Understanding Substance Use Disorders in the Military

Substance use and abuse has long been a concern for the nation, both in and out of the workplace (IOM, 1994), with consequences that include lost productivity, disease, and premature death. Indeed, it has been estimated that more than one in four deaths in the United States each year can be attributed to the use of alcohol, illicit drugs, or tobacco (Horgan et al., 2001). Thus, it is no surprise that substance abuse is a significant issue for the U.S. military.

This chapter provides essential background information on substance use disorders (SUDs) in the military. It begins with a summary of our current understanding of SUDs, the scope of the problem in the military, and the development of military substance abuse policy. The chapter then details the composition and sociodemographic characteristics of the armed services as context for a discussion of the prevalence of substance use in the military. Next is a review of the health care burden of SUDs in the armed services, followed by the description of a conceptual approach to prevention, intervention, and treatment of alcohol use problems—the substance use concern of greatest significance for the military. The final section presents a summary.

UNDERSTANDING SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

The classification system of the current (fourth) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) includes two possible diagnoses for SUDs: abuse and dependence. In 2013, however, a fifth edition (DSM-5)

will replace this classification to reflect the recent scientific literature. A catch-all diagnosis of “substance use disorder” will replace the “abuse” and “dependence” diagnoses, and its severity will be rated according to the number of symptoms of compulsive drug-seeking behavior. Thus, alcoholism will become “alcohol use disorder,” and services based on the diagnosis of “dependence” versus “abuse” will have to be redefined. The symptoms as described in DSM-IV will remain the same except that “legal problems” has been eliminated as a symptom, and “craving” has been added as a symptom (APA, 2011). Several papers have analyzed the proposed criterion changes and demonstrate support for the new classification in DSM-5 (Hasin, 2012). The prevalence of SUDs will not be significantly affected by this change.

The modern approach to SUDs begins with prevention that involves educating the population in the avoidance of risky behaviors and establishing and enforcing policies to discourage such behaviors. One such behavior is binge drinking, defined as five or more standard drinks on a single occasion for a male or four or more for a female (NIAAA, 2005). This is a common behavior among young adults, whether in the military or not, and it increases the likelihood of developing alcohol use disorders. Weekly volume of alcohol consumption also has been used as an early indicator of the risk of developing an alcohol use disorder. For men the danger level is 14 standard drinks per week and for women 7 drinks per week. Early detection of problem drinking should lead to further evaluation and specific intervention according to the needs of the individual. Environmental strategies that have been effective in preventing alcohol problems include such approaches as raising the minimum legal drinking age to 21, enforcing minimum purchase age laws, increasing alcohol taxes and reducing discount drink specials, and holding retailers liable for damage inflicted on others by intoxicated and underage patrons. These strategies are reviewed in greater detail in Chapter 5.

The dimensional approach of DSM-5, in contrast to previous categorical diagnoses, mirrors research findings that SUDs occur along a continuum. While some patients with milder, recent onset may be managed with outpatient therapy, those with more severe disorders may require inpatient care followed by a long period of aftercare. The tradition of 30 days of inpatient or residential care with uncertain follow-up is no longer considered the optimal approach. Clinical research also supports medication-assisted treatment using an array of Food and Drug Administration–approved medications, as discussed later in this report.

The past three decades have seen enormous advances in our understanding of the neurobiology of addiction. Until the 1940s, addiction was regarded as a moral failure that could happen only to people with “bad character.” As recently as 1988, the Supreme Court declared that the

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) did not have to pay benefits to alcoholics because their drinking was due to “willful misconduct.”1

As a result of the pioneering work of scientists at the Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky (Ludwig et al., 1978) and the discovery of the reward system by psychologists such as Olds (1958), our view of addiction has changed. We now know that addiction, defined as a compulsion to seek and take specific substances, is based on an aberration of normal brain function.

The reward system is a set of circuits and structures that work as a unit in lower animals as well as primates and humans. Previously, animals were thought to be incapable of addiction; now they can serve as models for research relevant to human patients. The reward system developed early in evolution and is present in modern humans in a form that remains essentially unchanged from that of our early ancestors (Maclean, 1955). It is a part of the brain that is essential for survival because it is activated by all types of rewards, including the basic ones such as food, water, and sex. Activation of this system (pleasure) produces reinforcement of specific behaviors that are needed for survival. The reward system also is involved in the formation of memories. The pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain, at a very fundamental level, are completely normal.

Unfortunately, certain plant products, such as opioids and cocaine, are, by coincidence, able to fit perfectly into receptors in the reward circuits where they can directly produce a sensation of reward or euphoria. Other substances, such as alcohol, are able to activate the reward system by stimulating the release of neurotransmitters called endorphins or by other more complex mechanisms. While normal activation of the reward system by constructive behaviors is important for survival, activation of the reward system by the use of drugs can lead to behaviors that are nonproductive or harmful.

Whereas a sense of pleasure normally is earned through constructive behaviors and natural drives, even a small amount of cocaine can directly activate this same pleasure system without the need for the usual work. Cocaine’s chemical structure blocks the reuptake mechanism of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Normally, nerve cells release dopamine and take it back up again after their signals are sent; cocaine blocks the reuptake process, causing continued high stimulation of the reward system. Dopamine accumulates in the space between nerve cells where signaling occurs (the synapses), and the cocaine effect takes over or “hijacks” the reward system (Ritz et al., 1987). Other addictive drugs, such as alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, and opioids, also directly activate the reward system; although

____________________

1 Traynor v. Turnage, 485 U.S. 535 (1988).

they do so through different mechanisms, the net result is a similar hijacking (Koob and Bloom, 1988).

When the reward system is hijacked in this way, the human or animal begins to choose the rapid drug activation over natural rewards such as food, water, and sex. Activation through drugs becomes repeatedly reinforced, establishing strong memories that are difficult to change. Theoretically, any human or animal can develop these strong, fixed memories that underlie addiction; however, hereditary factors influence the ease with which these memories develop. Genetic influences on addiction have been studied in both humans and animals. Large population studies have shown that many humans try drugs and do not particularly like the experience, while others experience pleasure and repeat the drug taking and, within a period of time that depends on genetic variables, become compulsive users (Anthony et al., 1994). Most addictions show substantial evidence of heritability (Goldman et al., 2005), suggesting that many alleles contribute to each type of addiction, but only in a few instances have the alleles been identified. Examples include alleles for ethanol metabolizing enzymes in alcoholism and alpha 5 nicotinic receptor subunit alleles in nicotine addiction. The net result is that only a few of those who initiate drug use go on to become addicts. The variables that influence the risk of progressing from a user to an addict are both genetic and environmental, but the influence of the genetic variables is similar to the strength of the genetic risk for other chronic diseases, such as diabetes or hypertension. Vulnerability to addiction thus depends largely on the luck of the genetic sorting at conception. Good people, smart people—anyone is at risk of developing an addiction given the presence of the right variable.

Using animal models, researchers can predict whether a drug will be abused by humans because of the similarity between the reward system in lower animals and humans (Brady and Griffiths, 1983). In cases where animals demonstrate liking a drug by working to obtain it, we can surmise that humans will be highly likely to like it as well. By developing addiction in animals, we can test different treatments to see which ones will reduce the animal’s drug taking with high predictive value. These advancements with animal models have served a great advantage in the development of new medications for addiction and substantially increased our understanding of addiction mechanisms (IOM, 1996; IOM and NRC, 2004; O’Brien, 2012).

Addiction tends to be a chronic disorder with remissions and relapses. Short-term treatments usually are followed by relapses. Expensive residential programs lasting 30 days or more are not successful unless followed by long-term (months or years) outpatient care and supported by 12-step programs (O’Brien and McLellan, 1996). Medications have been developed that reduce the craving for drugs and increase the probability of remaining abstinent. Other medications that are pharmacologically similar to drugs

of abuse, such as methadone or buprenorphine for opioid addiction, can be used for maintenance to help stabilize the patient and permit normal functioning. Chapter 5 reviews these and other effective treatments for SUDs.

Historically, the use of alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco has been common in the military. Heavy drinking is an accepted custom (Ames and Cunradi, 2004; Ames et al., 2009; Bryant, 1979; Schuckit, 1977) that has become part of the military work culture and has been used for recreation, as well as to reward hard work, to ease interpersonal tensions, and to promote unit cohesion and camaraderie (Ames and Cunradi, 2004; Ames et al., 2009; Ingraham and Manning, 1984). Alcoholic beverages have long been available to service members at reduced prices at military installations, including during “happy hours” (Bryant, 1974; Wertsch, 1991). Studies of the conflicts of the past decade in Iraq and Afghanistan have shown that military deployments and combat exposure are associated with increases in alcohol consumption, binge and heavy drinking, and alcohol-related problems (Bray et al., 2009; Jacobson et al., 2008; Lande et al., 2008; Santiago et al., 2010; Spera, 2011). These increases in alcohol use may be associated with the challenges of war, the alcohol being used in part as an aid in coping with stressful or traumatic events and as self-medication for mental health problems (Jacobson et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2010). The availability of and easy access to alcohol on military installations, due in part to reduced prices, may also play a role in its increased use.

