2

The Human Element in International Polar Year 2007-2008

The wide-ranging and significant achievements of International Polar Year 2007-2008 (IPY) required the enterprise and commitment of myriad scientists, students, educators, local residents, logistics staff, program managers, and supporters—an estimated total of 50,000 people worldwide. They planned and executed the IPY programs and their direct interactions with the stakeholders and the general public brought IPY to life.

From the beginning, a major objective of IPY was to invest in “people”—that is, to expand human capacity in the quest for new scientific knowledge. This goal included increasing the numbers of current and future polar researchers (Figure 2.1) and integrating stakeholders in polar research, particularly polar residents.

A further major objective, strongly stated in the U.S. IPY Vision Report (NRC, 2004), was the creation of new connections between science and the public. The aim was effective communication of the physical and social polar sciences to increase understanding of the function of the poles in global systems. Efforts to achieve this goal engaged scientists, educators, and the media through a variety of innovative education and outreach programs.

EXPANDINGTHE POLAR RESEARCH COMMUNITY

U.S. and international polar scientists represent only a small fraction of the broader scientific community, even in the geophysical sciences.1 But the rapid and dramatic changes in the polar regions sparked both concerns about the future of the planet and the inquisitiveness of scientists from many disciplines, attracting them to investigate the many challenging scientific questions associated with these changes. The result was a measurable increase in the number of scientists conducting polar research.

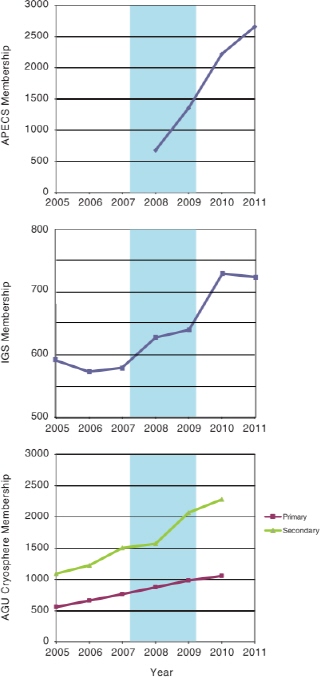

One indicator of growth during and immediately after IPY is the increase in U.S. and international membership of the International Glaciological Society (IGS; Figure 2.2). IGS represents scientists who research ice in any form (including at mid- or low latitudes as well as interplanetary ice), but the overwhelming majority are involved in polar research.

A similar trend is evident in the membership of the Cryospheric Sciences Focus Group, one of the newest in the American Geophysical Union (AGU) (Figure 2.2). In 2003 and 2004, the AGU convened multiple sessions related to IPY at its annual meeting to engage the community and communicate IPY planning in the United States.

IPY contributed to a growing trend toward international collaboration for polar science, thus marking

______________________

1 There were 1,057 members of the American Geophysical Union who in 2010 identified the Cryospheric section of AGU as their primary affiliation. Since 2001, membership in this section has increased slightly faster than the AGU membership as a whole. Cryospheric section members were 1.2% of AGU membership and are now 1.7% of total AGU membership as of 2011 (Anne Nolin, Oregon State University, personal communication).

