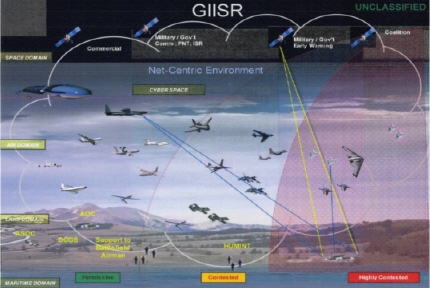

As discussed in Chapter 1, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities enable the U.S. Air Force (USAF) to be aware of developments related to adversaries worldwide and to conduct a wide variety of critical missions, both in peacetime and in conflict. An idealized picture of a global, integrated ISR system is shown in Figure 2-1. It involves a networked system of systems operating in space, cyberspace, air, land, and maritime domains. These systems include planning and direction, collection, processing and exploitation, analysis and production, and dissemination (PCPAD) capabilities linked together by a communications architecture. As suggested in Figure 2-1, different ISR systems may be required in permissive, contested, and highly contested environments.

Although this idealized “enterprise” picture of global, integrated ISR systems is highly desirable, it is not yet treated as an enterprise.1 ISR systems in different domains tend to be owned and operated by different governmental agencies for the accomplishment of their own particular missions, and even systems operating in the same domain often do not communicate with one another. There is no coordi-

_______

1Enterprise” is defined as the set of all U.S. ISR capabilities operating in multiple domains, irrespective of which U.S. agency or organization owns the capability, that are capable of informing decision makers at all levels about the activity of an adversary or potential adversary.

FIGURE 2-1 Global, integrated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operational view. NOTE: Acronyms are defined in the list in the front matter. SOURCE: Col Scot Gere, Chief, GIISR Core Function Team. “Core Function Lead Integrator (CFLI) Construct and GIISR Capability, Planning, and Analysis.” Presentation to the committee, January 25, 2012.

nated planning process in place among the many organizations that are stakeholders in ISR systems, and consequently no true enterprise architecture for ISR exists.

This state of affairs is hardly surprising. Generally speaking, the intelligence community (IC) controls the planning and acquisition of national space assets and assets for collecting the various “INTs” (e.g., SIGINT [signals intelligence], HUMINT [human intelligence], among others), while the Air Force and the other military services focus on organizing, training, and equipping forces with ISR capabilities in space, air, and cyberspace (see Box 2-1).2 Planning and budgeting for ISR missions among these agencies and services are generally done independently; even within a single agency the ISR planning and acquisition programs are often stovepiped, with the resulting systems lacking the standards and common communications systems that would enable them to operate in the coordinated fashion depicted in Figure 2-1.

_______

2The IC is composed of 17 member organizations and includes the National Reconnaissance Office, the National Security Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. For more information, see http://www.intelligence.gov/about-the-intelligencecommunity/member-agencies/. Accessed May 24, 2012.

BOX 2-1

The Cyberspace Domain

Cyberspace, a relatively new and rapidly evolving operational domain for the Department of Defense (DoD) and the military services, is defined as “a global domain within the information environment consisting of the interdependent network of information technology infrastructures, including the Internet, telecommunications networks, computer systems, and embedded processors and controllers.”a ISR can be substantially augmented or hindered in the cyberspace domain. ISR sensors can be augmented by the ability of cyber information to provide geolocation information and movement information on adversarial and friendly systems. This capability can allow sparse assets to be deployed elsewhere or to obtain information more effectively, allowing rapid, minimal observations.

Cyberspace is human-made, which makes the cyber domain different from the natural domains of air and space, although cyber capabilities can exist in all natural domains. Components, subsystems, and systems exist in the cyber domain: these include networks, globally integrated and isolated; physical infrastructure; electronic systems; portions of electromagnetic systems;b and industrial control systems known as “SCADA” (supervisory control and data acquisition) systems. The latter are computer systems that monitor and control industrial, infrastructure, or facility-based processes.

Beyond these definitions, the committee offers the view that any asset with computational capability— including avionics and flight control systems, tactical communications and data links, and command-and-control systems onboard and off-board—should be considered to be in the cyber domain.

__________

aDoD. 2010. “Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Joint Publication 1-02). 8 November. As amended through 15 October 2011.” Available at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp1_02.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2012.

bDoD. 2007. “Electronic Warfare.” Joint Publication 3-13.1. Available at http://www.fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/jp3-13-1.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2012.

The Deputy Chief of Staff of the Air Force for ISR (AF/A2) and others desire that the Air Force conduct its ISR Capability Planning and Analysis (CP&A) process at an enterprise level rather than on a system-by-system basis.3 To produce optimum capability, the Air Force wishes to treat ISR data and information as a system-of-systems enterprise. Such an enterprise needs to be composed of end-to-end solutions that include all the elements of PCPAD—planning and direction,

_______

3On a system-by-system basis, individual ISR systems are considered in isolation from other ISR systems. The result may be that an ISR system other than the one in question may sufficiently provide the sought-after capability requirement, thus obviating a new acquisition need. Conversely, the system in question may not be needed at all in view of the contribution of another system not considered. Further, the combination of otherwise independently acting systems may together solve the capability requirement. Conversely, in an ISR enterprise, all relevant ISR systems are considered regardless of ownership as long as their capability contributes to understanding an adversary or potential adversary.

FIGURE 2-2 The intelligence process. SOURCE: Department of Defense. 2007. Joint Intelligence. Joint Publication 2-0. Washington D.C.: Department of Defense. Available at http://www.fas.org/irp/DoDdir/DoD/jp2_0.pdf.

collection, processing and exploitation, analysis and production, and dissemination— referred to by the Joint Staff as the intelligence process, or the Joint Intelligence Cycle (see Figure 2-2).4 Deficiencies in any PCPAD element can reduce the effectiveness of the overall intelligence cycle.5,6 For example, as the Air Force is painfully aware, it does little good to acquire the capability to collect data from a wide-area aerial surveillance system if those data cannot be processed and turned into actionable information within a recognized time period of usefulness.

