4

Health and Disability in the Working-

Age and Elderly Populations

As the remarkable increases in life expectancy of the last century combined with the U.S. baby boom to cause an unprecedented demographic transformation, a fundamental question became the functional status of the future population and the pattern that would emerge in the relationship between survival and functional capacity or disability.

The functional status of the working-age and elderly populations has very significant societal and economic consequences. For while it is certainly clear that the use of health care resources increases dramatically and progressively with advancing age after age 65, these increases are seen predominantly in those with disabilities. Changes in the age-specific prevalence and severity of functional impairment might therefore be expected to have major implications for health care costs, one of the principal macroeconomic issues related to the aging of the U.S. population.

In addition, it must be emphasized that disabilities, while most common late in life, can occur at any age and that it is very important to evaluate the current trends and likely future functional status in younger cohorts as they may have an important impact on these persons’ capacity to participate in the workforce and on their status as they enter late life. Thus, while the primary focus of studies of disability has been in those over 65, more recently there has been increased interest in the near elderly and younger age groups as well. Several recent studies, which will be reviewed in this chapter, shed light on these issues. Current and likely future disability rates in the so-called “young-old,” those aged 65–74, are of special interest, because the future workforce may well include many individuals in this age

group working part time or in flexible arrangements as a response to the later onset of social security benefits and increased workforce demands.

Recent research, reviewed in some detail in this chapter, indicates that rates of significant functional impairment for older (aged 65+) persons have been generally constant over the past decade after a two-decade period of progressive decline. Results for the “near elderly” are conflicting, probably for methodologic reasons, but there is clear evidence of the deleterious effects of increasing obesity on physical function as well as the well-documented beneficial effects of education and stopping smoking.

DISABILITY

Disability, generally defined as a limitation in the capacity to perform a given function, is traditionally considered in the framework of a process of disablement in which specific physiologic and pathophysiologic processes advance over time, resulting ultimately in a disability (Nagi, 1965; Verbrugge and Jette, 1994; Martin, Schoeni and Andreski, 2010). Various points along this spectrum may be identified. For instance the earliest stage is marked by the presence of preclinical markers, such as measures of inflammation or altered physiologic control such as high weight, blood pressure, or cholesterol. These risk factors may be followed by the presence of an identifiable disease, such as arthritis, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, or peripheral vascular disease, which can progress.

In arthritis, for instance, the earliest clinical signs may be very subtle, though biomarkers can be identified as demonstrating risk. As the disease progresses, one advances from joint stiffness and pain to actual difficulty performing tasks and ultimately to disability.

Reasoning that the same underlying secular changes in lifestyle (smoking cessation, more exercise, public health advances, etc.) and advances in the detection and treatment of disease and physiologic risk factors such as hypercholesterolemia that led to increases in life expectancy would also naturally delay the onset of functional impairment, many expected that increases in life expectancy would be yoked to stasis or reductions in late-life disability, leading to the “compression of morbidity” concept popularized by Fries (1980). The result would be an absolute increase in active life expectancy and a progressively shorter portion of the life span spent disabled. On the other hand, some have argued that technological advances in the treatment of disease might convert some once-fatal illnesses to chronic illnesses, increasing the duration of disability as life expectancy increases.

Common Measures of Functional Capacity and Disability

Traditional measures of disability in the population have been collected in national surveys of well-defined populations for many years. The major measures include the ability or inability to perform a function as well as the difficulty of performing it and the ability to perform it without assistance. The principal metrics employed in long-term, large-scale national studies include

- Activities of daily living (ADL). These tasks required to take care of oneself, such as bathing, toileting, eating, and dressing, are usually measured as difficulty performing them or receiving help in performing them. These are measures of fairly severe disability and predict need for personal care services and residence in a nursing facility for long-term care.

- Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). These tasks associated with the capacity to live independently, such as cooking, shopping, managing finances, and using communication devices, are measures of moderately severe disability and predict need for assistance such as homemaker and home health assistance.