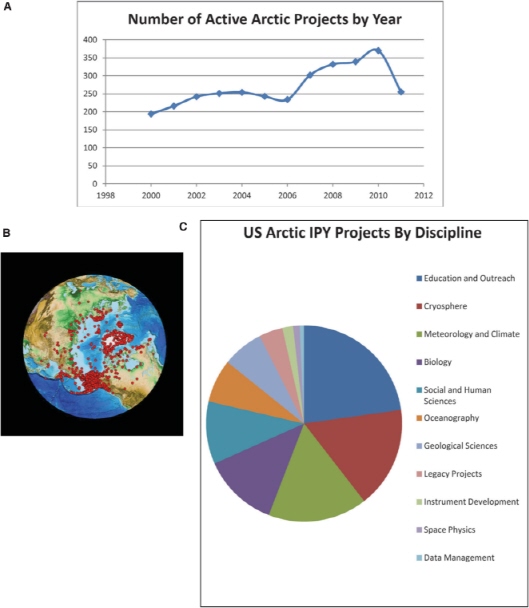

FIGURE 2.1 Data from ARMAP (Arctic Research Mapping Application) showing (A) the total number of NSF-funded field projects in the Arctic between 2000 and 2011, (B) the geographical distribution of those projects, and (C) the breakdown by discipline of the projects identified as IPY projects (of the 1,407 projects between 2000 and 2011, 188 were recognized by the National Science Foundation [NSF] as IPY projects). Most disciplines experienced a pulse of activity during IPY, especially in education and outreach; data management; and legacy projects, but there is evidence of a recent decline in the number of active projects in many regions and disciplines. Note that the ARMAP database includes only NSF-funded Arctic projects with a field-based component, so not all modeling or remote sensing projects are included. These graphics are intended to be representative of IPY efforts; they do not show the complete data for all of IPY. SOURCES: Craig Tweedie, University of Texas at El Paso; and http://www.armap.org.

FIGURE 2.2 The membership of polar professional associations grew during IPY. Shaded region represents the official time period of IPY (March 2007 to March 2009). Top: Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS) membership. Middle: Membership of the International Glaciological Society (IGS); the 2011 value includes members through August 2011. Bottom: Membership of the Cryosphere Focus Group of the American Geophysical Union. SOURCES: Data from Jenny Baeseman, APECS (top); Magnús Magnússon, IGS Office (middle); Anne Nolin, Oregon State University (bottom).

a radical departure from the previous polar/geophysical years, when most of the efforts were national in scope, logistics, and funding. The United States has been a global leader in polar research for years (Aksnes and Hessen, 2009)2 and is by far the largest contributor to research in both the Arctic and the Antarctic (followed by Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Norway, and Russia). IPY projects thus benefited from substantial U.S. participation and leadership. IPY’s focus on international partnerships motivated many researchers to expand their collaborations with scientists with similar interests in other nations. For an IPY project to receive ICSU-WMO endorsement, teams were required to include members from several nations. This cardinal feature gave IPY efforts an internationally recognized imprimatur and encouraged the leveraging of multinational infrastructure and intellectual assets, thus increasing the impact and capability of the project teams.

Measures to fuse international research teams into larger groupings addressing closely related topics were adopted by the IPY Joint Committee (JC) and International Programme Office (IPO) early in the planning process. In 2005 the IPO worked with the JC in a transparent process to collect and review more than 1,000 Expressions of Intent (short descriptions of proposed projects) and urged contributors to partner with other teams for larger or coordinated ventures. These Expressions of Intent eventually became 422 full proposals with broader focus and larger team size, and of these, 228 were recommended for implementation as “endorsed international projects” (Krupnik et al., 20113), including a number of large-scale international initiatives engaging scientists from multiple nations. Many projects featured particularly strong U.S. involvement, among them the Integrated Arctic Ocean Observing System (iAOOS4); Polar Study using Aircraft, Remote Sensing, Surface Measurements and

______________________

2 Aksnes and Hessen (2009) examine the period 1981-2007; there is an updated publication in preparation that examines more recent data including the IPY time period; the relative contributions of the countries listed here are unchanged (Dag Aksnes, Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research, and Education, personal communication).

3Understanding Earth’s Polar Challenges: International Polar Year 2007-2008 (Krupnik et al., 2011), is a summary report of IPY activities written by the JC. It includes coverage of IPY history as well as a broad overview of international contributions during IPY 2007-2008.

Models, of Climate, Chemistry, Aerosols, and Transport (POLARCAT5); GEOTRACES6; Census of Antarctic Marine Life (CAML7); Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program (CBMP8); Arctic Human Health Initiative (AHHI9); Antarctica’s Gamburtsev Province Project (AGAP10); and Norwegian-U.S. Traverse of East Antarctica.11 (See Chapter 3 for more information.) In addition, the United States funded IPY-relevant projects from national IPY solicitations that were not submitted to the JC vetting process.

Later in this chapter, a section on Diversity in the Polar Research Community highlights the sharp contrast in the participation of women since the IGY in 1957-1958: the number of female principal investigators has increased in the United States over the past 10 years and, whereas U.S. women were virtually absent from the IGY effort, they held strong leadership positions in all phases of the recent IPY.

IPY was tremendously important for engaging with Arctic communities, including capacity building in areas with little previous experience in polar research (Krupnik et al., 2011). One major result was a sea change in the degree of engagement and active participation of polar residents and indigenous peoples (see below and Chapter 5). Arctic residents participated in many IPY events, resulting in a sharing of observations and interpretations with scientists who often study the poles remotely or visit briefly during the summer. These expanded avenues of collegial interaction during IPY offered both polar researchers and Arctic residents more new and varied opportunities to enhance their understanding of the Arctic.

