3

Transitional Care and Beyond

During the second session of the workshop, speakers discussed topics related to providing care for people before, during, and after hospital discharge. They explored the current and potential roles of registered dietitians in hospitals, a multidisciplinary approach to discharge, and home- and community-based services. Hospitalization is common among older adults and they are being discharged sicker than in the past said Nadine Sahyoun, associate professor of nutrition epidemiology at the University of Maryland in College Park, who moderated the session. Transitional care models “follow patients across settings, improve coordination among health care providers, and also help individuals better understand their posthospital care,” she said. Nutrition services are an important element of transitional care and recovery to ensure that older adults in their homes are well nourished.

ROLE OF NUTRITION IN HOSPITAL DISCHARGE PLANNING:

CURRENT AND POTENTIAL CONTRIBUTION OF THE DIETITIAN

Charlene Compher, associate professor of nutrition science at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, drew on her experiences in a hospital setting at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) as context for her presentation. HUP is rated among the top 10 hospitals in the United States, providing trauma, cancer, transplant, cardiac, and geriatric

care, yet only had 20 registered dietitians (RDs) to provide nutritional care to the almost 800 patients per day and 42,500 admissions in fiscal year 2011. HUP has a 2014 goal of eliminating preventable deaths and 30-day readmissions, and achieving both requires all hospital employees, including RDs, to focus on the same goals.

The Role of RDs in Hospital Readmissions

In order to achieve its 2014 goal of eliminating 30-day readmissions, HUP will address the factors that predict hospital readmissions, such as those identified in Box 3-1.

There is a growing body of research demonstrating that dietitians can help prevent hospital readmission by providing nutrition counseling that changes patients’ behaviors and improves clinical outcomes. Studies have shown that RD counseling can result in weight loss (Raatz et al., 2008), improved weight management and lipid profiles (Gaetke et al., 2006; Welty et al., 2007), sustained heart-healthy diet modifications (Cook et al., 2006), and adherence to a low-sodium diet in patients with heart failure (Arcand et al., 2005). Implementation of recommendations for enteral tube feeding in long-term acute care facility patients resulted in shorter lengths of stay, improved albumin levels, and desired weight gain (Braga et al., 2006). Compher highlighted an “intriguing study” conducted by Feldblum and colleagues in Israel among adults age 65 years and older. Feldblum et al. (2011)

BOX 3-1

Factors that Predict Hospital Readmissions

Utilization Factors

• Longer length ot stay

• Prior admission(s) in the past year

• Previous emergency department visits

Patient Characteristics

• Comorbidity (diabetes mellltus. hypertension, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, depression)

• Living alone

• Discharged to home

• Medicare/Medicaid

SOURCE: Leas and Umscheid, 2011.

compared outcomes in a control group receiving the standard in-hospital screen or one visit by an RD to those in the intervention group receiving three home visits by an RD after discharge combined with indi vidualized nutrition assessment, enhanced food intake, and nutrition supplements, as needed. The intervention group scored better on nutritional assessments, experienced less frequent hypoalbuminemia, and had lower mortality rates when compared to the control group. However, Compher noted, results do not indicate if the improvements were due to the nutrition care received in the hospital or the RD visits after discharge, so the results are attributed to both.

The Role of RDs in Current Hospital Nutrition Practice

As required by the Joint Commission, nutrition screening at HUP is completed within 24 hours of hospital admission. A nurse usually completes the screening, which includes individual institutional criteria such as unexpected weight gain or loss, gastrointestinal symptoms, obvious emaciation, pressure ulcers, and home feeding by intravenous or tube route. Patients identified as high risk are referred to an RD for a full nutrition assessment. This assessment, which is more complex and may take more than an hour to complete, includes

• diet history,

• weight history,

• medical history,

• medication profile,

• laboratory values,

• current conditions, and

• physical examination for nutrient deficiency or excess.

Once the assessment is completed, a nutrition care plan is developed and the patient’s nutrition risk level is set to establish a follow-up schedule.

