Leveraging Existing Services and Programs to Support Resilience

In researching the various components of resilience efforts, the planning committee wanted to explore how to potentially leverage existing programs and services. Speakers were invited to discuss two of the most common employee programs that are related to resilience—wellness programs and employee assistance programs (EAPs). Wellness programs are defined as organized, employer-sponsored programs that are designed to support employees (and, sometimes, their families) as they adopt and sustain behaviors that reduce health risks, improve quality of life, enhance personal effectiveness, and benefit the organization’s bottom line (Berry et al., 2010). EAPs are workplace programs designed to assist: (1) work organizations in addressing productivity issues and (2) “employee clients” in identifying and resolving personal concerns, including health, marital, family, financial, alcohol, drug, legal, emotional, stress, or other personal issues that may affect job performance (Rothermel, 2008). All Department of Homeland Security (DHS) components offer employees access to EAP services and many offer wellness programs.

The committee asked the speakers to discuss the available evidence supporting these types of programs and to offer suggestions to DHS on how they might leverage these services to support the resilience initiative in the future.

Ann Mirabito is a marketing professor at Baylor University and gave a presentation on wellness programs. Elizabeth Merrick is a researcher from Brandeis University and gave her presentation on EAPs. Following the presentations there was a panel discussion where Mirabito and Merrick addressed questions from various workshop participants. Planning committee member Scott Mugno moderated the panel discussion. While the

speakers looked at different types of services and programs, themes emerged in the presentations and discussion (see Box 6-1).

BOX 6-1

Themes from Individual Speakers on Leveraging Existing Services

- EAPs and wellness programs’ effectiveness and utilization are affected by:

- Leadership buy-in and support

- Alignment of programs with organizational culture

- Effective communications

- Performance measurement as a tool for improving interventions

- Employer returns on investment for EAPs and wellness programs

Dr. Ann Mirabito suggested that, despite different terminology, there is a strong relationship between wellness and resilience. She hoped that the wellness research can inform the discussion on workforce resilience and offer a pathway for possible interventions. Her presentation on workplace wellness drew from an in-depth study of 10 firms that have highly integrated comprehensive wellness programs. The study looked at a wide range of organizations in terms of size, depth of experience in wellness, and domestic or global reach. Mirabito and her colleagues distilled the information from the study into six pillars of effective workplace wellness programs. She also presented data that illustrated the business case for investing in wellness programs in terms of reduced health care costs and a stronger workforce (Berry et al, 2010).

Workplace Wellness

Mirabito defined workplace wellness as an organized employee-sponsored program designed to engage and support employees in adopting and sustaining behaviors that reduce health risks, improve the

quality of life, enhance personal effectiveness, and benefit the organization’s bottom line. Some of the programs also include family members. Workplace wellness bridges individual responsibility for health and well-being with institutional support.

Traditionally, when a firm is considered a healthy company it is in reference to its financial health. Mirabito suggested that the workplace wellness movement offers the opportunity to create a new meaning for the concept of a healthy company. Mirabito and her colleagues have found that the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of employees all contribute to a stronger organizational culture, increased productivity, and improved financial performance. Additionally, companies are finding that wellness programs are helping decrease costs.

Mirabito noted that effective workplace wellness requires a sustained commitment from the company because it involves encouraging employees to change from unhealthy habitual behaviors to risk-reducing behaviors. There are many reasons why employees choose not to participate in wellness programs such as a lack of awareness, time, and managerial support, no perceived benefit, inaccessibility, and privacy concerns. Therefore, developing an effective workplace wellness program is key (Berry et al., 2010).

The Six Pillars of Effective Workplace Wellness

The six pillars of effective workplace wellness distilled from the in-depth study are (1) multilevel leadership; (2) alignment; (3) scope, relevance, and quality; (4) accessibility; (5) partnerships; and (6) communications. The pillars are described below.

Multilevel Leadership

The first pillar of effective workplace wellness that Mirabito and her colleagues identified was multilevel leadership. At the executive level, effective leadership includes setting a personal example, providing sufficient resources, investing in high-quality managers to run the day-to-day wellness activities, overseeing the establishment of realistic goals and measurement of those goals, and sometimes making tough decisions. Most of all, it requires viewing wellness as a cultural and strategic imperative. Mirabito suggested that middle managers play a crucial role on a day-to-day basis of spreading and making the wellness program a success. The most effective programs incorporate a wellness module into

management education programs and also ensure that managers are aware of wellness program metrics.

