Abstract: This chapter presents the objectives, scope, and context for this report and describes the approach that the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on the Mental Health Workforce for Geriatric Populations used to undertake the study. The committee’s charge was twofold: first, to determine the mental health and substance use (MH/SU) needs of the 65-and-older population and, second, to develop recommendations for ensuring a competent and sufficient workforce to meet these needs. This study was undertaken during a period characterized by considerable uncertainty regarding the future organization and financing of the U.S. health care system, dramatic change in the makeup of the older population, and great concern about the capacity of the nation’s MH/SU workforce to meet the needs of older adults. Federal responsibility for geriatric MH/SU is diffused among numerous U.S. Department of Health and Human Services agencies, and the agencies’ attention to these concerns is minimal and dwindling.

The aging of America has and will continue to have profound consequences for the nation’s economy and society for years to come. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that the number of adults age 65 and older will increase from 40.3 million to 72.1 million between 2010 and 2030 (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). During the same period, the ethnic, racial, and cultural

makeup of the older adult population will become more diverse than ever (Cummings et al., 2011; Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). The impact on the demand for and cost of health care will be unprecedented. In 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued a report, Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce, which highlighted the urgency of expanding and strengthening the geriatric health care workforce to meet the demands of our rapidly aging and changing population (IOM, 2008). The following year, because of similar concerns about geriatric mental health and substance use (MH/SU) needs, Congress mandated that the IOM undertake a complementary study focusing on the geriatric MH/SU workforce needs of the nation (U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, 2009). Thus, in response to the congressional mandate, the IOM entered into a contract with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in September 2010. The IOM Committee on the Mental Health Workforce for Geriatric Populations was appointed in early 2011 to carry out the charge. The 16-member committee included experts in geriatric psychiatry, substance use, social work, psychology, and nursing; direct care workers; and those with specialties in epidemiology, workforce development, labor economics, long-term care, health care delivery and financing, and health care disparities.1 Brief biographies of the committee members are provided in Appendix E.

The charge to the committee was essentially twofold: first, to assess the current and projected MH/SU needs of adults age 65 and older and, second, to recommend how the nation should prepare the MH/SU workforce to meet these needs (Box 1-1). The committee was also asked to address the unique needs of important subgroups in the older adult population, including individuals of diverse ethnic backgrounds, veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder, and persons living with chronic disease. The study sponsor asked the committee to define the MH/SU workforce broadly (Frank, 2011). The committee focused on the full spectrum of workers who are engaged in the diagnosis, treatment, care, and management of MH/SU conditions in older adults—ranging from personnel who may have minimal education to specialty physicians with the most advanced psychiatric and neurological training. This includes

____________

1 An additional committee member with expertise in the consumer perspective was also appointed, but had to step down from the committee due to illness.

BOX 1-1

Charge to the IOM Committee on the Mental Health Workforce

for Geriatric Populations

At the request of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) will convene an ad hoc committee to determine the mental and behavioral health care needs of the target population—the population of Americans who are over age 65 years—and then make policy and research recommendations for meeting those needs through a competent and well-trained mental health workforce, especially in light of the projected doubling of the aged population by 2030.

The committee will

• Provide a systematic and trend analysis of the current and projected mental and behavioral health care needs of the target population.

• Within the target population, consider the special needs of growing ethnic populations, of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder, and of persons with chronic disease.

• Weigh the impact of improved diagnostic techniques, of addressing mental health issues as part of effective chronic disease management, and of the implementation of the federal mental health parity law on meeting the mental health needs of the target population.

When making recommendations, the committee will consider forces that shape the health care workforce, such as education, training, modes of practice, and the financing of public and private programs.

• MH/SU specialists such as general psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, psychiatric nurses, and substance use counselors who may provide services to patients or clients of any age;

• primary care providers, such as general internists, family medicine practitioners, advanced practice registered nurses, and physician assistants who may provide services to patients of any age (but may have daily contact with older adults who have MH/SU conditions);

• primary care providers with specialized training in the care of older adults, such as geriatricians and geriatric nurses (excludes MH/SU specialists);

• MH/SU providers with specialized training in the care of older adults, such as geriatric psychiatrists, gerontological nurses, geropsychologists, and gerontological social workers;

• direct care workers who, with minimal training, are employed to provide supportive services either in facilities or in the home;

• peer support providers who, with special training, teach peers the skills and behaviors to self-manage their mental illness; and

• informal caregivers such as family members, friends, and volunteer community members with the potential to identify and support older adults who may need MH/SU services.

