History, Diagnostic Criteria, and Epidemiology

This chapter provides an overview of the epidemiology of posttrau-matic stress disorder (PTSD). It begins with a brief history of the disorder in the American military, which is followed by a discussion of its diagnostic criteria. The remainder of the chapter presents factors associated with trauma and PTSD, first in the general population and then in military and veteran populations, with an emphasis on combat as the traumatic event that triggered the development of PTSD. Although other traumatic events—such as the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and Hurricane Katrina—have increased knowledge about PTSD, this chapter does not focus on civilian populations or nonmilitary related trauma. The chapter concludes with special epidemiologic considerations regarding PTSD in military populations and their implications for screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

Prior to the codifying of PTSD by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) as a distinct mental health disorder in 1980 (APA, 1980), characteristic symptoms of PTSD had been recognized and documented in the 19th century in civilians involved in catastrophic events, such as railway collisions, and in American soldiers fighting in the Civil War (Birmes et al., 2003; Jones, 2006; Welke, 2001). Many Civil War soldiers had diagnoses of nostalgia or melancholia, characterized by lethargy, withdrawal, and “excessive emotionality” (Birmes et al., 2003). Others had diagnoses of exhaustion, effort syndrome, or heart conditions variously called “irritable

heart,” “soldier’s heart,” and “cardiac muscular exhaustion.” Many medical professionals and surgeons at the time believed that those conditions arose from the heavy packs that soldiers carried, insufficient time for new recruits to acclimatize to the military lifestyle, homesickness, and, as one army surgeon stated, poorly motivated soldiers who had unrealistic expectations of war (Jones, 2006). For much of the 20th century, psychologic conditions and impairments in military personnel were not accorded high medical priority because of the high fatality rates from disease, infection, and accidental injuries during war.

During World War I, shell shock and disordered action of the heart were commonly diagnosed in combat veterans (Jones, 2006). Symptoms of shell shock included tremors, tics, fatigue, memory loss, difficulty in sleeping, nightmares, and poor concentration—similar to many of the symptoms associated with PTSD. What is now known as delayed-onset PTSD was termed old-sergeant syndrome during the era of the world wars, when after prolonged combat, experienced soldiers were no longer able to cope with the constant threats of death or serious injury (Shephard, 2000). Stemming from the World War I definition of shell shock, other common diagnoses of soldiers during World War II included exhaustion, battle exhaustion, flying syndrome, war neurosis, cardiac neurosis, and psychoneurosis (Jones, 2006).

It was not until after the Vietnam War that research and methodical documentation of what was then termed combat fatigue began to accelerate in response to the many veterans suffering from chronic psychologic problems that resulted in social and occupational dysfunction (IOM, 2008a). The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Survey (NVVRS) was one of the first large-scale studies to examine PTSD and other combat-related psychologic issues in a veteran population (Kulka, 1990). The NVVRS helped to illuminate PTSD as a signature wound of the Vietnam War and resulted in greater recognition of PTSD as a mental health disorder. The findings contributed to the formal recognition of PTSD as a distinct disorder by the APA and later refining of the characteristic symptoms and diagnostic criteria.

Since 1980, PTSD has been the focus of much epidemiologic and clinical research, which in turn has led to modifications in the defining diagnostic criteria for PTSD. The current diagnostic criteria, taken from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), can be found in Box 2-1 (APA, 2000). The Department of Defense (DoD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs

BOX 2-1

DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

A1. The person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others

A2. The person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror

B. Re-experiencing Symptoms (requires one or more of):

B1. Intrusive recollections

B2. Distressing nightmares

B3. Acting/feeling as though event were recurring (flashbacks)

B4. Psychological distress when exposed to traumatic reminders

B5. Physiological reactivity when exposed to traumatic reminders

C. Avoidant/Numbing Symptoms (requires three or more of):

C1. Avoidance of thoughts, feelings, or conversations associated with the stressor

C2. Avoidance of activities, places, or people associated with the stressor

C3. Inability to recall important aspects of traumatic event

C4. Diminished interest in significant activities

C5. Detachment from others

C6. Restricted range of affect

C7. Sense of foreshortened future

D. Hyperarousal Symptoms (requires two or more of):

D1. Sleep problems

D2. Irritability

D3. Concentration problems

D4. Hypervigilance

D5. Exaggerated startle response

E. Duration of the disturbance is at least 1 month

Acute—when the duration of symptoms is less than 3 months

Chronic—when symptoms last 3 months or longer

With Delayed Onset—at least 6 months have elapsed between the traumatic event and onset of symptoms

F. Requires significant distress or functional impairment

SOURCE: American Psychiatric Association (2000) with permission.

(VA) both use these criteria in diagnosing the condition in service members and veterans.

PTSD is unique among psychiatric disorders in that it is linked to a specific trigger: a traumatic event (Criterion A1). Traumatic events known to

trigger PTSD include combat, natural and accidental disasters (for example, tsunamis, earthquakes, and vehicle and airplane crashes), and victimization or abuse (for example, sexual assault, armed robbery, and torture) (Basile et al., 2004; Harrison and Kinner, 1998; Hoge et al., 2004; Neria et al., 2007; Punamaki et al., 2010). PTSD may be of acute, chronic, or delayed onset. In acute PTSD, symptoms develop immediately or soon after experiencing a traumatic event and persist longer than a month but less than 3 months. If symptom duration is longer than 3 months, a person has chronic PTSD.

In delayed-onset PTSD, a person does not express symptoms for months or even years after the traumatic event (APA, 2000). The condition is considered partial or subthreshold PTSD if a person does not meet the full diagnostic criteria—exposure to a traumatic event and at least six symptoms: at least one B criterion of re-experiencing, at least three C criteria of numbing or avoidance, and at least two D criteria of hyperarousal—or if symptoms are not in the correct distribution. Changes to the diagnostic criteria for PTSD proposed for the next version of the DSM are shown in Box 2-2.

BOX 2-2

Proposed Changes in Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD in DSM-5

Research on PTSD and acute stress reactions has progressed, and diagnostic criteria are expected to change to reflect the updated version of DSM-5. One of the changes affects Criterion A1: it is proposed to expand it from experiencing or witnessing threatened or actual death or serious injury to oneself or others to include learning about such an event that happened to a relative or close friend and to include first responders or others who are continuously exposed to or experience details of traumatic events (Friedman et al., 2010). Because of the characteristics of the statistical association and predictive value of experiencing intense fear, helplessness, or horror during the event and onset of PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000a) and because some persons—for example, military personnel, who are trained to not have an emotional response during such an event—it has been proposed that Criterion A2 be eliminated (Friedman et al., 2010).

Other proposed changes for PTSD in DSM-5 include replacing the current three-pronged model with a four-pronged model. In the proposed model, Criterion B would become “Intrusion Symptoms,” Criterion C “Persistent Avoidance,” Criterion D “Alterations in Cognition and Mood,” and Criterion E “Hyperarousal and Reactivity Symptoms.” Although all 17 symptoms of DSM-IV would be kept in the proposed DSM-5, some of them would be revised or regrouped (such as including anger and aggressive behavior with irritability), and three symptoms would be added: erroneous self-blame or other blame regarding the cause or consequences of trauma, pervasive negative emotional states, and reckless and self-destructive behavior. The final proposed change in DSM-5 is to omit the distinction between acute and chronic PTSD. There is no proposal to include cases of subthreshold, or subsyndromal, PTSD as a distinct disorder in DSM-5 (Friedman et al., 2010).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF PTSD IN THE GENERAL POPULATION

This section begins with a brief discussion of factors associated with the experience of trauma in the general population, inasmuch as this is a main criterion in the diagnosis of PTSD, before considering the epidemiology of PTSD in the general population. The next major section deals with trauma and epidemiology specific to military and veteran populations.

