Facilitating Longer Working Lives: The Need, the Rationale, the How1

The theme of this paper is that social and economic choices in societies must adjust as the age structure of the population changes. In particular, some of the bounty of longer lives must be allocated to prolonging the labor force participation of older workers. The changing demographic environment over the past four or five decades represents both an achievement and a problem. Mortality rates have declined and life expectancy has increased substantially in industrialized and developing countries. This is the achievement. What is the problem? Declining birth rates and fewer young people, together with longer lives, have meant that

____________

1 This is a written version of a paper presented at the conference on the Challenges of Population Aging in Asia: Strengthening the Basis of Policy Development, held in Beijing, December 9-10, 2010. A very similar paper was also presented at the Collogue sur l’Emploie des Seniors, organized by DARES, and held in Paris, October 14, 2010. The paper relies heavily on the International Social Security Project that I direct with results based on analyses by research teams in 12 countries. In particular, I draw freely from the preliminary summary of the most recent phase of the project (Milligan and Wise, 2011), the summary of the prior phase of the project (Gruber and Wise, 2010), and the summary of the first phase of the project (Gruber, Milligan, and Wise, 1999). This paper also compares many of the key results with results for China, and I wish to thank Wei Huang from Peking University for providing these data. The International Social Security Project has been funded by the National Institute on Aging through grants P01 AG005842 and P30 AG012810 and by the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) via Inter-Agency Agreement Y3-AG-0725. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Social Security Administration. I have also benefited from the comments of two reviewers of the paper and from the comments of the volume facilitators.

the proportion of old to young is increasing. As the number of older people increases, health care costs will rise, both because of the increase in the number of older people but also because advancing technology will likely create better and perhaps more expensive health care treatments. The cost of public pension (social security) programs will also rise, but with a smaller proportion of the population in the labor force to pay for these increasing social security and health care costs. The problem has been magnified by the departure of workers from the labor force at younger ages along with substantial increases in the number of years they spend in retirement. Thus the theme above: Some of the bounty of longer lives must be allocated to prolonging the labor force participation of older workers. It will not be feasible to use all of the increase in longevity to increase years in retirement, a theme also emphasized in Wise (2010). This is the need.

Although not discussed further in this paper, the theme is based on three working assumptions. First, the increase in the labor force participation of older people will increase production and gross domestic product (GDP). Second, the increase in production will increase tax revenues. Third, the increase in tax revenues will increase the funds available to pay for increasing social security and health care costs. In addition, the increase in labor force participation at older ages would likely increase personal saving. In the United States, with the conversion from defined benefits to a personal account system based largely on 401(k) plans, this increase would happen essentially by default. Increased personal saving would be drawn down over fewer retirement years and, thus, would increase resources in each year of retirement.

Many of the conclusions reported in this paper are based on results obtained in the International Social Security Project. Researchers who have participated in this project are listed in Box 5-1.

To emphasize the theme of population aging in Asia, wherever possible I have compared labor force and mortality trends in the participating countries with trends in China. Japan, another Asian country, is a key participant of the International Social Security Project.

The paper is in three sections. The first section, which is the primary emphasis, considers the rationale for considering longer working lives in the face of the demographic trends. In particular, I emphasize healthier older populations. I note the reduction in mortality is a marker of better health, not because it is equivalent to reductions in morbidity or to other measures of health status, but because it is an indicator of health that is comparable across countries and comparable over time within the same country. I discuss the relationship between labor force participation and health and how it has changed over time. I then emphasize the relationship between mortality and self-assessed health and point to measures of the capacity to work, based on analysis by Cutler, Meara, and Richards-Shubik

BOX 5-1

International Social Security Project: List of Researchers

| Belgium | Alain Jousten, Mathieu Lefèbvre, Sergio Perelman, Pierre Pestieau Arnaud Dellis, Raphaël Desmet, Jean-Philippe Stijns |

| Canada | Michael Baker, Kevin Milligan Jonathan Gruber |

| Denmark | Paul Bingley, Nabanita Datta Gupta, Peder J. Pedersen |

| France | Luc Behaghel, Didier Blanchet, Thierry Debrand, Muriel Roger Melika Ben Salem, Antoine Bozio, Ronan Mahieu, Louis-Paul Pelé, Emmanuelle Walraet |

| Germany | Axel Börsch-Supan, Hendrik Juerges Simone Kohnz, Giovanni Mastrobuoni, Reinhold Schnabel |

| Italy | Agar Brugiavini, Franco Peracchi |

| Japan | Takashi Oshio, Satoshi Shimizutani Akiko Sato Oishi, Naohiro Yashiro |

| Netherlands | Adriaan Kalwij, Arie Kapteyn, Klaas de Vos |

| Spain | Pilar García Gómez, Sergi Jiménez-Martín, Judit Vall Castelló, Michele Boldrín, Franco Peracchi |

| Sweden | Lisa Jönsson, Mårten Palme, Ingemar Svensson |

| United Kingdom | James Banks, Richard Blundell, Antonio Bozio, Carl Emmerson Paul Johnson, Costas Meghir, Sarah Smith |

| United States | Kevin Milligan Courtney Coile, Peter Diamond, Jonathan Gruber |

| NOTE: The participants in the current phase are listed first; others who have participated in one or more of the previous phases are listed second and shown in italics. | |

(2011). My concentration on the rationale is motivated by the belief that discussion of longer working lives must be predicated by discussion of why working longer is a plausible adjustment to the changing age structure of the population.