In its early deliberations, the committee worked on refining its charge and workplan for the study. During the first committee meeting, the study sponsor made five suggestions that helped the committee focus its work: (1) concentrate on the MH/SU conditions that are most prevalent among older adults and for which there are sufficient data for study (Box 1-2); (2) exclude the principal diagnoses of cognitive impairment (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias), intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder, but include the behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia; (3) do not explore the effectiveness of individual therapeutic interventions (e.g., prescription medications, specific approaches to psychotherapy); (4) exclude tobacco use as a substance use condition; and (5) exclude workforce issues related to caregivers’ needs. The sponsor also recommended that the committee limit its inquiry into diagnostic techniques to the question of how the workforce can most effectively identify older adults who need MH/SU services.

BOX 1-2

Geriatric Mental Health and Substance Use Conditions

Addressed in This Report

Older adults with the following conditions are the focus of this report. See Chapter 2 for definitions of each condition and related epidemiological data and analysis.

|

DSM-IV-TR Mental Disorders • Adjustment disorder • Anxiety disorders (including posttraumatic stress disorder) • Bipolar disorder • Depressive disorders • Personality disorders • Schizophrenia • Substance-related disorders (including alcohol dependence and abuse, drug dependence and abuse) |

Other Conditions • Anxiety symptoms • At-risk drinking or drug use • Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia • Complicated grief • Fear of falling • Hoarding • Minor depression (depressive symptoms) • Severe domestic squalor • Severe self-neglect • Suicidal ideation, plans, or attempts |

(e.g., Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias), intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder, but include the behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia; (3) do not explore the effectiveness of individual therapeutic interventions (e.g., prescription medications, specific approaches to psychotherapy); (4) exclude tobacco use as a substance use condition; and (5) exclude workforce issues related to caregivers’ needs. The sponsor also recommended that the committee limit its inquiry into diagnostic techniques to the question of how the workforce can most effectively identify older adults who need MH/SU services.

The committee deliberated during four in-person meetings and numerous teleconferences between March 2011 and April 2012. In June 2011, the committee held a public workshop to learn the perspectives of selected stakeholders, including consumers, families, and caregivers; providers who care for older adults in various settings; researchers who have studied the effectiveness of different models of care; and policy makers. Appendix B contains the workshop agenda.

As the subsequent chapters will make clear, data are very limited describing older adults with MH/SU conditions, the workforce that serves them, or the private and public programs that support them. The study committee and staff consulted with many representatives of public-and private-sector organizations to obtain information about relevant programs and policies. Staff from HHS agencies (Administration on Aging, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and others) and the Veterans Health Administration offered critical insights and program data. The professional organizations listed in Box 1-3 provided information on training and education, requirements for program accreditation, licensing and certification, and trends in the size and makeup of the workforce.

Terminology

This report uses the term “geriatric MH/SU workforce” to refer to the full range of personnel providing services to older adults with MH/SU conditions. The term “older adult” refers to individuals age 65 and older.

Many terms and labels are used to describe mental health conditions and problems related to abuse or misuse of substances. This report uses the term “mental health condition” to describe mental disorders defined

BOX 1-3

Nongovernmental Organizations That Provided Workforce

Information to the IOM Committee

• American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry

• American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy

• American Association of Physician Assistants

• American Counseling Association

• American Geriatrics Society

• American Mental Health Counselors Association

• American Occupational Therapy Association

• American Psychiatric Nurses Association

• American Psychological Association

• ARCH National Respite Network

• Council for Social Work Education

• Direct Care Alliance

• National Alliance for Caregiving

• National Association of Social Workers

in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR)2 as well as the range of symptoms and syndromes that result in significant emotional distress, functional disability, and reduced quality of life in older adults. The term “substance use conditions” refers to abuse, misuse, or dependence on alcohol and drugs (both illicit drugs and prescription and nonprescription medications).

A Health Care System in Transition

As this report goes to press, the degree of uncertainty about the future of the U.S. health care delivery system is unprecedented. The nation awaits the outcome of a U.S. Supreme Court decision regarding the constitutionality of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.3 The outcome has substantial implications for older adults with MH/SU conditions because the Act contains numerous provisions related to the

![]()

2 DSM, or DSM-IV-TR, refers to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. During the course of this study, the Fourth Edition-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) was in use. A fifth edition is expected in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2012).

3 Public Law 111-148.

health care workforce, the delivery and integration of MH/SU services, and the organization and financing of Medicare and Medicaid MH/SU services. In addition, as Box 1-4 describes, recent legislation mandating parity in insurance coverage of physical and mental health conditions will be implemented during the next few years.