In addition to connections among scientists engaged in research, IPY outreach activities and special sessions at scientific meetings fostered communication and association. New levels of interaction inevitably developed as a result of scientists presenting their stories and results to audiences at numerous scientific, education, and outreach meetings over the almost 8-year-long period of IPY planning and implementation (2003-2010). This was certainly the case at large-scale international gatherings such as the AGU and European Geosciences Union meetings, the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research and the International Arctic Science Committee “open science” conferences, and the two major IPY conferences in 2008 in St. Petersburg and 2010 in Oslo, each of which engaged several thousand participants from many nations.

TRAINING YOUNG SCIENTISTS

Most of the science funded by the United States for IPY efforts included support for graduate or undergraduate students, who worked closely with students and faculty from other nations and became central players in both national and international projects. They were also involved in outreach, learning the importance of communicating science to a broader audience. Many of the projects focused on the Arctic created direct connections between the students and residents of the region, affording the students a true appreciation of the capabilities and experiences of residents and their adaptations to climate change.

An example of an IPY activity that facilitated interdisciplinary relationships among the new generation of polar researchers was the NSF-funded Next Generation Polar Research Symposium in 2008 (Weiler et al., 2008). This symposium enabled a diverse group of scientists new to the polar community to interact with both active and retired polar scientists and thus provided a new generation with a common sense of history and research connections for the future.

Another avenue of student participation was the University of the Arctic,12 a network of higher-education institutions and organizations established in 2001 to promote knowledge, research, and sustainability in the North. The network consists of over 130 member organizations across 8 nations and offers Arctic-focused courses and joint programs, often in partnership with indigenous peoples, and its membership and student enrollment have steadily increased since its inception. Its importance was evident during IPY as it helped to coordinate education and outreach activities associated with international research projects.

______________________

10www.ldeo.columbia.edu/res/pi/gambit/.

An outstanding success of IPY was the establishment in 2006 of the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS13). Sparked by a small core of enthusiastic and imaginative young polar scientists and a supportive IPO, the group made the most of the quick and effective social networking tools that are especially familiar to the young in this era of global electronic communications. APECS has already become “the preeminent international organization for polar researchers at the beginning or early stages of their careers.”14 This self-started activity so fully addressed the IPY objective of engaging young scientists in polar research that APECS developed its own early-career program and integrated it into the overall suite of IPY activities.

APECS achievements during IPY included the creation of an international and interdisciplinary network for early career polar scientists to share ideas, develop new research directions, and form collaborations; promotion of education and outreach as integral components of polar research to stimulate future generations of polar researchers; and arrangement of opportunities for professional career development through webinars, workshops, and session leadership at symposia. Indeed, the participation of APECS members among the speakers, planners, and session cochairs of major IPY-related meetings became essential.

APECS has grown at an extraordinary rate, to a total of 2,652 members from 45 countries as of July 2011 (Figure 2.2); nearly 20 percent (499) of APECS members are in the United States. APECS receives increasing support and endorsement from many international organizations. Importantly, the association has not only survived the rapidly changing careers of its leadership but thrived as creativity and energy are replenished, making it one of the most vibrant legacies of IPY. APECS is a model to inspire youth to consider the exciting and rewarding potential of a polar research career.

INCREASING DIVERSITY

The polar research community has never been particularly diverse—50 years ago, planning for U.S. efforts in the IGY was carried out by an all-male committee. In contrast, women had strong leadership roles in planning U.S. involvement in IPY 2007-2008. There was a female director of the Polar Research Board (PRB), a female chair of the PRB during most of the IPY years, and a female chair of the U.S. National Committee for IPY Vision (NRC, 2004).