In the second section, I review evidence on how to facilitate working

lives, drawing in large part from the International Social Security Project and discussing the false rationale for inducing older workers to leave the labor force. In many countries, the proposition that older workers must leave the labor force to provide jobs for young workers is used as a reason to induce older workers to leave the labor force. Based on results from the International Social Security Project, however, no evidence supports this “boxed economy” view of the labor market. The final section of the paper presents a summary and conclusions.

THE RATIONALE

For ease of exposition, much of this section is based on comparative data for the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and China. I begin by considering mortality trends and by documenting long-run trends in mortality. Next, I compare the change in mortality trends to labor force participation. I then discuss the relationship between mortality and self-assessed health (SAH), a common measure of health status, and discuss evidence on the capacity to work at older ages.

Declining Mortality and Equivalent Mortality Ages

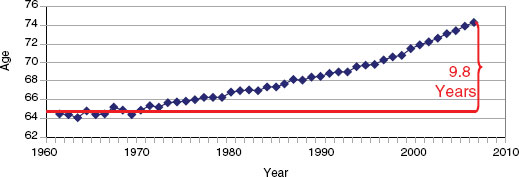

There are several ways to present mortality data that highlight more clearly the implications of mortality declines for health. One way is to ask how old one would have to be today to have the same mortality as a person of a given age in an earlier year. For example, consider the mortality rate of people aged 65 in the 1960s, and then consider the age at which the same mortality rate occurred in later years. Figure 5-1 shows the ages of equivalent mortality in the United Kingdom. Men aged 74 in 2007 had about the same mortality rate as men aged 65 in the 1960s. The

FIGURE 5-1 Age at which the mortality rate is the same as the mortality rate of a 65-year-old in the 1960s—by year, men in the United Kingdom.

SOURCE: Milligan and Wise (2011).

TABLE 5-1 Gain in Equivalent Mortality Age, Early 1980s to 2005, for Men Aged 65 in Initial Year

| Mortality Rate in | Equivalent Mortality | Gain in | ||

| Country | First Year | First Year (%) | Age in 2005 | Years |

| Belgium | 1960 | 3.53 | 72.3 | 7.8 |

| Canada | 1961 | 3.26 | 73.4 | 8.4 |

| Denmark | 1961 | 2.69 | 70.0 | 5.0 |

| France | 1960 | 3.22 | 73.5 | 8.5 |

| Germany | 1960 | 4.15 | 73.2 | 8.2 |

| Italy | 1960 | 3.06 | 72.8 | 7.8 |

| Japan | 1960 | 3.56 | 75.0 | 10.0 |

| Netherlands | 1960 | 2.35 | 69.7 | 4.7 |

| Spain | 1960 | 3.54 | 71.9 | 6.9 |

| Sweden | 1960 | 2.37 | 71.4 | 6.4 |

| UK | 1960 | 3.53 | 73.4 | 8.4 |

| US | 1960 | 3.84 | 74.1 | 9.1 |

SOURCE: Milligan and Wise (2011).

difference is about 9.8 years. Thus, by this measure, there has been a very large improvement in health (a reduction in the mortality rate) over the past several decades.

The same comparison has been made for each of the countries participating in the International Social Security Project. Table 5-1 shows the age in 2005 with the same mortality as men aged 65 in the early 1960s for each of the countries. Although in each country the equivalent mortality age in 2005 was substantially greater than age 65-mortality in the early 1960s, there is also substantial variation in the 2005 equivalent age—from a low of age 69.7 (an increase of 4.7 years) in the Netherlands to a high of age 75 (an increase of 10 years) in Japan, the only Asian country participating in the International Social Security Project. Below, I compare equivalent mortality ages to equivalent self-assessed health ages, which may be closer to healthy equivalent ages.

