|

Moderator: |

Joan Vernikos, Thirdage, LLC; Space Studies Board Member |

|

Speakers: |

Marc Kaufman, Journalist, The Washington Post Dietram A. Scheufele, Professor and Chair of Science Communications, University of Wisconsin, Madison Linda Billings, George Washington University School of Media and Public Affairs |

|

Panelists: |

Gregory Benford, Professor of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine Jean-Pierre Swings, Université de Liège (Belgium); Chair of the European Space Sciences Committee of the European Science Foundation |

Joan Vernikos, president of Thirdage LLC, former director of life sciences for NASA, and Space Studies Board member, served as moderator of the first of the two workshop sessions that focused more specifically on the communicators rather than the scientists. Reversing the format for the first six sessions, where scientists discussed the Grand Questions and then interacted with communicators through a panel discussion, in this session and Session 8, communicators discussed the theory and practice of communications and then interacted with scientists through a panel discussion.

Vernikos pointed out, however, that the title of this session uses the word “inspiring” not “communicating.” In order to communicate, she said, one must inspire. Storytelling, especially telling “your” story, is a good way to inspire, and she began by telling her own story of learning how one is expected to communicate as a scientist. She recounted that early in her career when she was ready to publish her first article in a journal that dates back to the 18th century (the Journal of Physiology in London), she read historical scientific papers that were written in the first person and found them compelling. She followed that example, but was dismayed when her adviser rebuked her because “we don’t do that.” She said that she does not know when scientists adopted the more anonymous method of communicating in the third person, but she wonders if today, with the social media, it is reverting to the first person.

Vernikos believes taxpayer-funded scientists have a responsibility to explain what they are doing to the public and thinks that what scientists are trying to do today is to “court” the public. As in other forms of courting, she continued, “you try to inspire your mate … and set up a level of attraction” and that is what scientists need to do with the public. A relationship needs to be established where each side trusts the other and information is exchanged. “We have to be prepared not to miss opportunities,” which means that “you need to know what you do” and be able to communicate it concisely. She challenged the scientists in the audience to tweet, in 140 characters, what each of them does. Excitement and passion are what capture people’s attention, and they want to know about the journey and the failures. People identify with failures because everyone is trying to solve problems, whether it is Sudoku, crossword puzzles, or the Grand Questions of science, she said.

Dietram A. Scheufele, professor and chair of science communication at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and co-principal investigator of the National Science Foundation’s Center for Nanotechnology and Society at Arizona State University, discussed the science of communicating with the public. He stressed that communications also may be an art, but it primarily is a science.

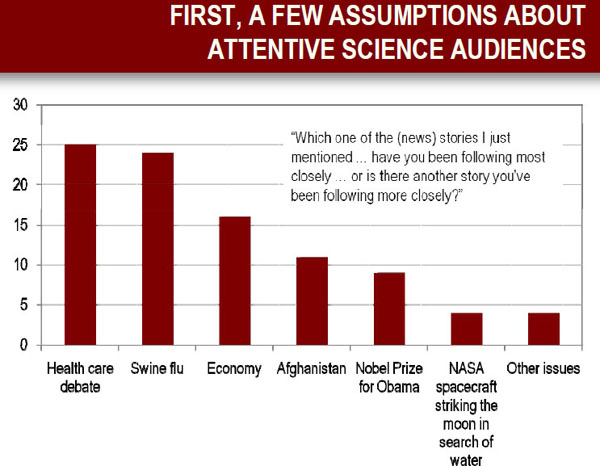

His themes were how audiences make sense of emerging technologies and how experience gained from communicating about past technologies can be applied to communicating about the space program. Showing data from the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, he pointed out that science has an audience, but it is not a large audience, and space is only a small part of that (Figure 14).

