the use of licensed characters and toy premiums. If such marketing standards have not been adopted within 2 years by a substantial majority of food, beverage, restaurant, and media companies that market foods and beverages to children and adolescents, policy makers at the local, state, and federal levels should consider setting mandatory nutritional standards for marketing to this age group to ensure that such standards are implemented.

Potential actions include

• all food and beverage companies, including chain and quick-service restaurants, adopting and implementing voluntary nutrition standards for foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents;

• the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative and National Restaurant Association Initiative, as major self-regulatory marketing efforts, adopting common marketing standards for all member companies, and actively recruiting additional members to increase the impact of improved food marketing to children and adolescents;

• media companies adopting nutrition standards for all foods they market to young people; and

• the Federal Trade Commission regularly tracking the marketing standards adopted by food and beverage companies, restaurants, and media companies.

Strategy 3-3: Ensure consistent nutrition labeling for the front of packages, retail store shelves, and menus and menu boards that encourages healthier food choices. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S.

Department of Agriculture (USDA) should implement a standard system of nutrition labeling for the front of packages and retail store shelves that is harmonious with the Nutrition Facts panel, and restaurants should provide calorie labeling on all menus and menu boards.

Potential actions include

• the FDA and USDA adopting a single standard nutrition labeling system for all fronts of packages and retail store shelves, the FDA and USDA considering making this system mandatory to enable consumers to compare products on a standard nutrition profile, and the guidelines provided by the Institute of Medicine (2011a) being used for implementation; and

• restaurants implementing the FDA regulations that require restaurants with 20 or more locations to provide calorie labeling on their menus and menu boards, and the FDA/USDA monitoring industry for compliance with this policy.

Strategy 3-4: Adopt consistent nutrition education policies for federal programs with nutrition education components. USDA should update the policies for Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) and the policies for other federal programs with nutrition education components to explicitly encourage the provision of advice about types of foods to reduce in the diet, consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Potential actions include

• removing the restrictions on the types of information that can be included in SNAP-Ed programs and encouraging advice about types of foods to reduce;

• disseminating, immediately and effectively, notification of the revised regulations, along with authoritative guidance on how to align federally funded nutrition education programs with the Dietary Guidelines; and

• ensuring that such full alignment of nutrition education with the Dietary Guidelines applies to all federal programs with a nutrition education component, particularly programs that target primary food shoppers in low-income families (e.g., the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC]).

NOTE: Instruction in food and nutrition for children and adolescents in schools is covered in Chapter 9, on school environments.

Each day, Americans of all ages are surrounded by an environment replete with messages about physical activity and food: advertising on television, billboards, and cell phones; product placements in movies and video games; product packaging at grocery stores and on the kitchen table; public service campaigns; and nutrition and physical activity classes provided through schools and government programs. Some messages are explicit, making direct appeals (e.g., soft drink ads or public service messages), and some are implicit, operating more on a subconscious level (e.g., when people pass a familiar fast-food chain every day on the way to school or come to expect the local sports team to be sponsored by a chain restaurant). Indeed, the food and beverage and restaurant industries have invested heavily in extensive research into understanding complex, deep-seated motivation.

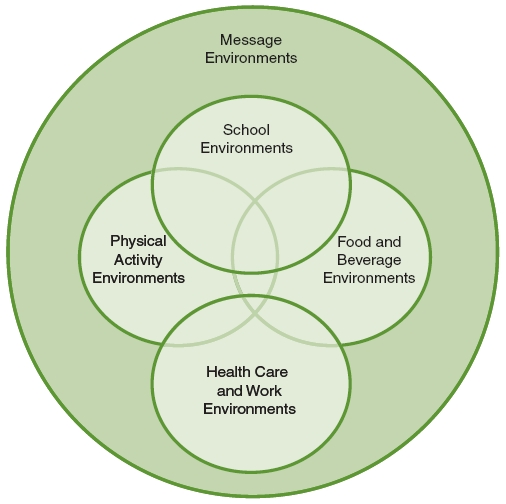

As discussed in the preceding chapters, what is available in people’s daily environment circumscribes their choices: for example, whether there are safe playgrounds within walking distance or which drinks are in the vending machine. But what is promoted in people’s daily environment influences their choices as well. It is the message environments in which people live (highlighted in Figure 7-1) that help create the expectation that a “treat” involves a fast-food outlet or that drinking a particular soda is a sign of a hip or active lifestyle. This chapter addresses these message environments, including marketing and the provision of nutrition education within federal programs with nutrition education components; Chapter 9 covers instruction in food and nutrition for children and adolescents in schools.

FIGURE 7-1 Five areas of focus of the Committee on Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention.

NOTE: The area addressed in this chapter is highlighted.

Industry, educators, and governments should act quickly, aggressively, and in a sustained manner on many levels to transform the environment that surrounds Americans with messages about physical activity, food, and nutrition.

While changing the physical environment is critical to accelerating progress in preventing obesity—whether by expanding bike paths or building more grocery stores—equally important is changing the message environments in which people function every day. These environments take many forms: advergames on popular children’s websites; brand ambassadors sent to offer free products to students on

their first day of college; public service campaigns on billboards and bus shelters; product placements in video games or reality television shows; health messages embedded in children’s educational television shows; nutrition labeling on food packages and menu boards; physical activity and eating behaviors modeled on popular sitcoms; the products that are placed at children’s eye level in grocery stores; the brand icons, celebrity endorsements, and character tie-ins featured on product packages; the mobile ads texted to teenagers; the information provided in school health classes or in education programs for those receiving public assistance; and what a doctor does or does not say about physical activity and diet during an annual checkup.

Many different actors influence these message environments. Exerting this influence on a large scale costs money, and most of those who make that investment do so not because they care about the health outcomes they may be influencing but because they have a financial stake in the choices people make: whether a young boy chooses to play a video game with friends online instead of a softball game with his neighbors, or whether a young mother decides that the best reward for her daughter’s good grades at school is a meal at her favorite fast-food restaurant instead of a home-cooked dinner.

The committee therefore recommends that actors at all levels—the food and beverage industry, the entertainment and sports industries, educators, and government at all levels—do their part to contribute to the transformation of the message environments that is needed to accelerate progress in obesity prevention. Four strategies and potential actions for implementing this recommendation are provided. These strategies and actions are detailed in the remainder of this chapter. (As noted above, the strategy of providing food literacy in schools, along with potential actions for implementing this strategy, is included in Chapter 9.) Indicators for measuring progress toward the implementation of each strategy, organized according to the scheme presented in Chapter 4 (primary, process, foundational) are presented in a box following the discussion of that strategy.

STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

Congress, the Administration, other federal policy makers, and foundations should dedicate substantial funding and support to the development and implementation of a robust and sustained social marketing program on physical

activity and nutrition. This program should encompass carefully targeted, culturally appropriate messages aimed at specific audiences (e.g., tweens, new parents, mothers); clear behavior-change goals (e.g., take a daily walk, reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among adolescents, introduce infants to vegetables, make use of the new front-of-package nutrition labels); and related environmental change goals (e.g., improve physical environments, offer better food choices in public places, increase the availability of healthy food retailing).