Employment by Age

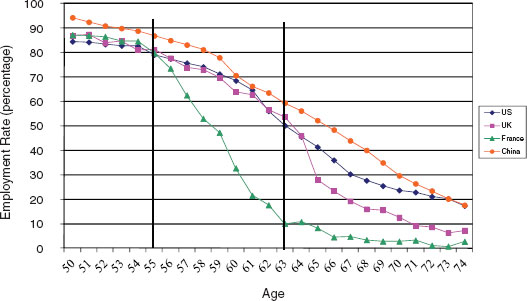

I next present a series of figures to describe the change over time in the relationship between employment and mortality and the relationship between employment and age. I begin with employment by age now and then turn to employment by mortality and how it has changed over time. Figure 5-2 shows employment by age in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and China. While the employment rate was similar for these countries through age 50, by age 63 the employment rate in France was much lower than in the other countries. The provisions of the pen-

FIGURE 5-2 Employment by age, United States, United Kingdom, and France, 2007, and China, 2005.

SOURCES: Milligan and Wise (2011) and data from China Census (2005).

sion plan in France provide very substantial incentives to leave the labor force early.

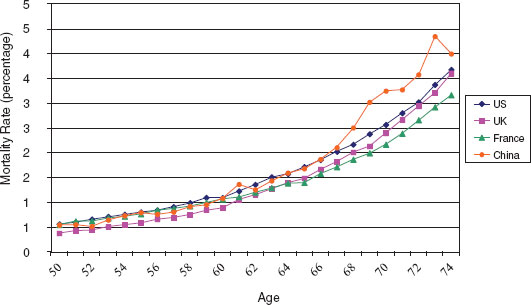

Mortality by Age

I now turn to employment by mortality and begin by describing mortality by age across the countries. Figure 5-3 shows mortality by age in the same four countries. While there are differences across countries, the variation appears small relative to differences in employment by age.

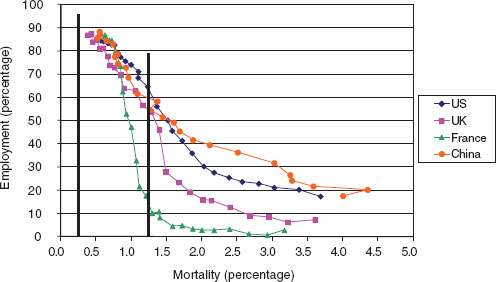

Employment by Mortality

We want to understand how employment varies across countries, given health. Again, I use mortality as the measure of health, sticking with a measure that is comparable across countries. I then compare the employment rate across countries for given levels of mortality. Figure 5-4 shows employment by mortality for each of the four countries. Taking the ages at which the mortality rate in each of these countries was about 0.5 percent indicates that the employment rates are very similar, ranging from about 0.82 to 0.90. But as the mortality rate increases, the divergence across the countries increases. For example, at the age at which the mortality rate in each of the countries was 2.0%, the employment rates varied

FIGURE 5-3 Mortality by age, United States, United Kingdom, and France, 2007, and China, 2005.

SOURCES: Milligan and Wise (2011) and data from National Bureau of Statistics of China (2006).

FIGURE 5-4 Employment and mortality by age, United States, United Kingdom, and France, 2007, and China, 2005.

SOURCES: Milligan and Wise (2011); data from National Bureau of Statistics of China (2006) and China Census (2005).

from about 3% in France, to 16% in the United Kingdom, to 30% in the United States, and about 40% in China. Like the increasing divergence in employment rates by age, the divergence in employment as people age and mortality increases reflects the large variation in the provisions of pathways to retirement.

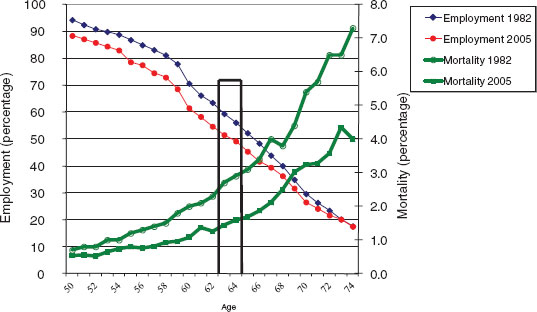

To understand the cross-country comparisons in Figures 5-3 and 5-4, it helps to consider in more detail the relationship between employment and mortality. Figure 5-5a shows the relationship between age and employment in 1982 and 2005 in China. As highlighted, the employment rate at ages 62 and 63 declined by about 9% over this 23-year period. Also at these ages the mortality rates declined substantially between 1982 and 2005—about 1.3% at each age. Figure 5-5b presents a different view of the data, showing the employment rate by mortality in 1982 and 2005. Consider first the age at which 50% of men were employed. In 2005, the mortality rate when 50% of men were employed was 3.2%; 23 years later, in 2005, the mortality rate was only 1.6%, a decline of 1.6%. That is, for the employment rate to be 50% in 2005, men “had to be” much healthier (by the mortality measure) than they were in 1982. Looking at the data another way, at the age at which the mortality rate was 1.5%, in 1982 about 80% of men were employed, but in 2005, only 50% were employed.

