Progress, Needs, and Lessons Learned: Perspectives from Six Countries

In setting the context for the workshop discussions, Peter Lamptey noted that of the 57 million deaths that occurred worldwide in 2008, 63 percent, or roughly 36 million, were caused by noncommunicable diseases. Of the 63 percent of deaths caused by noncommunicable diseases, 48 percent (or 30 percent of all deaths) were caused by cardiovascular disease, 21 percent (13 percent of all deaths) by cancer, and 12 percent (7 percent of all deaths) by chronic respiratory disease and diabetes (Alwan et al., 2011). These are the “big four,” he said, and several common risk factors are principally responsible for the disease burden from these four. Tobacco use is by far the most devastating contributor. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 6 million people die from tobacco- or second-hand smoke–related diseases each year. Smoking is estimated to cause 71 percent of lung cancer cases, 42 percent of chronic respiratory disease, and 10 percent of cardiovascular disease (Alwan et al., 2011). Insufficient physical activity, unhealthy diets, and alcohol overconsumption are other prominent risk factors that contribute to a large portion of the global chronic disease burden globally (Alwan et al., 2011). The WHO has set targets for reducing tobacco use and alcohol consumption and improving diets as well as lowering blood pressure and slowing the increase in obesity, which by itself contributes to at least 2.8 million deaths per year (Alwan et al., 2011).

In addition to these major categories of chronic disease and major risk factors, Lamptey said that many countries also have a high burden of other chronic conditions, including mental health problems, the effects of injuries, sickle cell disease, and renal disease, as well as infections such as

human papillomavirus, hepatitis, and helicobacter pylori that contribute to chronic disease.

Global statistics provide a window into the magnitude of the chronic disease burden worldwide, but do not reflect variations that exist across countries—especially low- and middle-income counties. Therefore, the opening session of the workshop provided an opportunity to explore the distinct conditions and capacities of six countries—Grenada, Kenya, Bangladesh, Rwanda, India (from the subnational perspective of the state of Kerala), and Chile. These economically, geographically, and demographically diverse countries illustrated the significant variations that can exist regarding the contributions of particular diseases to national chronic disease burdens, how chronic diseases fit in with other health issues, the challenges that countries face when attempting to address chronic diseases, and the degree to which countries have or are able to address these challenges. The exploration of the progress and challenges in these countries’ chronic disease efforts provided a jumping-off point to discuss the importance of local context when considering tools that might be useful to inform country-level decision making to address chronic diseases.

Dr. Lamptey explained that presenters from each of the countries were asked to describe the current national disease burden along with such relevant factors as policies, the health infrastructure, and information management systems. They were also asked to describe existing chronic disease control programs, the role of civil society, and public–private partnerships, with the goal of helping to highlight gaps in disease control efforts and opportunities for improvement.

Lamptey identified a number of specific questions for discussion:

• Why has the public health community taken so long to move past the myth that chronic diseases are primarily problems in the industrialized world and how can the community make sure the myth no longer impedes policy or funding for combating these diseases in developing nations?

• Why has the demand for action on chronic diseases—from donors, international institutions, national governments, and communities—been so muted?

• How can the public health community better combat the myth that chronic diseases are difficult to prevent and expensive to treat?

• What has prompted some countries to take significant action on these diseases and what lessons do these countries offer?

• The WHO has proposed that the state of a country’s health services be used as a gauge of its ability to respond to chronic diseases. In some countries, HIV funding has helped to strengthen health systems in many ways, but it has neglected other elements of it. For

example, in one HIV clinic in Zambia, the staff do not routinely measure blood pressure. In one regional hospital in Ghana, the laboratory is state of the art, while the emergency room is “18th century.” How can this be rectified so that health systems can adequately address chronic diseases?

GRENADA

The government of Grenada views health as a basic human right as well as a vehicle for economic growth and social development, as Dr. Francis Martin, director of primary health care for the Ministry of Health in Granada, explained. The health care system in Grenada emphasizes primary prevention, health education, and promotion, he said, and it strives to provide health care that is appropriate, accessible, and sustainable, since Grenada is a small island with a fragile ecosystem. In answer to a question, he said that, “by and large, Grenada practices socialized health care,” in the sense that any individual can receive basic treatment at no cost. There is also private health insurance available, and individuals with resources may elect to pay for additional care in the private sector.

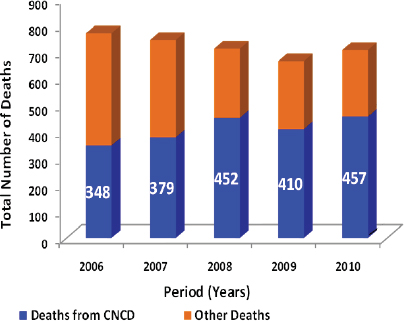

Hospital data are the primary source of information about disease in Grenada, Martin said, because the nation does not currently have the capacity to collect other sorts of health data. According to patient discharge data, from 2001 to 2010 there was a steady increase in the total number of hospital stays in Grenada while the percentage of hospital stays attributable to chronic diseases has increased from 18 percent to almost a third. Data on hospital deaths from 2006 to 2010 also indicate that chronic diseases had an increasing toll (Figure 2-1). By 2010, 65 percent of hospital deaths had complications from chronic diseases. Cardiovascular disease accounted for 37 percent of all chronic disease hospital deaths for the period from 2006-2010, while hypertension accounted for 26 percent, diabetes for 21 percent, and other chronic diseases for 16 percent. Cardiovascular-related deaths have increased since 2006, and diabetes deaths have increased even more sharply in that period of time. These data demonstrate a disturbing trend, Martin said.