- Physical limitations in activity. Examples are the ability to climb stairs, walk ¼ mile, stand or sit for prolonged periods, raise a 10 lb object over one’s head, climb steps, stoop, bend or kneel, grasp small objects, and move large objects. These limitations may reflect underlying disease and may predict capacity to participate in certain occupations.

- Cognitive function. While many aspects of behavior and cognitive function change with age, including speed of processing, changes in various vocabulary subsets, decision making, and the like, most surveys evaluating functional impairment have focused on general mental status, including orientation to time and place, working memory, attention, language, calculation, and familiarity with current affairs. For most cognitive measures that decline with age, studies show the declines to be very modest until at least age 70 and, in most cases, age 75. Thus the impact on the likelihood that this age group will participate in the workforce is minimal. Recently, Skirbekk, Loichinger, and Weber (2012) proposed the use of a cognitive-function-based measure—the cognition-adjusted dependency ratio (CAGR)—as a measure of aging in populations that avoids the pitfalls of simple age-based ratios such as an old-age dependency ratio and measures based purely on physical function.

The measurement of disability is evolving. There has been growing interest in the development of additional measures of disability that account

for technological change—for instance, individuals who previously were considered to have IADL disability because they could not shop or pay bills can now do these things online—and are more sensitive to the impact of the environment on functional capacity, including factors that restrict participation in activities. There has been interest as well in measuring a broader range of functional ability. Accordingly, a set of new self-reported measures has been developed and validated and will first be deployed in the emerging National Health and Aging Trends Study (Freedman et al., 2011). In addition, the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation has recently updated its module on disability, adding new measures related to communication, ability to function independently, and a variety of measures of physical functioning.

With respect to disease states, depression is by far the most common mental disorder that influences work and home life. Over 4 percent of Americans are estimated to suffer clinically significant depression during their life, with the disorder being twice as common in women as in men and peaking in prevalence in the 25–44 year age group (Elinson et al., 2004).

Databases

With some exceptions, analyses of functional status in community-based populations have relied on one or more of the following five nationally representative longitudinal survey-based datasets:

- The Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a panel survey conducted every 2 years beginning in 1992, focuses on people aged 51 and older living in the community. Functional measures include ADL, IADL, and mobility.

- The Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), a panel survey of Medicare beneficiaries, includes measures of ADL and IADL.

- The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), an annual cross-sectional household survey (one person responds with information on all household members) of the community-dwelling population, includes measures of ADL and IADL.

- The National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS), a nationally representative panel study of the population aged 65 and older living in the community or in institutions. The survey, which began in 1982 and was repeated at regular intervals until its termination in 2004, included measures of ADL and IADL.

- The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), an annual (since 1999) survey of about 5,000 adults and children, includes questions about the difficulty of performing ADL and IADL for those aged 60 and older.

Factors That Influence the Onset and Course of Disability

Disability is best seen as a function of the interaction of people’s physical capacity with demands presented by their life situation and a number of lifestyle, social, and environmental factors that influence their ability to perform a task. Technology also has an important impact on disability in many ways. This goes beyond the obvious benefits of assistive devices (hearing aids, glasses, hip replacements) and includes aspects of everyday life. As noted earlier, individuals who previously were considered disabled in terms of shopping, one of the traditional IADL measures, may now shop online and are thus no longer considered to have this disability. The built environment can also be important as the absence of stairs or the presence of elevators, ramps, or electric wheelchairs can dramatically improve mobility (Freedman et al., 2006; Crimmins and Beltrán-Sánchez, 2011). Lastly but important, social activity has been shown to have a “dose-dependent” favorable impact on the development of ADL or IADL disabilities (James et al., 2011).

Biomedical Factors

Biomedical factors independent of the disease process may increase or decrease the likelihood of disability at any given level of disease severity. For instance, individuals with lung disease or peripheral vascular disease will generally have their symptoms and disability increased if they smoke. And many initially obese patients with hip and knee arthritis find improvements with weight loss. Many obese patients seem to avoid heart disease despite the presence of biomedical risk factors like high blood pressure and high cholesterol as these factors are very commonly treated with effective pharmacologic agents (Martin, Schoeni, and Andreski, 2010).