Service members have engaged in illicit drug use (i.e., the use of illegal drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and marijuana and the nonmedical use of prescription drugs) since discovering that they reduced pain, lessened fatigue, or helped in coping with boredom or panic that accompany battle. In the modern U.S. military, drug use surfaced as a problem during the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Heroin and opium were widely used by service members in Vietnam, partly to help them tolerate the challenges of the war environment (Robins et al., 1975). It was estimated that almost 43 percent of those who served in Vietnam used these drugs at least once, and half of those who used were thought to be dependent on them at some time (Robins, 1974). In the active duty component of the military, marijuana has been the most widely used illicit drug since the early 1980s (Bray et al., 2009).

More recently, increasing misuse of prescription drugs among both civilians and military personnel has become a national concern (Bray et al., 2012; Manchikanti, 2007; Manchikanti and Singh, 2008). Unfortunately, misuse of these drugs has risen more rapidly in military than civilian populations, making this a substantial issue for military leaders (Bray

et al., 2009, 2010a, 2012). Misuse of prescription drugs in the military is associated with increases in the number of prescriptions for these medications that have been written to alleviate chronic pain among service members who have sustained injuries during a decade of continuous war. Indeed, Bray and colleagues (2012) found that the key driver of prescription drug misuse in the military is misuse of pain medications. Holders of prescriptions for pain medications were found to be nearly three times more likely to misuse prescription pain relievers than those who did not have a prescription.

Although opioid misuse has been increasing, little is known about the demographic, psychiatric, clinical, deployment, or medication regimen characteristics that may be related to such misuse. Nonphysician medics and corpsmen represent one source of prescription opioids for military personnel in the field. While opioids are an important tool in first aid on the battlefield, the increasing prevalence of opioid abuse in the military services suggests that both nonphysician and physician providers need more training in the use of opioids in the management and treatment of pain and the risks of opioid medication. During the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the military has increased its use of prescription medications for the treatment of pain and other health conditions (U.S. Army, 2012). This increase has raised awareness that greater availability of prescription medications may lead to greater potential for abuse. To begin addressing this concern, the Army has taken a positive step by curtailing the length of time for which a prescription is valid, but additional efforts will be needed to mount a comprehensive response to this complex issue.

Tobacco use also has long been common in the military, particularly after it was sanctioned in connection with World War I (Brandt, 2007), a stance that continued during World War II (Conway, 1998). Cigarettes became readily accessible to service members, partly because the War Department began issuing tobacco rations. Cigarettes were included in K-rations and C-rations and sometimes became more valuable for trading or selling than the food items in the rations (Conway, 1998). The harmful effects of tobacco have been well established (Office of the Surgeon General, 1967, 1979, 2004). Tobacco use has a negative effect on military performance and readiness and results in enormous costs (an estimated cost of $564 million to the Military Health System in 2006) (IOM, 2009).

DEVELOPMENT OF MILITARY SUBSTANCE ABUSE POLICY: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

The Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) series of policy directives aimed at decreasing and possibly preventing alcohol and other drug abuse originated in the early 1970s (DoD, 1970, 1972; The Controlled Substances Act of

19702), whereas policies directed toward smoking prevention were developed in the 1980s and 1990s (DoD, 1986a,b, 1987, 1994). DoD convened a task force in 1967 to investigate alcohol and other drug abuse in the military, and the resulting recommendations led to a policy directive in 1970 that guided military efforts targeting alcohol and other drug abuse during the 1970s (DoD, 1970). This policy emphasized the prevention of alcohol and other drug abuse through education and law enforcement procedures focused on detection and early intervention. Treatment was provided for problem users, with the goal of returning them to service. A urinalysis testing program was established to help deter illicit drug use, but the program was challenged in the courts3 and was discontinued from 1976 until the early 1980s.

In 1980, DoD updated its policy on alcohol and other drug abuse in a new directive (DoD, 1980) that focused on prevention and emphasized the goal of being free from the negative effects of such abuse. The policy emphasized the incompatibility of alcohol and other drug abuse with military performance standards and readiness. It continued to emphasize education and training, but gave less emphasis to treatment. This policy shift to prevention resulted from the view that many drug users were not addicted and thus were not in need of treatment (Allen and Mazzuchi, 1985). In 1981, however, drug use was one factor implicated in the crash of a jet on an aircraft carrier, resulting in further attention to the military’s drug problem. A new program to stop drug abuse was introduced, based largely on increased drug testing and the discharge of repeat offenders. Improvements in chemical testing procedures led to the decision that drug test results could be used as evidence if the procedures were strict enough to ensure that service members’ urine samples could not be misidentified. In 1981, the Navy introduced its “War on Drugs,” which initiated DoD’s emphasis on zero tolerance of illicit drug use. The other military branches soon followed the Navy’s lead and developed related programs, with drug testing playing a central role.

Beginning in 1986, policies on alcohol and other drug abuse were placed in the broader context of a health promotion policy directive. This directive, which focused on activities designed to support and influence individuals in managing their health through lifestyle decisions and self-care (DoD, 1986a), included prevention and cessation of smoking and prevention of alcohol and other drug abuse. In a related effort, DoD launched an antismoking campaign in 1986 that emphasized the negative health impacts of smoking. Subsequent efforts to curtail tobacco use resulted in further restrictions on smoking behavior, such as permitting smoking on base only

____________________

2 The Controlled Substances Act of 1970, Public Law 91-513, 91st Cong. (October 27, 1970).

3 U.S. v. Ruiz, Court Martial Reports 48:797 (23 U.S. Court of Military Appeals 181) (1974).

in designated smoking areas and offering smoking cessation programs to encourage smokers to quit (DoD, 1994; Kroutil et al., 1994). A 2009 Institute of Medicine committee that reviewed tobacco use in the armed services and the VA urged the military to become smoke-free, although many challenges to making this a reality remain (IOM, 2009).

Current DoD policy strongly discourages alcohol abuse (i.e., binge or heavy drinking), illicit drug use, and tobacco use by members of the military forces because of their negative effects both on health and on military readiness and the maintenance of high standards of performance and discipline (DoD, 1997). The U.S. military defines alcohol abuse as alcohol use that has adverse effects on the user’s health or behavior, family, or community or on DoD, or that leads to unacceptable behavior. Alcohol use is considered illegal for individuals under the age of 21 in the United States. Drug abuse is defined as the wrongful use, possession, distribution, or introduction onto a military installation of a controlled substance (e.g., marijuana, heroin, cocaine), prescription medication, over-the-counter medication, or intoxicating substance (other than alcohol) (DoD, 1997). Tobacco use is defined as use of cigarettes, cigars, pipes, snuff, or chewing tobacco and is discouraged because of its negative effects on performance and association with disease.

COMPOSITION AND SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ARMED FORCES

To better understand factors that influence substance use in the military, it is important to know the characteristics of the military population. The DoD services have an active duty component, comprising those who serve on active duty, and a reserve component, comprising those who serve in the Reserves and National Guard. The active duty component includes personnel from the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force; the reserve component includes personnel from the Army National Guard, Army Reserve, Navy Reserve, Marine Corps Reserve, Air Force National Guard, and Air Force Reserve. All Reserve and Guard members are assigned to one of three groups: the Ready Reserve, the Standby Reserve, or the Retired Reserve. The Ready Reserve is further divided into the Selected Reserve, the Individual Ready Reserve, and the Inactive National Guard. Because Selected Reserve members train throughout the year and participate annually in active duty training exercises, they are the Reserve group of greatest interest and can be thought of as Traditional Reservists.

Table 2-1 provides data on the size of the active duty and reserve components. As shown, the active duty component consists of slightly more than 1.4 million service members. The Army is the largest branch, representing nearly 40 percent of the active duty component, followed by

TABLE 2-1 Size of the Military Active Duty and Reserve Components in Fiscal Year 2010

| Enlisted | Officers | Total | ||||

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent of Component | |

| Active Duty Component | ||||||

| Army | 467,537 | 83.2 | 94,442 | 16.8 | 561,979 | 39.6 |

| Navy | 270,460 | 83.7 | 52,679 | 16.3 | 323,139 | 22.8 |

| Marines | 181,221 | 89.4 | 21,391 | 10.6 | 202,612 | 14.3 |

| Air Force | 263,439 | 79.9 | 66,201 | 20.1 | 329,640 | 23.3 |

| Total Active | 1,182,657 | 83.4 | 234,713 | 16.6 | 1,417,370 | 62.5 |

|

Reserve Component |

||||||

| Army National Guard | 319,846 | 88.3 | 42,169 | 11.7 | 362,015 | 42.6 |

| Army Reserve | 168,717 | 82.2 | 36,564 | 17.8 | 205,281 | 24.2 |

| Navy Reserve | 50,718 | 78.0 | 14,288 | 22.0 | 65,006 | 7.6 |

| Marine Corps Reserve | 35,423 | 90.3 | 3,799 | 9.7 | 39,222 | 4.6 |

| Air National Guard | 93,287 | 86.6 | 14,389 | 13.4 | 107,676 | 12.7 |

| Air Force Reserve | 55,559 | 79.2 | 14,560 | 20.8 | 70,119 | 8.3 |

| Total Reserve | 723,550 | 85.2 | 125,769 | 14.8 | 849,319 | 37.5 |

| Total Active and Reserve | 1,906,207 | 84.1 | 360,482 | 15.9 | 2,267,349 | 100.0 |

NOTE: Reserve component refers to the Selected Reserve, which comprises traditional drilling Reservists.

