The Military Health System (MHS) provides care to specific military-connected beneficiaries in military health care facilities and certain civilian facilities where care is purchased. In reality, the MHS is not a single system and is fairly complex. Its beneficiaries are a diverse group, and include active duty service members (ADSMs), members of the National Guard and Reserves, retirees, and family members. The total beneficiary population is about 9.7 million.

Operational oversight of the Defense Health Program, both the direct and purchased care systems, resides in the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, through the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. The Army, Navy, and Air Force each have a designated surgeon general who has management responsibility for the branch-specific services. Since the Marine Corps does not have a Medical Command, any physicians serving with the Marines are Navy officers, and as such, come under the authority of the Navy surgeon general. Increasingly, facilities are being managed jointly by more than one branch. In the National Capital Region, for example, the services provided by the former Army Walter Reed Hospital and the National Naval Medical Center have been integrated into the new Walter Reed National Medical Center on the grounds of the former National Naval Medical Center. This consolidated site is staffed by providers from both the Army and Navy and provides care for service members from different branches of the military.

The general focus of the MHS is on ADSMs, fitness for duty, readiness, and care of the war fighter. In this context, substance use disorders (SUDs) generally are viewed as a condition that interferes with fitness for duty and service members’ ability to carry out their job duties, including

deployments, particularly since positive identification of an SUD may lead to separation from uniformed service. Thus, SUDs are sometimes viewed as personnel issues and at other times as medical conditions. As a result, both the Personnel and Medical Commands are involved in the identification and management of SUDs. Although the focus of military treatment facilities is operational readiness, the Department of Defense (DoD) for many years has expressed a commitment to providing substance abuse treatment to eligible beneficiaries.

This chapter provides an overview of the MHS. It describes the eligible beneficiaries, the direct care military treatment facilities, and the purchased care system. It also explains how service members and their dependents access SUD care and concludes with a summary.

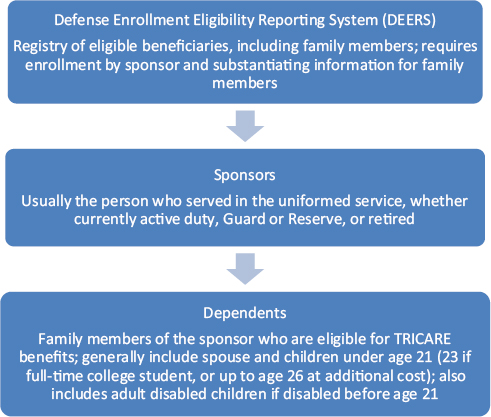

To be eligible for health care services in the MHS, including those for substance abuse, one must be either a “sponsor” (generally the person who has served or is serving in the uniformed services) or the sponsor’s family member (spouse; dependent child under age 21 or under age 23 if a full-time student, or up to age 26 at additional cost1; or adult disabled child if disabled before age 21). Eligibility is determined by enrollment in the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS), a computerized database of all beneficiaries eligible for health care and other uniformed services benefits (see Figure 3-1).

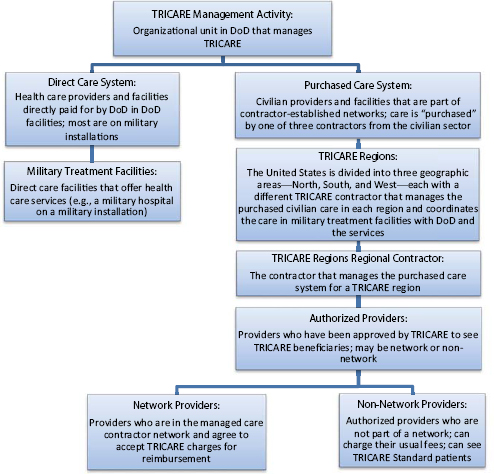

Military treatment facilities and the MHS in general are designed to ensure the operational readiness of the members of the uniformed services. Readiness is the ability of the uniformed services to be prepared for operational duties at all times. Readiness requires medical, dental, and mental health. DoD, in conjunction with the Department of Health and Human Services (for Public Health Service officers) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (for NOAA officers), has a statutory responsibility to provide health care to identified beneficiaries. This care is provided through the direct care system at military treatment facilities and through the purchased care system by reimbursement to authorized providers via the TRICARE insurance plans (see Figure 3-2).