The development of disability is a potentially reversible process. Clearly certain technologies such as hip or knee replacements or cataract removal promise dramatic reductions in disability, as do the less dramatic treatment of many diseases and many of the technologic, lifestyle, or environmental changes mentioned above. Such treatments can also increase the prevalence of disability in the population. For instance, changes in lifestyle (smoking, exercise) and improved treatment of risk factors (high blood pressure, high cholesterol) have decreased the incidence of stroke and, more recently, heart attack and some forms of cancer, reducing mortality and increasing survivorship and the prevalence of these disorders (Crimmins and Beltrán-Sánchez, 2011).

While it has been developing over several decades, the “obesity epidemic” (especially among certain racial and socioeconomic groups) has recently begun to attract widespread attention. Increases in weight beyond

the “normal” range, whether of moderate degree (overweight) or more marked (obese), have long been associated with increases in a number of important biomedical risk factors such as blood lipids, blood pressure, and blood sugar and have been shown to increase the risk for diabetes and a number of forms of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Over the last 30 years of the twentieth century, the prevalence of overweight tripled among children and adolescents while the prevalence of obesity in adults doubled to reach 33 percent (Ogden et al., 2007). Evidence is accumulating that this steady decades-long increase may have abated, as obesity and overweight rates seem to have flattened over the past decade (Ogden et al., 2006 and 2007; Martin, Schoeni, and Andreski, 2010).

Despite the widespread concern about obesity, some observers note that the adverse impact may be exaggerated in the media. Like many risk factors, the effect of increasing weight seems dose-related, with the greatest effects at extreme levels and only modest effects at low levels, despite the fact that such individuals may be labeled overweight or even obese (Wee et al., 2011). In addition, many of the metabolic risk factors associated with obesity, such as hypercholesterolemia, are now being effectively managed with medications, and the cardiovascular risk profile of today’s overweight and obese individuals may be improving. As Martin, Schoeni, and Andreski (2010) say, “Thus, for a variety of reasons, what it means to be obese may be changing, possibly for the better, over time.” A number of biomedical factors, including reductions in smoking, a plateau in the prevalence of obesity, and mitigation of its adverse effects through management, all point to positive changes in biomedically mediated disability in the future.

EDUCATION AND INCOME

Socioeconomic status (SES) has long been recognized as a major predictor of mortality, health status, and disability. The SES effect appears early in life and persists in a graded fashion so that advantage accrues as one “climbs the SES ladder” (Kawachi, Adler, and Dow, 2010). In most analyses education has been used as a proxy for socioeconomic status, which includes income and social status.

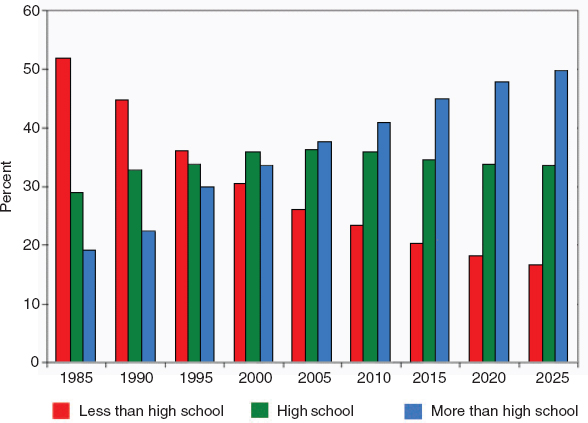

Analyses of the independent effects of education are complicated by the obvious selection effects (education is not randomly distributed) and by the clear confound with income, and studies that have tried to disentangle the two have generally shown that they have independent effects. Thorough analyses by Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2006 and 2010) conclude that the health-education gradient is found both for health behaviors and for health status and suggest that cognitive ability and decision-making patterns explain a large portion of the gradient. The effect of education on delaying the onset of disability is robust, dose-dependent, and pres-

ent across the lifespan (Taylor, 2010) (Figure 4-1). In addition to leading to higher income and professional status, thus providing greater access to health care, health insurance, and technological and personnel assistance, there are a number of other pathways by which education might influence the onset or course of disability, including enhancement of psychosocial resources, lifestyle differences (smoking, exercise), presence of fewer stressors such as marital or legal problems, and occupational factors—for example, more-educated individuals are less likely to be exposed to the risks of injury common in agricultural, commercial fishing, and construction work.

