Successful partnerships are typically dedicated to achieving common goals, that is, with all members of a partnership working toward the same end. However, agreeing on a common goal does not necessarily mean that everyone expects to benefit from that goal in the same way. Different entities have different expectations, or hopes, for what they will gain. Reaching a shared understanding of those different expectations is a first step toward finding the common ground necessary for collaboration. As Diane Finegood said, “I think we need to understand each other’s paradigms and goals before we can embark on really serious cross-sector collaboration.” So what are those paradigms and goals? What do entities from industry, government, academia, and NGO sectors in food and nutrition expect, or hope, to gain by collaborating with each other? In other words, why partner?

This chapter summarizes the discussion and presentations that addressed the “why” of partnering. It includes results from the pre-workshop survey on “deeply held beliefs” around public–private partnerships and report-back results from the first breakout session on sector goals for multisectoral collaboration. While many participants from each sector noted the value of partnerships in food and nutrition from a public health perspective, their reasons for pursuing partnership vary. Yet, there are some important commonalities, such as the desire for more data and knowledge, where collaboration can and should be sought.

However, with benefits come risks. Most partnerships aimed at producing meaningful change involve some degree of risk taking. Also included in this chapter is a summary of the extensive discussion that took place on the

risks of public–private partnership in food and nutrition research, with a focus on integrity and public trust. The chapter concludes with a summary of the very brief discussion that took place during the workshop about the importance of including citizen and other public groups in the dialogue.

THE PUBLIC HEALTH VALUE OF PUBLIC–PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP1

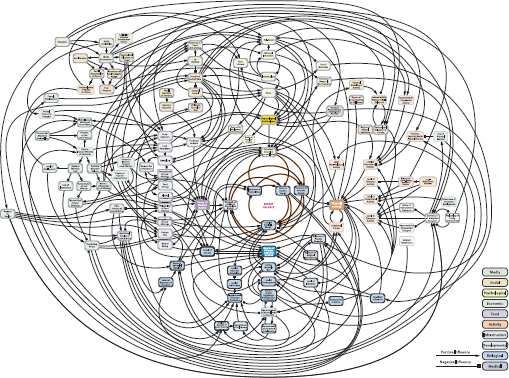

Many of today’s public health challenges would be well served by public–private partnership approaches, with all stakeholders engaged. Moreover, the complexity of some of today’s public health challenges, such as obesity, demands collaboration (Figure 2-1). As McGinnis said, “If there was ever a problem for which there is no easy, simple solution, it is the problem of obesity, and it requires, therefore, the committed, determined, and collaborative activity of every one of the stakeholders involved.” Finegood observed that people often respond to obesity and other complex problems by retreating, believing that the problem is beyond hope, assigning blame, and searching for simple solutions (Bar-Yam, 2004). “Clearly we need to go beyond that,” she said. Robert Post, deputy director of the USDA’s Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (CNPP), remarked that the only way to shift eating patterns is through harnessing the power and leveraging the resources of all “influencers.”

Who are those influencers? In Richard Black’s opinion, both the private and the public sectors play vital roles in modifying the food supply for public health purposes. As Black, vice president of global nutrition and chief nutrition officer at Kraft Foods, put it, the private sector needs to be part of the conversation because it makes the majority of food consumed in North America. Industry also generates important information about what, how, and why people eat and has the knowledge and expertise to modify the food supply in ways that address public health needs. Without active involvement of the food industry, Black asked, “how can we hope to modify the food supply?” The public sector needs to be involved because of its knowledge of public health and its insights into issues of which the food industry may be unaware. Black asked, “How can the food industry seek to modify the food supply if we don’t even know what the problem might be?”

Catherine Woteki, under secretary for USDA’s REE mission area, asserted that partnerships are necessary when the scope and scale of an endeavor are more than a single entity can or will support. She pointed to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH)–managed

![]()

1 This section is based primarily on remarks from the panel on the importance of partnering and the benefits and risks of partnerships moderated by David Castle. Panel members included Richard Black, William Dietz, Jonathon Marks, Robert Post, and Catherine Woteki.

FIGURE 2-1 This map of the interrelationships of the factors that influence obesity is displayed here to illustrate its complexity.

SOURCE: Foresight, 2007.

Biomarkers Consortium2 and the EPODE European Network3 as two examples of projects that would not be possible in nonpartnership formats.