The backdrop for these events is a dramatic shift in the age makeup of the U.S. population. Numerous expert reports have stressed the urgency of preparing the nation’s health care workforce for the “silver tsunami” of the aging baby boomer population (IOM, 1978, 2008). Along with the sheer growth in numbers of Medicare beneficiaries will be a corresponding rise in demand for health care services. Many of the older adults seeking physical health care services in primary care settings, hospitals, and elsewhere will have coexisting MH/SU conditions. Considerable evidence shows that older adults with MH/SU conditions are among the most costly Medicare beneficiaries (Alecxih et al., 2010; Cummings and Kropf, 2011; MedPAC, 2011). Older adults have complex and multiple health care problems. When these medical conditions are accompanied by a mental health or substance use diagnosis, the older patient is likely to use more costly services and suffer poorer outcomes. If the nation is to confront the growing burden of Medicare costs, it must develop ways to maximize the productive capacity of the geriatric MH/SU workforce. Many reports have also described the inadequate supply of MH/SU personnel (Hogan, 2003; Hoge et al., 2007; IOM, 2006; Jeste et al., 1999). The U.S. health care delivery system has always focused more on physical health than mental health (IOM, 2006). This stems from numerous factors, including long-held societal biases against MH/SU conditions, limitations on health coverage of MH/SU conditions, federal statutes that require states to assume primary responsibility for adults under age 65 with serious mental illness, and the widespread carve-out of MH/SU coverage and service delivery into systems separate from the rest of health care.

Perhaps, as a consequence, MH/SU health care delivery is inadequate and of poor quality for most older adults. Many MH/SU conditions are neither detected nor diagnosed properly in older adults. Because MH/SU problems rarely occur apart from physical health problems, care coordination is integral to good health outcomes (Lin et al., 2003, 2011; Noel et al., 2004). Evidence-based, effective treatments and models exist for coordinating MH/SU care. Moreover, there is growing evidence suggesting that effective identification and treatment of MH/SU conditions may be central to reducing the costs and improving the effectiveness of the Medicare program (Unützer et al., 2008).

BOX 1-4

Parity for Coverage of Geriatric Mental Health/Substance Use

(MH/SU) Services

In 2008, two landmark bills mandating parity in health insurance coverage of MH/SU services became law: (1) the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-275) and (2) the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-343). The following describes both mandates and briefly considers the possible implications for the geriatric MH/SU workforce:

• Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA). Since the creation of the Medicare program, the Medicare coinsurance rate for outpatient mental health services has been much higher than the rate for most other outpatient health care services (i.e., 50 percent vs. 20 percent). MIPPA equalizes the outpatient Medicare coinsurance rates, thus creating “parity” in the coverage of mental health and physical health care. The reduction in the coinsurance rate from 50 to 20 percent is being phased in over a 5-year period starting in 2010.

• Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. This law mandated parity in the coverage of physical and MH/SU conditions by employer-sponsored group health plans with more than 50 insured employees. The health plans are not required to provide MH/SU benefits but, if they do, the benefits must be no more

Changing Face of the Older Population

The older adult age cohort is not only growing rapidly, but the age distribution within the cohort is changing, as is the racial and ethnic makeup of the population (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). Census projections indicate that, from 2003 to 2030, the proportion of older adults who are white (non-Hispanic) will decline from 83 percent to 72 percent (Table 1-1).

The increasing proportion of older adults who are racial/ethnic minorities will demand a workforce that is prepared to work with diverse populations. In particular, the rapid growth of Hispanic and Asian populations will necessitate increased linguistic competence from the workforce. Black, Hispanic, and Asian are deceptively simple categorizations for the many nationalities, languages, and subcultures represented in these groups. Preparing a culturally and linguistically competent workforce

restrictive then the plan’s medical and surgical benefits. Thus the deductibles, copays, coinsurance, out-of-pocket maximums, and treatment limitations (including day or visit limits and medical management tools) for MH/SU and physical health conditions must be the same.

Workforce Implications

Little evidence suggests that either parity mandate will have much impact on the geriatric MH/SU workforce. Parity could potentially increase demand for the services of MH/SU providers. However, it is unlikely the increased demand will be large enough to motivate more providers to provide geriatric MH/SU services. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office has predicted that parity will have minimal impact on costs.

Most importantly, parity does not affect what MH/SU services are covered by Medicare or which providers can be reimbursed for providing MH/SU care to older adults. As a result, even after full phasein of parity, the evidence-based innovations in MH/SU care delivery (described in Chapter 4) will continue to be unreimbursable under the Medicare program.