Men are more likely than women to experience potential traumatic events overall, although the types of traumatic events differ by sex (Tolin and Foa, 2006). Studies assessing the role of race and ethnicity have had mixed results but have found that whites have higher risks of exposure to any traumatic event than Hispanics and blacks (Noris, 1992; Roberts et al., 2011). Other factors found to be associated with increased risk of experiencing traumatic events include lower education attainment (less than a 4-year college degree), lower annual income (less than $25,000), and nonheterosexual orientation (Breslau et al., 1998; Roberts et al., 2010). Three prospective studies have documented that externalizing behavioral problems (for example, difficult temperament and antisocial behavior) in early childhood increase the risk of traumatic-event exposure—particularly assaultive violence—over a lifetime (Breslau et al., 2006; Koenen et al., 2007; Storr et al., 2007).

Trauma type and severity are central determinants of the risk of development of PTSD. Experiencing physical injuries (penetrating and assault), viewing the event as a true threat to one’s life, and suffering major losses are all associated with a higher risk of PTSD (Holbrook et al., 2001; Ozer et al., 2003). The occurrence of dissociation itself during a traumatic event does not appear to predict development of PTSD as much as dissociation that persists after the event (Panasetis and Bryant, 2003) or the experience of perievent emotional reactions (Galea et al., 2003). As recognized by the VA / DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress (2010), lack of social support, trauma severity, and ongoing life stress increase the risk of PTSD. Lack or loss of social support (for example, spouse, friends, or family) after a traumatic event and ongoing life stress—including loss of employment, financial strain, and disability—have been associated with increased risk of PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000a; Ozer et al., 2003).

Several large, nationally representative surveys have provided estimates of the prevalence of PTSD in the general population. The National Comor-bidity Survey (NCS), conducted from 1990 to 1992, was one of the first large-scale surveys to examine the distribution of and factors associated with psychiatric disorders in the United States. Using a structured diagnostic interview, the NCS found that the lifetime prevalence of PTSD was 7.8% overall (Kessler et al., 1995). In the National Comorbidity Survey– Replication (NCS–R) conducted 10 years after the original, the prevalence

of lifetime PTSD was estimated to be 6.8% overall and that of current (12-month) PTSD 3.6% overall (Kessler et al., 2005). The 2004–2005 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD to be 7.3% overall (Roberts et al., 2011).

Sex and trauma type are two risk factors associated with PTSD (protective factors are discussed in Chapter 5). PTSD prevalence has consistently been shown to differ by sex in the civilian population (Kessler et al., 1995, 2005; Tolin and Foa, 2006). The original NCS found PTSD prevalence to be twice as great in women as in men, and the NCS–R estimated it to be 2.7 times greater in women than in men (Harvard Medical School, 2007b; Kessler et al., 1995). The type of trauma experienced may lead to the discrepancy between the sexes. For example, Tolin and Foa (2006) found no sex differences associated with PTSD in persons who experienced assaultive violence or nonsexual child abuse or neglect, but there were marked differences between men and women who experienced combat, accidents, and disasters. Men were more likely to report having experienced a traumatic event over their lifetimes, but women were more likely to meet criteria for PTSD (Tolin and Foa, 2006), have PTSD symptoms four times as long as men (48 months vs. 12 months) (Breslau et al., 1998), have a poorer quality of life if they have PTSD (Holbrook et al., 2001; Seedat et al., 2005), and develop more comorbid psychiatric disorders (Seedat et al., 2005).

There is some evidence on the effect of race and ethnicity on the development of PTSD although findings are inconsistent among studies. Results from the 2004–2005 wave of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions showed that whites were more likely to have experienced any trauma, and lifetime prevalence of PTSD was highest in blacks and lowest in Asians. Even after adjustment for characteristics related to trauma, the risk of PTSD was significantly higher in blacks and lower in Asians than in whites in the sample (Roberts et al., 2011). Marshall et al. (2009) found that in a sample of survivors of physical trauma, Hispanic whites reported greater symptoms related to cognitive and sensory perception (for example, hypervigilance and emotional reactivity) and overall symptom severity than non-Hispanic whites. Other work has shown that Hispanic whites are more likely to report PTSD after a traumatic event than are non-Hispanic whites (Galea et al., 2004). In a study of adults 18–45 years old in the Detroit area, Breslau et al. (1998) found that nonwhites were not at higher risk for PTSD than whites.

PTSD can affect people of any age. In the NCS–R, people were divided into four cohorts: 18–29, 30–44, 45–59, and older than 59 years old. The highest lifetime and 12-month prevalences of PTSD were in the group 45–59 years old (9.2% and 5.3%, respectively), and the lowest prevalences (2.8% and 1.0%, respectively) were in the group over 59 years old (Harvard Medical School, 2007a, b). Results from the earlier NCS showed

a different distribution of lifetime prevalence of PTSD by age group. The lowest prevalence was in men 15–24 years old (2.8%) and women 45–54 years old (8.7%) (Kessler et al., 1995). However, most of those studies examined the association between current age of the participants and PTSD symptoms or diagnostic threshold, and the strength of association between age and development of PTSD is unknown. Prevalence estimates of PTSD by age groups may also be confounded by historical events, such as the Vietnam War.

Sexual orientation has been associated with risk of PTSD. The National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions found that the risk of PTSD was significantly higher in lesbians and gays, bisexuals, and heterosexuals with any same-sex partners than it was in the heterosexual reference group. After adjusting for demographic factors, the higher risk of PTSD was largely explained by nonheterosexuals’ greater exposure to violence, exposure to more potentially traumatic events, and earlier age at trauma exposure (Roberts et al., 2010).

Cognitive reserve—individual differences in brain structure and function that are thought to provide resilience against damage from neuropathology— is thought to be one important etiologic factor in the development and severity of PTSD and other neuropsychiatric disorders (Barnett et al., 2006). Intelligence quotient (IQ), a marker of cognitive reserve, has been shown to be inversely related to risk of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders (Batty et al., 2005; Walker et al., 2002). In a 17-year prospective study of randomly selected newborns in southeastern Michigan, Breslau et al. (2006) found that children who at the age of 6 years had an IQ of greater than 115 had a decreased conditional risk of PTSD after trauma exposure; however, the risk increased for children that experienced anxiety disorders and whom teachers rated as high for externalizing problems. Overall, the authors found that high IQ (115 or higher) protected exposed persons from developing PTSD in this cohort (Breslau et al., 2006).

Similarly, Koenen et al. (2007) examined the association between early childhood neurocognitive factors and risk of PTSD in a New Zealand birth cohort that was followed through the age of 32 years. The authors found that IQ assessed at the age of 5 years was inversely associated with risk for developing PTSD by the age of 32 years. No associations were found between PTSD and other neurodevelopmental factors assessed in the cohort, suggesting that the IQ–PTSD association was not a marker of broader neurodevelopmental deficits.

The findings on the strength of association between family psychiatric history and PTSD are mixed. In one analysis of NCS data, after controlling for previous traumatic events, parental mental health disorders were associated with increased risk of PTSD in both men and women (Bromet et al., 1998). Although Breslau et al. (1991) found statistically significant associations

between PTSD after a traumatic event and family psychiatric history of depression, anxiety, and psychosis, a meta-analysis of risk factors for PTSD did not find this association in either civilian or military population studies (Brewin et al., 2000b). A family history of psychiatric disorders may be indicative of adverse family environment, which may increase the risk of experiencing a traumatic event, such as abuse, during childhood (Breslau et al., 1995; Brewin et al., 2000b). A positive association was found between reported family history of psychopathologic conditions and higher rates of PTSD symptoms or diagnosis, but the strength of this relationship differed by the type of traumatic experience of the target event (stronger after noncombat interpersonal violence than after combat exposure) and method of PTSD assessment (stronger when symptoms were determined in interviews than in self-reports) (Ozer et al., 2003). In a study that followed a New Zealand birth cohort and assessed for PTSD at the age of 26 years and again at the age of 32 years, maternal depression before the age of 11 years was associated with increased risk of PTSD through the age of 32 years (Koenen et al., 2007).