Whether or not all sectors need to be involved, many participants asserted that one of the greatest benefits of working together to tackle complex public health problems is the greater variety of expertise, perspectives, and resources brought to the table when multiple sectors convene. One participant referred to the “added value” afforded by multiple voices. Another spoke of fewer “blind spots” and more movement in directions that would not otherwise be possible. The capacity to leverage multiple resources is especially important given that each sector has unique resources to contribute. Woteki pointed to the food composition and other long-term datasets maintained by the USDA and U.S. government biosafety level 3 and 4 laboratory capacity as two unique resources that government entities can contribute and specialized manufacturing facilities and knowledge about the chemistry of biologically active compounds in food as two unique resources that industry partners can contribute.

Other key benefits of partnership identified at various times during the workshop include the “team spirit” and enthusiasm fostered by the concerted effort and the sense of ownership among the various entities; enhanced credibility resulting from broad stakeholder involvement (one participant referred to the “greater probability of success” with a “broader buy-in”); and a consistency in messaging and action that helps the public to make better food choices.

Jonathan Marks, associate professor of bioethics, humanities, and law at the Pennsylvania State University, differentiated between benefits for the public versus private sectors. Two key benefits for the public sector are (1) to derive resources and expertise from the private sector and (2) to influence the activities of the private sector. Two key benefits for the private sector are (1) to generate good will and credit for corporate social responsibility and (2) to influence the activities of the public sector, including policy making and regulatory activities.

It is probably worth mentioning at the outset that although there was

![]()

2 The Biomarkers Consortium is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

3 The EPODE European Network was not discussed in detail at the workshop but was mentioned a few times as a model cross-sector initiative. Very generally, the EPODE (Ensemble, Prévenons l’Obésité des Enfants [Together Let’s Prevent Childhood Obesity]) European Network and the EPODE International Network are supported by multiple government, academic, and private partners. Both networks seek to build capacity in communities in several countries, including many in Europe as well as Australia and Mexico, around employing the EPODE methodology in community-based interventions. The EPODE methodology originated in France in 2004 and is designed to enable community stakeholders to implement an integrated community prevention program aimed at facilitating the adoption of healthier lifestyles. (See www.epode-european-network.com for more information.)

a great deal of emphasis during the workshop on obesity, given the urgent need for new and better tools to help people achieve and maintain weight loss (IOM, 2011), obesity was not the intended focus of this workshop. Other public health problems identified by participants as good candidates for collaborative approaches included foodborne illness, cardiovascular disease, chronic disease in general, and the health of older adults. For example, given that heart disease and stroke are, respectively, the first and third leading causes of death in the United States, speaker William Dietz, director of the Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), remarked, “In the next 10 years … I think it’s clear that the focus needs to be on dietary risk factors for cardiovascular disease, as well as obesity.”

Regardless of the public health problem at hand, Black challenged the workshop to pursue “those places where partnership is unavoidable” with respect to certain objectives. He observed that, too often, long-term collaborations are doomed by an automatic assumption of ill intent. The notion of the unavoidable, or essential, public–private partnership emerged as an overarching theme of the workshop discussion, with several participants echoing Black’s call. Castle cautioned, however, that it is important for public and private partners to weigh the long-term strategic value against the short-term tactical utility because a tactical, and seemingly essential, solution to a particular problem may end up distorting the mandate of either sector in the long term.

It appears that the same call is being echoed in American society at large, with the U.S. government continuing to downsize and look more toward private-industry funding to assist its public health efforts. Woteki mentioned a recent directive issued by President Obama aimed at increasing collaborative work between the public and private sectors and accelerating the transfer of federal research into the marketplace. However, as Castle pointed out, while the public sector incentive to partner may be growing, it is not clear how the private sector is going to respond. Companies must convince their shareholders and boards of directors that public–private partnering is a viable business strategy. He said, “I am not throwing cold water on the [U.S. government request for engagement], but … I think that there’s a corresponding dynamic that has to be addressed from the private sector as well.” Another workshop participant agreed that a company’s primary responsibility is to its shareholders and added that the risk of engaging with the public sector is that too much emphasis on “doing something for the better good,” or corporate social responsibility, leads to loss of credibility within the industry. Additionally, another participant noted the risk of failure and the impact of failure on a company. “People’s jobs are on the line,” she said, when industry money is spent on public health problems that are not solved. There is also some question about whether the public is

really prepared for this “shift in paradigm” toward public–private partnering. Public perception of public–private partnerships is already a concern, with private-sector engagement in public health raising serious concerns about conflict of interest. One participant emphasized the importance of a broad public buy-in from the beginning—for example, by involving NGOs early on. Conflict of interest aside, Castle observed that handing over a large portion of its governance mandate to private-sector interests could weaken government and raise questions about the legitimate role of government as a long-term orchestrator of the partnership in question.