One of the major issues posed by the integration of new technologies into an existing mix of ISR systems is sustainability. For example, the protracted conflict in Southwest Asia and the demands of the kind of the counterinsurgency (COIN)

_______

4DoD. 2007. Joint Intelligence. Joint Publication 2-0. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense. Available at http://www.fas.org/irp/DoDdir/DoD/jp2_0.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2012.

5For additional information on the PCPAD process, see Jesse Flanigan, 2011, “Intelligence Supportability Analysis for Decision Making.” Available at http://spie.org/documents/Newsroom/Imported/003661/003661_10.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2012.

6GAO. 2011. “Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance: Actions Are Needed to Increase Integration and Efficiencies of DOD’s ISR Enterprise.” Available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-11-465. Accessed July 28, 2011.

warfare fought there caused the combatant commander to require a large number of quick-reaction capabilities (QRC) and new ISR capabilities. This quick-reaction, or “Urgent Operational Need” (UON) process worked well in delivering to the warfighter important operational capabilities, but the process is not sustainable in the long run. Because many QRC projects result in the fielding of new technologies and systems for which there is little experience and for which long-term sustainability is an unknown, the costs and difficulties in repairing, training for, supplying, and otherwise supporting a host of one-of-a-kind systems are large challenges for the military services.7 With the conflict now diminishing, the Air Force needs to determine if it should—or how it should—permanently bring these new capabilities, such as non-traditional ISR (NTISR), into its ISR enterprise.8,9 The Deputy Chief of Staff of the Air Force for ISR recently noted:

The Air Force will take “a year or two” to decide whether to keep, expand, or jettison a variety of “boutique” intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance capabilities created as ad-hoc solutions to special needs during the past 10 years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan …. These “quick-reaction capability” programs, such as Gorgon Stare and Blue Devil, to name just two, “need to play out” a while longer so USAF can determine if they are worth the expense of continuing …. Gorgon Stare vastly increases the ISR “take” from an MQ-9 Reaper, for instance, but the Air Force is staggering under the weight of the data the systems are generating …. Gorgon Stare and Blue Devil generate “53 terabytes a day” of data, equivalent to “12 years of video” …. Collectively, … USAF’s high-definition video systems are generating six petabytes, or “80 years” of high-def video a day. USAF will have to invest heavily in processing, exploitation, and distribution systems to keep up with the flow, and will need lots of analysts skilled at synthesizing “all source” ISR….10

_______

7A report from the National Research Council (NRC) identifies the long-term sustainment of rapid prototypes as a potential major issue. NRC. 2009. Experimentation and Rapid Prototyping in Support of Counterterrorism. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

8“Non-traditional ISR” is defined as follows: “NTISR is the concept of employing a sensor not normally used for ISR as part of an integrated collection plan developed at the operational level for preplanned, on-call, ad hoc, and/or opportune collection.” SOURCE: USAF. 2007. Air Force NTISR Functional Concept.

9The Vice Commander of the Air Combat Command used another example of the need for an ISR Capability Planning and Analysis process that can bend and adjust existing programs of record so that they produce capabilities that take advantage of NTISR. He noted that while new fighter aircraft have immensely powerful ISR collection capability, they lack the ability to get the ISR information into the hands of those who can use it. “This requires changes in both material and non-material ways in such areas as command and control, data links, processing and dissemination. The Air Force has known this for over a decade, but the ability to describe and adjust to changes to make this NTISR capability a reality has not developed. A faulty CP&A process could be a major factor in why this failure has occurred” [emphasis added]. SOURCE: Lt Gen William Rew, Vice Commander, Air Combat Command. Personal communication to the committee, January 25, 2012.

10John Tirpak. 2012. “Boutique ISR,” Air Force Magazine, February 16. Available at http://www.airforce-magazine.com/DRArchive/Pages/2012/February%202012/February%2016%202012/BoutiqueISR.aspx. Accessed March 22, 2012.

According to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction (CJCSI) 3170.01G, there are three key Department of Defense (DoD) processes—that is, the requirements process, the acquisition process, and the planning, programming, budgeting, and execution (PPBE) process—that need to work in concert to deliver the capabilities required by the warfighter.11 Each process is ongoing, and keeping all three synchronized has been problematic. The Air Force has long used a variety of methods and tools to evaluate and inform its ISR requirements, acquisition, and PPBE decisions. To ensure that these three key processes are more synchronous, the Air Force has recently undertaken steps to improve its ISR CP&A process. These efforts have gone a long way toward developing more rigor and collaboration in the identification of operational needs and the acquisition of systems.

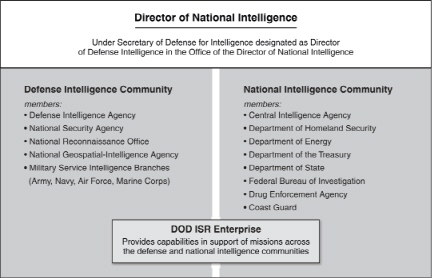

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE AIR FORCE ISR PLANNING PROCESS

In 2008, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) called for the DoD to have an integrated ISR enterprise architecture and framework for providing and considering trade-offs among future potential investment alternatives.12 This action has yet to be taken, although the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Intelligence) (OUSD[I]) announced in 2010 its intention to create a Defense Intelligence Mission Area Enterprise Architecture. A June 2011 GAO report noted the lack of an implementation plan and time line for this new enterprise architecture.13 Any Air Force enterprise ISR perspective and architecture would have to be consistent with this Defense Intelligence Mission Area Enterprise Architecture when it is developed. The magnitude of this challenge is depicted in Figure 2-3, which shows the number of organizations that have some responsibility for ISR. The Air Force is but one, albeit large, ISR capability provider to the nation. Decisions made regarding Air Force ISR capabilities need to take into account the organizations listed in Figure 2-3. Many of these key organizations are responsible for creating, evaluating, and using Air Force ISR capabilities.

In providing ISR capabilities, the Air Force is required to make investment decisions that recognize that the requirements for its ISR capabilities come either

_______

11CJCSI. 2009. “Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System.” CJCSI 3170.01G. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense. Available at http://www.dtic.mil/cjcs_directives/cdata/unlimit/3170_01.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2012.

