In considering the potential usefulness of information and communications technology (ICT) to violence prevention, speakers at the workshop explored the existing structures and processes within their respective fields and assessed any potential overlap between the two. These papers provide the beginnings of a foundation upon which this new integration can be built.

In the first paper, Cathryn Meurn presents a scan of existing ICT applications to violence prevention. Ms. Meurn explores the design and planning of interventions for various types of violence, the gaps that still exist in designing ICT-enhanced violence prevention interventions, and potential needs for monitoring and evaluation.

The second paper, by Mark L. Rosenberg and colleagues, examines the current status of violence prevention, including a discussion of the idea that violence prevention can be addressed from a public health perspective. This paper also addresses current obstacles and needs in violence prevention, and potential avenues for the inclusion of ICT.

In the third paper, Jody Ranck explores the current state of ICT and how ICT might meet the needs of public health and violence prevention now and in the future. He also discusses how ICT affects the means of data collection, program design, and community-based interventions, a situation that could pose both solutions and challenges for violence prevention practitioners.

In the final paper, William T. Riley describes current and potential evaluation methodologies for determining the success of ICT-enhanced interventions. After examining the gap between the time required to perform

traditional evaluations and the speed at which technology changes, Dr. Riley also suggests several adapted methodologies that might be better suited for rapidly changing environments.

THE ROLE OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGIES IN VIOLENCE PREVENTION

Introduction

Violence is a global problem that crosses cultural and socioeconomic boundaries. From collective to interpersonal to self-inflicted violence, its impact on health is substantial. Violence is one of the leading causes of death worldwide for people between 15 and 44 years of age (WHO, 2002). However, the actual cost and extent to which violence occurs is difficult to measure. Countless violent acts happen out of public view in offices, homes, or even public institutions.

Violence can be prevented, and this assertion has been proven true within the field of public health. Action to prevent violence has been undertaken at various levels, from the local and community level to the international system. Methods have ranged from primary prevention, aiming to prevent a violent act before it occurs, to the tertiary level, which encompasses approaches that focus on long-term care.

The goal of this background paper is to provide a brief introduction to the current and potential role that ICTs can play in the reduction and prevention of violence. This paper by no means offers an extensive study on the intersection of ICTs and violence prevention. There are many ongoing projects, and a deeper landscape analysis is recommended. Furthermore, the use of ICTs in the field of public health is in its early stages. Much of the research cited in this paper can be classified as pilot projects, and, to date, there have been no in-depth measurements of their impacts. Therefore, this paper is intended to introduce the potential of the area and to encourage collective action going forward.

The Technology and the Debate

Technologies such as the smartphone, crowdsourcing tools, remote diagnostics, and other technological innovations have proliferated over the past decade, and many of them have shifted over to mainstream use. With this technological expansion, debate has also arisen concerning the positive and negative impacts that these innovations have within communities and worldwide.

ICT can be defined as a set of technological tools and resources used to communicate, create, disseminate, store, and manage information. These can include video, radio, television, Internet programs, social media platforms, and mobile phones. Distinctions are emerging between “old” and “new” forms of media and technology—that is, between the use of television, radio, and other forms of traditional media that have been employed for decades and newer forms of media, including social media and the mobile phone.

Particularly in the case of the developing world, the adoption of the mobile phone has created a new avenue for combating longstanding problems. With more than 5 billion mobile subscriptions worldwide, phone ownership has exploded. Two-thirds of these subscriptions are in developing countries, and it is predicted that soon 90 percent of the world’s population will be within the coverage of wireless networks. Furthermore, the number of unique users active on social networks is up nearly 30 percent globally, having risen from 244.2 million in 2009 to 314.5 million in 2010 as reported by the Nielsen Company (Grove, 2010). There are more than 800 million users on Facebook; Twitter is estimated to have more than 200 million users; and more video content is uploaded to YouTube in a 60-day period than three major U.S. television networks created in 60 years (Elliott, 2010). Teens are texting at record rates, and areas such as eLearning, remote diagnostics, and mServices are growing steadily.

Despite the hype, these various technologies are simply tools that can be used either for social good or for harm. The same was true for the invention of paper, the printing press, and the telephone, all of which changed the way in which we interact with each other. These innovations all had a positive impact on society, but these tools were also conduits for such negative things as yellow journalism and mass media campaigns against ethnic groups and certain minorities. It is also important to keep in mind that technology is only a small part of any solution.

Today, these new forms of communication and new technologies have led to some fantastic outcomes, as discussed in the next section. On the other hand, they have also elicited unintended adverse consequences in the pursuit of preventing and reducing violence. Trends in cyberbullying, losses in privacy and security, and stories of perpetrators targeting victims through social media sites—all of these must be kept in mind when we speak of using these tools for social good.

Program and Intervention Designs

Collective Violence

Collective violence is perhaps the most visible type of violence and often receives a high level of public and political attention. Whether arising from violent intrastate conflicts that account for the majority of conflicts today, from the flow of displaced persons, from acts of terrorism, or from genocide, the effects of such violence can be immense. Violent conflicts have profound health effects on civilian society via increased mortality, morbidity, and disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines collective violence as

the instrumental use of violence by people who identify themselves as a member of a group—whether this group is transitory or has a more permanent identity—against another group or set of individuals, in order to achieve political, economic or social objectives. (WHO, 2002)

With the rise of new media, and advances in and increased access to technology, opportunities exist to prevent some of this violence. One of the most popular types of programs using mobile phones is based on short message service (SMS) messaging, better known as text messages. The most frequent use of SMS has been the use of one-way messaging for educational awareness, such as in Amnesty International’s SMS urgent-action appeals campaign in the Netherlands. This campaign raised the awareness of torture victims through text campaigns and in turn enabled the agency to collect “signatures” when immediate action from supporters was necessary (New Tactics in Human Rights, n.d.).

One of the most cited cases of the use of SMS, which exemplified its potential beyond simple awareness campaigns, occurred during the 2007 Kenyan election. Although initial results indicated the opposition candidate Raila Odinga was in the lead, incumbent President Mwai Kibaki was announced as the official victor. Six weeks of violence ensued during which the influential role of mobiles became apparent. Through the Ushahidi platform, those with mobile phones were able to send texts to a specific number to report on human rights abuses and incidents, which were then mapped geographically on a website. This use of both texts and online tools not only enabled the reporting of events in real time but also aided the mobilization of groups to prevent further violent outbreaks (Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, 2011). Other examples of the use of the Ushahidi platform have been during the earthquake in Haiti and, more recently, in the protests in Egypt and the crisis in Libya (Ushahidi, 2011). Nevertheless, it is important to note that this mode of communication can also make it

cheap and easy for others to spread hateful messages to incite additional violence, as happened in Kenya.

Traditional types of ICT, such as phone networks, radio, and television, can also play important roles. Radio and television have been used in many forms since their invention. One project of note that used phone networks was devised by Interaction Belfast, which created a mobile phone network to prevent outbreaks of violence between warring neighborhoods in Belfast. Volunteers in both Protestant and Catholic communities were given mobile phones to enable communication with their counterparts when potentially violent crowds gathered or when rumors of violence started to spread, with the goal of resolving the issue peacefully.