Wellness Program Leadership Who is going to manage the program is an important decision for senior management. The very best wellness managers have the four Ps of wellness leadership—passion, persistence, patience, and persuasive leadership skills. Additionally, the wellness manager needs to be collaborative, analytical, credible by background and performance, and able to connect his or her personal wellness expertise to the culture and the overall strategy of the organization.

Wellness Champions Effective wellness programs benefit from a daily persuasive presence in the workplace through wellness champions. Wellness champions are employees in specific work units, like a department, and they volunteer to be an ambassador for the wellness program. The wellness champions offer local, on-the-ground encouragement and education. They mentor coworkers, handle administrative roles, know their clientele, and can request special programming from headquarters.

Alignment

Through her research, Mirabito found that companies who start wellness programs have to stay engaged in wellness if employee health changes are going to be sustained. Employers are going to continue their investment in workplace wellness only if wellness is aligned with the organization’s culture and business priorities. Wellness programs are also less vulnerable to spending cuts when they are aligned with business priorities, noted Mirabito. At Chevron, 60 to 70 percent of all jobs are considered safety-sensitive because employees put themselves or others at risk. Wellness is an integral part of the culture at Chevron, in part because the company has evidence to show that healthy workers are safer workers.

Scope, Relevance, and Quality

The third pillar is the scope, relevance, and quality of wellness programs. In terms of scope, wellness is not only about physical fitness but also about mental and emotional health. In particular, depression and stress prove to be major causes of loss of productivity and are therefore important wellness components. Employers must be prepared to invest in

high-quality wellness services or else the inevitable initial skepticism and resistance to the programs is going to grow rather than diminish.

Accessibility

The fourth pillar of effective workplace wellness is accessibility. Companies with excellent wellness programs make it very easy for employees to say yes to wellness. Health fairs are particularly effective in companies whose employees do not get regular care from a doctor. Fitness centers are a tangible symbol of the employer’s commitment to wellness. When employees see it and other people using it they are more likely to use it themselves.

Online tools can make it easier for employees to access wellness messages. However, Mirabito cautioned that while online tools are important, high tech must be balanced with high touch in order to connect employees in a culture of health.

Partnerships

Mirabito found that the wellness function in every organization included in the study is leanly budgeted and staffed. Wellness is all about formal and informal partnerships. The wellness staff are the cultural change agents. They rely on partnerships throughout the organization to cajole, teach, and facilitate unit managers and individual employees into becoming wellness activists. Mirabito suggested that vendor partnerships can leverage the very lean budgets and the lean staffs of most wellness initiatives.

Communications

The sixth pillar is communications. Mirabito suggested that wellness communications have a big challenge in overcoming individual apathy and the sensitivity factors in personal health issues. Employees are often culturally and demographically diverse, which can make messaging more complicated. Effective communications must be highly targeted. People like to get information in different ways, and effective communications need to use multiple media.

Returns on Investment for Workplace Wellness

Mirabito suggested that effective workplace wellness translates into employee engagement and improved health. This in turn, translates into health care cost improvements, productivity gains, and gains in the organizational culture. However, an effective wellness program needs to be established for the returns on investment to be possible. The focus here is on effective. The key to establishing an effective program is to have a culture of inclusiveness, collaboration, flexibility, nondiscrimination, and trust. Accountability has to flow both ways, from the employer to the employee and from the employee back to the employer.

As for health care cost savings, research has found that medical costs fall approximately $3.27 for every dollar that is spent on wellness programs, and that absentee costs fall about $2.73 for every dollar that is spent. It is important to know that this research does not address savings in presenteeism or other forms of productivity, which would likely show a higher return on investment (Baicker et al., 2010; Henke et al., 2011).

Mirabito and her colleagues developed a dashboard for measuring wellness program effectiveness. Their dashboard has two dimensions: (1) employee metrics of participation, satisfaction, and well-being; and (2) organizational measures of the financial, productivity, and cultural outcomes.

To implement evaluation, companies set goals based on these metrics, measure them, and then track them.

Dr. Elizabeth Merrick provided an overview of EAPs. Her comments covered three areas of interest: the services EAPs provide for both organizations and employees, how they relate to resilience, and the importance of building program evaluation into the program.