The primary reason for the trend in Grenada, as elsewhere, Martin explained, has been an increase in tobacco use. Other factors include reduced physical activity, changes in diet, and increases in alcohol use, all of which are associated, he noted, with the rising socioeconomic conditions of many Grenadians. In Grenada, he said, health status and outcomes are actually worse for middle- and upper-income people than for those with the lowest incomes—which is the opposite of the pattern in many developed nations.

Grenada has a number of efforts in place to control chronic diseases:

FIGURE 2-1 Deaths in Grenada, 2006-2010 (population just over 100,000).

NOTE: CNCD = chronic noncommunicable diseases.

SOURCE: Martin (2011).

• The National Chronic Disease Non-Communicable Disease Commission, established in 2010, brings together multiple sectors, including agriculture, education, and trade, along with experts from a range of disciplines, to advise the health ministry regarding chronic disease policies.

• The newly launched Primary Health Care Renewal program is designed to support integrative primary health care and to decentralize decision making. District health care teams provide technical support for disease prevention programs developed at the local level. These multidisciplinary teams will not only include doctors and nurses, but will also “involve people like dentists, environmental officers, social workers, mental health workers, psychologists, educators, and nutritionists.”

• A National Tobacco Committee is developing legislation and other efforts to reduce tobacco use.

Other public health efforts include social marketing, such as television advertisements reminding viewers to have their blood pressure checked; public–private partnerships, such as a program to allow Grenadians to use exercise facilities belonging to the military; and health fairs and exercise programs sponsored by churches, private companies, and other organizations. Grenadians now also have Chronic Care Passports, which were designed to help to coordinate the care they receive at all levels of the system. These booklets contain demographic data, and patients are asked to carry them to every visit with a health care professional. The health care professional then can enter a record of the care delivered on the patient’s passport.

There are barriers to care and prevention of chronic diseases in Grenada, however, Martin said. There are gaps in surveillance and data analysis, and few of the data that are collected are used to develop policies, he observed. The health ministry has no health economist on staff, and the ministry has not been able to use economic tools to identify the costs of disease burdens and support planning and decision making. Indeed, the health care system actually lacks sufficient computers for such analysis, Martin said, noting that he often receives data in hard copy. Grenada also lacks a disease registry, which would provide a mechanism for sustaining social participation in health issues and public information. The nation lacks a tradition of public health research, and it lacks both human and financial resources for improved integration of health services.

At the same time, Martin added, Grenada has certain strengths and opportunities. The country has an excellent network of health care facilities, despite challenges with infrastructure. The progress these facilities have made in integrating primary health care leaves them well set up to move forward, Martin emphasized. Immunization coverage is 90 percent and the maternal mortality rate is almost 0. The country is politically stable and has the political will to improve in the area of health. The minister of health is “more excited about integrated primary health care than any minister had ever been in the history of Grenada,” Martin said, and “we have very strong affiliations with international agencies.”

Looking forward, Martin concluded that the key players who can help guide progress in Grenada—the government, the general public, the National Chronic Non-Communicable Disease Commission, the Diabetic Association, nongovernmental organizations and regional and international donors—are in place and have begun to focus on Grenada’s needs. Guidelines from the Pan American Health Organization and the WHO shape regional policy, and Grenadian officials tweak and give final approval to policies and program implementation, he said, pointing to that process as a place to look for improvement. “We have the determination to move forward with chronic disease control,” he added. “What we need is just good collaboration, integration, and help from wherever we can get it.”

KENYA

As in Grenada, health is viewed as a basic human right in Kenya, said Dr. Gerald Yonga, chair and associate professor of medicine and cardiology at Aga Khan University, who presented on behalf of Kenya’s director of medical services, Francis Kimani. The right to health is explicitly established in the new Kenyan constitution adopted in 2010. The Kenyan parliament is now working to implement the constitution and put in place policies that will make health care more accessible, and chronic disease control advocates are struggling to get attention during the process.

The new constitution divides the country into states that each have considerable autonomy. Kenya’s population of 42 million people is made up of approximately 42 different communities, or tribes, who speak different languages and have “slightly different cultures, interests, diets, and exercise habits,” Yonga explained. Kenya is a very capitalistic society with quite liberal markets. The country has “enormous” gaps between rich and poor, Yonga added, and it is home to both some of the richest people in the world and some of the poorest. The Kenyan gross domestic product (GDP) is $20.6 billion in U.S. dollars, Yonga said, and Kenya is the world’s 17th poorest country with an average annual per capita income of $780 (U.S.). Of the 42 million members of the Kenyan population, 78 percent live in rural areas, and 47 percent live below the national poverty line. The average life expectancy is 59.5 years. Annual per capita spending on health care is $27, and just 5.2 percent of government spending is on health.