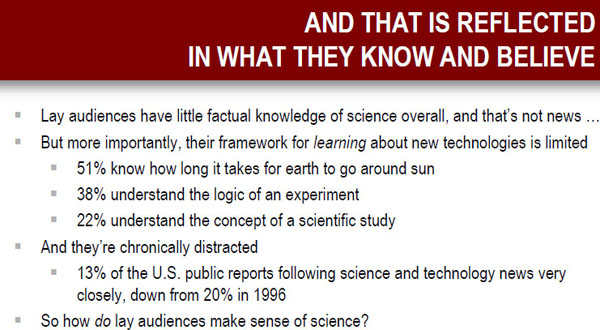

The public does not have a good understanding of science, Scheufele continued, showing data from the National Science Board that only 51 percent know how long it takes for Earth to go around the Sun, 33 percent understand the logic of an experiment, and 22 percent understand the concept of a scientific study (Figure 15).

It is a fact that scientists need to recognize. How, then, does the public make sense of science and technology? Science is just one of many decisions that people need to make every day, and they do it using “cognitive shortcuts”—”information shortcuts” or “heuristics”—where people make judgments based on information they already have.

Scheufele used the example of “Frankenfood,” a campaign by the environmental group Greenpeace against genetically engineered food in which the group altered the appearance of the cereal cartoon character “Tony the Tiger” on the cover of a box of Frosted Flakes to make it appear menacing and called it “Tony the Frankentiger, Genetically Frosted Flakes.” He said the campaign did not talk about facts at all, but was a powerful method for telling the public how to think.

How a topic is framed and what terminology is used therefore is critical in communicating. “Frames and narratives are powerful heuristics.” Scheufele gave an example of how terminology changed in the early days of the recent economic crisis. For about 2 days the story was “bank bailouts,” but it quickly changed to “rescues” because, while people do not want to bail out a bank, they do want to rescue the economy.

Scientists need to be proactive in communications because once labels are established, it is difficult to change them, he cautioned. For example, presidential science adviser John Holdren tried to change the terminology from “climate change” to “climate disruption” and was harshly criticized by Fox News.

Scheufele emphasized the need to connect with the public on their own “turf,” using as an example putting a banner along the sidelines of a soccer game saying “science for a better life.” Public values are important in understanding many of the emerging technologies and cause people to look at information differently. He cautioned against a widening “elite gap” where people with college educations increasingly are better educated about nanotechnology, for example, than high school graduates, showing data that as the information about nanotechnology became more complex between 2004 and 2007, the gap widened. He thinks the Internet and social media are emerging as effective tools for closing such gaps.

In closing, Scheufele listed five ways to ensure a communications failure:

• Be reactive instead of proactive, i.e., only start going public after a crisis/event occurs

• Address only issues and ignore values, emotions, etc., that people bring to the table

• Assume that science will ultimately prevail

• Assume that new and social media do not matter as much as traditional media

• Assume that communication is an art rather than a science

FIGURE 14 Comparison of audiences for different science topics. SOURCE: Dietram A. Scheufele, presentation to the workshop on Sharing the Adventure with the Public—The Value and Excitement of “Grand Questions” of Space Science and Exploration, November 10, 2010. Data from Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, conducted by Opinion Research Corporation, October 9-12, 2009, and based on 1,003 telephone interviews.

FIGURE 15 Public understanding of science. SOURCE: Dietram A. Scheufele, presentation to the workshop on Sharing the Adventure with the Public—The Value and Excitement of “Grand Questions” of Space Science and Exploration, November 10, 2010. Data from National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2010, National Science Foundation, Arlington, Va., retrieved March 3, 2010, from http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind10/.

Marc Kaufman, a journalist for the Washington Post who has recently written a book on astrobiology, used the sharing of newspaper stories via Facebook as an indicator of public interest in science. He began by noting that the most shared story that day on the New York Times website was about the discovery of large gas balls in the Milky Way by Dennis Overbye. That underscores the value and inspiration that science brings.

The newspaper business is going through “horrendous” changes that affect how much coverage there is of science issues. He is the only science reporter at the Washington Post and he also is an editor, so he cannot cover everything. The shrinkage is in newspapers, television, magazines, and elsewhere. Internet pressures mean shorter and shorter stories, but the Internet also lets the media know where the most interest is, and he thinks the public is extremely interested in science. The Gliese 581 story about a planet in a habitable zone around another star was the most shared story on Facebook for 2 or 3 days, demonstrating that people are interested in these topics.

