Health Care and Work Environments

Health Care and Work Environments: Goal, Recommendation, Strategies, and Actions for Implementation

Goal: Expand the role of health care providers, insurers, and employers in obesity prevention.

Recommendation 4: Health care and health service providers, employers, and insurers should increase the support structure for achieving better population health and obesity prevention.

Strategy 4-1: Provide standardized care and advocate for healthy community environments. All health care providers should adopt standards of practice (evidence-based or consensus guidelines) for prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of overweight and obesity to help children, adolescents, and adults achieve and maintain a healthy weight, avoid obesity-related complications, and reduce the psychosocial consequences of obesity. Health care providers also should advocate, on behalf of their patients, for improved physical activity and diet opportunities in their patients’ communities.

Potential actions include

• health care providers’ standards of practice including routine screening of body mass index (BMI), counseling, and behavioral interventions for children, adolescents, and adults to improve physical activity behaviors and dietary choices;

• medical schools, nursing schools, physician assistant schools, and other relevant health professional training programs (including continuing education programs), including instruction in prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of overweight and obesity in children, adolescents, and adults; and

• health care providers serving as role models for their patients and providing leadership for obesity prevention efforts in their communities by advocating for institutional (e.g., child care, school, and worksite), community, and state-level strategies that can improve physical activity and nutrition resources for their patients and their communities.

Strategy 4-2: Ensure coverage of, access to, and incentives for routine obesity prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Insurers (both public and private) should ensure that health insurance coverage and access provisions address obesity prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

Potential actions include

• insurers, including self-insured organizations and employers, considering the inclusion of incentives in individual and family health plans for maintaining healthy lifestyles;

• insurers considering (1) benefit designs and programs that promote obesity screening and prevention and (2) innovative approaches to reimbursing for routine screening and obesity prevention services (including preconception counseling) in clinical practice and for monitoring the performance of these services in relation to obesity prevention; and

• insurers taking full advantage of obesity-related provisions in health care reform legislation.

Strategy 4-3: Encourage active living and healthy eating at work. Worksites should create, or expand, healthy environments by establishing, implementing, and monitoring policy initiatives that support wellness.

Potential actions include

• public and private employers promoting healthy eating and active living in the worksite in their own institutional policies and practices by, for example, increasing opportunities for physical activity as part of a wellness/health promotion program, providing access to and promotion of healthful foods and beverages, and offering health benefits that provide employees and their dependents coverage for obesity-related services and programs; and

• health care organizations and providers serving as models for the incorporation of healthy eating and active living into worksite practices and programs.

Strategy 4-4: Encourage healthy weight gain during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and promote breastfeeding-friendly environments. Health service providers and employers should adopt, implement, and monitor policies that support healthy weight gain during pregnancy and the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Population disparities in breastfeeding should be specifically addressed at the federal, state, and local levels to remove barriers and promote targeted increases in breastfeeding initiation and continuation.

Potential actions include

• all those who provide health care or related services to women of childbearing age offering preconception counseling on the importance of conceiving at a healthy BMI;

• medical facilities, prenatal services, and community clinics adopting policies consistent with the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative;

• local health departments and community-based organizations, working with other segments of the health sector, providing information on breastfeeding

and the availability of related classes to pregnant women and new mothers, connecting pregnant women and new mothers with breastfeeding support programs to help them make informed infant feeding decisions, and developing peer support programs that empower pregnant women and mothers to obtain the help and support they need from other mothers who have breastfed;

• workplaces instituting policies to support breastfeeding mothers, including ensuring both private space and adequate break time; and

• the federal government using Prevention Fund dollars to support implementation of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative nationwide, and providing funding to support community-level collaborative efforts and peer counseling with the aim of increasing the duration of breastfeeding.

Millions of individuals have the opportunity to be influenced by health care and work environments daily:

• More than 140 million American civilians were employed as of November 2011 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011).

• In 2008, it was estimated that there were more than 6.2 million professionals in health care occupations (including physicians, registered dietitians, nurses, and counselors) in the United States. The field is projected to increase by 22 percent by 2018 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010).

• As of June 2011, among Americans under age 65, nearly 23 percent were covered by a public health insurance plan, and 61 percent had private health insurance coverage (Martinez and Cohen, 2011).

• For 2011, the total number of Medicare beneficiaries in the United States was 48 million (KFF, 2011).

It is clear that health systems, health care providers, employers, and insurers are in a position to influence the health of the population. By engaging in obesity prevention and treatment strategies, such as providing community-level resources (education, support, and opportunities) for individuals and their families, health care and work environments can help catalyze individual and, ultimately, popu-

lation health improvement. For example, as seen with smoking, another public health concern, cessation initiatives by insurance and health care providers that supported and encouraged policy holders and patients to quit, as well as workplace interventions that included counseling or support, had a noticeable effect on quitting rates (Cahill et al., 2008; CDC, 2011c).

As health care continues to evolve and as new forms of health systems emerge (such as patient-centered medical homes, accountable care organizations, and other new systems of care), attention to obesity prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment must be considered.1

Health care and health service providers, employers, and insurers should increase the support structure for achieving better population health and obesity prevention.

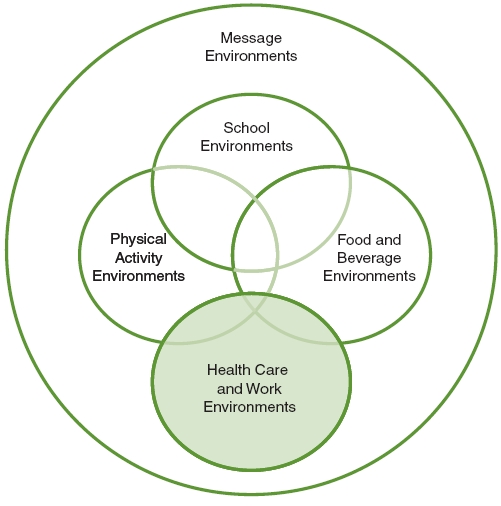

As depicted in Figure 8-1, health care and work environments are interconnected with the other four areas of focus addressed in this report and are a necessary component of the committee’s comprehensive approach to accelerating progress in obesity prevention.

The committee’s recommendations for strategies and actions to expand the role of health care and health service providers, employers, and insurers in obesity prevention are detailed in the remainder of this chapter. Indicators for measuring progress toward the implementation of each strategy, organized according to the scheme presented in Chapter 3 (primary, process, foundational) are presented in a box following the discussion of that strategy.

STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

Strategy 4-1: Provide Standardized Care and Advocate for Healthy Community Environments

All health care providers should adopt standards of practice (evidence-based or consensus guidelines) for prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of overweight and obesity to help children, adolescents, and adults achieve and maintain a healthy weight, avoid obesity-related complications, and reduce the

![]()

1 Attention to overweight prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment is implicit within obesity prevention and treatment efforts.

FIGURE 8-1 Five areas of focus of the Committee on Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention.

NOTE: The area addressed in this chapter is highlighted.

psychosocial consequences of obesity. Health care providers also should advocate, on behalf of their patients, for improved physical activity and diet opportunities in their patients’ communities.

Potential actions include

• health care providers’ standards of practice including routine screening of body mass index (BMI), counseling, and behavioral interventions for children, adolescents, and adults to improve physical activity behaviors and dietary choices;

• medical schools, nursing schools, physician assistant schools, and other relevant health professional training programs (including continuing education programs), including instruction in prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of overweight and obesity in children, adolescents, and adults; and

• health care providers serving as role models for their patients and providing leadership for obesity prevention efforts in their communities by advocating for institutional (e.g., child care, school, and worksite), community, and state-level strategies that can improve physical activity and nutrition resources for their patients and their communities.

