Important Points Highlighted by the Individual Speakers

• The undervaluation of tumor biomarkers reduces the use of diagnostic tests as well as incentives to develop evidence about their effectiveness.

• Eliminating the LDT pathway and submitting all genomic tests to a rigorous regulatory process could result in the generation of high-quality evidence regarding the analytical validity and clinical utility of all such tests.

• Venture capital companies are no longer investing in the development of molecular diagnostic tests because of the complexity in and lack of clarity for both regulatory and reimbursement pathways.

• A predictable and efficient pathway, not necessarily an easier one, from regulatory approval to reimbursement could help attract further venture capital investment in this space.

• Standards for molecular diagnostics could help establish widely accepted regulatory and reimbursement pathways that test developers can follow.

While reflecting their own viewpoints, two speakers framed much of the day’s discussion. Daniel Hayes, from the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, challenged the workshop participants to consider

a system in which all genomic diagnostic tests are approved through FDA rather than going through the LDT pathway. Sue Siegel, with the venture capital firm Mohr Davidow, said that venture capital funds are currently reluctant to invest in life sciences and health care start-ups, including molecular diagnostics, because of the continued lack of clarity surrounding the regulatory and reimbursement areas. Both speakers called for major changes in the regulation of genomic diagnostic tests to ensure that the field continues to move forward.

A CONSOLIDATED SYSTEM OF REVIEW AND APPROVAL FOR GENOMIC DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Oncologists overtreat probably 75 percent of their patients, according to Hayes, because they often do not know which patients are going to benefit from which therapies. “We treat everybody in the hopes that we’ll hit the ones that need it and will benefit. I tell my post-docs that luck is not a good strategy in golf or science. It’s nice to have when you get it, but it’d be really nice if we could focus our treatment on patients and not just hope that we get lucky.”

A bad diagnostic test for a tumor biomarker is as harmful as a bad drug, Hayes pointed out. He asked whether physicians would use a drug if they were not sure how it was mixed or what its concentration was, if they did not have clinical data about how the drug might be used, and if they did not have reliable clinical research data to determine how much efficacy it might have. “Of course not, but every day of the week we see patients whose treatment is being altered by tumor biomarkers in the absence of really good data to support that.”

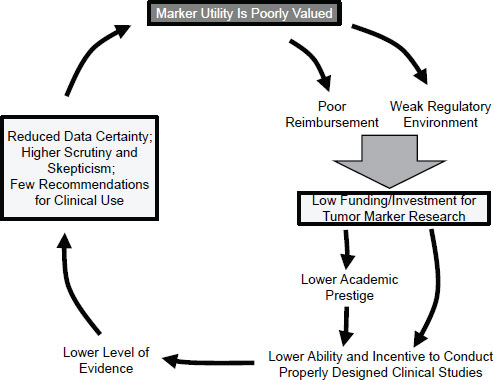

The basic problem is that there has been relatively little consistency regarding which biomarkers have been introduced into clinical practice. Very few cancer biomarkers with demonstrated clinical utility have been introduced over the past 30 years. Even among those tests that have been integrated into practice, their use in certain settings has not always been supported by evidence of benefit, such as the use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) as a screening test (Andriole et al., 2009), said Hayes. This has helped to create what Hayes has termed a “vicious cycle” in which tumor biomarkers are systematically undervalued (Figure 2-1). This undervaluation has led to limited use of these diagnostics by health care providers and poor reimbursement when a marker has been able to navigate the regulatory environment to be brought to market. Lack of use and reimbursement in turn leads to limited funding for biomarker research because the return on investment is low. The perception that markers have little utility has also led to an environment of lower academic recognition for developing biomarker-based tests. The overall result is reduced ability and incen-

SOURCE: Hayes, IOM workshop presentation on November 15, 2011.

tive to conduct properly designed clinical trials to generate high-quality evidence of clinical utility. In return, there is reduced data certainty, higher skepticism, and few recommendations for clinical use, said Hayes, which completes the cycle by contributing to the poor valuation of marker utility.

Hayes focused his recommendations for breaking the “vicious cycle” of undervalued tumor biomarkers on two areas: the regulatory environment and marker reimbursement.

Requiring FDA Approval of Laboratory Developed Tests

LDTs can currently be introduced into clinical practice while only meeting Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) laboratory standards (see Box 1-1). Such tests do not undergo formal reviews of analytical validity, clinical validity, or clinical utility (Box 2-1 and Table 2-1). Hayes recommended elimination of this pathway for market entrance and, instead, would require all diagnostic tests to undergo FDA review and

BOX 2-1

Definitions of Validity and Utility

During his presentation, Hayes offered definitions of analytical validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility adapted from Teutsch et al. (2009)

• Analytical validity: The assay accurately and reproducibly measures what it intends to.

