Appendix D

Collaboration Among Health Care Organizations: A Review of Outcomes and Best Practices for Effective Performance1,2

ABSTRACT

Despite the prevalence of collaborative ventures among health care organizations, including mergers, alliances, and joint ventures, the majority of these ventures fail to significantly improve the overall performance of the organizations involved. There is a great deal of variation in the outcomes of collaborative ventures, but results from several studies indicate that key practices, including effective leadership before, during, and after these ventures are implemented, may promote their effectiveness. This paper identifies these best practices for policy makers and managers concerned with improving the outcomes of collaboration among health care organizations. To this end, I (1) review evidence on the context and outcomes of collaboration among health care provider organizations and (2) examine results concerning the processes of change and implementation practices involved in efforts to collaborate (to what extent, and how, these factors affect the outcomes of collaboration). I conclude by presenting a checklist of best practices for improving the outcomes of collaboration and discuss leadership approaches for putting these practices into effect.

__________________

1 Prepared by Thomas D’Aunno, Ph.D., Columbia University, Department of Health Policy and Management, Mailman School of Public Health, with the assistance of Yi-Ting Chiang, M.P.H., and Mattia Gilmartin, Ph.D.

2 The authors are responsible for the content of this article, which does not necessarily represent the views of the Institute of Medicine.

INTRODUCTION

Hospitals and other health care organizations across the United States are engaging in collaborative ventures—including alliances, joint ventures, and mergers and acquisitions—at an increasing rate. Modern Healthcare’s (2012) annual mergers-and-acquisitions reports show, for example, a 3.5 and 3.4 percent increase in the number of mergers-and-acquisitions deals in 2010 and 2011, respectively, and a 73 percent increase in the number of hospitals involved in these deals from 2009 to 2010, the greatest increase in the past decade. Health care providers may be increasing their efforts to collaborate in response to the new risks and opportunities they face, stemming primarily from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the service delivery models it promotes, as well as related pay-for-performance reforms that aim to improve quality of care.

Unfortunately, the majority of collaborative ventures among health care organizations fail to significantly improve the overall performance of participants; there is a great deal of variation in outcomes (Bazzoli et al., 2004; Cartwright and Schoenberg, 2006; King et al., 2004). However, several study results indicate that key practices, including effective leadership before, during, and after these ventures are implemented, may promote their effectiveness (Hansen, 2009; Marks et al., 2001).

The purpose of this paper is to identify these best practices for policy makers and managers concerned with improving the outcomes of collaboration among health care organizations. I organize the paper as follows. First, I briefly define and distinguish major forms of collaboration, focusing on relationships among hospitals and physicians as the key organized providers of health care; this section also presents the conceptual framework that guided my work. Second, I review evidence on the context and outcomes of collaboration among health care provider organizations. Next, I examine results concerning the processes of change and implementation practices involved in efforts to collaborate—To what extent, and how, do these factors affect the outcomes of collaboration? I present a checklist of best practices for improving the outcomes of collaboration and discuss leadership approaches that can help put these practices into effect. I conclude with a discussion of observations about best practices for effective collaboration (Hansen, 2009).

COLLABORATION AMONG HEALTH CARE ORGANIZATIONS: DEFINITIONS AND DISTINCTIONS

This paper examines key forms of collaboration among health care providers who aim to coproduce services. I focus primarily on three major forms of collaboration among health care organizations: mergers and

acquisitions, alliances, and joint ventures. Further, following Bazzoli et al. (2004), I focus on these forms of collaboration among hospitals and physician groups—the two most important organized providers of health care services.

A merger is the consolidation of two or more firms, including the pooling of their assets, into a single legal entity. The terms merger and acquisition often are used interchangeably, but there is a technical difference between them: mergers are consolidations of equal partners, while in acquisitions one organization buys the assets of another.

In contrast to mergers are alliances, which are voluntary, formal arrangements among two or more organizations for the purposes of ongoing cooperation and mutual sharing of gains and risks (Zajac et al., 2010). Alliances are similar to mergers in that often they are formed for strategic purposes; that is, they aim to promote an organization’s mission and enhance organizational performance. Yet, members of alliances retain their legal independence; indeed, some alliance agreements are more informal than formal, and may involve little commitment of partners’ resources.

A joint venture is a formal agreement in which parties unite to develop, for a finite time, a new legal entity by contributing funds or resources of some kind (e.g., labor). The partners exercise control over the new organization and consequently share revenues, expenses, and assets. Because the cost of starting new projects is generally high, a joint venture allows both parties to share the burden of the project, as well as any resulting profits.