Family and twin studies of PTSD have produced two major findings. First, PTSD has a genetic component. Modern genetic studies of PTSD began with the observation that relatives of probands (persons serving as index cases in genetic investigations of families) who had PTSD had a higher risk of the disorder than relatives of similarly trauma-exposed controls who did not develop PTSD. Twin studies established that genetic influences explain much of the vulnerability to PTSD, from about 30% in male Vietnam veterans (True et al., 1993) to 72% in young women (Sartor et al., 2011), even after genetic influences on trauma exposure are accounted for. Second, both family and twin studies suggest that there is strong overlap for genetic influences on PTSD and those of other mental disorders including major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and alcohol and drug dependence. For example, in a sample of Vietnam veterans, common genetic influences explained 63% of the major depression–PTSD comorbidity and 58% genetic variance in PTSD (Koenen et al., 2008a). Other studies using the Vietnam Era Twin Registry found genetic influences of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder symptoms (Chantarujikapong et al., 2001), alcohol dependence and drug dependence (Xian et al., 2000), and nicotine dependence (Koenen et al., 2005b) account for a substantial proportion of the genetic variance for PTSD. Those results suggest that most of the genes that affect the risk of PTSD also influence the risk of these psychiatric disorders and vice versa. A more complete discussion of genetic influences on PTSD is found in Chapter 3.

Several prospective studies have implicated pretrauma psychopathology in increasing the risk of PTSD. In a cohort of randomly selected newborns in southeastern Michigan followed for 17 years, children who at the age of

6 years were rated as having externalizing problems above the normal range were more likely to develop PTSD than children who were rated as normal externalizers; young adults who had received a diagnosis of any anxiety disorder at the age of 6 years were significantly more likely to develop PTSD than those who had not (Breslau et al., 2006). Another prospective study in a cohort of children of similar age entering first grade over a 2-year period and followed for 15 years, those who in first grade were categorized as highly anxious or having depressive mood were at higher risk for PTSD among those exposed to traumatic events than their peers who did not have these psychologic problems; exhibiting aggressive or disruptive behaviors, concentration problems, and low social interaction were not found to be associated with increased risk of PTSD in this cohort (Storr et al., 2007). A third prospective study, which followed a New Zealand birth cohort and assessed for trauma exposure and PTSD at the ages of 26 and 32 years, found several childhood risk factors to be associated with PTSD. Childhood temperament ratings were made at the ages of 3 and 5 years, and behavior ratings were made by teachers biannually from the ages of 5 through 11 years. Children who had difficult temperaments or antisocial behavior and who were unpopular were statistically more likely to develop PTSD than their peers who did not have these characteristics. Antisocial behavior assessed before the age of 11 years predicted development of PTSD at the age of 26 years and at the age of 32 years. Childhood poverty and high levels of internalizing symptoms in mothers were also associated with development of PTSD (Koenen et al., 2007).

Childhood abuse may have an effect on the development of PTSD. A meta-analysis that considered nine studies suggests that abuse during childhood is a risk factor for PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000b). Desai et al. (2002) found that physical or sexual childhood victimization or both increased the risk of adult victimization by an intimate partner. This aligns with NCS findings that women who experienced physical abuse during childhood had the highest risk of lifetime PTSD (Kessler et al., 1995).

In addition to pretrauma psychopathology or childhood abuse, prior trauma has been shown to increase the risk of PTSD. Ozer et al. (2003) found a significant association between a history of prior trauma and PTSD symptoms or diagnosis. Persons who experienced a traumatic event before the target stressor reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms on the average than persons who did not. Prior trauma was more strongly associated with PTSD in connection with traumatic experiences of noncombat interpersonal violence than with combat exposures (Ozer et al., 2003). However, more recent data from prospective studies offer evidence against the hypothesis that prior trauma alone increases the risk of PTSD. Using a random sample from a large health maintenance organization in southeastern Michigan, Breslau et al. (2008) found that prior experience of trauma does not necessarily

increase the risk of PTSD in response to a subsequent trauma. Only those persons who developed PTSD in response to a prior trauma had an increased risk of PTSD after a later trauma. A follow-up study on assaultive violence found that it was the development of prior PTSD after a trauma that was predictive of the development of current PTSD after a later trauma (Breslau and Peterson, 2010).

Trajectory of PTSD

The course of PTSD may remit with time, with steepest remission in the first 12 months after diagnosis. In a nonrandomized, observational, retrospective analysis based on the NCS, the median time until diagnostic criteria were no longer met in those who received treatment was 36 months compared with 64 months in those who did not receive treatment (Kessler et al., 1995). However, approximately one-third of PTSD cases do not remit even after many years of treatment. A prospective study of PTSD in rape victims found that half recovered spontaneously, with the steepest declines from the first to the fourth assessment (mean, 35 days after the assault), whereas victims who had a diagnosis of PTSD 2 months or more after the trauma (rape) were unlikely to recover without treatment (Rothbaum et al., 1992). Other studies have shown remission of PTSD after particular traumatic events, such as disasters, in the first 6 months after exposure to the event (Galea and Resnick, 2005). Although PTSD is triggered by the initial exposure to a traumatic event, several studies have shown that exposure to ongoing stressors and other traumatic events throughout life contributes to the persistence of PTSD in the general population (Galea et al., 2008).

Few studies have investigated the chronicity of PTSD, most conducted before some current therapies were available; therefore, they are relatively dated. Two similarly designed prospective observational studies of people who had diagnosed PTSD and who were seeking care in tertiary care psychiatric practices (Zlotnick et al., 1999) or primary care practices (Zlotnick et al., 2004) had similar findings. Over the 5-year follow-up of the 54 persons in the tertiary care study, the probability of experiencing full remission was 18%. Chronicity of PTSD was associated with a history of alcohol abuse or dependence and childhood trauma (Zlotnick et al., 1999). In the primary care study, the authors considered full and partial remission separately. The findings were similar to those of the tertiary care study: over the 2-year follow-up of the 84 primary care subjects, the probability of full remission was 18% and the probability of partial remission 69%. Both full remission and partial remission were associated with fewer co-morbid anxiety disorders and a smaller degree of psychosocial impairment. The authors also evaluated the type, dose, and duration of treatment. The treatment was not randomized, but there was no association between the

use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and PTSD status at any point during the follow-up period (Zlotnick et al., 2004).

Men who reported combat as their worst trauma in the NCS were more likely to have lifetime PTSD, delayed onset of PTSD symptoms, and unresolved PTSD symptoms than men who named other types of trauma as their worst (Prigerson et al., 2001). Veterans enrolled in the NVVRS who had ever had full or partial PTSD reported they had experienced symptoms 63% of the time during the preceding 5 years (data collected between 1994–1996); 55% reported having symptoms every month, and 17% reported having no symptoms. In the 3 months before assessment, 78% had been symptomatic (Schnurr et al., 2003).

PTSD is associated with several adverse outcomes, including lower quality of life, work-related impairment, and medical illness throughout its course (Marshall et al., 2001; Resnick and Rosenheck, 2008; Zatzick et al., 1997). Several studies have shown an adverse effect of PTSD on physical health (Weiss et al., 2011), and others have found that exposure to a traumatic event increases the risk of adverse physical health, including many of the leading causes of premature death, such as cardiovascular disease and stroke (Boscarino, 2008; Cohen et al., 2009, 2010; Dirkzwager et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2004; Kubzansky et al., 2007, 2009). The associations are thought to be mediated in part by health behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol use, and physical inactivity (Breslau et al., 2003; Dobie et al., 2004). Because it would be unethical to expose humans to major trauma experimentally, randomized studies of the trajectory of PTSD are not feasible. The only available studies of trajectory of PTSD are natural history and observational studies, so the inference of findings to the general populaton is limited, and this makes it difficult to project future care and treatment needs.

Comorbidities of PTSD

People who have PTSD often have co-occurring psychologic disorders, such as depressive disorders, substance dependence, panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, bipolar disorder, and somatization (APA, 2000). People who have diagnoses of more than one mental health disorder have greater impairment than those who have a single diagnosis (IOM, 2008b). Those additional disorders can precede or present simultaneously with PTSD, and they may also resolve before, after, or simultaneously with PTSD. A prospective study that used data from a New Zealand birth cohort found that 96.3% of all adults who at the age of 32 years had a diagnosis of PTSD in the preceding year and 93.5% of those meeting criteria for lifetime diagnosis of PTSD at the age of 26 years

had met criteria for diagnosis of another mental health disorder (major depression, an anxiety disorder, conduct disorder, marijuana dependence, or alcohol dependence) between the ages of 11 and 21 years (Koenen et al., 2008b).