Context

Health care and health service providers have frequent opportunities to engage in screening for disease risk factors and to encourage their patients to engage in healthful lifestyles. The current health care system has an opportunity to incorporate obesity and lifestyle screening and prevention into routine practice as it has done with colon cancer, breast cancer, cervical cancer, and cardiovascular disease, for example. Health care professionals, both individually and through their professional organizations, can work to make obesity prevention part of routine preventive care.

To maximize the value of patient visits and help children, adolescents, and adults achieve and maintain a healthful lifestyle, health care providers should adopt standards of practice for the prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of obesity that include screening of BMI, counseling, and behavioral interventions aimed at improving the physical activity and dietary behaviors of their patients.

Standards of practice, or clinical practice guidelines, are statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options (IOM, 2011a). Such guidelines offer an evaluation of the quality of the relevant scientific literature and an assessment of the likely benefits and harms of particular interventions or treatments (IOM, 2011a). This information enables health care providers to proceed accordingly, selecting the best care for an individual patient based on his or her preferences. Health care providers have the opportunity to see children and adolescents, in particular, at regular and frequent intervals for well and acute care, and they are in a unique position to promote childhood obesity prevention in several ways.

Evidence

In 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended the use of age- and sex-adjusted BMI to screen for overweight children 2-19 years of age and developed revised standardized growth charts (Kuczmarski et al., 2002). In 2003, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that health care providers calculate and plot BMI percentiles on a yearly basis for children and adolescents (Krebs and Jacobson, 2003). More recently, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee that produced the report Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies recommended that health care professionals consider a child’s BMI, rate of weight gain, and parental weight as risk factors for obesity (IOM, 2011b).

If health care providers monitor the rate of weight gain using BMI, they are more likely to identify children who are at risk for overweight or obesity earlier than if they use traditional methods for plotting weight for age (Sesselberg et al., 2010; Wethington et al., 2011). Yet even though most health care providers report being familiar with BMI screening guidelines and have the tools to calculate patient BMIs, few providers report actually using BMI to assess overweight or obesity (Barlow et al., 2002; Hillman et al., 2009; Larsen et al., 2006; Wethington et al., 2011). Indeed, many health care providers are not properly diagnosing obesity (Dennison et al., 2009; Hamilton et al., 2003; Perrin et al., 2010). Some providers report not having enough time during patient visits for overweight screening (Boyle et al., 2009; Hopkins et al., 2011), and others report lack of reimbursement and inadequate resources (i.e., staff and/or access to nutrition specialists) as barriers to BMI screening, obesity diagnosis, and counseling on weight/health status (Barlow et al., 2002; Hopkins et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2006). Clinicians who document overweight in the patient medical record are more likely to screen for BMI, provide counseling, and make referrals to specialists (Sesselberg et al., 2010; Wethington et al., 2011).

The United States is currently undergoing a transition to more universal and higher utilization of electronic health records (EHRs). This transition is the result of a recent government effort (through the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health [HITECH] Act) to support the adoption and “meaningful use” (meaning use intended to improve health and health care) of EHRs and health information technology (Blumenthal, 2011). Accelerated adoption of EHRs might facilitate the adoption of standards of practice that include BMI screening, assessment, and tracking, and would allow for the capture of quality improvement efforts and measures. Use of EHRs has been shown to signif-

icantly increase BMI assessment and documentation and treatment of obese adults among family physicians (Sesselberg et al., 2010).

Use of EHRs would allow BMI and BMI percentiles (which are important measures, particularly for children and pregnant women, because ideal weights vary by age) to be calculated automatically when patient vital signs are obtained. In addition, EHRs can incorporate decision-support tools that could provide prompts for brief motivational interviews, links to food and activity resources, or facilitated referrals to specialists. If EHR vendors included data fields to capture pediatric and adult BMI, document nutrition and activity counseling, and identify resources on healthy lifestyles for physicians and patients, they would facilitate the delivery of individual care, as well as allow for better population health management at the practice level and surveillance and monitoring of public health data at the community, local government, and state levels. Practice-level data could be fed into health information exchanges (HIEs), a system of aggregated health care information available electronically across organizations within a community, region, or hospital system. HIEs would allow for community-based, as well as clinically based, interventions by allowing public health and medical care providers to fully utilize decision support and resources.

Including BMI screening as part of routine visits would give health care providers a platform through which they could engage patients (and their families) on the health benefits of a healthy weight and lifestyle and the health consequences of overweight and obesity (including elevating parental concern about childhood obesity if a patient was at risk) (IOM, 2005). In addition to monitoring and tracking of BMI, other predictors of risk for obesity should be added to risk assessment, including birth weight and parental BMI (for pediatric patients) and maternal gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes, and smoking status (for adult patients) (Flegal et al., 1995; IOM, 2009b; Whitaker et al., 1997). If health care providers addressed risks for overweight and obesity, families would receive the full benefit of counseling and early intervention.

Although it is recommended that clinicians offer counseling and behavioral support to obese patients, however, studies have found that many health care providers do not feel prepared, competent, or comfortable in discussing weight with their patients and lack reliable models of treatment to guide their efforts (Appel et al., 2011; Hopkins et al., 2011). Few report offering specific guidance on physical activity, diet, or weight control, even though clinical preventive visits that include obesity-related discussions have been shown to increase levels of physical activity among sedentary patients (Calfas et al., 1996; Sesselberg et al., 2010; Smith et al.,

2011). Moreover, disparities are seen in which patients actually receive screening and counseling. A recent study of more than 9,000 adolescents, for example, found that overweight teens are receiving less screening and fewer preventive measures than normal-weight and obese patients during routine checkups (Jasik et al., 2011). This finding calls for accelerating educational and quality improvement efforts aimed at incorporating obesity care into practice.

In addition to BMI screening, the use of physical activity as a vital sign is considered a promising way to increase the frequency with which health care providers counsel patients about physical activity. It has been found to be a valid clinical screening tool (Greenwood et al., 2010), although more evidence is needed to determine whether it correlates with improved BMI and/or health status. To measure physical activity as a vital sign, health care providers could ask adult patients simple questions about days per week of physical activity and the intensity of that activity. Parents and their children also could be asked questions about how much time they spend in physical activity or physical education in school and how much time they spend outdoors. Because responses to such questions about typical behavior have been found to be highly correlated with BMI (Greenwood et al., 2010), they would provide an opportunity for health care providers to discuss physical activity with their patients.

Many health care providers are already focused on helping patients adopt healthy lifestyle behaviors, but a significant gap remains between current practice and universal and consistent lifestyle counseling (Huang et al., 2011). Increased education for health care providers, both during initial schooling/training and as part of continuing education, on how to incorporate BMI screening (measuring and assessment) and effective counseling and behavioral interventions into patient visits could lead to broader use of these practices (Klein et al., 2010). For example, training focused on human nutrition would allow a health care provider to counsel effectively on nutrition, while training in behavior change counseling could help a health care provider motivate a patient to make lifestyle changes. In fact, a recent study found that physician participation in a learning collaborative increased the number of primary care practices that provided anticipatory guidance on obesity prevention and that identified and treated overweight or obese children (Young et al., 2010).