FINDING COMMON GROUND FOR COLLABORATION

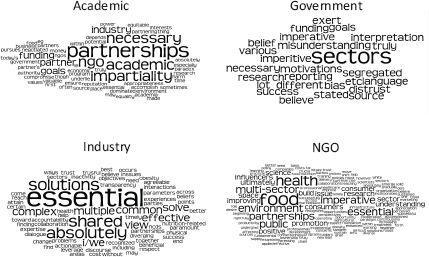

A major goal of the workshop was to reach an understanding of the different sectors’ paradigms—or deeply held set of assumptions, values, and beliefs about the way things are or should be that established boundaries or a framework to solve problems—and goals around multisectoral collaboration. To help reach that goal, participants were asked to articulate in the pre-workshop survey their sector’s paradigms (Figure 2-2) and goals

FIGURE 2-2 A “word cloud” illustrating results from the pre-meeting survey question “What is (are) your paradigm(s) about multisector partnerships in food and nutrition?” Words used more often in responses among individuals from a sector are the most prominent.

SOURCE: Diane Finegood, workshop presentation, November 1, 2011.

and then, during the workshop’s first breakout discussion, to explore goals in greater depth (Box 2-1).

Pre-Workshop Survey Results4

With respect to the different sectors’ paradigms, based on a qualitative analysis of pre-workshop survey results, Finegood observed that all four sectors (academia, government, industry, and NGO) agreed that partnership is important. However, their reasons for pursuing partnerships varied (see Figure 2-2). Finegood described the academic sector as goal-oriented, with a focus on impartiality and funding; industry as more process-oriented, with a focus on shared, common, and effective solutions; and NGOs as more content-oriented, with a focus on food, health, and the environment. Since only three government representatives responded to the pre-meeting survey, no conclusion could be drawn about the government sector’s paradigms.

With respect to goals, again there were some notable differences in the responses to the pre-workshop survey. Workshop participants from the academic sector are searching for access to funding while maintaining what they perceive as impartiality, with some concern that industry funding could impact that impartiality. Industry-sector representatives are searching for common messaging and a credible and equal voice at the table (i.e., private industry does not want to be, as Finegood put it, “sidelined by the pundits and editorialists”). Participants from NGOs are looking for common ground and respect for their contributions. Lastly, again, only three government representatives responded to the survey, but those that did mentioned funding and management of the potential for bias as key goals for public–private partnership.

Despite some major differences in the way the different sectors think about multisectoral collaboration and what they hope to gain from such collaboration, Finegood remarked there were also some important commonalities. Most of these were around data collection and knowledge, which participants from all sectors identified as key goals: “advance knowledge” and “provide evidence” (academic), “foster research” (government), “science base for regulation” and “technical advance” (industry), or “science base for messaging” (NGO).

Expectations: Despite Differences, Commonalities Exist5

Based on results from the pre-workshop survey and the report-back results listed in Box 2-1, McGinnis agreed with Finegood that although

![]()

4 This section is based on information presented by Diane Finegood.

5 This section is based on Michael McGinnis’s presentation.

BOX 2-1

Key Goals for Each Sector: Report-Back

from the First Breakout Session

For any complex situation, there are several different levels of intervention. Most interventions tend to be at what Diane Finegood described as the lower subsystem, or structural operating, level. It is much more difficult to intervene at the higher “goals†and “paradigm†systems levels. However, changes at the top can be the most effective. Thus, the pre-meeting survey and the meeting’s first breakout session both were aimed at uncovering and reaching some common understanding around the different sectors’ deepest held beliefs (or paradigms) and goals. See Figure 2-2 for a visual representation of the different sectors’ paradigms based on results of the pre-meeting survey. Below is a list of goals identified by workshop participants from each sector during the breakout session.

Academia

• Promote public health, food safety, and nutrition.

• Increase access to industry information—not just proprietary data but also information about how the food business operates.

• Maintain impartiality and operate with financial transparency and scientific integrity.

Government

• Build trust in public–private partnerships as an ethical, legitimate way to conduct business.

• Reduce the risk of foodborne disease.

there are important differences in what the different sectors hope to gain from multisectoral collaboration, there are also some important commonalities where collaboration can and should be pursued. Table 2-1 displays a detailed summary of McGinnis’s interpretation. He identified four common interests: (1) assessment (e.g., pooling data aimed at better understanding of how eating habits influence weight and health status); (2) research (e.g., developing a common research agenda aimed at better understanding of variation in basic caloric requirements); (3) marketing (e.g., synergizing social marketing efforts aimed at improving healthy habits); and (4) vision (e.g., working together to lay out a vision of what is possible). Any and all of these areas provide ample fertile ground for public–private collaboration. McGinnis proclaimed, “We need not only … suspend disbelief that [collaboration] can happen. We need to suspend complacency.”