Technologies provide not only increased communication but also increased accountability and transparency. The organization Witness works to use the power of video advocacy by documenting and sharing human rights abuses via cameras. By working with constituents to use video to shed light on certain atrocities, the organization has helped to shed light on the repression of ethnic minorities in Burma and has helped to prosecute recruiters of child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.1 The organization’s training includes information on how to use video safely, which is important given the complexities to which this type of intervention can give rise.

An opportunity that deserves highlighting, particularly in the developing world, is the increasing role of the health worker. As task shifting continues to progress in these countries, community health workers can help to draw attention to indications of violence. With multiple programs now using these health workers for community outreach, data collection, and reporting via the use of ICTs and mobile phones, opportunities for leveraging technology for violence prevention exist.

Interpersonal Violence

Opportunities for leveraging technology exist with respect to interpersonal violence as well. This category includes sexual violence, intimate partner violence, elder abuse, youth violence, and child abuse.

Sexual violence Sexual violence is defined as “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion” (WHO, 2002). Research suggests that at least one in four women in the United States has experienced sexual violence (National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence, n.d.). Sexual violence is a universal problem, and it

__________________

1 For more information, see www.witness.org/about-us/witness-background.

can have deep impacts on both physical and mental health, including injury, stigma, and even death. One regularly noted aspect of this type of violence is the lack of information surrounding the magnitude of the problem. Data tend to be limited because many women do not report the violent act or seek medical services immediately afterward. Further complicating matters, data come from varying sectors, such as clinical settings, nongovernmental organizations, and the police.

SMS and geocoding can be applied to the prevention of interpersonal violence in much the same way that it has been applied to collective violence, as in the example of the aftermath of the election in Kenya. In Egypt, Medic:Mobile, a text messaging–based system, was used in combination with the Ushahidi platform in a project called Harassmap. In Egypt 83 percent of women are exposed to sexual harassment (Heatwole, 2010). The basic idea behind the program is that if a woman is sexually harassed she can send an SMS to the Harassmap number with corresponding details of the incident. This information will then be mapped on the website, allowing “hot-spots” of harassment to be identified. The project also provides help and information for victims (Heatwole, 2010). This program aims to help break through the silence that surrounds this issue.

Another program aiming to break through cultural barriers is the Mobile Cinema Foundation. This program travels to various soldiers’ camps in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and uses short films to expose soldiers to the consequences of rape. The goal is to educate the soldiers of the Congolese National Army through victim’s testimonies and discussions that are held after the viewing of the film. This form of digital storytelling can be a powerful tool both for empowering the victims and for educating offenders on the effects their actions can elicit.

Other programs are based on confidential hotlines, such as the National Sexual Assault Hotline in the United States, which victims can call for help. In a related use, in 2007 the International Organization for Migration partnered with Ukrainian mobile phone service providers to allow victims to dial a certain number to receive information and advice on migration and trafficking issues (Verclas, 2007).

Often it is an intimate partner that commits sexual violence, making sexual violence dovetail closely with intimate partner violence. Thus many interventions can help with both areas, including programs that promote gender equality, additional awareness campaigns, and microfinance programs and support networks for women.

Intimate partner violence Intimate partner violence is one of the most common forms of violence against women. This category refers to any “behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship” (WHO, 2002). Intimate

partner violence occurs throughout the world and crosses social, economic, and religious divisions. Women who are uneducated, low income, and lack support are most likely to fall victim to this behavior (WHO, 2002).

Conventional forms of technology and media have been used to prevent intimate partner violence. Examples include hotlines and awareness campaigns through both traditional and new media. Bell Bajao!, or Ring the Bell!, is an Indian program that provides a series of public service announcements urging men and boys to stand against domestic violence. The idea is that if one is hearing violence in progress, one should ring the bell and ask a simple question, such as “Can I borrow a cup of sugar?” It is likely the perpetrator recognizes that the person has heard the violence, which will interrupt the action. The organization also hosts a blog for victims to voice their experiences and access information and guidance (Bell Bajao!, n.d.).

In the United States the company Liz Claiborne initiated a Love Is Not Abuse program, which provides information and tools for men, women, and children (including teens) to learn more about the issue of domestic violence. In August 2011 it launched the Love Is Not Abuse iPhone application, which helps teach parents about teen dating abuse and demonstrates how technology, such as text messages, e-mails, and phone calls, can be conduits for committing abuse. Parents receive real-time communication that mimics the abusive and controlling behaviors teens might face in their relationships.2 This program illuminates the negative role technology can play.

On the other hand, texting can be a cheap and effective way to prevent intimate partner violence, as demonstrated by a case in Ohio in which a texting service allowed victims to report incidents silently via a simple SMS message and to make contact with a crisis intervention worker or the police without making an actual phone call. The total cost to set up the program, which used the Medic:Mobile platform, was about $380. FamilyFirst, as it was termed, processed between 6,000 to 8,000 texts per month during its first year and helped convict 18 abusers whose victims were able to report confidentially (Papillon, n.d.).

Technology can also play a role in helping to transform some of the underlying causes of intimate partner violence. Helping women gain access to both economic and societal support, such as is done through the Village Phone project by Grameen Phone Foundation, can lead to positive outcomes. The idea behind the Village Phone model is to provide a small loan and a “business in a box” to enable an aspiring entrepreneur to provide customers with access to a mobile phone and to sell mobile airtime. In March 2011, the program reports, 85 percent of the 6,876 entrepreneurs

__________________

who had been recruited into the network were women (Grameen Foundation, n.d.). This idea of women having access to a mobile device can also be found in the report Women & Mobile: A Global Opportunity, published in 2010. This report states that 9 out of every 10 women surveyed who had a mobile phone felt safer, and 85 percent felt more independent (Vital Wave Consulting, n.d.). With the rise of mobile payments and mobile money, or mFinance, and with increasing access to mobile devices, women are beginning to gain more economic independence in areas where they have traditionally been limited.

Finally, social support is important for women who have found themselves in domestic violence situations. In the developed world, such support may be derived from in-person working groups or community groups as well as from social media platforms and the Internet, which allow women to connect and share their experiences. In the developing world, however, mobile phones can play a unique role in garnering this type of support. In Senegal, the organizations Tostan and UNICEF launched the Jokko Initiative. Using SMS technology, the program allows community members to send out messages on various topics, including information on vital events, service announcements, and income-generating activities (Vital Wave Consulting, n.d.). This allows women the opportunity to promote their goods and to provide information about events they organize. Not only does this provide a chance for women to connect with each other and provide support, but also the program is also tied into Tostan’s literacy and math program.

Elder Abuse

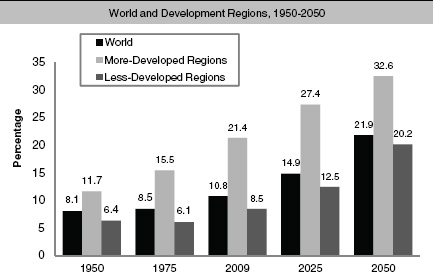

Elder abuse has received the least public attention among the various forms of violence, having historically been defined as a “private matter.” Today it is seen as an important problem that is likely to grow because of the rise in aging populations in many countries (see Figure 6-1). Elder abuse can be “either an act of commission or of omission,” and it may be either intentional or unintentional (WHO, 2002). The elderly can experience violence physically, sexually, or psychologically, and they are also susceptible to economic abuse.