For Congress, the Administration, and other federal policy makers, working with entertainment media, potential actions include

• providing a sustained source of funding for a major national social marketing program on physical activity and nutrition; and

• designating a lead agency to guide and oversee the federal program and appointing a small advisory group of physical activity, nutrition, and marketing experts to recommend message and audience priorities for the program; ensuring that the program includes a balance of messages on physical activity and nutrition, and on both individual behavior change and related environmental change goals; and exploring all forms of marketing, including message placement in popular entertainment, viral and social marketing, and multiplatform advertising—including online, outdoor, radio, television, and print.

For foundations, working with state, local, and national organizations and the news media, potential actions include

• enhancing the social marketing program by encouraging and supporting the news media’s coverage of obesity prevention policies through the development of local and national media programs that engage individuals in the civic debate about local, state, and national-level environmental and policy changes, including such steps as providing resources to enable journalists to cover these issues and enhancing the expertise of local, state, and national organizations in engaging the news media on these issues.

Context

Americans of all ages, including children and adolescents, are exposed to a tremendous amount of well-financed and expertly crafted marketing and advertis-

ing messages designed to encourage food and beverage consumption (Cheyne et al., 2011; FTC, 2008; Harris et al., 2009, 2010). The most frequently marketed foods and beverages are often of lower nutritional value and tend to be from the food groups Americans are already overconsuming (Cheyne et al., 2011; Grotto and Zied, 2010; Harris et al., 2010; Harrison and Marske, 2005; IOM, 2006). For example, a 2009 study found that approximately 87 percent of the 7.9 food and beverage ads seen by children aged 6-11 on television each day were for products high in saturated fat, sugar, or sodium (Powell et al., 2011). Moreover, many of these advertisements include incentives such as premiums, sweepstakes, and contests to induce purchases and consumption. One study, for example, found that 14 percent of fast-food ads and 17 percent of dine-in and delivery restaurant messages targeting children included at least one premium offer (Gantz et al., 2007). In addition, American consumers are exposed to a vast amount of marketing that promotes sedentary activities (such as television viewing). For example, Gantz and colleagues (2007) found that children aged 8-12 viewed approximately 8,400 promotions for upcoming television shows and approximately 5,000 ads for entertainment media products each year.

The news media also are a key part of the message environments that surround Americans. A recent survey found that 83 percent of Americans watch local or national television news, read a newspaper, listen to news radio, or visit an online news site daily (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 2010). The national broadcast network evening news programs together attract approximately 21.6 million viewers per night (Guskin et al., 2011). News media continue to play an essential role in highlighting the issues that are seen as legitimate or important for public consideration and in informing citizens on those topics. In describing the potential role of the news media in public health issues, a previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee concluded that “the more coverage a topic receives in the news, the more likely it is to be a concern of the public. Conversely, issues not mentioned by the media are likely to be ignored or to receive little attention” (IOM, 2002, p. 308). Too often, however, news coverage of physical activity and nutrition focuses on strategies for individuals to eat better and move more. This focus on the individual can obscure the importance of broader environment or policy changes (Lawrence, 2004; Woodruff et al., 2003).

Foods, beverages, and entertainment media are marketed to children, adolescents, and adults because for-profit entities stand to benefit financially from the investment in advertising. No similar investments are made in marketing messages about fitness and nutrition, in part because there are no entities with a similarly

clear financial stake in promoting those messages (Gantz et al., 2007). For example, in 2005 children aged 8-12 saw an average of 158 public service announcements (PSAs) on fitness or nutrition in that one year compared with 7,609 ads for foods and beverages, or about 1 hour and 15 minutes of messages about fitness or nutrition compared with more than 50 hours of messages promoting food and beverage consumption (Gantz et al., 2007). Across the television landscape, a total of just 17 seconds per hour is donated to PSAs on all topics combined—the equivalent of less than one-half of 1 percent of air time—compared with the 21 percent of air time that is devoted to paid commercial advertising (Gantz et al., 2008).

Evidence

Social marketing is broadly defined as the application of commercial marketing principles to benefit society and the intended audience rather than the marketer. Social marketing applies the techniques of commercial advertising and marketing to the marketing of healthful or prosocial behaviors. Instead of simply providing the consumer with information about public health issues, social marketing often focuses on behavior change, sometimes includes broader environmental and policy goals, and generally uses the insights and avenues of modern product marketing (Grier and Bryant, 2005). For example, the well-regarded “truth” antitobacco youth campaign did not focus on imparting factual information about the health risks of smoking; instead, it focused on fostering a sense of rebellion against corporate tobacco companies, using popular youth media outlets and an edgy youth-oriented visual style to convey its messages and empower the targeted youth. A campaign evaluation concluded that from 1999 to 2002, the “truth” campaign resulted in 300,000 fewer youth smokers (Farrelly et al., 2005).

Because many health-based social marketing campaigns are insufficiently funded, assessing their effectiveness accurately is difficult. However, evidence from carefully designed studies indicates that media campaigns can have a positive impact on health behaviors if they are carefully crafted, well tested, fully funded, highly targeted (in terms of audience and behavior), and sustained over a long period of time (Wakefield et al., 2010).

Social marketing has been used to impact a variety of health and risk behaviors among children, adolescents, and adults. A comprehensive review of mass media campaigns and effects on behavior published by Wakefield et al. (2010) found “strong evidence for benefit” from the majority of antismoking campaigns, and moderate evidence for campaigns to promote physical activity (especially among motivated individuals who received prompts at decision-making moments) and

nutrition (when specific healthy food choices were promoted) (Stead et al., 2007; Wakefield et al., 2010). On the other hand, campaigns to combat drug abuse have had mixed results, and those to reduce alcohol consumption have had little success (Wakefield et al., 2010).

Many health-based social marketing campaigns target parents, who can address the home health environment and talk to their children about specific health behaviors. To initiate health behavior change, many of these campaigns take a multifaceted approach, utilizing community outreach as well as mass media (Evans et al., 2010). One example of a social marketing campaign targeting parents was the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) VERB™ campaign, a well-funded, carefully planned, and highly focused campaign aimed at promoting physical activity among 9- to 13-year-olds (tweens) (Wong et al., 2004). The multi-ethnic campaign was notable for its use of tailored messages aimed at specific audience segments, which included white, black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Asian American tweens (Berkowitz et al., 2008; Huhman et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2004). An evaluation revealed increases in physical activity among important subgroups of youth exposed to the campaign (e.g., 9- to 10-year-olds, girls, children living in urban areas of high density, children from households with annual incomes between $25,000 and $50,000, and children who were low-active at baseline), and also indicated that as tween exposure to the campaign messages increased, more physical activity sessions were reported (a dose-response relationship) (Huhman et al., 2005, 2010). The VERB™ campaign provided evidence that the development of a national media campaign with social marketing messages for young people can help address a significant public health issue such as physical activity (Asbury et al., 2008; Banspach, 2008; Huhman et al., 2010).