____________

aThe Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) extends the mandate to other types of private health insurance plans.

SOURCES: Congressional Budget Office, 2008; Garfield et al., 2011; MedPAC, 2010; Sarata, 2011.

that reflects the diversity of the wider population will be an important challenge for the coming decades.

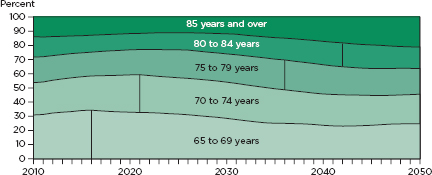

Figure 1-1 shows the age distribution of the projected older population through 2050. Currently, persons ages 65 to 69 make up the largest proportion of the older population. However, as the oldest of the baby boomers age, the age distribution will shift, with an increasing percentage of the older population being over 80 years old. Because the “oldest-old” typically require more frequent and more intense care than the “young-old,” the changing age distribution of the older population has many implications for the health care workforce.

The Health Care Workforce

This examination of the MH/SU workforce for geriatric populations occurs within the context of the nation’s health care workforce at large, the

| Race/Ethnicity |

Percentage of Population Ages 65 |

|

|

2003 |

2030 |

|

| Non-Hispanic white |

83 |

72 |

| Black |

8 |

10 |

| Hispanic |

6 |

11 |

| Asian |

3 |

5 |

NOTE: Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

SOURCE: Drayer et al., 2005.

workforce that specializes in the care of older adults, and the workforce trained broadly to provide services to individuals with MH/SU conditions. There are numerous and substantive concerns about the workforce as a whole, as well as its specialty sectors. Understanding these concerns is critical to grasping the enormous obstacles to building a strong workforce that can meet the MH/SU needs of the growing geriatric population.

FIGURE 1-1

Distribution of the projected older population by age for the United States, 2010-2050.

NOTE: The vertical line indicates the year that each age group is the largest proportion of the older population.

SOURCE: Vincent and Velkoff, 2010.

Concerns About the Overall Health Care Workforce

In Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, the IOM called for major changes in health care workforce development, training, and education (IOM, 2001). It highlighted, among other problems, the critical challenges in recruitment and retention, which have been most visible in the field of nursing and the inadequate preparation of the workforce as a whole to function in interdisciplinary teams and to implement evidence-based practices. A subsequent IOM report, Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality, added to this list of concerns the lack of preparedness among the workforce to address shifts in the nation’s patient population, analyze and address problems in health care quality, and use informatics to support the provision and quality of care (IOM, 2003). A myriad of other issues have been identified by other experts, including the limited attention given to preparing and supporting the direct care, largely nondegreed workforce (Hewitt et al., 2008) or the self-care and peer support roles of individuals and family members (Brown and Wituk, 2010; Mowbray et al., 1997).

Improvements in health care workforce development have been impeded by a range of factors, including conservative professional hierarchies that govern health professions education and facilitate a very gradual pace of reform; a dense and inconsistent patchwork of laws, regulations, agencies, and accreditation processes that are slow to adapt and change; continuing education approaches that have minimal effect on clinical practice or health care outcomes; and the absence of methods for ensuring the ongoing competence of practitioners (IOM, 2001).

Concerns About the Workforce for Geriatric Populations

The state of the nation’s workforce that is specifically trained to care for older adults was captured recently and comprehensively in Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce (IOM, 2008). As Chapter 3 will describe, the available statistics are sobering. They document how few individuals choose to specialize in geriatrics in any sector of health care, and the frequency with which such individuals decide to let their credentials in geriatric specialties lapse. Among the geriatric specialists that remain in this field, there is marked maldistribution, with few working in rural areas even though older adults are overrepresented in rural areas and are less healthy than their urban counterparts.

For members of the general workforce, professional education provides little training related to the assessment and treatment of older adults and little exposure to geriatric populations. Whatever is provided tends to occur late in the sequence of educational experiences, minimizing its potential to influence interest in specialization. Factors cited as impediments

to increasing training regarding geriatric care include the lack of faculty trained in geriatrics, the lack of funds, competition for time in program curricula, the stigma associated with older adults and their care, and financial disincentives to geriatric practice.