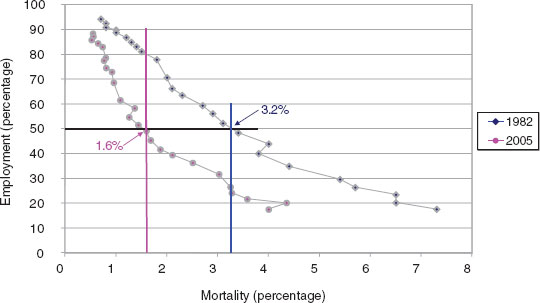

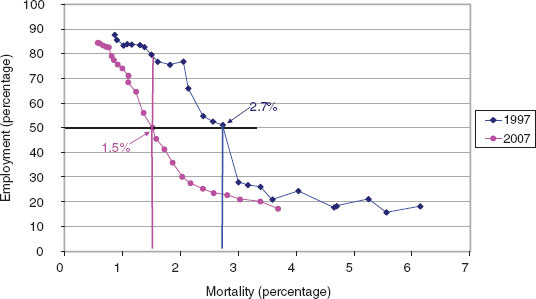

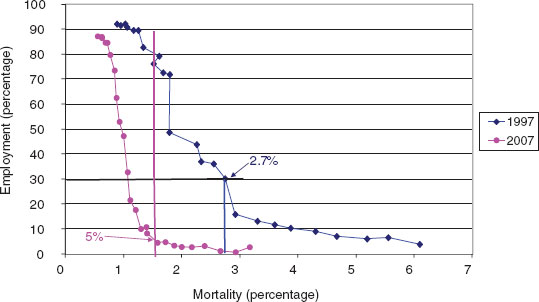

The version of the data presented in Figure 5-5b for China is presented for the United States and for France in Figures 5-6 and 5-7, respectively.

FIGURE 5-5a Employment and mortality by age, men in China, 1982 and 2005.

SOURCES: Data from National Bureau of Statistics of China (2006) and China Census (1982, 2005).

FIGURE 5-5b Employment by mortality in China, 1982 and 2005.

SOURCES: Data from National Bureau of Statistics of China (2006) and China Census (1982, 2005).

FIGURE 5-6 Employment by mortality, men in the United States, 1977 and 2007.

SOURCE: Milligan and Wise (2011).

For these countries, the data are for 1977 and 2007, instead of 1982 and 2005. For the United States, Figure 5-6 shows that in 2007, the mortality rate when 50% of men were employed was 2.7%; 30 years later in 2007, the mortality rate was only 1.5%, a decline of 1.2%. That is, for the employ-

FIGURE 5-7 Employment by mortality, men in France, 1977 and 2007.

SOURCE: Milligan and Wise (2011).

ment rate to be 50% in 2007, men “had to be” much healthier (by the mortality measure) than they were in 1977. Looking at the data another way, at the age at which the mortality rate was 1.5%, in 1977 about 80% percent of men were employed, while in 2007, the rate dropped to only 50%.

In France, the employment rate at ages 62 and 63 declined by almost 30%. In addition, the mortality rate at these ages declined by about 1%, about the same as in the United States and somewhat less than in China. Figure 5-7 shows that in France, at the age at which 30% percent of men were employed, the mortality rate was 2.7% in 1977 but only 1.1% in 2007, a decline of 1.6%. That is, for the employment rate to be 30% in 2007, men “had to be” much healthier (by the mortality measure) than they were in 1977. Further, looking at the data another way, at the age at which the mortality rate was 1.5%, almost 80% of men were employed in 1977 compared to only 5% in 2007.

Mortality Versus Self-Assessed Health

The figures above highlight the changing relationship between mortality and employment. As emphasized, mortality lends itself to these comparisons because this measure is comparable across countries and across time within countries. Other potential measures of health status are not comparable across countries and may not be comparable across time within countries. Nonetheless, I explore the relationship between

mortality and SAH status, perhaps the most commonly used summary measure of health status. I compare these two measures in several ways. First, I compare SAH and future mortality in the United States. Second, I compare mortality-equivalent ages over time with SAH-equivalent ages over time using data for two countries, the United States and Sweden, as illustration. Third, I consider within countries the time-trend relationship between mortality and SAH. Finally, I combine the latter comparisons to estimate the cross-country relationship between the change in mortality over time with the comparable change in SAH over the same period.

