Access to Care for Substance Use Disorders

A review of access to care for substance use disorders (SUDs) was a central component of two tasks in the committee’s

- a comparison of the adequacy of the availability of and access to care for SUDs for members of the active duty and reserve components of the armed forces; and

- an assessment of the adequacy of the availability of and access to care for SUDs for dependents of members of the armed forces, whether such dependents suffer from their own SUD or because of the SUD of a member of the armed forces.

To address these tasks, this chapter begins by defining access to care for SUDs and providing a framework for the ensuing analysis. Subsequent sections examine the availability of care, policies and other factors that affect access to care, and data on utilization of care. The chapter concludes with findings based on this analysis. The committee’s analysis considers the direct care system (military treatment facilities), the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), and the system for purchase of care (TRICARE). It reviews access to SUD care for active duty personnel; military dependents; and, to the extent data were available, members of the National Guard and Reserves. The assessment examines each branch of the military where sufficient detail was available.

The armed forces focus on maintaining warrior fitness and promoting resilience among service members and military families. Active duty personnel experience frequent mobilizations, difficult transitions, combat situations, and an operational tempo with long and multiple periods away from their families and supports. The physical and emotional stressors experienced by many military women and men may contribute to an increase in their use of alcohol and other drugs. Access to substance use services—from prevention to a wide spectrum of interventions for substance misuse and abuse—can help military personnel and their families maintain psychological resilience and fitness. Access to routine screening, confidential brief education, brief counseling, brief interventions for those with emerging substance use problems, and more intensive treatment for those with SUDs promotes good health and may reduce the current high rates of alcohol and prescription drug misuse. If these services are delivered without sanctions or stigma, they promote an effective response to emerging alcohol and other drug use problems, and foster a system in which individuals seek help rather than hide problems.

The committee’s framework for assessing access to SUD care is based on its view that alcohol and other drug use behaviors exist on a continuum, and that certain patterns of alcohol and other drug use place some individuals at high risk of developing medical and social problems and possibly abuse or dependence. The discussion here focuses on the use of legal substances (i.e., alcohol, controlled substances prescribed by a clinician) since the use of illicit substances (when detected) prompts separation proceedings.

Addressing access to brief intervention and treatment for alcohol and other drug use is a complex undertaking. Access includes both the availability of services and the use of appropriate modalities and types of services at the appropriate times. As described in Chapter 5, contemporary substance use treatment systems include frequent screening, brief counseling, brief interventions in primary care settings, a focus on client-centered motivational interviewing, multiple entry points to treatment, pharmacotherapies that reduce cravings and maintain functioning, outpatient counseling, intensive outpatient programs, residential treatment when needed, and continuous contact with counseling professionals after an intense period of treatment. Modalities of care utilize evidence-based environmental, psychosocial, and medication interventions. The standard of practice in modern SUD treatment no longer relies on inpatient hospital services, except for the most medically complex patients. Continuity and duration of ambulatory services are more important than the provision of care in residential settings (IOM, 2006).

Aday and Andersen (1974) developed a health services framework with which to examine access to medical treatment. Subsequent investigators modified this framework to assess access to services for alcohol and other drug use disorders (Hser et al., 1997; Weisner and Matzger, 2002; Weisner and Schmidt, 2001). The Aday and Andersen (1974) model addresses barriers and facilitators to access using three domains: (1) predisposing, (2) enabling, and (3) need. The predisposing domain consists of individual and social facilitators and barriers. Individual factors are intrinsic characteristics that describe the propensity of individuals to use health services. Social factors include marital status, family, and social networks; these are the social contextual characteristics that influence treatment seeking. In the substance abuse field, social networks are distinguished by whether they include individuals who are influences for not using versus using substances, as well as treatment seeking versus nonseeking. The enabling domain consists of structural/financial and environmental factors. Structural/financial facilitators are similar to those for general health care and include the supply and availability of treatment and the types of treatment and medications available. The need domain includes the severity of alcohol and other drug use and comorbid mental health or medical problems.

Barriers to Access in the Military

Barriers to accessing care for SUDs can be environmental, structural, social, and/or cultural. Environmental factors, such as pressure or mandates to enter treatment, sanctions, perceptions about the effectiveness of treatment, and stigma, are unique to the behavioral health field, particularly the addiction field, and more apparent in the military than the civilian sector. Civilian individuals frequently enter SUD treatment as a result of legal, welfare, employment, or family pressures or even mandates (Weisner, 1990). The same is true in the military; most service members are assessed for the need for treatment only after receiving sanctions for a substance-related incident (e.g., driving under the influence [DUI], assault) or other drug-related infraction (e.g., possession of an illegal substance) or upon having their substance use discovered through random drug testing. Thus, the most important structural factors in the military are (1) policies that treat alcohol misuse and other drug use as a discipline problem, (2) heavy reliance on deterrence (i.e., random drug testing) as the prevention approach, and (3) the lack of a standard medical protocol for early identification and brief intervention before a disciplinary infraction occurs.

While many predisposing and need-related facilitators of and barriers to treatment in the military are similar to those in the civilian sector, some structural and environmental barriers are unique to the military—notably, policies and practices that result in random drug testing as a primary

pathway to obtaining substance use services. First, random drug testing technology is not applicable to alcohol or to designer drugs not yet classified as illicit (e.g., Spice, bath salts). Second, civilian best practice addresses unhealthy substance use as a preventable and treatable health problem with known risk factors and offers screening and interventions as part of primary care services early and confidentially. Military practices, however, focus on abuse and dependence and view alcohol and other drug misuse as violations of the code of conduct and/or as criminal activities (e.g., DUI, drug possession). The emergence of unhealthy use before a negative incident occurs generally goes unnoticed or is ignored by medical programs, and while policy describes the need for prevention programs (see Chapter 6), the vast majority of resources are used for random drug testing.

The lack of distinction between unbecoming conduct and a medical problem creates an environment in which engaging in substance use treatment has counterproductive implications. Receiving treatment, even when treatment causes the desired change in behavior, is perceived as resulting in a negative career trajectory. Consequently, active duty service members (ADSMs) are not highly motivated to enter treatment. This can have the unanticipated effect on public safety of having service members continue to perform critical tasks without having had their problems treated. Indeed, during its information gathering meetings and site visits, the committee heard from military treatment professionals that many service members perceive alcohol treatment as a threat to their military career and consequently avoid it.1 The vignette in Box 7-1 describes an extreme, but not isolated, case in which early intervention with a soldier could have occurred. A random drug test in 2007 identified cocaine use, but 15 subsequent tests were negative. In 2011, the soldier self-enrolled in an Army Substance Abuse Program (ASAP), fully 8 years after a problem was first indicated.

In keeping with the military’s occupational health model, policy DODI 1010.6 requires that a service member’s commander be notified of and involved in treatment for an SUD (DoD, 1985, 5.2.2.2.3) (see also Chapter 6). This policy applies whether the soldier self-refers, is referred by a medical provider, or is referred by the commander, and regardless of whether an alcohol-related incident or positive drug test is involved. Branch policies impose similar requirements. For example, the Army policy for self-referral states:

The ASAP counselor will contact the unit commander and coordinate the Soldier’s formal referral using DA Form 8003, which will be signed by the

____________________

1 Personal communication, Vladimir Nacev, Ph.D., Resilience and Prevention Directorate Defense Centers of Excellence, and Col. John J. Stasinos, M.D., Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, May 4, 2011.

BOX 7-1

A Soldier’s Untreated Substance Abuse

A soldier tested positive for cocaine use in March 2007. He was not required to enroll in an Army Substance Abuse Program (ASAP), and a Department of the Army (DA) Form 4833 was never completed. Despite 15 negative urinalyses from October 2008 to January 2011, the soldier self-enrolled in ASAP during the latter month for cocaine abuse and marijuana and alcohol dependence. He was apprehended in July 2011 for assault consummated by a battery (domestic violence). A review of law enforcement databases revealed that these offenses were not the beginning of the soldier’s high-risk behavior; he had been arrested for criminal trespass, marijuana possession, and evading arrest in 2003—3 years prior to his delayed-entry report date of August 2006. While driving on an interstate highway in November 2011, the soldier collided with another vehicle, killing himself and two others instantly and injuring two others. He had been driving the wrong way on the highway for 2 miles at the time of the accident. While drug and toxicology results are unknown at this time, packets of Spice were found in the soldier’s vehicle.