Again, the use of hotlines and the sharing of information via the Internet are integral to dealing with this type of violence. The National Center on Elder Abuse has state resources such as helplines and hotlines listed directly on its website in addition to listing where to report nursing home abuses and providing information about Adult Protective Services. There are also National Elder Abuse Awareness public service announcements that call attention to the issue.

FIGURE 6-1 Percentage of population aged 60 or over.

SOURCE: United Nations, 2009.

Some sources state that a key prevention tactic could be the further use of intervention programs in hospital settings, which are currently lacking because of an absence of training in this area (WHO, 2002). Recently there has been an increase in the use of electronic checklists within the hospital setting concerning surgical procedures. Certain elements, such as signs and symptoms of abuse, could be integrated into these checklists. As tablets and electronic records become more common, a unique opportunity will appear to progress to a more holistic approach in health care. Furthermore, with the ability to train remotely, technology can be used to keep those in the health care industry abreast of the proper diagnosis of elder abuse and what to do about it.

The role of social media should also be mentioned. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, along with communications tools such as Skype, allow those traditionally cut off from the outside world to connect with both family and the wider community. According to a 2009 study by AARP, about one-third of people 75 or older live alone (Clifford, 2009). MyWay Village, a social network installed in nursing homes, allows residents to connect with new people and share their memories and experiences. Training sessions make it easy to pick up, and residents can send messages, play games, and, most important, not feel that they are isolated (Clifford, 2009).

Youth Violence

Youth violence is closely linked with other forms of violence, because youths who are exposed to other types of violence have an increased propensity toward committing violent acts themselves. Adolescents and young adults are often both victims and perpetrators of youth violence. The WHO says that violence involving youth greatly adds to the costs of welfare and health services, decreases productivity, and “undermines the fabric of society” (WHO, 2002).

Technology, particularly social media, is frequently thought to have a negative effect on youth. From online bullying to violent YouTube videos and video games, the various technologies are often cited as leading to increased violence among youth. The type of harassment that occurs through e-mail, instant messaging, and websites or via the mobile phone has even been given a name: “electronic aggression” (Hertz and David-Ferdon, 2008).

Regardless of the potential harm, youth are increasingly using social media, and there are ways in which it can be used positively. The increase in use of mobile phones by teens makes it possible to reach each one on an individual basis. A program in South Africa called loveLife launched a Web-based mobile program called MYMsta. This mobile social network allows the youth population to access information about HIV, employment opportunities, scholarships, and tips to improve their lives (Ngcobo, 2010). It also allows them to talk about concerns relating to sexual health and get responses from trained counselors.

loveLife employs other services to reach youth, such as its call-back service, which offers users free mobile connectivity to counselors. A user sends a message to the service saying, “Please call me,” and the automated system calls back and links the caller to a trained counselor.3 A similar program exists in the United States. The National Dating Abuse Helpline recently made its services available via text message by providing teens who text “loveis” to 77054 with help from trained peer advocates.4

In another effort to reach out to teens, particularly in cases of intimate partner violence or dating violence, Futures Without Violence developed the online campaign That’s Not Cool. The campaign encourages teenagers to decide for themselves what is okay and what is not okay in their relationships through the use of videos, interactive games, and an online forum for teens to share their stories and receive advice. That’s Not Cool recently launched an avatar application that lets teens create their own personalized mobile phone characters in response to animated videos addressing digital

__________________

3 See www.lovelife.org.za/what/call_me.php.

4 See www.loveisrespect.org.

dating abuse. Using text-to-speech technology, the character speaks the teen’s response, and the result is a speaking avatar video that can be posted and shared with peers on Facebook and Twitter.5

To deal with youth gangs, an innovative partnership involving the Chicago-based organization CeaseFire had been developed that combines science and street outreach to track where violence is heating up and to interrupt in order to calm the situation down. With Ushahidi, Medic:Mobile, and PopTech, the project PeaceTXT will look at how mobile tools, such as those used by other crisis-mapping organizations, and mobile messaging can accelerate CeaseFire’s existing success in decreasing deaths (Meier, 2010).

Child Abuse

Child abuse includes infanticide, mutilation, abandonment, and other forms of physical and sexual violence (WHO, 2002). It is a universal problem and often increases the likelihood of adverse health outcomes in adulthood. There is also a cultural aspect to child abuse because the standards and expectations of proper parenting can vary in different countries and societies. More often than not, the term “technology” combined with the idea of child abuse conjures up images of child pornography on the Internet and other negative ways in which recent innovations have harmed children. But technology also offers unique ways to prevent this type of abuse.

One underlying risk factor for a parent committing child abuse is a lack of education concerning a child’s development (WHO, 2002). There has been a recent rise in health text messaging programs geared toward reaching traditionally underserved groups with important health information. For instance, in the United States the Text4Baby program piloted by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is a public–private partnership that provides pregnant women and new mothers with free health text messages. The messages range from tips on how to care for a baby to information on what to expect during pregnancy. Evaluations of the program are scheduled to be made available in 2013, and the model is already being taken abroad with interactive voice response technology, which relies on voice instead of text. Another text program that HHS is expected to roll out next year is Text4KidsHealth. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) will develop text messages on nutrition and physical activity to be used for future programs targeting the parents of children from 1 to 5 years of age (HHS, n.d.).

The mobile phone can act as a reporting tool for cases of child abuse. As seen with regard to collective violence, there is power is capturing

__________________

5 See www.loveisrespect.org.

images of typically ignored issues and bringing them to light in the mainstream media. Using one’s mobile phone in combination with community reporting is an easy way for stories to hit the Web that will be shared across masses of people through YouTube, blogs, and other social media channels (Nyirubugara, 2010). One can do a simple Google search online and find numerous online campaigns, blogs, and other videos calling for action and for attention to the issue of child abuse.

The traditional hotlines available to children, such as the National Child Abuse Hotline that is run via Childhelp, offer another approach to assistance and prevention. Childhelp also has information on its website to help children determine if they are being abused and what actions to take.6 Also, because health professionals play a key role in identifying any signs of child abuse in their patients, incorporating such identification as part of their training—or including information and prompts in the tools they use, such as checklists or reminders—could help prevent additional cases of abuse.

Self-Directed Violence

Violent acts that a person inflicts upon himself or herself are classified as self-directed violence. This includes both suicidal behavior and self-abuse. In the United States more than 35,000 people commit suicide every year, not including suicide attempts or self-abuse. Annually more than 1 million people attempt to take their own lives, and approximately 60 million Americans experience a mental health disorder, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, which can be risk factors for self-directed violence (National Alliance on Mental Health, 2010).

The WHO says that proper diagnosis of mental disorders is important, as is support for those who are contemplating destructive acts. Again, Telehelp lines and call centers are influential. Numerous lifelines, hopelines, and other crisis services are available. Opportunities now also exist for easy access to information and therapies online. The rise of online support groups also allows for those who are suffering to reach out and connect with others, which helps them understand that they are not alone. Awareness and access to services permits many to move past the social stigma often attached to depression and suicide.

There has been some debate over the creation and use of suicide prevention applications on mobile platforms. To have the applications verified and appropriate for the user, in addition to the possibility of producing any impact, is challenging. The QPR Institute released an Android app that turned the book The Tender Leaves of Hope: Helping Someone Survive

__________________

6 See www.childhelp.org.

a Suicide Crisis into a digital booklet in hopes of reaching more families and individuals.7 Some mobile applications let users track their moods and experiences, providing supplemental information for them as well as for their therapists. An app called “mobile therapy” has a “mood map” that pops up on a user’s screen that allows the user to indicate how he or she is feeling. The app responds by offering “therapeutic exercises” ranging from “breathing visualizations to progressive muscle relaxation” as well as ways to disengage from a stressful situation (Trudeau, 2010).