SOURCE: DoD, 2011a.

the Air Force and Navy, which are similar in size, and then the Marine Corps, which is the smallest. The reserve component (Selected Reserve) is much smaller than the active duty component, consisting of nearly 850,000 members. The Army National Guard is the largest branch of the reserve component (42.6 percent), followed by the Army Reserve, Air National Guard, Air Force Reserve, Navy Reserve, and Marine Corps Reserve. The Army National Guard and Army Reserve account for about two-thirds of the Selected Reserve. Together, the active duty and reserve components have just over 1.9 million members—62.5 percent in the active duty component and 37.5 percent in the reserve component.

Table 2-2 presents sociodemographic characteristics of active duty and reserve component personnel based on 2010 personnel counts reported by the Defense Manpower Data Center (DoD, 2011a). As shown, the groups are similar with regard to the distributions of gender and race/ethnicity. For example, the majority of both components are male (85.6 percent active duty, 82.1 percent reserve) and white (70.0 percent active duty, 75.9 percent reserve). Likewise, the two components have fairly similar levels of education and similar rank distribution. For example, the majority of personnel in both components are in the lower and mid-level enlisted pay grades, E1-E6.

In contrast to these similarities, there are two notable differences in the demographic composition of active duty and reserve component personnel. The first is that members of the active duty component are younger on average than those in the reserve component. For example, 65.3 percent of the active duty component is aged 30 or younger, compared with 51.9 percent of the reserve component. The second notable difference is that active duty component personnel are somewhat more likely to be married (56.4 percent) than reserve component personnel (48.2 percent), a fact that is somewhat surprising given the overall older ages of reserve component personnel.

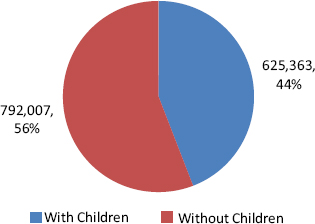

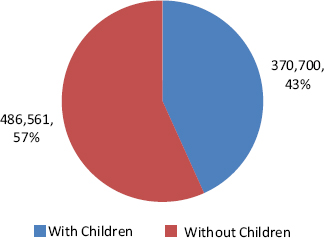

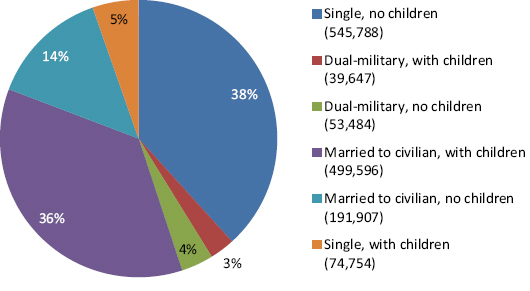

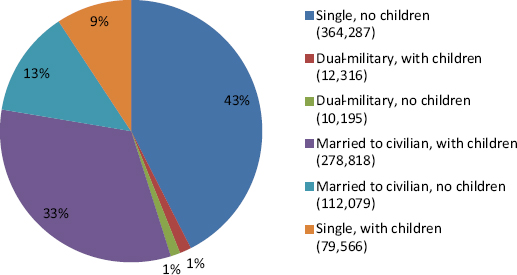

Figures 2-1 to 2-2 provide additional information on the family status of active duty and reserve component service members. As noted in Figures 2-1a and 2-1b, although the majority of active duty and reserve component personnel do not have children, more than 40 percent of members of both the active duty component (44 percent) and the reserve component (43 percent) do have children. Figures 2-2a and 2-2b provide a further breakdown of the various family configurations. As shown, the family distributions of the active duty and reserve components are highly similar. The largest groups are those who are single with no children (38 percent active duty, 43 percent reserve) and those who are married to civilians and have children (36 percent active duty, 33 percent reserve). The next-largest groups are those who are married to civilians and do not have children (14 percent active duty, 13 percent reserve) and those who are single and have children (5 percent active duty, 9 percent reserve).

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | Reserve Component (N = 849,319) (%) | Active Duty Component (N = 1,417,370) (%) |

|

Service Branch |

||

|

Army |

24.2 |

38.5 |

|

Army National Guard |

42.6 |

|

|

Navy |

7.6 |

22.1 |

|

Marine Corps |

4.6 |

13.9 |

|

Air Force |

8.3 |

22.6 |

|

Air National Guard |

12.7 |

|

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

82.1 |

85.6 |

|

Female |

17.9 |

14.4 |

|

Race |

||

|

White |

75.9 |

70.0 |

|

African American |

14.9 |

17.0 |

|

Asian |

2.8 |

3.7 |

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

0.9 |

1.7 |

|

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islandera |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

Multiraciala |

0.7 |

2.1 |

|

Ethnicity |

||

|

Hispanic |

9.5 |

10.8 |

|

Education |

||

|

No high school diploma |

2.9 |

0.5 |

|

Less than a bachelor’s degreeb |

76.7 |

79.5 |

|

Bachelor’s degree |

14.0 |

11.0 |

|

Advanced degree |

5.4 |

6.7 |

|

Age |

||

|

25 or younger |

33.3 |

44.2 |

|

26-30 |

18.6 |

21.1 |

|

31-35 |

12.2 |

13.8 |

|

36-40 |

12.1 |

11.1 |

|

41 or older |

23.8 |

8.8 |

|

Marital Status |

||

|

Not married |

51.8 |

43.6 |

|

Married |

48.2 |

56.4 |

|

Pay Grade |

||

|

E1-E3 |

19.5 |

24.6 |

|

E4-E6 |

53.9 |

49.3 |

|

E7-E9 |

11.8 |

9.5 |

|

W1-W5 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

|

O1-O3 |

6.3 |

9.0 |

|

O4-O10 |

7.1 |

6.2 |

NOTE: Reserve component refers to the Selected Reserve of DoD, which comprises traditional drilling Reservists and excludes Department of Homeland Security’s Coast Guard Reserve.

a The Army does not report “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” or “Multiracial.”

b Includes individuals with at least a high school diploma and possibly additional education less than a bachelor’s degree (e.g., associate’s degree).

SOURCE: DoD, 2011a.

FIGURE 2-1a Active duty component members with and without children.

NOTE: Children include minor dependents aged 20 or younger and dependents aged 22 and younger enrolled as full-time students.

SOURCE: DoD, 2011a, p. 52.

FIGURE 2-1b Reserve component members with and without children.

NOTE: Children include minor dependents aged 20 or younger and dependents aged 22 and younger enrolled as full-time students. Totals here include Department of Homeland Security’s Coast Guard Reserve.

SOURCE: DoD, 2011a, p. 116.

FIGURE 2-2a Active duty component family status.

NOTE: Single includes annulled, divorced, and widowed. Children include minor dependents aged 20 or younger and dependents aged 22 and younger enrolled as full-time students.

SOURCE: DoD, 2011a.

FIGURE 2-2b Reserve component family status.

NOTE: Single includes annulled, divorced, and widowed. Children include minor dependents aged 20 or younger and dependents aged 22 and younger enrolled as full-time students. Totals here include Department of Homeland Security’s Coast Guard Reserve.

SOURCE: DoD, 2011a. Figure 2-2b R02254

PREVALENCE OF SUBSTANCE USE IN THE MILITARY

As background for understanding SUDs in the military, it is useful to know the prevalence of substance use in the military. A much more substantial body of data is available to answer this question for the active duty than for the reserve component. Some data are also available on the prevalence of alcohol use disorders in particular for both components.

Substance Use in the Active Duty Component

The most comprehensive data on substance use in the active duty component come from the 10 DoD Surveys of Health Related Behaviors among Military Personnel (HRB Surveys), conducted from 1980 to 2008 (Bray et al., 2009, 2010a). These cross-sectional studies are particularly valuable in that they are population-based surveys with large sample sizes designed to represent the active duty component population. To encourage honest reporting on sensitive questions, respondents were asked to answer all questions anonymously.

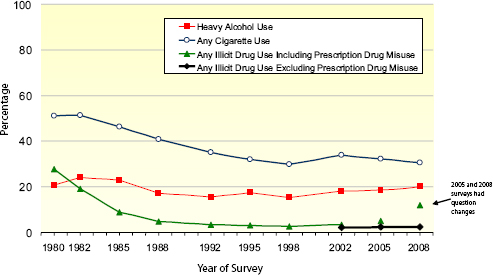

Figure 2-3 presents trends in past-month substance use (cigarettes, heavy alcohol, illicit drugs) for the active duty component from the HRB Surveys (Bray et al., 2009, 2010a). As shown, the prevalence of past-month cigarette smoking decreased significantly from 51 percent in 1980 to 30 percent in 1998, increased significantly from 1998 (30 percent) to 2002 (34 percent), and gradually declined in 2005 (32 percent) and in 2008 (31 percent) such that it was back to the rate reported in 1998.

Heavy alcohol use (defined as five or more drinks/occasion at least once per week) decreased significantly from 1980 (21 percent) to 1988 (17 percent), remained relatively stable with some fluctuations between 1988 and 1998 (15 percent), showed a significant increase from 1998 to 2002 (18 percent), and continued to increase gradually in 2005 (19 percent) and 2008 (20 percent). Rates from 1998 (15 percent) to 2008 (20 percent) show a significant 5 percentage point increase. It is also notable that the heavy drinking rate for 2008 (20 percent) was about the same as the rate when the survey series began in 1980 (21 percent).