SOURCE: U.S. Army, 2012a, p. 30.

unit commander and be annotated as a self referral. The commander will be a part of the rehabilitation program and, as a member of the Rehabilitation Team, will be directly involved in the decision of whether rehabilitation is required. (U.S. Army, 2009, p. 49)

These policies are necessary to ensure that service members are medically ready for deployment. Yet in current practice, the lack of confidential treatment even for problems that do not meet symptom criteria for substance abuse or dependence has the perverse effect of leaving many treatable problems undetected and unaddressed. As a consequence, several Army reviews have identified a high proportion of suicides, other deaths, and other negative consequences associated with untreated SUDs (U.S. Army, 2010, 2012a).

Historically, military policy has not addressed unhealthy alcohol use or reliance on prescribed medications that places service members at high risk for SUDs and later disciplinary problems. The military now has programs that provide screening and early intervention for depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) within primary care settings to reduce the stigma associated with seeking treatment for these conditions, but it has not

adopted similar early-intervention, best-practice models for discussion of emerging alcohol and other drug use problems. In civilian model programs, early intervention for problem alcohol and other drug use is available in medical care settings such as primary care and emergency rooms. A new DoD policy, DODI 64990.08, may permit further development of brief interventions in military health care settings for service members at risk of alcohol use problems.

Military culture also creates unique environmental barriers to accessing care for SUDs. First, there are few to no public health interventions targeting the medical consequences of heavy drinking. Military personnel are warned of the severe sanctions for alcohol or other substance use that results in a formal consequence (e.g., DUI); the message conveyed, however, is that heavy drinking is acceptable, while getting into trouble because of the behavior is not (Burnett-Zeigler et al., 2011; Gibbs et al., 2011; Skidmore and Roy, 2011). Second, alcohol and other drugs often are misused as coping mechanisms for combat and other stress and hence recognized on a continuum of medical problems (Stokes et al., 2003), yet many service members are treated for long periods of time with opioid pain medications and with controlled drugs to treat anxiety and sleep disorders. These high prescribing rates introduce opportunities for abuse and addiction. The epidemiological data reviewed in Chapter 2 suggest that abuse of prescribed medications used to treat pain and/or sleep disorders is growing.

While tracking of medications dispensed to individuals in theater is problematic (Defense Health Board, 2011), recent changes have been made to prescribing practices for certain controlled medications. For instance, ALARACT (All Army Activities) 062/2011 (U.S. Army Surgeon General, 2011) requires an expiration date on prescribed opioid medications. However, the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) Formulary still permits the dispensing of 180 days of certain controlled substances for personnel who are deployed to war zones (DoD, 2012). These prescribing practices are intended to address the potential lack of access to medications currently being taken by the service member in a deployed environment. Yet these practices may contribute to physical dependence on such medications in several ways—being given for a longer duration than is clinically prudent, given without close medical supervision, and given to service members who have alcohol or other substance use problems. The Army has made recent policy changes aimed at reducing the prescribing of medications with the potential for abuse and addiction (U.S. Army, 2012b; U.S. Army Surgeon General, 2011). As discussed in Chapter 6, DoD instated stricter limits on the length of prescription for controlled drugs in May 2012 (see Finding 6-1).

In both civilian and military populations, a frequently cited barrier to seeking treatment for SUDs is denial of the need for treatment among

those who need it (SAMHSA, 2011). Respondents to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health described their problem as not severe enough to require treatment and said that drug use helped them cope with difficult emotional stimuli. Among military personnel returning from Iraq and Afghanistan stigma was the most frequently cited reason for not seeking treatment for combat-related mental health conditions, including substance use (Dickstein et al., 2010; Hoge et al., 2004; Stecker et al., 2007). Self-stigma was particularly poignant; it is difficult for military personnel to identify themselves as being in need. In the civilian sector, one role for brief advice from a clinician to patients is to address their perception of their need for treatment and the value of the available treatment, but this function currently does not exist in the military.

Role of Primary Care and Medical Treatment

The military’s medical care model for first-line treatment of behavioral health problems that are commonly comorbid with SUDs (e.g., PTSD, depression, suicidal ideation and attempts) now relies heavily on detection and treatment in primary care. Screening for behavioral health conditions, including hazardous alcohol use, occurs routinely in primary care. As discussed in Chapter 5, evidence-based approaches of brief advice, early intervention, and referral to treatment when needed through models commonly known as screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) should be a focus of the full continuum of care. Medical protocols for SBIRT, however, have not been implemented in military primary care programs. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, in contrast, routinely screens for alcohol use problems and offers brief intervention and referral to further treatment if needed. As discussed in Chapter 6, the screening and brief intervention elements of the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Substance Use Disorders (VA and DoD, 2009) have not been implemented in the Military Health System. Primary care also is the setting in which pharmaceutical therapy for SUDs often takes place in the commercial sector. The lack of primary care protocols in the military (and policy restrictions on the use of some of these effective medication therapies) is an additional barrier to accessing SUD care and is inconsistent with the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline (VA and DoD, 2009). Consequently, primary care is the single largest missed opportunity in the military for early and confidential identification of alcohol and other drug misuse. DoD and branch policies and practices currently do not provide for early and confidential interventions for alcohol and other drug misuse. The committee perceives this to be a tremendous barrier to service members’ accessing SUD care.

CARE AVAILABILITY, ACCESS, AND UTILIZATION IN THE DIRECT CARE SYSTEM

DoD policy requires the armed services to provide alcohol and drug abuse prevention and treatment services for active duty personnel as part of medical readiness and risk reduction programs (DoD, 1997). The committee’s analysis of access to and utilization of SUD care is organized by branch and includes a review of the size of the population addressed, the number of SUD programs available, and the data on utilization of services. The content of these programs is described in Chapter 6 and Appendix D, and the SUD workforce is described in Chapter 8. This section concludes with a brief review of DoD-wide programs that may enhance access to SUD care.

There is no uniform DoD reporting system for monitoring the number of detected alcohol incidents or drug-positive events, the number of referrals for assessment or treatment, or the number enrolled in direct care treatment programs. In response to queries from the committee, each branch provided data using its own definitions, formats, and level of detail. In its site visits, the committee learned that program directors at installations can query their own systems, but do not have access to system-wide data for judging overall trends or monitoring the transfer of patients from one military installation to another. The committee does not know how any methodological differences in data reporting among branches or components affected the information provided for this study.

One major challenge confronting all branches with respect to access to SUD care is that troops are dispersed across the United States, abroad in permanent stations on U.S. territories (e.g., Guam), and in foreign nations (e.g., Japan, Germany). Family members also reside with troops where there are permanent stations. Thus, access to SUD care for these troops and family members may require travel to obtain the appropriate level of clinical care. The capacity for integrated behavioral health services in areas outside the continental United States may be particularly important when SUD programs are not available.

Air Force

The Air Force provides SUD services through 75 Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment (ADAPT) programs, one at each military treatment facility, with nearly 400 counselors. None of these programs offer inpatient, medically supervised treatment or residential, medically monitored treatment. The Air Force has one ADAPT program that provides intensive outpatient care at Andrews Air Force Base. The Air Force Medical Operations Agency reported to the committee that during fiscal year (FY) 2010, 736 service members self-referred to ADAPT, and 4,644 members

TABLE 7-1 Utilization of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment (ADAPT) Services by Active Duty Air Force Personnel *

| FY 2006 | FY 2007 | FY 2008 | FY 2009 | FY 2010 |

| 1,559 | 1,429 | 1,532 | 1,565 | 1,454 |

*Includes 11-26 persons treated annually who were activated National Guard/Reserve members.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Lt. Col. Mark Oordt, Air Force Medical Operations Agency, October 25, 2011.

were referred by Command.2 Beyond self-referrals and Command referrals, individuals can be referred to ADAPT by medical providers, but these represent the smallest proportion of referrals. Table 7-1 displays the number of active duty patients enrolled in treatment at ADAPT clinics from FY 2006 to FY 2010. Comparing the number of self- and Command referrals in FY 2010 (5,380) with the number of patients enrolled in treatment in the same period (1,454) suggests that most referrals do not lead to enrollment in treatment. As described in Chapter 6, most individuals receiving services through ADAPT do not meet diagnostic criteria for enrollment in formal treatment and instead are enrolled in alcohol brief counseling as an indicated prevention measure. The number treated has not increased over time and was lower in FY 2010 than in 3 of the 4 prior years.