By maintaining a healthy weight and lifestyle of their own, health care providers also have an opportunity to influence their patients. Studies suggest that providers’ own weight, eating habits, and physical activity levels may influence how they approach these subjects with their patients (Hopkins et al., 2011).

Studies also have shown that physicians who engage in physical activity are more likely to counsel patients on the benefits of exercise (Abramson et al., 2000). Confidence scores from patients receiving health counseling from obese physicians are consistently lower than those from patients seeing normal-weight physicians (Hash et al., 2003).

Outside of their offices, health care providers can use their influence and authority to inform policy at the local, state, and national levels by advocating for health improvement and obesity prevention. Health care providers can be powerful advocates for obesity-preventing environmental and policy change in their communities. More than 90 percent of U.S. physicians surveyed supported physician participation in public roles defined as “community participation and individual and collective health advocacy” (Gruen et al., 2006, p. 2,473). Involvement in issues closely related to individual patients’ health was rated as very important (Gruen et al., 2006). By engaging in advocacy, health care providers can play a pivotal role in incorporating knowledge of individual factors that promote or inhibit healthy lifestyle change into a wider community perspective.

Implementation

Recent surveys have found that approximately 44 percent of U.S. hospitals and nearly half of outpatient practices are employing EHRs (Classen and Bates, 2011). The challenge now is how to ensure meaningful use of EHRs for patient care, as data have suggested that simply using EHRs does not necessarily result in improved quality of care provided, even over time (Classen and Bates, 2011).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that children and adolescents be screened for obesity and that clinicians offer or make referrals for “comprehensive, intensive behavioral interventions to promote improvement in weight status” (USPSTF, 2010a, p. 362). These recommendations for children, adolescents, and adults also have been included in a list of preventive services to be provided with no copay under the federal health care reform legislation signed into law in March 2010 (USPSTF, 2010b). The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) has stated that family physicians should offer assistance to patients who are obese or overweight or who request assistance in preventing obesity (Lyznicki et al., 2001). Health care professional organizations and provider groups support the adoption of practices that will contribute to obesity prevention. Recommendations, toolkits, resources, and guides currently are available to encourage and assist health care providers in adopting approaches to care that promote the prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of overweight and obesity.

A number of initiatives designed to implement these recommendations have been undertaken. For example:

• Obesity prevention and treatment have been a strategic priority for the AAP for the past decade. The AAP also has a specific section on its website devoted to helping practitioners prevent and treat obesity, which includes practice tools, education and support, reimbursement information, and advocacy training (http://aap.org/obesity). In addition, Bright Futures, the AAP’s national health promotion and disease prevention initiative, addresses children’s health needs in the context of family and community (http://brightfutures.aap.org/). The AAP also has developed the Community Pediatrics Training Initiative program, which is “designed to improve residency training by supporting pediatricians in becoming leaders and advocates to create positive and lasting change on behalf of children’s health” (AAP, 2011). Through this program, faculty and residents are provided with training, technical assistance and resources, and networking and funding opportunities.

• The Let’s Move campaign (Let’s Move, 2011), in partnership with the AAP, is working with the broader medical community to educate health care providers about obesity and ensure that they regularly monitor children’s BMI, provide counseling on healthy eating early on, and even write prescriptions describing the simple things individuals and families can do to increase physical activity and healthy eating.

• The Texas Pediatric Society developed and distributed a toolkit to “aid pediatric practitioners in the prevention, early recognition, and clinical care of children and adolescents who are overweight or obese, with or without associated co-morbid conditions” (Texas Pediatric Society, 2008).

• The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association and the AAP developed a toolkit designed to help health care providers confront the obesity epidemic with their pediatric patients. It includes materials to help manage pediatric patients during office visits, guidelines that provide key assessment and diagnosis information, and tear-off patient chart sheets that can be used to track patient information (BCBSA, 2011).

• The American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) Healthier Life Steps program recently released the Physician’s Guide to Personal Health Toolkit, which includes tools to support the personal efforts of providers to live a healthier lifestyle and serve as role models for their patients (AMA, 2010).

• The National Association of School Nurses (NASN) has developed a continuing education program, School Nurse Childhood Obesity Prevention Education (S.C.O.P.E.), designed specifically for school nurses, that “provides strategies for school nurses to assist students, families and the school community to address the challenges of obesity and overweight” (NASN, 2011).

Several health professional groups advocate, or encourage advocacy among their members, for obesity prevention by supporting programs and changes in policy and by working to promote awareness of the issues involved. For example:

• The AAP has recommended that physicians and health care professionals work with families and communities and advocate for the encouragement of physical activity and improved nutrition, especially through in-school programs (Krebs and Jacobson, 2003). In addition, the AAP has called for a ban on all junk food and fast-food ads during children’s television shows as a means of slowing the rising tide of obesity. The statement also asks Congress, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Federal Communications Commission to eliminate junk food and fast-food ads on cell phones and other media, as well as to prohibit companies that make such products from paying to have their products featured in movies (Strasburger, 2011).

• The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, formerly known as the American Dietetic Association, has developed an integrated action plan for all of its registered dietitians and registered dietetic technicians, as well its organizational units, to work toward the prevention of childhood obesity. Included in this plan are strategies to expand the role of the registered dietitian from educator and counselor to advocate for community change and the promotion of healthy environments for children. The Commission on Dietetic Registration sponsors trainings for its members in its Childhood and Adolescent Weight Management program (Commission on Dietetic Registration, 2011). In addition, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation signature school-based nutrition education program, Energy Balance for Kids with Play (EB4K with Play), provides programming designed to result in behavior change in students through improvements in the school wellness environment and community and parental involvement, in addition to more traditional educational methods (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 2011).

• The American Nurses Association (ANA), which represents 2.9 million registered nurses (the largest group of health care providers), publically supports the Let’s Move campaign. It recognizes that “nurses have the capacity to touch the lives of parents and of children to help educate them on healthy choices,” and has pledged to support programs that address childhood obesity and to develop and distribute educational materials (ANA, 2010).

• The AAFP’s public health initiative Americans In Motion (AIM) is aimed at influencing the health of all Americans through “fitness” (physical activity, nutrition, and emotional well-being). AIM promotes family health care providers as fitness role models who serve as key resources for improving fitness among individuals, families, and communities. Additionally, the AAFP has stated that family health care providers should participate in local, state, and national efforts to prevent obesity and encourage physical activity for children, adolescents, and adults.

Together, these initiatives demonstrate institutional leadership in helping to train, support, and encourage health care providers to expand their role in current obesity prevention efforts.

Indicators for Assessing Progress in Obesity Prevention for Strategy 4-1

Process Indicators

• Increase in the proportion of primary care providers who regularly measure the body mass index of their patients.

Source for measuring indicator: National Survey on Energy Balance-Related Care Among Primary Care Physicians

• Increase in the proportion of physician office visits by children, adolescents, and adult patients that include counseling and/or education related to physical activity and nutrition.

Source for measuring indicator: NAMCS

NOTE: NAMCS = National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.

Insurers (both public and private) should ensure that health insurance coverage and access provisions address obesity prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

Potential actions include

• insurers, including self-insured organizations and employers, considering the inclusion of incentives in individual and family health plans for maintaining healthy lifestyles;

• insurers considering (1) benefit designs and programs that promote obesity screening and prevention and (2) innovative approaches to reimbursing for routine screening and obesity prevention services (including preconception counseling) in clinical practice and for monitoring the performance of these services in relation to obesity prevention; and

• insurers taking full advantage of obesity-related provisions in health care reform legislation.