Concerns About the General MH/SU Workforce

Challenges confronting the MH/SU workforce were highlighted in detail in a number of reports released over the past decade, including Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions (IOM, 2006); Strengthening Professional Identity: Challenges of the Addiction Treatment Workforce (Whittier, 2006); and An Action Plan for Behavioral Health Workforce Development (Hoge et al., 2007). These reports captured the enormous complexity of the behavioral health workforce with its numerous professions, variation in educational approaches, and varied workforce type, including professionals, direct care workers, persons in recovery, and family members. Data on this workforce have not been collected routinely or in a uniform manner, making it difficult to understand its composition and relevant trends. However, the information available highlighted the striking lack of racial and cultural diversity, particularly at the professional level, and the serious workforce shortages. The latter have been acute, especially in rural and frontier areas of the country and for the field of addictions.

Training in the screening, assessment, and treatment of substance use disorders is typically minimal in all but addiction-specific professional programs despite the prevalence of substance use conditions among those receiving mental health care (see Appendix C). Similarly, there has been a noted dearth of practitioners trained in meeting not only the needs of older adults, but children and youth as well. Many professionals have struggled to understand and incorporate recovery-oriented approaches to care, but the behavioral health disciplines, in general, have had difficulty blending their drive to professionalize their discipline with the growing focus on recovery and peer support. Furthermore, it has been a challenge educating and engaging the MH/SU workforce in evidence-based practices, such as the use of medications to treat addictions. Innovative efforts to address the myriad of workforce problems in behavioral health have tended to be short-lived with little evaluation of their impact or dissemination nationally.

FEDERAL INFLUENCE ON THE GERIATRIC MH/SU WORKFORCE

Many federal policies influence the makeup, competence, and capacity of the health care workforce to deliver MH/SU services to older adults.

Many federal agencies, particularly within HHS, have the authority to catalyze activities to strengthen the geriatric MH/SU workforce and to improve the quality of services they provide. Yet federal responsibility appears to be diffused across various agencies, bureaus, and departments. No one entity within HHS is taking the lead. As Table 1-2 suggests, HHS agencies’ attention to the older adult population with geriatric MH/SU conditions has been minimal and is clearly declining.

Chapter Objectives

This introductory chapter has described the background, charge to the committee, scope, methods, and context for this report.

Chapter 2, “Assessing the Service Needs of Older Adults with Mental Health and Substance Use Conditions,” presents prevalence and use data and considers the impact of population trends, particularly the aging of the baby boomer cohort and growing population diversity, on the makeup of the older population and future needs for MH/SU services.

Chapter 3, “The Geriatric Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce,” describes the spectrum of personnel who serve older adults with MH/SU conditions and assesses the capacity and competence of the workforce to meet the needs of this population.

Chapter 4, “Workforce Implications of Models of Care for Older Adults with Mental Health and Substance Use Conditions,” describes nine evidence-based MH/SU interventions for older adults, the implications of the models for developing the workforce, and the barriers to implementation.

Chapter 5, “In Whose Hands? Recommendations for Strengthening the Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce for Older Americans,” presents the committee’s findings and recommendations.

| Key Focus/Agency | Emphasis on Mental Health and Substance Abuse (MH/SU) Services and Workforces |

|

FINANCING |

|

|

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) |

|

|

—Medicare and Medicaid programs |

• Medicare—40 million adults age 65+ were Medicare beneficiaries in 2011. Medicare payment rules are the principal driver of (1) which providers and other types of personnel can be reimbursed for providing MH/SU services to older adults, (2) how the geriatric MH/SU workforce is organized to provide services, and (3) the types of services that are provided. ° Supports quality-improvement organizations (QIOs), private organizations charged with improving the quality of health care for Medicare beneficiaries. • Medicaid—nearly 10 percent of Medicare beneficiaries over age 64 have dual Medicaid and Medicare coverage. A significant proportion has serious mental illness (SMI). Medicaid is the principal payer of nursing home care for older adults with MH/SU conditions. Thus, the Medicaid program ° oversees the implementation the Preadmission Screening and Resident Review Program (PASRR), which requires MH screening and treatment follow-up for nursing home residents. ° oversees the implementation of the Minimum Data Set (MDS), a mandatory data collection and screening instrument for assessing nursing home patients’ physical and mental health status. • Medicaid also administers two programs that serve older adults with MH/SU conditions: ° Home- and community-based waivers for individuals who would otherwise require care |

|

in a nursing home or other institutional setting (about 30 percent of all long-term care Medicaid spending). ° The “Money Follows the Person” rebalancing demonstration program, which helps state Medicaid programs support the use of home- and community-based services in lieu of nursing homes or other institutional services (including for older adults with SMI who are transitioning out of institutions into the community). • The CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) sponsors several largescale initiatives to develop and assess ways to improve the quality, effectiveness, and efficiency of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. These include Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Bundled Payments for Care Improvement, the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, the Health Care Innovation Challenge, State Demonstrations to Integrate Care for Dual Eligibles, the Medicaid Emergency Psychiatric Demonstration, and others. |