Similarly, a significant difference between IPY 2007-2008 and its predecessors was the participation of women in project leadership and participation—an increase from almost no female leads during IGY to around one-fourth during IPY. As shown in Table 2.1, during the 10 years from 1999 to 2009, the number of female project leaders increased by 10 percent, with an overall increase of 6 percent during that period in women among principal and coprincipal investigators. Despite recent developments, women and indigenous peoples in particular remain underrepresented.15

The research community remains far less diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, but IPY offered an excellent opportunity to increase diversity through the involvement of graduate and undergraduate students in the science programs (Figure 2.3). For example, the Dartmouth College NSF-funded IGERT (Interdisciplinary

TABLE 2.1 NSF/OPP Grant Recipients by Gender, 1997-1999 and 2007-2009

| PI | Co-PI | Total | ||||||

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 1997-99 | 742 | 84% | 16% | 330 | 76% | 24% | 82% | 18% |

| 2007-09 | 1051 | 74% | 26% | 521 | 79% | 21% | 76% | 24% |

| NOTE: To assess the participation of women in IPY, projects supported by the NSF Office of Polar Programs (OPP) were targeted as a representative sample. Note that these may include education and outreach as well as research projects supported by OPP. Grant recipients were categorized by gender in both 1997-1999 (n=1072) and 2007-2009 (n=1572), by denoting gender-obvious names (e.g., “John” = male; “Clara” = female) and researching and clarifying the remaining names. Genders were thus determined for more than 99 percent of principal investigator (PI) names. SOURCE: Data from http://www.nsf.gov. | ||||||||

______________________

14 Jenny Baeseman, APECS Director, personal communication, 2011.

15 www.ldeo.columbia.edu/res/pi/polar_workshop/strategies/communities.html.

FIGURE 2.3 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) field engineer Beth Burthon (left) and graduate student Adrienne Block (right) from Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory analyze data in the field as part of Antarctica’s Gamburtsev Province project. SOURCE: Robin Bell.

Graduate Education, Research, and Training) program on Polar Environmental Change, which started during IPY in partnership with Greenlander Aqqaluk Lynge and the Inuit Circumpolar Council of Greenland, was successful in recruiting minorities to this interdisciplinary PhD program; among others, a female Native American biologist and black female electrical engineer are completing their PhD degrees. Another example is the Research and Educational Opportunities in Antarctica for Minorities (IPY-ROAM) program,16 in which university students and high school teachers travel to Antarctica and learn firsthand about research in the field.g70

Some IPY outreach activities specifically targeted certain audiences to deliver the message that polar research is an equal-opportunity career choice. Of particular note was the 2008 National Annual Conference of the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science titled “International Polar Year: Global Change in Our Communities.”17 The meeting, which resulted from the determined efforts of the IPO, enabled an important dialogue among Native Elders, students, and polar scientists from many disciplines about the health of the poles, polar peoples, global climate concerns, and ways to make positive contributions to the sustainability of the planet.

ENGAGING POLAR RESIDENTS AND BUILDING COMMUNITY CAPACITY

IPY represented a sea change in bringing Arctic residents and indigenous peoples into polar research. Both constituencies were valuable contributing members to IPY activities by virtue of their expert knowledge of local environments and their involvement in IPY data collection, local observations, and education and outreach activities.

Many IPY projects encouraged this trend through grants that fostered collaboration with indigenous people and through student training about the importance of local communities and of good communication with people living in the Arctic. This was a particularly notable aspect of IPY as Arctic residents had little if any role in the earlier IGY/IPYs, whereas in IPY 2007-2008 they launched or led four projects and were active in more than 20 others (Gofman and Dickson, 2011). Also of particular importance was the participation of indigenous experts—elders, hunters, reindeer herders, and others—as long-time environmental monitors and researchers in several IPY projects, such as Sea Ice Knowledge and Use (Krupnik et al., 2010b), the Bering Sea Sub-Network (BSSN18), EALÁT (Reindeer Herders Vulnerability Network Study19), and others.

IPY promoted the practice of returning usable data to communities (see section in Chapter 5 on “Providing Critical Information to Users and Decision Makers”). Furthermore, for the first time IPY data were collected and disseminated in indigenous languages: Inuit (Inuktitut, Kalaallit, Iñupiaq, Yup’ik, and Yupik), Gwich’in, Sámi, Chukchi, Sakha, and Nenents. Also for the first time, IPY activities documented and supported indigenous languages and knowledge in the Arctic regions, including endangered Native languages (in Alaska), knowledge of marine animals, terrestrial animals, and sea ice (funded by NSF and the National Park Service [NPS]).