Again, there are risks involved. Technology and media are often blamed for suicide, particularly teen suicides related to cyberbullying. It is difficult to determine how great a role media and technology play in these deaths. Some instances become sensationalized, such as the 2008 case of a Florida teenager who posted online a live-stream video that showed his suicide, as he was encouraged by others he was chatting with online at the time (Friedman, 2008). With more than 87 percent of teens (ages 12 to 17) using the Internet and 19 million teens sharing their lives through text messages, this is definitely a cause for concern. As much as mobile phones, chat rooms, and other forms of communication can help teens work through their issues, they can also push teens in the opposite direction.

Overarching Gaps and Trends

From the program implementation cases above, several overarching gaps and trends begin to emerge, many similar to other fields using similar tools. In this section we will examine some of these gaps and what can be done about them.

Data Collection and Surveillance

A common problem in the field is the collection, analysis, and distribution of valid and useful data. As stated in the first WHO World Report on Violence and Health, countries around the world are at different stages of capacity for collecting data (WHO, 2002). There is a lack of quality and uniformity in the data. In addition, the problem of only knowing “the tip of the iceberg” remains, as research indicates many instances of violent acts remain unreported.

The use of ICTs can create certain efficiencies in data collection as well as improving its quality and associated information flows (Ranck, 2011a). Currently, in part because of the need for donor reporting, data collection is fragmented and siloed. Opportunities to increase the collection of and access to data and health information have increased, in large part because

__________________

7 See https://market.android.com/details?id=qprinstitute.crisis.

of the use of mobile phones in the developing world. Electronic capture of data can decrease human error and increase the speed of analysis.

Increasingly, people in the field of ICTs and their uses have been talking about the use of unique identifiers, such as biometric data, and the use of electronic health records to track patients has become increasingly commonplace. This type of data capture and storage can create better co-ordination across health systems and allow them to share data horizontally (Ranck, 2011a). Having access to broader data could lead to different actions and outcomes. Furthermore, the use of ICTs and mobile devices could aid health professionals, from doctors to community healthcare workers, in accessing and retrieving information.

EpiSurveyor and Commcare are examples of tools that have just started to be used in this area. EpiSurveyor allows anyone to create an account, design forms, and download the forms to a mobile phone in order to collect data for free. Commcare is free and open-source software that provides community healthcare workers with aid in case management through their mobile phones. The software contains registration forms, checklists, danger sign monitoring, and educational prompts and is designed to help manage the enrollment, support, and tracking of all of a community health worker’s clients and activities. The data that are collected are sent to the cloud for easy analysis and retrieval.

Another project, ChildCount+, is a platform designed and used by the Millennium Villages Project. ChildCount+ uses SMS to assist and coordinate the activities of community-based healthcare providers such as community health workers. These workers can use text messages to register patients and report on their health status. This information is sent to a central Web-based dashboard that can then provide a real-time view of the current status of the community.8 There are also numerous other software kits being used in the developing world, such as EpiInfo, OpenXdata, Open Data Kit, Open Dream, Open MRS, OpeneLIS, Open-Clinica, District Health Information System, Managing News, Sahana, Geo-Chat, Riff/Evolve, Mesh4x, Ushahidi, and Epidefender.

Research and Evaluation

Along with the needs listed above for data collection and surveillance, there is also a lack of common metrics for monitoring and evaluation, especially for programs using ICTs and mobile devices. There are serious insufficiencies in rigorous evaluation of the many pilot programs that are using these new mediums of communication and determining their overall impact.

__________________

8 See www.childcount.org.

A unique advantage of ICTs is that they offer the possibility of real-time evaluation. Furthermore, linking data from one program to others could lead to a clearer view of where the field is and where it is heading. This could have important effects. However, issues remain, including a lack of understanding of the capabilities around the use of ICTs, a lack of common data standards that support interoperability, and the need to develop information-sharing policies (Ranck, 2011a). Conversations concerning the “enterprise architecture”—the “plumbing” of systems—are in the early stages. We have yet to hit a point where projects are no longer functioning in siloes and where sharing data leads to a leveraging of each other’s results. “Interoperability,” or the ability to share data quickly and accurately across different application and through the health system, will be an important property to develop in the coming years if the full potential of ICTs and mobile devices is to be realized.

A final issue related to sharing data across silos is the problem of privacy and security. Concern about the ability of users to retain anonymity, especially given the nature of collective violence or intimate partner violence, is understandable, and such concerns should remain at the forefront of any project implementation. Data ownership is another issue that raises various concerns, particularly as projects strive for scale in implementation or begin to share data between programs or with the health system at large.

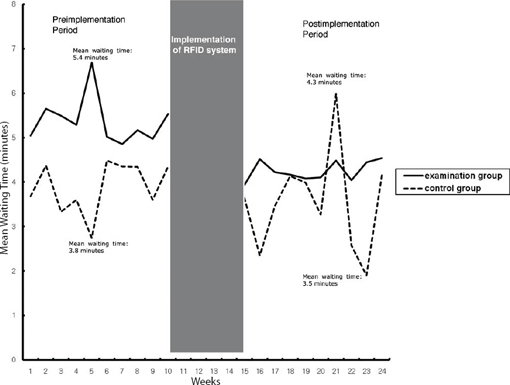

Dissemination and Implementation

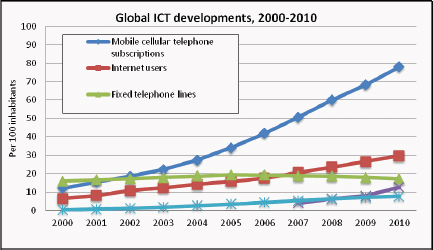

ICTs can play a pivotal role in the implementation of violence prevention programs throughout the program and intervention design section. Multiple modes of telecommunications exist, but the mobile explosion both within and outside the United States provides additional opportunities for impact (see Figure 6-2). Common elements of program implementation can include the use of electronic forms and checklists, remote training for healthcare professionals, the use of crowdsourcing and social media platforms, and the use of SMS and video or television.

A larger issue remains, however, which is the exchange of information and lessons learned throughout not only the violence prevention community but also the public health field at large. Online platforms can aid in the dissemination and sharing of knowledge. Although not yet widely instituted, GHD Online and the mHealth Alliance’s Healthunbound platforms offer a peek into what is possible. With the rise of webinars and remote access to meetings, and with the ability to share presentations online through websites such as slideshare, avenues for information sharing and collaboration have increased.

Finally, institutions should not overlook these platforms for supporting their advocacy campaigns and their ability to raise funds for the

FIGURE 6-2 Global ICT developments, 2000–2010.

SOURCE: ITU, 2011.

implementation of programs. Multiple programs now use e-cards and online petitions or request advocates to share program information with their social networks. Text campaigns have become particularly popular over the past few years, allowing individuals to donate to certain causes via their mobile phones. Eight days after the earthquake in Haiti in 2011, the American Red Cross had raised approximately $22 million via text messaging (Heath, 2010). Donors texted the word “Haiti” to 90999, and a $10 pledge was automatically added to the person’s phone bill.