|

RESEARCH |

|

|

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) |

|

|

—Center for Primary Care, Prevention, and Clinical Partnerships |

No specific focus on geriatric MH/SU. • Spearheading the creation of an Academy for Integrating Mental Health and Primary Care to serve as a national coordinating center and clearinghouse for the collection, analysis, synthesis, and dissemination of research on integrating MH/SU services in primary care. |

| —Effective Health Care Program |

No specific focus on geriatric MH/SU. • Funds clinical effectiveness research on a broad range of topics related to the needs of the Medicare, Medicaid, and State Children’s Health Insurance Programs. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) |

Administers or supports several programs and research related to geriatric MH/SU. • The Healthy Aging Research Network sponsors, translates, and disseminates research on programs and policies to facilitate healthy aging including the Program to Encourage Active and Rewarding Lives for Seniors (PEARLS), one of the first studies to demonstrate the feasibility of collaborating with community service organizations to identify and effectively treat depressed, homebound older adults primarily with counseling rather than prescription drugs. • The National Center for Health Statistics, a CDC division, conducts numerous population-based surveys that collect epidemiologic and use data related to geriatric MH/SU (including the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, the National Health Interview Survey, and others). |

|

National Institutes of Health (NIH) |

|

|

—National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH) |

|

|

° NIMH Geriatrics Research Branch |

Diminishing focus on research related to effective delivery of geriatric MH/SU services. Access to new funding for the Advanced Centers for Interventions and Services Research has been eliminated. • Supports research, training, and resource development related to the etiology and pathophysiology of late-life mental disorders. • Has also funded research on telehealth, online curricula development, and collaborative care. |

|

° NIMH Services Research and Clinical Epidemiology |

• Supports two programs related to service delivery in MH/SU although neither program focuses on older adults. The Primary Care Research Program supports studies that examine what types of MH/SU care can be integrated into the primary care setting. The Systems Research Program supports studies on organization and coordination of MH/SU care settings, including schools, community organizations, and criminal justice facilities. |

| —National Institute on Aging (NIA) |

• Supports research on Alzheimer’s disease and other diseases that cause dementia. • Supports epidemiological research on depression and other mental health conditions as well as research on nursing home populations. |

| —National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)a | Funds research on alcohol abuse, alcoholism, and health effects of alcohol with some focus on adults age 60 and older. |

| — National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)a | Principal focus is on biomedical neuroscience, but funds some extramural research on epidemiology, services, and prevention, including research on drug abuse in the older adult population. |

|

RESOURCES AND SERVICES |

|

|

Administration on Aging (AoA) |

Provides nonmedical services to help older adults maintain health and independence and supports research on related topics. • Administers the National Aging Network, a national service infrastructure that funds state-level organizations that provide home- and community-based services (including the Aging and Disability Resource Center and the National Family Caregiver Support Program). • Has supported research and dissemination of evidence on several community-based, MH/SU screening and interventions for older adults, including Healthy IDEAS, PEARLS, HomeMEDS, ElderVention, and the Brief Intervention and Treatment for Elders. |

| • Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) |

| —Bureau of Health Professions |

MH/SU content is not required in geriatric training programs. • Administers several grant programs open to geriatric MH/SU professionals, including ° Comprehensive Geriatric Education Program ° Geriatric Academic Career Awards ° Geriatric Education Center Program ° Geriatric Training Program for Physicians, Dentists, and Behavioral and Mental Health Professions • From 2007 to 2010, the above programs provided training and education in mental health (88 percent) and substance use (22 percent) to 93,616 individuals. Participants represented a wide range of disciplines, including nursing (24 percent), medicine (15 percent), social work (12 percent), and others (49 percent). |

| —National Health Service Corps |

No emphasis on geriatric MH/SU workforce. • Provides loan repayment and scholarships to providers in exchange for service commitment in underserved areas (primarily to a nonelderly population). • More than 3,000 MH specialists (psychiatrists, psychologists, licensed clinical social workers, psychiatric nurse specialists, marriage and family therapists, and licensed professional counselors) have participated in the corps. |

| —Bureau of Primary Health Care |

No emphasis on geriatric MH/SU workforce. • Provides financial support to community health centers providing primary care to underserved persons; patient population is primarily nonelderly (less than 7 percent is age 65 and older). • Participating health centers must provide or arrange for MH and SU services; about two-thirds of the centers provide mental health services onsite. |

| Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) |

Once a priority population, older adults are no longer a focus of SAMHSA activities. Starting in 2013, the agency will not fund any grant programs dedicated specifically to geriatric MH/SU. • Notable programs related to older adults: ° Older Adults Targeted Capacity Expansion (TCE) Grants—a service grant program that directed resources to older adults from 2002 to 2011; 29 programs received grants. Included a Technical Assistance Center. ° Enhancing Older Adult Behavioral Health currently funds five of the former TCE grantees. This 18-month initiative focuses on suicide prevention and prescription drug misuse/abuse among older adults. |

a NIH is assessing a possible merger of NIDA and NIAAA into a combined Substance Abuse/Addictions Institute (as recommended by the NIH Scientific Management Review Board in 2010).