Responses to space stories are interesting. NASA is among the biggest draws, and while NASA “properly” talks about the impact of its science for understanding and providing benefits to Earth, people really are interested in stories that respond to a sense “of potential transcendence, of curiosity answered, of wonder peaked,” like supermassive black holes or gas bubbles in the middle of the Milky Way. The space program provides “good news” and that is an “enormous opening for science news,” and while science writers are an endangered species, hopefully “we will not become extinct.”

The Facebook/Twitter era does not mean the end of the books, he hopes, since he just spent 2½ years writing a book on astrobiology. He believes people want long, as well as short, treatments of topics like that.

Crediting astrobiologist Pascale Ehrenfreund with the idea, he compared space science research with the television show CSI; both are forensics. He advocates a CSI-like show about space science, noting that the research would have to be speeded up to fit within 56 minutes.

“Exploration” does not get the same number of Facebook shares as science stories. “Science trumps [human] exploration by orders of magnitude,” he stated, adding that he believes commercial human spaceflight is a way to regain the public’s interest.

Linda Billings, research professor at George Washington University’s School of Public and Media Affairs and a principal investigator with NASA’s astrobiology program, commented that she is a “hybrid” of a scholar, like Scheufele, and a practitioner like Kaufman.

Public opinion research and studies of public understanding of science have shown how public interest does not necessarily lead to public understanding or public support. She is not convinced that “raising public awareness will build long-term constituencies for space exploration.” The Apollo program is an example of where public awareness was high, but public support was not.

She firmly believes that space exploration will continue to be the domain of government agencies for the foreseeable future, based on her 27 years of involvement in this field. The private sector’s interest is profit, not the public interest. A company’s marketing strategy is to sell a product or service, but marketing is not useful in selling government space programs. The space program has “advanced primarily by means of political interests rather than favorable public opinion.”

NASA adopted a “propagandistic model of communication” in the early days of space exploration to win over “hearts and minds to the cause of beating the Soviet Union into space,” Billings said. NASA and the space community have taken an “advertising and marketing approach” to “brand” and “sell” space, but what NASA has found is that public knowledge of space is a “mile wide and an inch deep.” Nonetheless, the space community still uses this one-way strategy—”package the message, shoot it at a target, make a bull’s eye.” This approach does not work in her opinion.

NASA is looking at new strategies today, she says. Billings believes that the key is “public participation in exploration planning and policy making,” although it is not easy and may not be enough. It would involve “community consultations, citizen advisory boards, and policy dialogues,” would be “complicated and time-consuming,” and require “power sharing.” It is a democratic approach, however, and in keeping with President Obama’s promise of “transparency, openness, and participation in government.”

Understanding the cultural environment and the interests of the public is important, and there is substantial data available for that purpose. A key lesson is that there “is no monolithic public” for space exploration, but many publics. Although many in the space community express the desire to improve public understanding, interest, and engagement, there is no evidence that it would lead to more public support, which is what they are actually seeking.

She stressed that “public information, public education, public interest, public engagement, public understanding, and public support are all different social processes and phenomena, and one does not necessarily lead to another.” Public participation is also different, and government agencies “tend to be resistant to true public participation in planning and policy making,” but that may be the only path to “enduring public involvement.”

The idea of space exploration—of human and robotic presence in space—interests the public as much as the “mechanics” of doing it.

The space community “continually underestimates its audiences,” Billings concluded, and should think “more broadly and deeply about the values, functions, and meanings of space exploration and worry less about marketing the concrete benefits.”

Gregory Benford, a professor of science journalism at the University of California, Irvine, and Jean-Pierre Swings, Chair of the European Space Sciences Committee, joined Vernikos, Scheufele, Kaufman, and Billings on the panel.

Vernikos started by emphasizing the importance of using the extent to which people forward a story to someone else as a measure of interest in the topic. It is also important to remember that actions speak louder than words whether they are spoken or written, and if words and actions are disparate the result is “disastrous.” If they are in concert, the “effectiveness is huge.” To her, for the human spaceflight program, the actions and words are disparate.