The health care infrastructure, which is made up of public (44 percent), private, and religious facilities, is stretched thin, Yonga said. For every 1,000 people, there are 1.4 hospital beds, 0.14 physicians, and 1.18 nurses. Most of the health care resources are devoted to outpatient (39.6 percent) and inpatient (29.8 percent) care and health administrators (14.5 percent), and only 11.8 percent is spent on preventive care and public health programs. Only about 8 percent of Kenyans have health insurance, so the majority of the 39.3 percent of health care costs that come from the private sector are paid by individuals. Donors pay for 31 percent—a figure that has increased from 18 percent in the last 10 years, primarily due to funding for HIV programs. Of the remaining health costs, 29.3 percent are publicly funded, with 0.4 percent paid for by other sources.

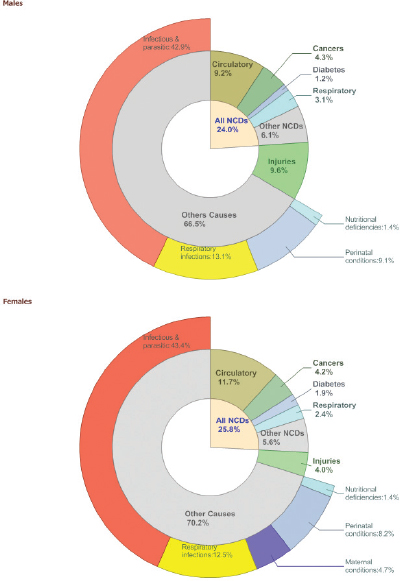

Kenya has a “double burden” of disease, Yonga noted. Communicable diseases, such as malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis, are not completely under control, but the rates of noncommunicable diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, cancer, chronic injury, and neurological and psychiatric disease, have been increasing for the past two decades. As can be seen in Figure 2-2, which shows deaths caused by different sorts of diseases in 2004 for males and females, the noncommunicable chronic diseases accounted for

FIGURE 2-2 Estimated proportional mortality, Kenya, 2004.

SOURCE: WHO (2008b).

approximately 22 percent of deaths for both sexes. The primary cause of chronic morbidity, Yonga said, is accidents, particularly automobile accidents; but chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and asthma also account for significant amounts of chronic morbidity as measured in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The toll of these different factors is shown in Table 2-1.

These data are suggestive of the significant burden of chronic diseases in Kenya, Yonga indicated, but they do not come from national surveys with good sampling methods. Regional health data are collected, but sampling and collection methods vary. Nevertheless, one overall trend is clear: early in the 20th century, health officials noted that Kenya had virtually no cardiovascular disease, and as late as the 1960s some communities in the country were called “low-pressure communities,” Yonga explained, because people’s blood pressure did not rise with age, regardless of what they ate. Researchers have shown that, over time, people have migrated from rural areas to urban areas and changed both their dietary habits and levels of physical activity, with predictable effects on body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, and other health indicators and outcomes. In general, the common risk factors that contribute to chronic diseases in Kenya are the familiar ones: tobacco use (which is rising among schoolchildren), alcohol consumption (which is much higher among males than females), inactivity (particularly in urban areas), and diet and obesity (there are disparities between urban and rural areas in both).

Numerous stakeholders play a role in the Kenyan health system, Yonga said, including the government, nongovernmental organizations, universities and research institutions, civil society, religious organizations, and the private sector. The government has taken a number of actions in response to noncommunicable chronic diseases, including the formation of a division to address them in 2001 (although Yonga said the division is grossly under-

|

TABLE 2-1 Chronic Disease Morbidity in Kenya, 2009 |

||

| Chronic Disease | DALYsa/1,000 capita/year | World Range |

| Other Unintentional Injuries | 6.8 | 0.6-30 |

| Traffic Accidents | 3.6 | 0.3-15 |

| Cardiovascular | 1.9 | 1.4-14 |

| Cancer | 1.9 | 0.3-4.1 |

| Asthma | 1.7 | 0.3-2.8 |

| Neuropsychiatric | 1.7 | 1.4-3.0 |

| Musculoskeletal | 0.6 | 0.5-1.5 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 0.6 | 0.0-4.6 |

a Disability-adjusted life year.

SOURCE: WHO (2009).

staffed and underfunded); bills to control tobacco and alcohol use in 2008 and 2010, respectively; the development of new plans and frameworks, which is currently under way; and the definition of health as a basic human right in the 2010 constitution. Several agencies collect data regularly: the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, which, because of funding limitations, provides only limited health information;1 the Kenya National Health Accounts, which tracks expenditures; and the Kenya Central Bureau of Statistics, which collects vital statistics.