Recommendations

1. Undertake a full-landscape analysis of the use of ICTs in violence prevention.

Time and resources should be dedicated to a full-landscape analysis on the intersection between ICTs and the field of violence prevention, with particular emphasis on the mobile phone in relation to the developing world.

2. Learn from other fields and each other.

The mServices and mHealth spaces in particular have a lot to offer in terms of uses of new innovations and lessons learned. Conversations about the employment of electronic health records, interoperability, and the development of common metrics to evaluation are being explored. Furthermore, the types of violence outlined in this paper are interrelated

and interdependent in various ways. Using new platforms for information sharing and collaboration as well as sharing data and lessons learned could greatly push the field forward.

3. Develop common metrics for monitoring and evaluation.

With the ever-pressing need to know if these technologies are making a positive impact, the development of common metrics for monitoring and evaluation is important. With the ability for near real-time analysis of data, and given the infancy of this field, collaboration on metrics and the evaluation of programs will be vital for knowing what works and what does not.

4. Further explore privacy issues.

Given the sensitivities that surround certain types of violence, such as intimate partner violence, the need for anonymity is of utmost importance. Issues concerning user privacy, the sharing of data, reporting, and so forth need to be further explored. The technologies themselves must be investigated to make certain that they are not allowing sensitive information to be leaked to a wider public, for example via GIS mapping or forums on the Internet.

5. Address development factors—move beyond intervention.

Emphasis must be given to many of the underlying development factors that can lead to the instigation and continued perpetration of violence. Factors such as poverty, lack of access to the health care system, lack of access to education, and economic inequality can make any person or society ripe for violence. ICTs can be pivotal in addressing these issues, as with the use of mFinance to address poverty or with community health workers using computers or mobile phones to help expand access to health care and education.

THE STATE OF GLOBAL VIOLENCE PREVENTION:

PROGRESS AND CHALLENGES

Mark L. Rosenberg, M.D., M.P.P.

The Task Force for Global Health

Frances Henry, M.B.A.

Advisor, F. Felix Foundation

Alexander Butchart, Ph.D., M.A.

Department of Violence and Injury Prevention,

World Health Organization9

The field of global violence prevention has made some tremendous advances in the past 35 years. In some very important ways, however, it remains “stuck,” facing a number of serious obstacles, some that are generic for global health and others that are unique to the field of violence prevention. This paper sets the stage by describing some of these advances and then presenting the obstacles in order to explore whether ICT—including the new social media—can inspire ways to surmount these obstacles.

Perhaps the most important advance the field has made is to have helped people understand that violence is not inevitable, that it is not just an unavoidable aspect of daily life, and that it is not just one aspect of the existence of evil in this world. The importance of this advance can be seen in the story of smallpox, a disease that for centuries killed tens of millions of people every year. For many people, smallpox was seen as a recurring and unavoidable plague—until it became the first and the only human disease that has ever been eradicated (Foege, 2010). In 1806 President Thomas Jefferson wrote to congratulate Edward Jenner on his discovery that inoculating an individual with cowpox vaccine could confer immunity to smallpox. Jefferson told Jenner that within a few years his discovery would make smallpox a disease known only to history. It took a few more years than Jefferson thought. In 1973 Dr. Bill Foege was sent to India, where there were 87,000 cases of smallpox and the situation appeared quite hopeless. Foege shifted the strategy from mass immunization to the containment of outbreaks by vaccinating only those within or exposed to infected villages. This led to the eradication of smallpox in India and then the rest

__________________

9 One of the authors is a staff member of the World Health Organization. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication, and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the World Health Organization.

of the world. Smallpox eradication was the holy grail of global health, and this was an extraordinary achievement.

Sometimes tremendous leaps are made with a disruptive innovation; smallpox eradication was achieved when the containment strategy replaced mass immunization. The Swedish strategy for eliminating road traffic deaths was inspired by the eradication of smallpox. In Vision Zero, Claus Tingval put forward the idea that road traffic injuries are not “accidents”—not unpredictable and unpreventable acts of fate—but rather are very predictable and preventable events, and he suggested that we do not have to accept any number over zero. He was at first ridiculed for this idea, but now Sweden is well on its way to achieving this goal, and the European Union has adopted the Vision Zero goal for 2050. The idea that violence can be prevented is a similar sort of paradigm shift that can change the future.

The substantial changes that this paradigm shift brought about can be seen in the area of child sexual abuse. This was a problem to which the response used to be denial until it happened, and then perpetrators were sent to jail and victims to therapy. However, Fran Henry, through Stop It Now, helped to change the paradigm and demonstrated that identifying people at risk for perpetration and providing them help could actually prevent abuse from occurring. She made the case for prevention, and it has now become commonplace for the public to expect that preventive steps be taken. The failure to prevent child sexual abuse associated with the Catholic Church has provoked huge protests, and the most recent scandal involving a football coach at Penn State resulted in high-level firings. These are the results of a change in the paradigm—of a new and widespread belief that child sexual abuse can and must be prevented. Many believe that media attention to the Penn State case contributed to the response. This raises the possibility that change happens more quickly when the whole world is watching and suggests that ICT can help to spread the notion that violence is preventable and can accelerate positive change.

Significant Progress

Significant progress has been made in making it clear that violence is not “evil in the world” through the clarification of a definition of violence developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the WHO. The agencies have defined violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation” (WHO, 2002). The agencies have also helped to identify specific categories of violence: child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, youth violence, collective violence, sexual violence, elder abuse,

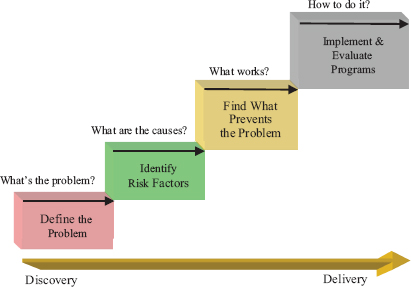

FIGURE 6-3 CDC Public Health Model.

SOURCE: CDC, 2008.

suicide, and self-directed violence. And they have helped to make substantial progress in each of these areas by asking and answering four questions: What is the problem? What are the causes? What works to prevent it? How do you do it? (Figure 6-3). We can see substantial progress has been made in answering each of these questions.

Progress Has Been Made in Achieving a Better Understanding of the Problem

We have developed a substantial science base ranging from knowledge generation (research) and knowledge integration to knowledge dissemination and knowledge application (delivery). We have demonstrated that the burden of violence is large and truly global; there are an estimated 1.5 million deaths each year, with more than 90 percent of the burden born by low- and middle-income countries. We also now understand that the burden of violence is exacerbated by its impact on other health and social problems. Exposure to violence increases the risk of mental health issues (e.g., depressions and anxiety) and physical health problems (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, and cancer) across the lifespan (Repetti et al., 2002). Exposure can also compromise cognitive development as well as the social development of communities and nations (WHO, 2008). Most important,

we have generated important knowledge about what works to prevent violence (Rosenberg et al., 2006; Mercy et al., 2008; WHO, 2010), although we have much to learn about how this can be applied in low- and middle-income countries.

We Also Have Made Progress in Understanding the Causes and Connections Among Different Types of Violence

There are identifiable risk factors and protective factors for each type of violence, many of which affect more than one type of violence, e.g., alcohol-related, child maltreatment, and exposure to violence (Rosenberg et al., 2006). We have learned that different types of violence are connected in many ways. A cycle of violence can begin, for example, with child neglect at birth, leading to hypervigilant children who are less likely to be calmed and more likely to participate in youth violence, and then intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and suicide when they get older.