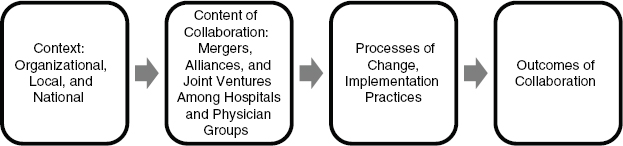

In sum, I focus on mergers, alliances, and joint ventures because they represent a continuum of approaches to collaboration among health care organizations, ranging from those that change the legal status of organizations (e.g., mergers and acquisitions) to those that involve the pooling of only limited resources among partners (e.g., joint ventures) to those that are less formal and involve commitments of fewer resources than either mergers or joint ventures (e.g., alliances) (Zajac et al., 2010). Figure D-1 shows the conceptual framework that guides this review and discussion.

FIGURE D-1 Conceptual framework of collaboration among health care organizations.

Here, based on prior research on organizational change (Pettigrew et al., 2001; Weick and Quinn, 1999), I aim to examine factors internal to health care organizations, as well as their local and national contexts, that can promote or hinder interest in collaboration and, importantly, affect the processes and outcomes of collaboration. In response to these internal and contextual factors, organizations may seek to collaborate with other health care providers. If so, they may select among major alternative forms of collaboration (i.e., mergers, alliances, and joint ventures), which, following Bazzoli et al. (2004), I term the content of collaboration. Next, processes of organizational change and implementation unfold as organizations aim to achieve their desired ends. Finally, these change processes result in a variety of outcomes.

Table D-1 elaborates the framework in Figure D-1 by indicating key variables in each stage of the model. As Table D-1 shows, I define the outcomes of interest broadly to include measures of quality, cost, and access to care; financial performance; productivity; and patient and stakeholder satisfaction.

To achieve the objectives for this paper, I reviewed relevant empirical studies in both the health care and non-health care sectors. I focused heavily on studies published in top-tier journals in the past decade, in part because useful reviews of prior work were available. Though I focused primarily on studies in the health care sector, researchers have studied collaborative strategy in non-health care industries for decades, and I also draw on this work.

COLLABORATION AMONG HOSPITALS

Collaboration among hospitals, through either mergers or alliances, has been relatively substantial for many years. The Premier hospital alliance, for example, spans the nation and now includes 2,300 hospitals; Premier makes $33 billion worth of purchases per year (Zajac et al., 2010). Current interest in hospital mergers was preceded by a large national wave of mergers that occurred between 1990 and 2003, resulting in an average reduction of competitors in metropolitan areas from 6 to 4 (Vogt and Town, 2006). By the mid-2000s, at least 88 percent of metropolitan residents lived in highly concentrated hospital markets, with even greater concentration in more rural areas.

Prior work indicates that hospitals have pursued mergers and alliances primarily to maintain or improve their financial performance (Bazzoli et al., 2004). Results from studies in the 1980s (e.g., Alexander and Morrisey, 1988) show that hospitals with weak financial performance were more likely to merge or join multihospital arrangements. In contrast, studies of hospital mergers and alliances in the 1990s suggest that these efforts were

TABLE D-1 Key Variables in Collaboration Among Health Care Organizations

| Organizational, Local, and National Contexts | Change Processes and Implementation Practices | Intermediate Outcomes | Long-Term Impact |

|

• Number and location of facilities • Size and number of people served • Local health care market—public and private sectors • Community support and needs |

• Early planning to manage both technical and people-focused tasks • Careful attention to roles of leadership, culture • Use of comprehensive, evidence-based checklist for implementation • Effective communications strategy—educating and orienting staff; mobilizing support • Adequate resources for transition management team |

• Staff satisfaction • Meeting quality-of-care benchmark measures • Patient satisfaction • Progress toward partners’ stated goals and objectives • Changes in service mix and operations: combining departments and services; transferring personnel • Developing shared information technology/electronic health records |

• Operating efficiencies, productivity • Overall financial performance • Patient functional health status; patient satisfaction • Increased market share in local area • Employee and other stakeholder satisfaction • Progress on partners’ stated goals and objectives for the collaboration |

more a response to external market pressure than to internal weaknesses; that is, strong hospitals anticipated that managed care would have negative effects on their financial performance, and sought mergers to protect themselves (Bazzoli et al., 2003, 2004).