RDs also conduct nutrition assessments on people referred by physicians, admitted with a high-risk diagnosis or condition (e.g., receiving care in the intensive care unit), and receiving monitored nutrition support therapy. RDs provide instructions for people being discharged with home tube feeding and parenteral nutrition support, take part in discharge planning rounds, and communicate with RDs in outpatient care centers. Compher remarked that, while it would be ideal to provide nutrition assessment to all patients, the process is time consuming, hospitals have inadequate RD staff, hospital stays are too short, and hospitals’ limited resources are used on patients for whom nutrition interventions will provide the best outcomes.

Potential Future RD Roles

Compher suggested that, despite limited time and resources, there are at least three opportunities to improve the ways RDs are involved in preventing hospital readmissions:

1. Ensure that nutrition assessment goals are included in discharge plans. Through the use of electronic medical records, patients’ nutrition assessment goals and information could be transmitted directly to their discharge plans. This may assist discharge planners in making the appropriate referrals. Ideally, RDs would be included on the discharge planning team to review hospital records for nutrition care plans that require home support, identify people whose nutrition status has changed and who require increased care, and communicate with staff at outside facilities that provide postdischarge care.

2. Increase cases receiving nutrition assessments. Compher acknowledged that hospitals may not have the staff, funding, or time to increase the number of people screened and assessed. She suggested using dietetic technicians to conduct the screenings and referrals and to focus on those people most likely to be readmitted, including everyone 65 years and older and patients admitted through the emergency room. She also suggested that dietitians screen patients in the emergency department in order to begin nutrition care early or to identify patients in need of nutrition services although not being admitted and make the necessary referrals.

3. Improve integration of hospital and post hospital nutrition care. Although achieving this goal requires more trained nutrition professionals in the community, it would be beneficial to have hospital RDs more involved in post hospital care. Compher proposed having RD positions in heart failure programs, all outpatient clinical programs, and community geriatric care programs. She also suggested paying RDs for home visits to conduct nutrition assessments and providing hospitals with financial incentives for avoiding readmissions.

Closing Comments

Compher concluded by noting the importance of moving from the current level of RD availability into a future with enhanced nutrition care for older adults. It may be daunting but it is imperative that the nutrition community “take the challenge” to prevent hospitals from discharging nutritionally compromised people who are more likely to be readmitted.

TRANSITIONAL CARE: A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

Eric Coleman, professor of medicine and head of the Division of Health Care Policy and Research at the University of Colorado at Denver, reiterated the importance of a team approach to providing transitional care, stressing that the most important teammate is the one receiving the care. The ultimate goal for transitional care is “to create a match between the individual’s care needs and his or her care setting.” Achieving that goal can reduce frequent and costly readmission rates; the Medicare 30-day hospital readmission rate is nearly 20 percent (AHRQ, 2007) and hospitals with high readmission rates are financially penalized under the Affordable Care Act.

The Role of Nutrition in Hospital Readmissions and Transitional Care

While nutrition plays a role in improving general health, the role of nutrition in hospital readmission remains unclear, Coleman said. There are studies linking the two but they mostly explore undernutrition, are observational, sometimes rely on clinical assessment or laboratory results, and rarely explore the role of supplementation (Friedmann et al., 1997). He noted that “the role of nutrition is likely entangled with chronic illness, frailty, [and] socioeconomic status.” Nutrition should not be used as a bartering tool in a hospital’s efforts to provide intervention in a patient’s home, cautioned Coleman. For example, in order to avoid financial penalties, hospitals are eager to intervene on high-risk older adults and may use nutrition services as an incentive to persuade them to agree to home visits.

The Role of the Patient in Transitional Care

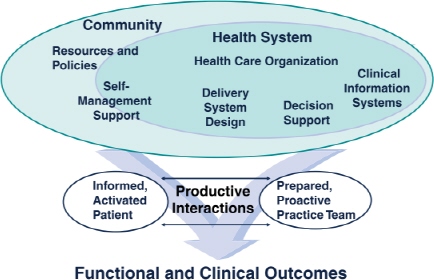

In order to determine how to improve the quality of transitional care, Coleman suggested talking to people receiving the services. He said they report feeling unprepared and unsure of what to do when they return home. They are confused because they receive conflicting advice from professionals in various health care settings, and they do not know who to contact to reconcile the discrepancies. Finally, they are frustrated because their family caregivers are left to complete tasks that the professionals left undone. Often people receiving transition services interact with their health care providers for only a few hours a week. Therefore, they, or their family members, end up acting as their own caregivers, making decisions without the skills, tools, or confidence to provide effective care. As shown in Ed Wagner’s Chronic Care Model (see Figure 3-1), an informed and active

FIGURE 3-1 Wagner’s Chronic Care Model.