Army

ASAPs are located within the Army Installation Management Command (IMCOM) as part of the human resources program (see also Chapter 6). The Army has 38 ASAPs, which typically offer American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Level I (outpatient service) care to military personnel and have insufficient capacity to serve family members with SUDs.3 Army regulations require all ASAP counselors to have a master’s or doctoral degree in psychology or social work. The ASAP counselors may be uniquely positioned to provide integrated care for service members with SUDs and comorbid mental health problems, but are credentialed only to treat SUDs and are not authorized to treat mental health problems. Military personnel who require partial hospitalization or inpatient care or have a dual diagnosis often are referred by Command to the civilian provider network. The extent to which ASAP programs are available to Army personnel

____________________

2 Personal communication, Lt. Col. Mark Oordt, Air Force Medical Operations Agency, October 25, 2011.

3 Personal communication, Les McFarling, Ph.D., Army Center for Substance Abuse Programs, March 30, 2011.

and family members permanently stationed abroad or in states and territories outside the continental United States is unclear.

The TRICARE Management Activity (TMA) Section 596 report indicated that the Army operates only one inpatient (around-the-clock), medically monitored treatment program, which has 20 inpatient beds (DoD, 2011b, p. 30). During a site visit to Fort Belvoir Community Hospital (see Appendix A for the committee’s site visit agenda), the committee learned of a newly opened residential treatment center (ASAM Level III rehabilitation program for SUDs under the Army’s Medical Command). This medical service will provide care for ADSMs from all branches of the military and eligible retirees. When referred by Command, personnel may be treated in any SUD facility under a budget agreement with the military treatment facility commander; that is, commanders are not restricted to the use of TRICARE network Substance Use Disorder Rehabilitation Facilities (SUDRFs) (SUDRFs are discussed later in the purchased care section).4

With regard to in-theater care, a report of the Army Inspector General concludes that there is a lack of compliance with Army alcohol and other drug use policy when units are in a combat operation environment (U.S. Army, 2008). CENTCOM General Order #1 states that alcohol consumption and possession and drug use are illegal in the combat environment (United States Central Command, 2006). AR 600-85 requires that deployed commanders maintain a drug deterrence program. However, the Inspector General’s report finds little compliance with these directives and notes that DoD provides no guidance on how to implement the policies and no professional staff to implement them and monitor compliance, and that the rotation of personnel in and out of the combat environment inhibits enforcement. In efforts to deter drug use during deployment, the Army updated AR 600-85 in 2009 to include new language meant to increase random drug testing in theater. To increase access to screening and treatment in theater, the Army is in the first phase of rolling out an Expeditionary Substance Abuse Program to provide SUD services during deployment, primarily through telephone contact with in-theater providers.5

Table 7-2 shows data on initial referrals of Army ADSMs to ASAP for FY 2006-2010. The Army Center for Substance Abuse Programs (ACSAP) reported to the committee that for FY 2010, 3,401 distinct active duty individuals enrolled in treatment as self-referrals, and 10,968 enrolled because of Command referral.6 ACSAP provided detailed information on

____________________

4 Personal communication, John Sparks, TRICARE Regional Office-West, March 18, 2012.

5 Personal communication, Col. John J. Stasinos, M.D., Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, March 15, 2012.

6 Personal communication, Les McFarling, Ph.D., Army Center for Substance Abuse Programs, January 13, 2012.

TABLE 7-2 Army Active Duty Initial Referrals to the Army Substance Abuse Program (ASAP)

| FY 2006 | FY 2007 | FY 2008 | FY 2009 | FY 2010 | |

| Inirial Referrals | 16,826 | 18,164 | 20,316 | 23,044 | 23,093 |

SOURCE: Personal communication, Les McFarling, Ph.D., Army Center for Substance Abuse Programs, January 13, 2012.

gender, rank, and substance of initial referral (not treatment enrollment) for 23,093 individuals in FY 2010. According to a recent Army analysis (U.S. Army, 2012a), 52 percent of soldiers referred to treatment for either alcohol or other drug problems enrolled in outpatient treatment. Many who are referred to ASAP for assessment fail to meet diagnostic criteria for SUDs and are enrolled in the Army’s indicated prevention course Prime for Life (described in Appendix D). When soldiers are enrolled in treatment at ASAP, they do not always complete the program for various reasons (e.g., deployments). The rates of successful completion of rehabilitation from FY 2001 to FY 2010 averaged 66 percent for alcohol and 47 percent for other drugs (U.S. Army, 2012a).

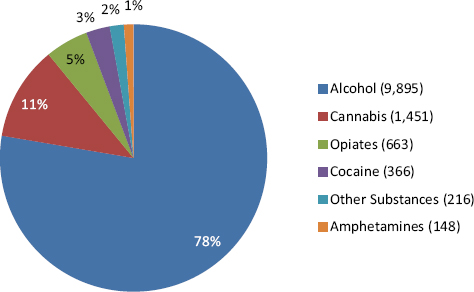

The committee also received data on treatment enrollment in ASAP. Figure 7-1 shows the data received on the distribution of enrollment ranked

SOURCE: Personal communication, Les McFarling, Ph.D., Army Center for Substance Abuse Programs, March 30, 2011.

by type of substance in FY 2010. Alcohol misuse is the single largest reason for enrollment, followed by use of cannabis and opiates.

According to data for FY 2006-2010, women averaged about 10 percent of initial referrals to ASAP, but this proportion declined during the period from 11.2 percent to 9.8 percent. Officers represented only 2.5 percent of total initial referrals in FY 2010, but the number of officer referrals increased by 63 percent between FY 2006 and FY 2010. In FY 2010, alcohol accounted for 75 percent of initial ASAP referrals (n = 17,343/23,093), cannabis for 12.5 percent, opioids for 4.3 percent, cocaine for 3.0 percent, and all other substances for under 2 percent each. Opioid referrals grew from 238 in FY 2006 to 992 in 2010, an increase of more than 300 percent, while alcohol referrals and total referrals grew by around 36 percent. The total number of referrals to ASAP in FY 2008-2010 was about 37 percent higher than in FY 2006-2007.

ACSAP also provided counts of drug positives and alcohol violations as indicators of the need for SUD care for FY 2010. The number of persons testing positive for nonprescription illicit drugs was 6,597 (7.7 percent women), for prescription drugs was 1,363 (8.1 percent women), with a DUI charge was 4,609 (5.4 percent women), and with another alcohol-related charge was 3,439 (8.0 percent women).7 If these counts represented distinct individuals, the sum would be 16,008 Army men and women with detected alcohol or other drug use, a number smaller than the total number of ASAP referrals (23,093). Undoubtedly, however, some individuals are double counted across classes of drug positives and alcohol violations, so the detected need would sum to fewer than 16,008 distinct individuals. Nonetheless, the number of persons with detected alcohol violations and other drug use is undoubtedly much smaller than the total need for care.

Military personnel assigned to Warrior Transition Units (WTUs) have an elevated risk for SUDs, making access to SUD care an important priority for this population. The Department of the Army established the Warrior Transition Command, which manages care for 18,000 soldiers and veterans annually. Army staff includes nearly 4,000 squad leaders, platoon sergeants, nurse case managers, and other support staff who coordinate care in WTUs and community-based WTUs (U.S. Army, 2011). On a site visit to Dewitt Army Hospital, the committee learned of a newly opened comorbid disorders program located within the Warrior Transition Brigade at Fort Belvoir. This program was designed to provide treatment for soldiers with complex mental health needs. For the committee’s review and assessment of this program, see Appendix D.