SOURCES: AoA, 2011a,b,c; Ciechanowski et al., 2004; Davis et al., 2012; HRSA Bureau of Health Professions, 2011; Medicaid.gov, 2012; Miller, 2011; NIAAA, 2010, 2011; NIDA, 2011; NIH, 2010, 2011; NIMH, 2011a,b,c; SAMHSA, 2006, 2011a,b,c; SCAN Foundation, 2011.

Alecxih, L., S. Shen, I. Chan, D. Taylor, and J. Drabek. 2010. Individuals living in the community with chronic conditions and functional limitations: A closer look. http://www.lewin.com/content/publications/ChartBookChronicConditions.pdf (accessed January 19, 2012).

American Psychiatric Association. 2012. DSM-IV-TR. http://www.dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx (accessed June 1, 2012).

AoA (Administration on Aging). 2011a. About AoA. http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/About/index.aspx (accessed November 13, 2011).

———. 2011b. Behavioral health. http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/AoA_Programs/HPW/Behavioral/index.aspx (accessed November 15, 2011).

———. 2011c. National aging network. http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/AoA_Programs/OAA/Aging_Network/Index.aspx (accessed April 14, 2011).

Brown, L. D., and S. Wituk, eds. 2010. Mental health self-help: Consumer and family initiatives. New York: Springer.

Ciechanowski, P., E. Wagner, K. Schmaling, S. Schwartz, B. Williams, P. Diehr, J. Kulzer, S. Gray, C. Collier, and J. LoGerfo. 2004. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291(13):1569-1577.

Congressional Budget Office. 2008. Cost estimate H.R. 6331: Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008, enacted as P.L. 110-275 on July 15, 2008.

Cummings, M. R., V. A. Hernandez, M. Rockeymoore, M. M. Shepard, and K. Sager. 2011. The Latino age wave: What changing ethnic demographics mean for the future of aging in the United States. http://www.atlanticphilanthropies.org/sites/default/files/uploads/HIP_LatinoAgeWave_FullReport_Web.pdf (accessed September 6, 2011).

Cummings, S. M., and N. P. Kropf. 2011. Aging with a severe mental illness: Challenges and treatments. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 54(2):175-188.

Davis, P. A., C. Binder, J. Hahn, P. C. Morgan, J. Mulvey, and S. R. Talaga. 2012. CRS report: Medicare primer (accessed January 27, 2012).

Drayer, R. A., B. H. Mulsant, E. J. Lenze, B. L. Rollman, M. A. Dew, K. Kelleher, J. F. Karp, A. Begley, H. C. Schulberg, and C. F. Reynolds. 2005. Somatic symptoms of depression in elderly patients with medical comorbidities. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 20(10):973-982.

Frank, R. 2011. Testimony to the IOM Committee on the Mental Health Workforce for Geriatric Populations. Washington, DC. March 8.

Garfield, R. L., S. H. Zuvekas, J. R. Lave, and J. M. Donohue. 2011. The impact of national health care reform on adults with severe mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 168(5):486-494.

Hewitt, A., S. Larson, S. Edelstein, D. Seavey, M. Hoge, and J. Morris. 2008. A synthesis of direct service workforce demographics and challenges across intellectual/developmental disabilities, aging, physical disabilities, and behavioral health. Falls Church, VA: The Lewin Group.

Hogan, M. F. 2003. The President’s New Freedom Commission: Recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatric Services 54(11):1467-1474.

Hoge, M. A., J. A. Morris, A. S. Daniels, G. W. Stuart, L. Y. Huey, N. Adams, and Annapolis Coalition on the Behavioral Health Workforce. 2007. An action plan for behavioral health workforce development: Executive summary. Washington, DC: SAMHSA.

