Preparing for Population Aging in Asia: Strengthening the Infrastructure for Science and Policy1

Throughout most of the developed and developing world, one of the most daunting issues deals with the challenges raised by population aging. Rapid increases in life expectancy, especially at older ages, alongside unprecedented declines in fertility will soon lead throughout North America, Europe, and Asia to never before seen rates of population aging. The “problem” of population aging is easy to state—to provide income and health security at older ages and to do so at affordable budgets. All rapidly aging countries face similar risks, but Asian countries have some advantages and disadvantages. The disadvantages are that compared to Europe and North America, Asian countries are now aging more rapidly at lower incomes with weak nonfamilial income and health security systems in place. The big advantage is that it is much easier to change public systems in Asia than in Europe and America where the vested interest around the status quo has proven to be a major impediment to any policy adjustment.

Until recently, the one shared disadvantage throughout America, Europe, and Asia is that a scientific data infrastructure was not available that would inform simultaneously in one common platform about the status of key life domains at older ages—work, economic resources, health status and healthcare, the role of the family, and cognition. With-

____________

1 A presentation based on this paper was presented in New Delhi, India, in March 2011. This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging in the United States.

out that type of data infrastructure, we would not be able to monitor the key simultaneous transitions in these domains as people age and, even more importantly, how the various life domains mutually influence each other. The implication is that we would be unable to anticipate unforeseen consequences of policies centered on one domain in isolation on major life outcomes in the other domains. The absence of a common data infrastructure platform also implies that countries would not learn from the successes and failures of other countries in their attempts to deal with population aging.

Fortunately, this situation is rapidly changing for the better. Starting in the United States with the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a data infrastructure platform has emerged that has spread throughout Europe and Asia centered on issues of population aging. In this chapter, I describe the origins and world-wide spread of this data infrastructure, its common elements, and its potential to inform policy and enhance the science.

This chapter is organized into three sections. The next section describes the primary demographic trends driving aging in several Asian countries over the next century. Section 2 summarizes the new aging data sets that are based on the U.S. HRS, with discussion on the European and Asian comparable surveys that have emerged to provide a scientific and policy infrastructure to study population aging around the world. Section 3 provides illustrations of the way these surveys can be used to study population aging. The final section also highlights the chapter’s main conclusions.

DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS IN ASIA

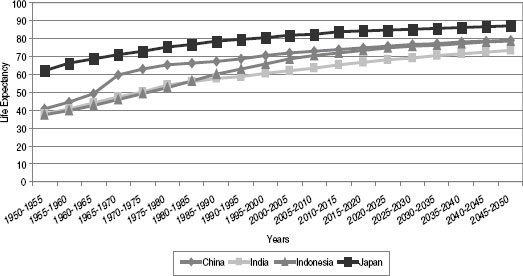

There are several fundamental demographic trends that are rapidly changing population aging throughout the world, and Asia is no exception. Figure 2-1 highlights one of the forces contributing to the aging of the Asian population by plotting changing life expectancies for four large Asian countries—China, India, Indonesia, and Japan—over a 100-year period from 1950 to 2050. In 1950, average life expectancy was around 30 years in China, India, and Indonesia, but over the subsequent 60 years until the present time, life expectancy in all three countries improved dramatically—to around age 70 in China and Indonesia and over age 60 in India. While Japan started at a higher base with more than a 60-year life expectancy in 1950, Japan, too, experienced large drops in mortality, reaching a life expectancy in the mid-80s by 2010, one of the highest life expectancies in the world. Nor is there any sign of much abatement in these trends. The best demographic projections foresee additional added years of life in all four countries in the future, with China and Indonesia both reaching life expectancies of about 80 years, double the level that existed 100 years earlier.

FIGURE 2-1 Average life expectancy at birth in four Asian countries, 1950-2050.

SOURCE: Chinese Academy of Sciences et al. (2010).

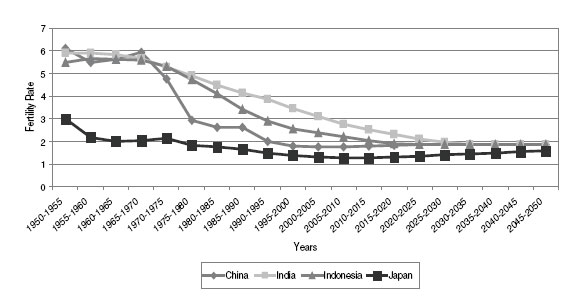

The second and far more important driving demographic force in Asian population aging is trends in fertility, which are plotted in Figure 2-2. Using 1950 once again as the starting point, average fertility in China, India, and Indonesia was around six children per woman. The subsequent fertility declines in all three countries were so dramatic that they are now below replacement levels in all three. The speed of the decline was more rapid in China, no doubt due to the one-child policy in that country, although the endpoint suggests that this decline would have happened there anyway, even if not at the same speed. As the most developed of the four countries at the start of the comparisons, the size of change in fertility in Japan was smaller than the others, but even there, fertility has been cut in half.