SAH and Future Mortality in the United States

Table 5-2 shows that in the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS), SAH in 1992 was strongly predictive of subsequent mortality. The table shows the proportion of men and women deceased by 1996, 2002, and 2008. For example, for men in excellent health, only 11.4% were deceased by 2008, compared to 57.9% for men in poor health. More generally, although mortality is not equivalent to health status or disability, it is likely to be an important indicator of age-equivalent work potential over time. Heiss et al. (2009) used HRS data to show a striking relationship at all ages between self-reported health status and death rates and between self-reported disability status and death rates.2

Mortality-Equivalent Ages Versus SAH-Equivalent Ages

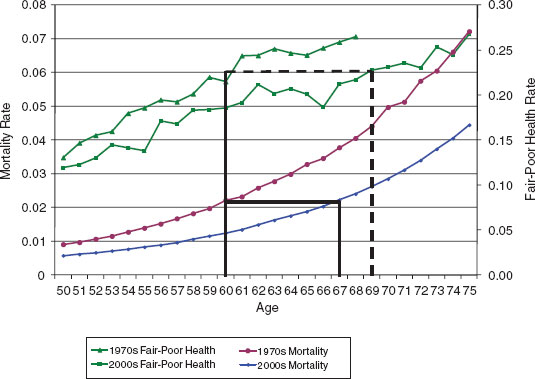

Figure 5-8 compares these two measures for the United States. First, the figure shows mortality by age in 1977 and 2007. The figure shows that a person aged 77 in 2007 had about the same mortality rate as a person aged 60 in 1977, a difference of about 7 years. Second, the figure shows the proportion of people who reported they were in fair or poor health, by age, in the 1970s and in the 2000s, based on the National Health Interview Survey. Comparing these two trends, men who were aged 69 in the 2000s had about the same SAH as men who were more than 9 years younger, aged 60, in the 1970s. Thus in this example, there was a greater difference

____________

2 There is substantial additional evidence of declining disability in the United States among people older than 65. Using data from the National Long-Term Care Survey, Manton, Gu, and Lamb (2006) showed that in each of three age intervals—65-74, 75-84, and 85 and older—there has been a large decline since 1982 in the percentage of older people who need help with activities of daily living. But Martin et al. (2007, 2009), examining self-assessed trends in fair/poor health, questioned whether such declines pertain to the younger old in more recent years. Weir (2007) also questioned the decline in health status among the younger old, drawing particular attention to the increase in obesity.

TABLE 5-2 Percentage of HRS Respondents, Aged 51-61 in 1992 Who Are Deceased by the Beginning of Each Wave, by Self-Assessed Health (SAH) Status in 1992, United States

| Self-Reported Health in 1992 | |||||||||

| Year | Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor | ||||

| Men | |||||||||

| 1996 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 4.3 | 10.8 | ||||

| 2002 | 5.8 | 7.2 | 13.3 | 22.1 | 36.9 | ||||

| 2008 | 11.4 | 15.6 | 25.8 | 36.5 | 57.9 | ||||

| % in Category | 24.5 | 29.6 | 27.8 | 11.5 | 6.6 | ||||

| Women | |||||||||

| 1996 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 4.2 | ||||

| 2002 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 7.1 | 15.2 | 24.4 | ||||

| 2008 | 6.4 | 10.3 | 15.2 | 28.8 | 36.8 | ||||

| % in Category | 23.1 | 30.7 | 25.7 | 13.6 | 6.9 | ||||

SOURCE: Milligan and Wise (2011).

FIGURE 5-8 Mortality and self-assessed health (SAH) status, 1970s and 2000s, United States.

SOURCE: Milligan and Wise (2011).

in age-equivalent SAH than in age-equivalent mortality (about 9 versus 7 years).

Mortality-equivalent ages versus SAH-equivalent ages for Sweden are compared in Milligan and Wise (2011). Based on rough approximations, a person aged 63 in 2005 in Sweden had about the same mortality rate as a person aged 55 in 1976, a difference of about 8 years. Men who were about 64 in 2005 had about the same SAH as men who were about 9 years younger, age 55, in 1976. In this example, Sweden also shows a greater difference in age-equivalent SAH than in age-equivalent mortality (about 9 versus 8 years).

Thus, in both the United States and Sweden, there appears to be a substantial correspondence between age-equivalent mortality and age-equivalent SAH. These results must be interpreted with caution, however. Similar comparisons for the United Kingdom do not reveal the same pattern. While the difference in mortality rates between the 1970s and early 2000s are similar to the United States, differences in SAH do not follow the pattern suggested by the U.S. and Swedish data.

Cross-Country Comparison Between the Percentage Change in Mortality and the Percentage Change in SAH

Milligan and Wise (2011) find a strong relationship across countries in the percentage decline in mortality within a country and the percentage decline in SAH. For the nine countries in the International Social Security Project with data on the proportion in fair or poor health (or 1 minus the proportion in better health), there is a close relationship between the change in mortality and the change in SAH. A regression of the percentage change in fair or poor SAH on the percentage change in mortality in the nine countries yields an estimated slope coefficient of close to one (0.97). This suggests a fairly tight within-country relationship between improvements in mortality and improvements in self-assessed health, providing a link between the mortality analysis above and one commonly used health measure. The data also show, however, that the level of SAH varies greatly from country to country, consistent with substantial country-specific SAH response effects.