• Identify common goals and mutual benefits for all partners.

• Leverage the unique resources, expertise, and perspectives that each partner brings to the table.

• Agree on measures of effectiveness.

Industry

• Solve major problems that we cannot solve alone.

• Dispel misperceptions about the food industry, demonstrate the food industry’s good intentions and expertise, and gain recognition from other sectors that the food industry can contribute to achieving common public health goals while also achieving its business objective(s).

• Arrive at a mutual understanding of the roles and issues that drive decision making across sectors so that achievable solutions can be sought.

• Recognize that emotions around food issues often cloud the ability to understand scientific findings and that the same findings from a single study are often interpreted differently by people from different backgrounds and with different belief systems.

• Experience business success by selling healthier products.

• Develop common messaging based on multisector buy-in.

NGO

• Share resources.

• Prioritize research gaps and identify achievable common goals.

• Establish win-win relationships among partners.

Partnerships aimed at producing meaningful change typically involve some degree of risk taking. At several times during the course of the workshop, several participants identified risk mitigation as an integral part of the public–private partnership planning process. For example, during the last breakout session, when groups were asked to consider partnership around a specific public health problem and to think about the types of questions and issues that potential partners should be focusing on, all three breakout groups spent a great deal of time discussing the need for risk mitigation. However, in his comments, Jonathan Marks argued that “balancing” is not the only way to think about risks and benefits, and that sometimes the

![]()

6 This section is based on Jonathan Marks’s presentation, plus additional remarks made by multiple participants, as indicated.

|

TABLE 2-1 Michael McGinnis’s Sample Synopsis of the Mission and Primary Functions of the Four Sectors (Academia, Government, Industry, NGO) |

|||

|

|

|||

| Sector | Mission | Primary Functions | Examples |

|

|

|||

| Academia | Science | Basic research | Identifying etiological factors that contribute to various public health problems, such as obesity |

| Applied research | Identifying interventions | ||

| Assessment | Evaluating interventions | ||

| Vision | Addressing the questions: What is needed, what is possible, by when, and how? | ||

| Government | Public health | Health protection | Regulating safety and labeling; conducting research |

| Health promotion | Marketing healthy behavior; conducting research on success | ||

| Services delivery | Fostering the availability and use of healthful products | ||

| Assessment | Monitoring health status and program results | ||

| Vision | McGinnis pointed to Healthy People 2020 as an example of the government sector exercising its vision of “what can be achieved over the next decade if we set ourselves to the task.” | ||

| Industry | Food sales | Food production and marketing | Researching and developing new products; developing strategies to move new products into the market |

| Returning profits to shareholders | Researching new products and strategies | ||

| Assessment | Assessing how well products are selling and whether strategies need to be shifted | ||

| Vision | Predicting what the market will look like in the future and evaluating the implications of that prediction | ||

| NGO | Awareness | Mobilizing public action | That is, around perceived shortfalls and injustices |

|

|

|||

| Sector | Mission | Primary Functions | Examples |

|

|

|||

| Assessment | Evaluating the state of play among key stakeholders | ||

| Vision | Addressing the questions: What is needed, what is possible, by when, and how? | ||

|

|

|||

risks to the public sector partner may be so great that there should be a presumption against the partnership proceeding.

Marks outlined some of the risks to the public sector partner and, in doing so, drew on the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition’s (UNSCN’s) list of potential risks of private-sector engagement as described in the committee’s private-sector engagement policy (UNSCN, 2006). These include the following:

• “Greater corporate influence over public policy”;

• “The opportunity costs of distraction from or less interest in activities which are not of interest to the private sector but may be important for nutrition goals”;

• “Regarding private sector engagements as ends in themselves, thereby undermining strategic direction”;

• “Loss of legitimacy with key constituencies and funders due to perceived co-optation by commercial interests”; and

• “Funding driven shifts in priorities at both international and national level, with fragmentation of public health/nutrition policies.”

The UNSCN places an emphasis, “above all,” on the need for “being open and clear about potential conflicts of interest” (UNSCN, 2006).

In addition to the UNSCN’s policy, Marks pointed out that a number of academics have written about other concerns, such as the subordination of the public institution’s values, the reorienting of its mission, and self-censorship. In relation to research, they have expressed concerns about the impact of private-sector engagement on research priorities, the outcomes and quality of the research, and the dissemination of research results. Marks emphasized that it is important to not only think about conflicts of interest but also consider more broadly (1) institutional integrity—focusing on the integrity of public institutions and on the integrity of the science—and (2) public trust in those institutions.