____________________

7 Personal communication, Les McFarling, Ph.D., Army Center for Substance Abuse Programs, January 13, 2012.

Navy

The Navy operates 38 Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Programs (SARPs), including 35 outpatient-only programs (in Bahrain, Guam, Italy, Japan, and Spain) and 3 U.S.-based SARPs that provide intensive inpatient care (34 days of around-the-clock counseling and rehabilitation services) (DoD, 2011b, p. 30). The largest SARPs are based at San Diego, California, and Norfolk, Virginia. The three SARPs that provide outpatient, intensive outpatient/partial hospitalization, and residential/inpatient care treat patients with comorbid disorders. All SARP patients participate in continuing care following discharge through the Navy’s My Ongoing Recovery Experience (MORE) program, a Web-based and telephone program contracted through Hazelden that provides continuing care and support services to patients leaving treatment at a SARP. Marines treated at Navy SARPs may also enroll in the Navy MORE program.

The Navy Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program Office reported to the committee that 4,566 Navy patients and 5,535 Marines were treated at Navy SARPs in 2010, and 625 of the Navy patients were self-referrals.8Table 7-3 displays the number of active duty Navy and Marine personnel who were enrolled in treatment at SARPs for FY 2006 through FY 2010 (Marines also are treated in the Service Academy Career Conference [SACC] program, described in the next section). The number of Navy service members treated declined by 2 percent over the period (Marine utilization statistics are discussed in the next section). Nearly all Navy members were treated for alcohol use disorders, as indicated by the substance recorded at initial referral (data not shown). No other drug (opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, cannabis) was responsible for more than 17 treatment admissions in 2010, and “other drugs” accounted for a total of 71 treatment admissions. The number of Navy members receiving services for alcohol and cocaine use declined over the period, while the number for other drug types increased. Women increased as a percentage of Navy members with alcohol use disorders from 8 percent to 11 percent in the period FY 2006 to FY 2010, and Navy officers represented 3 percent of those receiving alcohol services in FY 2010.

The Navy also provided counts of drug positives and alcohol violations as indicators of the need for SUD care for FY 2010. The number of persons testing positive for nonprescription illicit drugs was 1,492 (11.1 percent women), for prescription drugs was 292 (11.3 percent women), with a DUI charge was 1,416 (women 6.9 percent), and with another alcohol-related charge was 2,489 (8.2 percent women). In contrast with the Army,

____________________

8 Personal communication, George Aukerman, Navy Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention Office, February 15, 2012.

| FY 2006 | FY 2007 | FY 2008 | FY 2009 | FY 2010 | |

| Navy | 4,677 | 4,482 | 4,076 | 4,617 | 4,566 |

| Marines | 3,033 | 2,781 | 3,402 | 4,683 | 5,535 |

| Total SARP | 7,710 | 7,263 | 7,478 | 9,300 | 10,101 |

| % Marines | 39.3 | 38.3 | 45.5 | 50.4 | 54.8 |

SOURCE: Personal communication, George Aukerman, Navy Alcohol and Drug Abuse Prevention Office, February 15, 2012.

the number of Navy service members needing services for drugs other than alcohol appears to be much smaller than the number identified through drug-positive tests. The number needing services for alcohol appears to be slightly higher than the number with alcohol violations, even if no individuals were counted with both DUI and other alcohol-related charges.

Marine Corps

SACCs are located at 15 Marine installations and are under the direction and authority of the Personnel Command. Of the 15 SACCs, 14 provide outpatient treatment, and 12 provide intensive outpatient treatment. The Marine Corps reported that it attempts to have one counselor for every 2,500 active duty Marines.9 The Marine and Family Programs Division reported utilization statistics to the committee from the Alcohol and Drug Management Information Tracking System (ADMITS). Of those Marines admitted into substance abuse treatment in FY 2011, 354 self-referred to a SACC, and 2,463 were referred by Command.9Table 7-4 displays the total number of active duty Marines who were screened at a SACC, the number that completed the early intervention program (Impact, which is described in Appendix D), and the number that completed outpatient or intensive outpatient treatment provided at a SACC. It is unclear whether the number completing treatment represents the total utilization of SACCs or only those who completed the full treatment course. In the past 5 years, no dependents have been treated at SACCs. Based on information for 2010, the SACCS provided services to 67 percent of persons assessed for treatment need, assuming that the number receiving early intervention does not duplicate any of those completing outpatient or inpatient treatment (Table 7-3). Most of the SACCS have the capacity to provide intensive outpatient services; the service counts provided by the Marine Corps combine intensive and regular outpatient services.

____________________

9 Personal communication, Eric Hollins, Marine and Family Programs Division, October 25, 2011.

| FY 2006 | FY 2007 | FY 2008 | FY 2009 | FY 2010 | |

| Number of Marines screened | 7,710 | 5,794 | 6,965 | 6,709 | 7,201 |

| Completed early intervention | 2,714 | 3,289 | 3,255 | 2,974 | 2,677 |

| Completed outpatient or intensive outpatient treatment | 2,144 | 2,873 | 2,224 | 1,974 | 2,204 |

SOURCE: Personal communication, Eric Hollins, Marine and Family Programs Division, October 25, 2011.

As discussed earlier, Marines also access care at Navy SARPs if they need higher levels of care than the SACCs offer or if a SACC program is not available at their duty location; Marines’ utilization of services at SARPs was presented previously in Table 7-3. In 2010, 5,535 Marines were served by SARPs, a number that increased by 82 percent between FY 2006 and FY 2010. For fully 84 percent of those who accessed services at SARPs, alcohol was reported as the drug of initial referral in 2010. In contrast with the Navy, a substantial number of Marines were treated for use of cannabis (n = 305), opiates (82), cocaine (80), amphetamines (113), and other drugs (312), and admissions for all drugs including alcohol, except cocaine, increased substantially from FY 2006 to FY 2010 (data not shown). When Marines receive services at Navy SARPs, they often are stepping up or down from care provided at their local SACC; therefore, the numbers of Marines receiving services at SACCs and SARPs do not represent distinct individuals.

SUD Care Accessed by Dependents at Military Treatment Facilities

To understand the extent to which family members of ADSMs access SUD care at military treatment facilities, the committee reviewed data provided by TMA. Table 7-5 presents the numbers and rates10 of dependents of ADSMs receiving SUD care at military treatment facilities. The utilization data are based on diagnosis (excluding nicotine) and may include stays for detoxification only. These data demonstrate that it is rare for dependents of ADSMs to receive SUD care in military treatment facilities. Utilization of SUD care in the purchased care sector by dependents of ADSMs is discussed later in this chapter.

The committee also received information on direct care services for all ADSMs and active duty family members (ADFMs) with an SUD diagnosis,

____________________

10 See Table 7-8 for the total average number of beneficiaries by region, which was used to calculate rates.

| West (Nper 1,000) | North (Nper 1,000) | South (Nper 1,000) | |

| Active Duty Family Member (ADFM) Adult Dependent Beneficiaries (ages 18 and over) | |||

| Alcohol diagnoses | 317 (1.0) | 249 (0.8) | 483 (1.7) |

| Other drug diagnoses | 325 (1.0) | 267 (0.8) | 508 (1.8) |

| Both alcohol and other drug diagnoses | 23 (0.1) | 9 (0.0) | 30 (0.1) |

| ADFM Child Dependent Beneficiaries (ages 14–17) | |||

| Alcohol diagnoses | 11 (0.2) | 9 (0.1) | 35 (0.5) |

| Other drug diagnoses | 70 (1.2) | 39 (0.6) | 78 (1.2) |

| Both alcohol and other drug diagnoses | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) |

SOURCE: Personal communication, Frank Lee, TRICARE Management Activity, March 2, 2012.

combined across branches. These data for FY 2010 show the relative reliance on different service modalities (detoxification, emergency, inpatient, and outpatient) at military treatment facilities and are summarized in Table 7-6. It should be noted that some portion of the outpatient services was not for SUD treatment but for ancillary services associated with the other three categories, as evidenced by the settings of care listed in the footnote to the table. In other words, it would be incorrect to assume that 54,043 ADSMs received outpatient counseling for SUDs, as some of the

| Type of Care | ADSM (Nper 1,000) | ADFM (18 and over) (Nper 1,000) | ADFM (14–17) (Nper 1,000) |

| Detoxification | 661 (0.4) | 16 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Emergency | 2,815 (1.9) | 677 (0.7) | 83 (0.4) |

| Inpatient | 1,845 (1.2) | 192 (0.2) | 9 (0.0) |

| Outpatient* | 54,043 (35.5) | 2,347 (2.6) | 207(1.1) |

*Outpatient care includes care provided in any of the following settings: emergency roomhospital, hospital-outpatient, office, ambulance-land, independent laboratory, psychiatric facility (partial hospitalization), community mental health center, nonresidential substance abuse treatment facility, other unlisted facility, urgent care facility, home, public health clinic, rural health clinic, ambulatory surgical center, nursing facility, comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facility, federally qualified health center, group home, ambulance-air or water, Indian Health Service freestanding facility, prison/correctional facility, assisted living facility, military treatment facility, independent clinic.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Greg Woskow, TRICARE Management Activity, June 8, 2012.

outpatient services counted may have been associated with and already counted under detoxification, emergency department, and inpatient care.