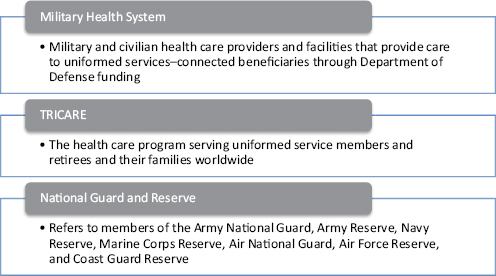

Members of each of the seven uniformed services (see Figure 3-3) have the same overall health care benefits under the TRICARE plans, which include coverage of behavioral health benefits such as substance abuse services. Further, members of the same beneficiary category (i.e., active duty, Guard/Reserve, retiree, family member) also have similar benefits across the different branches of the military, with the same TRICARE plans from which to choose.

____________________

1 TRICARE Young Adult, a provision of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

FIGURE 3-1 Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS).

Although active duty readiness is a major focus of the MHS, ADSMs and their dependents are becoming an increasingly smaller percentage of the total beneficiary population. In 1999, ADSMs and their dependents represented 57 percent of the beneficiary population, and retirees and their dependents 43 percent. By 2010, the active duty population had shrunk to 43 percent, while the retiree population had grown to 57 percent. By 2015, estimates are that only 35 percent of beneficiaries will be ADSMs and their dependents, while 65 percent will be retirees and their dependents. Because older beneficiaries tend to utilize health care services more than do younger persons, this changing demographic is contributing to the evergrowing costs of military health care (Jansen, 2009). Figure 3-4 provides definitions of terms related to TRICARE and the uniformed services health care system.

Active Duty Service Members and Their Dependents

ADSMs generally receive medical care at military treatment facilities or field health stations. ADSMs are automatically enrolled in TRICARE Prime

FIGURE 3-2 TRICARE organization of services.

FIGURE 3-3 The uniformed services.

and are required to utilize military treatment facilities when those facilities are available. If ADSMs want to utilize a civilian provider outside of the TRICARE system, they must obtain specific permission to do so, even if they have private health insurance (such as from a working spouse) or are willing to pay the costs out of pocket. It is viewed as a readiness issue, and also relates to the Command’s “need to know.”

FIGURE 3-4 Terminology related to the uniformed services health care system.

If readiness is to be maintained, the families of ADSMs also must receive the medical care they need. The stress of deployment would only be magnified if an ADSM were concerned about the health care available to his/her family members.

Active Duty Retirees and Their Dependents

Retirees and their dependents have earned their health care benefits through their years of active service. Until age 65, retirees and their family members have the option of participating in various TRICARE options, some with enrollment fees and copayments. When a retiree or family member reaches age 65 or is otherwise eligible for Medicare, TRICARE for Life becomes applicable. TRICARE for Life generally requires participation in Medicare Parts A and B and acts as a secondary payer. Beneficiaries usually bear no out-of-pocket costs for specific medical services received. TRICARE for Life also provides an enhanced benefit package over Medicare. Most TRICARE for Life benefits are provided by civilian TRICARE contractors; however, military treatment facilities provide care to these beneficiaries on a space-available basis as well.

National Guard and Reserve Members and Their Dependents

Members of the National Guard and Reserves and their dependents make up yet another beneficiary group. The specifics of coverage for this group are complex, depending on the particulars of the sponsor’s

military duty. With the increased support provided by the Guard and Reserves for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, greater numbers of Guard members and Reservists have been called to extended active duty. Accordingly, their health care benefit options have increased somewhat over time.

In general, if members of the National Guard or Reserves are on military duty for 30 days or less, such as for drilling, they qualify for care in the line of duty. Also, sponsors and family members are usually eligible for TRICARE Reserve Select, a premium-based program. When sponsors are activated or called to duty for more than 30 days, they and family members become eligible for essentially the same TRICARE benefits as other ADSMs. When Guard and Reserve members transition off active duty service, they are then eligible for the Continued Health Care Benefit Program (CHCBP), which the military offers to be in compliance with the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA). This program allows service members and their eligible dependents to maintain health insurance coverage for 18-36 months by paying the full premium. Additional details are presented in Tables 3-1 and 3-2. Note that since many Guard and Reserve members have private health insurance as part of their civilian jobs, they and their families have a lower TRICARE participation rate than other ADSMs.

Other Beneficiaries

In addition to ADSMs, Guard members and Reservists, retirees, and their family members, the direct care system provides care for a fixed fee to certain government officials on occasion, including the President and members of Congress. However, these populations represent a small fraction of the care given and are not considered further in this report.