12GAO. 2008. Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance: DoD Can Better Assess and Integrate ISR Capabilities and Oversee Development of Future ISR Requirements. Available at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08374.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2012.

13GAO. 2011. Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance: Actions Are Needed to Increase Integration and Efficiencies of DOD’s ISR Enterprise. Available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-11-465. Accessed July 28, 2011.

FIGURE 2-3 The relationship of the Department of Defense’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) enterprise to the intelligence community. SOURCE: GAO. 2011. Intelligence, Surveillance, And Reconnaissance: Actions Are Needed to Increase Integration and Efficiencies of DOD’s ISR Enterprise. Available at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d11465.pdf.

from Joint combatant commanders or from the nation’s top-level decision makers. In the DoD, capability development requirements are vetted through two principal processes, the Joint Urgent Operational Need (JUON)/Urgent Operational Need (UON) process and the Joint Capabilities Integration Development System (JCIDS) process, as they become formalized and validated by senior decision makers in the DoD. The distinction, in principle, is that the JUONs and UONs are intended to be schedule-constrained and limited in scope, size, and potential performance, with a focus on speed to need. The normal process, JCIDS, is intended to ensure rigorous analysis and study in defining the capability need before entering the technology development phase of the acquisition process.

1. JUONs and UONs from the Combatant Commands (COCOMs) or service Major Commands (MAJCOMs) are prioritized by the COCOM/MAJCOM leaders and sent to the Joint Staff and the military services to prioritize and provide solutions according to a “time to field” focus, with a target of less than 12 months to field a solution.

2. In the JCIDS, or the military service-specific capabilities development process for non-Joint requirements, Initial Capabilities Documents (ICDs)

document the required capabilities needed following a Capabilities-Based Assessment (CBA) methodology. In the Joint Staff, the J8 runs the JCIDS process. In the Air Force, the AF/A5 runs the corporate capabilities process through the Air Force Requirements Oversight Council (AFROC), with the Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force (VCSAF) validating any recommendations. In both JCIDS and Air Force processes, MAJCOMs or COCOMs sponsor the requirements into the processes.

Requirements are formally documented in ICDs and Capabilities Description Documents (CDDs) that must be validated by either the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC), which is chaired by the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (VCJCS), or the VCSAF. The JROC publishes its final validation of an ICD in a JROC Memorandum and the AFROC in an AFROC Memorandum. At this point, the requirements are pushed back to the lead MAJCOM for funding and into the Acquisition Systems through the Materiel Enterprise of a particular service (e.g., Air Force Materiel Command) for development.14 In assessing and planning for its ISR capabilities, the Air Force has to consider the entire set of Joint capabilities provided by the other services as well as the needs of the COCOMs.

In 2009 and 2010, AF/A2 produced and used what was called the ISR Flight Plan to articulate how Air Force ISR would meet current and future challenges of air, space, and cyberspace operations and address all doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy (DOTMLPF-P) considerations.15 The ISR Flight Plan translated priorities and guidance in the Air Force Strategic Plan to “create a vector for ISR capability development, modernization and recapitalization.” It was to be the guiding source for the annual planning and programming guidance (APPG) and was intended, along with the Air Force ISR Strategy, to be the Air Force Core Master Plan for Global Integrated ISR.16 The major tool used in creating the ISR Flight Plan was the ISR Capabilities Analysis Requirements Tool (ISR-CART), which is a database and searchable repository of requirements and ISR programs and capabilities (see Box 2-2).

_______________

14Lt Col Nathan Cline, ISR Plans and Integration Division, HQ AF/A2DP. Personal communication to the committee, May 24, 2012.

15Lt Gen David Deptula (USAF, Ret.), Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director, Mav6. “The Air Force ISR Flight Plan: Origin, Rational and Process.” Presentation to the committee, October 6, 2011.

16USAF. 2009. “Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Flight Plan.” Memorandum for ALMAJCOM. June 18. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Staff.

BOX 2-2

The ISR Capabilities Analysis Requirements Tool (ISR-CART)

The ISR Capabilities Analysis Requirements Tool (ISR-CART) is maintained by the Air Force Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Agency (AFISRA) and sponsored by the AFISRA’s A-5/8/9 directorate. The database contains information on many types of intelligence, including mission-related data, from the intelligence community, the other services, the Joint Staff, and industry.

The ISR-CART, an interactive tool, is accessible to authorized users on the Secret Internet Protocol Router Network (SIPRnet) and the Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communications System (JWICS). The SIPRnet is the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) classified version of the civilian Internet; it carries information up to and including the Secret classification. JWICS is a similar system of interconnected computer networks primarily used by the DoD, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the U.S. Department of Justice to transmit classified information at Top Secret or higher levels.

The ISR-CART is the repository of a wealth of information, including nearly all ISR requirements, ISR system attributes and limitations, and ISR capability needs, gaps, and solutions.a The database allows users to access information needed to make informed capability and modernization planning decisions and to meet future technology challenges. It provides the ability to link all areas, from stated operational need to proposed solutions, actual research and development (R&D) to delivery of an operational system. ISR-CART has a modularized design enabling links among multiple categories. The modules of ISR-CART include the following: tasks/needs, gaps, solutions, R&D efforts, systems (including parametric information), points of contact, references/bibliography (such as capability guides, concepts of operation), and a glossary.

__________

aUSAF. 2009. “Intel Deputy Unveils ISR Capability Planning Process.” Available at http://www.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123143770. Accessed February 27, 2012.

Guided by both directive and Air Force instruction signed by the Secretary of the Air Force (SECAF) and Chief of Staff of the Air Force (CSAF), the ISR Flight Plan was put together in a collaborative, iterative process led by AF/A2, with representation and subject-matter experts from the MAJCOMs, including the Air Force Materiel Command’s (AFMC’s) Air Force Research Laboratory, the Air Force ISR Agency (AFISRA), the National Air and Space Intelligence Center, and the Headquarters Air Force (HAF) staff, including AF/A5, AF/A7, AF/A8 and SAF/ AQ. The ISR Flight Plan began by considering strategic guidance and then tied in to the results of the ISR work of the capability-based planning (CBP) and the JCIDS processes. The ISR Flight Plan process culminated with a variety of options for HAF consideration in the creation of the Program Objective Memorandum (POM) of the PPBE process.