While declining mortality and especially fertility contribute to population aging by making populations on average “older,” it is important to keep in mind that both of these fundamental causes of population aging represent enormous progress in the human condition in these Asian countries. The extension of life and the decline in fertility are very beneficial trends driving population aging around the world and especially in Asia that lead to significant improvements in the human condition.

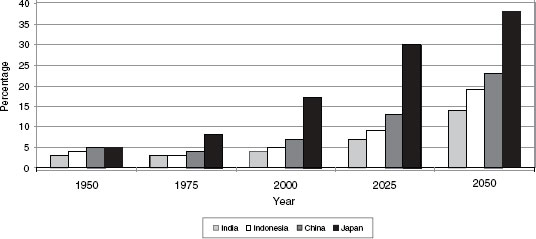

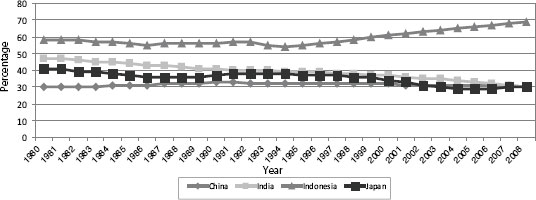

At the same time, population aging raises some important challenges in maintaining a good life for older people in these countries as they attempt to maintain income security and lower health risk at older ages. Our first look at the underlying demographics of these challenges is provided in Figure 2-3, which lists the changing fractions of the population in the four countries who are at least 65 years old. In 1950, this fraction

FIGURE 2-2 Changing total fertility rate per woman, 1950-2050.

SOURCE: Chinese Academy of Sciences et al. (2010).

FIGURE 2-3 Percentage of population aged 65 and older, 1950-2050.

SOURCE: Chinese Academy of Sciences et al. (2010).

was 5% or lower in all four Asian countries. Using this metric, change was slow until the end of the 20th century in all countries except Japan, where the fraction rose to about 18 percent. In the first half of the 21st century, the pace of change will be dramatic with about one-third of the Japanese population over age 65 and with rates of about one in five in Indonesia and China. Population aging is slower in India over this time period, but this is mostly due to using the other three countries as the comparison group.

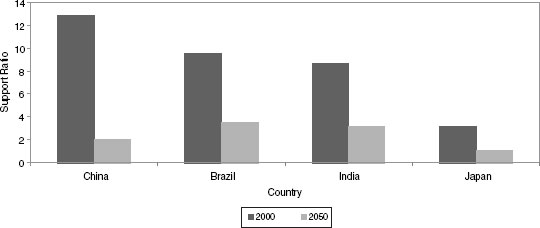

Figure 2-4 expresses the consequences of population age in terms of aging support ratios. For each country for the years 2000 and 2050, this

figure measures the number of workers (those in the age groups 25–64) relative to the number of people aged 65 and older. Taking China as the first example, the dramatic change across a relatively short 50-year time period is evident. At the turn of this century, there were more than 12 potential Chinese workers for every person over age 64. By the year 2050, the ratio will be about two to one. Similar trends are evident in Indonesia and India. While Japan was already well into the population aging process in 2000, the subsequent change still gives one pause, as Japan reaches a position in the year 2050 where there is about one worker for every retired person.

One potential avenue of adjustment to population aging is to delay retirement and to work to older ages. However, the data on male labor force participation rates in Figure 2-5 indicate that many men are already

FIGURE 2-4 Support ratios (people aged 25-64/65 and older).

SOURCE: Data from United Nations (2008).

FIGURE 2-5 Percentage of labor force participation among men aged 65 and older, 1980-2008.

SOURCE: Chinese Academy of Sciences et al. (2010).

working at these ages (more than 60% in Indonesia), and with the exception of Indonesia, trends over time are either stagnant or show declining male labor force participation rates.

THE NEW DATA INFRASTRUCTURE FOR POPULATION AGING

The world will continue its rapid rate of population aging, which raises challenges for many countries. New institutions and new programs must be implemented and evaluated to determine whether the dual goals of providing income and health security at older ages can be achieved at affordable budgets. In response to that challenge, a set of harmonized data sets have evolved in the last 20 years to document in detail the changing health, economic status, and family relations of older populations. This set of surveys also is now in place to attempt to monitor the impacts of any new health and retirement programs and policies that may affect incentives of the older population on whether they continue to work, how they obtain their health care and whether it is effective, and whether they are able to achieve adequate incomes.