Paralleling the increase in heavy drinking from 1998 to 2008, the HRB Surveys showed an increase in binge drinking (five or more drinks/occasion for men, four or more for women, at least once in the past month). Binge drinking increased from 35 percent in 1998 to 47 percent in 2008 (Bray et al., 2009), a 12 percentage point increase in a decade.

The prevalence of any reported illicit drug use (including prescription drug misuse) during the past 30 days declined sharply from 28 percent in 1980 to 3 percent in 2002. In 2005 the rate of illicit drug use was 5 percent, and in 2008 it was 12 percent. Improved question wording in 2005 and

FIGURE 2-3 Substance use trends for active duty military personnel, past 30 days, 1980-2008.

NOTES: Heavy alcohol use = 5 or more drinks on the same occasion at least once a week in the past 30 days. Any illicit drug use including prescription drug misuse = use of marijuana, cocaine (including crack), hallucinogens (PCP/LSD/ MDMA), heroin, methamphetamine, inhalants, or GHB/GBL or nonmedical use of prescription-type amphetamines/stimulants, tranquilizers/muscle relaxers, barbiturates/sedatives, or pain relievers. Any illicit drug use excluding prescription drug misuse = use of marijuana, cocaine (including crack), hallucinogens (PCP/LSD/ MDMA), heroin, inhalants, or GHB/GBL.

SOURCE: Bray et al., 2009.

2008 may account in part for the higher observed rates. Because of these wording changes, data from 2005 and 2008 are not directly comparable to data from prior surveys and are not included in the trend line. An additional line from 2002 to 2008 shows estimates of illicit drug use excluding prescription drug misuse. As shown, those rates were very low (2 percent in 2008) and did not change across these three iterations of the survey.

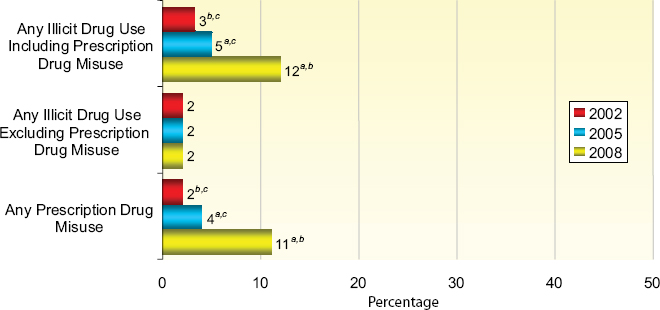

To better illustrate the relationship between overall illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse, Figure 2-4 presents three summary measures of illicit drug use in the past 30 days from 2002 to 2008: use of any illicit drug including prescription drug misuse, use of any illicit drug excluding prescription drug misuse, and any prescription drug misuse. As shown, past 30-day any illicit drug use excluding prescription drug misuse for active duty DoD service members remained stable from 2002 to 2008 at 2 percent. However, any illicit drug use including prescription drug misuse and any prescription drug misuse during the past 30 days increased significantly.

NOTE: Any illicit drug use including prescription drug misuse = use of marijuana, cocaine (including crack), hallucinogens (PCP, LSD, MDMA, and other hallucinogens), heroin, methamphetamine, inhalants, or GHB/GBL or nonmedical use of prescription-type amphetamines/stimulants, tranquilizers/muscle relaxers, barbiturates/sedatives, or pain relievers. Any illicit drug use excluding prescription Figure 2-4 R02254 vector editable landscape drug misuse = use of marijuana, cocaine (including crack), hallucinogens (PCP, LSD, MDMA, and other hallucinogens), heroin, inhalants, or GHB/GBL. Any prescription drug misuse = nonmedical use of prescription-type amphetamines/stimulants (including any use of methamphetamine), tranquilizers/muscle relaxers, barbiturates/sedatives, or pain relievers.

a Estimate is significantly different from the 2002 estimate at the .05 level.

b Estimate is significantly different from the 2005 estimate at the .05 level.

c Estimate is significantly different from the 2008 estimate at the .05 level.

SOURCE: Bray et al., 2009.

Any illicit drug use including prescription drug misuse among DoD personnel increased slightly from 3 percent in 2002 to 5 percent in 2005, but more than doubled from 2005 to 2008, from 5 percent to 12 percent. Any prescription drug misuse doubled from 2 percent in 2002 to 4 percent in 2005 and almost tripled from 2005 to 2008, from 4 percent to 11 percent. Other data from the 2008 HRB Survey not shown in Figure 2-4 indicate that the large majority of prescription drug misuse was attributable to the use of pain medications (10 percent in 2008) (Bray et al., 2009, 2012). Other, more recent data corroborate the military’s concern about the problem of prescription drug misuse (U.S. Army, 2012). Because of the punitive measures that result from illicit drug use in the military, there is likely to be some underreporting of drug use on surveys, so these numbers should be viewed as conservative estimates.

Analyses of the military prescription database by the Defense Health Board (2011) support the HRB Survey data in showing increases in drug prescriptions, particularly for narcotic pain killers, from 2001 to 2010. The increasing availability and use of prescription drugs opens up the possibility of higher rates of abuse, as noted by the Army (U.S. Army, 2012).

Other valuable information on illicit drug use comes from DoD statistics on positive drug screens from urinalysis testing (DoD, 2009). Among the active duty component, test results from fiscal year (FY) 2008 indicated a positive rate of 1.07 percent. This figure can be compared with a rate of 2.3 percent illicit drug use (excluding prescription drug misuse) during the past 30 days from the 2008 HRB Survey (Bray et al., 2009). Although these rates are not strictly comparable since they encompass different drugs and time frames, they both point to relatively low rates of illicit drug use.

Two new types of drugs—Spice and bath salts—have recently been gaining in popularity among civilians, partly because they are advertised as safe and legal, but the extent of their use among service members is not well documented. There is some evidence, however, that Spice abuse is beginning to occur among military personnel. The KLEAN Treatment Center reported that the military began conducting urine tests for Spice in March 2011, and that more than half of personnel tested were positive for its use (KLEAN Treatment Center, 2012). Spice is a synthetic cannabinoid that since 2008 has been detected in herbal smoking mixtures and when smoked produces effects similar to THC, the active ingredient in marijuana. Intoxication, withdrawal, psychosis, and death have been reported after consumption. Because it is easy to modify the chemical composition of the compounds (e.g., more than 140 different variations of Spice have been identified), it is also easy to avoid legal efforts to ban these substances (Fattore and Fratta, 2011; Vandrey et al., 2012; Wells and Ott, 2011).

Bath salts, known by such street names as “Ivory Wave,” “Purple Wave,” “Vanilla Sky,” and “Bliss,” are new drugs in the form of synthetic

powder that can be used to get high and are usually taken orally, inhaled, or injected. Bath salts, which can be obtained legally in mini-marts, smoke shops, or over the Internet, contain various amphetamine-like chemicals that can trigger intense cravings and pose a high risk for overdose (Winder et al., 2012). Referred to by some as a cocaine substitute, bath salts can result in chest pains, increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, agitation, hallucinations, extreme paranoia, and delusions and have been responsible for thousands of calls to poison centers (Kasick et al., 2012; Volkow, 2011). There are no published data at present on the use of bath salts in the military.

Characteristics of Active Duty Substance Users

Table 2-3 shows the characteristics of the heavy alcohol, cigarette, and illicit drug users from the 2008 HRB Survey (Bray et al., 2009, 2010b). It presents prevalence estimates and odds ratios adjusted for all of the other characteristics in the table. As shown, the overall prevalence of heavy drinking was 20 percent. The highest rates of heavy alcohol use occurred among those who were serving in the Marine Corps or Army, were men, were white or Hispanic, had less than a college degree, were single or married but unaccompanied by their spouse, and were in any pay grade except senior officers (O4-O10).

The prevalence of cigarette use was 30.7 percent. Smokers were more likely to be serving in the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps relative to the Air Force, and were more likely to be men, to be white non-Hispanic, to have less than a college degree, to be single, to be enlisted (especially pay grades E1-E6), and to be stationed outside the continental United States. The demographic profile shown in Table 2-3 is highly similar for heavy alcohol users and cigarette users.

The overall prevalence of illicit drug use (including prescription drug misuse) was 12 percent. Drug users were most likely to be serving in the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps relative to the Air Force; they were more likely to be women, to be Hispanic or “other” race/ethnicity, to be married but unaccompanied by their spouse, and to be enlisted.