DoD-Wide Programs

DoD contracts for programs to expand ready access to behavioral health services and encourage help seeking among military personnel and their dependents. Some of these programs, such as Military OneSource and the Yellow Ribbon Campaign, are described in Appendix D. These programs generally provide nonmedical support services and are considered an important pathway to SUD care and other services. Box 7-2 describes these programs. The committee did not receive data on the volume of calls, consultations, or referrals provided. A recent RAND report found that many of these programs do not track outcome data and have largely not been evaluated (Weinick et al., 2011).

Summary of Access in the Direct Care System

The Air Force and Navy reported serving fewer individuals in their SUD programs in FY 2010 than in most prior years. In contrast, the Army and Marine Corps reported increased treatment admissions. No branch had high rates of self-referral to treatment, a finding consistent with the literature reviewed and reports provided to the committee regarding the perceived stigma of receiving treatment. The Army reported the highest proportion of self-referrals, which likely is due to the Confidential Alcohol Treatment and Education Pilot (CATEP) program (described in Appendix D) and contributed to higher than average utilization rates.

The committee identified a number of aspects of the organization of care, policies on and barriers to care, and other differences in how service members gain access to care that appear to contribute to some of this variation. The branches are remarkably diverse in the types of SUD programs they offer and the pathways to care they provide. Despite a far greater number of troops relative to other branches, the Army operates ASAPs at only 38 locations and acknowledges it has been trying to expand its numbers of licensed social workers and psychologists. Many Army installations have no ASAP, and the Army operates only one 20-bed medically monitored inpatient unit for SUD care. In contrast, the Navy operates 38 SARP outpatient programs, including 5 programs in foreign countries and 3 SARP inpatient/outpatient hospital units. SARPs actually provide services to more Marine Corps than Navy patients even though the number of Navy service members far exceeds the number of Marines. The Navy’s SARP integrates care for comorbid mental health issues and is managed by Medical Command. The Marine SACCs are at 15 installations, and nearly

| Military OneSource | Offers nonclinical counseling free of charge to active duty, Reserve, and National Guard service members and their families. Does not report to military commanders. |

| Military Pathways | Provides free and anonymous self-assessments online and over the telephone, with the goal of reducing stigma, raising awareness, and encouraging referrals to DoD or VA services. |

| Military Family Life Consultants | Invited by commanders to specific military installations with impending deployment or return of troops. The contractor provides licensed mental health professionals who offer confidential nonclinical counseling outside of the health care system, with no documentation in the medical record being required. |

| Defense Center of Excellence Outreach Center | Provides 24/7 behavioral health support for a range of psychological health needs and traumatic brain injury. |

| Yellow Ribbon Program | Offers reintegration events hosted by National Guard units at 30, 60, and 90 days after return. Guard members, Reservists, and family members receive information on, among other things, accessing services for medical, mental health, and substance abuse problems. Military family life consultants may be invited as a resource. |

all offer both intensive and regular outpatient services, unlike the facilities of the other branches. The worldwide geographic distribution of service members may also explain some of the variation in SUD care. All branches cannot feasibly operate and staff specialty SUD programs in all locations. In the United States, the military can supplement its direct care SUD programs with purchased services offered by local VHA programs or TRICARE providers (discussed below). These options do not exist, by and large, for the numerous service members and family members who are stationed overseas or on ships or submarines or are deployed.

The committee’s ability to make direct comparisons across branches or even within branches across years was hampered because of variations in the way data on SUD care are maintained and reported. These variations were magnified when the committee attempted to integrate direct care information with data from the TRICARE regional offices and purchased care programs. This exercise illustrated the complex nature of obtaining and reviewing data on the scope of the SUD problem DoD-wide and understanding the full extent of services offered to address alcohol and other drug problems, both emerging and chronic. The lack of consistent reporting of data DoD-wide appears to hamper monitoring of how well current programs meet the needs of the armed forces. At its various site visits, the committee learned that different systems store different types of data. Program managers must therefore consult multiple systems (typically at least one managed by Installation Command and one managed by Medical Command, and sometimes more) either weekly or daily to monitor the progress from positive drug tests to Command referrals to substance use assessment.

CARE AVAILABILITY, ACCESS, AND UTILIZATION IN THE VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

The VHA also provides SUD services for ADSMs, and the committee reviewed the access standards for SUD care specified in Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics (VHA Handbook 1160.01) (VA, 2008). These standards are consistent with the National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Treatment of Substance Use Conditions endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF, 2007) and with the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Substance Use Disorders (VA and DoD, 2009). Box 7-3 lists the services that must be readily available, according to the access standards, to all patients when clinically indicated.

Currently, the VA provides care for SUDs in 108 intensive outpatient clinics, 237 residential rehabilitation treatment programs (8,443 operational beds), and 63 programs with specialty SUD bed sections (1,658 beds). The Opioid Treatment Program includes 32 in-house and 22 contracted off-site formally approved and regulated opioid treatment clinics using methadone or buprenorphine as agonist medications. Office-based buprenorphine treatment is offered by “waivered” physicians in nonspecialty settings (e.g., primary care), including 132 medical centers and 109 community clinics. The VA provides an SUD-PTSD specialist funded at each facility to promote integrated care. These specialists provide treatment based on the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Substance Use Disorders (VA and DoD, 2009) and its counterpart for PTSD

BOX 7-3

Access Standards of the Veterans Health

Administration for SUD Care

Treatment Modalities

- Pharmacotherapy and psychosocial interventions are important treatment options for veterans with SUDs.

- Regardless of the particular intervention chosen, motivational interviewing style must be used during therapeutic encounters with patients, and the common elements of effective interventions must be emphasized.

Screening and Brief Intervention

- At least annual screening must be provided across settings for alcohol misuse and tobacco use.

- Targeted case finding must be conducted for use of illicit drugs or misuse of prescription or over-the-counter agents.

- Further assessments must be performed to determine the level of misuse and to establish a diagnosis.

- Referral to treatment must be offered for those with dependence.

- All providers must systematically promote the initiation of treatment and ongoing engagement in care for patients with SUDs.

Other Program Standards

- Appointments for follow-up treatment must be provided within 1 week of completion of medically supervised withdrawal management.

(VA and DoD, 2010).11 A recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) (2011b) study concluded that in general, the VA service delivery system is comprehensive, but the actual provision of specialty services varies among VA facilities. Starting in 2004, VA medical facilities became authorized TRICARE providers and expanded the SUD continuum of care available to certain ADSMs living near one of these facilities (DoD, 2011b). TMA reported to the committee, however, that few ADSMs accessed VA treatment through TRICARE during 2011 (West Region = 15, North Region = 77, and South Region = 18).12

As members of the National Guard and Reserves are not eligible for direct care unless activated (i.e., placed on federal orders for deployment

____________________

11 Personal communication, Daniel Kivlahan, Department of Veterans Affairs, November 16, 2011.

12 Personal communication, Frank Lee, TRICARE Management Activity, March 2, 2012.

- Intensive substance use treatment programs must be available for all veterans who require them to establish early remission from an SUD.

- Multiple (at least two) empirically validated psychosocial interventions must be available for all patients with SUDs who need them, whether psychosocial intervention is the primary treatment or an adjunctive component of a coordinated program that includes pharmacotherapy.