The Health and Retirement Study

The first of these studies was the Health and Retirement Study in the United States. The HRS was originally conceived as a panel study of those 51-61 years old in 1991 using a two-year periodicity to monitor the economic (especially retirement) and health transitions (especially into poorer health) in the subsequent years and the manner in which these economic and health domains mutually influence each other at older ages.2 The scope of the study has expanded significantly in the subsequent 20 years, in part by adding older and younger birth cohorts so that the HRS now attempts to be continuously population representative of Americans at least 50 years old.3

The key innovation of the HRS, which has been adopted in HRS-type surveys in the rest of the world, is that it broke with the tradition of other surveys that focused almost entirely on the concerns of a single domain of life and were run by a single academic discipline. For example, many countries had good economic surveys dealing with work and income, other excellent surveys specializing in health outcomes and/or healthcare

____________

2 The HRS has been primarily funded by the Division of Behavioral and Social Research (BSR) at the National Institute on Aging, with significant supplemental funding from the Social Security Administration.

3 See Juster and Suzman (1995).

utilization, and demographic surveys concentrating on the role of the family. These are all key life domains and worthy of study.

But this separation is based on an implicit and false premise that these life domains are independent of each other and that understanding behavior in one domain can be achieved without knowing very much about the others. This is not how people organize their lives anywhere around the world. Health can affect the ability to work and earn income; economic resources can help families deal more effectively with illness, especially of the old; and the family is a primary resource in many countries for ensuring the well-being of the elderly. The rigid separation of life domains of family, economics, and health was often reinforced by the equally rigid separation and ownership of domains and surveys claimed by the academic disciplines. This was no easy issue to resolve, but from the very beginning the HRS was governed and implemented as a multi-domain and multidisciplinary survey.

By now, the substantive content of HRS covers the following broad range of topics—health (physical/psychological self-report, conditions, disabilities; cognitive testing, health behaviors [smoking, drinking, exercise]); health services (utilization, expenditure, insurance, out-of-pocket spending); labor force activity (employment status/history, earnings, disability, retirement, type of work); economic status (income, wealth, consumption); and family structure (extended family, proximity, transfers to/from of money, time, housing). In addition to personal interviews, linkages are also provided to pension, Social Security earnings/benefit histories, and Medicare usage and expenditures. Interviews were conducted with both partners/spouses in a household about their own lives and with the more knowledgeable of the two about their joint lives. This substantive template served as the model for all the other international aging surveys to follow.

One marker of the HRS’s eventual success and its adoption in other countries is its exponential growth in scientific productivity. By June 2010, there were about 1,700 papers written using the HRS—932 published in academic journals, 127 book chapters, 193 dissertations, and 445 working papers. The number of papers based on the HRS has more than doubled since the HRS’s 10th birthday in 2001, with a 45% growth in HRS papers since 2005.4 These publications were written by scholars from many disciplines and were published in the leading journals in health, economic, and demographic journals.