• Clinical validity: The assay identifies a biological difference that may or may not be clinically useful.

• Clinical utility: Results of the assay lead to a clinical decision that has been shown with a high level of evidence to improve outcomes.

approval. Many commonly used tests would be removed if this were to occur, noted Hayes, especially in situ tissue-based tests, but it is not clear how many of these tests have analytical validity, clinical validity, or clinical utility, he said. While Hayes acknowledged that elimination of the CLIA pathway may be met with opposition from various groups and individuals, he also observed that “I can’t come up with a new drug in my [laboratory] as long as I only give it to my patients. That’s against the law, and I think it should be against the law to develop a new assay and use it to treat my patients differently without having had it vetted by some regulatory body.”

TABLE 2-1 Comparison of CLIA and FDA Regulatory Pathways

|

|

||

| CLIA | FDA | |

|

|

||

| Research Phase | No | Yes |

| Analytical Validation | Post hoc sampling | Yes |

| Clinical Validation | No | Yes |

| Report Adverse Events | No requirement; no system | Yes |

| Transparent Results | No public information | Published review summary |

|

|

||

NOTE: CLIA, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

SOURCE: Gutierrez, IOM workshop presentation on November 15, 2011.

A New Basis for FDA Approval

FDA approval of diagnostic tests is currently based on evaluation of intended use, analytical validity, and clinical validity. In advocating that FDA review and approve all diagnostics before they can be introduced into clinical practice, Hayes also recommended that a higher evidentiary threshold be met for diagnostic tests. Instead of including clinical validity and intended use in their assessment, he suggested that FDA should review diagnostics for analytic validity and clinical utility. While he acknowledged this will increase the time and resources needed to get FDA approval, tests will have demonstrated clinical value for patients upon entrance to clinical practice.

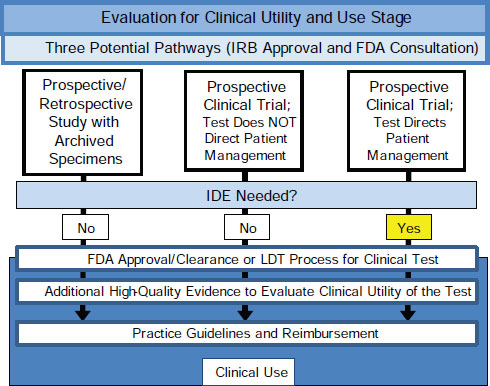

This change would require following one of three pathways for generating high-quality evidence of clinical utility, Hayes said (Figure 2-2). One is through a prospective-retrospective study using archived specimens from a clinical trial that can be used to specifically address the question being studied (IOM, 2011b; Simon et al., 2009). If archived specimens do

FIGURE 2-2 Three pathways for generating high-quality evidence of cliical utility.

SOURCE: As adapted from IOM, 2012.

not exist, evidence could be generated either through a prospective clinical trial where the marker does not direct patient management or through a prospective clinical trial where the marker does direct patient management. These three approaches would each generate high-quality evidence for the intended clinical use of a tumor biomarker test upon which FDA could base its review and approval or disapproval. This same evidence could then be used by technology assessment groups, practice guideline developers, and payers for decision-making purposes.

Hayes admitted that determining clinical utility is still somewhat like art: “I don’t know what it is, but I know it when I see it.” The results of the assay will need to lead to a clinical decision that has been shown with a high degree of evidence to improve outcomes. “For each circumstance, for each disease and for each assay, one needs to decide if it reaches what a group of clinicians would call clinical utility.”

Consolidate Reviews Within FDA

Currently, drugs are evaluated for safety and effectiveness in the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) while devices that are not linked to specific therapeutics are evaluated in the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). While CDER has established a standing Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) made up of experts in oncology and statistics, patient advocates, and other representatives to help review marketed and investigational cancer drug products, a similar approach has not been adopted by CDRH, according to Hayes. The center has enormous analytical expertise but weaker oncologic expertise. Instead of a standing board, ad hoc committees of experts without a “corporate memory” review devices, which means that “there is no consistent approach toward how one device is approved versus the other.” Hayes did note that while the ODAC has significant oncologic expertise it lacks analytical expertise and proposed combining the review of all oncologic products into a single FDA Oncology Office. Combining all oncologic products into a single office would require a fundamental reorganization of FDA, Hayes observed, which is a substantial obstacle to moving forward on this recommendation.