Potential for Work in the United States

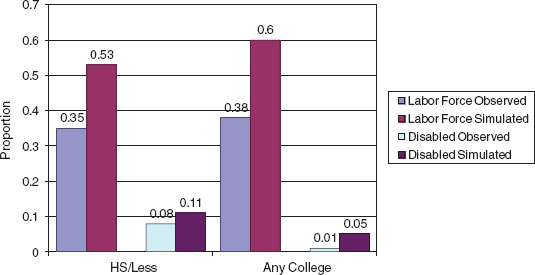

An alternative approach to comparing health status and employment is to estimate the potential for work at older ages. Cutler, Meara, and Richards-Shubik (2011) followed this approach. They first estimate the relationship between labor force participation on the one hand and demographic and health characteristics on the other for people aged 62-64. Then

FIGURE 5-9 Labor force status in the United States, with and without Social Security and Medicare benefits, aged 65-69, men.

SOURCE: Cutler, Meara, and Richards-Shubik (2011).

they use these estimates to simulate the labor force participation for older people aged 65-69, which they call capacity for work. These simulated participation rates do not account for Medicare or Social Security provisions. Results for men with a high school degree or less and for men with any college are shown in Figure 5-9. The actual “observed” labor force participation—that is, affected by Medicare eligibility and Social Security provisions—is compared with the simulated participation that does not account for Medicare or for Social Security provisions. For both education groups, the simulated labor force participation is substantially higher than the observed rate—53 versus 35% for the high school or less group and 60 versus 38% for the any-college group. The simulated proportion on disability is also higher than the observed proportion, but the difference is very small relative to the difference in labor force participation.

THE HOW

I highlight three policy changes that can be used to facilitate longer working lives and discuss each briefly.

Social Security Provisions That Induce Early Retirement

The first policy is to eliminate Social Security provisions that induce early retirement and penalize work at older ages—implicit tax on work. Consider the compensation for working another year, say from

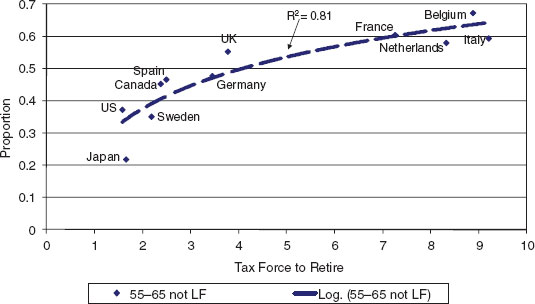

age 60 to 61. Compensation is in two forms: the wage earnings for working another year and the increase in future retirement benefits. One might suppose that the increase in future retirement benefits would be at least large enough to offset the receipt of benefits for one fewer year. But in many countries, the present value of future social security benefits is reduced if the person works another year. That is, some of the gain in earnings from working another year is offset by the loss in future social security benefits. Following Gruber and Wise (1999), I call this the implicit tax on work or the tax force to retire.

Figure 5-10, taken from Gruber and Wise (1999), shows the strong relationship between the tax force to retire and the proportion of men aged 55-65 out of the labor force. The horizontal axis shows the sum of the tax force to retire from the early retirement age in a country to age 69. The vertical axis shows the proportion of men out of the labor force. In the countries with the lowest implicit tax rates, fewer than 40% of men in the 55-65 age range are out of the labor force, while in countries with the highest implicit tax rates, as many as 67% are out of the labor force. In making calculations like these, it is important to include disability insurance programs, special unemployment programs, and other programs that in many countries serve as early routes to retirement. These issues are discussed in detail in Gruber and Wise (1999).

FIGURE 5-10 Proportion of men, aged 55-65, out of the labor force, by tax force to retire.

SOURCE: Gruber and Wise (1999).

The Boxed Economy View of the Labor Market

The second “policy” to facilitate longer working lives is to abandon the false assumption that economies are “boxed.” This proposition holds that older people must retire to provide jobs for the young. It is often used as an excuse or as a rationale for provisions that induce older people to retire. As one example from many countries, Pierre Mauroy, then-Prime Minister of France, said this in 1981:

And I would like to speak to the elders, to those who have spent their lifetime working in this region, and well, I would like them to show the way, that life must change; when it is time to retire, leave the labor force in order to provide jobs for your sons and daughters. That is what I ask you. The Government makes it possible for you to retire at age 55. Then retire, with one’s head held high, proud of your worker’s life. This is what we are going to ask you.… This is the contrat de solidarité [an early retirement scheme available to the 55+ who quit their job]. That those who are the oldest, those who have worked, leave the labor force, release jobs so that everyone can have a job (quoted in Gaullier (1982), L’avenir à reculons, page 230).