Comparison of Active Duty Component and Civilian Substance Use Rates

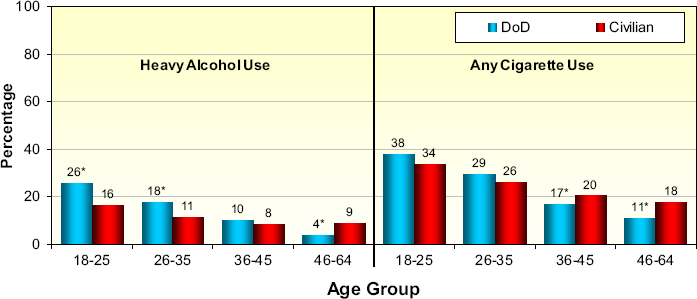

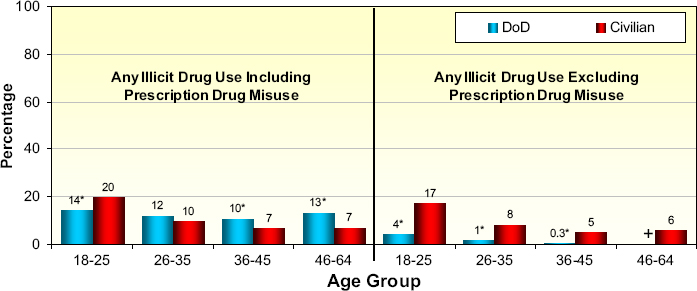

To provide some perspective on whether the levels of substance use in the military are higher or lower than might be expected, it is valuable to compare them against a benchmark such as rates of use in the civilian population. To this end, Bray and colleagues (2009) compared military data from the 2008 HRB Survey for active duty component personnel with

civilian data from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a nationwide survey of substance use. The two data sets were equated for age and geographic location of respondents, and civilian demographics were adjusted (reweighted) to reflect the demographic distribution of the military. Substance use rates then were recalculated for civilians assuming those demographics. Heavy alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and illicit drug use were compared for four age groups—18-25, 26-35, 36-45, and 46-64.

Figures 2-5a and 2-5b present the findings from these comparisons, which varied by type of substance and by age group. As shown in Figure 2-5a, active duty component military personnel aged 18-25 or 26-35 were significantly more likely than their civilian counterparts to have engaged in heavy drinking. There was no difference in rates for those aged 36-45, and the military rate was lower for those aged 46-64. Rates of past month cigarette use were lower for military personnel aged 36-45 or 46-64 than for comparable civilians; there was no significant difference in smoking rates between military personnel and civilians aged 18-25 or 26-35.

As shown in Figure 2-5b, service members aged 18-25 were less likely than civilians of similar age to use illicit drugs. This pattern was reversed for service members aged 36-45 or 46-64. Note that the higher prevalence of illicit drug use among these older age groups was due to the misuse of prescription drugs. If one looks just at illicit drug use excluding prescription drugs, the rates were lower for service members than for civilians in each age group.

As observed, substance use patterns in the military often differ from those among comparable-aged civilians. The higher rates of heavy drinking among younger military personnel compared with their civilian counterparts suggest that norms and expectations of military life may encourage heavy drinking or that military policy and prevention programs directed at reducing these rates have not been as effective as similar efforts among civilians. The comparable or lower rates of smoking in the military relative to civilians suggest that military efforts (e.g., restricted smoking areas, smoke-free buildings, antismoking campaigns) and/or secular trends in the civilian population played a role in reducing rates of smoking. The lower rates of drug use (excluding prescription drugs) among military personnel compared with civilians suggest either that military policies and practices deter drug use or that military personnel hold attitudes and values that discourage this behavior. However, the military is facing increasing challenges in managing drug abuse, as indicated by the apparent rise in prescription drug misuse. Given the military’s stringent policy prohibiting drug use and the strong deterrence of the urinalysis testing program, it appears likely that the difference in prevalence of drug use between military personnel and civilians is the result of military policies and practices.

| Heavy Alcohol Use | ||||

| Odds Ratioa | ||||

| Sociodemographic Character!srics | Adjusted Prevalence | Adjustedb | 95% CIc | |

| Service | ||||

| Army | 21.6 | (2.3) | 1.49* | (1.11, 1.99) |

| Navy | 17.9 | (0.7) | 1.16 | (0.99, 1.35) |

| Marine Corps | 25.2 | (1.1) | 1.84* | (1.53, 2.22) |

| Air Force | 15.9 | (0.9) | 1.00 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 21.8 | (1.2) | 2.97* | (2.49, 3.56) |

| Female | 8.9 | (0.8) | 1.00 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 21.6 | (1.1) | 1.00 | |

| African American, non-Hispanic | 14.3 | (1.2) | 0.59* | (0.52, 0.67) |

| Hispanic | 20.7 | (1.6) | 0.94 | (0.83, 1.08) |

| Other | 17.4 | (1.3) | 0.75* | (0.63, 0.88) |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 23.4 | (1.4) | 1.98* | (1.57,2.49) |

| Some college | 19.6 | (1.0) | 1.56* | (1.22, 1.98) |

| College graduate or higher | 13.8 | (1.3) | 1.00 | |

| Family Status | ||||

| Not married | 24.3 | (1.4) | 1.83* | (1.63, 2.06) |

| Married, spouse not present | 20.9 | (1.5) | 1.50* | (1.27, 1.77) |

| Married, spouse present | 15.3 | (0.9) | 1.00 | |

| Pay Grade | ||||

| E1-E3 | 18.8 | (1.5) | 2.27* | (1.47, 3.51) |

| E4-E6 | 22.6 | (1.1) | 2.92* | (1.96,4.33) |

| E7-E9 | 16.2 | (1.0) | 1.88* | (1.26, 2.80) |

| W1-W5 | 17.3 | (1.5) | 2.05* | (1.36, 3.10) |

| O1-O3 | 16.7 | (1.6) | 1.95* | (1.36, 2.81) |

| O4-O10 | 9.5 | (1.6) | 1.00 | |

| Region | ||||

| CONUSd | 19.4 | (1.6) | 0.89 | (0.73, 1.08) |

| OCONUSe | 21.2 | (0.7) | 1.00 | |

| Total | 20.0 | (1.1) | ||

NOTE: Prevalence estimates are percentages among military personnel in each sociodemographic group that were classified as heavy alcohol users, cigarette users, or illicit drug users in the past 30 days. The standard error of each estimate is presented in parentheses. These estimates were adjusted to obtain a model-based, standardized estimate. Heavy alcohol use is defined as consumption of 5 or more drinks on the same occasion at least once a week in the past 30 days. Any illicit drug use, including prescription drug misuse, is defined as the use of marijuana, cocaine (including crack), hallucinogens (PCP, LSD, MDMA, and other hallucinogens), heroin, methamphetamine, GHB/GBL, or inhalants or the nonmedical use of prescription-type amphetamines/stimulants, tranquilizers/muscle relaxers, barbiturates/sedatives, or pain relievers.

| Cigarette Use | Illicit Drug Use | ||||||

| Odds Ratioa | Odds Ratioa | ||||||

| Adjusted Prevalence | Adjustedb | 95% CTc | Adjusted Prevalence | Adjustedb | 95% CIc | ||

| 33.5 | (2.2) | 1.62* | (1.30, 2.02) | 15.8 | (0.7) | 2.21* | (1.92, 2.54) |

| 31.2 | (1.3) | 1.44* | (1.24, 1.68) | 10.0 | (0.6) | 1.31* | (1.11, 1.54) |

| 32.3 | (1.6) | 1.53* | (127, 1.83) | 11.5 | (0.8) | 1.53* | (1.28, 1.82) |

| 24.5 | (1.1) | 1.00 | 7.9 | (0.3) | 1.00 | ||

| 31.9 | (1.2) | 1.61* | (1.41, 1.84) | 11.7 | (0.4) | 0.85* | (0.76, 0.94) |

| 23.3 | (1.5) | 1.00 | 13.5 | (0.6) | 1.00 | ||

| 35.3 | (1.4) | 1.00 | 11.0 | (0.5) | 1.00 | ||

| 19.6 | (1.1) | 0.42* | (038, 0.46) | 14.5 | (0.8) | 1.38* | (1.16, 1.63) |

| 23.4 | (1.1) | 0.53* | (0.48, 0.59) | 12.9 | (0.9) | 1.20 | (0.98, 1.47) |

| 29.4 | (1.6) | 0.74* | (0.63, 0.88) | 13.0 | (0.8) | 1.21* | (1.05, 1.40) |

| 36.5 | (1.4) | 2.60* | (2.10, 3.22) | 12.9 | (0.6) | 1.14 | (0.88, 1.47) |

| 29.9 | (1.2) | 1.89* | (1.58,2.25) | 11.5 | (0.3) | 1.00 | (0.79, 1.26) |

| 19.0 | (1.4) | 1.00 | 11.5 | (1.2) | 1.00 | ||

| 31.7 | (1.3) | 1.14* | (1.06, 1.22) | 12.4 | (0.6) | 1.11 | (0.99, 1.24) |

| 32.2 | (1.6) | 1.16 | (0.98, 1.39) | 13.2 | (0.9) | 1.20* | (1.02, 1.41) |

| 29.3 | (1.3) | 1.00 | 11.3 | (0.3) | 1.00 | ||

| 33.6 | (2.8) | 5.02* | (2.94, 8.56) | 13.6 | (0.8) | 1.86* | (1.21, 2.87) |

| 34.7 | (0.8) | 5.28* | (3.30, 8.45) | 13.0 | (0.6) | 1.77* | (1.21,2.60) |

| 23.6 | (1.4) | 2.97* | (1.80,4.90) | 11.8 | (1.0) | 1.59* | (1.13,2.22) |

| 14.5 | (1.6) | 1.59 | (0.82, 3.07) | 5.6 | (2.2) | 0.69 | (0.25, 1.92) |

| 16.5 | (1.5) | 1.86* | (1.16, 3.00) | 5.7 | (0.7) | 0.70 | (0.44, 1.11) |

| 9.8 | (2.0) | 1.00 | 7.8 | (1.3) | 1.00 | ||

| 29.6 | (1.6) | 0.85* | (0.73, 0.98) | 12.4 | (0.5) | 1.13 | (0.98, 1.31) |

| 32.8 | (1.1) | 1.00 | 11.2 | (0.5) | 1.00 | ||

| 30.7 | (1.2) | 12.0 | (0.4) | ||||

a Odds ratios were adjusted for branch, gender, race/ethnicity, education, family status, pay grade, and region.

b An asterisk beside an estimate indicates that it is significantly different from the reference group.

c 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio.

d Refers to personnel who were stationed within the 48 contiguous states in the continental United States.

e Refers to personnel who were stationed outside the continental United States or aboard afloat ships.