Defining Employee Assistance Programs

Merrick noted that there are many definitions of EAPs and that for this discussion she will focus on EAPs as defined by the Employee Assistance Professionals Association:

The work organization’s resource that utilizes specific core technologies to enhance employee and workplace effectiveness through prevention, identification, and resolution of personal and productivity issues.1

The core technologies include

- consultation, training, and assistance to the work organization leadership to help improve the work environment and job performance;

- active promotion of employee assistance services;

- problem identification and assessment services for individuals;

- use of constructive confrontation, motivation, and short-term intervention;

- referral of clients for diagnosis, treatment, and assistance, as well as case monitoring and follow-up services;

- effective relationships with community service providers; and

- identification of the effects of employee assistance on a variety of outcomes (Roman and Blum, 1985).

The Employee Assistance Professionals Association further explains that EAPs serve two sets of clients: the work organization and the employees. EAPs assist work organizations in addressing productivity issues, and EAPs assist employees in identifying and solving a range of personal and other issues that could affect performance. Merrick emphasized that the two sets of clients are an important feature of EAPs (Employee Assistance Professionals Association, 2011).

When EAPs began emerging decades ago, they were primarily occupational alcohol programs. However, contemporary EAPs address a wide range of issues, including substance use, mental health, family and relationship issues, stress, and other problems. She noted that the broad-brush structure of contemporary EAPs creates the potential to depathologize many of the issues EAPs address. By removing or mitigating the stigma, the barrier to getting employees to use the EAPs can be lessened.

Merrick noted that there are three EAP models—internal, external, and hybrid. The original EAP model was internal with EAP personnel as employees of the same enterprise as the employees being assisted. This

____________

1Available at http://www.eapassn.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=521.

model is now less common. Currently, the most common arrangement is to contract out the services to an external EAP services provider. Organizations with external services typically do not have people based at the worksite. Instead there tends to be a network model similar to a health plan with providers who would see employees in their private office locations. There are some hybrid models that combine some external services with internal. Regardless of the model, a consistent aspect of EAPs is there is no co-pay for using the services.

EAPs and Workforce Resilience

A resilient workforce must have the tools it needs to cope successfully with stress. Merrick noted that EAP services help employees maximize resilience but also help management support its workforce. EAP services that build resilience for individual employees include short-term counseling, referrals for additional treatment, specialized consultation and resource advice, and job performance referrals. These services often are available to family members as well. EAP services also include services that help develop resilience at the leadership level such as consultation to supervisors, coaching, dealing with problem employees, and developing or implementing workplace policies. Additionally, training employees and managers in stress management, supervisory skills, and interpersonal skills are EAP services that can build workforce resilience. Merrick suggested that EAPs can help build resilience by focusing on prevention and intervention through identifying and treating problems early.

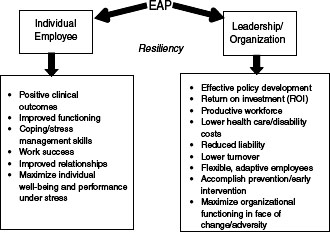

Figure 6-1 shows the two levels of EAP intervention, individual/ employee and leadership/organization, and lists some of the expected outcomes. These outcomes are primary EAP goals, and Merrick suggested that they are all resilience related. In considering the overlap between resilience, EAPs, and wellness programs, Merrick noted that coordinating them can be organizationally complex. She suggested that DHS should think about how these programs integrate or interface with one another, if there are redundancies, and if they support one another’s efforts.

FIGURE 6-1 Intervention level and outcomes.

SOURCE: Merrick, 2011.

Evidence Base for EAPs

Merrick noted that there is a substantial body of research on EAPs including work on client satisfaction, use rates, and returns on investment. Additionally, there are numerous studies on clinical and work outcomes, as well as studies of more specific interventions within EAP. She added that there are some notable limitations in the body of literature, however. One significant limitation is the frequent lack of appropriate control or comparison groups, as well as the inadequate use of statistical methods that can help address selection bias. She noted that when conducting studies in real-world situations, it is often not feasible to carry out randomized clinical trials. Another limitation of the literature is that much of it is based on individual case studies. Additionally, many of the older studies are based on EAP models that are no longer the dominant model and make comparisons to current EAP models difficult.

Merrick quoted the Employee Assistance Research Foundation’s commentary on the evidence base:

Although some studies suggest EAPs are generally effective, the EAP evidence base leaves many questions

unanswered. In part this is due to common methodological limitations; for example, the literature is dominated by single case studies and by program evaluations that do not always meet rigorous scientific standards. Although there has been an impressive accumulation of program evaluations undertaken by employers (and their employee assistance providers or consultants), most of these evaluations have been considered proprietary and not widely disseminated or published in scholarly journals. (Employee Assistance Research Foundation, n.d.)