An analysis of 23 studies found small but significant effect sizes of a relationship between PTSD and prior adjustment problems, including mental health treatment; pretrauma emotional problems, anxiety, or affective disorders; and, in particular, depression (Ozer et al., 2003). The strength of the relationship between prior adjustment problems and PTSD symptoms or diagnosis changed as a function of type of traumatic experience (stronger for noncombat interpersonal violence and accidents than for combat exposure), amount of time elapsed (stronger for less time between the event and PTSD assessment), and method of assessment for PTSD symptoms or diagnosis (stronger for interview studies than for self-reported measures) (Ozer et al., 2003). In an Australian study of people involved in motor vehicle incidents and later hospitalized, a personal history of psychiatric treatment was significantly associated with all trauma measures, including PTSD symptoms, 6 months after the event (Jeavons et al., 2000). In a meta-analysis of 22 studies, psychiatric history was found to be a significant predictor of PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000b).

Many studies have documented the association between PTSD and suicide ideation, attempts, and completions. In a study of civilians who had chronic PTSD and were attending a clinic, Tarrier and Gregg (2004) found that 38.3% reported suicide ideation and 9.6% reported having made a suicide attempt since experiencing the traumatic event. A comparison of those results with the NCS suggested higher suicidal tendencies among persons who had PTSD. Further support for the finding comes from a study by Marshall et al. (2001), who showed a linear increase in current suicide ideation with increased number of PTSD symptoms.

PTSD and drug or alcohol use is often associated. The lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders in NCS participants who had PTSD was more than twice that in people who did not have PTSD—a significant finding overall and also in comparing men with women. Comparing men who had PTSD to those who did not have PTSD, the odds ratio (OR) for having comorbid alcohol abuse or dependence was 2.06 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.14–3.70), and the OR was 2.97 (95% CI 1.52–5.79) for comorbid drug abuse or dependence; for women, the ORs were 2.48 (95% CI 1.78–3.45) and 4.46 (95% CI 3.11–6.39), respectively (Kessler et al., 1995). In an in-depth investigation of three possible causal pathways linking PTSD and drug use disorders, which included a longitudinal design of a randomly selected sample in a health maintenance organization in Michigan, Chilcoat and Breslau (1998) suggested that the most plausible pathway was self-medication. In this pathway, PTSD-affected persons are thought to

initiate use of drugs and other psychoactive substances use after symptom development to cope with and manage their memories and symptoms of PTSD (Brown and Wolfe, 1994; Khantzian, 1985; Stewart, 1996). That hypothesis was supported by the finding that people who had a history of PTSD were four times more likely to have drug use or dependence than those who did not have a PTSD diagnosis (Chilcoat and Breslau, 1998).

In civilian studies of smoking and psychiatric disorders, on the basis of data from the Tobacco Supplement of the NCS, current psychiatric disorders were found to increase the risk of onset of daily smoking in nonsmok-ers. In current smokers, the disorders were found to increase the risk of progression to nicotine dependence (Breslau et al., 2004). Another analysis of NCS smoking data found that the rates of current and lifetime smoking in people who had current and lifetime mental illness were significantly higher than in those who never reported having a mental illness. The study also concluded that people who have mental illness are twice as likely to smoke as those who do not (Lasser et al., 2000). Similarly, studies of the Vietnam-era twins cohort have concluded that active PTSD increased the risk of smoking independently of genetic makeup (Koenen et al., 2006) and that pre-existing nicotine dependence increased the risk of PTSD in male veterans (Koenen et al., 2005b).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF PTSD IN MILITARY AND VETERAN POPULATIONS

This section first describes the change in demographic profile and different stressors and trauma faced by members of the military since the Vietnam War. The epidemiology of PTSD in active-duty, National Guard, and reserve military populations and in veteran populations is then presented. Finally, some special considerations of PTSD in the military and veteran populations and their implications for screening, diagnosis, and treatment are highlighted.

Military-Related Stressors and Trauma

The current military population and veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) differ from military personnel and veterans of other eras, such as those of the Vietnam War and the 1990–1991 Gulf War. One of the largest differences between the military in the Vietnam War and in OEF and OIF is selection into military service. Roughly one-third of Vietnam service members were drafted, whereas the military in OEF and OIF is all volunteer. Demographics of the military (and therefore veteran) population have also changed since the Vietnam War. The female-to-male ratio has increased; only 0.2% of service

members in Vietnam were women compared with 12.7% of the deployed force in OEF and OIF (Maguen et al., 2010). Currently, 15.5% of all military personnel and nearly one-fourth of Army reserves are women (DoD, 2010). The racial and ethnic composition of the military has also evolved since the 1960s: 87% of military personnel in Vietnam were non-Hispanic white compared with 75% of current personnel (DoD, 2008).

Stressors and traumatic events have likewise shifted over time. As chronicled in detail in the Institute of Medicine Gulf War and Health series, stressors experienced by 1990–1991 Gulf War combat troops included uncertainty about possible exposures to chemical and biologic weapons, environmental exposures (such as to oil-well fire smoke and petroleum-based combustion products), incomplete knowledge of enemy troops, the harsh desert climate, separation from family, and crowded and difficult living conditions (for example, lack of privacy, infrequent access to hot water and laundry facilities, and constant vigilance for scorpions and snakes) (IOM, 2008a, 2010). OEF and OIF are occurring in a similar geographic location, and service members are subject to many of the same stressors. However, one of the largest differences between the current conflicts and prior engagement in the Middle East is the increasing number of insurgent attacks in the form of suicide bombs and car bombs, improvised explosive devices, sniper fire, and rocket-propelled grenades. Attacks are difficult to predict, often occurring in civilian areas where identification of enemy combatants is extremely challenging. As such, service members face increased risks of being wounded and killed and consequent exacerbation of the psychologic stressors that they experience. In contrast with the 1990–1991 Gulf War, where most military personnel were deployed for 9 months or less, troops deployed in OEF and OIF are subject to longer and repeated deployments with shorter rest and recovery times between deployments (MacGregor et al., 2012; Wieland et al., 2010). A recent study that examined the association between dwell time—the time between the end of one deployment and the start of the next—and diagnosed mental health disorders in more than 65,000 marines deployed to OIF found that those with two deployments had significantly higher rates of PTSD only, PTSD with another mental health disorder, and other mental health disorders than marines deployed only once. Further, longer dwell time—at least two times longer than the period of deployment—was associated with significantly reduced odds of PTSD (MacGregor et al., 2012). With the conflict in Iraq having ended and the conflict in Afghanistan expected to wind down, more service members will be returning home; as a result, the number seeking treatment for psychologic issues is expected to increase.

In addition to the many stressors encountered by service members while serving in the military, there are protective factors specific to military service that should not be overlooked. Unit cohesion, the close bond and culture

of interdependence developed among groups of service members (Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008), has been cited as one of the most important factors for preventing mental problems (Helmus and Glenn, 2004). See Chapter 5 for more discussion on risk and protective factors.

Epidemiologic Studies of Military and Veteran Populations

Estimates of lifetime PTSD prevalence in service members deployed to OEF and OIF are two to three times those in the general population. Estimates of current prevalence of PTSD in OEF and OIF service members range from 13% to 20% (Hoge et al., 2004; Seal et al., 2007; Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008; Vasterling et al., 2010). In a survey of 18,305 Army veterans who had returned from Iraq or Afghanistan, Thomas et al. (2010) found the PTSD prevalence at 3 months after deployment to be 7.7% in the active component and 6.7% in National Guard members and at 12 months to be 8.9% and 12.4%, respectively, on the basis of a strict definition of PTSD with serious functional impairment. Results of the NVVRS, conducted in 1988 with a representative sample of 1,200 veterans, found that 30.9% of men who served in Vietnam had developed PTSD at some point and 15.2% were currently living with it (Kulka, 1990). A reanalysis of the NVVRS by Dohrenwend et al. (2006) found reduced rates: an estimated lifetime PTSD prevalence of 18.7% and a current prevalence (when the survey was originally conducted) of 9.1%. Despite the difference, the prevalence of PTSD in the veteran population is still several times higher than that observed in the general population.