DIRECT CARE: MILITARY TREATMENT FACILITIES

The direct care system includes the providers and facilities that are directly managed by the military services. They are organized by service (i.e., Army, Navy, Air Force) and are managed by each service’s surgeon general. Thus, there is variation among the branches in the policies and the specific ways in which those policies are implemented to meet overall statutory mandates and DoD directives. However, greater uniformity is expected to develop over time for substance abuse treatment as well as other medical care as the different branches of the military increasingly share resources and facilities to treat service members regardless of their branch. DoD recently was tasked to conduct an evaluation of the proposed shift toward a Unified Medical Command that would oversee the medical services of all

TABLE 3-1 Reserve Component Health Care Continuum

| Inactive Duty for Training/Selected Reserve | Active Duty Service | Predeployment | Deployment | Postdeploymenr | Transition Off Activity Duty |

| TRICARE Reserve Select (TRS) | TRICARE for Active Duty | Early Eligibility | TRICARE for Active Duty | Transitional Assistance Management Program (TAMP) | Continued Health Care Benefit Program (CHCBP) |

| TRICARE Standard | TRICARE Standard/Extra Prime/TRICAREPrime Remote (TPR) | TRICARE Standard/Extra Prime/TPR | TRICARE Standard/Extra Prime/TPR | TRICARE Standard/Extra Prime | TRICARE Standard/Extra Prime |

| Participating Selected Reserve | Inactive duty training (IDT)/active duty training (ADT) orders | Delayed effective date orders | Active duty orders | Contingency orders ≥31 days |

|

| Monthly Premiums (Not eligible if eligible for Federal Employees Health Benefits [FEHB] Program |

Coverage begins:

|

Coverage begins:

|

Coverage begins:

|

Coverage begins:

|

|

SOURCE: Powerpoint presentation by Brigadier General Margaret Wilmoth, Assistant for Mobilization and Reserve Affairs, U.S. Department of Defense, Office of Force Health Protection and Readiness, May 3, 2011, Washington, DC.

TABLE 3-2 Continuum of Care When on Active Duty

| Military Duty (30 days or less) | Preactivation* (90 days early eligibility) | Activation | Deactivation (upon leaving active duty) | Continued Coverage | |

| Medical—Guard/Reserve Member | Treatment for line of duty (LOD) conditions, TRICARE Reserve Select (TRS) | Full TRICARE coverage as active duty service mambers | Full TRICARE coverage as active duty service mambers | Transition Assistance Management Program (TAMP) coverage* | TRS or Continued Health Care Benefits Program (CHCBP) |

| Medical—Family Members | TRS | Full TRICARE coverage as active duty family members | Full TRICARE coverage as active duty family members | TAMP | TRS or CHCBP |

| Dental—Guard Reserve Member | Treatment for LOD conditions only | Full TRICARE coverage as active duty service members | Full TRICARE as active duty service members | TRICARE Dental Program (TDP) | TDP |

| Dental—Family | TDP (Reserve Component family member rates) | TDP (active duty family member rates) | TDP (active duty family member rates) | TDP (Reserve Component family member rates) | TDP (Reserve Component family member rates) |

*If active duty is in support of a contingency operation.

SOURCE: Powerpoint presentation by Brigadier General Margaret Wilmoth, Assistant for Mobilization and Reserve Affairs, U.S. Department of Defense, Office of Force Health Protection and Readiness, May 3, 2011, Washington, DC.

BOX 3-1

TRICARE Patient Priority System

|

Priority 1 |

Active duty service members |

|

Priority 2 |

Active duty family members enrolled in TRICARE Prime |

|

Priority 3 |

Retirees, their family members, and survivors enrolled in TRICARE Prime |

|

Priority 4 |

Active duty family members not enrolled in TRICARE Prime |

|

Priority 5 |

All other eligible persons |

branches.2 It remains to be seen whether the military will move forward with such a large reorganization of its health services.

DoD is required to provide care to ADSMs at military treatment facilities and also to their dependents on a space-available basis.3,4 While many categories of beneficiaries have some level of access to military treatment facilities, TRICARE Prime beneficiaries identify a facility where they will receive their primary care, and a specific primary care manager is then assigned. This provider manages their overall care and most referrals, including those for substance abuse treatment. Because of capacity limitations, military treatment facilities are unable to provide care to all eligible beneficiaries. TRICARE Prime beneficiaries generally receive care at their identified facility. Because of space limitations, however, a patient priority system has been developed for all beneficiaries (see Box 3-1). When military treatment facilities lack the capacity or capabilities needed by their primary beneficiaries, these beneficiaries generally can be seen by contracted civilian providers.