SOURCE: Wagner, 1998. Reprinted, with permission, from the American College of Physicians.

patient is vital to achieving improved functional and clinical outcomes (Wagner, 1998; Wagner et al., 2001).

The Care Transitions Intervention™

The Care Transitions Intervention™ (CTI) is a low-cost, low-intensity intervention designed to build one’s skills and confidence and provide the necessary tools to encourage the patient to be an informed and active decision maker during care transitions (Coleman, 2011). The intervention consists of one home visit within 48–72 hours after discharge and three phone calls within 30 days. The patient’s “transition coach” models behavior for how to handle common problems, role-plays the next health care visit, elicits the patient’s health-related goals to be accomplished in the next 30 days, and creates a comprehensive medication list. Because the patients and caregivers are members of their own interdisciplinary team, they identify their own health care goals and the skills needed to coordinate their care across settings. The four areas that patients identified as those they need the most help with (referred to as the “four pillars”) are

1. development of a patient-centered health record,

2. assistance with medication self-management,

3. follow-up with primary care physician and specialists, and

4. knowledge of “red flags” or warning signs and symptoms and how to respond.

The patient-centered health record contains the patient’s current medical conditions, warning signs that relate to the patient’s condition, a list of medications and allergies, advance directives, and space for the patients to list their questions or concerns to discuss during their next health care visit. The transition coach initially meets with the patient prior to hospital discharge to introduce the program and patient-centered health record, establish rapport, and schedule the home visit. During the home visit, the patient indentifies a 30-day health-related goal; the coach reconciles the patient’s medications; and they role-play how to respond to red flags, obtain a timely follow-up appointment, and raise questions for health care providers during subsequent visits. The phone calls are conducted to follow up on active coaching issues, review the four pillars of the intervention, estimate the amount of progress being made, and ensure the patient’s needs are being met (Coleman, 2011).

CTI Key Findings and Next Steps

Results from the CTI showed that reductions in hospital readmission rates were significantly lower at 30 days postdischarge (the time period in which the transition was involved). Furthermore, significantly lower rates at 90 and 180 days postdischarge demonstrate the sustained effect of the coaching. The net cost savings for 350 patients over 12 months was $300,000. CTI has been adopted by 500 health care organizations in 38 states and resulted in reduced 30-, 60-, and 80-day readmission rates (Coleman et al., 2004; Crouse Hospital, 2008; Parry et al., 2006; Perloe et al., 2011). Preliminary data from evidence-based care transition grants from the Administration on Aging and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services show that 16 states are employing models to help older adults stay in their homes after discharge from hospitals, rehabilitation centers, or skilled nursing facilities, 11 of which are implementing CTI. In April 2011 up to $500 million was made available by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services under the Affordable Care Act Section 3026 to fund organizations to provide evidence-based transition care services to high-risk Medicare recipients (CMS, 2011).

Closing Remarks

Coleman concluding by summarizing the four factors that promote successful implementation of CTI: (1) model fidelity, (2) selection of an appropriate transition coach, (3) execution of the model, and (4) support to sustain the model. Successful implementation of CTI can reduce readmission rates by helping older adults and their caregivers become informed and active participants in their care transitions.

NUTRITION IN HOME- AND COMMUNITY-BASED SYSTEMS:

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE FIELD

Through her position at the Alabama Department of Senior Services, Bobbie Morris visits older adults in their homes and senior centers and learns about the nutrition services they are receiving. Services provided under the Older Americans Act (OAA) Elderly Nutrition Program aim to promote health, provide nutritious meals that meet current dietary guidelines and older adults’ needs, reduce social isolation, and link adults to social rehabilitative services through other home- and community-based long-term care organizations. Her experiences suggest that facilities that promote fun and physical activity in addition to the OAA services of meals, nutrition education, counseling, and screening and assessment may have higher rates of participation.