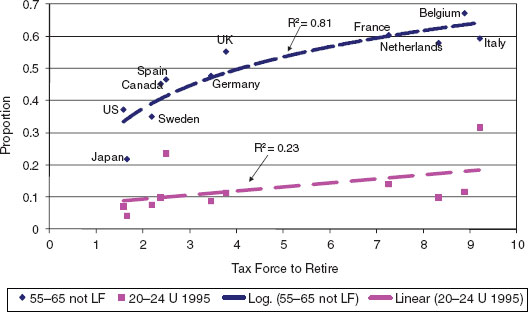

Gruber and Wise (2010) consider a series of methods to estimate the relationship between the employment of older people and the employment of youth, based on the analyses of the authors in the countries participating in the International Social Security Project. I show an example of the evidence, adding to Figure 5-10 above. The strong relationship between the tax force to retire and the proportion of older men out of the labor force is apparent in Figure 5-10. If the incentives that reduced the proportion of older people in the labor force (and increased the proportion out of the labor force) created more job opportunities for young people, then the tax force to retire should be related to youth employment. The greater the tax force to retire, the lower youth unemployment should be and the greater youth employment should be. Figure 5-11 is the same as Figure 5-10 but with the addition of the unemployment rate of youth aged 20 to 24. Essentially there is no relationship across countries between the tax force for older people to retire and the unemployment of youth. Indeed, the actual relationship is slightly positive—the greater the tax force to retire, the greater is youth unemployment. Similarly, the relationship between the tax force to retire and youth employment (not shown) is negative: the greater the tax force to retire, the lower the employment rate of youth.

Gruber and Wise show estimates based on several additional methods of analysis. One method is within-country “natural experiment” comparisons that help to demonstrate the relationship between within-country

FIGURE 5-11 Men, aged 55-65, out of the labor force and youth, aged 20-24, unemployed (1995), by tax force to retire.

SOURCE: Gruber, Milligan, and Wise. (2009).

reforms and the consequent changes in the employment of the old on the one hand and changes in the employment of the young on the other hand. A second method is based on various cross-country comparisons, and a third method presents a more formal estimation based on panel regression analysis.

As it turns out, all of the various estimation methods yield very consistent results. In particular, there is no evidence that reducing the employment of older persons provides more job opportunities for younger persons, nor is there evidence that increasing the labor force participation of older persons reduces the job opportunities of younger persons.

Private Pension Provisions and Flexible Work Arrangements

The third policy to facilitate work at older ages is to remove private plan incentives to retire early and to provide flexible work arrangements for older workers. The evidence on pension plan provisions summarized above pertains to public pension systems, but these are not the only systems that contain incentives to leave the labor force early. Defined benefit systems in the private sector in the United States typically contain provisions that strongly encourage early retirement (Stock and Wise, 1990a,b). Defined benefit plans in the private sector are becoming less prevalent

and are being replaced in large part by 401(k)-like plans that have none of the incentive effects of defined benefit plans. However, defined benefit plans are still common in state and local governments and in the federal government. These plans are typically very generous and typically have strong incentives to retire early. And while Social Security incentives to retire early based on non-actuarial benefit adjustments have been largely eliminated, Goda, Shoven, and Slavov (2007a,b) show that other provisions still discourage work at older ages. In addition, there are other adaptations that might encourage longer working lives. For example, institutional arrangements within firms to provide for partial retirement could well prolong work on a part-time basis.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

I have briefly described the need for longer working lives in response to demographic trends that will greatly increase the proportion of the population that is older. The increase in the older population will increase social security and health care costs, while prolonging working lives can be an important way to pay for these rapidly increasing costs. I have emphasized that some of the bounty of longer lives must be allocated to prolonging the labor force participation of older workers.

To rationalize the plausibility of increasing working lives to adjust to demographic trends, it is important to understand the changes in health over the past four or five decades. Thus I have given primary attention to the increasing health status of older people, and I have discussed the relationship between change in health status over time and change in labor force participation. The evidence shows that the labor force participation at a given health status is much lower today than it was three or four decades ago. Much of my discussion is based on the decline in mortality rates, not because mortality is equivalent to morbidity or other measures of health, but because it is a measure comparable across countries and comparable over time within the same country. I also considered the relationship between mortality and self-reported health, also a common measure of health status, and I have considered evidence on the capacity for work at older ages.

A striking feature of the data is the correspondence between employment and mortality trends in China and the United States, as well as European countries such as the United Kingdom. Through age 65, employment of men by age is only slightly higher in China than in the United States and France, and also through age 65, mortality by age is similar in China and in European countries. But for mortality rates above 1.5%, employment for men in China is substantially greater than employment in the United States and much greater than employment in the United Kingdom

and the United States, presumably due to the provisions of social security programs in the United States and in European countries.