The ISR Flight Plan took more than a year to complete and required many hours of work from many people in a variety of Air Force organizations. It was well received, as it filled a need in the assessment of ISR capability. Until the ISR Flight Plan, there had been no other attempt at a holistic, across-the-Air-Force examination of ISR requirements, capabilities, needs, gaps, and solutions to yield options to guide ISR planning and programming. However, its completion came just as the Air Force leadership decided to undertake a new method of determining programmatic needs of core Air Force functions.

The Core Function Lead Integrator Construct

In 2010, the Secretary of the Air Force and Chief of Staff of the Air Force decided that each of the Air Force’s 12 Service Core Functions would have an annual Core Function Master Plan (CFMP) developed under the guidance of an Air Force MAJCOM commander acting as a Core Function Lead Integrator (CFLI).17,18 For one of these core functions—Global Integrated ISR, or GIISR—it was determined that the CFLI would be the Air Combat Command (ACC). In 2011, each CFLI was tasked to produce a baseline CFMP. In this work they were to align strategy, operating concepts, and capability development with requirements and programmatic decisions about the Service Core Function over a 20-year period.

The ISR Flight Plan, delivered once, was not updated for the following year, as resources and leadership attention of the Air Force were turned to CFMP production for GIISR and the other CFMPs. AF/A2 staff was left to wonder what to do with the processes of the 2009 ISR Flight Plan and what would be the relationship of the CFLI with the HAF staff responsibilities in capability planning and assessment. Some of the results of the ISR Flight Plan (such as gap analysis)—and some methods and tools (such as the ISR-CART)—were used in the development of the 2010 GIISR CFMP. AF/A2 renamed the ISR Flight Plan process the ISR CP&A process.

_______________

17Service Core Functions define the Air Force’s key capabilities and contributions as a service. Service Core Functions correspond to the specific primary functions of the service as described in DoD Directive 5100.01. SOURCE: USAF. 2012. “GIISR Operations. Air Force Doctrine Document 2-0. Dated 6 January.” Available at http://www.fas.org/irp/doddir/usaf/afdd2-0.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2012.

18Following are the names of the Air Force Service Core Functions: (1) Nuclear Deterrence Operations, (2) Air Superiority, (3) Global Precision Attack, (4) Personnel Recovery, (5) Command and Control, (6) Global Integrated ISR, (7) Space Superiority, (8) Cyberspace Superiority, (9) Rapid Global Mobility, (10) Special Operations, (11) Agile Combat Support, and (12) Building Partnerships. SOURCE: Col Brian Johnson, Chief, Air Force Plans and Integration Division for the Deputy Chief of Staff, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance, Headquarters, U.S. Air Force. “Air Force ISR CP&A Overview.” Presentation to the committee, October 6, 2011.

In summary, the Air Force employs two overlapping processes for planning future ISR investments: the ISR CP&A process, which is derived from the earlier ISR Flight Plan and led by the AF/A2; and the CFLI process, led by the Air Combat Command. These processes are described below. At this writing, the two processes have not been fully reconciled, with consequences that are discussed later in this chapter.

THE CURRENT AIR FORCE ISR CAPABILITY PLANNING AND ANALYSIS PROCESS

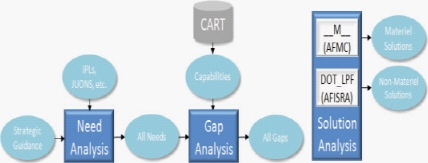

The current Air Force ISR CP&A process, as shown in Figure 2-4, is informed and guided by strategic direction provided by the White House National Security Council, the U.S. Congress, the DoD, the IC through the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), and others. This guidance is handed down at different times and takes many written forms, including National Intelligence Estimates, the Five-Year Defense Plan, Global Threat Analyses, and various global trend studies often conducted by Federally Funded Research and Development Centers.

The Needs Analysis phase of the CP&A process attempts to ensure that all ISR needs are gathered from across the Air Force ISR enterprise. Primary participants in the Needs Analysis phase are AF/A2 and its direct reporting organization, AFISRA, as well as the COCOMs, which typically express their needs through Integrated Priority Lists, and the MAJCOMs, which represent the interests of their affiliated COCOMs. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and its mission partners, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and the National Security Agency (NSA), which have their own capability planning and analysis processes, appear to engage only tangentially in the Air Force process.

The Needs Analysis function produces an unconstrained, “1-to-N” list of ISR needs. No attempt is made at this step in the current process to prioritize or filter needs. By gathering all needs, the process seeks to prevent needs that might not be relevant in today’s mission environment from falling on the cutting-room floor. However, gathering all needs each time through the process can be very time- and labor-intensive and may not be necessary for situations in which investment decision makers are interested in rapid answers to focused questions.

The Gap Analysis function matches each need on the list with known ISR capabilities. Needs that have no matching capabilities are identified as gaps. Major participants in this phase of the process include AF/A2, AFISRA, the GIISR CFLI, and MAJCOM representatives. As with the Needs Analysis phase, participation by the IC appears to be more opportunistic than systematic.

The primary tool used to match capabilities with needs is the ISR-CART database. (See Box 2-2.) ISR-CART, which is maintained by AFISRA, provides a comprehensive, searchable store of needs, capabilities, and gap information, indexed by a variety of metadata types. Although the physical process of matching needs

FIGURE 2-4 Major elements, inputs, and outputs of the current Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Capability Planning and Analysis (ISR CP&A) process of the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Air Force for ISR (AF/A2). NOTE: Acronyms are defined in the list in the front matter. SOURCE: Derived from Col Brian Johnson, Chief, ISR Plans and Integration Division (AF/A2DP), Headquarters, U.S. Air Force, “Air Force ISR CP&A Overview.” Presentation to the committee, October 6, 2011.

with capabilities is completely manual, and therefore labor- and time-intensive, the ISR-CART information repository serves as a highly valuable “one-stop shop” for obtaining vital information needed to support the Needs and Gap Analysis processes.