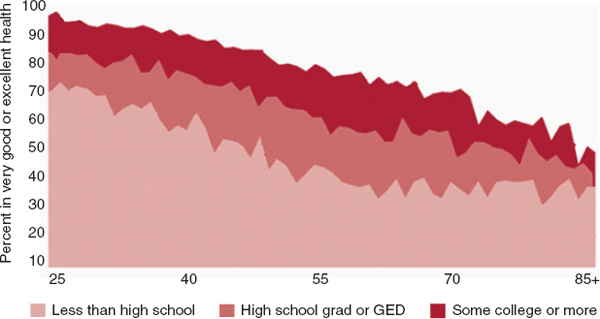

Since the beginning of the twentieth century there has been a very significant increase in educational attainment in the United States in successive cohorts of elderly (Figure 4-2). This secular change in education has been an important driver of changes in disability.

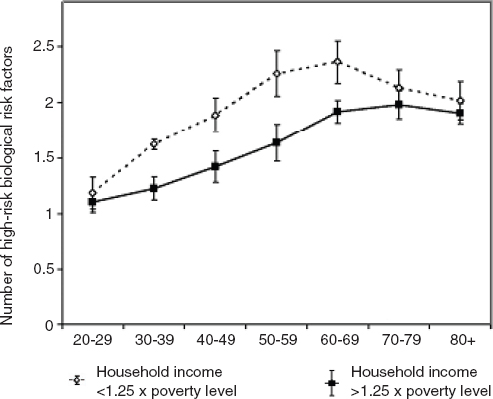

Poverty poses special risks as it is associated with significant increases in many biological risk factors for ill health and disability, especially during midlife. Poverty is related to not only the onset but also the course of disability, leading to the widely accepted view that the poor may age as much as a decade sooner than those who are well off (Crimmins, Kim, and Seeman, 2009; Taylor, 2010) (Figure 4-3). Regardless of the specific pathways operational in a given individual or group, it is abundantly clear that well-educated, high-income individuals are at greater advantage regarding survival and functional capacity while relatively uneducated, poor individuals are at greater relative risk.

FIGURE 4-1 Age, education, and functional decline, 2002–2004. SOURCE: MacArthur Foundation Research Network on an Aging Society (2009), based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

TRENDS IN DISABILITY

Working Age Population

As mentioned previously, the future workforce may include more individuals between the ages of 65 and 75 years. For this reason, and to better understand likely future disability trends in older persons, there has been a recent increase in interest in studying functional capacity in nonelderly adults, especially those over 40 years of age. In addition, an important advance has been the extension of measures of function beyond the traditional ADL/IADL to measures of less severe disability, such as mobility, which may not influence use of health care resources but may have an important impact on the capacity of persons to work in certain occupations.