The direct care system includes 59 inpatient hospitals and medical centers and 363 ambulatory care clinics, staffed by roughly 85,000 ADSMs and 53,000 civilians. Substance abuse services are provided in only a fraction of these facilities (TMA, 2011a). Table 3-3 details how the 108 (as of July 2012) military treatment facilities that provide specialty care for substance abuse are distributed by TRICARE region and by state or foreign country.

____________________

2 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012, Public Law 112-81, 112th Cong. (December 31, 2011).

3 Scope and Duration of Federal Loan Insurance Program, 20 U.S.C. § 1074 (2012).

4 Medical and Dental Care for Dependents: General Rule, 10 U.S.C. § 1076 (2012).

| TRICARE Region | State/Country | Total |

| U.S.-Based | 91 | |

| North Region | Connecticut (1), Delaware (1), District of Columbia (1), Illinois (2), Kentucky (1), Maryland (6), New York (2), North Carolina (3), Ohio (1), Pennsylvania (1), Rhode Island (1), Virginia (3) | 23 |

| South Region | Alabama (3), Florida (8), Georgia (5), Kentucky (2) Louisiana (2), Mississippi (2), Oklahoma (3), South Carolina (2), Tennessee (1), Texas (5) | 33 |

| West Region | Alaska (2), Arizona (3), California (5), Colorado (3), Hawaii (4), Idaho (1), Kansas (3), Missouri (2), Montana (1), Nebraska (1), Nevada (2), New Mexico (2), North Dakota (1), Utah (1), Washington (4) | 35 |

| Overseas | 17 | |

| Overseas Pacific | Japan (5), South Korea (2) | 7 |

| Eurasia-Africa | Germany (5), Italy (2), Portugal (1), Turkey (1), United Kingdom (1) | 10 |

| Latin America | 0 | |

| TOTAL | 108 | |

SOURCE: http://www.tricare.mil/mtf.

As noted, to augment care provided by military treatment facilities, health care services are purchased from civilian providers. Overall, there are nearly 400,000 network individual providers for primary care, behavioral health, and specialty care. There are also more than 3,100 TRICARE network acute hospitals nationwide (TMA, 2011a). Most of the care is purchased through one of three large TRICARE contractors, one per TRICARE region. Each of these contractors maintains a network of civilian providers that provide a full range of services, including substance abuse services (GAO, 2011). The specific providers vary over time. Table 3-4 shows the states that make up the various TRICARE regions and the contractor responsible for each region.

Care through both the direct and purchased care systems is provided through a cluster of 12 TRICARE plans. The details of the specific plans affect the substance abuse treatment providers accessible to beneficiaries, as well as the co-payments. The 12 plans are based on four general models: (1) Prime, (2) Extra, (3) Standard, and (4) TRICARE for Life. (See Appendix E for a summary of these four models.)

TRICARE Prime options are essentially health maintenance organizations (HMOs). As noted earlier, beneficiaries have assigned primary care

TABLE 3-4 TRICARE Regions and Contractors

| TRICARE Region | States | Contractor |

| U.S.-Based | ||

| North Region | Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri (St. Louis), New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee (Ft. Campbell), Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin | Health Net |

| South Region | Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee (excluding Ft. Campbell), Texas (excluding El Paso) | Humana |

| West Region | Arizona, Arkansas, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa (except Rock Island Arsenal), Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri (except St. Louis), Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas (southwest corner), Utah, Washington, Wyoming | TriWEST* |

| Overseas | International SOS | |

| Overseas Pacific Eurasia-Africa Latin America |

||

*TriWEST lost the bid to renew its contract as the provider for the Western Region on March 16, 2012. It appealed this decision on May 3, 2012. The U.S. Government Accountability Office denied the appeal on July 2, 2012.

managers who make referrals for specialty care. The Prime options require pre-enrollment and use of network providers. ADSMs are automatically enrolled in TRICARE Prime.

TRICARE Extra options utilize preferred provider organizations, which domestically are typically networks managed by one of the three national TRICARE contractors. Providers participating in Extra options are authorized providers who agree to accept TRICARE reimbursement, which in most cases is based on Medicare reimbursement schedules. The Extra plans do not require pre-enrollment and have no annual enrollment costs. Although referrals for specialty care are not necessary, preauthorization is required for many services, including substance abuse treatment (TMA, 2012c).