I have also summarized how longer working lives might be facilitated. I have emphasized three policy directions: removing public social security provisions that induce older people to leave the labor force; abandoning the boxed economy view of the labor market that is often used as an excuse, or rationale, for providing incentives for older people to leave the labor force; and removing private pension plan provisions that induce early retirement and developing flexible work arrangement for older workers.

These results, based on developed countries including Japan, may have substantial implications for China. China has a very rapidly increasing older population. Yet China also has mandatory retirement ages for many workers—as young as age 50 for women and age 55 for men. Thus at a time when the cost of support for older workers is increasing, older workers are driven from the labor force (or their exit from the labor force is facilitated) by mandatory retirement ages. The data, however, suggest that many who “retire” at mandatory retirement ages remain in the labor force, perhaps in other jobs.

Finally, even in light of these trends, there are limits on work at older ages. In all countries, people with greater self-assessed disability or low health status are more likely to retire early. Policies that reduce the incentives to retire early may also limit the retirement options of people in poor health. Thus, any comprehensive analysis of the potential for longer working lives must also consider the limits on work at older ages.

REFERENCES

China Census. (1982). National Bureau of Statistics of China, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

China Census. (2005). National Bureau of Statistics of China, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Cutler, D., E. Meara, and S. Richards-Shubik. (2011). Healthy Life Expectancy: Estimates and Implications for Retirement Age Policy. Available: http://www.nber.org/programs/ag/rrc/NB10-11%20Cutler,%20Meara,%20Richards%20Final,%20REVISED.pdf.

Gaullier, X. (1982). L’avenir à Recoulons: Chomage et Retraite. Paris: Éditions Economie et Humanisme.

Goda, G.S., J.B. Shoven, and S.N. Slavov. (2007a.) Removing the Disincentives in Social Security for Long Careers. NBER Working Paper No. 13110. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Goda, G.S., J.B. Shoven, and S.N. Slavov. (2007b). A Tax on Work for the Elderly: Medicare as a Secondary Payer. NBER Working Paper No. 13383. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gruber, J., and D.A. Wise (Eds.). (1999). Social Security and Retirement Around the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gruber, J., and D.A. Wise (Eds.). (2010). Social Security Programs and Retirement Around the World: The Relationship to Youth Employment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gruber, J., K. Milligan, and D.A. Wise. (2009). Social Security Programs and Retirement Around the World: The Relationship to Youth Employment—Introduction and Summary. NBER Working Paper No. 14647. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Heiss, F., A. Börsch-Supan, M. Hurd, and D. Wise. (2009). Pathways to disability: Predicting health trajectories. Pp. 105-150 in Health at Older Ages: The Causes and Consequences of Declining Disability Among the Elderly, D. Cutler and D.A. Wise (Eds.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Manton, K., X. Gu, and V. Lamb. (2006). Change in chronic disability from 1982 to 2004/2005 as measured by long-term changes in function and health in the U.S. elderly population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(48):18374-18379.

Martin, L., V. Freedman, R. Schoeni, and P. Andreski. (2007). Feeling better? Trends in general health status. Journal of Gerontology: Series B 62:S11-S21.

Martin, L., V. Freedman, R. Schoeni, and P. Andreski. (2009). Health and functioning among baby boomers approaching 60. Journal of Gerontology: Series B 64:369-377.

Milligan, K., and D.A. Wise. (2011). Social Security Programs and Retirement Around the World: Historical Trends in Mortality and Health, Employment, Disability Insurance Participation and Reforms-Introduction and Summary. NBER Working Paper No. 16719. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (1987). China Statistical Yearbook 1987. Beijing: China Statistics Press. Available: http://tongji.cnki.net/overseas/engnavi/HomePage.aspx?id=N2010100096&name=YINFN&floor=1.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2006). China Statistical Yearbook 2006. Beijing: China Statistics Press. Available: http://tongji.cnki.net/overseas/engnavi/HomePage.aspx?id=N2010100096&name=YINFN&floor=1.

Shoven, J.B. (Forthcoming). New age thinking: Alternative ways of measuring age, their relationship to labor force participation, government policies and GDP. Pp. 17-36 in Research Findings in the Economics of Aging, D.A. Wise (Ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stock, J.H., and D.A. Wise. (1990a). Pensions, the option value of work, and retirement. Econometrica 58:1,151-1,180.

Stock, J.H., and D.A. Wise. (1990b). The pension inducement to retire: An option value analysis. Pp. 205-230 in Issues in the Economics of Aging, D.A. Wise (Ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weir, D. (2007). Are baby boomers living well longer? Pp. 95-112 in Redefining Retirement: How Will Boomers Fare?, B. Madrian, O.S. Mitchell, and B.J. Soldo (Eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wise, D. (2010). Facilitating longer working lives: International evidence on why and how. Demography 47:S131-S149.