With these limitations in mind, Merrick summarized the evidence base. The studies have typically found improved clinical and work outcomes, including in the areas of absenteeism, job performance, presenteeism, depression, and other problematic symptoms such as substance use. Satisfaction or experience of care is consistently positive. The reported satisfaction level of employees who used the EPA is often over 90 percent.

Merrick noted that a large number of studies report a positive return on investment. The return on investment is the extent to which savings from the effects of this program exceed its costs. The return on investment includes savings from health care costs, disability claims, and absenteeism, which are similar to the costs mentioned in relation to wellness programs.

However, there are some complexities in understanding cost implications of EAPs. At least one study has found program use may increase in the short term consistent with facilitation of needed services.

Utilization Challenges

Although there are indications that EAPs are effective, if people do not take advantage of them then their effects will be limited. This is a challenge with all of behavioral health care, and EAPs are no exception. Reported EAP use varies, and part of the variation is caused by different ways of calculating use. The question becomes how do you facilitate the use of EAPs? Based on the literature, Merrick suggested several key facilitators:

- Positive perceptions of EAP accessibility, confidentiality, and efficacy

- Alignment with organizational culture

- High levels of program promotion, visibility, and EAP worksite activities

- Awareness and positive promotion by supervisors and managers

- Communication through multiple and inclusive approaches

All of these facilitators are associated with either greater EAP use and practice, or a stated willingness to use the EAP. Merrick also mentioned some barriers to EAP use, including individual psychological barriers and social stigma. She noted that stigma is a barrier that was mentioned by several workshop speakers.

Measuring EAP Performance

Merrick noted that measuring EAP performance is critical. Owing to the diversity of EAPs it has been a major challenge in the field to arrive at a broad use of standardized measures. There has been a large movement toward adoption of performance measures in EAPs, and several frameworks have been proposed. The Employer’s Guide to Employee Assistance Programs has recommended three categories of metrics: utilization, impact assessment, and financial return (Rothermel, 2008). Another framework breaks the three metric categories into direct costs or health care value, indirect costs or human capital value, and organizational value (Attridge, 2003). A task force appointed by the Employee Assistance Professionals Association recommended at least six possible measures of utilization. These include the number of times individuals requested:

- information only,

- help with life management, and

- active EAP services such as trainings or referrals.

These are measured separately for eligible employees and covered lives.

Merrick made a couple of suggestions for developing outcome measures. First, she suggested maximizing the use of existing administrative or clinical data, and second, she suggested determining what other supplemental questionnaires or tools could be added to supplement it. Further, whenever it is possible, use standardized, validated instruments.

LEVERAGING EXISTING SERVICES AND PROGRAMS PANEL DISCUSSION

Mirabito and Merrick participated in a session where they took questions from other workshop participants. Planning committee member Scott Mugno moderated the discussion. The discussion topics included how best to integrate and coordinate services, program development within a federal agency, and how to ensure that services are tailored to the organizations’ cultures.

Connecting EAP to Resilience

Mugno opened the panel discussion by returning to the repeated theme of varied terminology. He works for FedEx, which has extensive EAP services, but he noted that most people do not make the connection between the EAP and resilience. Perhaps this connection is a very important one for employers to recognize.

Wellness Programs Within a Federal Agency

Summary panelist Brian Flynn asked how wellness programs could be translated to a government agency. Mirabito suggested that the agency should start with an audit of the current programs to determine to what extent they fit within the six pillars of effective workplace wellness. She noted the first goals should be creating a culture where resilience is valued within the organization and establishing a pervasive multilevel leadership commitment to resilience. She suggested that the next steps would be to create a signature program as an umbrella for the various programs that are currently in place, and then work on branding and message clarity. She recommended that DHS identify a component that is the most interested in wellness and put a comprehensive program in place there. Once in place, the program effectiveness should be measured. With a success as a stepping stone it will be easier to roll the program out to other parts of the organization.

Summary panelist Joseph Hurrell commented that the American Psychological Association gives away an annual award to a healthy work organization with selection criteria very similar to the six pillars Mirabito presented. The winning organizations receive a great deal of positive publicity, and he suggested that a similar competition between agencies within DHS might be possible.