In addition to the “truth” campaign referenced above, other youth antismoking campaigns have had an impact on behaviors (Bauer et al., 1999; Biglan et al., 2000; Flynn et al., 1994, 1997; Wakefield et al., 2003). Some of these successful campaigns have included engaging teens and parents in supporting community-level social changes to help prevent adolescent tobacco use (Biglan et al., 2000; Wakefield et al., 2003).

Social marketing also has been found effective in promoting safer sexual behaviors (Zimmerman et al., 2007). One such experiment used extensive formative research to select high-performing ads, targeted a well-defined audience (high-sensation-seeking youth, who were most at risk of unprotected sex), and purchased an extensive inventory of well-targeted air time (Zimmerman et al., 2007). Previous safe sex campaigns not using such techniques generally had yielded modest results.

Implementation

Changing behavior through social marketing campaigns is not easy in the best of circumstances, and most campaigns are waged under less than ideal conditions. Many campaigns are highly underfunded and forced to rely on and settle for infrequent and untargeted donated media time. Often there are few, if any, funds for formative message development and testing, which would allow for the identification of approaches that would garner attention, resonate with the target audience, and be most effective in changing behavior. Adding to these challenges, many social marketing campaigns are not sustained over significant periods of time (Randolph and Viswanath, 2004; Wakefield et al., 2010).

Even when well funded and designed, social marketing programs can be challenging. Most of these campaigns are aimed at behaviors that are difficult to change because of the ubiquitous marketing of foods and beverages that generally are overconsumed according to national dietary guidelines. Further, Cohen (2008) identifies biological (neural) pathways that can lead to food choices that are subconscious, reflexive, or uncontrollable, including responses to food images, cues, and smells and imitation of the eating behaviors of others without awareness of doing so.

To help overcome these challenges, the committee recommends—as is reflected in its recommended potential actions for implementing this strategy—that the proposed new social marketing campaign

• identify a specific set of narrowly targeted audiences;

• focus on a specific set of narrowly defined goals for behavior change among each audience;

• craft tailored messages for each audience;

• sustain each message/audience focus over a period of several years;

• use multiple media platforms, including television, online, print, mobile, and social media platforms;

• enlist support from and develop partnerships with communities, nongovernmental organizations, and for-profit companies to help broaden and sustain the campaign; and

• be sufficiently funded to conduct extensive message-testing research, secure high-quality creative communication experts, and purchase advertising space in media that are highly rated among the target audience, rather than having to rely on donated placements.

A social marketing campaign such as that proposed here can be supported through media advocacy, defined as “strategic use of the mass media to support community organizing to advance a social or public policy initiative.” Media advocacy helps people “understand the importance and reach of news coverage, the need to participate actively in shaping such coverage, and the methods to do so effectively” (Dorfman and Gonzalez, 2011). It is seen as part of a broader strategy of health communication that supports community organizing and policy development and advancement. Additionally, it can support a social marketing campaign’s focus on changing individual health habits by promoting environmental and policy changes required to effect social change (Wallack et al., 1993). This is accomplished by engaging individuals in advocating for larger issues by targeting those in power who can affect these larger community changes (Wallack and Dorfman, 1996). For example, Wallack and Dorfman (2000) describe a local 5-a-Day social marketing campaign with a goal of increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables for pregnant teens in a specific inner-city neighborhood. Before individual behaviors could be expected to change, economic conditions had to change (i.e., the availability and affordability of fruits and vegetables had to be improved). Accomplishing the latter changes involved mobilizing teens to demand the return of grocers, initiate community gardens, and advocate for environmental changes that would make it easier for them and their families to make healthy choices (IOM, 2002).

Basic concepts, tools, planning, and lessons from other media advocacy campaign are detailed elsewhere (Gardner et al., 2010; Wallack and Dorfman, 1996; Wallack et al., 1993), but in this era of reduced resources for journalism, news outlets often lack the resources necessary for the more challenging reporting needed to cover these issues from this broader, societal-level perspective. In addition, it often takes sustained advocacy from health organizations to persuade journalists of the importance of this broader focus. Developing the communication skills of health organizations and supporting journalism education programs can help contribute to a more balanced message environment and promote citizen engagement in the critical policy issues that affect individual behavior change.

Too often, social marketing campaigns are paid lip service by policy makers and expert committees. Ambitious health goals are identified, but the scope and scale of the marketing effort are incommensurate with the goals. A 2006 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report identified 105 PSA campaigns in seven federal agencies from fiscal year (FY) 2003 through the first half of FY 2005 (GAO, 2006). Total funding varied dramatically, including $22,250 for a cam-

paign against human trafficking, approximately $2.3 million for a campaign to promote adoption, $6,400 for a campaign aimed at “all Americans” on aspirin therapy for cardiac health, $550,000 for a long-term care campaign, approximately $184,000 to raise awareness about Head Start in the Hispanic community, and $1,100 for a campaign on the safe use of medicines and supplements during pregnancy (GAO, 2006).

Costs associated with an effective long-term social marketing program will be significant, but represent only a small fraction of the increasing health care costs associated with obesity each year. The use of lower-cost digital media as an important part of the program will help limit expenses and make the program more effective and responsive. However, young people spend much less time with these media than with more expensive outlets, such as television. In 2009, 8- to 18-year-olds spent an average of nearly 4.5 hours a day watching television on a television set, compared with 22 minutes a day using social networking sites (Rideout et al., 2010). To achieve the kind of campaign exposure that will be necessary to effect behavior change, television likely will need to be an important platform.

Indicators for Assessing Progress in Obesity Prevention for Strategy 3-1

Primary Indicators

• Increase in the proportion of children, adolescents, and adults in the target audience meeting the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.*

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

• Increase in the proportion of children, adolescents, and adults in the target audience meeting the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.*

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

Process Indicators

• Successful implementation of a targeted social marketing program.

Sources for measuring indicator: Nielsen (global marketing and advertising research company) and other commercial data

• Documentation of purchases of advertising time and exposure of the target audience to the messages.

Sources for measuring indicator: Nielsen (global marketing and advertising research company) and other commercial data

• Changes in knowledge and attitudes on obesity, physical activity, and nutrition in the target audience from each phase of the campaign.

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

Foundational Indicator

• Provision of funding for the campaign and designation of a lead agency to oversee it.

Sources for measuring indicator: Federal budget and appropriations legislation

![]()

*See Box B-1 in Appendix B.

The food, beverage, restaurant, and media industries should take broad, common, and urgent voluntary action to make substantial improvements in their marketing aimed directly at children and adolescents aged 2-17. All foods and beverages marketed to this age group should support a diet that accords with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans in order to prevent obesity and risk factors associated with chronic disease risk. Children and adolescents should be encouraged to avoid calories from foods that they generally overconsume (e.g., products high in

sugar, fat, and sodium) and to replace them with foods they generally underconsume (e.g., fruits, vegetables, and whole grains).

The standards set for foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents should be widely publicized and easily available to parents and other consumers. They should cover foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents aged 2-17 and should apply to a broad range of marketing and advertising practices, including digital marketing and the use of licensed characters and toy premiums. If such marketing standards have not been adopted within 2 years by a substantial majority of food, beverage, restaurant, and media companies that market foods and beverages to children and adolescents, policy makers at the local, state, and federal levels should consider setting mandatory nutritional standards for marketing to this age group to ensure that such standards are implemented.