We have a much better understanding of how to implement violence prevention programs and interventions. We have learned the value of collaboration among different sectors and disciplines, and we have seen the value that is added when police and public health, instead of fighting for control, work to collaborate effectively (Rosenberg et al., 2010). We have seen the important role that advocacy groups, often led by survivors, can play in program design and delivery. Advocacy groups have made substantial progress in many areas of violence prevention as they have expanded from treatment only to treatment and prevention, with prevention and treatment components working together rather than competing for funds. The place of public health in violence prevention has been well established, with the CDC and WHO providing leadership. The WHO has adapted the CDC model for use around the world. The organizations’ success is reflected in a substantial worldwide demand for technical assistance for violence prevention, with 44 countries around the world receiving WHO technical support as of September 2011 (A. Butchart, personal communication, 2011). The institutions that work in the field of violence prevention have also been strengthened: The WHO established a growing network of officially appointed Ministry of Health focal points for violence prevention, with a global total of more than 130 focal points in 2011.

The Challenges Before Us

But in some important ways we are still stuck. In fact, we are still stuck getting answers to the “four questions”:

1. What is the problem? There is much more work to do in overcoming the sense of fatalism that pervades so much of our thinking about violence, in countering the notion that violence is an inevitable part of human life and thus not preventable. We also need to overcome the separation of different types of violence into silos, so that researchers and practitioners in different fields of violence prevention can benefit from understanding the common roots and interconnections among different types of violence across the lifespan. We need more resources for a better understanding of the social and economic determinants of violence. One consequence of these root causes is that violence affects the most needy, poor, and vulnerable disproportionately but they do not set the spending priorities. There is still a need for more interdisciplinary collaboration. Many people still do not believe that violence is really a public health problem, but instead feel that it “belongs” to criminal justice. We need to overcome the “privacy ruse”—the belief that interpersonal or self-directed violence is a family affair and that what happens in the family (or nation) stays in the family (or nation). Stigma and shame keep people and countries from reporting many kinds of victimization, such as rape. Nations do not want to stigmatize themselves by saying they hurt their children, their women, their elderly, or themselves.

We are also hindered in our understanding of violence prevention because we use the wrong calculus to identify costs and benefits. Traditionally the biggest threats to our own health have been traditional infectious diseases, such as smallpox, polio, MDRTB, HIV/AIDS, and cholera. Most people do not realize that the well-known philosopher Martin Buber was really the first philosopher of surveillance. His work tells us that there are two types of surveillance. The first is “I and IT surveillance,” which follow the principle, “My country is at the center of the universe, and I relate to others only insofar as they contribute to my own little agendas or pose threats to my own health.” The second type of surveillance is “I and THOU” surveillance: “We flourish best when we treat others with respect, care, and equality. We add value to this global human endeavor by understanding the needs and contributing to the lives of others. We are compassionate” (Buber, 1923). The International Health Regulations look at I and IT surveillance, taking account only of those conditions that pose a direct threat to the security of other countries. But if we let this guide our efforts, then we fail to account for the costs to the people who suffer in the developing world from interpersonal and self-directed violence because this is not seen as contagious and importable into our own countries. Using “I and It” surveillance will mislead our efforts in formulating policy and setting our priorities if we fail to see that interpersonal violence is intimately connected to group violence and in the end it will pose a threat to our own security.

ICT may help facilitate “I and THOU” surveillance by contributing to the breakdown of the walls and borders that separate us as residents of

countries. They open whole new possibilities for conducting surveillance and open up the participation of many new groups and types of people to the process of surveillance, to analysis, and to the application of surveillance data.

2. What are the causes? Positive relationships are crucial for violence prevention. There is much more work to be done in understanding how to improve relationships and break the cycle of violence. Additionally, there is a particular risk that faces all of us: becoming disconnected while believing that we are becoming more connected. There is a risk that increased reliance on indirect communication methods such as cell phones and e-mail may diminish direct personal communications and thereby make it more likely that violence will be employed against someone whose face and persona are not known. Thus, we must also be cognizant of the limitations of these new technologies and realize that they may also be used to cause or facilitate violence.

3. What works to prevent it? Although much progress has been made in understanding what works to prevent violence, we lack sufficient proof of effectiveness for many interventions in low- and middle-income countries, and, without the proof of effectiveness, donors do not want to invest in preventive interventions. Ideally we should be able to provide a short list of specific interventions or “best buys” that have been proven to be effective and are ready for application in developing countries. However, few interventions have been implemented in developing countries with the capacity to evaluate the outcomes and collect the data needed to measure cost-effectiveness. This is a vicious cycle because without the necessary investment, we cannot develop the evaluation capacity needed to demonstrate effectiveness. The strongest case possible must therefore be made for investing in building the capacity to take interventions that have proven effective in developed countries and systematically implement and evaluate them in developing countries (WHO, 2008). What role can new information and communications technologies play in preventing violence in low- and middle-income countries? These technologies may enable us to accelerate progress in finding viable and effective strategies in low-resource environments.

4. How do you do it? One fundamental obstacle to progress is the absence of commitment by decision makers to enact solutions and try ideas. This field is markedly under-resourced. The consequences of this include an intense rivalry among organizations that compete for the same limited pool of dollars and a lack of resources to build the violence prevention foundations that, at a country level, are required to ensure that prevention activities are sustained over time. We need to overcome skepticism about the feasibility of delivering complex social interventions in resource-poor settings, and we struggle with the large time lag between prevention program delivery and reduced rates of violence for interventions such as parent

training and life skills training. Those working in global violence prevention also have to deal with the significant cost of preventive interventions. In the current economic climate, with increasing cut-backs in foreign aid, people want to stick with what we have already started (i.e., programs dealing with AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and infectious diseases) and not get into something that is new and therefore a lower priority. We also do not know how to reach out to high-risk groups. In addition, we have a lot to learn about scalability—we can do demonstration projects, but we have had little experience with scaling up programs that work. We also need to do a better job at integrating the different phases of the public health model. Ideally, surveillance, evaluation, and response would be closely linked. Instead, we collect the data, analyze it, and then 3 years later perhaps it is applied or used. We have not developed the capacity to implement solutions to overcome the many bottlenecks that occur here. This is a universal problem for global health and one where ICT may be of great help.

INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGIES

AND THE FUTURE OF GLOBAL HEALTH

Jody Ranck, Dr.P.H.

Public Health Institute

Introduction

The past decade has witnessed a remarkable and truly global technology revolution unlike virtually any other. The mobile phone has placed more computing power in the hands of more people than even telecommunications experts in the 1980s thought would be possible. An executive from AT&T predicted that the global market for cell phones would peak at approximately 100,000. But by the end of 2011, according to the International Telecommunications Union, almost 6 billion people had access to mobile phones (ITU, 2011). The average smartphone today contains more computing power than all of NASA’s computing resources at the time the first man was sent to the moon. Social media is an important driver of this growth.