The potential financial benefits from hospital mergers may stem from (1) price increases facilitated by increased market power; (2) cost reduction through economies of scope, scale, and monopsony power; and (3) favorable adjustments in service and product mix (Krishnan et al., 2004). To date, Bazzoli et al. (2004) and Vogt and Town (2006) have provided the most comprehensive analyses of research that addresses these issues; their

| Outcome | Form of Collaboration | ||

| Mergers | Multihospital Systems | Alliances | |

| Hospital prices | Mergers in metropolitan areas raised hospital prices by at least 5 percent and probably significantly more; studies of mergers among geographically-proximate hospitals show price increases of 40 percent or more | Some evidence for higher prices (Dranove et al., 1996; Young et al., 2000) | Some evidence for higher prices |

| Cost savings | Mixed results, but balance of evidence indicates that mergers result in cost savings for participating hospitals | Little or no cost savings (Dranove and Lindrooth, 2003) | Little or no cost savings |

| Revenue, profit | Mergers are consistently associated with higher revenue and profits | Higher revenues and profits | Some evidence for higher revenues per patient discharge (Clement et al., 1997) |

| Quality of care | Results are mixed, but evidence from the best studies indicates that mergers likely decrease quality of care (Hayford, 2011) | No quality improvement, with some evidence of decreased quality (Ho and Hamilton, 2000) | No quality improvement, with some evidence of decreased quality (Ho and Hamilton, 2000) |

reviews cover dozens of empirical studies. Table D-2 provides a summary of their analyses. In addition to examining the effects of hospital mergers and alliances, Bazzoli et al. (2004) reviewed studies of the effects of membership in multihospital systems; Table D-2 presents these results as a point of comparison.

Conclusions About Collaboration Among Hospitals

I draw several important conclusions from empirical studies of collaboration among hospitals. First, there is sound evidence that hospital mergers are linked to better financial performance for the participating hospitals: they have higher prices, revenues, and profits.

Second, hospital mergers lead to some cost savings, which, combined with charging higher prices, probably accounts for higher profits. Yet, the evidence on cost savings from mergers may be changing. Harrison (2011) recently reported results from a careful study of two hospital mergers that showed significant cost savings through economy of scale in the first year following a merger, but these cost savings decreased by the third year post-merger, and were no longer significant.

Third, in contrast to the results for mergers, there are fewer improvements in the financial performance of hospitals that join multihospital systems. Results from well-executed studies by Dranove and colleagues (1996; Dranove and Lindrooth, 2003) show increased prices and higher revenues for members of multihospital systems, but no cost savings.

Fourth, alliances do not seem to boost the financial performance of their member hospitals as much as mergers or multihospital systems.

Fifth, results show few quality-of-care benefits from collaboration among hospitals, and indeed there is some evidence for decreased quality of care following mergers. Some studies show no statistically significant postmerger changes in quality of care (Capps, 2005; Cuellar and Gertler, 2005), while others show a negative association. Hayford (2011), for example, analyzed 40 mergers among California hospitals from 1990 to 2006 and found that these mergers were associated with higher inpatient mortality rates among heart disease patients. Similarly, Ho and Hamilton (2000) found some evidence for decreased quality of care for heart disease patients in a study that compares hospitals’ premerger to postmerger performance using measures of inpatient mortality for heart attack and stroke patients and 90-day readmission rates for heart attack patients. Discrepancies in results may be due to the difficulty in isolating the effect of mergers per se on quality of care (Gaynor, 2006).

Finally, there is some evidence that the organizational structure of hospital systems and alliances can account for variation in their financial performance (Bazzoli et al., 2004). In a national study, Bazzoli and colleagues (1999, 2000) found some systems and alliances that exercised centralized control over a variety of decisions and others in which control was decentralized. Further, Bazzoli et al. (1999, 2000) showed that members of multihospital systems generally had better financial performance than hospitals in alliances. Hospitals that belonged to highly centralized alliances had better financial performance than those belonging to more decentralized

alliances. However, hospitals in moderately centralized systems performed better than those in highly centralized systems. Finally, hospitals in systems and alliances with little centralization experienced the poorest financial performance (Bazzoli et al., 2000).