Potential actions include

• all food and beverage companies, including chain and quick-service restaurants, adopting and implementing voluntary nutrition standards for foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents;

• the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI) and National Restaurant Association Initiative, as major self-regulatory marketing efforts, adopting common marketing standards for all member companies, and actively recruiting additional members to increase the impact of improved food marketing to children and adolescents;

• media companies adopting nutrition standards for all foods they market to young people; and

• the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regularly tracking the marketing standards adopted by food and beverage companies, restaurants, and media companies.

Context

Children and adolescents are a specific target for food and beverage marketing within societywide message environments including media and packaging. As previously mentioned, food and beverage messaging targeting children and adolescents is much like their diet—mostly high in sugars, fat, sodium, and calories and very low in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and dairy products (Cheyne et al., 2011; Grotto and Zied, 2010; Harris et al., 2010; Harrison and Marske, 2005; IOM, 2006). The media messaging environment surrounding children and adolescents is

ubiquitous and occupies more of their waking time than any other daily activity, including school. Average daily media use by 8- to 18-year-olds is more than 7.5 hours, more than one-fourth of which is spent using multiple media (Rideout et al., 2010). One study estimates that in 2009, 2- to 11-year-olds saw 11-13 television food and beverage-related ads per day (Powell et al., 2011). In another study, Kunkel and colleagues (2009) estimate that children viewing children’s programming saw on average 7.5 food and beverage advertisements per hour. Black children and adolescents view significantly more television than their peers and consequently are exposed to more food and beverage and restaurant advertisements on television—36 percent more food and beverage product advertisements and 21 percent more restaurant advertisements (Harris et al., 2010).

The message environments directly targeting children and adolescents show year-to-year variations in product mix, dollars spent, and media mix in food and beverage marketing. For example, food advertising on television has declined somewhat, while less expensive digital marketing is growing rapidly. Nevertheless, foods marketed to children and adolescents continue to be nutrition poor and high in fat, sugars, and sodium (FTC, 2008; Harris et al., 2010, 2011; IOM, 2006; Powell et al., 2011).

Furthermore, the above estimates regarding foods marketed to children and adolescents generally do not include product placement on television or in digital media (e.g., the Internet, mobile devices). Nontraditional marketing, such as Internet-based advergames featuring brands or product avatars, virtual environments, couponing on cell phones, or stealth marketing on social networks (e.g., an individual child’s 8-minute engagement with a brand or product in an advergame), is not easily measured by dollars spent, and exposure can be difficult to “count” (Chester and Montgomery, 2011; Cheyne et al., 2011). An estimated 85 percent of child-oriented brands from food companies that advertise heavily to children on television also have a website with content for children (Moore and Rideout, 2007). Minority children and adolescents (i.e., Hispanic, Asian, black) are especially attractive market segments for digital media and product placement because, on average, they spend significantly more time using computers and video games than their white counterparts, are increasingly targeted for low-cost and low-nutrition foods and beverages, and have more favorable attitudes toward marketing efforts targeting them (Aaker et al., 2000; Grier and Brumbauch, 1999; Grier and Kumanyika, 2008; Rideout et al., 2011). Chester and Montgomery (2007) describe how the rapid expansion of digital marketing requires the participation of various stakeholders, such as the food and media industries, and suggest that the

paucity of research regarding nontraditional marketing practices warrants a new set of food and beverage regulations encompassing these practices as well as traditional advertising.

In short, there is good evidence that children and adolescents consume too much sugar, fat, and sodium and insufficient amounts of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; that food marketing targeting children and adolescents is heavily for products high in sugar, fat, and sodium; and that marketing is ubiquitous in the message environments of children and adolescents.

Evidence

Marketing—including marketing targeting children and adolescents—works. A systematic review of peer-reviewed research documents evidence of a causal relationship between television advertising and the food and beverage preferences, purchase requests, and short-term consumption of children aged 2-11 (IOM, 2006). Additionally, a body of evidence documents an association of food and beverage television advertising with the adiposity (body fatness) of children and adolescents aged 2-18, although the literature is insufficient to convincingly rule out other explanations (IOM, 2006). Because food marketing reaches children and adolescents regularly through multiple media channels, short-term consumption can become regular consumption. In short, marketing works effectively to cause children to prefer, request, and consume sugary, fatty, and salty foods marketed to them.

Although there is agreement among researchers that children aged 8 and younger do not effectively comprehend the persuasive intent of marketing messages (IOM, 2006), reviews of basic research on adolescent development in the fields of neuroscience, physiology, and marketing find evidence that adolescents (aged 12-17) are more impulsive and self-conscious than adults—unable to resist acting on urges and relying on positive images to gain self-worth (Pechmann et al., 2005). This and other emerging research (Dosenbach et al., 2010; Luna, 2009; Steinberg, 2010) continues to support the protection of adolescents from exposure to advertising and promotions “for high-risk, addictive products, especially if impulsive behaviors or image benefits are depicted” (Pechmann et al., 2005, p. 202).

As a result of these findings, the landmark 2006 IOM report on food marketing to children and youth recommends that “the food, beverage, restaurant and marketing industries should work with government, scientific, public health and consumer groups to establish and enforce the highest standards of marketing of foods, beverages and meals to children and youth” (p. 12). The report also calls on industry to reformulate products to be “substantially lower in fats, salt and

added sugars, and higher in nutrient content” (p. 11). Finally, the report recommends that the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) report to Congress within 2 years on the progress made and additional actions necessary to accelerate progress (IOM, 2006).

Implementation

Some food and beverage companies, including some fast-food restaurants, have taken steps that acknowledge their responsibility to help protect some children and adolescents from marketing of less healthy foods.

Following publication of the 2006 IOM report on food marketing to children and youth, the Council of Better Business Bureaus and the Children’s Advertising Review Unit organized a self-regulatory initiative of 10 major food and beverage companies—CFBAI—to limit their food and beverage marketing (mostly television advertising) to children under age 12 to “better for you” products. The initiative encompasses the use of licensed characters, movie tie-ins, and celebrity use. The television marketing requirements also restrict the use of paid product placements in child-directed programming. In 2008, the FTC presented a report to Congress regarding food marketing to children and adolescents that described significant progress such as the establishment of the CFBAI and outlined necessary future actions for the food and beverage industry and entertainment and media industries (FTC, 2008). In 2010, the CFBAI was extended to include aspects of digital marketing (Kolish, 2011). Definitions of “better for you” were determined individually by each participating company (Peeler et al., 2010). In 2011, the CFBAI reported having 17 member companies representing 79 percent of food, beverage, and restaurant television advertisements and 73 percent of products promoted on children’s televisions programming; the initiative’s representation in media other than television (i.e., radio, the Internet) has not been reported (Kolish, 2011). CFBAI reports have shown nearly total compliance by members with their individual marketing standards; however, compliance in media other than television has not yet been reported (Kolish, 2011).