In contrast to most public health practitioners’ perspectives, Africa is one of the fastest-growing markets for Facebook. In fact, Facebook is becoming an important driver of Internet growth in Africa, because it has now become the leading site visited by Internet users on the African continent (Jidenma, 2011). Although Africa has become the continent with the fastest growth in Facebook use, there are important disparities in access and growth rates. Nevertheless, the developing world has rapidly become a major focus of the marketing departments of most major social media

platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook, and Google. The role that these platforms played in the Arab Spring of 2011 can certainly be overstated, but there is little denying that access to social media platforms that are essentially many-to-many self-publishing platforms, mostly accessible by mobile phones, is having a major impact on the way ideas are communicated, new knowledge is generated, and, as we will soon see, new research on the understanding of human behavior is being conducted.

Global health experts can no longer afford to view social media as trivial playthings of adolescents. These are major platforms with which to engage the public and to innovate in areas such as civic engagement, public policy, and technology development, and they are transforming the way we think about education, technology development, the media, politics, social movements, and science. These are all critical dimensions of public health, more largely, and for developing the next generation of global violence prevention tools and policies.

In this paper I will outline some of the most important technological innovations involving the mobile and social media platforms and provide some preliminary examples of the key lessons and impacts that these tools have had. There have been many early research studies on mHealth and social media tools, but these often suffer from small sample sizes and various other methodological shortcomings, so there are relatively few robust evaluations of the technologies (Mechael et al., 2010). In the discussion that follows, I will focus on innovations in mHealth and social media and how these have created the enabling conditions for open data, crowdsourcing, citizen science, new visual cultures and advocacy, the gamification of health, and open innovation, all of which can lead to a new approach called “open health.” I will conclude with some observations on how these may lead to new strategies for global violence prevention efforts.

Social Media: Amplifying the Self and New Forms of Cooperation

Since the early 2000s, social media tools have grown dramatically in use and scope, becoming mainstream communications tools that have helped foster what some have termed “new economies and cultures of sharing.” From Flickr to Facebook, the demographics of the adoption of these tools have grown in unexpected ways, and they have become important, if not central tools, for companies, nongovernmental organizations, and governments to share information and communicate. Early on, platforms such as Flickr proved to be virtual spaces where acts of resistance to gender norms could be acted out by youth; for example, in the Arabian Gulf states, where public spaces are strictly segregated by gender, teenagers used Flickr as a space for interacting across gender lines. Such examples illustrate how the use of many-to-many communications platforms can take on distinctly

political tones. The Arab Spring was just one of many instances in recent history in which mobile devices and social media were used to amplify voices of dissent and tell compelling oppositional narratives in public life. The Orange Revolution in the Ukraine and the toppling of Philippine president Joseph Estrada are further examples of the use of SMS or text messaging to coordinate resistance movements or what Howard Rheingold has termed “smart mobs” (Rheingold, 2003).

In January 2008 one of the most powerful examples of the use of social media and mobile devices and of the new forms of cooperation that they entail occurred. During the Kenyan electoral violence, bloggers critical of the national government’s media blackout created an open-source platform for crowdsourcing information about both violence and counter-violence via SMS messages that could be mapped on the platform called Ushahidi (Swahili for “Testimony” or “Witness”). Blogger Ory Okolloh suggested the need for a platform for information gathering, and a network of bloggers created the site in approximately 1 week. Incidents could be reported via mobile devices using a short code and were then verified by local groups on the ground and mapped in order to provide a visualization of the violence. Today this platform is used globally from Russia to Washington, DC, by groups involved in a variety of humanitarian and human rights issues. In its wake, a number of similar tools have been developed to raise awareness of gender harassment in Egypt (HarassMap) and violence against girls; in one example, a reporting tool similar to Ushahidi was even merged with open data initiatives in order to map murder rates (Evans, 2011). Social media have been a major driver in the move toward greater transparency and in the growing area of open data initiatives that have taken place in a number of formerly closed institutions, such as the World Bank.

Such examples point to the sorts of roles that the phenomenon of crowdsourcing that has arisen from the social media landscape can play in global health. Several years ago the pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly launched an open innovation platform called InnoCentive to tackle difficult-to-solve scientific problems. The firm, after spending millions of dollars and many person-years without solving specific problems, began to reach beyond its own walls and disciplines to find assistance in solving these challenges. It placed problems on the site, which allowed potential solution finders to register and submit approaches to solving the problems. Frequently the company discovered to its surprise that the problems were easily solved by scientists halfway around the world who approached the problem through a different paradigm or discipline that made the challenge quite easy to solve. The success of InnoCentive has unleashed a wave of platforms and strategies to drive innovation and solve difficult scientific and health challenges by recognizing that our traditional forms of knowledge creation have not necessarily kept up with the technologies and new forms of sociality

that they engender. A new science of asking questions has arisen, and platforms are now being used to “micro-task” problems and work into smaller pieces that can be easily solved, often providing income to micro-taskers using platforms such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk or the developing world platform, Jana. An example of such work that has taken place in developing countries is the group of Trinidadian and Brazilian students who developed a micro-tasking tool for performing medical diagnostics of digitized X-rays on mobile phones that users would scan for eye conditions; this was the winner of InfoDev’s microwork challenge, “m2work” (InfoDev, 2012).

Cooperation and the Commons

Elinor Ostrom won the 2009 Nobel Prize in economics for her path-breaking work on the commons and the strategies and tools used to manage the commons in the area of natural resources. Her work is all the more salient in our new world of ICT, because the examples demonstrate the power of the tools of cooperation. The commons can become an invaluable companion to these tools through creating a basis for shared resources. From open-source software to innovation commons such as the Science Commons or public goods such as health, we see a growing movement to deploy commons-based assets alongside the tools of cooperation in order to drive innovation and problem solving. As much of the world enters a period of prolonged financial crises, global health experts will need to become more literate and skilled in strategies for commons-based approaches that rest on an economics of sharing that can be disruptive to traditional approaches. In the biological sciences we have examples such as the ProteomeCommons, which involves protocols for sharing terabytes of data over the Web (Weinberger, 2012).

mHealth and Public Health 2.0

The near-ubiquity of cell phones in most low- and middle-income countries has created an unprecedented opportunity to extend the reach of community health workers as well as to provide a channel for public health messages and two-way communications. Mobile devices are increasingly playing an important role in data collection with open-source tools such as DataDyne’s Epi-Surveyor or INSTEDD’s Geochat, which enable the creation of forms and the transmission of data. The Praekelt Foundation and organizations such as Cell Life in South Africa have pioneered the use of SMS for HIV prevention, testing, and drug-adherence regimens. Beyond texting, there are new tools for eye exams, infectious diseases, vital signs measurement, and microscopy that are in various stages of development and that will be able to take advantage of the augmented computing power

of smartphones. Smartphones are coming down in price as well, as exemplified by the $80 offering that HTC has developed for the Kenyan market. In countries such as Kenya and the Philippines, where the mobile industry has made extensive inroads, there are new possibilities for mHealth to piggy back on the mobile industry to enable micro-insurance schemes, such as the one by Changamka aimed at enabling pregnant women to cover antenatal care, child delivery, and postnatal care. These systems can also be extended to vouchers for supplementary feeding, cash incentives, and the payment of health workers (Gencer and Ranck, 2011).