____________

4 I thank David Weir of the University of Michigan and the current principal investigator of the HRS for these numbers.

The International Landscape in Comparable Data Collection—Before Asia

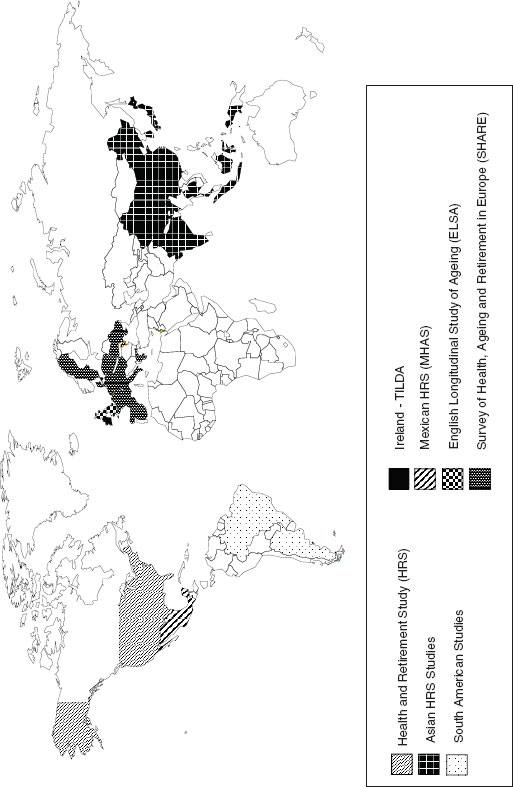

Another metric of its success is that the HRS has spawned 24 other international surveys that share a common scientific and policy mission with a mutual desire to harmonize some of their main survey content. HRS sister surveys currently include the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) in Mexico, English Longitudinal Survey of Ageing (ELSA) in England, the Irish Longitudinal Study of Ageing (TILDA) in Ireland, 15 countries in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) network, and six surveys in Asia—Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) in Indonesia, Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA) in South Korea, Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) in China, Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) in India, Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Thailand (HART) in Thailand, and Japanese Study on Aging and Retirement (JSTAR) in Japan. Below, I first briefly describe the Mexican and European surveys in the network, followed by those in Asia.

The first country follow-up to the HRS was the Mexican Health and Aging Study, which was fielded in 2001 with a follow-up in 2003. MHAS is a prospective panel study of health and aging in Mexico. The baseline survey includes a nationally representative sample of Mexicans aged 50 and older and their spouse/partners regardless of their age. Areas covered include health behavior and health status, childhood and family background, migration history, sources and amounts of income, and housing environment. The MHAS was suspended after its second round due to lack of funding, but new funding was obtained in 2011 and a third round of the panel and a new baseline are in the planning stages.

A decade after the HRS started, the second country to follow up on the HRS model was England with the English Longitudinal Survey of Ageing. ELSA was designed to collect longitudinal data on health, disability, economic circumstances, social participation, and well-being, from a representative sample of the English population aged 50 and older (http://www.ifs.org.uk/elsa/). The initial sample for ELSA in 2002 was drawn from three years of the Health Survey for England (HSE): 1998, 1999, and 2001. Interviews were carried out with 11,391 individuals, and new cohorts have been subsequently added to keep it representative of the English population aged 50 and older. Operating on a two-year periodicity like the HRS, ELSA has now completed five waves of data collection.5

In most respects, ELSA’s measurement of socioeconomic status (SES)

____________

5 For more details on ELSA, see Marmot et al. (2003).

and health closely parallels that in the HRS, and ELSA also links to administrative records. The major ELSA innovation was to take biological measures from venous blood in every second wave. These biological measures included markers such as fibrinogen (which controls blood clotting and is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease [CVD]), HbA1c (a test for diabetes), C-reactive protein (CRPC—measuring the concentration of a protein in serum that indicates acute inflammation and possible arthritis), and cholesterol. Such measures can be used to validate respondents’ self-reports and to monitor overall health. They also can inform about pre-clinical levels of disease of which respondents may not have been aware and to which they have not yet able to react behaviorally. The power of this innovation is probably best documented by the adoption of biomarkers in subsequent waves of the HRS. This attribute within the HRS network of allowing scientific innovation at the country level and having others within the network adopt the more successful innovations is one of the gains from the network’s close partnerships.

The Survey of Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe is a multidisciplinary and cross-national panel interview survey on health, SES, and social and family networks of individuals aged 50 and older in continental Europe. The original 2004/2005 SHARE baseline included nationally representative samples in 11 European countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland) (http://www.share-project.org/). For these countries, a second wave of data collection took place in 2006, and a third wave collecting a retrospective wave documenting prior life experiences took place in 2008. The fourth wave of data collection was scheduled for completion in 2011. Once again, the SHARE instruments are similar to those in the HRS and ELSA. SHARE’s big innovation is an insistence on very strict comparability of survey instruments within the SHARE countries.

The latest addition in the European network of aging surveys is The Irish Longitudinal Study of Ageing, which completed its baseline field work in spring 2011 (http://www.tilda.tcd.ie). Like the other surveys in the North American-European network, TILDA was meant to be population representative of the Irish population aged 50 and older, and has a two-year periodicity for its follow-up rounds to chart health, social, and economic circumstances of the Irish population.

Like other surveys in this network, TILDA includes its own version of scientific innovation. In addition to completing a computer-assisted personal interview, most TILDA respondents agreed to visit a Health Assessment Centre in one of two cities—Dublin and Cork—where appropriate medical measurement facilities are available to take detailed physical measurements especially related to disability and functioning (gait assessment and balance), cognition, macular degeneration, and cardiovascular

health (heart rate variability, pulse wave velocity, phasic blood pressure) and to provide biomedical samples. It remains to be seen how many of these TILDA innovative measures will be judged to be sufficiently cost-effective to transfer to some of the other studies in the network.