Independent researchers, using uniform and more stringent nutrition standards of independent authorities such as the HHS “Go-Slow-Whoa” food rating system or recommended school meal standards, have found that since the CFBAI began, most advertisements directly targeting children have continued to be for products high in calories, fats, sugars, and sodium and low in other nutrients under-represented in children’s diets—a reported 72 percent of all food and beverage advertisements for children’s programming and 86 percent of food and beverage

advertisements seen by children (Kraak et al., 2011; Kunkel et al., 2009; Powell et al., 2011). A recent analysis found that exposure to advertisements for “sugary drinks and energy drinks” increased from 2008 to 2010 for preschoolers (4 percent), children (8 percent), and teens (18 percent) (Harris et al., 2011). In addition, a significant proportion—about 25 percent—of television food ads targeting children are by non-CFBAI companies and are for products of poorer nutritional quality than those of CFBAI members (Kunkel et al., 2009). In 2011, the FTC released the voluntary nutrition principles of the federal Interagency Working Group on Food Marketed to Children for foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents aged 2-17 (Interagency Working Group on Food Marketed to Children, 2011). After the proposed principles were published, they were rejected in public comments from the food and beverage industry, the fast-food industry, media companies, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on the grounds of their potential to have a significant economic impact (i.e., job and sales losses) and to lead to interference with companies’ First Amendment rights to free speech (Bachman, 2011; Layton and Eggen, 2011). Additionally, the food and beverage industry claimed that the proposed principles were extremely limiting and could prohibit marketing of healthy foods, an argument that was refuted by researchers analyzing CFBAI-approved products1 (GMA, 2011b; Wootan, 2011).

Furthermore, the public health community is concerned about the potential for overfortification of foods with nutrients that are encouraged by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Unless rules are put in place to prevent it, manufacturers could choose to fortify products to allow them to be marketed to children and adolescents. As summarized in a recent IOM report (2010), overfortification could result in deceptive or misleading claims or could encourage the addition of nutrients to food products in which the nutrient is unstable or biologically unavailable (counter to the Food and Drug Administration’s [FDA’s] fortification policy).

Since the CFBAI began, a number of new food, beverage, and restaurant industry initiatives have been announced, including additional self-regulatory efforts regarding marketing of products to children aged 2-12, as well as product reformulations. Among these initiatives are uniform nutritional standards for marketing in the CFBAI; a new initiative from the National Restaurant Association, which was adopted by 19 large restaurant chains; and a commitment by several major quick-service restaurants and large food manufacturers and distributors regarding nutritional formulation of some child and adult meals and food products (CFBAI, 2011; McDonald’s, 2011; NRA, 2011; Walmart, 2011). The committee welcomes such

![]()

1 Researchers used CFBAI standards as of March 2011.

steps toward reducing marketing of unhealthy foods to some children and adolescents and improving the nutritional quality of some foods intended for children, as well as recognition by several companies and industry associations of the need to protect children from marketing of unhealthy foods.

In sum, changing the current message environments to market healthy foods for children and adolescents and eliminating marketing of foods that could negatively impact their health and weight, thereby reducing their overall exposure to marketing of such foods, will accelerate obesity prevention because of the documented effects of food marketing on this population’s preferences, purchase requests, and consumption. Adoption of uniform guidelines developed around a central goal of healthy dietary patterns and covering all foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents will help all families and their children prefer, request, and consume healthier foods and meals. The recent activity of the food and beverage manufacturing and restaurant industries to this end is welcome and encouraging, but food marketing targeting children and adolescents continues to heavily promote products high in sugar, fat, and sodium. Implementing a common set of guidelines that includes all forms of marketing and extending these guidelines to the age of 17 will accelerate reductions in the consumption of nutrients that are currently overconsumed relative to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and may increase the consumption of nutrients that support a healthy diet and are currently underconsumed. These actions also may help reduce disparities in obesity rates for those youth who have greater exposure to media, including black, Hispanic, and Asian youth.

Indicators for Assessing Progress in Obesity Prevention for Strategy 3-2

Primary Indicator

• Reduction in the proportion of solid fats and added sugars consumed by children aged 2 and older as recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.*

Source for measuring indicator: NHANES

Process Indicators

• Increase in the proportion of companies that adopt marketing standards substantially similar to the committee’s recommendation.

Sources for measuring indicator: CFBAI reports or other trade organization tracking report

• Increase in the market share of products marketed to children and adolescents that are consistent with the marketing standards recommended in this report.

Sources for measuring indicator: CFBAI reports or other trade organization tracking report

• Increase in the proportion of healthy foods marketed to children and adolescents (i.e., as defined by the marketing standards recommended in this report) across all media.

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

• Increase in the proportion of foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents that are recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.*

Source for measuring indicator: NHANES

• Increase in the proportion of food and beverage and media companies that establish common nutritional requirements for foods and beverages marketed to children and adolescents.

Sources for measuring indicator: CFBAI reports or other industry-related tracking reports

Foundational Indicators

• Promulgation by self-regulation or government of marketing standards for children and adolescents substantially similar to the committee’s recommendation.

Sources for measuring indicator: CFBAI reports or other industry-related tracking reports

• Continued monitoring of food marketing to children and adolescents by the FTC.

Source for measuring indicator: FTC follow-up study

• Development of appropriate exposure measures covering digital marketing as well as traditional ads.

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

NOTE: CFBAI = Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative; FTC = Federal Trade Commission; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

![]()

*See Box B-1 in Appendix B.

The FDA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) should implement a standard system of nutrition labeling for the front of packages and retail store shelves that is harmonious with the Nutrition Facts panel, and restaurants should provide calorie labeling on all menus and menu boards.

Potential actions include

• The FDA and USDA adopting a single standard nutrition labeling system for all fronts of packages and retail store shelves, the FDA and USDA considering making this system mandatory to enable consumers to compare products on a standard nutrition profile, and the guidelines provided by the Institute of Medicine (2011a) being used for implementation; and

• restaurants implementing the FDA regulations that require restaurants with 20 or more locations to provide calorie labeling on their menus and menu boards, and the FDA/USDA monitoring industry for compliance with this policy.

Context

Americans may intend to eat more healthfully, but this intention does not necessarily reflect their behavior. Consumer research based on self-reports suggests that 75 percent of adults are actively trying to make healthier choices, but the number reporting certain eating behaviors (e.g., attempts to limit calories, trans fats, or sodium) in accord with those intentions is about 50 percent (FDA, 2008). Nutrition labeling, one marketing technique, is intended to be used as a tool to help consumers to eat healthier diets and meet dietary recommendations.

Consumers generally are unaware of, or inaccurately estimate, the number of calories in restaurant foods (Elbel, 2011). Even if the caloric values of menu items are displayed in restaurants, consumers have difficulty placing this information in context with their total daily caloric intake. Such limitations in comprehension resulting from, for example, displaying calorie values without providing an anchor of recommended meal or daily caloric intake, can limit the effect of the information provided (Roberto et al., 2010).