Beyond mobile devices, the broader social media system is increasingly playing a public health role in the areas of epidemiology, participatory planning, and biosurveillance. Public Health 2.0 offers a new paradigm that democratizes the way science is practiced. In February 2011 a mysterious fever appeared among participants at the DomainFest Global Conference (Garrity, 2011). One of the attendees used Facebook to reach out to other participants to inquire about their symptoms. Within a few days, before the Los Angeles County health department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had even launched an investigation, the participants had diagnosed the outbreak themselves as legionellosis and had entered the diagnosis on Wikipedia. HealthMap and Google’s Flu Tracker, along with Twitter, are some of the more robust mapping/crowdsourcing tools that are becoming increasingly prevalent in public health science and practice. Rumi Chanara of Harvard used Twitter to track the 2010 cholera outbreak in Haiti (Chunara et al., 2012). These platforms are in essence large repositories of data which new data-mining tools can use that to make sense of much faster than is possible with traditional methods.

Big Data and Data Mining

Given the proliferation of mobile devices and data-collection devices, particularly with the emerging Internet of things including the billions of devices that can collect data and send them to the Internet, the major challenge has been to make sense of all of this data (Ranck, 2011b). The combination of cloud computing and big-data analytical tools such as Hadoop has enabled data scientists to take vast volumes of data, too big to fit on the typical server, and parse these data very rapidly. Tools such as IBM’s Watson can now scan several hundred million pages of medical text in seconds or fractions of a second. These tools are capable of sorting through hundreds of millions of tweets and making sense out of this chaos, often at a much lower price than conventional approaches. Such tools have already been used to analyze data about violence, such as shootings in Camden, New Jersey. Jeffry Brenner used big-data analytics to sort through 8 years of medical billing records and to discover that 80 percent

of costs were associated with 13 percent of patients, and that much of the care was neither medically effective nor cost-effective. This discovery created the foundation for a new partnership to address violence prevention efforts. Another research effort, this one carried out by Harvard University researchers, uncovered indicators of risks of domestic violence in patients’ electronic medical records that may help clinicians identify early risk factors that can prompt earlier interventions (Joelving, 2009).

Gamification

A final area where social media and ICTs can play a role in the future of global health is gaming. Gamification refers to the deployment of gaming tools, incentives, and technologies within the worlds of business, research, creativity, and innovation. In 2011 a major breakthrough in the area of HIV research came to light through the success of the online research and gaming platform Fold.it (Marshall and Nature, 2012). Researchers from the University of Washington created an online game that allowed users to manipulate three-dimensional structures of proteins on their home computers, which were then scored for the best (lowest-energy) configurations of the enzyme critical to some HIV drug therapies. For several years bench scientists had failed to come up with better configurations and thus had sought to crowdsource alternatives. Within several weeks amateur gamers had solved a problem that had plagued these scientists for years. There is growing use of games such as this designed for mobile devices to use the incentives and critical thinking fostered by game dynamics in order to encourage public participation in citizen science or behavioral change (Fogg, 2002; Bogost, 2010).

ICTs and Global Violence Prevention: Lessons

for the Future of Global Health

In this paper I have outlined some of the key technology trends that are likely to play a significant role in general public health efforts in the future. Although many of the examples are from developed countries, we are seeing a dramatic growth of these tools for global health efforts. Some of the tools have been developed with violence prevention efforts in mind, but the violence prevention arena lags significantly and could explore these tools in more detail. For example, the United Nations Global Pulse platform is a big-data project that seeks to stimulate data philanthropy, sharing, and analytics in order to predict political crises much earlier through finely tuned analyses of the “data exhaust” from media, NGOs, evaluations, and so forth. A number of mapping tools for visualizing violence against women exist, such as HarassMap and Map4Aid’s Fighting Violence Against

Women in India campaign, and text messaging is being used for a number of campaigns aimed at preventing domestic violence and violence against women. Take Back the Tech! is an effort mobilized during the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence that has developed various innovations in the use of SMS for public awareness campaigns.

Although the field is in its nascent stages, the time is ripe to begin building the evidence base for these tools and the lessons learned, with particular attention paid to the various cultural contexts. For example, some SMS campaigns to prevent domestic violence have actually backfired in some contexts because of the particular power and gender dynamics at the household level. This is an important element that often gets overlooked in the rush to deploy technologies, and it will be critical for the field to have more case studies seen through the prism of gender and power as it moves forward. Furthermore, the same technologies used for interventions can also help in evaluating these technologies. Data-collection tools used for health and human rights, such as the KoBo Project (KoboProject.org), provide open-source data-collection tools that also offer the encryption functionality that can protect users in conflict or human rights situations while also building the capacity of local organizations. Directories of these tools and case studies are in great need at the moment. Furthermore, the public health field itself can no longer afford to fall behind in its thinking about technology. Increasingly one’s ability to realize one’s capabilities, in the sense articulated by Amartya Sen, will require technological literacy that many in our field do not have. This emerging notion of technological citizenship (Barry, 2001) is likely to play a determining role in the social divides of the future as well as in the growing one within public health ranks, where new techno-political thinking is desperately needed.

William T. Riley, Ph.D.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health

The past decade has witnessed an explosion of mobile technologies. Eighty-three percent of U.S. adults own cell phones (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2010). Worldwide there are approximately 6 billion cell phone subscriptions, and the rapidly growing rates in developing countries, where wireless technologies have leapfrogged the wired infrastructure, have made it possible to reach people in remote villages and communities (ITU, 2011). The public health community has begun to leverage these mobile devices in order to perform real-time assessments and to intervene at the times when these interventions would be most useful (e.g., in the context of the behavior).

Despite the rapid growth of mobile technologies applied to health (mHealth), the evaluation of mobile technologies has not kept pace with the development and deployment of these technologies. Although there also needs to be considerable emphasis on the reliability, validity, and sensitivity of measurements in mHealth, the focus of this summary is on research evaluations of mHealth interventions.

Randomized Controlled Trials

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) is the standard for intervention research. Meta-analyses such as those performed by the Cochrane Review routinely include only RCTs in their reviews (Higgins, 2011). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations are developed predominately from the findings of RCTs (USPSTF, 2010). The Institute of Medicine relies heavily on RCTs as the basis for its consensus reports (IOM, 2011). Given the reliance on RCTs as the accepted standard for biomedical and behavioral evidence, mHealth interventions, including violence prevention programs delivered via mobile devices, need to be subjected to this same standard if they are to be accepted as a valid and effective method.

Appropriate Comparison Conditions in mHealth

One challenge of evaluating the efficacy of mobile interventions via RCTs is the choice of a comparison condition. How the mHealth intervention is intended to be used is an important consideration for determining an appropriate comparison condition. If the mHealth intervention fills a gap where no other viable intervention exists, then a no-treatment or usual care condition is appropriate. If the mHealth intervention is intended to augment an existing intervention, then an additive design in which the existing intervention is compared to the existing intervention plus the mHealth intervention would be used. If the mHealth intervention is intended to supplant or replace an existing low-tech equivalent interventions, then the low-tech intervention may be the appropriate comparison condition.

The comparison condition in which the mHealth intervention is intended to augment or supplant the existing intervention is a high outcome standard to exceed. One solution to this dilemma is to use or develop a minimal-contact version of the low-tech intervention (e.g., a self-help book or non-interactive Web pages) as the comparison condition, but this dilutes the effect of the low-tech intervention and often delivers it in a form that was never intended. Therefore, it becomes critical to ask in what way the mobile intervention is hypothesized to be better than the other interventions currently available. In many cases, it may not be the case that the mobile intervention is expected to produce better outcomes, but rather that it is