SOURCE: Bray et al., 2010b.

NOTE: Heavy alcohol use = 5 or more drinks per occasion at least once a week in past 30 days for DoD, 5 or more drinks per occasion 5 or more times in past 30 days for civilians.

*Statistically significant from the civilian rate at the .05 level. Civilian data are from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (SAMHSA, 2008) and were standardized to the U.S.-based 2008 military data by gender, age, education, race/ethnicity, and marital status.

SOURCE: Bray et al., 2009.

*Statistically significant from the civilian rate at the .05 level. Civilian data are from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and

Health (SAMHSA, 2008) and were standardized to the U.S.-based 2008 military data by gender, age, education, race/ethnicity, and marital status.

+ Data not reported; low precision.

SOURCE: Bray et al., 2009.

Substance Use in the Reserve Component

Systematic data on substance use among the reserve component are limited as few surveys have been conducted on this population. The first large-scale population-based survey of the reserve component was conducted in 2006 (Hourani et al., 2007). A more recent follow-on survey of the reserve component was conducted in 2010-2011, but data from that survey were not available as of this writing. Analyses of the 2006 survey found that 6.6 percent of the Selected Reserves had engaged in illicit drug use (including prescription drug misuse) in the past 30 days and 12.0 percent in the last year. The past year estimate did not differ significantly from the past year rate of 10.9 percent for the active duty component from the 2005 HRB Survey. Additionally, 16.7 percent of reserve component personnel (Selected Reserves) reported past month heavy drinking, 40.4 percent reported binge drinking, and 23.7 percent reported cigarette smoking. Analyses that adjusted for demographic differences between the active duty and reserve components found that the rates for the reserve component were significantly lower than those for the active duty component on all three measures (Hourani et al., 2007).

DoD statistics on positive drug screens from urinalysis testing also provide information on members of the reserve component who are not serving on active duty (DoD, 2009). Among the reserve component, urinalysis test results from FY 2006 indicate a positive rate of 1.36 percent for Reservists and 2.26 percent for National Guardsmen. These rates are for a selected panel of drugs that does not include prescription medications and are not directly comparable to the survey data discussed above.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Findings:

Active Duty and Reserve Components

Excessive alcohol use has been shown to result in similar negative outcomes for military personnel and civilians. Mattiko and colleagues (2011) showed that negative outcomes had a curvilinear dose-response relationship with alcohol drinking levels. Higher levels of drinking were associated with higher rates of alcohol-related problems, which were substantially higher for heavy drinkers. Heavy alcohol users reported nearly three times the rate of serious consequences and more than twice the rate of productivity loss relative to the next-lowest level of moderate/heavy drinkers. These findings suggest that a qualitative shift in drinking problems may occur with increasing levels of consumption.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), developed by the World Health Organization as a simple method of screening for excessive drinking and assisting in brief assessment, is also useful for characterizing

the risk associated with drinking (Babor, 2001; Saunders et al., 1993). It consists of 10 questions scored 0-4 that are summed to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 40. The questions are primarily about consequences of drinking, signs and symptoms of problematic drinking, and quantity and frequency of drinking. Three levels of alcohol use risk can be identified: hazardous alcohol use, harmful alcohol use, and alcohol dependence. Hazardous use is a pattern of alcohol consumption that increases the risk of harmful consequences for the user or others; harmful use refers to alcohol consumption that results in consequences for physical and mental health; and alcohol dependence is a cluster of behavioral, cognitive, and physiological phenomena that may develop after repeated alcohol use (Babor, 2001). As defined by Babor and colleagues, AUDIT scores of 8-15 are indicative of hazardous drinking, scores of 16-19 suggest harmful drinking, and scores of 20 and above suggest possible alcohol dependence.

Table 2-4 presents AUDIT scores for the three risk levels for active duty and reserve component personnel using data from the 2008 HRB Survey for the former and the 2006 HRB Survey for the latter. As shown, 24.6 percent of active duty component service members had scores in the hazardous category of 8-15, 4.2 percent had scores in the harmful category of 16-19, and 4.5 percent had scores of 20 or higher suggestive of possible alcohol dependence. Across all three categories, about one-third (33.2 percent) of active duty component personnel had a score of 8 or higher, indicative of being at risk for some level of alcohol problems or consequences. The rates for reserve component personnel showed a similar pattern but were lower. About one-fifth of reserve component personnel (20.1 percent) had a score of 8 or higher, compared with one-third of active duty component personnel.

These data are informative in several important ways. First, in combination with other data presented above, they indicate that alcohol is a much larger substance use problem in the military than illicit drug use or

TABLE 2-4 Alcohol AUDIT Scores of Active Duty and Reserve Component Personnel

| Drinking Level | Active Duty Component (N = 24,640) (%) | Reserve Component (N = 15,212) (%) |

| AUDIT Score of 8–15 (Hazardous Drinking) |

24.6 | 14.3 |

| AUDIT Score of 16–19 (Harmful Drinking) |

4.2 | 2.7 |

| AUDIT Score of 20+ (Possible Dependence) |

4.5 | 3.1 |

| AUDIT Score of 8+ | 33.2 | 20.1 |

SOURCES: For active duty component, Bray et al. (2009); for reserve component, Hourani et al. (2007).

prescription drug misuse. Second, they indicate that substantial percentages of military personnel in both the active duty and reserve components are drinking alcohol at rates that place them at risk for alcohol problems, even though they do not meet the current criteria for alcohol dependence. Third, the data suggest that many problem drinkers would benefit from some type of alcohol intervention or treatment before reaching the most severe problem levels. This point is reinforced by an analysis reported by Mattiko and colleagues (2011). The authors compared drinking levels and AUDIT scores and found that more than 75 percent of heavy drinkers had an AUDIT score of 8 or higher, the level at which some type of intervention is recommended. The question then arises of whether personnel in need of treatment or other early intervention are receiving these needed services. The potential unmet need for treatment is examined in Chapter 7 of this report.

Alcohol- and Other Drug-Related Disorders:

Active Duty and Reserve Components

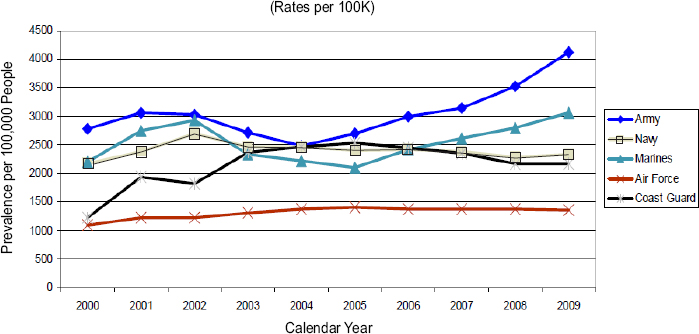

To gain insight into the trends in alcohol and other drug use disorders, the military conducted analyses of record data from the Military Health System Data Repository (MDR) and reported these analyses in the Comprehensive Plan. Counts of International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes indicative of alcohol and other drug use disorders were used to estimate the prevalence of substance abuse disorders among the active and reserve components (DoD, 2011b). Personnel included in the estimates had one or more diagnoses from a health care provider that had been entered into a clinical record. Ratings for alcohol were based on four codes indicative of alcoholic psychoses, dependence, intoxication, and abuse. Ratings for other drugs were based on 20 codes indicative of abuse and dependence for various drugs and drug combinations. Figure 2-6 shows the prevalence of alcohol-related disorders from FY 2000 to FY 2009 for the active duty component. As shown, there were initial increases in alcohol use disorder diagnoses, followed by decreases from 2000 to 2004 for the Army and Marine Corps, but substantial increases from 2005 to 2009. In contrast, the prevalence of these disorders for the Air Force and Navy remained relatively stable.