Additionally, detailed nutrition labeling on prepackaged foods generally is misinterpreted or difficult to understand for consumers (Morestin et al., 2011). Consumers have difficulty interpreting the amount of calories and nutrients that is appropriate for them to consume, and some of the information presented on food packaging can be misleading. The variety of logos and criteria currently being used for nutrient content claims and health claims—about 20 different systems are in use by food manufacturers—is confusing to the consumer (IOM, 2010; Kelly et al., 2009; Lobstein and Davies, 2009; Louie et al., 2008) and sometimes requires interpretation. This situation is counterproductive to the goal of nutrition labeling given that consumers tend to make buying decisions in seconds (Hoyer, 1984) and do not take time to analyze nutritional information that is presented (Higginson et al., 2002; Scott and Worsley, 1997).

Evidence gathered since the introduction of the standardized food label in 1994 on the influence of food labels on purchasing behavior and thereby on nutrient intake and dietary patterns is encouraging but limited (Blitstein and Evans, 2006; Kim et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2004; Neuhouser et al., 1999; Ollberding et al., 2010; Satia et al., 2005). Nonetheless, it is known that significant disparities exist in the use of food labels across many demographic characteristics. Disparities have consistently been found by sex, education, income, language, length of residency in the United States for those foreign born, and race (Bender and Derby, 1992; Blitstein and Evans, 2006; Guthrie et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2004; Nayga, 2000; Neuhouser et al., 1999; Ollberding et al., 2010; Satia et al., 2005).

Despite the potential of food and menu labeling to encourage healthier food purchases and dietary patterns, the consistently low rates of label use, especially among particular populations that also are disproportionately at risk of overweight and obesity, suggest it may be necessary to modify existing food labels or restaurant labeling to achieve a greater impact on the population. A standard system for fronts of packages, retail shelving, and menu labeling at restaurants would help simplify consumers’ choices and enable them to have more information when they make these choices outside the home.

Evidence

Restaurant menu labeling Prior expert committees have made recommendations similar to those offered here for posting calorie content on menus and menu boards (IOM, 2005, 2006, 2009; Keystone Forum, 2006; Lee et al., 2008; RWJF, 2009). These recommendations are supported by the fact that consumers overestimate the healthfulness of restaurant items, and recent research has shown that calorie and nutrition information provided at the point of purchase may influence their food choices, even prompting them to purchase menu items that lower their overall caloric intake. Indeed, a number of localities have begun to institute such menu labeling policies (IOM, 2009; Morrison et al., 2011; RWJF, 2009).

Front-of-package nutrition labeling Front-of-package labeling is designed to help customers identify products that support healthy diets for themselves and their families by providing useful information at the point of purchase (IOM, 2010). An IOM committee recommended implementing a common front-of-package labeling system on prepackaged foods in 2005, and this recommendation was reinforced by another IOM committee in 2010 (IOM, 2005, 2010; White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity, 2010).

Nationally, a number of front-of-package systems currently are being used on prepackaged foods, and there has been some preliminary evaluation of their impact. Compared with detailed nutrition labeling, more positive evidence has been gathered on the impact of front-of-package labeling on consumer comprehension and healthier food purchases, although some of the evidence in this regard is mixed (Larsson et al., 1999; Morestin et al., 2011; Sacks et al., 2011; Sutherland et al., 2010). A recent review concluded that consumers are able to understand certain front-of-package logos quickly and use them to correctly differentiate healthy and less healthy foods (Borgmeier and Westenhoefer, 2009; Feunekes et al., 2008; Grunert and Wills, 2007; Kelly et al., 2009).

Effects on product reformulation Nutrition labeling has been hypothesized and observed to have an effect on the manufacturing of food (Morestin et al., 2011). Researchers have proposed that displaying the nutritional value on a food product can raise awareness of its nutritional quality and lead to increased consumer demand for healthier products, thus motivating manufacturers to make their products healthier. A recent review cites numerous studies finding that nutrition labeling (including front-of-package systems and menu labeling in restaurants) has motivated food producers and restaurants to make healthier products (Morestin et al., 2011). Additionally, it has been observed that the reformulation of food products benefits all consumers, not just those who use nutritional information to influence their purchases, because it automatically improves the nutritional value of products in the food supply (Golan et al., 2007). For example, a federal trans fat labeling requirement led to a dramatic increase in products claiming “no trans fat” (Golan et al., 2007; Morrison et al., 2011) and a 50 percent reduction in partially hydrogenated oils in foods in North America (Watkins, 2008). Similarly, when the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommended that half of the grains people consume be whole grains, the number of new whole-grain products dramatically increased. This dramatic increase in whole grains in the food supply resulted in an increase in sales of healthier foods containing these grains (Morrison et al., 2011).

Implementation

Nutrition labeling in restaurants with 20 or more locations is set to be implemented through FDA regulations (preempting state and local policies), providing calorie information on standard menu items in certain chain restaurants and similar retail food establishments (FDA, 2011). These provisions also include posting a statement describing the recommended daily caloric intake as an anchor for the posted calorie information. These requirements may encourage other restaurants not already covered by the regulations to take similar actions (FDA, 2011).

Detailed labeling of prepackaged foods, meat, poultry, and egg products, including nutrition information and the ingredients list, is required by regulations of the FDA and USDA. Additionally, food packages must include the Nutrition Facts panel and can include nutrient content claims (e.g., “low fat”) and health claims to characterize the food’s relationship to a disease or health condition (e.g., “may reduce the risk of heart disease”) (FDA, 2009). Two IOM reports (2010, 2011a) provide insight on how front-of-package systems should be used as a tool in the future, their target audience, nutrient information that would be most use-

ful to include, and criteria that would be useful in determining which systems and symbols are most helpful.

Internationally, some steps have been taken toward developing national guidance for a front-of-package labeling system, including use of the keyhole symbol and the “traffic-light” system (National Food Administration, 2011; NHS, 2011). Both of these systems are voluntary. In January 2011, leading food and beverage manufacturers and retailers launched a voluntary front-of-package labeling system to help consumers make informed choices in the United States (GMA, 2011a). This Facts Up Front system adheres to current FDA nutrition labeling regulations and guidelines and provides information about calories and three nutrients to limit (saturated fats, sodium, and sugars); there is also an option to include up to two nutrients to encourage (e.g., fiber, potassium). This labeling system was intended to complement the American Beverage Association’s “Clear on Calories” labeling system, launched in February 2011, whereby all beverages 20 ounces in size or smaller will be labeled with the total calories per container on the front of the package (ABA, 2011). Because implementation of the Facts Up Front labeling system has only just begun, its effect on consumer choice is unknown; however, researchers have begun to question the science base for and the possibly confusing nature of the consumer approach taken with this system (Brownell and Koplan, 2011).

Finally, a number of food manufacturers and restaurants have already begun to reformulate products, reduce portion sizes, or use more healthy ingredients (Bernstein, 2011; Rogers, 2011; Walmart, 2011). Although forthcoming federal nutrition labeling regulations have not always been directly cited as the impetus for such actions, others have hypothesized that they are having this effect (Golan et al., 2007; Morrison et al., 2011).