TRICARE Standard is essentially a fee-for-service option utilizing authorized providers. Authorization involves a credential review and approval by TRICARE. Providers charge their usual rates, no pre-enrollment is required, and referrals are not necessary for specialty care. However, preauthorization is required for many services, including substance abuse treatment (TMA, 2012c).

TRICARE for Life is the Medicare “wrap-around.” As discussed earlier, TRICARE beneficiaries aged 65 and older who participate in Parts A and B of Medicare are eligible for this plan. They must pay the Medicare enrollment fees but no additional annual TRICARE enrollment fees. Medicare is the first payer; the TRICARE for Life plan generally pays all out-of-pocket Medicare costs and also provides some additional medical benefits (TMA, 2012a).

TRICARE Prime now has a Point of Service option, which allows TRICARE Prime beneficiaries to participate as well in features of TRICARE Standard and TRICARE Extra. Essentially, this option gives beneficiaries a greater choice of providers, although the providers must still be TRICARE authorized. Out-of-pocket expenses also increase. TRICARE Prime provides the most comprehensive benefit, although the choice of providers is more limited than is the case under TRICARE Extra and TRICARE Standard (TMA, 2011b).

TRICARE also has a pharmacy benefit with four options, each of which is available to all TRICARE beneficiaries. Prescriptions can be filled at a pharmacy at a military treatment facility at no cost. Prescriptions can also be filled through a mail order pharmacy program that is managed by a single contracted worldwide pharmacy home delivery vendor. This service is used most often for routine prescriptions taken for chronic conditions. The third option is a retail pharmacy, which includes almost 64,000 contracted network retail pharmacies. The retail pharmacies can dispense a maximum 30-day medication supply. Finally, non-network pharmacies can be used if the other options are not available. The mail order and retail pharmacy programs have some co-payments, which vary with beneficiaries’ duty status and whether the prescription is for generic or brand name products. Waivers are possible for nonformulary pharmaceuticals (TMA, 2012b).

CARE FOR SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS FOR MILITARY SERVICE MEMBERS AND DEPENDENTS

The preceding sections describe how ADSMs, members of the National Guard and Reserves, and their dependents access health care through the direct and purchased care systems. This section explains how each of these groups accesses SUD care in particular.

SUD Care Provided Through the Direct Care System

The SUD care available in the direct care system for service members and their dependents varies by service branch and location. The way each branch approaches prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, and management for SUDs is guided by overarching policies laid out by DoD, as

well as by branch-specific policies. These policies set forth clear guidelines for zero tolerance of drug and alcohol abuse, as well as the legal and administrative consequences of such abuse (DoD, 1997). The requirement to provide education focused on preventing drug and alcohol abuse, to conduct drug use testing, and to offer rehabilitation for substance use offenders also is laid out in DoD policies and instructions (DoD, 1985, 1994, 1997). Each branch is then responsible for developing its own branch-level policies to guide programs and activities that address SUDs. The branch policies set forth the specifics of how drug prevention, testing, and rehabilitation programs will operate. Some of the branch-level policies are more detailed than others and also address the responsibilities of personnel at different levels, as well as training and credentialing requirements for providers. Chapter 6 of this report provides a thorough review of all DoD and branch-level policies and programs addressing SUDs, while Chapter 8 details the requirements for credentialing and training for providers in these programs. The branches vary widely in how SUD care is delivered in the direct care system. In the Army, for instance, all SUD prevention activities and nearly all SUD treatment are provided under the authority of the Installation Management Command, which is responsible for all personnel issues. In contrast, the Navy houses all of its SUD treatment services under the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, its Medical Command, while prevention activities and services are delivered under the Personnel Command. This “ownership” by either the Medical or Personnel Command has implications for how care and services are delivered. Chapter 6 details the various types of SUD services and care that are provided within each branch of the military and the authority under which they operate.

SUD Care Provided Through the TRICARE Network

TRICARE is required to provide care for SUDs under the authority of 32 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 199.4.5 This care may include detoxification, rehabilitation, and outpatient group and family therapy. TRICARE provides a lifetime limit of three SUD treatment benefit periods (each benefit period is 365 days from the first visit), although this limit can be waived by the managed care support contractor that oversees the TRICARE plans for the region. Emergency and inpatient hospital services for detoxification and stabilization and for treatment of medical complications from an SUD do not start a benefit period for treatment. Emergency and inpatient hospital services are deemed medically necessary when the personnel and facilities of a hospital are required to manage the patient’s

____________________

5 Basic Program Benefits, 32 CFR § 199.4 (2004).

condition. All purchased treatment for SUDs requires prior authorization from the regional TRICARE contractor (TMA, 2008).