A study of 103,788 returning OEF and OIF veterans seen in VA health care facilities during September 2001–December 2005 showed that nearly one-third of them received at least one mental health or psychosocial diagnosis, and 13% of them had a diagnosis of PTSD (Seal et al., 2007). It is estimated that 23% to 40% of service members and veterans in need of mental health services receive care (Hoge et al., 2004); therefore, estimates of mental health burden based on service records probably underestimate the burden in these populations.

Combat Stress Severity

Known risk factors for PTSD specific to military populations include experiencing combat, high combat severity, being wounded or injured, witnessing death (especially grotesque death), serving on graves registration duty or handling remains, being taken captive or tortured, experiencing unpredictable and uncontrollable stressful exposure, experiencing sexual harassment or assault, combat preparedness, and deployment to a war zone without combat (IOM, 2007). In the NCS, 38% of men who had experienced

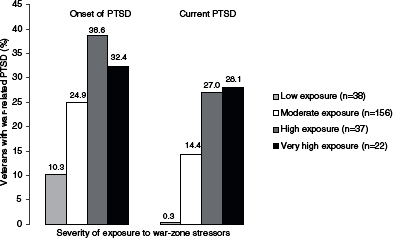

combat-related trauma had PTSD (Kessler et al., 1995). A positive dose–response relationship between severity of combat stressor exposure and clinically diagnosed PTSD was found in the NVVRS (see Figure 2-1). In addition to experiencing combat-related traumas, having experienced sexual assault while in the military is also of concern, especially in women. In the nationally representative VA Women’s Health Project, 55% of the female veterans in ambulatory care reported being sexually harassed, and 23% reported being sexually assaulted while they were in the military (Skinner et al., 2000).

Many studies assessing PTSD onset and duration in service members have used the 1990–1991 Gulf War veteran population because that war was the first large U.S. military engagement undertaken after PTSD was officially recognized as a psychologic disorder in 1980. During the 9-month conflict, about 697,000 U.S. military personnel were deployed to the Persian Gulf. In a large survey of Gulf War deployed veterans compared with era veterans from all services, 12.1% of those deployed had a diagnosis of PTSD compared with 4.3% of era veterans, and the risk of PTSD increased as a function of stress severity. Of those who had experienced minimal stress (were activated but not deployed or not activated reservists), 3.3%

FIGURE 2-1 Dose–response relationship of combat severity and clinically diagnosed PTSD.

SOURCE: Dohrenwend et al., 2006; reprinted with permission from AAAS.

had a diagnosis of PTSD, whereas 22.6% of those who were classified as having experienced high stress (having worn chemical protective gear, been involved in combat, or witnessed death) received the diagnosis (Kang et al., 2003). In the same sample population 10 years after the war, 6.2% of deployed veterans and 1.1% of nondeployed veterans had received a diagnosis of service-related PTSD (Toomey et al., 2007).

Sex

Although women are prohibited from serving in direct ground combat, they are subject to combat exposure while deployed. Of 329,049 OEF and OIF veterans who received care at a VA health care facility, females were significantly less likely than their male counterparts to receive a diagnosis of PTSD (17% vs. 22%, respectively) but significantly more likely to receive a diagnosis of depression (23% vs. 17%, respectively) (Maguen et al., 2010). Although Vogt et al. (2011) found that men were significantly more likely to report combat-related stressors (such as combat exposure, aftermath of battle, and difficult living environment), no sex differences were found in combat-associated stressors for predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms. In a sample of National Guard service members 1 month before deployment, no differences between males and females were found in posttraumatic stress symptoms (mean scores on the PTSD Checklist— Civilian version were 26.0 and 27.4, respectively) although females were significantly more likely to screen positive for depression symptoms (mean scores on the Beck Depression Inventory-II were 5.6 for men and 9.5 for women) (Carter-Visscher et al., 2010). Similarly, in a study of OEF and OIF veterans seen in VA health care facilities from 2001 through 2005, women and men were equally likely to receive at least one mental health diagnosis (26% and 25%, respectively), but men were significantly more likely to receive a diagnosis of PTSD (risk ratio 1.14, 95% CI 1.08–1.10) (Seal et al., 2007). However, in a prospective study that used a deployed and nondeployed Millennium Cohort sample, new onset of self-reported PTSD symptoms was proportionally higher in women than in men overall (3.8% and 2.4%, respectively) and significantly higher after stratification by service branch, except for the marines (Smith et al., 2008).

Age

Unlike the civilian population, in which 16.7% of people are 18–29 years old (Howden and Meyer, 2011), more than 60% of active-duty service members are 30 years old or younger (DoD, 2008). In a study of mental health diagnoses in OEF and OIF veterans seen in VA health care facilities in 2001–2005, veterans 18–24 years old had the highest risk of

receiving a diagnosis of PTSD, followed by the 30–39-year age group and the 25–29-year age group, compared with veterans 40 years and older (Seal et al., 2007).

Sexual Assault

Sexual assault is a leading risk factor for PTSD (Kessler et al., 1995). Prevalence estimates vary by method of assessment, sample type (clinical, research, or benefit-seeking), and definition used (Suris and Lind, 2008). Military sexual trauma (MST) is a term used specifically in the VA and is defined as “sexual harassment that is threatening in character or physical assault of a sexual nature that occurred while the victim was in the military, regardless of geographic location of the trauma, gender of the victim, or the relationship to the perpetrator” (VA, 2012). MST surveillance data collected by the VA on nearly 1.7 million veterans showed that about 22% of women and 1% of men experienced MST. However, it has been estimated that about 54% of all VA users that screen positive for MST are men (Suris and Lind, 2008). Other convenience and small-sample studies of experiencing rape and sexual assault during military service have estimated the prevalence in women to range from 23% to 41% (Coyle et al., 1996; Frayne et al., 1999; Sadler et al., 2000). In a small study of female veterans that compared MST with other types of trauma, 60% of those who reported MST had received a diagnosis of PTSD compared with 43% of those who experienced other traumas (with or without MST) (Yaeger et al., 2006). In a follow-up analysis, MST was compared with nonmilitary sexual trauma for predicting PTSD. Although sexual trauma is significantly associated with PTSD, MST was more likely to result in PTSD than sexual assault occurring outside of military service (Himmelfarb et al., 2006). In a small convenience sample of female veterans, Suris et al. (2004) found that women who had a history of sexual assault were nine times more likely to have PTSD than women who did not experience sexual assault. In a large sample of deployed OEF and OIF veterans who separated from the military by October 2006 and later used VA health care services, 15.1% of females and 0.7% of males screened positive for MST. Women who screened positive for MST were 3.8 times more likely than women who did not report MST to receive a diagnosis of PTSD. Men who screened positive for MST were 2.5 times more likely than men who did not to receive a diagnosis of PTSD (Kimerling et al., 2010).

Race

In a large sample of OEF and OIF veterans seen at VA health care facilities over a 4-year period, Seal et al. (2007) found that blacks were more

likely to receive a diagnosis of PTSD than other racial or ethnic groups. In a subsample of the NVVRS, Dohrenwend et al. (2008) examined racial differences in current (chronic) PTSD attributed to service in the military. Black veterans’ high prevalence of PTSD was explained by their greater exposure to war-zone stressors, and Hispanic veterans’ higher prevalence of current PTSD was explained by several factors, including younger age at deployment to Vietnam, lower education, and lower Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) scores. A subsample of the NVVRS found that the higher prevalence of chronic PTSD in Hispanic veterans persists after adjustment for exposure to war-zone stressors. Levels of impairment due to current PTSD in those Hispanic veterans were not statistically different from those in other racial groups; this suggests that cultural factors of “greater expressiveness” cannot explain the higher prevalence of PTSD in this population (Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2008).