There is currently an effort under way to broaden understanding of the significance of the chronic disease burden and to help the various stakeholders work together to develop an integrated policy on these diseases, Yonga said. A number of related efforts are already playing a role, he added, including a National Cancer Prevention program, strategic plans to combat diabetes and hypertension, and the national health policy framework, which is in development. Some research is ongoing, and some programs have been designed to raise awareness of risk factors and also to provide screening for several conditions. These and other programs have done well, Yonga observed, but they are, “unfortunately, uncoordinated. They need to be brought together in one framework,” he said.

The lack of coordination, and the lack of a national policy, are perhaps the most significant gaps in Kenya’s approach to chronic diseases, Yonga said. Funding is very limited. Furthermore, he said, “We are currently operating in lots of silos. We have many organizations within the ministry of health—especially donor-funded organizations—with completely different funding and infrastructure, and, often, a total refusal by particular departments to collaborate with others.” Recently, more attention has been paid to coordination and collaboration, but there are many obstacles, he said. One is the lack of primary care throughout Kenya. “Health care is free, yes, but, you pay nothing, you get nothing.” For example, he said such basic care standards as taking a patient’s blood pressure, height, and weight are not uniformly adhered to. A workshop participant added that many facilities lack sufficient operable equipment, such as calibrated instruments, and do not offer adequate training for staff in how and when to use these tools. In addition, there are no cost-effective models for screening and intervention, Yonga said. He added that the health information and surveillance system is “nonexistent,” although funding was recently secured for an attempt to develop an electronic health system as part of a government-wide effort to adopt electronic data collection.

In short, Yonga said, Kenya’s principal barriers to a more robust response to chronic diseases are

____________

1 For example, Yonga explained in answer to a question, this system does not track rates of diabetes.

• lack of national data on the economics of these diseases and the costs of specific interventions;

• competing priorities, especially the control of noncommunicable diseases being seen as competing with the control of communicable diseases;

• lack of political will to focus on chronic diseases;

• lack of policies and legislation that would facilitate disease mitigation; and

• insufficient resources and infrastructure for chronic disease reduction efforts.

Government action in Kenya usually begins with a body of data sufficiently persuasive to motivate the relevant ministry to draft policies for the cabinet, and then parliament, to consider. Persuading officials at each level to act requires hard data, Yonga emphasized, and the budget-allocation process depends not only on economic and other data but also on historical precedents for funding. “If historically you have been underfunded, you shall continue to be underfunded until you are able to prove that you really exist—and that is really the problem at the moment,” he said.

Yonga closed with his vision for chronic disease reduction in Kenya. The nation, he hopes, will develop an integrated and coordinated national policy that provides support of public education and promotion of healthy behavior and implements cost-effective screening and intervention programs at the community level and at health institutions. A strengthened primary care system will provide preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative care at all levels. And a strengthened health information and surveillance system will build the basic understanding of the disease burden and promote research on prevention and treatment. A sustainable funding mechanism, Yonga emphasized, will ensure the stability of this approach.

BANGLADESH

Bangladesh faces many challenges, said Shah Monir Hossain, a consultant to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and former director general for health services. In 2009, the country had a population of 162 million, and its population density is the highest in the world. Natural disasters in this low-lying nation frequently cause loss of life, assets, and infrastructure on a sweeping scale. Life expectancy at birth is 67 years (UNICEF, 2010). Nevertheless, the country has made steady improvements in many areas, Hossain said. For example, the 2010 poverty rate of 31.5 percent was down from 40 percent in 2005 (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2011). Between 1990 and 2010, the country reduced rates of measles,

mumps, and rubella, and 75 percent of children in Bangladesh are now fully immunized (Bangladesh Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2007).

Bangladesh faces a double burden of the infectious diseases common in developing nations plus a growing rate of chronic noncommunicable diseases attributable to social transitions that have brought rapid urbanization, unhealthy diets, and other risk factors. A 2010 national survey showed that 99 percent of the population had at least one risk factor for a chronic disease, and 29 percent had three or more risk factors. Chronic diseases now account for 61 percent of the total disease burden, and underprivileged rural and urban communities bear the heaviest burden of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, stroke, chronic respiratory diseases, and cancer. Cardiovascular disease (heart attack, stroke, and other) accounts for 12.5 percent of all deaths. Cancer claims 150,000 lives annually in Bangladesh, and more than 200,000 new cases are detected each year.

Bangladesh has a number of assets in the fight against these diseases, Hossain said. Health care facilities are widely available at the community level as well as for secondary and tertiary care; these facilities are overseen by a variety of agencies under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. There are specialized and teaching hospitals at the tertiary level as well as district hospitals (and a few district-level teaching hospitals). For primary health care there is a sub-district system (the Upazila Health Complex) with each subdistrict covering approximately 200,000 people; a health and welfare program and dispensary that covers approximately 20,000 people in each center; and community clinics that each typically serve approximately 6,000 people.

