3

Extension Services in Fragile Societies

Extension agents working in communities affected by conflict face challenges beyond those normally associated with their jobs. Conflict may have prevented them from acquiring the background, training, or motivation needed to do their job well. They may not have the resources needed to make agricultural improvements. The societal dividing lines created by conflict may limit the cooperative activities on which extension is based.

During the second session of the workshop, three speakers analyzed these challenges and ways of overcoming them. It was clear from these presentations that surmounting barriers to successful extension in fragile societies almost always requires conflict management, which opens multiple routes for peacebuilding tied to extension activities.

CHALLENGES, NEEDS, AND OPPORTUNITIES

Agricultural extension, whether in fragile or secure societies, can be defined as the provision of knowledge to agricultural producers so that they will make a positive change, said Mark Bell, Director of the International Learning Center at the University of California, Davis, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences. This knowledge needs to be credible, as does the person who delivers it. Channels need to be available for the transmission of knowledge both from agents to agricultural producers and from producers

to agents. All these conditions must be met for producers to make positive changes in practice with the information they receive.

With these requisites in mind, Bell analyzed the potential for agricultural extension in fragile societies in terms of challenges, needs, and opportunities.

Challenges

Several challenges are common in developing countries. For example, farmers are innovative and smart, said Bell, but they are not necessarily literate. The literacy rate for males in Afghanistan is about 40 percent, so knowledge often must be conveyed through means other than writing.

In addition, the economics of farming in developing countries poses challenges. Many farmers do not have ready access to credit or agricultural inputs, and the size of their farms is often small. In developed countries, an extension agent can talk to one farmer and have an influence over large areas. In developing countries, the agent must reach many more farmers. In addition, the agricultural infrastructure and markets in developing countries may be less robust than in developed countries.

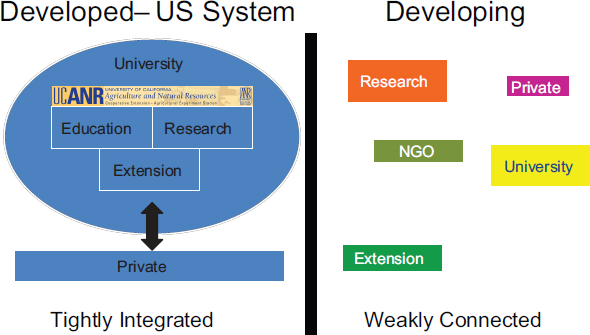

Finally, in developed countries such as the United States, the institutions involved with agriculture and agricultural extension are tightly linked (Figure 3-1). In particular, major components of research, education, and exten-

FIGURE 3-1 In developed countries such as the United States, extension systems are strongly tied to research and education in universities and to the private sector, whereas in developing countries these institutions tend to be largely separated. SOURCE: Bell workshop presentation.

sion are based in universities, which may have strong connections with the private sector. In contrast, linkages are much less strong in developing countries, meaning that institutions work largely in isolation from each other.

Needs

The number one need for successful extension, said Bell, is technical knowledge, which has to be credible and unbiased to win acceptance by agricultural producers. In their role as agricultural experts, extension agents provide farmers with objective, neutral advice based on science.

In addition, in their role as peacebuilders, extension agents must ensure that their activities do not exacerbate conflict. Bell suggested a number of desirable technical and personal skills for extension agents (Box 3-1). Agents also need to have the personal rapport to apply these technical skills in the field.

BOX 3-1

Desirable Skills for Extension Agents

• Team building

• Concept development

• Change management

• Delegation

• Conflict resolution

• Communication

• Planning

• Project management

• Facilitation/mediation

• Priority setting

• Time management

Successful extension activities require participatory approaches, Bell said. Producers have considerable local knowledge that needs to feed in to the extension process, both because of the way this knowledge interacts with the information an extension agent provides and because of the value of this knowledge to other producers.

Extension should take a process-driven approach, according to Bell, in which consideration of audiences and needs leads to solutions, the development of core messages, the delivery of those messages in an accessible form, and evaluation of outcomes. The process should start at the level of the producers rather than through top-down directives.

Finally, institutional elements such as salaries, training, evaluation, and motivating forces are necessary for success. Extension agents need to remain engaged and motivated, despite the institutional fragmentation that is characteristic of many developing countries.

Opportunities

If challenges can be overcome, agricultural extension has the potential to make an important difference in the lives of agricultural producers, their families, and the people who depend on those producers, Bell observed. But he reiterated that extension services will vary depending on local conditions. Extension also needs to draw on a diverse array of potential participants, and their availability will vary from place to place.

Extension services can contribute to peacebuilding, Bell concluded. The simultaneous challenge and opportunity is to bring together people interested in both extension and peacebuilding and build bridges between the two activities.

AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION IN SOUTH SUDAN

Jim Conley, Senior Agriculture Adviser in the Civilian Response Corps of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has been an extension agent in the United States and has worked on reconstruction and stabilization projects in South Sudan, Iraq, and other countries. Most recently, he has been working in South Sudan’s Jonglei State, which is about the size of Pennsylvania. The state has six different tribes, and about 60 indigenous languages are spoken throughout the country. Conflicts are common between farmers and pastoralists and among other competing groups. The major roads in the state are either dirt or gravel and often are impassable during the rainy season.

Conley has had an office in the Ministry of Agriculture and has observed the development of the extension service in Jonglei State. The goal of the state is to have 24 extension officers in each of the state’s 11 counties, which is a large staff for the state. According to Conley, the Ministry of Agriculture has a larger geographic and personnel footprint than any other branch of government.

Extension officers are expected to speak the local language, which usually means that they are from the area. This contrasts with the practice in the United States, where new extension agents typically work in areas other than their local area so that they do not bring preconceptions or biases to

their jobs. In Jonglei State the typical education level of an extension officer is primary or secondary school; very few have university degrees. New extension officers receive three months of intensive training through the NGO Norwegian People’s Aid, with an additional three months of training for those who do well.

Obstacles to Success

Extension services in South Sudan face a number of serious constraints, said Conley. The country has been experiencing open acts of war, which have caused loss of life, property, productivity, opportunity, and social capital. The government’s budget relies heavily on oil, but production was shut down due to conflicts over oil transport. Resources are almost nonexistent, with no money for even basic supplies or technologies. Extension officers include “deadwood” such as men who fought in the army for many years and found nonmilitary jobs with the government; even if these men had agricultural skills in the past, they are likely to have lost them, and most have little familiarity with computers or other technologies. Extension organizations in South Sudan have virtually no academic connection to universities, and any connections that do exist are informal. And extension officers are accountable to the Ministry of Agriculture or to their direct supervisors, Conley said, not to the people they serve, whereas the flow of accountability should run in the opposite direction.

Potential Roles for Extension in Conflict Mitigation

Conley described multiple ways for extension services to contribute to conflict mitigation. Agents can, for example, take steps to promote and reinforce community policing by bringing in experts with the right kind of technical knowledge to foster partnerships for community safety and other safety-enhancing initiatives. They also can spur community and economic development through agricultural and other improvements. And they can catalyze progress on environmental issues, again by bringing in experts who can provide information and engage in dialogue to resolve differences and arrive at solutions.

By way of illustration, Conley cited the Democratic Republic of Congo, where each district by law has a community agriculture council. The extension director is chair of the council, which may include a few other government officials, but most of the council members are farmers. These councils

can guide extension services, much as advisory committees do in the United States. For example, when illegal checkpoints began to appear where fees were extorted from farmers to transport their goods, the community agriculture councils devised a plan for farmers to call someone who could relay the information about illegal checkpoints to law enforcement. Thus the farmers identified a need and the extension service figured out a way to meet that need.

Potential Roles for Extension in Peacebuilding

Agricultural extension in South Sudan could mitigate conflict by contributing to social capital through brokering and bridging functions or by providing early warning of emerging conflict through the assessment and monitoring of developing situations. Agents could provide early warnings about incipient conflicts, serve as honest brokers by providing information or enlisting the help of experts, and work directly with competing groups to resolve conflicts.

All of these options require training in both technical and social skills, and Conley cited several possible models for such training. First, the three months of agricultural training for extension officers could include training in conflict management and group facilitation, perhaps in partnership with an NGO that has experience and expertise in that area. Another useful option would be for the government to have a ministerial specialist in conflict resolution. Alternatively, when extension officers find themselves working on highly politicized topics, they could call in agents from other parts of the country to ensure that the extension system remains neutral.

In rural communities, much agricultural work is done by women, who Conley said have made some strides especially in improving their status working with local and international NGOS. In fact, he surmised that an extension system with peacebuilding as a component would hold more promise if it engaged rural women specifically.

Other local capacity should also be tapped. An example of how to cultivate and apply local skills and expertise, Conley said, is the Barefoot College, an NGO in India that uses local knowledge to make rural communities self-sustaining through development activities owned and managed by those in the community itself.

South Sudan has strengths, Conley observed: an energized youth who are eager to contribute to the country, people returning to the country who want the nation to succeed, and a growing emphasis on women’s empower-

ment. With sufficient training and resources, extension services could draw on these and other strengths to play a substantial role in peacebuilding in South Sudan, he concluded.

AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION IN IRAQ

David Nisbet, Supervisory Microbiologist at the USDA Agricultural Research Service, described his experience as an agricultural adviser on a provincial reconstruction team in Iraq. He worked in Karbala Province on the western bank of the Euphrates River in a region of great conflict, where the convoys in which he traveled were often attacked. It was not a matter of Sunni–Shiite fighting but rather of intertribal competition for resources in the province.

At first local officials in the province would not interact with Nisbet, partly because of the failure of a promised transnational water pipeline project. Eventually he was able to make contact with the agricultural extension service in the province, and he found the people there to be well educated and sophisticated. The director of the office, in particular, was very effective in working across tribes and was committed to the community.

The province had a very active vegetable farming industry, and the extension office was working hard to deliver new technologies to farmers. Surprisingly, given the socially conservative society, the extension agents aggressively recruited women to the programs. In fact, Nisbet said, it was quite likely that the programs focusing on women were among the more effective that the agency funded. But Nisbet characterized the level of the technology as comparable to that of 1950s American agriculture, and resources were not available to make needed improvements.

Unintended Consequences of Good Intentions

Nisbet cautioned that efforts by outside groups to prepare extension personnel to undertake peacebuilding activities may not be appropriate or accepted in areas of conflict. In such situations, participating locals in positions of authority have to be excellent politicians, as was true of the agricultural extension officer with whom Nisbet interacted who did not become a victim of the violence gripping the country. Others were not so fortunate. Another extension agent with whom Nisbet worked disappeared for six weeks because he had been working closely with the United States, and women with whom the United States was working were beaten.

Good intentions can have other unintended consequences, Nisbet said. Iraqis did not necessarily see themselves as involved in a conflict until they became involved with the United States. He reported that the people with whom he worked would have left Iraq if they could, because essentially they became mice in a cat-and-mouse game.

In addition, large quantities of money were misspent. One of his major accomplishments, Nisbet said, was to block the development of a large poultry industry, which would immediately have failed in the 125° heat of Iraq’s summers.

Potential Roles for Agricultural Extension

Agricultural extension in Karbala Province could have a huge role, said Nisbet, by making the province into an exporter of agricultural products. To be effective in improving either agriculture or peacebuilding efforts, extension officers need training, Nisbet stated—not necessarily in the United States, but perhaps in neighboring countries where they could learn what would work effectively in Iraq. Finally, the agricultural sector needs 21st century technology if it is to achieve its potential.

The discussion following these presentations revolved around the broad subjects of roles, metrics, and motivation.

Fred Tipson, Special Adviser at USIP, commented on advantages and considerations related to the many different roles of an extension agent. For example, someone from outside a community may not be connected to local disputes. In some places, an extension agent may serve as a community organizer, whereas in other places that role would be inappropriate or perhaps even dangerous. Different roles call for different skills—whether those of a diplomat, technologist, or anthropologist—and will also be influenced by the partnerships that often are required to create change. For example, a major challenge can be getting local agricultural producers to work with an extension agent, and different approaches may be more—or less—effective in different settings for achieving that end.

Nisbet reiterated the potential role of extension personnel as sentinels for local developments, whether related to agriculture or other activities. Agents can convey information to appropriate institutions for action without being seen as personally responsible for the action.

Jacqueline Wilson, Senior Program Officer at USIP, observed that extension personnel should be “connectors”—for example, connecting people with knowledge to people with the leverage to get things done. As a specific example, people in the community may be excellent agriculturalists—as Judith Payne, e-Business Adviser at USAID, observed—and extension agents should tap into their expertise. Agents also can convene parties with diverse interests in searching for common ground.

Montague Demment, Associate Vice President, International Development, for the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, called attention to the difficulty of developing metrics to assess the value of investments in both agricultural extension and peacebuilding. Services provided by the public sector can be particularly difficult to measure, even though they may have substantial long-term benefits. Furthermore, peacebuilding and extension both compete with other public services, requiring that value be attached to each. As a further complication to the measurement of value, as Unruh pointed out, circumstances and needs may change rapidly—from survival to crisis management to recovery to stability—requiring a continually morphing set of services rather than adherence to a strict model.

Kevin Brownawell, Interagency Professional in Residence at USIP, observed that Bell’s definition of extension—providing knowledge to farmers so they can make positive change—also can be usefully applied to the role of extension in peacebuilding. In the context of peacebuilding, providing knowledge is more feasible than solving problems. Similarly, referring individuals to other institutions is more viable than an individual attempting to serve in the role of an institution.

Finally, Dale Johnson, Principal Agent and Extension Specialist at the Western Maryland Research and Education Center, emphasized the importance of commitment, motivation, and adequate resources. Without motivation, an extension agent cannot be effective. And without the funds to travel to farmers or even to make telephone calls, agents cannot do their jobs. Money needs to be specifically available for these activities rather than being allocated entirely to salaries.

This page intentionally left blank.