IQ

As lower IQ scores have been associated with increased risk of developing PTSD in the civilian population, so are lower scores on the AFQT associated with increased risk of PTSD. Some researchers have argued that low IQ and other cognitive deficits may be sequelae of PTSD (De Bellis, 2001), but prospective studies of military samples that have used measures of cognitive ability from military records (for example, the AFQT) show that premilitary IQ is inversely associated with risk of combat-related PTSD (Kremen et al., 2007; Macklin et al., 1998; Pitman et al., 1991). In a study of veterans exposed to potentially traumatic events recruited from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry after controlling for confounders, persons who had the highest AFQT scores (76–99 and 56–75) had significantly less risk of PTSD than persons who had the lowest category of AFQT scores (0–33) (Kremen et al., 2007). In a large-scale prospective study of a military sample, Gale et al. (2008) replicated the link between low IQ and PTSD but found a stronger link between low IQ and PTSD with comorbidities, including generalized anxiety disorder and substance abuse or dependence. Those results suggest that the severity of the psychiatric disorder may play a role in the IQ–PTSD link.

Psychopathology

Premilitary psychopathology is also a risk factor for PTSD in military populations. Data from the NVVRS (Kulka, 1990) and the Vietnam Era Twin Registry suggest that negative juvenile conduct increases the risk of both level of combat and PTSD (Fu et al., 2007; Koenen et al., 2002, 2005a). Those results are similar to those of prospective civilian studies

that found that externalizing behavior problems in childhood increase the risk of PTSD in adulthood (Gregory et al., 2007; Koenen et al., 2007). The findings are further supported by a meta-analysis of seven military or veteran population studies that associated adverse childhood risk factors with PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000b).

Koenen et al. (2002) examined familial and individual risk factors and their associations with exposure to trauma and PTSD in a cohort of Vietnam era twins. Although a family history of mood disorders was associated with increased risk of exposure to traumatic events, people who had a pre-existing mood disorder were less likely to be exposed to traumatic events. Family history of paternal depression and pre-existing psychologic disorders (conduct disorder, panic or generalized anxiety disorder, and major depression) were all associated with an increased risk of PTSD. Those findings suggest that the association of family psychiatric history and PTSD may be mediated by individual-level risks of traumatic exposure and preexisting psychologic disorders (Koenen et al., 2002).

Genetics

Several studies of Vietnam Era Twin Registry data have also shown associations between familial risk factors and PTSD. In one study that examined genetic and environment effects on conduct disorder, major depression, and PTSD, Fu et al. (2007) found that the three outcomes correlated strongly. Those who had a history of conduct disorder or major depression were more likely to have a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD than those who did not have such a history. Although there was no genetic covariance between conduct disorder and PTSD, common genetic influences alone could be attributed to the association between major depression and PTSD. Koenen et al. (2008a) examined the genetic and individual-specific environmental correlation between comorbid major depression and PTSD in Vietnam veterans. Environmental influences did not explain much of the comorbid correlation, but shared genetic factors explained 62.5% of comorbid major depression and PTSD. Furthermore, genetic influences common to major depression explained 58% of the genetic variation in PTSD; this suggests that genes associated with one of these disorders are good candidates for studies of the other disorder. In a related study of genetic and environmental associations of internalizing and externalizing dimensions of psychiatric comorbidity in Vietnam veteran twins, specifically PTSD, Wolf et al. (2010) found that shared genetic factors explained a significant proportion of variance for both internalizing and externalizing comorbidity. Although the authors found greater genetic association with the internalizing spectrum and only modest genetic association with the externalizing factors and PTSD, commonly shared or experienced factors (including immediate family

environment and socioeconomic status) may influence the externalizing psychopathology, which may then influence the expression of psychiatric conditions, such as PTSD.

Comorbidities of PTSD

Comorbid conditions—including depressive symptoms, alcohol use, and other high-risk behaviors—are present in more than 50% of OEF and OIF veterans who have PTSD (Hoge et al., 2004; Santiago et al., 2010). Recent estimates of PTSD and substance use disorders in military populations have varied. In a study of 151 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who were seeking primary care, 39.1% screened positive for PTSD only and 15.9% screened positive for alcohol problems and PTSD, and PTSD symptoms and severity of alcohol problems correlated significantly (McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2010). Using a VA medical database of OEF and OIF veterans enrolled in VA services from 2001 to 2006, Stecker et al. (2010) found that 12.0% had a PTSD-only diagnosis and 4.2% had a diagnosis of PTSD and alcohol misuse. The authors suggest that the rate probably underreported substance use disorders greatly.

Several studies of combat experience in the Vietnam War have also found higher proportions of suicide ideation, attempts, and completions among those who have PTSD (Farberow et al., 1990; Fontana and Rosenheck, 1995; Hendin and Haas, 1991; Kramer et al., 1994). Those findings are of particular importance in light of the large numbers of service members that have served in OEF and OIF and have had a diagnosis of PTSD; the number of suicides among active-duty and reserve service members has continued to rise since the beginning of the conflicts. A study that examined PTSD as a risk factor for suicidal ideation among 407 OEF and OIF veterans who were referred to the VA health care system for mental health services found that veterans who screened positive for PTSD were about 4.5 times more likely to report suicidal ideation than veterans who did not have PTSD (Jakupcak et al., 2009). Furthermore, among the 202 veterans that screened positive for PTSD, those who also screened positive for two or more comorbid disorders were 5.7 times more likely to report suicidal ideation that those who had fewer comorbidities (Jakupcak et al., 2009). Beginning in 2003, DoD Mental Health Advisory Teams have been conducting mental health surveillance for service members in Iraq and Afghanistan combat environments. Although the most recent report shows the percentage of positive responses to a question about suicide ideation among Army and Marine Corps personnel is unchanged from previous survey results, there have been significant increases in the adjusted percentage of those who report acute stress (MHAT VII, 2011).

Special Considerations

Many unique concerns surround the diagnosis of and treatment for PTSD in the military, particularly service members and veterans who have served in OEF and OIF. Some of the concerns pertain to time in the theater of war and the traumatic events that service members experience there, such as traumatic brain injury, physical wounds, experience of firefights, and the deaths of close companions. The effects of those will be discussed further in Chapter 8. Societal and cultural influences (Lewis-Fernandez et al., 2010) and premorbid factors peculiar to military populations also affect diagnosis and treatment course. Chapter 9 elaborates on the particular barriers to PTSD care in military populations, and Chapter 8 discusses the challenges to rehabilitation that result from the comorbidity of PTSD with other psychiatric illnesses in military populations. The present section addresses issues that are of concern to members of the military who have PTSD.

Underrecognized and Underreported

The true prevalence of PTSD in military populations is probably higher than the available estimates. Generally, prevalence estimates for PTSD in the populations have ranged from 13% to 20% (Hoge et al., 2004; Seal et al., 2007; Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008; Vasterling et al., 2010). However, those may be underestimates of the prevalence of PTSD in the military and veteran populations. The fear of negative consequences for a military career, including decreased potential for promotion and perceived stigma by peers and leaders (Hoge et al., 2004), may lead to underreporting of PTSD symptoms.

Despite rigorous screening efforts by the DoD, underreporting of symptoms may be common. In one study by Warner et al. (2011), a brigade of Army soldiers first completed the post-deployment health assessment (PDHA) on returning from Iraq, and a subsample completed an anonymous survey that consisted of the same mental health questions as were on the PDHA. The number of positive responses to the mental health questions overall and to the PTSD-specific questions more than doubled, and in some cases quadrupled, in the anonymous survey (7.7% screened positive) compared with the PDHA (3.3% screened positive); of those who screened positive for either PTSD or depression on the anonymous survey, 20.3% reported that they were not comfortable in reporting their answers honestly on the PDHA. Those results indicate a high level of underreporting of mental health symptoms, which may have negative implications for the health and readiness of the armed forces.

The positive-screen group from the Warner et al. (2011) study also indicated they were less likely to seek treatment for these issues (one-third

believing that it would harm their careers) than the group that screened negative for PTSD or depression. Kim et al. (2010) found that active-duty service members who had been deployed were less likely to use mental health services for any reported mental health problems and were more conscious of a stigma associated with seeking care than National Guard members who had been deployed. This underutilization of treatment is another barrier to the effective treatment of PTSD (see Chapters 6 and 9 for additional discussion).