The first, and to date apparently only, pass through the Gap Analysis phase of the ISR CP&A process yielded a well-documented list of more than 200 gaps. Items on this list were further grouped into 12 prioritized categories.19 The Solutions Phase then began the process of analyzing potential solutions for each gap category. Materiel solutions were investigated by AFMC, and gap areas were assigned to appropriate Capability Management Teams that included representatives from various Air Force science and technology and acquisition stakeholder communities.20 Non-materiel solutions, or so-called DOT_LFP solutions, were investigated under the leadership of AFISRA.

Although AFMC and AFISRA made valiant attempts to investigate materiel and non-materiel solutions, the process appears to have become bogged down by the lack of manpower and funding resources required to adequately investigate more than a small number of gap areas. In addition, the ISR CP&A process was paused at the request of the ACC as the GIISR CFLI stood up and began the process

_______

19Col Brian Johnson, Chief, ISR Plans and Integration Division (AF/A2DP), Headquarters, U.S. Air Force. “Air Force ISR CP&A Overview.” Presentation to the committee, October 6, 2011.

20Brig Gen Dwyer Dennis, Director, Intelligence and Requirements Directorate, Headquarters AFMC, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. “Capture the Past, Build the Future: Capability Planning and Analysis.” Presentation to the committee, November 10, 2011.

of defining the roles and responsibilities.21 Following this summary of the current process is a more in-depth look at both how this process came to be and what it is.

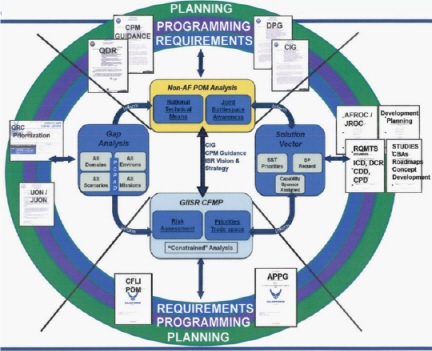

THE CORE FUNCTION LEAD INTEGRATOR PROCESS

As noted above, in 2010 the Air Force undertook a new service-wide capabilities-based planning method as part of a revised strategic planning process. At the heart of this process are annually iterated CFMPs developed by Air Force MAJCOM commanders who act as CFLIs for specific Service Core Functions. The CFLI is the authoritative source for detailed planning within each Service Core Function. As stated above, the CFLI for the GIISR core function is the commander of the Air Combat Command.

There are three aspects of the Service Core Function construct that are noteworthy. First, CFMPs for two Service Core Functions—GIISR and Command and Control—are unique among CFMPs because they are enablers for all other Service Core Functions. Second, the Space Superiority and Cyber Superiority Service Core Functions, both of which have strong connections to the ISR enterprise, are led by a different CFLI (Air Force Space Command [AFSPC]) than the CFLI that leads the Service Core Functions for GIISR and Command and Control. Third, the management of those items that would constitute NTISR is fragmented among other ACC CFMPs. The potential exists for ISR capabilities to be undervalued, underfunded, or completely missed by a given CFMP. If the Air Force wishes to integrate NTISR collection capability from platforms, such as its newest fighters, the CFMP or ISR CP&A processes may have to point to the budgetary choices among several non-ISR programs in order to pay for such capability. For example, the Air Force will have to ensure that the platforms have necessary data links and that the command-and-control structure is capable of tasking the platforms in both near real time and real time, and a capability will be needed to turn the data collected into actionable information in order to support PCPAD. The elements of this example are each in separate CFMPs. It seems that none of the CFMPs has the priority to make NTISR a reality; none has lead responsibility in this fragmented structure.

As the basis for its work in producing the 2011 GIISR CFMP, the Air Combat Command started with the Gap Analysis and the 19 ISR Gap Focus Areas that had resulted from the 2009 ISR Flight Plan. Its next step was to conduct an assessment of risks involving these gaps as applied to three representative scenarios found in operational plans, each of which require Air Force GIISR support. This analysis was constrained both by external guidance and by the number and type of ISR capabili-

_______

21Col Scot Gere, GIISR CFT Chief, Air Combat Command, Langley Air Force Base. “Core Function Lead Integrator (CFLI) Construct and GIISR Capability, Planning, and Analysis.” Presentation to the committee, January 25, 2012.

ties considered likely to be available for each scenario examined. This analysis was followed by a determination of trade-space priorities done iteratively with AFMC and other stakeholders to determine the types of forces needed and how best to sustain, replace, and improve these capabilities, along with the associated costs. This yielded a list of prioritized capability gaps and science and technology efforts that was itself refined and adjusted by a council of knowledgeable colonels from across the Air Force. The work was then passed between the council of colonels and a solutions working group for pre-acquisition capability planning and analysis or on to developmental planning to produce relevant materiel and/or non-materiel solutions.22

Figure 2-5 shows the GIISR CFLI’s view of the ISR process for developing planning, programming, and requirements outputs and depicts the relationships of various major processes and the products that flow from or into these processes. The ring of activities in the middle of the chart shows the relationship of Gap Analysis, non-Air Force POM analysis, GIISR CFMP development, and the solutions vector. In Gap Analysis, ISR gaps are collected and reviewed by all ISR stakeholders and consolidated into the ISR-CART database maintained by AFISRA. In the non-Air Force POM analysis, AF/A2 acts as the service interface with the IC and others outside the Air Force and has the preferred vantage point for understanding gaps in and outside the Air Force. AF/A2 is also required to influence and interpret the Quadrennial Defense Review and the Defense Planning Guidance and to produce its own guidance as the ISR Capability Portfolio Manager.