There are, however, a number of gaps in Bangladesh’s capacity to control chronic diseases. The primary care system focuses primarily on communicable diseases and maternal and child health, and adequate care for chronic diseases is not generally available, Hossain said. These diseases are not given high priority in United Nations (UN) programs or by development partners, and medical personnel lack the skills and training to address them. There is a need for more complete surveillance and information related to the economic burden of these diseases, and coordination is lacking between the public and private services that are available. Hossain would like to see a greater policy emphasis on chronic diseases in Bangladesh, such as a strategy for improving nutrition. He suggested that if the health sector placed greater emphasis on chronic diseases, budget allocations for combating them would increase, which would make it possible to increase the skill level of medical workers in these areas.

The ministries of Health and Family Welfare, Local Government, Planning, and Finance all have a stake in health issues and a role in the decision-making process for health sector planning, Hossain said. Private and civil

society groups, such as the Diabetic Association of Bangladesh and the National Heart Foundation, also play a role, as do development partners including the World Bank, WHO, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the UN Population Fund (UNFPA). While noncommunicable diseases were not a priority area in previous health sector programs, he noted, Bangladesh’s latest health sector program (2011-2016) includes an operational plan for the prevention, management, and control of non-communicable chronic diseases among its objectives, which should bring greater attention and support to the problem in Bangladesh. Specifically, the plan is designed to

• develop and implement effective, integrated, sustainable, and evidence-based public policies on chronic diseases;

• strengthen surveillance capacity for chronic diseases, their consequences, risk factors, and the impact of interventions;

• promote social and economic conditions that empower people to adopt healthier behaviors; and

• strengthen the health system’s capacity to manage chronic diseases and their risk factors.

The plan addresses not only conventional chronic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease and diabetes) but also road safety, injury prevention, and violence against women. It also addresses occupational safety and health; climate change, water, sanitation, and other environmental health issues; emergency preparedness and response; and mental health and substance abuse.

This effort will be supplemented by the Non-communicable Diseases Forum, an organization that works to reduce the burden of chronic diseases in Bangladesh by coordinating the efforts and resources of public and private health care providers and other partners such as nongovernmental organizations.2 The organization, which began its work in 2009, hopes to build awareness of these diseases, establish a database to coordinate information, and advocate for stronger policies related to chronic diseases. Hossain believes that with better information about the chronic disease burden, policy makers will put a higher priority on them and will provide more resources for fighting them.

____________

2 For more information about this organization, see http://ncdf.eminence-bd.org/ (accessed October 2011).

RWANDA

In Rwanda, as in other very-low-income countries, communicable diseases, high rates of maternal death in childbirth, deaths of children under age 5, and other conditions still take a heavy toll. Nonetheless, chronic diseases account for approximately 25 percent of the disease burden, said Gene Bukhman, senior technical advisor on noncommunicable disease at the Rwandan Ministry of Health.

Rwanda, Bukhman said, has made “absolutely extraordinary” progress in improving its health system since 1994, when the country was, in effect, “starting from scratch.” The mortality rate for children under 5 has decreased dramatically from 200 deaths per 1,000 people annually to fewer than 80. There has been a large increase in the percentage of women who deliver their babies in a health facility, rates of malnutrition have decreased, and there is universal coverage for HIV, Bukhman added. Rwanda provides an excellent demonstration of how leadership in the health sector can yield measurable improvements, he said, noting in particular the efforts of the current minister of health, Agnes Binagwaho, who oversaw the increase in HIV coverage.

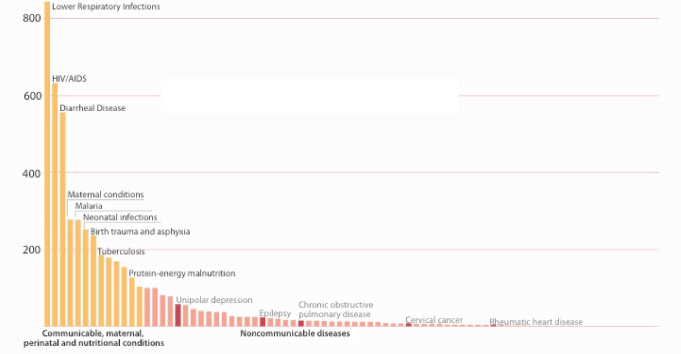

For Rwanda, Bukhman suggested, chronic diseases are an obvious next target for those involved in health planning. These diseases are very visible and in many cases preventable, and the rescue principle—the duty to alleviate suffering where it is possible to do so—makes them an important priority. The challenge, however, is that no single chronic disease is dominant in terms of prevalence, as Figure 2-3 illustrates. Hospital data indicate that in Rwanda these diseases account, in total, for only about 10 to 15 percent of hospital admissions and 20 to 26 percent of deaths, he added. On the other hand, Bukhman noted, they require much longer hospitalization times so their burden on the health system is high.