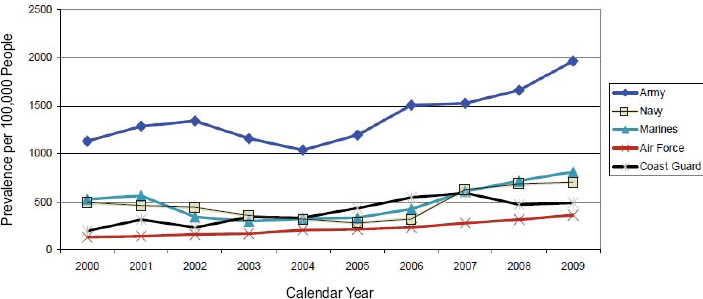

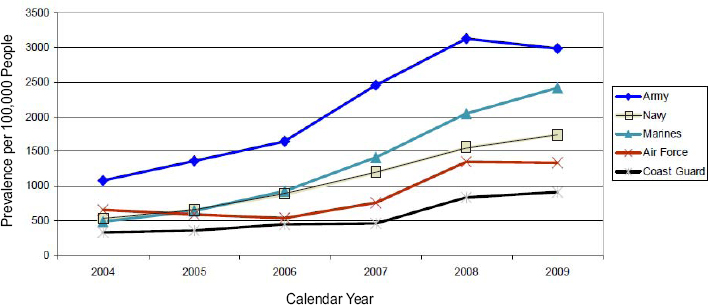

Figure 2-7 presents results for members of the active duty component who received a drug abuse diagnosis. As shown, there was an increase over the years for all branches, especially from 2004 to 2009. As with alcohol use disorders, the Army showed substantially higher rates of drug-related diagnoses than the other branches throughout the period. For the reserve component, data on alcohol and other drug use disorders were aggregated in the analyses from FY 2004 through FY 2009. Thus these data cannot be compared directly with the data in Figures 2-6 and 2-7. Figure 2-8 shows

this combined trend and, as with the active duty component, shows increasing rates over time, with the Army and Marine Corps having the highest combined rates.

Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders Among Military Dependents

The considerable information available on substance use among service members is in stark contrast to the limited empirical data on substance use among military spouses and children. One small study of military female spouses whose husbands were deployed (Padden et al., 2011) found that 3.9 percent reported illicit drug use, 12.4 percent reported binge drinking, and 27 percent reported tobacco use. Unfortunately, this was a small convenience sample of 105 spouses from a family readiness group, so the results are of limited generalizability.

Studies of military family members have tended to focus on the stress and mental health challenges they face. Indeed, the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan over the past decade have placed considerable strain on military families, who have had to cope with frequent and often lengthy separations due to the deployment of their service members. Not surprisingly, some of these deployment stressors, including fear for the safety of loved ones, single parent responsibilities, and marital strain, have had negative impacts on the spouses of military personnel (Schumm et al., 2000). Deployments have been associated with increased mental health diagnoses for spouses (Mansfield and Engel, 2011), with a higher likelihood of child maltreatment in military families (Gibbs et al., 2007), with poorer dietary behaviors, and with poorer stress management and rest (Padden et al., 2011). Eaton and colleagues (2008) found that rates of mental health problems among military spouses were similar to those among service members. However, spouses were more likely to seek mental health care and had less concern about the stigma of receiving that care relative to service members. Spouses also were an important influence on National Guard members who served in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars seeking care for their alcohol or mental health problems (Burnett-Zeigler et al., 2011).

Ahmadi and Green (2011) suggest that the stressors of military life, coupled with the fact that military personnel marry and have children earlier than their civilian counterparts, place service members at increased risk for substance abuse and for the development of adverse coping mechanisms. While this suggestion may have merit, the committee could identify no large-scale published studies examining substance use among military spouses and children. Mansfield and Engel (2011) suggest that this dearth of data with which to assess relationships between deployment stress and substance use points to the need for well-designed epidemiological studies to fill this information gap. The Millennium Cohort Study, an ongoing

prospective health analysis in the military, will soon be reporting survey data for military spouses (DoD, 2012). These data may serve as a first step toward providing some of this important information.

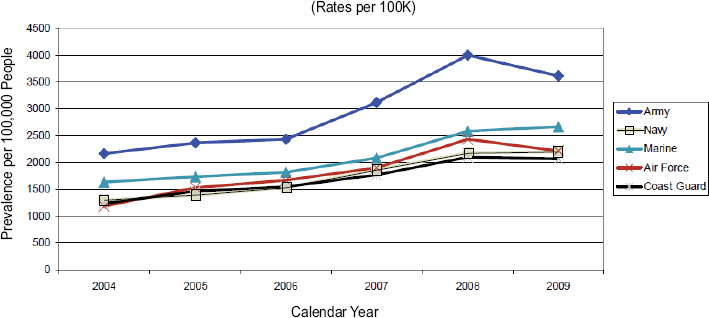

Data on trends in combined alcohol and drug use disorders for military dependents (spouses and children up to age 18) were included in the analyses of record data from the MDR database discussed above for active duty and reserve component personnel based on counts of ICD-9 codes (DoD, 2011b). Figure 2-9 displays the trends from FY 2004 to FY 2009. Similar to the patterns for the active duty and reserve components, rates of SUDs show gradual increases over the years for dependents in the Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force. Dependents in the Army show the highest rates and a gradual increase from 2004 to 2006, but a sharp increase from 2006 to 2008 and a decline in 2009. It is of interest that the pattern for dependents is similar to that for the active duty and reserve components, suggesting that there may be family patterns of alcohol and drug use leading to SUD diagnoses.

HEALTH CARE BURDEN OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

DoD recently published analyses of the absolute and relative morbidity burden among the armed services in 2011, grouping all medical encounters into 139 diseases and conditions (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2012a) based on ICD-9 codes. The morbidity burden attributable to a condition had four measures: (1) total number of medical encounters, (2) total number of service members affected (i.e., had one medical encounter for the condition), (3) total bed days during hospitalization, and (4) total number of lost duty days associated with seeking medical care for the condition. Table 2-5 shows the absolute numbers and ranks for the morbidity burden associated with substance abuse disorder and three selected mental disorders on three of these measures. As shown, the burden of substance abuse disorder for medical encounters ranked seventh among 139 conditions and for hospital bed days ranked first, even though it ranked only thirty-sixth for individuals affected. Substance abuse disorder and mood disorders accounted for nearly one-quarter (24 percent) of all hospital days. Together, the four mental disorders shown in the table (substance abuse, mood, anxiety, and adjustment) and two pregnancy- and delivery-related conditions accounted for one-half (50.3 percent) of all hospital bed days. Four conditions—upper respiratory infections, substance abuse disorder, mood disorders, and back problems—accounted for 24 percent of all lost duty days (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2012a).

These data suggest that DoD should place high priority on the development of new policies and programs to reduce the morbidity burden associated with substance abuse. Given that substance abuse imposes

| Medical Encountersb | Individuals Affectedc | Bed Daysd | ||||

| Major Category/Conditiona | No. | Rank | No. | Rank | No. | Rank |

| Anxiety disorder | 475,546 | 6 | 68,672 | 20 | 28,738 | 4 |

| Substance abuse disorder | 395,021 | 7 | 36,276 | 36 | 53,589 | 1 |

| Adjustment disorder | 385,122 | 8 | 89,563 | 15 | 26,456 | 5 |

| Mood disorder | 377,334 | 9 | 61,996 | 23 | 51,694 | 2 |

NOTES: The surveillance period was January 1 to December 31, 2011. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active duty component of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard at any time during the surveillance period.

aMajor categories and conditions modified from the Global Burden of Disease study. Rank is rank among 139 major categories and conditions.

bMedical encounters = total hospitalizations and ambulatory visits for the condition (with no more than one encounter per individual per day per condition).

cIndividuals with at least one hospitalization or ambulatory visit for the condition.

dTotal bed days for hospitalization and lost duty days due to the condition, measured as days confined to quarters and one-half day for a visit for the condition.

SOURCE: Adapted from Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2012a, Table 1.

disproportionately large morbidity and health care burdens relative to the number of service members affected, a further implication is that high priority should be given to focusing prevention resources and research on determining what effective universal, selective, and indicated prevention interventions could be introduced or expanded.

Substance Use and Comorbid Conditions

Substance use disorder prevention, diagnosis, and treatment must take into account the comorbid conditions that often result from the effects of war on service members. A recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report notes that “the trauma of combat, high-stress environments, or simply being deployed to a theater of war can have immediate and long-term disruptive physical, psychological, and other consequences in those who are deployed to foreign soil and to their family members” (IOM, 2010, p. 39).

Studies have suggested that multiple deployments and the high levels of stress associated with combat exposure and injury may increase the likelihood of behavioral and mental health issues among service members, including drug and alcohol abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and depression (Shen et al., 2012; U.S. Army, 2012). PTSD has been associated

with other comorbid mental disorders (Brady et al., 2000; Keane and Wolfe, 1990). For example, approximately 80 percent of individuals with PTSD have a comorbid psychiatric disorder at some time in their lives (Foa, 2009). Studies of psychiatric inpatients have found that more than 75 percent of PTSD patients have other psychiatric or medical diagnoses, including depression, suicidal ideation and attempts, alcohol and other drug abuse, anxiety, conduct disorder, chronic pain, and metabolic syndrome (Campbell et al., 2007; Floen and Elklit, 2007; Jakovljevic et al., 2006). A study of service members previously deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan (Tanielian et al., 2008) found that 14 percent screened positive for probable PTSD; 14 percent screened positive for probable major depression; 19 percent reported symptoms of probable traumatic brain injury (TBI) during deployment; and about one-third met criteria for PTSD, major depression, or TBI, with 5 percent meeting criteria for all three. Adams et al. (2012) found an association between TBI and past month reported binge drinking by military personnel after controlling for PTSD and combat exposure.

Comparing veterans of the Vietnam era with those of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, Fontana and Rosenheck (2008) found that, because of the emphasis on PTSD, the latter veterans were less often diagnosed and treated for substance abuse disorders. Regarding this finding, the Army notes that “current treatment of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans should take into consideration the potential for manifestations of substance abuse and violent behavior as well as the potential for recurrence or late onset of PTSD” (U.S. Army, 2012, p. 23).