- Pharmacotherapy with approved, appropriately regulated opioid agonists (e.g., buprenorphine or methadone) must be available to all patients diagnosed with opioid dependence for whom it is indicated and for whom there are no medical contraindications in addition to, and directly linked with, psychosocial treatment and support.

- If agonist treatment is contraindicated or not acceptable, antagonist medication (e.g., naltrexone) must be available and considered for use when needed.

- Patients with an SUD must be offered long-term management for that disorder and any other coexisting psychiatric and general medical conditions. The patient’s condition must be monitored in an ongoing manner, and care must be modified, as appropriate, in response to changes in the patient’s clinical status.

SOURCE: VHA Handbook 1160.01 (VA, 2008).

or another contingency order), VA health care is a relatively new source of care for these personnel returning from deployments to Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) (38 U.S.C. § 1710[a], 38 CFR §§ 17.36, 17.38 [2009]). ADSMs discharged from service also have new eligibility. Specifically, this recent policy change states that

any veteran who has served in a combat theater after November 11, 1998, including OEF/OIF veterans, and who was discharged or released from active service on or after January 28, 2003, has up to 5 years from the date of the veteran’s most recent discharge or release from active duty service to enroll in VA’s health care system and receive VA health care services.13

____________________

13 National Defense Authorization Act of 2008, Public Law 110-181, 110th Congress (January 28, 2008).

The nature of the need and demand for SUD treatment may differ for reserve and active duty component service members, although their role in the recent conflicts has been equally prominent. Reserve component citizen soldiers may transition repeatedly throughout their military career from active duty to civilian status. The Guard and Reserve forces are recognized as indispensable and integral parts of the nation’s defense. In the Army, in particular, the total size of the reserve component was approximately equal to that of the active duty component in FY 2010-2011, and in recent history, its size exceeded that of the active duty component (see Chapter 2).

A GAO (2011b) analysis examined mental health services in the VHA system and utilization of the services among OEF/OIF veterans. GAO estimated that there are 2.6 million living veterans from the OEF/OIF era (12 percent of all living veterans). OIF/OEF veterans accounted for 12 percent (n = 139,167) of veterans who received mental health services in FY 2010 and 10 percent (n = 36,797) of veterans treated for an SUD.14 Thus, among VA recipients of SUD services, OIF/OEF veterans’ use of mental health services is high; OEF/OIF veterans receive mental health care at a higher rate (38 percent) than all other veterans (28 percent) (GAO, 2011b).

The VHA provided the utilization data presented in Table 7-7. VA SUD services are offered in both specialty and primary care settings. The patient numbers shown in Table 7-7 are for veterans, including members of the National Guard and Reserves who have been demobilized from active duty but not released from service; in other words, they may be called to another deployment and return to active duty status. The percent change in diagnosed individuals over the last four quarters shows a clear increase in incidence. Table 7-8 presents data on VA SUD services provided to OEF/OIF/Operation New Dawn (OND) veterans, separating out care provided to those who were ADSMs and those who were members of the National Guard and Reserves in FY 2006-2010. The 4.6-fold increase in numbers treated for SUDs during the 5-year reporting period suggests that the VA has become an important source of SUD treatment services for the armed forces.

CARE AVAILABILITY, ACCESS, AND UTILIZATION IN THE PURCHASED CARE SYSTEM

Under the TRICARE insurance plans, network and non-network providers deliver services for SUD care in civilian-operated settings (purchased

____________________

14 A veteran was counted as having a mental health condition if, at any point in the fiscal year, his or her medical record indicated at least two outpatient encounters with any mental health diagnosis (with at least one encounter having a primary mental health diagnosis) or an inpatient stay in which the veteran had any mental health diagnosis.

| Number (Cumulative from 1st Quarter FY 2002) | % Change Over Most Recent 4 Quarters for Which Data Are Available | |

|

Total OIF/OEF/OND patients with behavioral health disorder |

404,060 | |

|

Alcohol abuse (ICD 305.0) |

49,793 | 26.6 |

|

Alcohol dependence syndrome (ICD 303) |

46,753 | 29.8 |

|

Nonalcohol abuse of drugs (ICD 305.2-9) |

32,908 | 33.7 |

|

Drug dependence (ICD 304) |

24,550 | 34.7 |

NOTE: ICD = International Classification of Diseases.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Daniel Kivlahan, Department of Veterans Affairs, July 3, 2012.

TABLE 7-8 Number of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)/Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF)/Operation New Dawn (OND) Veterans Treated in Department of Veterans Affairs Programs for an SUD Diagnosis*

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Active duty | 4,696 | 8,272 | 13,249 | 19,950 | 26,440 |

| Guard/Reserves | 4,423 | 6,594 | 9,576 | 12,860 | 16,058 |

| Total | 9,119 | 14,866 | 22,825 | 32,810 | 42,498 |

*Analysis includes OEF/OIF/OND veterans who accessed the VHA for an inpatient stay or outpatient encounter and had a primary and/or secondary SUD diagnosis.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Barbara Swailes, Department of Veterans Affairs, March 9, 2012.

care) (see Chapter 3). These purchased care settings extend the capability of the Military Health System to treat ADSMs with SUDs and also are reimbursed under the TRICARE benefit for services to ADFMs, retirees and their family members, and certain other civilians.

TRICARE Benefits and Access Standards

The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 32 199.4 specifies the required TRICARE benefits for SUD care, including emergency and inpatient hospital care for complications of alcohol and drug dependency.15 In contrast

____________________

15 Title 32: National Defense. Part 199: Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services (CHAMPUS): Basic Program Benefits. 32 C.F.R. § 199.4 (June 27, 2012).

with commercial managed care contracts, TRICARE contractors are not required to have specific SUD care capabilities within their networks.16 The level of care within a network generally includes detoxification, hospitalization, and partial rehabilitation, and regulations permit detoxification and rehabilitation care with limits. In contrast with the commercial sector, intensive outpatient programs are not a designated level of care in the TRICARE SUD benefit, although commanders have the discretion to purchase such care on a case-by-case basis (TMA, 2008). Also unlike the commercial sector, TRICARE does not reimburse for office-based individual counseling for an SUD unless it is comorbid with a mental health disorder that is the primary diagnosis. TRICARE benefit limits for SUD care are summarized in Box 7-4. These benefit limits are inconsistent both with current standards of care for SUDs based on recent legislation requiring parity of mental health and substance abuse care and other medical services and with requirements in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (as discussed in Chapter 4). The benefit coverage for pharmaceutical therapy for SUDs is limited to anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and naltrexone during alcohol detoxification and rehabilitation. While opioid detoxification may employ buprenorphine or naloxone, the medications are not covered as maintenance therapies.

The policies that govern access to SUD care (Box 7-4) are described in Chapter 7 of the TRICARE Operations Manual (TMA, 2008). Regulations require that all SUD services, including outpatient services, be delivered by an SUDRF. An SUDRF is defined as a Joint Commission–accredited hospital that offers an SUD program or a freestanding Joint Commission–accredited facility. To obtain the designation of an SUDRF, these facilities must be certified as such by KePRO, the quality monitoring contractor for TRICARE (KePRO, 2011). KePRO publishes a monthly listing of all certified mental health facilities on its website; as of June 2012, the listing included just 20 freestanding SUDRFs across the United States with current certification. According to a 2007 report of the DoD Task Force on Mental Health, “38 states have no approved substance abuse residential facility including heavily populous states (e.g., New York, Ohio, Illinois) and states with a large military presence (e.g., Washington, Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, DC)” (DoD, 2007, p. 51). On KePRO’s June 2012 mental health facility listing, the only state to have gained an SUDRF since that report was released is Virginia, which now has two such facilities. As a result of the restriction of care to such facilities, SUD services for TRICARE beneficiaries are available neither through most community-based addiction treatment centers nor through licensed independent practitioners who are not affiliated with an SUDRF.

____________________

16 Personal communication, John Sparks, TRICARE Regional Office-West, July 19, 2011.

BOX 7-4

TRICARE Policies Governing Access to SUD Care

- Must be obtained in an authorized Substance Use Disorder Rehabilitation Facility (SUDRF).

- For outpatient care in an SUDRF, up to 60 visits are allowed per benefit period; however, office-based individual counseling is limited to cases in which the primary diagnosis is a mental disorder and the SUD a comorbidity.