Another challenge, Bukhman observed, is that in Rwanda the major causes of these diseases are probably not the four major risk factors that are at work elsewhere: tobacco, lack of physical activity, obesity, and alcohol. For example, he said, virtually none of the cancers seen in Rwanda are caused by tobacco. Instead, viral infections, streptococcal disease, and household air pollution are the primary risk factors for heart and renal disease and other conditions. Collecting data on individual conditions in Rwanda is challenging, Bukhman said, because if considered each by itself, the conditions are often rare. Rheumatic heart disease, for example, has a prevalence of just 0.2 or 0.3 percent. While it is important to seek data on such traditional risk factors as smoking and BMI rates, Bukhman said, it is also important to recognize that in Rwanda the noncommunicable diseases are affecting children and young adults and that they are not caused by the risk factors of affluence but rather by many of the same factors that are

FIGURE 2-3 The long tail of endemic noncommunicable diseases in Rwanda.

SOURCE: Bukhman (2011).

associated with the “major killers,” the communicable diseases. Table 2-2 shows a number of factors linked to poverty that influence noncommunicable diseases in Rwanda.

Rwanda is known for its centralized, coordinated planning on health issues, Bukhman said, and health leaders held a summit in January 2010, with the goal of building partnerships to tackle noncommunicable diseases. A wide range of groups worked to identify national priorities based on experience in particular districts—participants included Rwandan facilities and associations focused on particular diseases; Rwandan government; regional and international universities; and such international partners as WHO, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Clinton Health Access Initiative. The group recognized that new strategies were needed to address the gaps in Rwanda’s health services for noncommunicable diseases. An obvious first goal, Bukhman said, was to decentralize services for chronic diseases and incorporate more care related to chronic diseases at the community and district levels. The group also determined that there was a shortage of qualified personnel to provide acute care at the district level, and they agreed that a consortium of medical centers in the United States should support residency programs for district-level and family-practice physicians. Other needs identified included pathology services, cardiac surgery, and cancer services, all of which will require additional funding.

Yet another need, Bukhman said, is the planning and training required to enable Rwanda’s medical system to absorb the enormous amounts of money needed to improve services—assuming that money can be made available. Absorbing new funds at a rate of $1 or $2 per capita would probably be manageable, he said, but more than that would be beyond the system’s capacity. Furthermore, it will take time for new guidelines and protocols to go through the process of development and field testing so that they can be properly implemented to meet local needs.

In conclusion, Bukhman observed that “these are not emerging diseases; they have been endemic in [low-income] countries since the 1950s.” What is happening now, he said, is a return to higher expectations for the health system, and “an opportunity for the current generation to deliver on that.”

KERALA, INDIA

India is the largest democracy in the world in terms of population, noted Meenu Hariharan, director and chief executive officer of the Indian Institute of Diabetes and state nodal officer of the National Program for the Prevention and Control of Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke. It

TABLE 2-2 Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in Rwanda Linked to Conditions of Poverty

|

|

||

| Condition |

Risk Factors Related to Poverty |

|

|

|

||

| Hematology and oncology |

Cervical cancer, gastric cancer, lymphomas, Kaposi sarcoma, hepatocellular carcinoma |

HPV, H. pylori, EBV, HIV, hepatitis B |

|

Breast cancer, CML Hyperreactive malarial splenomegaly, hemoglobinopathies |

Idiopathic, treatment gap Malaria |

|

| Psychiatric |

Depression, psychosis, somatoform disorders Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder |

War, untreated chronic diseases, undernutrition Idiopathic, treatment gap |

| Neurological | Epilepsy Stroke |

Meningitis, malaria Rheumatic mitral stenosis, endocarditis, malaria, HIV |

| Cardiovascular |

Hypertension Pericardial disease Rheumatic valvular disease Cardiomyopathies Congenital heart disease |

Idiopathic, treatment gap Tuberculosis Streptococcal diseases HIV, other viruses, pregnancy Maternal rubella, micronutrient deficiency, idiopathic, treatment gap |

| Respiratory | Chronic pulmonary disease |

Indoor air pollution, tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, treatment gap |

| Renal | Chronic kidney disease | Streptococcal disease |

| Endocrine |

Diabetes Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism |

Undernutrition Iodine deficiency |

| Musculoskeletal | Chronic osteomyelitis |

Bacterial infection, tuberculosis |

| Musculoskeletal injury | Trauma | |

| Vision |

Cataracts Refractory error |

Idiopathic, treatment gap Idiopathic, treatment gap |

| Dental | Caries | Hygiene, treatment gap |

|

|

||

NOTE: CML = chronic myeloid leukemia; EBV = Epstein-Barr virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HPV = human papillomavirus.

SOURCE: Kidder et al. (2011).

is a complex country, with 28 states and 7 union territories.3 As one workshop participant emphasized, the country has many cultural and linguistic traditions, and it is necessary to factor those into any kind of national planning. The union governments have considerable health-related responsibilities, including policy making and controlling drug standards. Health care services are delivered through a multi-level structure, which includes

• sub–health centers that offer trained health care workers (not doctors) to cover populations of 3,000 to 5,000;

• primary health centers, headed by medical officers, which each supervise six to eight sub–health centers and thus serve 20,000 to 30,000 people;

• community health centers, which are the first layer that provides inpatient services. These each have 30 to 50 beds and provide basic specialties for populations of 80,000 to 120,000;

• district hospitals that provide multiple specialties; and

• medical colleges that offer tertiary-level hospitals.