Basis for Reimbursement

Hayes recommended that reimbursement be based on the value that a tumor biomarker provides for clinical decision making as opposed to the cost of performing the assay. Cost-effectiveness analyses and comparative effectiveness research would be needed to demonstrate that the benefit to patients, society, and payers far outweighs the cost of a tumor biomarker

with demonstrated clinical utility. Third-party payers would need to provide reimbursements that recoup the increased costs associated with generating high-quality evidence of clinical utility. However, Hayes noted that health care providers also need to reform their practices and ensure they are properly using and ordering tests. “Third-party payers should have to pay for a test that has clinical utility, but shouldn’t have to pay for a test that is used in the wrong way.”

Overcoming Barriers

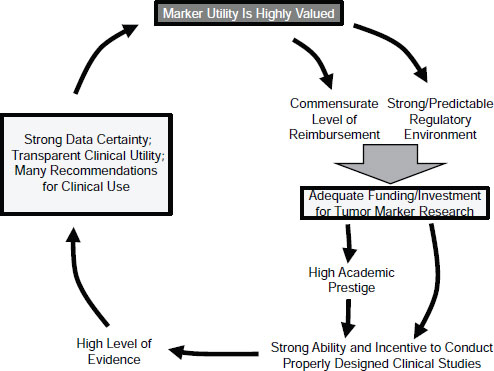

Overcoming the barriers to these recommendations will involve many stakeholders, including regulatory agencies, third-party payers, pharmaceutical companies and other commercial entities, physicians and other caregivers, patients and patient advocates, clinical guideline and technology assessment panels, academic centers and investigators, and research funding entities. These groups need to be “in the room talking to each other and working out the problems,” said Hayes. Together they could break the vicious cycle of undervaluation and create a virtuous cycle by introducing tumor biomarkers with high clinical utility (Figure 2-3), Hayes concluded.

PERSPECTIVE FROM VENTURE CAPITAL

Because of the complexity and uncertainty that currently surrounds regulation and reimbursement, the venture capital community is reluctant to invest in the development of molecular diagnostics, said Siegel. “We will continue to invest in the companies and their products that we currently are invested in, but the money is fleeing. Venture takes the early risk. Who is going to fill in when . . . venture capital is fleeing?”

Many earlier tests were developed with support from venture capital, including the Oncotype DX breast cancer assay for predicting chemotherapeutic benefit and metastasis risk, the MammaPrint assay for the risk of metastasis following breast cancer surgery, and the HER-2/neu test for directing Herceptin treatment of women with metastatic breast cancer.

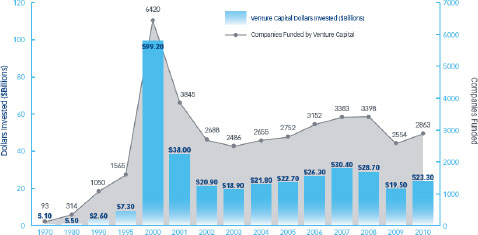

More broadly, Siegel observed, the venture capital community plays a crucial role in the economy, spurring innovation that benefits the quality and efficiency of the health care system. From 1970 to 2010, the amount of revenue generated by venture-backed companies was 21 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product. Approximately 12 million jobs in venturebacked companies led to $3.1 trillion in revenue. About three-quarters of biotechnology jobs are within companies that were originally venture-backed, and 80 percent of the revenue in biotechnology is generated from these companies.

SOURCE: Hayes, IOM workshop presentation on November 15, 2011.

The Venture Capital Process

Siegel gave a brief overview of the venture capital process. It begins with limited partners (LPs), who manage pools of money such as pension funds, retirement funds, endowments, or private wealth. LPs deploy these funds into different asset classes, of which venture capital is one. Venture capital tends to take the highest risk but in doing so also tends to get the highest rewards.

LPs fund general partners (GPs) who are investing in particular areas. The GPs deploy that money into entrepreneurs and companies, which provide products and services (Figure 2-4). As these companies grow, they generate assets that can be returned to the LPs. In this way, the LPs recoup their investments.

Siegel used her own firm as a more specific example. Mohr Davidow is a Silicon Valley venture firm that has existed for about three decades. It invests in three areas: information technology, clean technology, and personalized medicine. The firm bases its investment decisions on markets,

people, and technology, among other criteria, said Siegel. It tends to favor big problems that need solutions in big markets. As an early stage investor, the firm expects a life science or health care company to have a capitalefficient business model, to produce a product, and to be generating revenue within 3 to 5 years. It also prefers the company to have a strong intellectual property position, limited regulatory risks, a clear path toward reimbursement, and a convincing health economics model (a strong rationale for why a product could help the whole system of health care decrease costs).