Services Provided Under Title III C of the OAA Nutrition Program

Under Title III C of the OAA Nutrition Programs, meals can be served through congregate or home-delivered services. Congregate nutrition services provide meals five or more days a week in a group setting, including adult daycare, whereas home-delivered meals are hot, cold, frozen, dried, canned, and supplemental foods that are distributed to adults’ homes. In both cases, nutrition education and counseling are provided to the recipients and, in the case of home-delivered meals, their caregivers (AoA, 2011a). The numbers of congregate, home-delivered, and total meals served through the OAA Nutrition Services program over the past 10 years are shown in Table 3-1.

As mentioned in a previous presentation, the number of home-delivered meals has increased over the years while the number of congregate meals has decreased, possibly indicative of the number of frail older adults staying in their homes, Morris said. She suggested that the decline in total meals

TABLE 3-1 Number of Meals Served Through OAA Nutrition Services in the United States

|

Number of Meals Served |

|||

| Fiscal Year | Home-Delivered Meals | Congregate Meals | Total Meals |

| 2000 | 143,804,683 | 116,016,249 | 259,820,932 |

| 2001 | 143,719,629 | 112,243,758 | 255,963,387 |

| 2002 | 141,958,732 | 108,333,836 | 250,292,568 |

| 2003 | 142,889,385 | 105,905,622 | 248,795,007 |

| 2004 | 143,163,389 | 105,606,162 | 248,769,551 |

| 2005 | 140,132,325 | 100,530,354 | 240,662,679 |

| 2006 | 140,212,524 | 98,031,661 | 238,244,185 |

| 2007 | 140,990,040 | 94,877,137 | 235,867,177 |

| 2008 | 146,897,367 | 94,196,192 | 241,093,559 |

| 2009 | 149,188,917 | 92,492,669 | 241,681,586 |

NOTE: Data include number of meals served in 50 states, District of Columbia, and U.S. territories.

SOURCE: Data from 2000–2004: AoA, 2009; data from 2005–2009: AoA, 2011b.

served is partially due to increases in fuel and food costs that exceed program funding increases.

Flexible Meals Services

Morris described several flexible meal services funded by a variety of sources. In some cases, meals may be offered at a range of locations and at various times during the day. Voucher programs provide participants with the option to go to a restaurant or grocery store and order a meal or purchase items that meet the required nutrition guidelines. In some areas where there are limited restaurants, hospital vouchers can be used to purchase a meal from a hospital cafeteria. In some areas, meals may also be offered at homeless shelters. Flexible meal packages include options for receiving more than one meal per day, such as a hot meal at lunch and a frozen meal for dinner, or shelf-stable meals for weekends, holidays, and emergencies.

Meals can be provided through local and statewide contracts, at on-site kitchens, and by shipments to participants’ homes. For example, a local contract could arrange for a community nursing home or restaurant to prepare and deliver meals to homebound adults or congregate meal facilities. Alabama has a statewide contract with Valley Food Service for preparation of all hot and frozen meals for the state. The benefit of a statewide contract is reduced meal costs; however, it also limits the variety of available foods and results in all state participants receiving the same meal.

Prioritizing Services

Despite the availability of Title III nutrition services and programs like Meals On Wheels, there are still people on waiting lists for meals. The OAA states that “services are targeted to those in greatest social and economic need with particular attention to low-income individuals, minority individuals, those in rural communities, those with limited English proficiency, and those at-risk of institutional care” (AoA, 2011a). In order to determine who is most in need of service, nutrition risk is assessed using tools such as the Nutrition Screening Initiative checklist (Posner et al., 1993) and the Mini Nutritional Assessment® (Nestlé Nutrition Institute, 2011; Vellas et al., 1999). Morris stressed the importance of properly training staff on how to administer the assessment tools to ensure that the questions are asked correctly and the appropriate information obtained. Other ways to determine who on the waiting list receives meals or to provide alternate services include

• decisions made by a Senior Center Advisory Board based on need;

• a first-come, first-served approach;

• sponsored meals provided by organizations such as churches, rotary clubs, and women’s clubs; and

• managing delivery routes to redirect meals intended for those who cancelled their meal service to be delivered to other people in the same area.