Hariharan focused on the small, very densely populated state of Kerala, which is known for high literacy rates, social activism and reform, and a high-quality health care system. The backbone of Kerala’s health care system, she explained, is the care provided at the local levels—most often by paramedics rather than doctors. Table 2-3 provides some basic indicators for contrasting Kerala with the whole of India and, for comparative purposes, with Sweden.

As India has become more prosperous, Hariharan said, it has experienced the same changes that have affected other countries and contributed to increases in chronic diseases: unhealthy diets, smoking, physical inactivity, and alcohol abuse. Kerala is no exception—India has been described as the diabetes capital of the world and Kerala, with a diabetes rate of 19.5 percent, as the diabetes capital of India. Other noncommunicable diseases have similarly high rates of prevalence: 36.1 percent for hypertension, 85.6 percent for central obesity, 24 percent for adolescent obesity, and 20 percent for coronary heart disease. Kerala also has a very high suicide rate, particularly for males (44.7 per 100,000 people, as compared to 26.8 for females), which Hariharan attributed to economic struggles. Rates of smoking are also high among men (28 percent compared to 0.4 percent for women) and college students (11.7 percent), and the lung cancer rate is 8.1 percent.4

____________

3 Each state has an elected government. The union territories are governed by presidentially-appointed administrators.

4 Hariharan noted that some of these data are old and that smoking rates may have been declining somewhat, though tobacco chewing and oral cancers have been increasing.

TABLE 2-3 Basic Indicators for Kerala, India, and Sweden

| Indicator | Kerala | India | Sweden |

|

Population |

33 million |

1030 million |

9 million |

|

Death rate (per 1,000 people) |

6.8 (SRS 2007a) |

7.4 (SRS 2007) |

10 |

|

Infant mortality rate (per 1,000 people) |

13 (SRS 2007) |

55 (SRS 2007) |

6 |

|

Institutional delivery |

99% (NFHS3b) |

39% (NFHS3) |

100% |

|

Birth rate (per 1,000 people) |

14.7 (SRS 2007) |

23.1 (SRS 2007) |

11.7 |

|

Female literacy |

87.9% |

45.16% |

100% |

|

Maternal mortality rate (per 1,000) |

81 |

212 |

8 |

|

Sex ratio |

1058 |

933 |

980 |

|

Immunization coverage |

87.9% (CES 06c) |

42% (NFHS3) |

100% |

|

Human Development Index (out of 1) |

0.62 |

0.47 |

0.94 (1st in world) |

aSample Registration System Bulletins, Office of the Registrar General & Census commissioner, India.

bNational Family Health Survey, India.

cCoverage Evaluation Survey, All India Report 2006, UNICEF.

SOURCE: Hariharan (2011).

In 2008, India launched a national program to combat diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and stroke, called Health in Your Hands. The program focuses on community-based detection and awareness camps, workplace interventions, and school programs designed to build awareness of lifestyle diseases, as well as on subspecialty clinics for the treatment of patients. Hariharan offered several lessons from the implementation of this program in Kerala. As is the case with other low-income countries, India has the double burden of infectious disease and noncommunicable ones. Leprosy, malaria, and other diseases are largely under control, but newer ones such as hepatitis, hemolytic fevers, H1N1, and leptospirosis have brought a new burden—and perhaps taken some attention away from chronic diseases. Moreover, many communicable diseases leave behind lasting health problems, such as arthritis and musculoskeletal deformities, that may have long-term economic consequences for families. Malnutrition is also still a problem in many places, and it causes many Indians, particularly children, to be more vulnerable to disease. These problems are very present in Kerala.

In addition to competing with these various issues for attention, the Health in Your Hands program was also hampered by limited capacity for screening and surveillance of chronic diseases, Hariharan said. The private sector plays little role in surveillance in India and, at the district level in particular, there is limited capacity to analyze data and respond to data

findings. Other national programs provided some assistance that strengthened Health in Your Hands. For example, the National Rural Health Mission provided both money and trained medical workers; and the integrated Child Development Services Scheme provided support for children, including health education and nutritional supplements. Public–private partnerships are also very important in Kerala, Hariharan added, because there are many private facilities in the state.

Looking forward, Hariharan indicated that bridging gaps and inequities in care will be a primary goal in Kerala. “We boast of a good health infrastructure but it is at times absolutely unequally distributed,” she said. She believes that the key strategies for addressing this problem will be reducing costs and improving efficiency, decentralizing regulation, improving information sharing, improving basic facilities such as laboratories, and building the skills of health workers at the community level. At present there is not a robust health insurance system in India, and private facilities are often of higher quality than public ones. There are few regulations on providers, premiums are unaffordable for many people, and exclusions and administrative procedures complicate the process, she noted.

In response to a question, Hariharan said that as a national program is implemented it is very important that regional services be coordinated through the main health services department. “You identify the centers to which you want to coordinate—smaller units of local self government. You have to educate them, to make them understand why you are doing this. The main network goes down through the community health centers.”