HRSA Bureau of Health Professions. 2011. Title VI and Title VIII geriatrics program data on the geriatrics mental and behavioral health and substance abuse workforce. December (unpublished).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1978. Aging and medical education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

———. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

———. 2003. Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2006. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2008. Retooling for an aging America: Building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jeste, D. V., G. S. Alexopoulos, S. J. Bartels, J. L. Cummings, J. J. Gallo, G. L. Gottlieb, M. C. Halpain, B. W. Palmer, T. L. Patterson, C. F. Reynolds, and B. D. Lebowitz. 1999. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health—research agenda for the next 2 decades. Archives of General Psychiatry 56(9):848-853.

Lin, E. H. B., W. Katon, M. Von Korff, L. Q. Tang, J. W. Williams, K. Kroenke, E. Hunkeler, L. Harpole, M. Hegel, P. Arean, M. Hoffing, R. Della Penna, C. Langston, J. Unützer, and IMPACT Investigators. 2003. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis—a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290(18):2428-2434.

Lin, W.-C., J. Zhang, G. Y. Leung, and R. E. Clark. 2011. Chronic physical conditions in older adults with mental illness and/or substance use disorders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59(10):1913-1921. Medicaid.gov. 2012. Money follows the person (MFP). http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Long-Term-Services-and-Support/Balancing/Money-Follows-the-Person.html (accessed April 11, 2012).

MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). 2010. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

———. 2011. Coordinating care for dual-eligible beneficiaries. Washington, DC: MedPAC. Miller, B. 2011. The AHRQ academy for integrating mental health and primary care. http://prezi.com/pdwleusvlceo/the-ahrq-academy-for-integrating-mental-health-and-primary-care/ (accessed November 13, 2011).

Mowbray, C. T., D. P. Moxley, C. A. Jasper, and L. L. Howell, eds. 1997. Consumers as providers in psychiatric rehabilitation. Columbia, MD: International Association for Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services.

NIAAA (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism). 2010. Scientific management review board vote on merger. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/Fall2010/article05.htm (accessed November 13, 2011).

———. 2011. Fy 2012 congressional budget justification. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services.

NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse). 2011. Fiscal year 2012 budget information: Congressional justification for National Institute on Drug Abuse. http://drugabuse.gov/Funding/Budget12.html (accessed November 13, 2011).

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2010. Scientific review board: Report on substance use, abuse and addiction research at NIH. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services.

———. 2011. NIH budget request FY2012. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services.

NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health). 2011a. Geriatrics Research Branch. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/datr/geriatrics-research-branch/index.shtml (accessed November 13, 2011).

———. 2011b. Primary Care Research Program. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/dsir/services-research-and-epidemiology-branch/primary-care-research-program.shtml (accessed November 13, 2011).

———. 2011c. Systems Research Program. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/organization/dsir/services-research-and-epidemiology-branch/systems-research-program.shtml (accessed November 13, 2011).

Noel, P. H., J. W. Williams, J. Unützer, J. Worchel, S. Lee, J. Cornell, W. Katon, and L. H. Harpole. 2004. Depression and comorbid illness in elderly primary care patients: Impact on multiple domains of health status and well-being. Annals of Family Medicine 2(6):555-562.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2006. Strategic plan: FY 2006-FY 2011. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA.

———. 2011a. FY 2011 grant request for application (RFA): Grants to enhance older adult behavioral health services (short title: Older adult TCE). http://www.samhsa.gov/grants/2011/sm_11_009.aspx (accessed November 13, 2011).

———. 2011b. Leading change: A plan for SAMHSA’s role and actions 2011-2014. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA.

———. 2011c. Request for applications (RFA) No. Sm-11-009. http://www.samhsa.gov/grants/2011/sm_11_009.aspx (accessed November 13, 2011).

Sarata, A. K. 2011. Mental health parity and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

SCAN Foundation. 2011. Long-term care fundamentals. What is a Medicaid waiver? Technical Brief Series No. 8. http://www.thescanfoundation.org/sites/scan.lmp03.lucidus.net/files/LTC_Fundamental_8.pdf (accessed September 12, 2011).

Unützer, J., W. J. Katon, M.-Y. Fan, M. C. Schoenbaum, E. H. B. Lin, R. D. DellaPenna, and D. Powers. 2008. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. American Journal of Managed Care 14:95-100.

U.S. Congress, House of Representatives. 2009. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and related agencies appropriations bill, 2010. Report of the Committee on Appropriations together with minority views (to accompany H.R. 3293). Report 111-220.

Vincent, G. K., and V. A. Velkoff. 2010. The next four decades: The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Current Population Reports, pp. 25-1138. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Whittier, M. 2006. Strengthening professional identity: Challenges of the addictions treatment workforce. A framework for discussion. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA.