WELCOME, INTRODUCTION, AND PURPOSE

Gordon Jensen opened the workshop by welcoming participants and sharing background on the development of the workshop. More than a decade ago Jensen was part of an Institute of Medicine committee that examined nutrition services for Medicare beneficiaries. In that report, the committee identified impressive gaps in coverage and knowledge related to nutrition services in the community setting for older persons. Recognizing little progress in filling those gaps, in 2008 the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) proposed a workshop to address nutrition services in the community setting.

Jensen thanked the planning committee for developing the workshop agenda in a short time frame, as well as the workshop sponsors, and the FNB. Specifically, he acknowledged the sponsors:

• National Institutes of Health (NIH) Division of Nutrition Research Coordination

• NIH Office of Dietary Supplements

• Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging

• Meals On Wheels Association of America

• Meals On Wheels Research Foundation

• Abbott Nutrition

Jensen then introduced Edwin Walker, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Program Operations at the Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging, who gave the keynote address.

THE AGING LANDSCAPE IN THE COMMUNITY SETTING

Walker began by bringing greetings on behalf of the Administration on Aging (AoA) and the Assistant Secretary for Aging, Kathy Greenlee. He also thanked the audience for bringing attention to critical issues related to nutrition.

Walker described AoA as a federal agency that, in statute, is charged with advocating and “somewhat intruding” into the policy making of other federal agencies, state agencies, or any entity whose activities may impact the life of an older person. Walker said that the mission of AoA (Box 1-1) is consistent with basic American values.

Because the AoA knows that older people prefer to reside at home rather than in institutional settings such as nursing homes, its network provides supports that enable older adults to maintain their health and independence in the community for as long as possible. Walker noted that support is also included for family caregivers of older adults.

History of the Older Americans Act

Every state and every community can now move toward a coordinated program of services and opportunities for our older citizens.

—President Lyndon B. Johnson, July 1965

The Older Americans Act (OAA) was created in 1965 and signed into law 15 days before Medicare and Medicaid as one part of a three-part strategy in President Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” Medicare provided healthcare for older adults and people with disabilities, while Medicaid provided health care and supports for indigent individuals. Walker explained that the OAA was part of a plan that included Medicare and Medicaid and, although not designed as such, evolved into provision of long-term care in nursing homes. In the 1980s, Medicaid officials acknowledged that people did not want care in nursing homes by creating home- and communitybased service waivers to support the provision of care in individuals’ homes.

Medicare and Medicaid are referred to as entitlements since they are

BOX 1-1

Administration on Aging’s Mission

To help elderly individuals maintain their dignity and independence in their homes and communities through comprehensive, coordinated, and cost-effective systems of long-term care, and livable communities across the United States.

SOURCE: AoA, 2011a.

funded through mandatory appropriations, and, as a result, eligibility entitles a person to receive all benefits provided under the program. In contrast, the OAA is a discretionary program funded through annual appropriations, and individual need is assessed. It is designed to be a complement to the entitlements. OAA was planned to assist older adults in a way that would maintain their dignity and avoid their perception of the stigma associated with participating in a welfare program. It was structured to function as a partnership with state and local governments, nongovernmental entities, and, most importantly, consumers. Walker explained that the success of the program can be attributed to older adults’ real sense of ownership of the program. Often at the local level it is not viewed as a federal program, but as a local community program.

AoA programs were always planned to be two-pronged, as stated in President Johnson’s quote. One goal is to provide services that respond to individual needs and the second is to acknowledge that opportunities need to be developed for older adults in recognition of their wealth of knowledge and ability to contribute to society. AoA programs are available to anyone over the age of 60 years, but they are targeted to those in greatest social and economic need with particular attention to low-income minority older individuals, older individuals who reside in rural communities, limited English–speaking individuals, and those who are at risk of nursing home admission.

Demographics

Currently, about one in eight individuals in this country (13 percent) is an older American (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011) and, based on the current life expectancy rate, he or she can expect to live on average another 18.6 years (NCHS, 2011). Thirty percent of these older Americans live alone; since older women outnumber older men, 50 percent of older women live alone. Twenty percent of these older Americans are minorities (AoA, 2010). The numbers continue to grow rapidly. In fact, 9,000 baby boomers

turn 65 years old every day. In 4 years the population of people over the age of 60 years will increase by 15 percent, from 57 million to 65.7 million. During this period the number of people with severe disabilities who are at greatest risk for nursing home admission and for Medicaid eligibility will increase by more than 13 percent. Similar patterns are seen in demographics on the global level. It is predicted that by 2045 the population of older people in the world will be higher than that of children for the first time in history (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2010).

Characteristics of the older population include high levels of multiple chronic conditions, hospital admissions and readmissions, and emergency room usage. Walker indicated that statistics show participants in AoA programs take 10 or more prescription drugs on a daily basis. These older adults also have extensive limitations in terms of their activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, resulting in low functional levels and, therefore, requiring physical assistance.

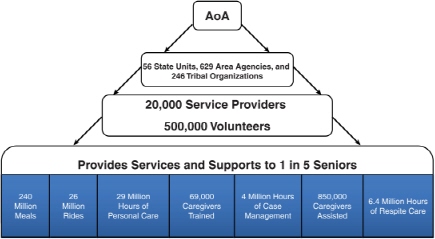

The Aging Network

The Aging Network, depicted in Figure 1-1 and created by the OAA, has evolved into this country’s infrastructure for home- and community-based services. Part of the mission is to coordinate with all of the other funding streams and organizations that touch the lives of older people. As a result of the OAA about 11 million older adults are served annually, that is, one in five older adults in this country (HHS, 2012). They are provided with lowcost nonmedical community-based services and interventions. Programs are moving toward evidence-based interventions in order to have the greatest effect on improving outcomes in an individual’s health and well-being.

The AoA is at the top of the pyramid in Figure 1-1. AoA is a very small federal agency because its strength is at the local community level. It does not provide a prescriptive set of guidelines, but it establishes basic principles describing goals to be achieved at the local level. AoA relates in a partnership manner with states and tribes, who in turn use their sovereign relationship with regional and local service areas to designate area agencies to assess what is needed in their own communities and ensure that the funds are spent in ways that are responsive to those needs.

Contracts are established with more than 20,000 local service providers, including nonprofit, faith-based, and nongovernmental entities, which Walker referred to as AoA’s “real strength.” These local service providers use the resources of more than 500,000 volunteers, often older people themselves who have a sense of ownership in the program and want to give back their time and resources to ensure the continuation of

How the AoA Helps 11 Million Seniors (and Their Caregivers) Remain at Home Through Low-Cost Community-Based Services

FIGURE 1-1 The Aging Network.

SOURCE: Walker, 2011.

services for others in need. Some of these services are listed at the bottom of the pyramid (Figure 1-1). Walker noted that consumers provide input into the design of these programs at every level—local, regional, and state.

Walker noted it takes an array of services provided by the Aging Network in the community, collaborating to achieve the mission of keeping an individual at home. These are cost-effective services and programs; the extent of contributions made at the state and local levels and by participants themselves are so significant that, for every federal dollar spent, the program generates, on average, another $3.

Many of the current programs evolved from pilot projects or demonstrations, including the nutrition program, the concept of a regional area agency on aging, and the concept of a community-based service delivery network. After demonstrating that these programs were successful models that adequately responded to individuals’ needs, they became permanent programs and features of the OAA Aging Network.

Person-Centered Approach

The OAA Aging Network has always focused on a person-centered approach to the delivery of services, creating a system and a culture that

coordinates all available resources to serve the needs of an individual. AoA collaborates with other agencies and health care systems to link services, seizing opportunities to more efficiently serve individuals.

Examples of such collaboration include working with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in the health care sector, and encouraging the local network to partner with hospitals and other health care systems to provide a more holistic approach and explore implementation of a personcentered approach. In the area of public health, AoA is partnering with the Health Resources and Services Administration to connect with community health centers and federally qualified health clinics. Other collaborative efforts include working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on prevention issues; with NIH on the translation of research into practice at the local level; with the Department of Housing and Urban Development on coordination of services for people in public housing facilities; and with the Department of Transportation (DOT) to coordinate transportation for older adults through DOT’s United We Ride initiative. On an individual basis, AoA provides assistance and information that will help older adults to age in place. This includes providing information on mortgages, pensions, public and private benefits, and protective and legal services.

Walker drew attention to the partnership developed with the Veterans Administration (VA). Rather than creating its own home- and communitybased system, the VA approached AoA and now purchases services for veterans from the Aging Network. Further information on this collaborative effort was presented by Daniel Schoeps and Lori Gerhard later in the workshop (see Chapter 4).

Nutrition Services and Food Insecurity

AoA’s nutrition program is the organization’s largest health program, providing meals and assistance in preparing meals. There are three primary nutrition programs: Congregate Nutrition Services (CN), Home-Delivered Nutrition Services (HDN), and a Nutrition Services Incentive Program. Walker reported the costs of these programs in fiscal year (FY) 2010:

• Total federal, state, and local expenditures: $1.4 billion

• Annual expenditure per person: $370 (CN), $89S (HDN)

• Expenditures per meal: $6.64 (CN), $5.34 (HDN)

Also in FY 2010, HDN provided approximately 145 million meals to more than 880,000 older adults and CN provided over 96.4 million meals to more than 1.7 million older adults in a variety of community settings (HHS, 2012). Adequate nutrition is necessary for health, functionality, and

the ability to remain at home in the community. Walker reported 90 percent of AoA clients have multiple chronic conditions, which can be ameliorated through proper nutrition. Furthermore, 35 percent of older adults receiving home-delivered meals are unable to perform three or more activities of daily living, while 69 percent are unable to perform three or more instrumental activities of daily living, putting them at risk for emergency room visits, hospital readmissions, and nursing home admissions.

Sixty-three percent of HDN clients and 58 percent of CN clients report that the one meal provided under these programs is half or more of their food intake for the day (AoA, 2011b). Researchers estimate that food-insecure older adults are so functionally impaired it is as if they are chronologically 14 years older (e.g., a 65-year-old food-insecure individual is like a 79-year-old chronologically) (Ziliak and Gundersen, 2011). Walker reported that malnourishment declines upon receiving HDN meals, as indicated by the fact that the number of HDN participants eating fewer than two meals per day decreased by 57 percent. Yet, despite receiving five meals per week, 24 percent of HDN participants and 13 percent of CN participants did not have enough money to buy food for the remaining meals in that week. Seventeen percent of HDN participants indicate that they have to choose between purchasing food and purchasing their medications, and 15 percent of the HDN participants have to choose between paying for food, rent, and utilities (AoA, 2011b). A more in-depth presentation on food insecurity in older adults was presented by James Ziliak (see Chapter 2).

Closing Remarks

Walker concluded that the work of AoA is an ongoing process. Programs continue to be developed or refined to meet the ever-increasing and changing needs of the older population. More culturally competent, culturally sensitive programs need to be incorporated, as well as more flexible programs that adapt to the needs of the people. “We need to be in the mode of ever evolving, ever changing, ever improving to meet the needs of the current and the future seniors, as well as their caregivers,” said Walker. He expressed the belief that the workshop will significantly aid the future design of AoA so it can meet those needs.

DISCUSSION

During the discussion, points raised by participants centered on reaching older adults in need. Robert Miller noted that AoA is reaching one in five older adults and asked if Walker thought that the remaining four people also need assistance. The Aging Network is responsible for and, Walker believes, is doing well at targeting those most at risk. For those that are not receiving services from AoA, there are a variety of reasons. It may be due to a lack of awareness on the part of either AoA or the older adult in need, while others may receive nonfederally funded assistance or assistance from their families. Walker noted that a comprehensive assessment is done to determine who is in most need of services. Jean Lloyd, the national nutritionist from AoA, referred to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report (GAO, 2011) that indicated the Aging Network was not reaching the majority of people experiencing food insecurity or social isolation. However, given AoA funding and the necessary prioritization of older adults in need, Lloyd said that AoA is touching those in greatest need.

THE IMPORTANCE OF NUTRITION CARE IN THE COMMUNITY SETTING: CASE STUDY

Elizabeth Landon, workshop planning committee member and Vice President of Community Services for CareLink, which represents the Area Agency on Aging for central Arkansas, presented a case study of one of their clients.

George is a 69-year-old veteran who lives alone. He was referred for Meals On Wheels through a hospital discharge meals program because he was very underweight and unable to gain weight. George was on oxygen continuously due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. His initial assessment yielded a nutrition risk score of 11 out of 19, with a score of 6 considered high nutrition risk. George was placed in the Meals On Wheels program, which included a daily telephone reassurance call to check on him and monthly nutrition education. However, as with many of CareLink’s clients, George needed more than just a meal. A dietitian helped George with a diet plan to gain weight and recommended that he use a nutrition supplement. She also referred him to other services and resources that would benefit him. George said he was unable to afford the nutrition

supplement or food and medications, so he was assigned a care coordinator with the meal program to help him.

He received $967 a month from Social Security Income—an income only $60 more a month than the poverty level. Although George had a Medicare prescription drug plan and qualified for a low-income subsidy, each of his 13 prescriptions required a copay from him which he could not afford; therefore, he did not take all of his medications. Furthermore, he had a $25,000 outstanding medical bill.

The care coordinator applied for and received Medicaid Spend-Down1 for George, which paid the $25,000 outstanding medical bill. She also obtained food stamps for him. Additionally, she applied for the Medicare Savings Program Specified Low Income Medicare Beneficiary, eliminating the copays on all 13 prescriptions and reimbursing the Medicare Part B insurance premiums that had been deducted from George’s Social Security Income check. These benefits allowed George to have $110 to spend monthly on the nutrition supplement and other necessities.

George gained 10 pounds in 6 months and improved his nutrition risk score to 5. Even though he is still at risk, he is able to live more comfortably in his own home and, because of these interventions, has not been hospitalized for 16 months. This case illustrates the key role of nutrition intervention in at-risk older people. Landon said that every day this story is repeated across America. One in 11 older people is at risk for hunger every day due to reasons such as chronic poor health, inability to shop or cook, limited income, isolation, or depression (Ziliak and Gundersen, 2011). Unfortunately, many people in similar situations are not benefiting from such services.

REFERENCES

AoA (Administration on Aging). 2010. A Profile of Older Americans: 2010. Washington, DC: HHS/AoA. http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/aging_statistics/Profile/2010/docs/2010profile.pdf (accessed December 12, 2011).

AoA. 2011a. About AoA. http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/About/index.aspx (accessed December 13, 2011).

AoA. 2011b. U.S. OAA 2009 Participant Survey Results. http://www.state.ia.us/government/dea/Documents/Nutrition/HealthyAgingUpdate/HealthyAgingUpdate6.2.pdf (accessed December 13, 2011).

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2011. Testimony Before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Primary Health and Aging, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions: Nutrition Assistance: Additional Efficiencies Could Improve Services to Older Adults. Washington, DC: GAO. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d11782t.pdf (accessed December 13, 2011).

____________________

1 The process of spending down one’s assets to qualify for Medicaid. To qualify for Medicaid Spend-Down, a large part of one’s income must be spent on medical care.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2012. Administration on Aging: Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committee, Fiscal Year 2013. Washington, DC: HHS. http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/about/Budget/DOCS/FY_2013_AoA_CJ_Feb_2012.pdf (accessed February 14, 2012).

NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics). 2011. Health, United States, 2010: With Special Feature on Death and Dying. Hyattsville, MD: CDC/NCHS. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10.pdf#022 (accessed December 12, 2011).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2010. World Population Ageing 2009. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2011. Age and Sex Composition: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf (accessed December 12, 2011).

Walker, E. L. 2011. The aging landscape in the community setting. Presented at the Institute of Medicine Workshop on Nutrition and Healthy Aging in the Community. Washington DC, October 5–6.

Ziliak, J., and C. Gundersen. 2011. Food Insecurity Among Older Adults: Policy Brief. Washington, DC: AARP. http://drivetoendhunger.org/downloads/AARP_Hunger_Brief.pdf (accessed November 15, 2011).