Alcohol-Related Diagnoses

The Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (2011, 2012b) examined trends and demographic characteristics for acute, chronic, and “recurrent” alcohol-related diagnoses over a 10-year period from January 1, 2001, through December 31, 2010, for the active duty component of the military. Records of health care encounters, including hospitalizations and ambulatory care, in the Defense Medical Surveillance System were searched to identify those encounters that were associated with ICD-9 diagnostic codes encompassing both alcohol abuse and dependence indicators and were classified as acute or chronic cases. Acute cases were defined by four codes: (1) alcohol abuse/drunk, (2) toxic effect of alcohol, (3) excessive blood alcohol content, and (4) alcohol poisoning. Chronic cases were defined by eight codes: (1) acute intoxication in the presence of alcohol dependence, (2) alcohol-induced mental disorders, (3) other and unspecified alcohol dependence (chronic alcoholism), (4) alcoholic liver disease, (5) alcoholic cardiomyopathy, (6) alcoholic gastritis, (7) alcoholic polyneuropathy, and (8) personal history of alcoholism.

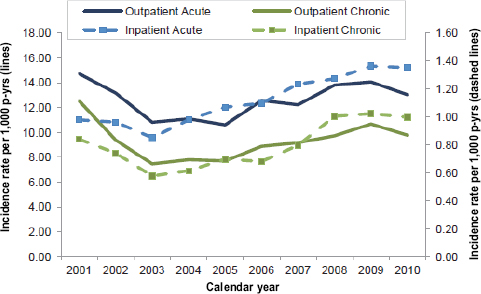

Figure 2-10 presents findings on the acute and chronic inpatient and outpatient cases from 2001 to 2010. As shown, there was a gradual increase in rates of acute and chronic incident (new) alcohol diagnoses during the latter part of the decade. Numbers of hospital bed days for acute alcohol diagnoses increased more than threefold. Incidence rates of acute and chronic alcohol-related diagnoses were highest in men aged 21-24 in the Army; for women, rates were highest among those under 21. In addition, there were sharp increases in alcohol-related medical encounters, especially from 2007 to 2010.

Initial analysis also indicated that approximately 21 percent of acute alcohol-related encounters were classified as “recurrent” diagnoses, meaning that during the 10-year period, personnel had a 12-month period that included three or more acute encounters. Following this initial report, some concern was expressed that individuals receiving treatment may have been misclassified as recurrent cases. A subsequent reanalysis using a revised algorithm found that 79 percent of cases originally classified as recurrent were likely treatment related, and further suggested that with this correction, approximately 4 percent of the initial cases would be considered recurrent (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2012b).

The results of this study indicate the increasing medical burden imposed on the Military Health System by excessive alcohol use and are especially

NOTE: p-yrs = person-years.

SOURCE: Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2011.

noteworthy with respect to personnel with chronic alcohol-related diagnoses. The number of bed days attributable to chronic alcohol abuse diagnoses roughly quadrupled over the 10-year period. This finding highlights the need for continued emphasis on the prevention, early identification, and treatment of alcohol-related disorders. (It should be noted that recent increases in incident alcohol-related diagnoses may reflect increasing scrutiny of alcohol use among military members and a concomitant focus on referrals for evaluation of alcohol misuse.)

CONCEPTUAL APPROACH TO PREVENTION, INTERVENTION, AND TREATMENT OF ALCOHOL USE PROBLEMS

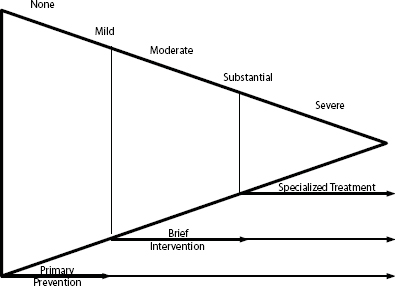

As suggested throughout this report, alcohol use is viewed as the key substance use problem in need of intervention and/or treatment among military personnel. Using health care as an example, Figure 2-11 presents a useful approach for conceptualizing alcohol use and likely associated problems in the military as they can be found in primary care, as well as intervention responses in that setting (IOM, 1990). The distribution of alcohol use (and associated problems) includes individuals drinking at nonharmful levels,

FIGURE 2-11 Alcohol use problems and interventions.

NOTE: The term “primary prevention” in this figure is used in the 1990 IOM report, but subsequent reports (including this one) use the term “universal prevention” instead.

SOURCE: IOM, 1990, p. 212.

those with unhealthy alcohol use who may be at risk for developing severe problems, and those with severe problems. The figure includes the spectrum of services the committee recommends to address alcohol use problems.

The bottom of this horizontal pyramid includes the largest portion of military personnel—those who do not use alcohol or who drink at levels causing no health, social, or public safety problems. (For drinkers in this category NIAAA specifies fewer than 5 drinks in a day and not more than 14 drinks in a week for men and fewer than 4 drinks in a day and not more than 7 drinks in a week for women.) Universal prevention targets this group. In line with evidence-based practice, the committee would suggest implementing programs consistent with the resiliency focus in the armed services—that is, including SUDs in the current teaching of resilience—as well as adding other evidence-based practices and policies that are implemented primarily in the community. The military is ideally structured for base commanders to institute environmental prevention strategies, including enforcement of existing underage drinking policies, removal of tax breaks for alcohol in exchanges (as is now being attempted with tobacco), and elimination of drink specials on premises.

The next-largest group of alcohol users in the pyramid includes those who may have a higher likelihood of developing unhealthy drinking habits as a result of particular risk factors, such as younger age or diagnosis of another mental health condition. These individuals would benefit from a targeted or selective prevention effort.

A third group of individuals includes those who are engaging in risky drinking but have not yet developed problems associated with their drinking. Individuals in this group can be identified through screening in primary care or other appropriate settings, such as the armed services’ substance abuse programs, or possibly by military buddies or noncommissioned officers in their units. The majority of these individuals are best served through motivational interviewing and brief advice. Educational interventions should be confidential—within the clinical practice. This approach is classified as indicated prevention and is consistent with DoD and VA guidelines. A subset of this group who have moderate problems often come into contact with Command through law enforcement or other disciplinary mechanisms as a result of being involved in an alcohol-related incident (e.g., driving under the influence); these individuals typically are sent to the substance abuse program of their particular service branch.

At the top of the pyramid is the smallest proportion of individuals—those with substantial or severe problems. This may also be the group most likely to have comorbid PTSD or other mental health problems. These individuals require specialized treatment. Approaches to addressing SUDs need to consider the full spectrum of problems faced by service members.

The military has a long history of use and abuse of alcohol and other drugs, and substance use often is exacerbated by deployment and combat exposure. To address these issues, DoD and the armed services developed and implemented a series of policy directives beginning in the early 1970s, largely as an outgrowth of concern about substance use during the Vietnam era. Current policy strongly discourages alcohol abuse (i.e., binge or heavy drinking), illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse, and tobacco use among members of the military forces because of the negative effects of these behaviors on health and on military readiness and the maintenance of high standards of performance and military discipline (DoD, 1997). Despite these official policies, however, substance use and abuse remain a concern for the armed services. Studies of substance use in the military show the following:

- Heavy alcohol use in the active duty component declined from 21 percent in 1980 to 17 percent in 1988, remained relatively stable with some fluctuations between 1988 and 1998 (15 percent), showed a significant increase in 2002 (18 percent), and continued to increase gradually in 2005 (19 percent) and 2008 (20 percent). It is also notable that the heavy drinking rate for 2008 (20 percent) was about the same as that when the HRB Survey series began in 1980 (21 percent).

- Binge drinking in the active duty component increased from 35 percent in 1998 to 47 percent in 2008.

- Illicit drug use in the past 30 days among the active duty component declined sharply from 28 percent in 1980 to about 3 percent in 2008.

- Prescription drug misuse among the active duty component doubled from 2 percent in 2002 to 4 percent in 2005 and almost tripled from 2005 to 2008, from 4 percent to 11 percent.

- Two new types of drugs—Spice and bath salts—have recently been gaining in popularity among civilians, partly because they are advertised as safe and legal, but the extent of their use among service members is not well documented.

- Compared with their civilian counterparts, active duty component military personnel were found to be more likely to engage in heavy drinking (a finding driven by personnel aged 18-35); less likely to use illicit drugs (excluding prescription drug misuse) among all age groups; and less likely to use illicit drugs (including prescription drugs) among younger personnel aged 18-25, but more likely to use these drugs among those aged 36 or older (a finding driven by prescription drug misuse).

- Rates of heavy drinking and illicit drug use were significantly lower for the reserve component than for the active duty component.

- Collectively, the data indicate that excessive alcohol use is a much greater substance use problem than illicit drug use or prescription drug misuse.

- Examination of alcohol risk based on AUDIT indicates that substantial percentages of military personnel (among both the active duty and reserve components) are drinking alcohol at rates that place them at risk for alcohol-related problems, even though they do not meet the current criteria for alcohol dependence; many problem drinkers would benefit from some type of alcohol intervention or treatment before reaching the most severe problem levels.

- Analyses of record data by the military indicate that alcohol and other drug use disorders have been increasing in recent years for the active duty component, the reserve component, and military dependents.