For Hariharan, the primary conclusion from a regional perspective is “You cannot depend only on the government, only on society, or only on a single community.” A multipronged approach to preventing chronic diseases is needed, one that involves a strong public health policy at the national level (to focus on changing personal behavior and improving the environment for healthy life choices); strong community-based programs; and clinical preventive services.

CHILE

Chile began a major reform of its health care system in 2006. The experience of this reform serves as an example and offers a number of lessons learned from a health decision-making and priority-setting process, which was inclusive of, although not limited to, chronic disease services. The reform was in response to a broad set of problems, said Antonio Infante, Chile’s former undersecretary for health. There had been serious inequities in the delivery of care, he explained. Epidemiological changes had altered the disease burden, and there was a need to greatly increase the efficiency with which resources were used. Perhaps most important, he added, was the dissatisfaction of Chile’s citizens with their health care.

Chronic, noncommunicable diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, are the majority of the disease burden in Chile, accounting for 76 percent in 2007. For most of these conditions, it is the lower-income, less-educated people who are most likely to have problems, he said. For example, those in the lowest educational category have three times more cardiovascular disease than those in the highest education group, and they are roughly twice as likely to be obese or have diabetes.

Chile has a national health service that was modeled after the one in the United Kingdom. It is used primarily by lower-income Chileans, Infante said, while affluent Chileans use private insurance. While 73.5 percent of all Chileans use the public system, fewer than 40 percent of the wealthiest quintile do so. The 2006 reform was designed to address this imbalance by providing a plan that bridged the two systems.

At an annual cost of $130 per capita, the plan was designed to cover 60 percent of the burden of disease, Infante said. Its goal was to focus on the highest-priority medical problems, to offer guaranteed limitations on out-of-pocket expenses, and to provide high-quality care by certified medical professionals. The plan developers used surveys to identify Chileans’ views of their highest-priority (most frequent, severe, and expensive) medical concerns. They then assessed the epidemiological impact of these concerns, the cost effectiveness of available treatments, and the system’s capacity to provide the requisite care throughout the country. Despite controversy, the developers settled on 56 conditions for which the plan would guarantee care (the number is now 69) and developed clinical guides with explicit protocols for physicians to follow.5

The guides were voluntary, Infante said, but the College of Physicians still objected to this limitation on their autonomy. Others objected that the plan did not provide universal coverage and was difficult for ordinary people to understand. Ads were posted in opposition to the reform, some going so far as to state that the new plan put citizens’ jobs at risk. Nevertheless, the plan has been implemented, and initial impacts are now evident. Perhaps most important, in Infante’s view, is the financial protection the plan provides. “People are so afraid of being ill,” he said, “that having the guarantee [of care] is a very important thing for families.” Overall, the guaranteed care made people feel more confident. The program has also led to a reduction in high blood pressure, mostly due to wider coverage for primary care, Infante said.

In Infante’s view, the system still needs to address a number of problems. Inherent in the process of prioritization is the pressure put on the

____________

5 In answer to a question, Infante explained that for care that is very expensive, such as transplants, there is a commission that reviews the evidence base, the patient’s prognosis, and other factors, and makes a recommendation.

decision makers by different industries, societies, and advocacy groups. In order to resist these pressures, the government will need to become more confident in the decision-making process. The program will also have to address the large inequities that still do exist even after its implementation. In addition, progress is not yet evident in such lifestyle changes as reducing consumption of salt, tobacco, and alcohol or increasing physical activity, and the program has not yet helped to control diabetes. The new system also needs to address long wait times for care and medical problems not on the list of 69 conditions for which care is guaranteed. “We need a stronger primary health care [system],” Infante said, and for success in that area, “we need the support of physicians and the physician union.”

SUMMATION

The six presentations illustrated the variation in the challenges related to chronic diseases across low- and middle-income countries. The presentations showed how economic, political, cultural, and health systems factors can affect a country’s progress toward addressing chronic diseases at the national and subnational level. There were, however, a number of common threads that emerged across these diverse presentations. Insufficient national-level data and surveillance capacity was a common theme. Countries had developed different strategies to fill these gaps in their national-level data, such as the use of hospital data, small-scale surveys, research studies, and regional data from similar countries. Another common theme was the lack of economic data and economic analyses, which are important for informing policy decisions and making compelling arguments for resource allocation. The lack of resources and capacity across all aspects of the systems and areas of expertise required to manage chronic disease also complicate efforts to advocate for policies and programs. This lack of resources and capacity is especially challenging when countries face the double burden of communicable and chronic diseases.

Several countries also faced difficulties garnering political will for action on chronic disease. Where there had been recognition of the need to address chronic diseases, several speakers described the challenge of a lack of coordination among existing efforts and the challenge of making the transition from idea to sustained action. For example, speakers discussed national plans for non-communicable disease control that have not been fully implemented and external projects that left behind little support for sustaining their efforts after their research was completed or programs were initiated.

Chapter 6 provides a more complete summary of the considerations raised in this session along with the presentations and discussions throughout the workshop.

This page intentionally left blank.