These successes were despite the fact that few if any indigenous representatives were active on the IPY governing bodies at either the international or national level (Krupnik et al., 2011). Also, the impact of IPY was very uneven across polar communities. Some (e.g., Barrow, Togiak, and Gambell in Alaska; Igloolik,

______________________

Clyde River, and Iqaluit in Canada; and Kautokeino in Norway) were actively engaged and informed, whereas many more had sporadic or ad hoc access to IPY information and resources. This is a valuable lesson for future planning.

U.S. scientists, together with their colleagues from Canada, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and Greenland, were at the forefront of partnerships with polar residents, as almost a dozen U.S. IPY projects funded by NSF, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), USGS, NPS, and other agencies engaged northern residents and indigenous people in data collection and other research activities. Research grants to nonacademic groups further expanded and diversified the body of polar researchers during IPY20.

Such grants were fairly unusual for the NSF OPP, and the committee applauds the OPP for thus enabling organizations that had longstanding relationships with local communities to conduct some IPY activities, including targeted workshops, websites, webinars, exhibits, popular books, performance art, teacher training, and public programs. Several activities targeted families and children with the aim of exciting future generations in polar research and showing parents what was being learned and why it mattered. Examples of these programs include “Beyond Penguins and Polar Bears: Integrating Literacy and the IPY in the K-5 Classroom” at Ohio State University, and “Penguins Teaching the Science of Climate Change” by Harvey Associates.21

In addition to special events for different audiences (e.g., the general public, government officials, educators, schoolchildren, and nongovernmental organizations), IPY featured broadscale public activities, starting from its official opening in March 2007. Most notable were seven online “International Polar Days”22 (some of which actually lasted a full week) that featured IPY activities about sea ice (September 2007), ice sheets (December 2007), changing Earth (March 2008), land and life (June 2008), people (September 2008), outer space (December 2008), and polar oceans and marine life (March 2009). Two polar weeks in October 2009 and March 2010 focused on community building.

In the United States, “Polar Weekend” science fairs provided a forum for polar researchers, educators, and performers to engage with a public audience through hands-on displays and presentations. There were three such events in New York at the American Museum of Natural History (2007, 2008, 2009, with more than 12,000 visitors) and two in Baltimore at the Maryland Science Center (2009, 2010). Each fair involved about 100 presenters/volunteers representing about 30 institutions. Recurring Polar Weekends were also held in Seattle, Washington, and Fairbanks, Alaska; and sporadically at other locations including Kansas, Michigan, and Illinois. Surveys indicated that the public strongly valued these face-to-face interdisciplinary programs. By engaging participants in developing presentations, activities, and resources for the general public, these fairs also built the capacity of polar researchers to become active and articulate spokespeople during IPY and beyond. A large proportion of the participants (46 percent) indicated that “communicating with the public is now something I consider part of my career.”23

The Exploratorium, a museum in San Francisco, put the power of the camera and written word into the hands of researchers in producing “Ice Stories,” an online resource that engaged the public in the adventures of polar researchers in their pursuit of scientific discoveries. Two years of webcasts from the Arctic and Antarctic provided an “up close and personal” look intended to help the public relate to science and scientists.

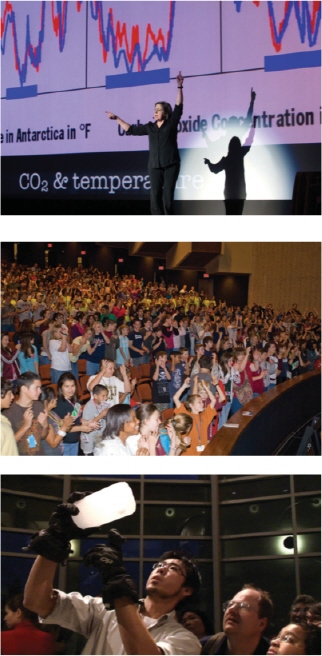

Of the myriad IPY outreach activities, the jointly funded NSF and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Polar-Palooza24 project had a particularly high public profile. Its cadre of 34 polar scientists and Arctic spokespeople performed at 24 museums and science centers across the United States before extending the group’s reach to venues in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, Norway, and Russia, and the podcasts and online activities and materials were used in many more countries.

Polar-Palooza’s “Stories from a Changing Planet” consisted of a professionally produced stage show with exciting music and stunning photography as a backdrop against which scientists and Arctic residents presented

______________________

20 http://www.nsf.gov/od/opp/ipy/awds_lists/final_awrds_lists/ipy_awrds_rev02032011.pdf.