Summary panelist Kevin Livingston retold a story of one of his employees who was an excellent peer-support counselor but ended up committing too much time to this role. Livingston cautioned moderation in time spent by employees as a wellness champion. If it takes away too much from their work, the program could lose the support of the leadership. Summary panelist Bryan Vila also cautioned that it creates the risk of burning out the employees.

Coordination of Programs

Katherine Brinsfield from DHS brought up the issue of coordination between programs. She asked how DHS could increase coordination and communication. Merrick suggested that DHS increase the mutual awareness of resilience-related programs and facilitate discussions about how best to integrate services. Second, when vendors are involved, it is important for the organization to be clear that integration is a priority. EAP is a very competitive business and, if coordination is a priority for the organization, it should be able to find vendors that are willing to work on it. Mirabito added that a best practice she saw in her research was a model that integrated EAP and wellness programs into the health benefit design. Structurally, most companies have found that if all of those functions are reporting to the same boss, it is easier to facilitate hand offs from one organization to another.

The Organizational Culture and EAP Services

Lisa Teems, the EAP manager at the U.S. Coast Guard, asked the panelists to comment on the issue of developing resilience programs that are relevant to the specific culture when working with outside vendors. She noted that there seems to be a natural tension between the two because DHS has a very specific culture, and EAP vendors are often just a 1-800 number. Dr. Merrick agreed that this tension can be a problem and is one reason why some employers choose to have internal EAPs. However, if the organization is working with an external EAP it is possible to overcome this tension. An external EAP should have the capacity to do essential on-site activities such as orientations and on-site trainings, and to get to know the company’s needs. In addition, there are big differences across EAPs in terms of their expertise in dealing with certain kinds of workforces. Even though they may not know DHS, they may have experience

with similar workforces. These considerations should be made during the purchasing decisions.

Mugno mentioned that FedEx has only had two EAP vendors while he has worked there, and both of them know FedEx and its culture well. It was part of the contract that they understood the company, and they learned about the company. Although the EAP is run off site through a toll-free number, it has access inside the firewall so it knows who it is talking to just by pulling up the directory. The EAP provider would understand the job, and what tasks and stresses go along with it. Access through the firewall would obviously be an issue for the government, but there are other ways to achieve this end.

Planning committee member Karen Sexton mentioned that, being in health care, she has had the privilege of working with good EAPs. Unfortunately, because EAPs started as substance abuse programs, there is still stigma with using them. In her work, there was a destigmatizing effort post–Hurricane Ike where everyone in leadership made it known publicly that they were going to the EAP for assistance. She suggested that maybe it could be mandatory for everyone to go to the EAP once a year for an assessment of their work and personal life. Merrick responded that the more voluntary the use of the EAP is, the more likely it is to foster a positive view of services. However, she understands the issue of stigma and the challenge it presents.

Attridge, M. 2003. Making the business case for employee assistance programs: Annotated bibliography of key research studies. Presented at the 24th Annual Training and Conference of the Employee Assistance Professionals Association’s North Carolina Chapter. Charlotte, NC.

Baicker, K., D. Cutler, and Z. Song. 2010. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Affairs (Millwood) 29(2):304-311.

Berry, L. L., A. M. Mirabito, and W. B. Baun. 2010. What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs? Harvard Business Review 88(12):104-112, 142.

Employee Assistance Professionals Association. 2011. Definitions of an employee assistance program (EAP) and EAP core technology. http://www.eapassn.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=521 (accessed February 17, 2012).

Employee Assistance Research Foundation. n.d. EAP research. http://www.eap-research/ (accessed February 17, 2012).

Henke, R. M., R. Z. Goetzel, J. McHugh, and F. Isaac. 2011. Recent experience in health promotion at Johnson & Johnson: Lower health spending, strong return on investment. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(3):490-499.

Merrick, E. 2011. The role of EAP programs in supporting workforce resiliency. Presented at Operational and Law Enforcement Personnel Workforce Resiliency: A workshop. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine. September 15.

Roman, P., and T. Blum. 1985. The core technology of employee assistance programs. ALMACAN 15:8-19.

Rothermel, S. 2008. Employer’s guide to employee assistance programs. National Business Group on Health. http://www.businessgrouphealth.org/pdfs/FINAL%20NBGH%20Guide%20to%20EAPs%204%2030%2008.pdf (accessed February 17, 2012).

This page is blank