Informed by external guidance and the current annual planning and programming guidance (APPG), the GIISR CFLI applies a scenario-based assessment to link gaps to operational and force management risk and then prioritizes areas for solution work. The CFMP also creates GIISR planning force proposals that facilitate Air Force integration for a balanced POM submission. Courses of action developed from previous solution work are inserted into programmatic action while at the same time requirements are developed and updated. In the solutions vector, the council of colonels from stakeholder organizations reviews the prioritized areas from the CFMP, considers the national inputs from AF/A2, and provides a vector for capability working groups. These groups collect possible materiel and non-materiel solutions and present their findings in the form of courses of action. The working group may also recommend JCIDS actions to drive developmental planning requests that can be undertaken. Note the outer concentric rings in Figure 2-5

_______

22A “council of colonels” is a term not officially defined; however, it is understood to mean a council of persons of that rank who represent the interests and perspectives of their various organizations in a discussion or a decision-making forum about what that group believes about a certain issue or matter. Their views are then forwarded to those in higher authority for either information or further deliberation.

FIGURE 2-5 Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) planning, programming, and requirements outputs. NOTE: Acronyms are defined in the list in the front matter. SOURCE: Col Scot Gere, Chief, GIISR Core Function Team. “Core Function Lead Integrator (CFLI) Construct and GIISR Capability, Planning, and Analysis.” Presentation to the committee, January 25, 2012.

indicating the relationship of these processes with planning, programming, and requirements processes.

Both the CFMP and the ISR CP&A processes have positive attributes as well as areas for improvement. On the positive side, they are generally inclusive, make a strong effort to use data to inform discussions, and do the best that one could do with an approach that is nearly all manual and labor-intensive. However, the CFMP process, like the ISR Flight Plan before it, is cumbersome and slow and cannot rapidly respond to changes in guidance, urgent warfighter needs, or commanders’ needs for quick answers to specific questions. As with the ISR Flight Plan, the GIISR CFLI work took months, consumed many hours of work by subject-matter experts, and utilized no tools other than parametric analysis and the ISR-CART. Further, it was necessary to cross-check with the CFLI staffs developing the CFMPs for Space Superiority and Cyberspace Superiority to eliminate underlap and overlap with the ISR needs of those core functions, and it is not clear to the committee

whether or not the underlap/overlap analysis was adequate and correct given the time constraints of the CLFI process.

Space Superiority and Cyberspace Superiority Core Function Master Plans

The Air Force Space Command is the CFLI for the Space Superiority and Cyberspace Superiority Service Core Functions, both of which have ISR content.

Space Superiority

In conducting its work as the Space Superiority and Cyberspace Superiority CFLI, the AFSPC conducts its own CP&A process, which parallels the ISR CP&A process. The AFSPC did participate in the ISR CP&A needs and gap analysis process in 2010. However, there existed some confusion over roles—for example, budget authority—and whether AF/A2 had the clear enterprise role to lead the definitive plan for the Air Force ISR portfolio. The AFPSC believed that AF/A2 had budget authority in the ISR CP&A planning process in the first round of the CFLI process, showing confusion over roles and responsibilities. It seems that more clarification and communication are required among those CFLIs whose responsibilities overlap in ISR capabilities, specifically Space Superiority, Cyberspace Superiority, and GIISR.

Cyberspace Superiority

Owing to the emerging nature of cyberspace operations, the committee offers additional analysis on the concept of Air Force cyberspace operations, the role of the Air Force in the context of the overall DoD/IC cyberspace enterprise, and the relationship of the Air Force to the ISR CP&A and CFLI planning processes. There is a multidimensional relationship between the ISR and cyber missions and capabilities. There are three missions from a cyberspace perspective: support, defense, and force application. ISR is a crosscutting capability that can be applied holistically with other core functions to enable cyberspace missions. Conversely, Cyberspace Superiority supports and is supported by all of the other Air Force core functions. In the case of the GIISR core function, these relationships could be characterized as “Cyber for ISR” and “ISR from Cyber.”

The “Cyber for ISR” relationship is illustrated by the mission assurance requirement for the cyber domain in support of an ISR mission. Cyberspace mission assurance ensures the availability and defense of a secured network to support a military operation. If the military operation is an ISR mission, the PCPAD component is reliant on a secured cyberspace infrastructure for communication and dissemination. This dependency should define requirements from the GIISR

core function to the Cyberspace Superiority core function. For example, the Air Force currently uses commercial communications segments in some portion of nearly all missions. Short of reconfiguring all communications infrastructure to government-off-the-shelf (GOTS) technology for Air Force missions, this would suggest that requirements for mission resiliency across a hybrid commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS)/GOTS cyber infrastructure in support of ISR missions should be included in a “Cyber for ISR” portfolio planning process—that is, a GIISR CFLI to Cyberspace Superiority CFLI interaction.

Conversely, the “ISR from Cyber” relationship is illustrated by considering how ISR can be executed during cyberspace operations, particularly during cyberspace force application (exploitation). This can be characterized as situational awareness during and in support of cyberspace operations. AFISRA provides all-source cyber-focused ISR including digital network analysis to the 24th Air Force through the 659th ISR Group to enable 24th Air Force operations.23 AFISR’s support includes the following:

1. Current intelligence and reporting,

2. Indications and warning,

3. Threat attribution and characterization,

4. Intelligence preparation of the operational environment, and

5. Computer network exploitation.

Cyberspace ISR requirements are addressed by the Cyberspace Superiority CFLI that, in turn, generates the Cyberspace CFMP. This is another case of ISR requirements being spread across multiple CFLIs. These same ISR requirements could be included in the GIISR CFLI. Cyberspace ISR portfolio planning is part of the 24th Air Force/A2 mission. Although much progress has been made in a relatively short period of time, the 24th Air Force/A2 is still lacking an institutionalized approach to planning and equipping. It is also clear that the required response time for cyberspace ISR capabilities needs to be more rapid than the standard 2-year planning cycle. Moreover, standards and key performance parameters have yet to be identified.24

_______

23USAF. 2010. “Cyberspace Operations. Air Force Doctrine Document 3-12.” Available at http://www.fas.org/irp/DoDdir/usaf/afdd3-12.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2012.

24Col Tom French, Chief of ISR Strategy, Plans and Operations (A2X/O), Headquarters AFSPC. “Evolving Cyberspace ISR Corporate Planning.” Presentation to the committee, December 8, 2011.