- Alcohol/chemical dependency counselors are the only category of providers specifically licensed for substance abuse treatment. Alcohol/chemical dependency counselors are not among the “qualified mental health providers” reimbursed by TRICARE.

- Residential (inpatient or partial day)—up to 21 days and 7 days for detoxification.

- Family therapy—up to 15 visits per benefit period.

- Restricted to three treatment benefit episodes in a lifetime (defined as 365 days after the first service regardless of the care used). Emergency department or hospital care is not counted as the start of an episode.

- Coverage is specifically allowed for antabuse, but not for the use of certain medically assisted treatments, including methadone and buprenorphine, as a maintenance program.

SOURCE: TRICARE Operations Manual (TMA, 2008, Chapter 7).

The TRICARE Operations Manual (TMA, 2008, Chapter 7, section 3) describes the reimbursement and cost sharing for TRICARE beneficiaries (these policies govern medical and behavioral health care generally and are not specific to SUDs). Reimbursement rates can become a barrier to access when they are out of line with rates paid by the majority of health plans. The committee heard testimony that the TRICARE rate-setting method leads to unacceptably low rates for some SUDRFs, diminishing access to care.17 The TRICARE maximum allowable payment to providers is set equal to the Medicare payment rate. A 2009 reimbursement rate study, not specific to SUDRFs, examined 13 medical specialties, including psychiatry and psychology. Commercial rates were found to be higher than TRICARE reimbursement rates for these specialties in almost all of the geographic market areas analyzed, implying that a facility would be less willing to take

____________________

17 Personal communication, John Sparks, TRICARE Regional Office-West, February 2, 2012.

a new TRICARE patient than a commercially insured patient when space was available (Kennell et al., 2009).

Population at Risk and Utilization of SUD Care

Table 7-9 shows the mean number of beneficiaries by region eligible for care through the TRICARE network. These numbers provide a basis for estimating the total population of beneficiaries eligible for care. Table 7-10 presents the number and rate per 1,000 of beneficiaries receiving SUD care in the purchased care sector (based on diagnosis rather than setting of

TABLE 7-9 Average Number of Beneficiaries by TRICARE Region for Fiscal Year 2010*

| West | North | South | |

| Active duty service members | 548,086 | 532,163 | 440,337 |

| Active duty family members (ADFMs), aged 18 and over | 320,446 | 318,528 | 278,445 |

| ADFMs, aged 14 to 17 | 59,634 | 68,854 | 64,573 |

*Computed as monthly average enrollment in TRICARE Prime across FY 2010.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Frank Lee, TRICARE Management Activity, March 2, 2012.

| West (Nper 1,000) | North (Nper 1,000) | South (Nper 1,000) | |

| Active Duty Service Member Beneficiariesa | |||

| Alcohol diagnoses | 2,443 (4.5) | 1,924(3.6) | 1,808 (4.1) |

| Other drug diagnoses | 676 (1.2) | 875 (1.6) | 715 (1.6) |

| Both alcohol and other drug diagnoses | 137 (0.2) | 160 (0.3) | 154 (0.3) |

| Active Duty Family Member (ADFM) Adult Dependent Beneficiariesb (aged 18 and over) | |||

| Alcohol diagnoses | 1,075 (3.3) | 1,252 (3.9) | 924 (3.3) |

| Other drug diagnoses | 980 (3.0) | 1,640(5.1) | 1,135 (4.0) |

| Both alcohol and other drug diagnoses | 133 (0.4) | 158 (0.5) | 117(0.4) |

| ADFM Child Dependent Beneficiariesb (aged 14–17) | |||

| Alcohol diagnoses | 177 (2.9) | 153 (2.2) | 79 (1.2) |

| Other drug diagnoses | 283 (4.7) | 312 (4.4) | 220 (3.3) |

| Both alcohol and other drug diagnoses | 39 (0.6) | 20 (0.3) | 5 (0.1) |

aMay include a small number of reserve component members enrolled in TRICARE Reserve Select or with transitional benefits.

bMay include a small number of dependents of reserve component members enrolled in TRICARE Reserve Select or with transitional benefits.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Greg Woskow, TRICARE Management Activity, May 7, 2012.

care) in each region. The utilization data are based on diagnosis (excluding nicotine) and may include stays for detoxification only. In Table 7-9, the total served includes detoxification services, counseling, and rehabilitation in SUDRFs and outside of SUDRFs in network and non-network purchased care facilities. The overall rate of receiving SUD care per 1,000 beneficiaries for adult ADFMs is small in each region when summed across alcohol and other drugs, ranging from 6.7 per 1,000 beneficiaries in the West Region to 9.5 in the North. In the North and South Regions, the number of adults treated for other drug diagnoses exceeds the number treated for alcohol diagnoses. In contrast with adult ADFMs, the utilization rate for ADFM children in the West Region (7.6 per 1,000 beneficiaries) is higher than that in the other regions; all regions had more child beneficiaries receiving services for other drugs than for alcohol.

In all regions, the greatest number of ADSMs received services for an alcohol diagnosis. The rate ranges from 3.6 to 4.5 per 1,000 ADSM beneficiaries. The rate of purchased care services for other drug disorders is very low (1.2-1.6 per 1,000 ADSM beneficiaries). Note that these services are in addition to those of direct care providers; however, it is unknown whether these ADSM individuals were also served by the military program (e.g., for outpatient care or aftercare) and already counted under direct care, or are distinct individuals. Branch policies permit commanders to refer their ADSMs to SUD services that cannot be provided in the direct care system. The TRICARE regional offices assist military commanders in finding the care that is needed. It is unknown whether the ADSMs who received SUD services in these purchased care settings received any coordination of their treatment plan or aftercare by a branch military program as well. It is possible that some of these individuals were at installations without SUD programs.

Table 7-11 presents TRICARE data for FY 2010 on the total days’ supply and total number of users of pharmacological SUD treatments for adult ADSMs and ADFMs being treated for alcohol or other drug use disorders. Chapter 5 describes the evidence for use of these medications as best practice for addiction care, and the use of pharmacological treatment is also recommended by the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Substance Use Disorders (VA and DoD, 2009). In Table 7-11, each medication category includes the total number of individuals who received the medications from military treatment facility, retail, and mail order pharmacies; there may be some duplication across those three categories if an individual filled prescriptions for these medications via multiple pharmacy systems. Additionally, the number of individuals who received pharmacological treatment are not distinct across the medication categories, so some individuals who received multiple medications throughout the course of treatment would be represented multiple times. Therefore,

| Active Duty Service Members | Active Duty Family Members | |||

| Medication | Sum of Days’ Supply | No. of Users | Sum of Days’ Supply | No. of Users |

| Antabuse | 35,560 | 605 | 14,127 | 214 |

| Buprenorphine | 35,966 | 405 | 60,718 | 668 |

| Campral | 30,024 | 619 | 21,736 | 343 |

| Methadone | 250 | 6 | 1,405 | 20 |

| Naltrexone | 54,057 | 1,034 | 26,518 | 371 |

| Vivitrol | 956 | 14 | 270 | 3 |

SOURCE: Personal communication, Greg Woskow, TRICARE Management Activity, May 7, 2012.

the actual number of distinct individuals who received pharmacological treatment is lower than the counts shown.

As the table shows, the single most common medication prescribed for SUD care was naltrexone, with 1,034 ADSM users and 371 ADFM users. The long-acting form of naltrexone (vivitrol) was rarely prescribed, and medications for treatment of opioid addiction (buprenorphine, methadone) were prescribed for only a small number of users, presumably for detoxification as maintenance on these medications is not a covered benefit. When one compares the number of ADSMs diagnosed with alcohol use disorders in Table 7-10 (6,175) with the number who received either naltrexone (1,034, some of which would have been prescribed for alcohol dependence, but some for opioid dependence), antabuse (605), and camparal (619), it is clear that many individuals with alcohol use disorders did not receive medication therapy. Among those diagnosed with drug use disorders (2,900), only 400 were prescribed buprenorphine. It is apparent that the use of these medications is not an integral part of SUD treatment for most individuals despite the evidence for their effectiveness.