The International Landscape in Comparable Data Collection—On to Asia

The successful implementation of the HRS model in Western Europe was soon followed by similar efforts in six Asian countries—China, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand. While overall comparability with the HRS model was maintained, several changes were made to reflect the reality of the Asian context. This reflects the general principle in this network that while it is important to have significant comparable content so that cross-national studies can be conducted, the content has to reflect the reality and policies of each country.

One of those changes was that in many of the Asian countries, the age cutoff for participation in the survey was moved down five years to age 45. The reason for this was two-fold—in developing countries such as China, India, Indonesia, and Thailand, the transition into poorer health starts at younger ages than in Western Europe and the United States. Second, in some of these countries, such as China, at least in the formal wage and government sectors, rules for mandatory retirement often take place at younger ages than in Western Europe and the United States. Third, due to the central importance of local communities in many Asian countries not only in providing healthcare and income security but also in organizing social life, many of the Asian countries appended community surveys to the respondent interviews. Another change discussed in more detail below is that in order to accurately measure the economic domain in countries with sectors where economic activity is largely nonmonetarized, it is necessary to take a broader view by including modules that measure income, assets, and consumption.

The Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing is a longitudinal survey of the Korean population aged 45 and older who reside in a community. The baseline survey instrument was modeled after the HRS, using an internationally harmonized baseline survey instrument with the following core content: demographics; family and social networks; physical, mental, and functional health; health care utilization; employment and retirement; and income and assets. The baseline wave was collected in 2006, and two subsequent follow-ups have been conducted.

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) is conducted by the China Center for Economic Research (CCER) at Peking University. It is a survey of households with members aged 45 years and

older, plus their spouses. Given the complexity of doing a survey at the national level in China, a pilot was conducted in 2008 in two provinces, Gansu and Zhejiang (Zhao et al., 2009). Zhejiang, located in the developed coastal region, is one of the most dynamic provinces in terms of its fast economic growth, private sector, small-scale industrialization, and export orientation. Gansu, located in the less developed western region, is one of the poorest, most rural provinces in China.

The pilot survey collected data from 95 communities/villages in 32 counties/districts, covering 2,685 individuals living in 1,570 households. The CHARLS pilot survey experience was very positive. The overall response rate was 85%, with 79% in urban areas and 90% in rural areas. Given the importance of community in the everyday life of older Chinese people, the community questionnaire focuses on important infrastructure available in the community, plus the availability of health facilities used by the elderly and on prices of goods and services often used by the elderly. The 2008 pilot data are now available publicly (http://charls.ccer.edu.cn). The baseline national wave of CHARLS was fielded from June 2011 to March 2012, with a second wave fielded in 2013. This national survey will include about 10,000 households and 17,500 individuals.

The Panel Survey and Study on Health, Aging, and Retirement in Thailand was developed in 2008. The first stage was a pilot baseline survey of 1,500 household samples, which was conducted during August–October 2009 by interviewing, face-to-face, one member aged 45 and older from each household. HART was conducted in two sampled areas: Bangkok and its vicinity, and Khon Kaen Province. A second pilot panel survey of the same households was conducted in 2011 with research funding from the Thailand National Higher Education Commission. The survey instrument was an adaptation of that of KLoSA with some adjustments to fit local conditions. The principal investigators have applied for a grant for a national longitudinal study on aging with the first baseline survey in 2012.

The Japanese Study on Aging and Retirement is a panel of community-residing older Japanese adults. The baseline sample includes more than 4,200 Japanese aged 50 to 75. JSTAR was designed to capture the same key concepts of the HRS, and particularly those similar to SHARE. JSTAR added a self-completion questionnaire to collect data on food intake. JSTAR’s sampling design is distinct from that of the others in the HRS survey network in that it represents selected municipalities and not the nation as a whole. This design was chosen because many key policy decisions about the Japanese elderly (healthcare and retirement) are set at the municipal level. This design facilitates an examination of policy differences across municipalities, and these municipalities granted permission for links with very good administrative data. The first JSTAR wave,

conducted in 2007, used a sample of five municipalities with linkage to health expenditure records. Two municipalities were added in the second wave, and more municipalities will be added in the future.

LASI is an internationally harmonized panel survey representing the elderly population in India. The LASI pilot study sample of about 1,500 persons was drawn from four states (Karnataka, Kerala, Punjab, and Rajasthan) and was successfully completed in the spring of 2011. A full-scale, biennial survey of 30,000 Indians aged 45 and older is planned for 2012, with follow-ups every two years. The survey instrument includes the same core contents as the HRS. Other innovations of LASI include collecting data on physical environment and new questions on health utilization behaviors relevant to a developing country context, ranging from hospitalization to traditional healers, as well as new methods to measure social connections and expectations.