Integration of Air Force Core Function Master Plans

From August to October annually, the Air Staff conducts the integration of all 12 CFMPs. In so doing, it produces cross-service core function/portfolio trades as recommendations on current and future capability needs and investments. CFMP integration (also) identifies Program Force Extended (PFE) program candidates for support or adjustment, as it merges individual CFMP planning force proposals into a unified, fiscally constrained planning force that establishes a 20-year major investment plan. The planning force is then published in the APPG.

The next consideration in this discussion is how the ISR CP&A and the CFMP link with PPBE. This should begin with a discussion of how the Air Force organizes itself to produce a balanced, annual input to the DoD budget, which is submitted to the Congress for review, adjustment, approval, and funding. Although the SECAF and CSAF make final decisions about the annual POM submission, they rely on something called the Air Force Corporate Structure (AFCS) to do the work of balancing competing demands and managing resource limitations to produce the right PPBE decisions.

The AFCS has several echelons. At the top is the Air Force Council, which is chaired by the Vice CSAF and consists of three-star Deputy Chiefs of Staff. Below that is the Air Force Board of two-star Air Staff generals, and finally the Air Force Group of one-star generals and colonels. These flag officer bodies are themselves supported in issue formulation by a number of mission and mission-support panels.

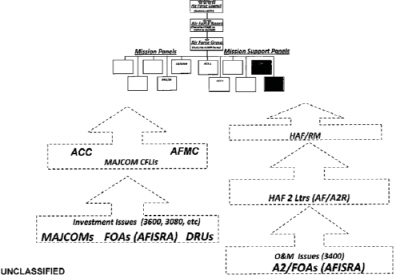

The flow of POM issues to the CFLI process and the AFCS processes begins with calls for issues by the MAJCOMs and AFISRA (see Figure 2-6). Such issues and requirements are received from throughout the AF and HAF and are collected and represented by Capability Advocates, who review the issues and ensure that they are ready to be brought into decision processes of the MAJCOM or AFISRA. The issues are reviewed and validated with a recommended course of action and then prioritized. The panel’s recommendations are then reviewed and validated or modified and then approved by the MAJCOM or AFISRA. The list of approved issues is parsed into investment issues (destined for the CFLI process) and organization and management (O&M) issues (destined for the HAF process).

When the MAJCOM process is complete, the investment issues are forwarded to the appropriate CFLI. The CFLI then takes briefings from knowledgeable staff officers—program element monitors who keep daily track of issues and of available funding for their programs. Issues, with a prioritization and developed course of action, then are to be reviewed by the MAJCOM or AFISRA. Issues and offsets are

FIGURE 2-6 Program Objective Memorandum (POM) issue routing to the Air Force Corporate Structure. NOTE: Acronyms are defined in the list in the front matter. SOURCE: U.S. Air Force.

both considered, as the CFLI has to present a balanced submission to the Air Staff’s AFCS panel responsible for that particular portfolio. The issues are then approved by the CFLI. Once the list is approved, it goes directly to the appropriate Air Staff panel for the beginning of deliberations in the AFCS. Issues are prioritized by AF/ A2 and submitted to Headquarters Air Force Resource Management (HAF/RM). HAF/RM presents a resource balanced portfolio to the Air Staff leadership. It does not necessarily present a portfolio having optimized ISR capabilities. This lack of optimization is generally the result of the need for the Air Force to take from one element, such as an ISR need, in order to pay for a more pressing non-ISR need.

Linkages Between the Air Force and the Intelligence Community

AF/A2 is the focal point for Air Force interaction with the IC. Although the DoD has a rigorous and well-defined process for requirements development, the IC is not monolithic, and its process is by necessity considerably less procedural than that of the DoD. It should also be remembered that although the capabilities developed by the two communities may be similar, their uses and the funding used to procure them are different. Specifically, DoD intelligence systems are funded through the Military Intelligence Program (MIP), whereas national intelligence systems are funded through the National Intelligence Program (NIP). In some cases, MIP funding is transferred to individual intelligence agencies to acquire specific

capabilities. AF/A2 interactions are, therefore, often point-to-point with individual intelligence agencies. Separate offices within intelligence agencies will work with military users, but each agency has a centralized office with responsibility for supporting combatant commanders and military users. The NRO, for instance, has a Directorate for Mission Support that coordinates support and provides deployable teams to various military commands. AF/A2 coordinates individually to determine where there may be synergy and overlap in Air Force and agency investments in ISR capabilities or where data sharing and collaboration may mitigate further service or agency investments.

The Air Force plays an important role in the IC that lies under the purview of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The role of the Air Force in the IC includes the following: (1) weapons systems analysis, particularly air- and air-defense-related all-source analysis, provided by the National Air and Space Intelligence Center; (2) participation in the NSA’s cryptologic activities as a Service Cryptologic Element, accomplished as part of the mission of the Air Force ISR Agency; (3) the acquisition and operation of a variety of national-level ISR capabilities, including Cobra Judy and Cobra Dane, as part of the DNI’s General Defense Intelligence Program; and (4) the articulation by AF/A2 of the value and importance of IC collection against particular potential threats that has led to IC acquisition of the new and successful systems. Moreover, a variety of Air Force reconnaissance platforms, such as U2s, Rivet Joint aircraft, and overhead persistent infrared space-based capabilities, are regularly used to address DNI requirements. Together, these activities involve a significant amount of the Air Force budget and thousands of Air Force personnel, both military and civilian.

Finally, as noted earlier, AF/A2 is the primary interface between the Air Force and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence for planning and funding those ISR capabilities that are part of the NIP. However, NIP-funded programs have been excluded from Air Force Total Obligation Authority (TOA) review. Thus, the Air Force needs increased awareness of what capabilities it provides, along with the IC and other services, to the Joint fight to reduce duplication of effort and funds expended. Given the large amount of resources included in Air Force TOA for national intelligence activities, there should be considerably more attention given to this issue in the Corporate Air Force process beyond AF/A2.

Developing an enterprise approach to ISR investment planning is a difficult and complex challenge, and the Air Force processes that have been put in place to wrestle with this challenge are relatively new and still evolving. As expected with new processes aimed at complex problems, there are deficiencies that need to be addressed.