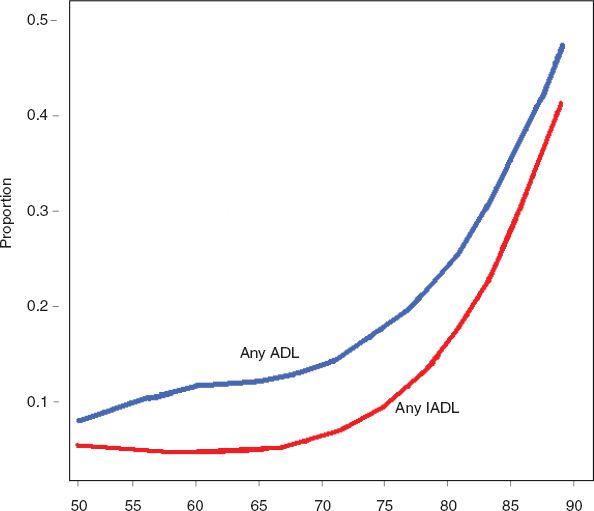

With respect to moderate or severe limitations of function in nonelderly individuals, several studies have indicated that rates of fair/poor self-rated health or of severe disability (ADL/IADL) for the near elderly have been gradually increasing over the past decade or two at a rate of about 1–2 percent per decade (Box 4-1). About 3–5 percent of near elderly report that they require help with either ADL or IADL (Figure 4-4), with as many as 14–16 percent reporting that they can perform these tasks alone but with difficulty (Freedman et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2009; Bhattacharya, Choudhry, and Lakdawalla, 2008).

Crimmins and Beltrán-Sánchez, using the National Health Interview Survey database and defining limitations as difficulty in any of four fairly robust functional measures (walking a quarter mile, climbing a flight of steps, standing or sitting for 2 hours, and bending or kneeling), found an increase in the prevalence of limitations in physical functioning that might be seen as reflecting less severe disability than ADL or IADL in middle age in all age groups between 1998 and 2006. For example, the limitation rate rose from 6.3 to 7.9 percent for men aged 50–59, and from 10.7 to 15.6 percent for men aged 60–69. Rates for women were higher than for men at all ages.

In contradiction to these findings, Martin, Schoeni, and Andreski (2010), using data from the NHIS for 1997–2008, found no changes over time in the proportion of people aged 40–64 who display difficulty in physical function. It should be noted that this study employed a much less strict measure of functional impairment (difficulty with any of nine measures, including walking a quarter mile, climbing 10 steps, standing 2 hours, sitting 2 hours, stooping, bending, or kneeling, reaching over one’s head, grasping small objects, and carrying 10 pounds or moving large objects) than did Crimmins and Beltrán-Sánchez. In unpacking the effects of various factors over time, Martin, Schoeni, and Andreski found that the stability in

BOX 4-1

The Economics of Disability

Key questions are why so many Americans are currently classified as disabled and why the incidence of disability has risen so quickly in the past three decades. In 1970, for instance, the proportion of beneficiaries of the government-run Disability Insurance (DI) program was below 3 percent; today it has risen to over 5 percent, and by 2030 is projected to be almost 7 percent (Social Security Administration, 2011). A partial explanation for the substantial run-up in the incidence of disability is the fact that Congress made it easier for those with mental illness and back pain to receive benefits.a Moreover, since people with these problems tend to live relatively long, the size of the disabled population has risen. Another explanation is that both the financial and in-kind benefits provided by the DI program have increased over time, making it more attractive for workers to apply than in the past. In addition, the rise in women’s labor market attachment has also raised the number of DI-insured workers, making it possible for more workers to claim benefits. Virtually none of the rise in DI receipt can be attributable to population aging or declining health (Autor and Duggan, 2006).

Future disability policy will surely have a powerful effect on labor force attachment patterns of Americans, because so many people are receiving benefits and because the financial flows associated with the DI program are so substantial. Policy makers coping with shortfalls in the nation’s safety net programs will need to carefully consider how generous the programs can be while at the same time encouraging employment among those who can work. Moreover, means of disability prevention also deserve more attention (Burkhauser and Daly, 2011).

_____________

aFor in-depth studies of the American disability system and proposals for change, see Autor and Duggan, 2006; Haveman and Wolfe, 2000; and Burkhauser and Daly, 2011.

reported disability resulted from a balance between the adverse effects of increasing obesity and the benefits of declining smoking rates.