In sum, given the proliferation of front-of-package labeling systems and logos for prepackaged foods and restaurant menu labeling policies, a common labeling system in stores and restaurants that can be easily understood by the general population will help optimize opportunities for children, adolescents, parents, and other adults to identify and encourage purchases of healthier foods. Although a number of menu labeling policies have been introduced and implemented over the past decade, a majority of the population is not impacted by these policies. Additionally, although recent actions of the food and beverage industry are encouraging, the recently developed voluntary front-of-package system may not be easily understood by all consumers or maximize the opportunity for them to make healthier food choices. Implementing a common system for prepackaged foods and restaurant menu labels could also continue to move the industry to

reformulate or repackage foods, thereby altering the food supply and encouraging consumers to purchase healthier foods. This recommendation may have the added benefit of reducing disparities in obesity rates for consumers who are less likely to use the more detailed (existing) label on prepackaged foods and are at an increased risk of obesity, including individuals with lower education and income levels, racial and ethnic minority groups, and those with limited English language proficiency.

Indicators for Assessing Progress in Obesity Prevention for Strategy 3-3

Process Indicators

• Increase in the percentage of food manufacturers that voluntarily agree to market only healthy foods to children and adolescents.

Sources for measuring indicator: Government, trade, and advocate organizations

• Increase in the proportion of restaurants with 20 or more locations that meet the menu and menu board calorie labeling regulations.

Sources for measuring indicator: Government, trade, and advocate organizations

• Increase in the proportion of consumers who purchase and consume foods recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.*

Sources for measuring indicator: BRFSS and YRBSS

• Increase in the number of new products that help children, adolescents, and adults meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Sources needed for measurement of indicator, such as follow-up reports from government and academics, corporate social responsibility reports by food manufacturers.

• Increase in purchases of reformulated foods that meet the definition in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans of foods people should consume in greater quantities.

Source for measuring indicator: Nielsen Home scan data

Foundational Indicator

• Adoption of federal and legislative policies regarding development of a standard front-of-package and shelf labeling system.

Source for measuring indicator: IOM 2011 report, Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols: Promoting Healthier Choices

NOTE: BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; IOM = Institute of Medicine; YRBSS = Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System.

![]()

*See Box B-1 in Appendix B.

USDA should update the policies for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) and the policies for other federal programs with nutrition education components to explicitly encourage the provision of advice about types of foods to reduce in the diet, consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Potential actions include

• removing the restrictions on the types of information that can be included in SNAP-Ed programs and encouraging advice about types of foods to reduce;

• disseminating, immediately and effectively, notification of the revised regulations, along with authoritative guidance on how to align federally funded nutrition education programs with the Dietary Guidelines; and

• ensuring that such full alignment of nutrition education with the Dietary Guidelines applies to all federal programs with a nutrition education component, particularly programs that target primary food shoppers in low-

income families (e.g., the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC]).

Context

This strategy leverages the extensive reach of the largest federally funded nutrition assistance program, SNAP, to address disparities in obesity. When specific recommendations to accelerate progress in obesity prevention are being considered, including strategies involving SNAP is essential in light of the scale, reach, and federal dollar investment of this program. The committee viewed the context for making SNAP-related recommendations as particularly complex given the program’s reach to a large segment of the low-income population, the potentially far-reaching effects of any changes to the program, and an ongoing public debate concerning ethical and practical questions about strategies that will be most fair and effective (Barnhill, 2011; Brownell and Ludwig, 2011; Hartline-Grafton et al., 2011; Shenkin and Jacobson, 2010). The committee considered various options, including extant proposals for restrictions on purchases of sugar-sweetened beverages and incentives for purchases of healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables.

Viewed in its historical and nutrition policy context as a food security program operating as a cash transfer to low-income families, the overarching aim of SNAP has been and continues to be to ensure that low-income households have enough food to eat based on a market basket of foods determined to meet nutrient needs and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Over time, as evidence has accumulated about the role of diet in chronic disease development, interest in the quality of foods allowable for purchase with SNAP benefits has increased. This interest was reflected in the renaming of the program (from the Food Stamp Program) in 2008 (USDA/FNS, 2011b). Nutritional goals other than the ability to afford an adequate diet are not explicit in the SNAP regulations, which permit purchases of a wide range of foods (USDA, 2011c). In contrast, the WIC has always targeted pregnant and lactating women and infants and children up to age 5, and participants may use its financial assistance to purchase only pre-approved food items that have been deemed most nutritionally beneficial.2

SNAP targets low-income populations in which poorer dietary quality and higher-than-average risks of diet-related diseases are observed relative to higher-income groups (IOM, 2011b). Theoretically, specific strategies to promote healthful food choices among SNAP participants—such as incentives for healthy food

![]()

2 These pre-approved food items make up a portion of the diet, but do not comprise a complete diet.

purchases and restrictions on the types of foods and beverages permissible for purchase with SNAP benefits—could help address these disparities. Sugar-sweetened beverages have been the most widely discussed products to target for restrictions as a way of both reducing their consumption and freeing SNAP dollars for purchases of products that contribute to a nutritionally adequate diet.

Advocates of restricting sugar-sweetened beverage purchases with SNAP benefits argue that they deteriorate diet quality and promote chronic disease (see Chapter 6, Strategy 2-1), with the costs of treating such diseases falling primarily to taxpayers (Brownell and Ludwig, 2011; Shenkin and Jacobson, 2010). In addition, members of the SNAP-eligible population are heavily targeted by sugar-sweetened beverage marketers (Grier and Kumanyika, 2008), and a USDA study found that SNAP participants were more likely than higher-income (ineligible for SNAP) nonparticipants to consume regular (nondiet) soda (Cole and Fox, 2008). Market-oriented arguments also are advanced to support restrictions on foods eligible for SNAP purchases (Alston et al., 2009). For example, SNAP benefit expenditures totaled approximately $50.4 billion in 2009 (the 2011 figure is $71.8 billion) (USDA, 2011d), and because 84 percent of total benefits in 2009 were redeemed in supermarkets/supercenters (USDA/FNS, 2011a), changes to SNAP regulations could provide an indirect stimulus for changes in the behavior of the retail food industry in terms of what products are stocked and promoted (Alston et al., 2009).

On the other hand, restrictions raise both practical and economic concerns. Practical concerns relate to implementation and program administration. Current implementation approaches for SNAP heavily prioritize a transactional process that encourages (or at least does not discourage) program participation through ease of use at the point of purchase and the absence of stigma, and is relatively easy to implement at the retail level. Arguments against restriction include that it may be difficult for policy makers, food retailers, and SNAP participants to distinguish which products are eligible for purchase with SNAP dollars, and purchasing restrictions could cause stigma and confusion at checkout counters, potentially decreasing SNAP participation (Barnhill, 2011; Cook, 2011; Hartline-Grafton et al., 2011; USDA, 2007). Economic analysts raise cautions about the difficulty of estimating with certainty the health or economic outcomes that would result from various perturbations of such a complex system. Simulations of possible effects require multiple assumptions about how both SNAP participants and the retail food market would react—for example, respectively, the types of trade-offs SNAP

participants would make with respect to use of their other sources of income, and effects on demand curves and supplies for certain products (Alston et al., 2009).