The first wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS1) was conducted in 1993–1994 covering about 83% of the Indonesian population living in 13 of the country’s 26 provinces. IFLS2 followed up with the same sample four years later, in 1997–1998. One year after IFLS2, a 25% subsample was surveyed to provide information about the impact of Indonesia’s economic crisis. IFLS3 was fielded on the full sample in 2000/2001 and IFLS4 in 2007/2008.

Originally, IFLS covered the full age distribution of the Indonesian population, but by following the same individuals over time, it has become another aging survey. For example, by IFLS4, 40% of the original IFLS1 household population were 40 years old and older.6 In addition, as the population of the sample aged, the content of IFLS changed so that it was comparable with the other Asian aging surveys. In combination, the four waves of IFLS span a 14-year period of dramatic social and economic change in Indonesia and provide detailed longitudinal data on individuals, households, and communities that will greatly enhance the study of adults 45 years and older.

Figure 2-6 shows the worldwide spread of the HRS model of aging surveys around the world. Many countries on three continents—North America, Europe, and Asia—now have HRS-type international surveys.7 What accounts for this spectacular success in the HRS network of surveys, including their Asian counterparts? One reason, of course, was that the time was ripe given its central motivating issue—population aging. The world is getting older, and new institutions and policies are needed

____________

6 Details of sampling and field procedures can be found in User’s Guides, which are publicly available at http://www.rand.org/labor/FLS/IFLS.

7 This year, an HRS-type survey has been funded in Brazil, and a pilot is planned for early 2012, so a fourth continent is about to be added.

FIGURE 2-6 HRS-type surveys around the world.

to continue to provide income security and protection from increasing health risk and to do so at sustainable budgets—a long way from the current situation. While the scientific moment was seized, that is often not enough. Competence in execution certainly played a role, and the research teams leading all these studies deserve a lot of credit.

While all these factors were important, they were not enough. I believe that a central reason for success is the network’s model of inclusion and openness, especially when it comes to cooperation, listening to, and implementing good scientific ideas. Openness is reflected most directly by the public release of all data in the network of surveys. Its openness also deeply reflects the perspective of the primary funding agency for these HRS surveys—the Division of Behavioral and Social Research (BSR) at the National Institute on Aging and, in particular, its leader, Dr. Richard Suzman. BSR has also provided critical start-up funding for many international surveys and continues to co-fund many of them. While the HRS international network has maintained its core focus on the domains of economics and health, its scientific scope has steadily expanded with significantly improved measurement of cognition, psychosocial risk factors, biomarker-based measures of health, and relevant dimensions of the community These domains were seen not only as important in older populations around the world, but also central in understanding the critical health and economic decisions that older people must make.

MEASUREMENT IN ASIA

Measuring Health Domains in Asia

One of the great difficulties in measuring health status in most Asian countries is that one cannot rely only on self-reports of respondents. As mentioned before, even some of the HRS surveys in North America and Europe have moved to including biomarkers in their measurement protocols. This is even more critical in developing Asian countries that are characterized by widespread undiagnosed diseases, including hypertension and diabetes, and low awareness of health problems. For example, in Indonesia, 71% of men who are hypertensive are undiagnosed. Similar rates apply in China, India, and Thailand for both hypertension and diabetes. In addition, biomarkers such as blood pressure and cholesterol level may indicate preclinical levels of disease that may not be known to respondents.

Because of this, many of the Asian surveys have included both biomarkers and performance tests in their survey protocols. The value of collecting biomarkers related to these health outcomes in population surveys has become widely recognized (Crimmins and Seeman, 2004). If

we use CHARLS as an example, its biomarkers will now include systolic and diastolic blood pressure (measured three times) and pulse rate, all indicators of cardiovascular disease. Venous blood samples will be taken to measure HbA1c (a test for diabetes), total and HDL cholesterol, hemoglobin (low hemoglobin is a measure of anemia), and C-reactive protein (a measure of inflammation).

In addition to body mass index (BMI), CHARLS collects data on height, lower leg length and arm length (from the shoulder to the wrist), waist circumference, grip strength, lung capacity measured by a peak flow meter, and a timed sit to stand. Waist circumference can be used to indicate weight and adiposity. Researchers have argued that it is not obesity per se but the distribution of adipose tissue that is related to increased risk (Banks et al., 2011).