Chemical detoxification is covered for up to 7 days, although more days can be covered if medically or psychologically necessary. These 7 days count toward the 30- or 45-day limit for acute inpatient psychiatric care per fiscal year. If an inpatient general hospital setting is not needed, however, up to 7 days of chemical detoxification is covered in addition to any further rehabilitative care. Rehabilitation for SUDs may occur in an inpatient or partial hospitalization setting. Coverage encompasses 21 days (or one inpatient stay per benefit period) in a TRICARE-authorized facility. These 21 days also count toward the 30- or 45-day limit for acute inpatient psychiatric care (TMA, 2008).

Outpatient group therapy for SUDs must be provided by an approved Substance Use Disorder Rehabilitation Facility (SUDRF) (for more information on these facilities, refer to Chapter 7). The benefit includes 60 group therapy sessions in a benefit period. These sessions are in addition to the 15 sessions of outpatient family therapy covered by TRICARE. Family therapy is covered upon the completion of rehabilitative care (TMA, 2010). Note that individual outpatient therapy is not covered for SUDs unless it is provided through a SUDRF. As a TRICARE benefit, access to SUD services through contracted TRICARE providers requires preapproval through the contractor. Each of the contractors has a phone number that begins the preapproval process. SUD services can also be accessed through a provider-based toll-free number that is not limited to TRICARE beneficiaries; TRICARE specialists return all calls to this number and assist with referrals. Chapter 7 of this report describes the availability of and access to SUD care through the TRICARE benefit.

Other Avenues for SUD Care

In addition to the direct care and purchase care systems described above, members of the military and their families have several other avenues for SUD care. Like nearly all employers in the United States, the military has access to employee assistance programs; the specific contract provisions vary somewhat among the branches. An additional avenue is Military OneSource, which includes a website and nonclinical counseling that offer referral information on a wide range of topics, including substance abuse. Service members and their families may also receive care through Warrior Transition Units, the Soldier 360 Program, the Veterans Health Administration, and community programs such as Give an Hour. Some of these programs are reviewed in Chapter 6 and Appendix D of this report.

Through the direct care system and the TRICARE insurance benefit, the MHS provides comprehensive health care to military service members and their dependents. A multitude of insurance plans are available to eligible beneficiaries, along with a provider network that spans the globe. For the treatment of SUDs, service members and their dependents can access care both in military treatment facilities and through TRICARE network providers. The TRICARE SUD benefit notably does not reimburse for office-based outpatient treatment. The implication of this benefit limitation is discussed further in Chapter 7.

DoD (Department of Defense). 1985. Instruction 1010.6: Rehabilitation and referral services for alcohol and drug abusers. Washington, DC: DoD.

DoD. 1994. Directive 1010.1: Drug abuse testing program. Washington, DC: DoD.

DoD. 1997. Directive 1010.4: Drug and alcohol abuse by DoD personnel. Washington, DC: DoD.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2011. Defense health care: Access to civilian providers under TRICARE standard and extra. Washington, DC: GAO.

Jansen, D. 2009. Military medical care: Questions and answers. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

TMA (TRICARE Management Activity). 2008. TRICARE policy manual 6010.57-M. Falls Church, VA: TMA.

TMA. 2010. Treatment for substance use disorders. http://tricare.mil/substanceusedisorders (accessed May 24, 2012).

TMA. 2011a. Evaluation of the TRICARE program: FY 2011 report to Congress. http://www.tricare.mil/tma/downloads/TRICARE2011_02_28_11v8.pdf (accessed June 27, 2012).

TMA. 2011b. TRICARE prime and TRICARE remote handbook. Falls Church, VA: TMA.

TMA. 2012a. TRICARE for life. http://www.tricare.mil/mybenefit/home/overview/LearnAboutPlansAndCosts/TRICAREForLife (accessed June 14, 2012).

TMA. 2012b. TRICARE pharmacy program. http://www.tricare.mil/mybenefit/home/Prescriptions/PharmacyProgram (accessed June 14, 2012).

TMA. 2012c. TRICARE standard and extra. http://www.tricare.mil/standardextra (accessed June 14, 2012).