Saying he has published over 35 books, 100 magazine and newspaper articles, and 230 scientific papers, Benford agreed with Kaufman’s comments on print journalism. He said that scientists need to “manage” their stories in a world of a diminishing number of science writers. For example, he recently co-authored a paper on astrobiology that was picked up elsewhere and now has gotten 1.4 million Internet hits and appeared in more than 500 newspapers. The reason is that astrobiology sells, and what was new about his article was that it added up how much has been spent on the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence—tens of billions of dollars. When talking to journalists about the paper, he used a “pithy” way to engage with them by saying that when he grew up in Alabama his grandfather always said “Talk is cheap, whiskey costs money” and that was taken up in every story because people can relate to it.

Benford continued that it is important to “read the silences,” to look at the disconnect between a public face and what someone actually does. He thinks Billings’s talk did just that. If you want people to believe you want to do interplanetary travel, for example, the public needs to see that the necessary research and development is being undertaken. He listed a centrifugal gravity experiment in low Earth orbit to understand the effects of different gravity levels and a long-term closed biosphere experiment as examples of research and development that could be done now. He cited former NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin as saying that NASA has managed to turn adventure into a jobs program, and that is what Congress and the public sees.

Swings returned to the theme of inspiration and asked if there is still room for books in inspiring and educating young people. Kaufman said that he certainly thinks there is a future for books, but it is difficult to tell what will inspire people. “We are in the business of planting seeds” to see what will sprout.

Vernikos brought up the second space flight of John Glenn when he was 77 and how people thought it was a gimmick, but in fact very good life sciences data resulted from it. She agreed with Benford’s advocacy of a centrifuge but is convinced that the United States will not be the one to build it. Benford said he asked Daniel Goldin why a centrifuge was not built while he was NASA administrator. Benford said Goldin replied that Congress would look adversely at it because it would indicate that there really was an intention to do an interplanetary mission. Benford said that NASA “is a jobs program, but you don’t want it to be too large.” He continued on to say that Goldin worried that NASA would begin to be whittled away by 2020 because it would not have done anything interesting, and Benford believes that is coming true.

Scheufele said that the discussion so far was underselling Web 2.0, which he described as dialoging everything that happens online. People will be able to take short sections of books from their Kindles and put them on Facebook or Twitter and share it with everyone immediately. It will allow dialoguing across all of the new media tools. It lets someone build a “buzz” for whatever the message is. Even today many people will never read a book, but the messages from books reach them through other forms of communications. Web 2.0 and whatever comes after will be the key tools for this in the future.

Billings talked about non-profit media like ProPublica that focus on in-depth investigative reporting that no longer can be done in mainstream media because of budget cuts. There is no such place yet for science and technology topics, however, and she asked whether that would be worthwhile.

An audience member asked how to engage the public in the discussion of the future of human space exploration and keep it focused, rather than becoming an unconstrained national discussion.

Scheufele said that messaging is important, and one has to create an “I want to know more” reaction. Good research can tell each individual what words and messaging techniques to use, but that research has not been done for the space program “to build excitement and the eagerness to know more.”

Kaufman says that in Japan observatories are in public parks and are more open than here. He asked the director of one of them what people were interested in, and the director said the answer was overwhelming—where does the universe end and when will we find life. So in terms of the message of what NASA could be doing, we should tell the public we are on huge multi-decade endeavor to find life elsewhere, and that is a message people will respond to, he said.

Billings commented that she was involved in setting up town hall meetings for two different efforts in past years, but the shortcoming was that they came to an end. There was no sustained communication with that community of people.

Vernikos said that she sees a continuum among the Grand Questions, but somehow the universe and the search for life elsewhere has become a story that hangs together, while the story of humans in space does not. Efforts need to be taken to tie together space science and human exploration, to engage the public’s involvement through virtual interaction with robots, progressing through to human journeys, so that when a human goes everybody will be there with him.

Kaufman asked to make one last comment that he meant to make earlier and said that NASA public affairs “is far and away the best one I’ve dealt with. They answer the phone, they put people on the phone to give me answers, and they proactively give out information.” There may be problems with how the information is conveyed, but he thinks NASA deserves a “shout out” because it is doing a better job than most agencies.