The Elderly

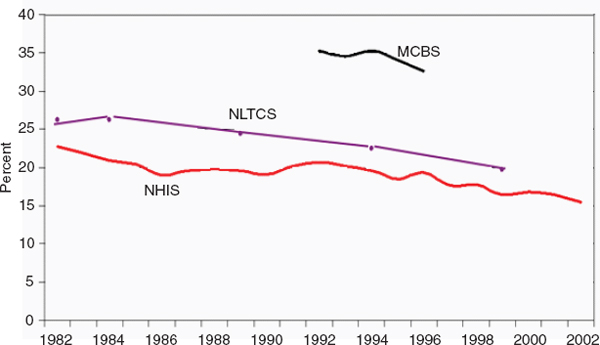

One of the strongest and most durable findings in disability research was the significant progressive reduction in functional impairment that occurred in older Americans from the 1980s into the early 2000s (Figure 4-5). Reductions in disability were prominent with respect to IADL but also were found, to a lesser extent, in ADL, indicating that both moderate and severe disability rates were falling (Schoeni, Freedman, and Martin, 2008; Freedman et al., 2004, Seeman et al., 2010). As discussed previously, medical advances and progressive increases in social factors, including education, likely mediated many of these improvements. As summarized by Freed-

FIGURE 4-4 Proportion of people aged 50–89 requiring help with one or more ADL or IADL, 2004. SOURCE: Data from Health and Retirement Study.

man (2011), these trends resulted in increases in active life expectancy and “compression of morbidity” during the 1980s and 1990s.

During the last decade, however, the picture has become quite murky, with disparate results and methodologic questions leading to uncertainty about whether these improvements were continuing. Recently several leading scholars in the area joined together in a robust analysis of all five of the large-scale databases noted earlier to evaluate trends in the functioning of older persons during the period 2000 to 2008. In general, the most consistent finding from this analysis was the lack of significant change in ADL or IADL for the 65- to 85-year-old population. For those over 85 the previous reductions in ADL seem to have continued, especially if one includes the nursing home population. This likely reflects continued increases in educational attainment in successive over-85-year-old cohorts during this time (Freedman et al., in press). The current prevailing view is that the period

FIGURE 4-5 Trend in disability rate for ages 65+ in three national surveys. SOURCE: Data as reported in the MCBS, the NLTCS, and the NHIS.

of declining ADL/IADL disability in older persons ended in the beginning of the last decade.

When it comes to less severe forms of disability, such as limitations in movement and the like, a different picture may be emerging. Using data from NHANES and NHIS, Martin, Schoeni, and Andreski (2010) found that two-thirds of the elderly had a limitation in at least one of the nine physical functions listed earlier. From 1997 to 2008 this prevalence was stable for males and increased gradually (1 percent per year) for females. The authors found, as did others who work in this area, that the effect of education was important and that the increase in educational attainment for the elderly during this time mitigated what would otherwise have been an increase in the prevalence of these limitations.

LOOKING FORWARD

The leveling off of disability decline in the older population, combined with apparent increases in disability among the working age population, complicates the forecasting of disability and related health care costs. In addition, other sources of uncertainty deserve mention. On the one hand, things could get worse than expected. Certain secular changes, such as the dramatic increase in overweight and obesity among the nonelderly and the

tendency for underprivileged populations to drop out of school, suggest that future generations may fare less well than their predecessors in this regard. Difficult-to-treat infectious diseases continue to emerge and could have a significant impact, especially later in life. What is more, the increasing political and economic pressures on entitlement programs that provide financial security and health care for older persons and the poor may have significant effects on their access to health care.

On the other hand, things could get much better. Continued advances in biomedicine, especially a cure for cancer or Alzheimer’s disease, could have remarkable effects, as would basic advances that slow the process of aging, which remains the major risk factor for disability. Of course, the committee is not interested in disability for its own sake but rather for its effect on the need for personal care services and its impact on the capacity of individuals to work. This latter consideration includes both those in the traditional “working age” category as well as those over 64 who may wish or need to work. In the next chapter the committee presents forecasts it commissioned of the size of the future workforce, including individuals up to age 74, based on several possible trajectories of disability change.