A diagnosis of PTSD may be more likely in a particular military population. For example, in a sample of combat-injured and non–combat-injured service members in OIF, those who had more serious injuries and those whose injuries were related to combat were more likely to have a diagnosis of PTSD than were service members who had less serious injuries and injuries that were not combat related (MacGregor et al., 2009). Thus, although the DoD and the VA mandate population screening for PTSD, its prevalence is probably underreported.

Nomenclature

One source of PTSD-associated stigma in the military may be the name itself (Nash et al., 2009). General Peter Chiarelli, the Army vice chief of staff and second-highest ranking Army officer, stated that the word disorder itself is problematic and carries a stigma that has discouraged many soldiers from seeking treatment (Sagalyn, 2011). General Chiarelli has proposed a change to “posttraumatic stress injury” to encourage afflicted soldiers and their commanders to support the importance of diagnosis and treatment. Veterans’ service organizations have concurred in the name change. One reason that disorder was kept as part of the name of this condition when it was first included in the DSM-III was to legitimatize the pain and suffering of Vietnam War veterans (Sagalyn, 2011). However, there are several arguments against the name change, such as PTSD afflicts many persons, not only service members; removing disorder could confuse normal and abnormal (in need of treatment) responses to stress; and the belief that PTSD will be stigmatized no matter what it is called. Despite the controversy, there is no plan to change the name when the next version of the DSM is released.

Healthy Warrior Effect

The “healthy worker effect” suggests that employed persons generally have lower rates of serious illnesses, disabilities, and deaths than the general population because their better health status allows them to gain employment and remain employed. The “healthy warrior effect” is an extension of this concept (Arrighi and Hertzpicciotto, 1994). People who have poor

physical health are unlikely to join the armed forces or to complete basic training, and the same should be true of people who have poor mental health. If such people are not medically discharged early in their military careers, they may be excluded from some deployments (Wilson et al., 2009).

Subthreshold PTSD

As discussed earlier in this chapter, DSM-IV lists 17 symptoms of PTSD, at least 6 of which are required—in the correct distribution (one re-experiencing, three numbing or avoidance, and two hyperarousal)—for a diagnosis of PTSD. However, several studies have indicated that even sub-threshold PTSD is impairing and that people who have it may benefit from treatment (Grubaugh et al., 2005; Marshall et al., 2001; Stein et al., 1997; Zlotnick et al., 2002). If the purpose of diagnosing PTSD and treating it is to regain and maintain functioning, then it is clear that any symptoms that are potentially attributable to prior trauma and are accompanied by functional impairment warrant treatment. Subthreshold PTSD may also be a signal of other pathologic conditions, such as depression or an additional anxiety disorder, in that there is overlap in the defining symptoms of these conditions. Subthreshold symptoms have potential implications for screening, level of functioning, degree of distress, and treatment. A full discussion of the implications of subthreshold PTSD is beyond the scope of this report, but it merits mention as a subject of further inquiry.

Compensation Issues and Secondary Gain

PTSD in military and veteran populations is complicated by concerns about malingering and attempts to receive the diagnosis for secondary gain. This issue has become particularly important in military populations inasmuch as its presence is formally recognized as making someone eligible for DoD and VA benefits. Thus, a diagnosis of PTSD is problematic in both active-duty and veteran populations, and can lead to underreporting (for example, to remain in one’s position) or to overreporting (for example, to gain benefits or to be excused from duty). A previous Institute of Medicine report on PTSD compensation and military service (IOM, 2007) noted that, apart from problems with the current procedures for assigning a disability rating to PTSD, other considerations include “barriers or disincentives to recovery, the effect of disability compensation on recovery, and the advisability of periodic re-examination of PTSD compensation beneficiaries.” Although that committee found that compensation does not appear to serve as a disincentive to seeking treatment, periodic re-examinations for veterans who have a PTSD service-connected disability were regarded as inappropriate because research on misreporting and exaggeration of symptoms had

not found evidence supporting a singling out of PTSD (IOM, 2007). This is an important and complicated issue, and the present committee will reconsider it if any new literature becomes available during phase 2.

PTSD is prevalent in the general population in which it has a lifetime prevalence of about 8% in adults, but military and veteran populations are exposed to many more traumatic events than the general population, and service members who have served in OEF and OIF have a lifetime PTSD prevalence of 13% to 20%. Many factors increase a service member’s risk of PTSD, some demographic—such as age; sex; prior exposure to trauma, particularly sexual assault and childhood maltreatment; lower education attainment; and lower IQ—and some combat-specific—such as killing someone, seeing someone killed, and being in an explosion or being badly injured. PTSD is often comorbid with other psychologic or medical conditions, such as depression, substance use (particularly alcohol use) disorder, and traumatic brain injury. Special considerations in the diagnosis of and treatment for PTSD in military and veteran populations include subthreshold PTSD, underreporting and overreporting of PTSD symptoms, the role of stigma in seeking care for PTSD, the healthy warrior effect, and compensation. The next chapter provides a discussion of the biologic basis of and factors that affect the development of PTSD.

APA (American Psychiatric Association). 1980. DSM-III: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

APA. 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Arrighi, H. M., and I. Hertzpicciotto. 1994. The evolving concept of the healthy worker survivor effect. Epidemiology 5(2):189-196.

Barnett, J. H., C. H. Salmond, P. B. Jones, and B. J. Sahakian. 2006. Cognitive reserve in neuropsychiatry. Psychological Medicine 36(8):1053-1064.

Basile, K. C., I. Arias, S. Desai, and M. P. Thompson. 2004. The differential association of intimate partner physical, sexual, psychological, and stalking violence and posttraumatic stress symptoms in a nationally representative sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress 17(5):413-421.

Batty, G. D., E. L. Mortensen, and M. Osler. 2005. Childhood IQ in relation to later psychiatric disorder: Evidence from a Danish birth cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry 187:180-181.

Birmes, P., L. Hatton, A. Brunet, and L. Schmitt. 2003. Early historical literature for post-traumatic symptomatology. Stress and Health 19(1):17-26.

Boscarino, J. A. 2008. A prospective study of PTSD and early-age heart disease mortality among Vietnam veterans: Implications for surveillance and prevention. Psychosomatic Medicine 70(6):668-676.

Breslau, N., and E. L. Peterson. 2010. Assaultive violence and the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder following a subsequent trauma. Behaviour Research and Therapy 48(10): 1063-1066.

Breslau, N., G. C. Davis, P. Andreski, and E. Peterson. 1991. Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 48(3):216-222.

Breslau, N., G. C. Davis, and P. Andreski. 1995. Risk factors for PTSD-related traumatic events: A prospective analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(4):529-535.

Breslau, N., R. C. Kessler, H. D. Chilcoat, L. R. Schultz, G. C. Davis, and P. Andreski. 1998. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community—the 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry 55(7):626-632.

Breslau, N., G. C. Davis, and L. R. Schultz. 2003. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the incidence of nicotine, alcohol, and other drug disorders in persons who have experienced trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry 60(3):289-294.

Breslau, N., S. P. Novak, and R. C. Kessler. 2004. Daily smoking and the subsequent onset of psychiatric disorders. Psychological Medicine 34(2):323-333.

Breslau, N., V. C. Lucia, and G. F. Alvarado. 2006. Intelligence and other predisposing factors in exposure to trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A follow-up study at age 17 years. Archives of General Psychiatry 63(11):1238-1245.

Breslau, N., E. L. Peterson, and L. R. Schultz. 2008. A second look at prior trauma and the posttraumatic stress disorder effects of subsequent trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry 65(4):431-437.

Brewin, C. R., B. Andrews, and S. Rose. 2000a. Fear, helplessness, and horror in posttraumatic stress disorder: Investigating DSM-IV criterion A2 in victims of violent crime. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13(3):499-509.

Brewin, C. R., B. Andrews, and J. D. Valentine. 2000b. Meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68(5):748-766.

Bromet, E., A. Sonnega, and R. C. Kessler. 1998. Risk factors for DSM-III-R posttraumatic stress disorder: Findings from the national comorbidity survey. American Journal of Epidemiology 147(4):353-361.

Brown, P. J., and J. Wolfe. 1994. Substance abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbid-ity. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 35(1):51-59.