Measuring Economic Domains in Asia

Unlike many HRS-type surveys in industrialized countries, the measurement of economic resources in developing countries, where a good deal of productive economic activity is not monetized, is more complex. Many people in these countries work in family shops or farms where their labor is not directly compensated but shows up instead in the shared consumption of the household. Relying on the HRS-ELSA-SHARE-TILDA economic modules, which are based almost entirely on the receipt of money for work, would result in a substantial mischaracterization of the economic resources available and especially their distribution across households.

Fortunately, the IFLS had already pioneered the development of household consumption modules that appear to work very well and do not take inordinate amounts of survey time. Following this model, both CHARLS and LASI in their economic modules measured income, wealth, and consumption expenditures.

The importance of this comprehensive measurement of economic resources is seen in Table 2-1 using data from the 2008 CHARLS pilot survey.8 This table displays the distribution of household income, household wealth, and household consumption of CHARLS individuals. The final two rows display two measures of inequality in the distribution of resources among CHARLS pilot respondents. If conventional income measure is used, inequality appears to be enormous—those in the 90th percentile have 334 times as much income as those at the 10th income percentile. Inequality appears to be even more widespread if household

____________

8 I am grateful to Professor Shen Yan of CCER at Peking University for providing this data. For more details on these issues, see Park et al. (2012).

TABLE 2-1 Comparisons of Distributions of Income, Wealth, and Consumption in China

| Percentile | Household Income | Household New Wealth | Household Expenditure |

| 90 | 25,182 | 230,745 | 15,607 |

| 75 | 14,704 | 77,569 | 10,559 |

| 50 | 5,626 | 30,469 | 5,781 |

| 25 | 1,289 | 4,792 | 3,314 |

| 10 | 75 | 26 | 1,747 |

| 90/10 | 334.3 | 8,963.1 | 8.9 |

| 75/25 | 11.4 | 16.2 | 3.2 |

SOURCE: Data from CHARLS pilot.

assets are used instead—almost 9,000 as many assets at the 90th wealth percentile compared to the 10th. However, when the most comprehensive and appropriate measure of availability of economic resources is used—household consumption—the ratio of the 90th to the 10th percentile is only 8.9. Nine-to-one still indicates considerable inequality within the Chinese population, but income and wealth measures significantly distort the amount of economic inequality. They may also distort trends over time when economic development is typically associated with monetizing economic activity, especially among the less well-to-do, so that inequality based on either income or assets will appear to be falling only due to monetization.

These surveys are also unique in separately measuring income and assets at the individual level (for respondents and spouse) as well as at the household level. The advantage of doing so is that who in the household controls the economic resources may matter in how those resources are used. For example, in an analysis of the Indonesian economic crisis of the late 1990s, Frankenberg, Smith, and Thomas (2003) showed using the IFLS that women’s unique ownership of certain assets, including jewelry, smoothed consumption and protected the welfare of children.

Monitoring Change over Time

One of the benefits from these new sets of aging surveys is that they will provide a platform to monitor on a comparable basis the changes that take place in the future in this set of Asian countries. Given how dynamic the countries are, change will be the order of the day, but all changes may not be positive. CHARLS, HART, KLoSA, and LASI are too new to see that benefit, but the 20-year-old IFLS can illustrate the potential. For example,

based on research using IFLS, it can be shown that smoking behavior among adult men has scarcely changed over those 20 years. Similarly, while the fraction of men who were undernourished (BMI < 18.5) was almost cut in half between 1993 and 2007 (from 17.5% to 9.5%), conferring a health benefit to the Indonesian population, the fraction of men who were overweight rose sharply over the same time period (from 6.5% to 10.4%), raising a signal of an impending health risk.9

Perhaps, the future use of these aging surveys is best illustrated by their ability to monitor the impacts of the Asian financial crisis in Indonesia. When IFLS began in the early 1990s, there was little talk of a financial crisis in the future. The second wave of IFLS was fielded in 1997, a year before the still-unanticipated financial crisis. Then, decades of economic growth in Indonesia were abruptly interrupted in 1998. In early 1998 the currency collapsed, falling four-fold in just a few days, while real wages declined by some 40% in the formal wage sector.

The immediate effects of the Asian crisis on the well-being of Indonesians are examined using IFLS. Frankenberg, Smith, and Thomas (2003) showed that families adopted several mechanisms in response to the crisis. Some families consolidated their living arrangements by moving in with relatives in low-cost locations, labor supply increased, spending on semi-durables fell while spending was maintained on food, and, especially in rural areas, wealth, particularly gold, the price of which was rising, was used to smooth consumption. The impact of the crisis was not widely reported as most severe on the poor, but rather on the more well-to-do who worked in the formal sector. This episode highlights the value of ongoing longitudinal surveys that can be put into the field very rapidly and provide basic scientific evidence to help understand the effects of major innovations on well-being and behaviors in society.

CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE INTERNATIONAL HRS SET OF AGING SURVEYS

There is by now sufficient time to assess the primary lessons learned from these aging surveys and why they have been so successful. First, and perhaps most importantly, the data must be placed into the public domain in a reasonable time frame, usually less than a year. The full set of HRS international surveys have adhered to that principle, with the Asian surveys often among the most exemplary. Before this, the tradition in many of the Asian countries in this network was very much the opposite, with negative consequences for the advancement of science and policy for social scientists within these countries. Data were tightly guarded and not

____________

9 For more details on these issues, see Witoelar et al. (2012).

distributed even to host country scientists. Most of the scholars in these Asian countries had little data to analyze at all and turned instead to the more readily available American or European data. In the end, breaking the tradition of hoarding data and making the default option widespread public release may be the most important scientific impact of the HRS international aging surveys in Asia.

Second, the most common and most important studies will be conducted within a single country, dealing with the key scientific and policy issues within each country separately. Policies on population aging will be made on a country-by-country basis. Understanding patterns of behavior on retirement, healthcare, and the role of the family within countries is a prerequisite for learning from good comparative work. But there will be an important role for comparative studies, since it is much easier to step out of the conventional wisdom box constrained by country specific policy and science.

Third, the network of researchers around the world who have become an integral part of the development and diffusion of these HRS sets of international surveys is in many ways as important a scientific development as the creation of the data. This network of scholars starts with the survey developers and founders, but it has quickly spread to their students and collaborators within these countries. It now numbers in the thousands, spawning collaboration among scientists around the world who barely knew each other five years ago.

Fourth, while it is critical to maintain core principles, these studies must also be willing to evolve and grow with the science. The HRS is an excellent example. The core principles of merging the main health, family, and economic domains of life into a single platform remain, but the HRS is a very different study today than it was in 1992. Significant substantive additions have been made in cognition, key biomarkers, and the potential to do genetic studies, measuring well-being and dimensions of personality. The HRS has also responded to some of the major policy initiatives in the United States by introducing modules that have enabled the monitoring of the impact of key policy changes in healthcare use and expenditures. As new policy initiatives emerge in the Asian countries in this network—which happens at much greater frequency than in the United States—the Asian surveys should respond and become a major platform for monitoring and evaluating the impacts.

REFERENCES

Banks, J., M. Kumari, J.P. Smith, and P. Zaninotto. (2011). What explains the American disadvantage in health? The case of diabetes. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 66(3):259-264.

Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Indian National Science Academy, Indonesian Academy of Sciences, National Research Council of the U.S. National Academies, and Science Council of Japan. (2010). Preparing for the Challenges of Population Aging in Asia: Strengthening the Scientific Basis of Policy Development. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Crimmins, E.M., and T.E. Seeman. (2004). Integrating biology into the study of health disparities. Population and Development Review 30:89-107.

Frankenberg, E., J.P. Smith, and D. Thomas. (2003). Economic shocks, wealth, and welfare. The Journal of Human Resources 38(2):280-321

Juster, F.T., and R. Suzman. (1995). An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. The Journal of Human Resources, Special Issue on the Health and Retirement Study: Data Quality and Early Results 30:S7-S56.

Marmot, M., J. Banks, R. Blundell, C. Lessof, and J. Nazroo. (Eds.). (2003). Health, Wealth, and Lifestyles of the Older Population in England: ELSA 2002. London, England: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Park, A., Y. Shen, J. Strauss, and Y. Zhao. (2012). Relying on whom? Analyzing how Chinese elderly finance their consumption. Chapter 7 in Aging in Asia: Findings from New and Emerging Data Initiatives. J.P. Smith and M. Majmundar, Eds. Panel on Policy Research and Data Needs to Meet the Challenge of Aging in Asia. Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

United Nations. (2008). World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

Witoelar, F., J. Strauss, and B. Sikoki. (2012). Socioeconomic success and health in later life: Evidence from the Indonesia Family Life Survey. Chapter 13 in Aging in Asia: Findings from New and Emerging Data Initiatives. J.P. Smith and M. Majmundar, Eds. Panel on Policy Research and Data Needs to Meet the Challenge of Aging in Asia. Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Zhao, Y., J. Strauss, A. Park, Y. Shen, and Y. Sun. (2009). Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, Pilot. Users Guide. National School of Development, Peking University.