Context

The adverse health effects of obesity (Calle and Thun, 2004; Eckel and Krauss, 1998; Preis et al., 2009) drive up health care costs (Thorpe et al., 2004). As described in Chapter 2, the estimated cost of obesity-related illness based on restricted-use data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey for 2000-2005 is $190.2 billion annually (in 2005 dollars), representing nearly 21 percent of national health care spending in the United States (Cawley and Meyerhoefer, 2011). Additionally, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) has estimated that $14 billion per year is spent on childhood obesity in direct health care costs (RWJF, 2007).

With more than 80 percent of Americans having health insurance coverage, private or public (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2011), health insurers should be interested in obesity prevention, diagnosis, screening, and treatment services as a way of reducing medical claims and associated costs. Obesity prevention and treatment services also should be a priority for federally qualified health centers, school-based wellness clinics, public health clinics, and other facilities affording the most vulnerable populations access to care.

Currently, some health plans and employers are addressing obesity for enrollees and employees, respectively, in the workplace (Simpson and Cooper, 2009), and

some health plans have provided and should continue to provide financial resources to support school-based initiatives to reverse childhood obesity (Dietz et al., 2007; Simpson and Cooper, 2009). Yet insurers do not consistently pay for obesity prevention and treatment services unless there are comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, or musculoskeletal issues. Obesity prevention should be considered a core service similar to cancer prevention screening and counseling.

Coverage of obesity prevention depends not only on health plans but also on employers. Two-thirds of insurance in the private market, while administered by health plans, is actually provided by self-insured employers, and a large number of businesses and organizations therefore have the ability to adjust benefits within their health plans (Heinen and Darling, 2009). In fact, health plans and businesses have embraced worker and workplace wellness programs that promote a healthier workforce and presumably reduce medical care costs (Heinen and Darling, 2009).

Health care insurers can address obesity by giving employers health plan options that include promising and innovative evidence-based strategies for encouraging policyholders and their families to maintain a healthy weight, increase physical activity, and improve the quality of their diet (IOM, 2005). Further, providing coverage for obesity treatment, prevention, screening, and diagnosis would give health care providers the opportunity and the means to provide the necessary care for each of their patients (whether diet and nutrition counseling, preconception counseling, or routine BMI screening).

Evidence

Although relatively little effort has been devoted to studying scientifically the specific impacts of various reimbursement and incentive approaches, evidence suggests that when one accounts for the high costs associated with obesity (see Chapter 2) over the long term, incentives for maintaining a healthy lifestyle become cost-effective, and in essence pay for themselves. Studies have shown that when employers and insurers provide incentives for weight loss and health maintenance, participants are more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors and are more likely to lose weight (Archer et al., 2011; Arterburn et al., 2008; Simpson and Cooper, 2009) (see also Strategy 4-3). However, most studies of incentive programs have included only adult participants, and the programs were provided at no cost (variables not yet studied include out-of-pocket cost, convenience, and time).

Data from the Diabetes Prevention Program reveal that weight loss (through physical activity and diet) was effective in lowering the incidence of diabetes in

individuals with prediabetes (NDIC, 2008). Additionally, emerging evidence suggests that obesity prevention efforts are especially important because, as a result of genetic and biological factors, people who become obese find it much more challenging to maintain any weight loss they may achieve (Sumithran et al., 2011). Moreover, while these physiologic compensatory mechanisms would be advantageous for a lean person in a food-scarce environment, energy-dense food is abundant and physical activity is largely unnecessary in most environments today, so relapse after weight loss is not surprising (Sumithran et al., 2011).

With respect to care delivery, health care providers often cite lack of reimbursement for obesity-related services as a barrier to providing such services (Cook et al., 2004). A survey of pediatricians found that for most, despite their knowledge of the problem and desire to address obesity prevention, inadequate reimbursement and lack of time were among major barriers to providing BMI screening and counseling during visits that were reported (Sesselberg et al., 2010). Although more evidence is needed to determine the most effective approaches, it is becoming clear that adequate coverage and reimbursement for obesity-related services are essential to addressing obesity prevention (Simpson and Cooper, 2009).

In sum, it is reasonable to believe that changes in health plan practices and policies could have a major effect on obesity prevention by reducing barriers to providing related care and incentives for engaging in a healthy lifestyle.

Implementation

While coverage for obesity-related health care services is highly variable, there has been some movement, especially over the past 5 years, toward providing reimbursement for obesity treatment and prevention in response to provider complaints and reevaluation of health plans by employers (Simpson and Cooper, 2009). Many employers also have begun to offer incentives or institute wellness policies that provide penalties or rewards based on an employees’ (and in some cases their dependents’) health status; often these incentives are monetary in nature (Mello and Rosenthal, 2008). Of note, in 2007 the Department of Labor released a clarification of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, ruling that employers can use financial incentives in wellness programs to motivate workers to get healthy (Mello and Rosenthal, 2008).

An example of a monetary incentive is a plan offered by United Healthcare, a national insurer, which for a typical family includes a $5,000 yearly deductible that can be reduced to $1,000 if an employee is not obese and does not smoke. Other examples of incentive programs are providing discounted insurance or

rebates for participation in health screening or the completion of weight loss or health education programs. Supporting such an approach, evidence from smoking cessation programs shows that full coverage or reimbursement improves quitting rates (Curry et al., 1998; Kaper et al., 2006). Insurers also have provided incentives to health care providers as a way to encourage BMI screening during pediatric visits (Simpson and Cooper, 2009).

At the state level, reimbursement for obesity-related services through Medicaid is highly variable. Despite documentation that coverage for obesity prevention in pediatric practice is available, many states are not aware of or create barriers to the delivery of such care (Simpson and Cooper, 2009). On the other hand, some states are promoting healthy behaviors through incentives for Medicaid and State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) participants (for example, awarding movie tickets, coupons, or gift certificates to parents who adhere to scheduled well-child visits). The Department of Health and Human Services recently announced that it will provide guidance for states on the inclusion of obesity services in Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefits. Provisions in federal health care reform legislation require health insurers and government health programs to provide more checkups, screenings, and health counseling with little or no copayment by the patient. In addition, the legislation includes preventive and wellness services as “essential benefits” and contains incentives intended to encourage employers to implement and sustain wellness programs. It also allows for employers or insurers to provide incentives, such as reduced premiums, for participation in qualifying wellness programs.

Indicators for Assessing Progress in Obesity Prevention for Strategy 4-2

Process Indicators

• Increase in the number of health plans that include incentives for maintaining healthy lifestyles.

Sources for measuring indicator: National Survey of Energy Balance-Related Care Among Primary Care Physicians and NAMCS

• Increase in the number of health plans that promote obesity screening and prevention and use innovative reimbursement strategies for screening and obesity prevention services.

Sources for measuring indicator: National Survey of Energy Balance-Related Care Among Primary Care Physicians and NAMCS

• Increase in the number of health plans reporting and achieving obesity prevention and screening metrics, including universal BMI assessment, weight assessment, and counseling on physical activity and nutrition for children, adolescents, and adults.

Source for measuring indicator: HEDIS

NOTE: BMI = body mass index; HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; NAMCS = National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.

Strategy 4-3: Encourage Active Living and Healthy Eating at Work

Worksites should create, or expand, healthy environments by establishing, implementing, and monitoring policy initiatives that support wellness.