Carter-Visscher, R., M. A. Polusny, M. Murdoch, P. Thuras, C. R. Erbes, and S. M. Kehle. 2010. Predeployment gender differences in stressors and mental health among U.S. National Guard troops poised for Operation Iraqi Freedom deployment. Journal of Traumatic Stress 23(1):78-85.

Chantarujikapong, S. I., J. F. Scherrer, H. Xian, S. A. Eisen, M. J. Lyons, J. Goldberg, M. Tsuang, and W. R. True. 2001. A twin study of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms, panic disorder symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder in men. Psychiatry Research 103:133-145.

Chilcoat, H. D., and N. Breslau. 1998. Investigations of causal pathways between PTSD and drug use disorders. Addictive Behaviors 23(6):827-840.

Cohen, B. E., C. Marmar, L. Ren, D. Bertenthal, and K. H. Seal. 2009. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with mental health diagnoses in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans using VA health care. Journal of the American Medical Association 302(5):489-492.

Cohen, B. E., P. Panguluri, B. Na, and M. A. Whooley. 2010. Psychological risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in patients with coronary heart disease: Findings from the heart and soul study. Psychiatry Research 175(1-2):133-137.

Coyle, B. S., D. L. Wolan, and A. S. Van Horn. 1996. The prevalence of physical and sexual abuse in women veterans seeking care at a Veterans Affairs medical center. Military Medicine 161(10):588-593.

De Bellis, M. D. 2001. Developmental traumatology: The psychobiological development of maltreated children and its implications for research, treatment, and policy. Development and Psychopathology 13:539-564.

Desai, S., I. Arias, M. P. Thompson, and K. C. Basile. 2002. Childhood victimization and subsequent adult revictimization assessed in a nationally representative sample of women and men. Violence & Victims 17(6):639-653.

Dirkzwager, A. J., P. G. van der Velden, L. Grievink, and C. J. Yzermans. 2007. Disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health. Psychosomatic Medicine 69(5):435-440.

Dobie, D. J., D. R. Kivlahan, C. Maynard, K. R. Bush, T. M. Davis, and K. A. Bradley. 2004. Posttraumatic stress disorder in female veterans: Association with self-reported health problems and functional impairment. Archives of Internal Medicine 164(4):394-400.

DoD (Department of Defense). 2008. Active duty demographic profile: Assigned strength, gender, race, marital, education and age profile of active duty force. Defense Manpower Data Center.

DoD. 2010. Demographics 2010: Profile of the military community. Washington, DC: Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense.

Dohrenwend, B. P., J. B. Turner, N. A. Turse, B. G. Adams, K. C. Koenen, and R. Marshall. 2006. The psychological risks of Vietnam for U.S. veterans: A revisit with new data and methods. Science 313(5789):979-982.

Dohrenwend, B. P., J. B. Turner, N. A. Turse, R. Lewis-Fernandez, and T. J. Yager. 2008. War-related posttraumatic stress disorder in black, Hispanic, and majority white Vietnam veterans: The roles of exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Traumatic Stress 21(2):133-141.

Dong, M., W. H. Giles, V. J. Felitti, S. R. Dube, J. E. Williams, D. P. Chapman, and R. F. Anda. 2004. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: Adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation 110(13):1761-1766.

Farberow, N. L., H. K. Kang, and T. A. Bullman. 1990. Combat experience and postservice psychosocial status as predictors of suicide in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 178(1):32-37.

Fontana, A., and R. Rosenheck. 1995. Attempted suicide among Vietnam veterans: A model of etiology in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(1):102-109.

Frayne, S. M., K. M. Skinner, L. M. Sullivan, T. J. Tripp, C. S. Hankin, N. R. Kressin, and D. R. Miller. 1999. Medical profile of women Veterans Administration outpatients who report a history of sexual assault occurring while in the military. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine 8(6):835-845.

Friedman, M., P. A. Resick, R. A. Bryant, and C. R. Brewin. 2010. Considering PTSD for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety 1(20).

Fu, Q., K. C. Koenen, M. W. Miller, A. C. Heath, K. K. Bucholz, M. J. Lyons, S. A. Eisen, W. R. True, J. Goldberg, and M. T. Tsuang. 2007. Differential etiology of posttraumatic stress disorder with conduct disorder and major depression in male veterans. Biological Psychiatry 62(10):1088-1094.

Gale, C. R., I. J. Deary, S. H. Boyle, J. Barefoot, L. H. Mortensen, and G. D. Batty. 2008. Cognitive ability in early adulthood and risk of 5 specific psychiatric disorders in middle age: The Vietnam experience study. Archives of General Psychiatry 65(12):1410-1418.

Galea, S., and H. Resnick. 2005. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the general population after mass terrorist incidents: Considerations about the nature of exposure. CNS Spectrums 10(2):107-115.

Galea, S., D. Vlahov, H. Resnick, J. Ahern, E. Susser, J. Gold, M. Bucuvalas, and D. Kilpatrick. 2003. Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology 158(6):514-524.

Galea, S., D. Vlahov, M. Tracy, D. R. Hoover, H. Resnick, and D. Kilpatrick. 2004. Hispanic ethnicity and post-traumatic stress disorder after a disaster: Evidence from a general population survey after September 11, 2001. Annals of Epidemiology 14(8):520-531.

Galea, S., J. Ahern, M. Tracy, A. Hubbard, M. Cerda, E. Goldmann, and D. Vlahov. 2008. Longitudinal determinants of posttraumatic stress in a population-based cohort study. Epidemiology 19(1):47-54.

Gregory, A. M., A. Caspi, T. E. Moffitt, K. Koenen, T. C. Eley, and R. Poulton. 2007. Juvenile mental health histories of adults with anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 164(2):301-308.

Grubaugh, A. L., K. M. Magruder, A. E. Waldrop, J. D. Elhai, R. G. Knapp, and B. C. Frueh. 2005. Subthreshold PTSD in primary care: Prevalence, psychiatric disorders, healthcare use, and functional status. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 193(10):658-664.

Harrison, C. A., and S. A. Kinner. 1998. Correlates of psychological distress following armed robbery. Journal of Traumatic Stress 11(4):787-798.

Harvard Medical School. 2007a. 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_12-month_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf (accessed January 10, 2011).

Harvard Medical School. 2007b. Lifetime prevalence DSM-IV/WMH-CIDI disorders by sex and cohort (n=9282). http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/ftpdir/NCS-R_Lifetime_Prevalence_Estimates.pdf (accessed January 10, 2011).

Helmus, T. C., and R. W. Glenn. 2004. Steeling the mind: Combat stress reactions and their implications for urban warfare. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Hendin, H., and A. P. Haas. 1991. Suicide and guilt as manifestations of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry 148(5):586-591.

Himmelfarb, N., D. Yaeger, and J. Mintz. 2006. Posttraumatic stress disorder in female veterans with military and civilian sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 19(6):837-846.

Hoge, C. W., C. A. Castro, S. C. Messer, D. McGurk, D. I. Cotting, and R. L. Koffman. 2004. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 351(1):13-22.

Holbrook, T. L., D. B. Hoyt, M. B. Stein, and W. J. Sieber. 2001. Perceived threat to life predicts posttraumatic stress disorder after major trauma: Risk factors and functional outcome. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care 51(2):287-292; discussion 292-283.

Howden, L. M., and J. A. Meyer. 2011. Age and sex composition: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2007. PTSD compensation and military service. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008a. Gulf War and health: Physiologic, psychologic, and psychosocial effects of deployment-related stress. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008b. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: An assessment of the evidence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2010. Gulf War and health: Update of health effects of serving in the Gulf War. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jakupcak, M., J. Cook, Z. Imel, A. Fontana, R. Rosenheck, and M. McFall. 2009. Posttrau-matic stress disorder as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress 22(4):303-306.

Jeavons, S., K. M. Greenwood, and D. J. Horne. 2000. Accident cognitions and subsequent psychological trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13(2):359-365.

Jones, E. 2006. Historical approaches to post-combat disorders. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 361(1468):533-542.

Kang, H. K., B. H. Natelson, C. M. Mahan, K. Y. Lee, and F. M. Murphy. 2003. Post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome-like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. American Journal of Epidemiology 157(2):141-148.