Restrictions also raise ethical and social justice concerns related to potential infringement on freedom of choice of SNAP participants. From this perspective, limiting food choices for SNAP recipients may be viewed as patronizing and discriminatory to low-income consumers (Barnhill, 2011; Hartline-Grafton et al., 2011; USDA, 2007). It is also expected that efforts to reform SNAP purchasing regulations would be difficult, given the strong bipartisan support for the program as currently formulated and the strong opposition to restrictive changes from those interested in protecting the role of SNAP in addressing potential hunger and food insecurity for all people at risk.

Support for testing an alternative SNAP reform strategy—providing incentives for healthy food choices—has been more forthcoming than support for trials of restrictions. In August 2011, USDA rejected New York City’s request to pilot a program that would have restricted the purchase of selected sugar-sweetened beverages with SNAP dollars (USDA, 2011a), and requests from other states to implement similar pilot programs have not been approved. USDA is currently testing an incentive strategy for its effects on the purchasing behaviors and diet quality of SNAP participants. The 2008 Farm Bill authorized $20 million to pilot test and rigorously evaluate the impact on the diet quality of SNAP participants of financial incentives at the point of sale for the purchase of fruits, vegetables, or other healthful foods. This Healthy Incentives pilot will run for 15 months during 2011-2013, with key outcomes of interest including changes in the amount of fruits and vegetables consumed and whether additional calories consumed from fruits and vegetables displace calories consumed from other food groups. Several smaller-scale programs incentivizing the purchase of fruits and vegetables are under way in localities such as New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia (Food Fit Philly, 2011; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2010; The Food Project, 2011).

Given the current absence of firm evidence to indicate which, if either, approach to reform of SNAP regulations related to food purchases—restrictions or incentives—would meet standards for feasibility, equity, and impact, the committee identified strategies to improve the marketing and information environment in which SNAP participants purchase foods as an important and viable mechanism with predictable positive effects in accelerating obesity prevention. The USDA Food and Nutrition Service encourages states to provide nutrition education to SNAP participants and eligibles as part of their program operations. The objec-

tive is to provide clear and effective messages for SNAP participants and eligibles about how to make healthy food choices within a limited budget and prevent excess weight gain.

However, current regulations for the SNAP education component (SNAP-Ed) are ambiguous and restrictive in a way that deprives SNAP participants of clear nutrition education, exacerbating existing disparities and undermining the SNAP goals related to overall dietary quality. Although the regulatory language indicates that states should ensure that all nutrition messages conveyed as a part of SNAP-Ed are consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, it also stipulates that “SNAP-Ed funds may not be used to convey negative written, visual, or verbal expressions about any specific foods, beverages, or commodities. This includes messages of belittlement or derogation of such items, as well as any suggestion that such foods, beverages, or commodities should never be consumed” (USDA, 2011b, p. 18). An appendix to the SNAP-Ed guidance (USDA, 2011b, p. 72) states that nutrition education messages and social marketing campaigns that convey negative messages or disparage specific foods, beverages, or commodities are not allowed. Yet “foods to reduce” are the subject of an entire chapter in the Dietary Guidelines (Chapter 3), along with the chapter devoted to “foods to increase” (Chapter 4). In effect, SNAP participants are allowed to receive only half the message. SNAP regulations place few constraints on the types of foods that can be purchased with program benefits (USDA, 2011c), and this flexibility is inconsistent with the constraints on the content of nutrition guidance that can be provided in SNAP-Ed programs. For example, Shenkin and Jacobson (2010) report that according to the federal guidance, health agencies and organizations in four states were required to stop using SNAP-Ed funds to discourage soft drink consumption.

While motivated SNAP-Ed providers may identify ways to work around this limitation, clarification of USDA regulations is required to address this apparent policy conflict. Addressing this problem in ways that explicitly reduced the purchase and consumption of foods identified in the Dietary Guidelines as conducive to obesity and chronic disease development could stimulate the purchase of healthier foods among SNAP participants, who numbered more than 40.3 million in 2010, corresponding to $64.7 billion in benefits for that year (USDA, 2011d). While this strategy refers primarily to SNAP-Ed, it has implications for ensuring that other federal nutrition programs with a nutrition education component (e.g., the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program [EFNEP] and WIC) convey the full scope of advice in the Dietary Guidelines.

Evidence

SNAP, and therefore SNAP-Ed, have extensive reach to populations at a higher-than-average risk of obesity. Eligibility for SNAP requires a family income that is at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty level (Leftin et al., 2010). At some point in their lives, about half of adults (between the ages of 20 and 65) and children in the American population participate in SNAP (Rank and Hirschl, 2003). Approximately half of participants are children, and about a third of participating households are single-adult households with children (VerPloeg and Ralston, 2008).

In absolute numbers, most U.S. adults and children who are obese are in the middle- or high-income range. Relative to adults with higher incomes, however, the prevalence of obesity is higher among low-income women and lower-income children of both sexes (Ogden et al., 2010a,b). In addition, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic adults have higher obesity prevalence than non-Hispanic whites of the same ages (Flegal et al., 2010), and a greater percentage of these populations were below the poverty level in 2009 (25.8 percent of blacks and 25.3 percent of Hispanics, compared with 12.3 percent of whites) (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2010).

Some studies have suggested a positive relationship between SNAP participation and obesity among women. Based on an extensive review by Ver Ploeg and Ralston (2008), some evidence suggests that long-term SNAP participation may contribute to weight gain in women. Nevertheless, the nature of the available data and the differences between characteristics of SNAP participants and income-eligible as well as other nonparticipants make it difficult to confirm a causal relationship (Ver Ploeg and Ralston, 2008). For example, Ver Ploeg and colleagues (2007) report that black women who participated in SNAP had weight levels similar to those of income-eligible black women who did not participate in the program (Ver Ploeg et al., 2007). Food insecurity also has been linked to overweight and obesity in women (Adams et al., 2003; Basiotis and Lino, 2003; Jilcott et al., 2011; Olson, 1999; Townsend et al., 2001). This is important to note given that SNAP was designed to address food insecurity, and SNAP participants are more likely than nonparticipants to experience food insecurity (Cohen et al., 1999; Jensen, 2002; Wilde and Nord, 2005). In other words, as discussed at a 2010 IOM workshop on food insecurity and obesity, it becomes difficult to infer a causal relationship between SNAP participation and obesity because of the many other variables that can influence the likelihood of obesity (IOM, 2011b).

Whether the association between being overweight and the characteristics of those who participate in SNAP is causal or coincidental, this association justifies

an intensified focus on providing guidance to SNAP participants about prevention of excess weight gain. This justification is supported by evidence based on comparisons of the dietary intake of adult SNAP participants with that of income-eligible nonparticipants and higher-income individuals in national survey data. Diets of adult SNAP participants are comparable to those of the other two groups with respect to nutrient adequacy, but contain higher amounts of calories from solid fats and added sugars and reflect a greater frequency of consuming foods recommended for only occasional consumption (Cole and Fox, 2008).