Closing Remarks

Morris closed by sharing her view that a “no wrong door” philosophy would provide seamless access to services regardless of how or where someone encounters the service system. She suggested that service programs and funding streams be brought together to ensure that older adults receive the information, referrals, and care they need. The long-term goal is for older adults to make informed choices for their long-term care, while reducing and controlling Medicaid spending, decreasing nursing home and institutional care, increasing availability of home- and community-based services, and reducing the number of people on waiting lists for nutrition services.

DISCUSSION

During the discussion, points raised by participants included the role of nutrition in transition services, the role of physicians in the referral process, and patients’ perception of needs during and after discharge.

Role of Nutrition in Transition Services

Nancy Wellman questioned why nutrition is not a larger component of transition services. Coleman noted that while nutrition was mentioned during his qualitative research, the focus of the CTI model is patient-identified goals, not those chosen by the health care provider, so nutrition will not be addressed if it is not one of the patient’s goals. Rose Ann DiMaria-Ghalili followed up by pointing out that none of the transitional care models published by the Remington Report included a nutrition component. She said this is “quite alarming” and believes nutrition screening should be conducted throughout the transitions. She also suggested that health care professions using various screening tools collaborate to ensure consistency, and nurses would be amenable to using whatever tool is recommended.

Role of Physicians in Referral Process

Jennifer Troyer referred to Compher’s statement that two-thirds of referrals to RDs for nutrition assessment were from physicians and wondered if it was the same physicians repeatedly making the referrals. Compher stated that it was a variety of physicians, possibly due to HUP’s role as a teaching hospital; residents make referrals following the lead of physicians they respect and continue to refer patients to RDs as they move up the tiered levels of training. Heather Keller asked why more people were not being referred to RDs as a result of the nutrition screening, and why physicians were making the majority of referrals. One-third of HUP’s beds are intensive care unit beds; therefore, referrals for those patients are more likely to come from a physician. Coleman noted that hospital stays are shorter and people may be discharged before laboratory results from the nutrition evaluation indicating nutrition problems are received. He said, “if we’re going to pursue these evaluations, it’s also worth thinking about the workflow, about what happens when the lab comes back abnormal and the person left 24–48 hours ago.”

The Patient’s Perception of Need During and Postdischarge

James Hester asked about the panelists’ experiences understanding patients’ perceptions of their needs during discharge and postdischarge, including their receptivity to their nutritional needs. Compher noted that based on her personal experience individuals who are being discharged from the hospital want more than anything to be home and in a situation they understand and can control. Coleman agreed that individuals tend to feel inundated while in the hospital, and suggested letting them get settled in their homes and then addressing some of the issues several weeks later, when they may be more prepared to think about them. Sahyoun added

that individuals may have support from their family and friends the first few days after discharge but then there is an adjustment period while they figure out how to handle situations on their own. She suggested “that in the transition of care there is a role to play in making people aware and empowering them [with knowledge] about what [nutrition] resources are available in the community” in addition to other health services.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2007. Slide Presentation from the AHRQ 2007 Annual Conference: Medicare Hospital 30-Day Readmission Rates and Associated Costs, by Hospital Referral Regions, 2003. http://ahrq.hhs.gov/about/annualmtg07/0928slides/schoen/Schoen-17.html (accessed December 19, 2011).

AoA (Administration on Aging). 2009. Aging Integrated Database: State Program Reports (SPR) 2000–2004. http://classic.agidnet.org/SPR.asp (accessed January 12, 2012).

AoA. 2011a. Home & Community Based Long-Term Care: Nutrition Services (OAA Title IIIC). http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/aoa_programs/hcltc/nutrition_services/index.aspx (accessed November 14, 2011).