Finding 2-1. The responsibility for evaluating and informing decisions about Air Force ISR capabilities is diffuse, overly personnel-intensive, and divided among many organizations, resulting in an excessively lengthy process. Specifically, the respective roles and responsibilities of the AF/A2 and the GIISR CFLI are not well defined or well understood, and appear disconnected. Both the ISR CP&A and the CFLI processes have positive aspects, but the processes are immature and insufficiently integrated.

It appears that there are conflicting views held by AF/A2 and the GIISR CFLI regarding roles and responsibilities. The Air Combat Command stressed that the CFLI is charged with producing an annual CFMP and that AF/A2 should only provide Gap Analysis into the CFLI process, which then carries out Solution Analysis. However, the absence of guidance about the relationship between these two organizations has created counterproductive uncertainty. Further, this is exacerbated by frequent changes in process, roles and responsibility, and key personnel.

Finding 2-2. The Air Force ISR planning process lacks adequate process definition and formal interaction between the Space Superiority, Cyberspace Superiority, and GIISR CFLIs. It also does not rigorously integrate ISR contributions from other military services, the IC, and the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Consequently, the Air Force process does not yield ISR investment priorities across domains and security constructs. The Air Force needs increased awareness of what capabilities it provides, along with the IC and other services, to the Joint fight to reduce duplication of effort and funds expended.

Finding 2-3. Air Force platforms do not appear to be included in Air Force cyberspace-related planning processes, even though cyberspace vulnerabilities do exist onboard platforms and in the connectivity between them. Moreover, cyberspace functions can play a very positive role in support of ISR, and ISR systems can help support cyberspace functions. Additionally, the complexity of the multi-organizational relationships involved in current DoD and IC interactions leads to confusion in both execution and planning processes, particularly for cyber operations.

Finding 2-4. The Air Force lacks integrated modeling and simulation and analysis tools that provide traceability from requirements to capability and that conduct operationally relevant ISR trade-space analysis across the DOTMLPFP framework and within and across air, space, and cyberspace domains.

The committee heard about parametric analysis carried out by subject-matter experts. However, the Air Force lacks integrated tools that (1) collaboratively cap-

ture operational shortfalls; (2) prioritize needs; (3) realistically portray existing capabilities; (4) identify funding requirements and potential investment trade-space areas; (5) provide the ability to conduct CFLI-focused and ISR corporate-level “what if/if then” drills to assess operational impact and critical-path CFLI investment areas and flow; and (6) provide the ability to determine and recommend the most suitable course of action to maximize ISR capability (across DOTMLPF-P) for and across each Air Force warfighting domain.

Finding 2-5. The Air Force corporate process “disassembles” the ISR portfolio planning analysis, classifies the elements into isolated, or stovepipe, function components, and then makes trade-offs and/or decisions without the ISR trade-space underpinnings.

Finding 2-6. The ISR CP&A process lacks the ability to respond in a timely way with appropriate fidelity to meet the increasing speed of technology development, operational requirements, and the required decrease in planning-cycle time, particularly in the cyberspace domain.

Finding 2-7. PCPAD is not adequately considered and prioritized by the ISR CP&A process.

Finding 2-8. The ISR CP&A process does not adequately consider affordability in capability trade-space analysis.

Table 2-1 summarizes a set of shortfalls that the committee identified in the Air Force ISR CP&A process, aligned with the findings presented in Chapter 2. The Air Force has made great strides in developing the earlier ISR planning processes (ISR Flight Plan, ISR CP&A, and CFLI/CFMP processes). It is the committee’s view, however, that improvements can be made to achieve greater efficiency in resource utilization, greater effectiveness in the quality of capability solution determination, and more responsiveness in terms of timeliness and in delivering tailored analysis for the mission solution sought.

Over the past few years, the Air Force has made a significant, concerted effort to organize a comprehensive planning process for the Air Force ISR portfolio. The evolution of this planning process began with the ISR Flight Plan, which was rapidly overtaken by the CFLI/CFMP process. The current processes strive to be very inclusive and collaborative, utilizing cross-ISR community subject-matter experts. These processes also include some coordination across relevant CFLIs and

TABLE 2-1 Air Force ISR Capability Planning and Analysis (CP&A) Process Shortfalls and Corresponding Findings

| ISR CP&A Process Shortfalls | Finding |

| Current process does not adequately address all ISR missions, domains of air, space, and cyberspace managed by the Space Superiority, Cyberspace Superiority, and Global Integrated ISR CFLIs, as well as contributions from other military services, the IC, and OSD, and NTISR capabilities. | Findings 2-2 and 2-3 |

| Current process does not provide the ability to analyze investment decisions at different resolutions and timescales. | Finding 2-6 |

| Current process does not support “what if” analyses in well-defined trade spaces. | Findings 2-4 and 2-5 |

| Current process is too air platform-centric and has insufficient focus on PCPAD. | Finding 2-7 |

| Current process does not adequately address affordability, including acquisition and life cycle, as part of capability trade-space analysis. | Finding 2-8 |

| Current process does not provide traceability from requirements to capabilities. | Finding 2-4 |

| Current process is manual and very labor-intensive, resulting in inefficient use of limited resources. | Finding 2-8 |

| Current process is vulnerable to the inevitable changes in Air Force leadership, organization, strategy, and budgets. | Finding 2-1 |

NOTE: Acronyms are defined in the list in the front matter.

associated MAJCOMs. And, as a side product of this effort, a very comprehensive repository of ISR needs, capabilities, and gaps has been developed and is now stored in ISR-CART. Still, a number of improvements can be made to the process itself, the analytical tools, models and simulations that can be applied to the process, the emphasis and inclusion of capabilities from across all domains and architectural elements in the process, and the inclusion of other key decision parameters such as affordability. Such improvements would result in a more efficient and effective process and higher-quality outcomes.

The following chapters examine (1) the corresponding processes used in the other services, the IC, and private-sector organizations, with a view to identifying best practices that could be applied to improve the Air Force ISR CP&A process (Chapter 3); and (2) recommendations for improvements to the Air Force process and a proposed future planning process that addresses the shortfalls identified above (Chapter 4).