Tables 7-12 through 7-15 summarize SUD services by type of facility for the TRICARE North, West, and South Regions. These data were provided by each regional office and thus provide different levels of detail. The committee requested data that were based on analyses of primary SUD diagnoses (excluding nicotine-only diagnoses). Thus, settings that delivered detoxification services or emergency department services associated with alcohol or other drug intoxication would be counted.

Table 7-12 presents the total number of ADSM and ADFM users of SUD care in the purchased care North Region by type of facility and whether the facilities participated in the TRICARE network. These data show that an equal number of ADSMs were treated in network and non-network

| Setting | Active Duty Service Members | Active Duty Family Members (Adult and Child) |

| Network freestanding SUDRF | 688 | 359 |

| Network hospital-based SUDRF | 552 | 234 |

| SUDRF Total | 1,240 (50%) | 593 (36%) |

| Non-network provider | 557 | 494 |

| Other network provider | 685 | 574 |

| Non-SUDRF Total | 1,242 (50%) | 1,068 (64%) |

NOTE: SUDRF = Substance Use Disorder Rehabilitation Facility.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Marie L. Mentor, TRICARE Management Activity, February 27, 2012.

SUD facilities, and that many more ADFMs were treated in non-network than in network facilities. From these data, it is clear that ADSM beneficiaries were equally likely to receive some alcohol or other drug care in non-SUDRF facilities and SUDRFs, and that ADFM beneficiaries were more likely to receive care in non-SUDRF facilities. Non-SUDRF facilities include hospitals that offer SUD care but do not have certification from KePRO as an SUDRF. Of beneficiaries who received care from a SUDRF, 40 percent or more received it in a hospital-based rather than a freestanding facility.

Table 7-13 presents the total numbers of ADSMs, ADFM spouses, and ADFM children receiving inpatient and outpatient SUD care in the West Region in both network and non-network facilities. These data demonstrate that among all beneficiary groups, the vast majority received inpatient rather than outpatient services. The West Region had a different pattern from the North Region in that the majority of SUD care was provided in network facilities.

Table 7-14 presents the number of ADSM, ADFM adult, and ADFM child beneficiaries receiving SUD care in freestanding or hospital SUDRFs. The South Region data suggest there is some capacity to treat child dependents for SUD care in that network. The majority of care again was provided in hospital-based rather than freestanding SUDRFs.

To examine further what types of care are being provided in different settings, the committee reviewed additional data from TMA on the numbers of beneficiaries whose claims were selected based on diagnosis and classified by setting as detoxification, emergency, inpatient, and outpatient service for SUDs. Table 7-15 displays the services associated with an SUD diagnosis provided in purchased care settings, along with the rates of use

| Setting | Active Duty Service Members | Active Duty Family Members (Aged 18 and Over) | Active Duty Family Members (Aged 14–17) |

| Inpatient: non-network | 238 | 148 | 15 |

| Inpatient: network | 852 | 465 | 55 |

| Total Inpatient | 1,090(80%) | 613 (90.5%) | 70(98.6%) |

| Outpatient: non-network | 59 | 8 | 0 |

| Outpatient: network | 214 | 56 | 1 |

| Total Outpatient | 273 (20%) | 64 (9.5%) | 1 (1.4%) |

| Totals | 1,363 | 677 | 71 |

| Network total | 1,066 (78.2%) | 156 (23.0%) | 56 (78.9%)a |

| Non-network total | 297 (21.8%) | 521 (77.0%) | 15(21.1%)b |

aAll but one are inpatient.

bAll are inpatient.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Frank Lee, TRICARE Management Activity, March 2, 2012.

| Setting | Active Duty Service Members | Active Duty Family Members (Aged 18 and Over) | Active Duty Family Members (Aged 14–17) |

| Freestanding SUDRF | 283 (20.4%) | 186 (30.8%) | 53 (36.6%) |

| Inpatient other network | 1,102(79.6%) | 417 (69.2%) | 92 (63.4%) |

| Total | 1,385 | 603 | 145 |

NOTE: SUDRF = Substance Use Disorder Rehabilitation Facility.

SOURCE: Personal communication, Frank Lee, TRICARE Management Activity, March 2, 2012.

per 1,000 beneficiaries. Note that Table 7-6 presented earlier in the section on direct care and Table 7-15 may include some duplication if beneficiaries had claims for care in both military treatment facilities and purchased care settings during the year. Table 7-6 also shows that the rate of use of direct care for ADFMs was very low—well under 1 per 1,000 beneficiaries—in all settings but outpatient care and for both adult and child dependents. Furthermore, the outpatient setting includes, to an unknown extent, ancillary services associated with detoxification, emergency, or inpatient care (as indicated by the footnote to Table 7-6); thus the 2,347 adults and 207 youth may not all have received outpatient counseling services. It is clear that military treatment facilities have limited capacity to provide SUD services

| Type of Care | Active Duty Service Members (n per 1,000) | Active Duty Family Members (Aged 18 and Over) (n per 1,000) | Active Duty Family Members (Aged 14–17) (n per 1,000) |

| Detoxification | |||

| Institutional SUDRF | 229 (0.2) | 192 (0.2) | 4 (0.02) |

| Professional SUDRF | 293 (0.2) | 313 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other setting | 1,269 (0.8) | 897(1.0) | 21 (0.1) |

| Emergency | |||

| Institutional SUDRF | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Professional SUDRF | 34 (0.02) | 49 (0.05) | 5 (0.02) |

| Other setting | 2,752(1.8) | 2,796 (3.0) | 411 (2.1) |

| Inpatient | |||

| Institutional SUDRF | 413 (0.3) | 260 (0.3) | 7 (0.03) |

| Professional SUDRF | 52 (0.03) | 62 (0.1) | 3 (0.02) |

| Other setting | 3,235 (2.1) | 1,834 (2.0) | 212(1.1) |

| Outpatient* | |||

| Institutional SUDRF | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Professional SUDRF | 1,208 (0.8) | 563 (0.6) | 68 (0.4) |

| Other setting | 7,716 (5.1) | 6,160 (6.7) | 1,025 (5.3) |

NOTE: SUDRF = substance use disorder rehabilitation facility.

*Outpatient care includes care provided in any of the following settings: emergency roomhospital, hospital-outpatient, office, ambulance-land, independent laboratory, psychiatric facility (partial hospitalization), community mental health center, nonresidential substance abuse treatment facility, other unlisted facility, urgent care facility, home, public health clinic, ruralc health clinic, ambulatory surgical center, nursing facility, comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facility, federally qualified health center, group home, ambulance-air or water, Indian Health Service freestanding facility, prison/correctional facility, assisted living facility, military treatment facility, independent clinic.

for ADFMs—hence the importance of the TRICARE purchased care program. This implies that family members who receive the bulk of their primary care at a military treatment facility may experience some challenges in having their SUD care integrated with the rest of the care they receive.

The committee received information that the institutional SUDRFs represented in Table 7-15 included hospital-based programs only. The definition of a professional SUDRF the committee received was that it represented a professional service claim emanating from an SUDRF; the committee presumed this denoted outpatient counseling or services within the hospital-based setting for an individual not admitted for overnight care. The committee was told the data system did not permit separate identification of SUDRF overnight or professional services in freestanding facilities.

While the definition of these settings is unclear, the table supports the finding that few individuals received SUD care in the purchased care system. This finding is not surprising for ADSMs given that in most circumstances, they have access to outpatient services at their military treatment facility and potentially to other levels of care if transferred to inpatient programs offered by the larger installations. As noted in Table 7-6, however, typically fewer than 1 per 1,000 ADFMs received SUD care at military treatment facilities. Combined with the low utilization rates in Table 7-15, these data are evidence that ADFMs face strong barriers to gaining access to SUD care in the military treatment facility and purchased care systems combined.

Data in Table 7-15 on the treatment of SUDs in purchased care facilities further demonstrate that network facilities do not provide all the SUD care received by ADFMs. In part, this reflects the finding that non-SUDRF hospitals are used for emergency detoxification and withdrawal from substances. Nevertheless, these data also show that the majority of inpatient SUD care was delivered outside of SUDRFs. The majority of outpatient services were received from settings other than professional SUDRFs. However, some of these outpatient services may represent not counseling services but claims for ancillary services associated with other types of care.