AoA. 2011b. Aging Integrated Database. http://www.agidnet.org/ (accessed November 3, 2011).

Arcand, J. A. L., S. Brazel, C. Joliffe, M. Choleva, F. Berkoff, J. P. Allard, and G. E. Newton. 2005. Education by a dietitian in patients with heart failure results in improved adherence with a sodium-restricted diet: A randomized trial. American Heart Journal 150(4):716.e1–716.e5.

Braga, J. M., A. Hunt, J. Pope, and E. Molaison. 2006. Implementation of dietitian recommendations for enteral nutrition results in improved outcomes. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 106(2):281–284.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2011. Medicare program; Solicitation for proposals for the Medicare Community-Based Care Transitions Program. Federal Register 76(73):21372–21373.

Coleman, E. A. 2011. The Care Transitions Program®. http://www.caretransitions.org (accessed December 12, 2011).

Coleman, E., J. Smith, and S. Min. 2004. Post-hospital medication discrepancies: Prevalence, types, and contributing system-level and patient-level factors. The Gerontologist 44(1):509–510.

Cook, S. L., R. Nasser, B. L. Comfort, and D. K. Larsen. 2006. Effect of nutrition counselling: On client perceptions and eating behaviour. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research 67(4):171–177.

Crouse Hospital. 2008. Crouse Hospital Care Transitions Program. http://www.caretransitions.org/documents/Crouse_2008.pdf (accessed December 12, 2011).

Feldblum, I., L. German, H. Castel, I. Harman-Boehm, and D. R. Shahar. 2011. Individualized nutritional intervention during and after hospitalization: The nutrition intervention study clinical trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59(1):10–17.

Friedmann, J. M., G. L. Jensen, H. Smiciklas-Wright, and M. A. McCamish. 1997. Predicting early nonelective hospital readmission in nutritionally compromised older adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 65(6):1714–1720.

Gaetke, L. M., M. A. Stuart, and H. Truszczynska. 2006. A single nutrition counseling session with a registered dietitian improves short-term clinical outcomes for rural Kentucky patients with chronic diseases. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 106(1):109–112.

Leas, B., and C. A. Umscheid. 2011. Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Evidence-based Practice.

Nestlé Nutrition Institute. 2011. MNA® Mini Nutritional Assessment: Overview. http://www.mna-elderly.com/default.html (accessed November 14, 2011).

Parry, C., H. M. Kramer, and E. A. Coleman. 2006. A qualitative exploration of a patientcentered coaching intervention to improve care transitions in chronically ill older adults. Home Health Care Services Quarterly 25(3–4):39–53.

Perloe, M, K. Rask, and M. L. Keberly. 2011. Standardizing the hospital discharge process for patients with heart failure to improve the transition and lower 30 day readmissions. The Remington Report, http://www.cfmc.org/integratingcare/files/Remington%20Report%20Nov%202011%20Standardizing%20the%20Hospital%20Discharge.pdf (accessed December 12, 2011).

Posner, B. M., A. M. Jette, K. W. Smith, and D. R. Miller. 1993. Nutrition and health risks in the elderly: The Nutrition Screening Initiative. American Journal of Public Health 83(7):972–978.

Raatz, S. K., J. K. Wimmer, C. A. Kwong, and S. D. Sibley. 2008. Intensive diet instruction by registered dietitians improves weight-loss success. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 108(1):110–113.

Vellas, B., Y. Guigoz, P. J. Garry, F. Nourhashemi, D. Bennahum, S. Lauque, and J. L. Albarede. 1999. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition 15(2):116–122.

Wagner, E. H. 1998. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice 1(1):2–4.

Wagner, E. H., B. T. Austin, C. Davis, M. Hindmarsh, J. Schaefer, and A. Bonomi. 2001. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Affairs 20(6):64–78.

Welty, F. K., M. M. Nasca, N. S. Lew, S. Gregoire, and Y. Ruan. 2007. Effect of onsite dietitian counseling on weight loss and lipid levels in an outpatient physician office. American Journal of Cardiology 100(1):73–75.