As one participant pointed out, most high-profile academics are themselves at risk of conflict of interest because they “build their entire careers around a particular perspective.” Yet, “they are not called out for those conflicts” and “would argue strongly that they don’t have a conflict.” Marks agreed that academic researchers may have nonfinancial conflicts of interest but argued that financial conflicts of interest at the institutional as well as the individual level are a more pressing challenge because of their systemic effects. Castle differentiated between conflicts of interest and biases and stated that the same individual-level non-financial biases apply to government officials as well. Another participant added, “You’re not going to find any person on this earth who does not have some sort of bias … we wouldn’t be human without it. The real question is, How do we manage it and what do we put in place as safeguards?”

So how are personal biases and institutional conflicts of interest managed and safeguarded against? There was very little dialogue about the former, other than recognition that personal bias exists and that it differs from financial conflict of interest. However, there was a great deal of debate on how to manage conflict of interest. Castle referred to the “all-or-nothing” crowd that advocates for perceived, or potential, conflicts of interest to be addressed simply by not allowing academic or government investigators to become involved with industry-funded research. That approach, Castle said, makes it very difficult to “actually get things done in the long run.” Several workshop participants expressed frustration at the cost of devaluing and excluding food industry expertise and knowledge. One participant remarked, “One of the frustrating things I see is that the folks that are making the food every day and are responsible for getting it right every day seem to be not having as much say-so as they ought.” Another participant referred to the “arrogance” of academic partners who think that they know what all the problems are. A couple of workshop participants pointed out how academic investigators who don’t trust industry risk losing touch with the problems that industry perceives as being the most important. Castle noted, “We’re starting to see the relevance of a lot of the work that gets done in universities coming under increased scrutiny.” Woteki pointed out that most funding for agricultural and food research comes from the private sector and that many academic scientists’ entire careers have been funded by industry. She said, “To say, as is done now in many different kinds of meetings, that we want to exclude people who are funded by the private sector, we’re going to be losing a very large body of expertise in the food and agricultural disciplines.”

There is no rule for engagement, Castle asserted. Some situations call for obvious choices; others, for more nuanced decision making. In some instances, he said, it may be desirable not to partner with certain organiza-

tions. For example, when dealing with childhood obesity, it would probably be very difficult to maintain credibility in certain spheres if someone were to partner with an organization known for using state-of-the-art advertising to children. Marks agreed that “in certain circumstances, the risks are so great that the presumption might be against the activity.” He said, “There might be good reasons not to partner on certain initiatives with certain actors in order to achieve that end.” In other situations, Castle argued, it may be desirable to maintain proximity to industry as a way to gather information. For example, Castle mentioned his involvement in a current project where a senior executive from Monsanto is serving on the scientific advisory board. It was a worthwhile risk, Castle said, because of the benefits of knowing a private-sector standpoint on the issues. To alleviate the risk, the influence of that particular private-sector participant is limited by very clear rules of engagement. As another example, Black described the approach taken by the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Department of Nutrition for Health and Development: food industry representatives do not participate in developing policy, but they do provide information to those who are developing the policy.

While the risks created by conflict of interest are important concerns, these are not the only risks. Other risks identified by workshop participants at various times during the course of discussion include the inappropriate sharing or use of information outside the partnership; the presence of ineffective partners who do not take action or who do not “really jump in and roll up their sleeves along with everybody else in the partnership”; the likelihood that a partnership constitutes a tacit endorsement of a company or product; the presence of a “halo shadow,” whereby another product or activity within a certain entity might cast a shadow on the partnership; the likelihood that a partnership project is too focused and, as such, does not address all options for dealing with a specific problem; and the presence of partners with spurious motives.

Almost all of the workshop discussion focused on the interaction between government, private industry, academia, and nongovernmental organizations, with little mention of the role of consumer, or citizen, participation. Yet, as one participant stated, “The fact that a partnership is even contemplated means it’s a heavy matter. It’s going to result in or heavily influence public policy.” The participant asked, “At what point are consumer representatives, citizen representatives, legitimate partners?” Jonathan Marks agreed that public participation is an important part of partnership and encouraged workshop participants to think about how

public–private partnerships could be framed to include public participation. One participant noted the very effective role that nonprofit organizations have played over the years in engaging industry in constructive conversations. Marks added that there are many ways that public interest can be represented, not just through so-called public-interest groups.