Potential actions include

• public and private employers promoting healthy eating and active living in the worksite in their own institutional policies and practices by, for example, increasing opportunities for physical activity as part of a wellness/ health promotion program, providing access to and promotion of healthful foods and beverages, and offering health benefits that provide employees and their dependents coverage for obesity-related services and programs; and

• health care organizations and providers serving as models for the incorporation of healthy eating and active living into worksite practices and programs.

Context

Employed adults spend a quarter of their lives at the worksite (Goetzel et al., 2009), and worksites are potential settings for promoting healthy eating and active living among large numbers of adults of various socioeconomic levels and ethnic and cultural backgrounds (Quintiliani et al., 2007). Advances in technology and changes in the structure of many worksites have lead to an increase in sedentary, low-physical-activity occupations over the past several decades (Church et al., 2011). The resulting decrease in energy expended throughout the workday is associated with increases in BMI (Choi et al., 2010; Church et al., 2011). In addition, adverse work conditions, such as high-demand environments, low-control environments, and long hours, have been found to increase the risk of obesity (Schulte et al., 2007). The rising prevalence of obesity in the United States, particularly within the workforce, is increasing employer costs, economic and otherwise.

The costs and resource use associated with obesity in the workplace have been examined widely. Studies have found that overall, overweight or obese employees have higher sick leave use, absenteeism, use of disability benefits, workplace injuries, and health care costs and lower productivity and work attendance than normal-weight employees (Gates et al., 2008; Schmier et al., 2006; Trogdon et al., 2008) (an overview of the economic consequences of obesity is provided in Chapter 2 [Table 2-2]). These variables can total more than $600 per year for each obese employee compared with the costs associated with normal-weight employees. Overweight employees have been estimated to cost employers more than $200 per year compared with costs for those who are of normal weight (Goetzel et al., 2010).

The worksite is a key venue affecting employee wellness. Creating an emotionally and physically healthy workplace, supporting employees’ community-based physical activity, and offering onsite purchase of fruits and vegetables to bring home are examples of the potential results of a business focus on employee wellness. Worksite health promotion programs are employer initiatives designed to improve the health and well-being of workers (and often their dependents) and thereby reduce the costs associated with obesity in the workplace. These programs aim to prevent the onset of disease and to maintain health through primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention efforts. Primary prevention efforts in the workplace are directed at employed populations that are generally healthy, secondary prevention efforts are directed at individuals already at high risk because of certain lifestyle practices (such as smoking and maintaining a sedentary lifestyle), and tertiary prevention efforts focus on disease management (Goetzel and Ozminkowski, 2008).

Evidence

Worksites of all sizes represent an important venue (Schulte et al., 2008) for reaching the majority of the adult population. Worksite initiatives to promote and support healthy lifestyles have been shown to benefit both employers and employees (see Box 8-1) (CDC, 2011b).

Successful worksite wellness/health promotion programs have included strategies for providing employees with a healthy work environment; opportuni-

BOX 8-1

Potential Benefits of Workplace Wellness Programs

Potential benefits to employers:

• Reduces costs associated with chronic diseases

• Decreases absenteeism

• Reduces employee turnover

• Improves worker satisfaction

• Demonstrates concern for employees

• Improves morale

Potential benefits to employees:

• Ensures greater productivity

• Reduces absenteeism

• Improves fitness and health

• Provides social opportunity and a source of support within the workplace

SOURCE: CDC, 2011b.

ties for physical activity and health education; screening for obesity and related comorbidities; financial or nonmonetary incentives for participation in weight loss and/or health promotion efforts; and health benefit packages that include support for physical activity and nutrition (with respect to the latter feature, lack of health care coverage is associated with individuals forgoing needed care, including preventive care) (Archer et al., 2011; CDC, 2010; Romney et al., 2011). Some employees are willing to pay higher premiums for access to such wellness programs (Gabel et al., 2009).

The 2009 IOM report Local Government Actions to Prevent Childhood Obesity recommends that worksites, specifically those with high percentages of youth employees and government-run and -regulated worksites, develop policies and practices that build physical activity into routines (for example, exercise breaks at certain times of the day and in meetings or walking meetings) (IOM, 2009a). A review of the effectiveness of worksite physical activity and nutrition programs in promoting healthy weight among employees found that such programs had achieved modest improvements in employee weight status at 6- to 12-month follow-up (most of the studies examined in this review combined informational and behavioral strategies to influence physical activity and diet; fewer studies involved modifying the work environment [e.g., cafeteria, exercise facilities] to promote healthy choices) (Anderson et al., 2009).

Worksites also should ensure that healthy eating initiatives/programs are properly supported. One way of doing this is to ensure that employees (as well as guests, visitors, and clients/patients), have access to healthy food and beverage options if dining facilities, staff pantries, or vending machines are available in the work environment. There is strong evidence for the effectiveness of worksite obesity prevention and control programs that include improving access to healthy foods in vending machines and cafeterias (the report of the Healthy Eating Active Living Convergence Partnership provides several citations [Prevention Institute, 2008]) (see also Backman et al., 2011; Raulio et al., 2010).

Health promotion programs in the workplace are associated with reduced absenteeism, higher-quality performance and productivity, and lower health care costs (Aldana, 2001; Chapman, 2005; Goetzel and Ozminkowski, 2008; Heinen and Darling, 2009; Merrill et al., 2011; Pelletier, 2005). Therefore, such programs can be well worth the ongoing costs of their implementation (HHS, 2010) and can produce a direct financial return on investment (CDC, 2011b).

In sum, employers, while bearing both the direct medical and indirect productivity costs of obesity, have an opportunity to help increase and promote physical

activity, healthy eating, and overall well-being among a large proportion of the adult population.

Implementation

Movement toward employer-based wellness programs is already occurring. As of 2008, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 28 percent of full-time workers in the private sector and 54 percent of full-time workers in the public sector had access to worksite wellness programs, compared with 19 and 35 percent, respectively, a decade earlier (Stoltzfus, 2009). Additionally, in Washington State, for example, businesses, government agencies, and organizations came together to create the Access to Healthy Foods Coalition. Access to healthier options in the workplace is a goal of this coalition. In addition, making healthy foods and beverages available is part of a number of workplace wellness policies at large companies (examples include Power Group Companies, a Fortune 500 consulting firm, and Heinz, a global food company based in the United States). Health care reform legislation also may provide incentives for companies that offer workplace wellness solutions. Employers also could take advantage of existing stand-alone wellness, weight loss, physical activity, or incentive programs by providing access to or subsidizing membership fees for such programs during the work day or at the worksite. In the health care sector, several hospitals and health care organizations are already promoting active living and healthy eating. Examples include Health Care without Harm, a coalition that promotes a health care sector that does no harm and promotes the health of people and the environment; Kaiser Permanente’s comprehensive food policy to promote individual and environmental health (the Healthy Picks program); and the growing number of hospital farmers’ markets and gardens.

To aid employers in the development of worksite wellness programs, CDC developed LEAN Works, a free web-based resource that provides interactive tools and evidence-based resources to help employers design effective worksite obesity prevention and control programs (CDC, 2011b). In addition, employers can use CDC’s obesity cost calculator to estimate the cost of obesity to their business, as well as the amount of money that could be saved by implementing various workplace interventions (CDC, 2011b).

Indicators for Assessing Progress in Obesity Prevention for Strategy 4-3

Process Indicators

• Development by municipalities of incentive programs for employers of various sizes to support worksite-based physical activity promotion and nutrition education programs.

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

• Employers’ implementation of and support for physical activity promotion and nutrition education programs for employees.

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

Foundational Indicators

• Employers making obesity prevention a health priority for their workforce.

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

• Development and broad dissemination of measures with which to assess healthy workplaces supportive of physical activity and nutrition.

Source needed for measurement of indicator.

Health service providers and employers should adopt, implement, and monitor policies that support healthy weight gain during pregnancy and the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. Population disparities in breastfeeding should be specifically addressed at the federal, state, and local levels to remove barriers and promote targeted increases in breastfeeding initiation and continuation.

Potential actions include

• all those who provide health care or related services to women of childbearing age offering preconception counseling on the importance of conceiving at a healthy BMI;

• medical facilities, prenatal services, and community clinics adopting policies consistent with the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative;

• local health departments and community-based organizations, working with other segments of the health sector, providing information on breastfeeding and the availability of related classes to pregnant women and new mothers, connecting pregnant women and new mothers with breastfeeding support programs to help them make informed infant feeding decisions, and developing peer support programs that empower pregnant women and mothers to obtain the help and support they need from other mothers who have breastfed;

• workplaces instituting policies to support breastfeeding mothers, including ensuring both private space and adequate break time; and

• the federal government using Prevention Fund dollars to support implementation of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative nationwide, and providing funding to support community-level collaborative efforts and peer counseling with the aim of increasing the duration of breastfeeding.

Context

Primary prevention of obesity begins before birth. Women of childbearing age today are heavier, a greater percentage are entering pregnancy overweight or obese, and many are gaining too much weight during pregnancy (IOM, 2009b). One of the most important modifiers of weight gain in pregnancy and its impact on maternal and child health is a woman’s weight at the start of pregnancy (higher pregnancy weight gain has been associated with prepregnancy BMI) (IOM, 2009b). Addressing obesity prevention, intervention, and treatment in childhood and adolescence would result in young women entering their reproductive years at healthier weights. This is an example of taking a life-course approach to a healthy pregnancy and is important to reversing the transgenerational increase in obesity risk (Cnattingius et al., 2011).

Maternal gestational weight gain has been linked to obesity in childhood, as well as poorer maternal and infant outcomes (IOM, 2009a; Oken et al., 2007). Guidelines for maternal gestational weight gain have been released by

the IOM (2009a), but focused attention is necessary to ensure their widespread implementation.

In its reexamination of pregnancy weight guidelines IOM (2009a) recognizes that preconception counseling and support will be needed to assist mothers to enter pregnancy at a healthy weight, and in turn, have healthier pregnancies and healthier infants. After birth, support for breastfeeding as a primary strategy for obesity prevention requires a joint effort of hospital and outpatient services and community-based support through the engagement of employers and local health care providers. Helping mothers continue breastfeeding in the early postpartum period through 6 months requires a supportive environment at home, in the community, and in the workplace. Strategies to increase breastfeeding duration in the workplace have been successful, as has providing peer support. The current federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) regulations contain provisions that encourage women to breastfeed and provide appropriate nutritional support for breastfeeding participants (USDA/FNS, 2011). Strategies aimed at increasing breastfeeding initiation and maintenance are crucial to increasing the impact of breastfeeding on obesity prevention. Specific attention to the associations of breastfeeding with age and race/ethnicity would accelerate obesity prevention among the most vulnerable populations.

Evidence

Evidence suggests that preconceptional counseling improves women’s knowledge about pregnancy-related risk factors, including excessive weight gain, as well as their behaviors to mitigate those risks (Elsinga et al., 2008). Pre- and interconceptional counseling also improves attitudes and behavior with respect to physical activity and nutrition in response to behavioral interventions (Hillemeier et al., 2008). Pregnancy weight gain has been associated with several short- and long-term effects for mother and child. In particular, observational data are accumulating that link maternal weight gain and later childhood adiposity. There is also a strong association between high pregnancy weight gain and postpartum weight retention in mothers (IOM, 2009a).

After birth, breastfeeding has been shown to be associated with a reduced risk of obesity in the child (Ip et al., 2007, 2009), a protective effect that can persist into adulthood (Owen et al., 2005). Evidence suggests that initiation, longer duration, and exclusivity of breastfeeding provide a protective effect and lower odds of becoming overweight or obese in childhood and adolescence (Harder et al., 2005). A review of 22 systematic reviews on early-life determinants of overweight and

obesity found that breastfeeding may be a protective factor for later overweight and obesity (Monasta et al., 2010). A study of the association between breastfeeding and adiposity at age 3 years involving 884 children found that between birth and 6 months of age, infant weight change mediates associations of breastfeeding with BMI, but only partially mediates associations with indicators of child adiposity (van Rossem et al., 2011). And a study of another recent cohort of 5,047 children and their mothers in the Netherlands found that between 3 and 6 months of age, shorter breastfeeding duration and exclusivity during the first 6 months were associated with increased rates of growth, including weight and BMI (Durmus et al., 2011).

Additionally, a number of systematic reviews on the relationship between breastfeeding and childhood obesity have concluded that, as reported by the IOM (2011b), there is an association between breastfeeding and a reduction in obesity risk in childhood, although the nature of the study designs makes it difficult to infer causality. Several biologic mechanisms have been proposed to explain the effect of breastfeeding on obesity prevention, including that breastfeeding supports self-regulation of energy intake (Li et al., 2008, 2010; Mihrshahi et al., 2011; van Rossem et al., 2011).

Relative to breastfed infants, formula-fed infants exhibit higher and more prolonged insulin responses to feedings (Lucas et al., 1981; Manco et al., 2011), and this effect may persist into childhood. In obese children, formula feeding has been associated with reduced insulin sensitivity and increased insulin secretion relative to breastfed children with the same BMI (Manco et al., 2011). Moreover, factors present in breast milk but not in formula, such as leptin, a cytokine that controls satiety and energy balance, may confer an obesity protective effect (Singhal et al., 2002).

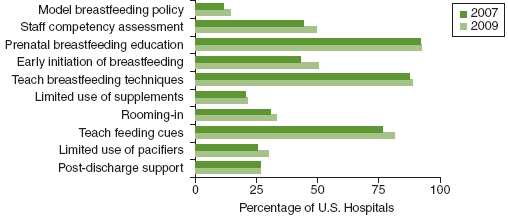

Breastfeeding has been endorsed as a strategy for obesity prevention by the IOM (2009b), CDC (2011c), the AAP (Gartner et al., 2005), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG, 2007), and the Endocrine Society (August et al., 2008). Significant gaps remain, however, in both breastfeeding initiation and maintenance. While Merewood and colleagues (2005) found that almost 82 percent of infants have ever breastfed, maintenance at 6 months dropped to 60 percent and exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months to 25 percent (CDC, 2011a). Breastfeeding initiation has been associated with having given birth in a Baby-Friendly Hospital (Merewood et al., 2005). Yet while many hospitals have made progress toward becoming Baby-Friendly (Figure 8-2) there were only two states as of 2009 in which more than 20 percent of births occurred at hospitals that had completed the 10 steps to certification as Baby-Friendly.

FIGURE 8-2 Percentage of U.S. hospitals with recommended policies and practices to support breastfeeding (2007 and 2009).

SOURCE: CDC, 2011d.

Implementation

The IOM has concluded that to improve maternal and child health outcomes, women not only should be within a normal BMI range when they conceive, but also should gain within the recommended guidelines (IOM, 2009b). To meet the recommendations for pregnancy weight gain, many women need preconception counseling, which may include plans for weight loss. Counseling is already an integral part of CDC’s preconception recommendations (Johnson et al., 2006), which are designed to enable women to enter pregnancy in optimal health, avoid adverse health outcomes associated with childbearing, and reduce disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes.

In 1991, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) launched the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative to ensure that all hospitals and birthing centers would offer optimal breastfeeding support. In 1997, Baby-Friendly USA was established as the national authority for the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative in the United States. Promotion and support of breastfeeding at birth through the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative has resulted in significant increases in breastfeeding rates (Perez-Escamilla, 2007). There is also a dose-response relationship between the number of Baby-Friendly steps (see Box 8-2) in place and successful breastfeeding. In one study, mothers who experienced none of the Baby-Friendly steps were eight times less likely to continue breastfeeding to 6 weeks than mothers experiencing at least five steps (DiGirolamo et al., 2001). The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative has developed a guidance document for overcoming barriers to implementation (Baby-Friendly USA, 2004).

BOX 8-2

10 Steps to Successful Breastfeeding

1. Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff.

2. Train all health care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy.

3. Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding.

4. Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within a half-hour of birth.

5. Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain even if they should be separated from their infants.

6. Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breastmilk, unless medically indicated.

7. Practice rooming-in—allow mothers and infants to remain together— 24 hours a day.

8. Encourage breastfeeding on demand.

9. Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (also called dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants.

10. Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic.

SOURCE: WHO/UNICEF, 1989.

Texas is one state where the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative has received strong support. According to Shealy and colleagues (2005, p. 5), “The Texas Hospital Association and the Texas Department of Health have jointly developed the Texas Ten Step Hospital Program to recognize Texas hospitals that have achieved at least 85 percent adherence to the WHO/UNICEF Ten Steps.

Certification is entirely voluntary and based on the hospitals’ reports; there are no external audits or site visits.”

Support for breastfeeding maintenance as mothers return home to their communities and workplaces is crucial. A supportive worksite environment helps support breastfeeding continuation (Galtry, 1997), while lack of accommodation for breastfeeding mothers contributes to shorter breastfeeding duration (Corbett-Dick and Bezek, 1997). Convincing evidence supports the role of corporate lactation programs in increasing breastfeeding maintenance (see Box 8-3 for an example). Workplace lactation support programs also have resulted in improved work experiences for breastfeeding mothers; improved productivity and staff loyalty; enhanced public image of the employer; and decreased absenteeism, health care costs, and employee turnover (Bar-Yam, 1997; Cohen et al., 1995; Dodgson and Duckett, 1997).

Of note, 24 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have laws regarding workplace lactation support. Provisions within the federal health care reform legislation specifically recommend that employers provide break time for employees to express breastmilk in a suitable space other than a bathroom for 1 year after their child’s birth.2 However, employers are not required to compensate employees for break time, and employers with fewer than 50 employees are exempt if the recommendations cause a hardship (U.S. Department of Labor, 2011). In addition, both the Surgeon General (HHS, 2011) and the report of the White House Obesity Task Force encourage workplace lactation support (White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity, 2010).

Studies of breastfeeding support have emphasized the “importance of person-centered communication skills and of relationships in supporting a woman to breastfeed” (Schmied et al., 2011, p. 58). Peer support programs are effective both independently and in combination with multifaceted interventions in increasing breastfeeding initiation and duration (Britton et al., 2007; Fairbank et al., 2000; Shealy et al., 2005). Home-visiting programs, which involve periodic visits by family health nurses or other health care providers, also have been found to be effective models for delivery of support for parents and their children, particularly for vulnerable populations, and have been found to be feasible options for addressing risk factors for childhood obesity (Hodnett and Roberts, 2000; Wen et al., 2009). Home-visiting programs are a method of care included within the federal health

![]()

2 See http://www.usbreastfeeding.org/Portals/0/Workplace/HR3590-Sec4207-Nursing-Mothers.pdf (accessed November 4, 2011).

BOX 8-3

Example of a Worksite Breastfeeding Initiative: California Public Health Foundation Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

According to Shealy and colleagues (2005, p. 10):

The California Public Health Foundation WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) agencies provide a breastfeeding support program for their employees, most of whom are paraprofessionals. The program includes encouraging and recognizing breastfeeding milestones and providing training on breastfeeding, monthly prenatal classes, postpartum support groups, and a supportive work site environment. The work site environment includes pumping facilities, flexible break times, and access to a breast pump. A program hallmark is access to an experienced colleague known as a Trained Lactation Coach, or TLC, who breastfed her own children after returning to work. An evaluation of the California program revealed that more than 99 percent of employees returning to work after giving birth initiated breastfeeding, and 69 percent of those employees breastfed at least 12 months. Access to breast pumps and support groups were significantly associated with the high breastfeeding duration rates (Whaley et al., 2002).

care reform legislation. An example of a comprehensive community breastfeeding support program is provided in Box 8-4.

Key factors in successful peer support groups include the following (Britton et al., 2007; Shealy et al., 2005; USDA/FNS, 2004)

• peer mothers of similar sociocultural background;

• paid counselors (who may be more effective than volunteers with respect to retention and ability to sustain the program);

• training of peer counselors in breastfeeding management, nutrition, infant growth and development, counseling techniques, and criteria for making referrals;

BOX 8-4

Example of a Community Support Program: The Breastfeeding Heritage and Pride Peer Counseling Program

As described by Shealy and colleagues (2005, p. 16):

The Breastfeeding: Heritage and Pride peer counseling program is a collaborative effort between Hartford (Connecticut) Hospital, the Hispanic Health Council, and the University of Connecticut’s Family Nutrition Program. Perinatal peer support is provided to low-income Latina women living in Hartford. The protocol calls for at least one home visit during the prenatal period. Counseling is provided once daily during the hospital stay. Hands-on assistance with positioning the infant’s body at the breast and latch is also provided, along with instruction on feeding cues and frequency, signs of adequate lactation, and managing common problems. Peer counselors are required to make three contacts after hospital discharge, with the initial contact made within 24 hours. The counselors must be high school graduates, have at least 6 months of breastfeeding experience, and successfully complete the training program. Training consists of 30 hours of formal, classroom instruction; 3-6 months of supervised work experience; biweekly case reviews; and continuing education. Peer counselors are paid and receive benefits if they work at least 20 hours per week.

• in both individual and group settings, peer counselors who are trained and are generally clinically monitored or overseen by a professional in lactation management support, such as an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC), nurse, nutritionist, or physician with specific training in skilled lactation care;

• leadership and support from management, staff access to IBCLCs, and community partnerships for making and receiving referrals; and

• integration of peer support within the overall health system, which appears to contribute to the ongoing maintenance of a program.

Indicators for Assessing Progress in Obesity Prevention for Strategy 4-4

Process Indicators

• Increase in the prevalence of initiation of any breastfeeding among new mothers.

Source for measuring indicator: CDC breastfeeding report card

• Increase in the prevalence and duration of exclusive breastfeeding among new mothers.

Source for measuring indicator: CDC breastfeeding report card

• Increase in the number of infants exclusively breastfed for 6 months.

Source for measuring indicator: CDC breastfeeding report card

• Increase in the percentage of U.S. hospitals with recommended policies and practices to support breastfeeding.

Source for measuring indicator: mPINC

• Increase in the percentage of U.S. workplaces with policies and practices that support breastfeeding.

Source for measuring indicator: IFPS-II (in development)

Foundational Indicator

• Elimination of disparities in breastfeeding initiation and maintenance.

Source for measuring indicator: NIS

NOTE: CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; IFPS-II = Infant Feeding Practices Survey II; mPINC = National Survey of Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care; NIS = National Immunization Survey.

INTEGRATION OF STRATEGIES FOR ACCELERATING PROGRESS IN OBESITY PREVENTION

The creation of systems to support healthy decision making at the community level is a necessary step linking individual health behavior change and choice to improvements in the physical and nutritional environments. Health care providers, employers, and insurers are all components of a system of support and service that enables individuals to access obesity prevention and treatment. However, these three components have tended to work independently. For example, individuals may hear messages in the workplace about healthy lifestyle change but have no access to additional visits with their health care provider or community resources because of a lack of health insurance coverage; conversely, individuals may see their health care provider for obesity treatment but lack healthy physical activity and nutrition choices at the worksite. Insurers may cover nutrition services but not physical activity. Integration of these interdependent entities can provide a system of community-level care with synergistic effects. Moreover, pregnant women and infants need to be surrounded by a system of broad-based support, with insurance coverage for all the services necessary to provide for a healthy pregnancy and early infancy. Health care providers and employers need to pay special attention to the support mothers and infants require to maintain healthy early infancy nutrition.

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2011. Community pediatrics training initiative. http://www.aap.org/commpeds/cpti/about.htm (accessed December 2, 2011).

Abramson, S., J. Stein, M. Schaufele, E. Frates, and S. Rogan. 2000. Personal exercise habits and counseling practices of primary care physicians: A national survey. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 10(1):40-48.

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2011. Energy balance 4 kids (EB4K) with play. http://www.eatright.org/Media/content.aspx?id=6442465058 (accessed November 22, 2011).

ACOG (American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). 2007. ACOG committee opinion no. 361: Breastfeeding: Maternal and infant aspects. Obstetrics and Gynecology 109(2 Pt. 1):479-480.

Aldana, S. G. 2001. Financial impact of health promotion programs: A comprehensive review of the literature. American Journal of Health Promotion 15(5):296-320.

AMA (American Medical Association). 2010. AMA healthier life steps: A physician’s guide to personal health program. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/public-health/promoting-healthy-lifestyles/healthier-life-steps-program/physicians-personal-health.page? (accessed August 15, 2011).

ANA (American Nurses Association). 2010. News release: American Nurses Association supports nation’s First Lady in combating childhood obesity. http://www.nursingworld.org/FunctionalMenuCategories/MediaResources/PressReleases/2010-PR/Efforts-against-Childhood-Obesity.pdf (accessed November 11, 2011).

Anderson, L. M., T. A. Quinn, K. Glanz, G. Ramirez, L. C. Kahwati, D. B. Johnson, L. R. Buchanan, W. R. Archer, S. Chattopadhyay, G. P. Kalra, and D. L. Katz. 2009. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 37(4):340-357.

Appel, L. J., J. M. Clark, H.-C. Yeh, N.-Y. Wang, J. W. Coughlin, G. Daumit, E. R. Miller, A. Dalcin, G. J. Jerome, S. Geller, G. Noronha, T. Pozefsky, J. Charleston, J. B. Reynolds, N. Durkin, R. R. Rubin, T. A. Louis, and F. L. Brancati. 2011. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. New England Journal of Medicine 365(21):1959-1968.

Archer, W. R., M. C. Batan, L. R. Buchanan, R. E. Soler, D. C. Ramsey, A. Kirchhofer, and M. Reyes. 2011. Promising practices for the prevention and control of obesity in the worksite. American Journal of Health Promotion 25(3):e12-e26.

Arterburn, D., E. O. Westbrook, C. J. Wiese, E. J. Ludman, D. C. Grossman, P. A. Fishman, E. A. Finkelstein, R. W. Jeffery, and A. Drewnowski. 2008. Insurance coverage and incentives for weight loss among adults with metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16(1):70-76.

August, G. P., S. Caprio, I. Fennoy, M. Freemark, F. R. Kaufman, R. H. Lustig, J. H. Silverstein, P. W. Speiser, D. M. Styne, and V. M. Montori. 2008. Prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline based on expert opinion. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 93(12):4576-4599.

Baby-Friendly USA. 2004. Overcoming barriers to implementing the ten steps to successful breastfeeding. http://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/eng/docs/BFUSAreport_complete.pdf (accessed July 3, 2011).

Backman, D., G. Gonzaga, S. Sugerman, D. Francis, and S. Cook. 2011. Effect of fresh fruit availability at worksites on the fruit and vegetable consumption of low-wage employees. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 43(4 Suppl. 2):S113-S121.

Barlow, S. E., W. H. Dietz, W. J. Klish, and F. L. Trowbridge. 2002. Medical evaluation of overweight children and adolescents: Reports from pediatricians, pediatric nurse practitioners, and registered dietitians. Pediatrics 110(1 Pt. 2):222-228.

Bar-Yam, N. 1997. Nursing mothers at work: An analysis of corporate and maternal strategies to support lactation in the workplace [dissertation]. Waltham, MA: Heller School, Brandeis University.

BCBSA (Blue Cross Blue Shield Association). 2011. Child obesity toolkit. http://www.bcbsnm.com/provider/clinical/childhood_obesity.html (accessed September 19, 2011).

Blumenthal, D. 2011. Wiring the health system—origins and provisions of a new federal program. New England Journal of Medicine 365(24):2323-2329.

Boyle, M., S. Lawrence, L. Schwarte, S. Samuels, and W. J. McCarthy. 2009. Health care providers’ perceived role in changing environments to promote healthy eating and physical activity: Baseline findings from health care providers participating in the healthy eating, active communities program. Pediatrics 123(Suppl. 5):S293-S300.

Britton, C., F. M. McCormick, M. J. Renfrew, A. Wade, and S. E. King. 2007. Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1):CD001141.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2010. Career guide to industries, 2010-11 edition, healthcare. http://www.bls.gov/oco/cg/cgs035.htm (accessed December 12, 2011).

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2011. The employment situation—November 2011. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf (accessed December 16, 2011).

Cahill, K., M. Moher, and T. Lancaster. 2008. Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database System Reviews (4):CD003440.

Calfas, K. J., B. J. Long, J. F. Sallis, W. J. Wooten, M. Pratt, and K. Patrick. 1996. A controlled trial of physician counseling to promote the adoption of physical activity. Preventive Medicine 25(3):225-233.

Calle, E. E., and M. J. Thun. 2004. Obesity and cancer. Oncogene 23(38):6365-6378.

Cawley, J., and C. Meyerhoefer. 2011. The medical care costs of obesity: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Health Economics. In press.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2010. Vital signs: Health insurance coverage and health care utilization—United States, 2006-2009 and January-March 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 59(44):1448-1454.

CDC. 2011a. Breastfeeding report card—United States, 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm (accessed August 3, 2011).

CDC. 2011b. CDC’s LEAN Works! A workplace obesity prevention program. http://www.cdc.gov/LEANWorks/ (accessed August 15, 2011).

CDC. 2011c. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60:1513-1519.

CDC. 2011d. Vital signs: Hospital support for breastfeeding. http://www.cdc.gov/VitalSigns/BreastFeeding/ (accessed August 3, 2011).

Chapman, L. S. 2005. Meta-evaluation of worksite health promotion economic return studies: 2005 update. American Journal of Health Promotion 19(6):1-11.

Choi, B., P. L. Schnall, H. Yang, M. Dobson, P. Landsbergis, L. Israel, R. Karasek, and D. Baker. 2010. Sedentary work, low physical job demand, and obesity in US workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 53(11):1088-1101.