21http://www.nsf.gov/od/opp/ipy/awds_lists/2010_awds/ehr_awds.jsp .

22 http://ipy.arcticportal.org/feature/item/1113.

23 Stephanie Pfirman, Barnard College, personal communication, 2011.

important scientific data and compelling research. These efforts complemented academic programs to train students to work with local communities. Eventually, the combination of these two efforts should continue to benefit both research and local polar communities, promoting not only more rigorous research methods but also greater communication, trust, and collaboration between the two communities.

COMMUNICATING WITH THE PUBLIC

Extensive outreach and communication of science results to the public were a priority objective of U.S. IPY activities (NRC, 2004). As a result, each project had to include outreach and education activities as a condition of endorsement. In addition, 57 of the international IPY projects (out of more than 228 total) specifically focused on communicating IPY science to the broader science community, students, educators, policymakers, and general public in a variety of personal experiences (Figure 2.4). The show enabled face-toface discussions between Arctic residents experiencing the undeniable impacts of climate change and midlatitude citizens for whom the concept of climate change was still difficult to comprehend. The opportunity to meet a polar researcher “in the flesh,” to hold the tools used, and to see a real ice core were all powerful methods of engagement.25 The stage shows were often accompanied by additional pole-related activities in local museums and visits to schools to further the engagement of polar researchers with public audiences, educators, and schoolchildren.

Formal outreach activities included organizer and participant evaluations to quantify their effectiveness. These assessments showed that many outreach activities were successful in informing their audiences of the seriousness of observed changes in polar and global climate and of the role of polar research in supporting those conclusions (Perry and Gyllenhaal, 2010). According to the assessment report for Polar-Palooza,

There were strong indications that the Polar-Palooza model of using real scientists and Alaska Natives as presenters worked very well for most Polar-Palooza audience members, whether they attended and participated in the presentations, the educator workshops, and/or the outreach activities and events. Under the guidance of Polar-Palooza staff working with them both in advance and “’on-the-fly,”’ the… presentations and the multimedia framework of graphics and highdefinition video formed an engaging and coherent whole for most respondents. (Perry and Gyllenhaal, 2010)

Although the IPY community receives admiration and acclamation for its collective accomplishments in education and outreach, it has been suggested that more tangible means for professional recognition need to be developed (Salmon et al., 2011). What the research community learned, in return for their efforts, is that the human dimension is essential not only in the conduct of science but also in its communication. Participant feedback repeatedly indicated that the adventure of the endeavors, the importance of the science, and the thrill of discovery were essential to engaging the public.

PROVIDING RESOURCES FOR TEACHERS

The effort of informing teachers and other educators about polar science can have long-term benefits, and IPY included a number of programs that engaged teachers. IPY scientists worked with the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) to reach science teachers around the world. NSTA coordinated several symposia (face-to-face workshops) at their area and national conferences, and many teachers said that direct access to scientists was one of the most exciting and valuable features of the programs. NSTA also worked with representatives of multiple federal agencies (NASA, NOAA, and NSF) and produced effective web seminars (webinars) using the association’s expertise, access to a network of 400,000 science teachers, and portal (the NSTA Learning Center). Of enduring benefit are dozens of webinar archives and podcasts that are available to all teachers free of charge and on demand via the Learning Center—“evergreen” productions that teachers consume on a regular basis. Science teachers can use these resources for years to come to inform students, illuminate the human dimension of polar research (e.g., by talking about science careers), and hence increase the human capacity of polar research.

______________________

FIGURE 2.4 Photos from Polar-Palooza events. Top left: Mary Albert explains carbon dioxide and temperature data from the Vostok ice core. Middle left: Audience at a Polar-Palooza Event. Bottom left: Graduate student Atsu Muto describes the archiving of ancient atmospheres in bubbles in the polar ice sheets to local citizens. Right: Polar biologist Dr. Michael Castellini assists a ìmidlatitude penguinî in answering questions from the audience at the Polar-Palooza event in Fort Worth, Texas. SOURCES: Geoffrey Haines-Stiles and Polar-Palooza website (http://passporttoknowledge.com/polar-palooza).