With molecular diagnostics that are developed and brought to market under CLIA, venture capitalists can understand the risks and timelines required to grow a company and develop the tests as well as be able to predict with some confidence the potential returns, according to Siegel. Creating a company from inception with the purpose of developing and fully commercializing an LDT can take up to $100 million plus to get to a breakeven point, though some companies have managed to do it for $60 million to $70 million, “but they are more the exception than they are the rule.” To found a company with the purpose of developing an FDA-approved test would require somewhere between $100 million and $150 million of total capital invested to get the company to a breakeven point. Venture capitalists consider a return of only three times their investment into a company to be an unexceptional return. Therefore, a start-up company requiring $100M of total capital invested from its inception to develop and fully

FIGURE 2-4 Venture capital investments in U.S. companies from 1970 to 2010.

SOURCE: NVCA, 2011a.

commercialize a test needs to return at least $300 million within a fairly short timeframe to even meet what would be considered a modest return.

The Need for Clarity

The venture capital community is not asking for less stringent regulations. “We’re not here, as venture capitalists, to tell you don’t make it hard. We all want safe products,” Siegel said. “We’re here to ask you to make it clear, because without clarity we can’t assess the risk of knowing when to invest or when not to invest.”

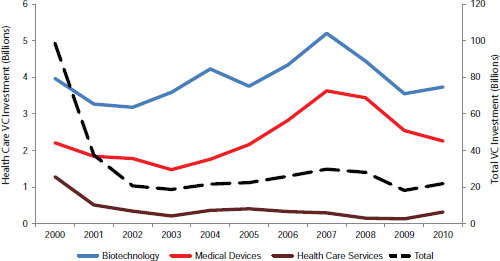

Regulatory and reimbursement uncertainty has contributed to a precipitous decline in venture capital investments in the life sciences and health care (Figure 2-5) and current trends point to future declines. In a survey of 156 venture capitalists about investing in the life sciences, 40 percent reported decreasing their life science investments over the past 3 years with an additional 40 percent planning to decrease their investments over the next 3 years (NVCA, 2011b). Sixty percent indicated that regulatory challenges are having the most impact on their investment decisions. Forty percent said that they planned to invest more in Asia and Europe. “Even though some regulations might be tougher [there], they’re clearer and [companies] know how to get reimbursed,” Siegel said. “Here in the [United] States, it’s not clear that we can get reimbursed for molecular diagnostic tests. So better predictability and increased efficiency [is needed].”

SOURCE: As adapted from NVCA, 2011c.

Reimbursement is currently a tougher obstacle than regulation, said Siegel. Companies cannot be sure whether their products will be reimbursed. Reimbursement has become “a truly Sisyphean effort,” and getting coverage decisions whether regional or national can be difficult, said Siegel. When drugs get through Phase III development, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) generally approves their reimbursement, but currently no such process exists for molecular diagnostics.

FDA and CMS also need to define the reimbursement pathway for molecular diagnostics. “What we’re asking for is a predictable and efficient roadmap from FDA to CMS. This allows private payers to then have a baseline to benchmark against,” said Siegel.

People in other industries such as the semiconductor industry have worked hard to develop standards to enable their products to move forward; the same needs to happen with molecular diagnostics. New approaches with companion diagnostics have been helpful, but much more progress is needed. In particular, said Siegel, the National Institute of Standards and Technology should be developing biological standards.

Siegel also pointed to the value of biological samples.1 She urged that a national repository with guidelines be put in place to allow for the accessing of biological samples so that studies can be done in a more standardized way.

The Consequences of Inaction

Without greater clarity, funding for innovation will dry up, job growth will slow, the transition of the health care system toward prevention and lower costs will not take hold, and national competitiveness will be eroded. “People are going elsewhere in the world to launch products or set up companies. It’s happening today. It’s happening pretty aggressively.” Even if patient advocate groups organize funding for the development of diagnostics, who will coach the entrepreneurs and help them develop their business plans and build their companies, asked Siegel.

Siegel urged that venture capitalists continue to be included at meetings on molecular diagnostics. “The more you educate us about what the decision process will be, the better the investment decisions we can make. This will allow venture capital firms to continue to support health care entrepreneurs who bring innovative ideas and business models that can help transform our current health care system into one that offers improved quality of care and increased access at lower costs.”

![]()

1 The Roundtable on Translating Genomic-Based Research for Health held a prior workshop on July 22, 2010, titled Establishing Precompetitive Collaborations to Stimulate Genomics-Driven Product Development, which examined the value, utility, and ethical challenges in using biospecimens in developing medical products, including diagnostics (IOM, 2011a).