Prepared teaching lesson plans that explicitly address national science standards and other curriculum requirements were made available to teachers. Many of the larger IPY science programs included an education and outreach office to create materials for teachers. One such program is Antarctic Geological Drilling (ANDRILL), which created a variety of programs and activities for teachers during the IPY years as well as an education event for teachers at the IPY Oslo Science Conference in 2010.26

A science education initiative that reached large numbers of teachers and their students in the United States and other countries was Monitoring Seasons through Global Learning Communities, also called GLOBE (Global Learning and Observations to

______________________

Benefit the Environment) Seasons and Biomes.27 This inquiry-based project monitors seasons, and specifically their interannual variability, to increase students’ understanding of the Earth system (its focus has progressed from the tundra and taiga biomes to temperate, tropical, and subtropical forests, grasslands, savannahs, and shrublands). It links students, teachers, scientists, citizens, and local experts in more than 50 countries. Seasons and Biomes has conducted 32 professional development workshops for 600 educators and scientists, and those who have been trained conducted an additional 23 workshops for 436 teachers and 20 preservice teachers, reaching more than 1,000 educators and an estimated total of 20,000 students from all over the world.

PolarTREC (Teachers and Researchers Exploring and Collaborating) is an NSF-sponsored program that pairs K-12 public school teachers with scientists working in the field in the Arctic and Antarctic. The teachers participate in a science field team in the Arctic or Antarctic and relay their experiences and adventures to students at home and around the world through blogs and webinars. Once the field season ends, the researchers traveled to the teachers’ schools to make presentations about the science and talk with the students.

During IPY, PolarTREC enabled 48 teachers (from elementary through high school) to engage approximately 5,000 students in polar research activities.28 Students and teachers alike reported an increase in their understanding of the polar regions and of scientific processes and practices after the PolarTREC experience. Similarly, scientists that participated in the program found that they were able to better communicate science to a K-12 audience. The PolarTREC website29 serves as an archive of webinars and other resources for classroom activities.

MAINTAINING AND INCREASING HUMAN CAPACITY

IPY invested heavily in the development of younger scholars, partnerships with polar residents, training of school teachers and students, and outreach to the general public, all with the goal of increasing the human capacity of polar science. There is early evidence that these “people-focused” IPY activities were positively received and will support further efforts to inform and engage the public in polar issues. Continuing efforts may build on the fact that polar research yields important results that are of interest to the public as a useful source of information about large-scale climate changes and their societal impacts. Whether in the physical or social sciences, human health or public policy, there is a lot of information of use to diverse audiences. The need for experts in all these fields to investigate, understand, and respond to change is imperative.

Follow-up studies are the only certain means to track the staying power of the many IPY outreach efforts. Decadal or half-decadal surveys of indicators—such as the number of active researchers in various disciplines, number of polar residents and communities partnering with scientists, and public knowledge of polar-related issues—would be very useful to the long-term assessment of IPY.

CONCLUSIONS

The committee identified the following positive outcomes of IPY efforts designed to engage the public and build human capacity for polar research:

• The emergence of the young scientists' peer network APECS, which provided a means for early career scientists in various countries to share ideas, develop new research directions, and form collaborations;

• The University of the Arctic, a network of higher-education institutions and organizations, helped to coordinate education and outreach activities internationally;

• Major increases in the numbers of researchers, women, and polar residents actively involved in polar research;

• A significant expansion of collegial links between experienced and new polar researchers, which

______________________

27 http://classic.ipy.org/development/eoi/details.php?id=278.

28www.polartrec.com/expeditions/prehistoric-human-response-toclimate-change-2010.

in turn benefited the creation of complex international projects;

• A new era of extensive and effective outreach and educational activities, in which polar science garnered increased attention and was enthusiastically received;

• The engagement with and inspiration of teachers by polar scientists through the extensive network of teachers associated with the NSTA, as well as the legacy of webinars and classroom materials that met national standards for education and provided a long-term repository of resources and activities; and

• A new impetus to engage educators in teaching polar sciences, and to use polar science to draw students into science more broadly, matched by an increased level of activity in the polar research community to meet the needs of teachers and their students.

The education and outreach efforts during IPY raised the bar for the quality of scientist interactions with teachers, students, and the public in ways that increase public understanding of science. Continued funding for strong and effective outreach activities such as those described in this section is critical to continued public engagement in and understanding of polar science.