In short, these results suggest that more centralized decision making in hospital systems and alliances leads to better financial performance for their members. This result may provide at least a partial explanation for the observation that “mergers among equals” seem difficult to implement (Kastor, 2001). That is, in mergers among hospitals that view themselves as equals, it may be more difficult to establish a centralized decision-making body because each party seeks to maintain its control over key decisions. Well-known examples include the failed “mergers of equals” between major teaching hospitals, in particular the Stanford University and the University of California, San Francisco, hospitals, and the Mount Sinai and the New York University hospitals (Kastor, 2001). More work is needed, however, to understand the effects of organizational characteristics, including the structure of decision making, on the financial performance of hospital systems and alliances (see Bazzoli et al., 2006; Luke, 2006; Trinh et al., 2010).

COLLABORATION AMONG PHYSICIAN GROUPS

Collaboration among physicians has occurred primarily through three types of organizations: group practices, independent practice associations (IPAs), and physician practice management companies (PPMCs) (Bazzoli et al., 2004). The number of IPAs and PPMCs has fluctuated, but the trend toward physicians working in groups has remained steady, resulting in an increased number of group practices (Boukus et al., 2009).

Studies of the relative benefits of collaboration among physician groups show results similar to those for hospitals. Identified benefits include opportunities for efficiencies in clinical care and management and greater power in negotiating contracts with insurers (Burns, 1997). Studies also show some unique benefits for physician groups: compared with the alternative of small, independent practices, mergers and alliances among physicians can increase their access to capital and management expertise (Robinson, 1998).

Most studies of collaboration among physicians have examined group practices that formed or grew through mergers or acquisitions. Summarizing results from several studies that examined the effects of collaboration among physicians, Bazzoli et al. (2004) draw three conclusions. First, there are limited cost savings; this result is similar to that reported for hospitals in multihospital systems and alliances (see Table D-2). Second, there can be important effects on physician use of resources, but these effects vary greatly and depend on the mechanisms used to monitor physician practice.

In a study of 94 physician organizations in California, for example, Kerr et al. (1995, 1996) reported the extensive use of quality assurance activities and a variety of utilization management techniques to control resource use. Yet, on balance, results from studies of physician resource use in group practices are mixed. For example, in contrast to Kerr and colleagues, Kralewski and colleagues (1996, 1998, 1999, 2000) found relatively few controls on physician resource use in the Minnesota group practices they studied. Finally, results are mixed for patient satisfaction in group medical practices.

COLLABORATION AMONG PHYSICIAN GROUPS AND HOSPITALS

Research suggests that physician groups and hospitals seek to collaborate for many reasons, only some of which overlap (Burns and Muller, 2008). Hospitals pursue closer relationships with physicians to

- capture outpatient markets;

- increase revenues and margins;

- improve care processes and outcomes;

- increase the loyalty of their physicians;

- bolster physicians’ practices and incomes; and

- address weaknesses in existing hospital medical staff.

Physicians likewise enter these relationships to increase practice incomes and improve the quality of service to patients, but, otherwise, their goals diverge from those of hospitals. Physicians want to increase their access to capital and technology and increase their control in care delivery.

Although physician-hospital collaboration takes many forms, the two most prominent are physician-hospital organizations (PHOs) and integrated salary models (ISMs) (Burns and Muller, 2008). PHOs are joint ventures designed to develop new services (e.g., ambulatory care clinics) or, more commonly, to attract managed care contracts. ISMs are arrangements in which a hospital acquires a physician’s practice, establishes an employment contract with the physician for a defined period, and negotiates a guaranteed base salary with a variable component based on office productivity, with some expectation that the physician will refer or admit patients to the hospital.

Within PHOs and ISMs, there are diverse relationships among physicians and hospitals that fall into three broad categories: noneconomic integration, economic integration, and clinical integration (Burns and Muller, 2008). Noneconomic integration includes hospital marketing of physicians’ practices, physician use of medical office buildings, physician liaison programs, physician leadership development, and hospital support for physi-

cian technology requests. Economic integration includes the PHO and ISM models above, as well as physician recruitment, part-time compensation, leases and participating bond transactions, service-line development, and equity joint ventures. Clinical integration encompasses practice profiling, performance feedback, medical/demand/disease management programs, continuous quality-improvement programs, and linkages via clinical information systems.

If success were gauged by interest among hospitals and physicians, these collaborations are doing quite well. Other evidence, however, is mixed. On one hand, there is a wealth of evidence that suggests that physicians are satisfied with these relationships to the extent that they receive valued services (e.g., management of their practices) and are shielded from financial risk (Bazzoli et al., 2004). On the other hand, evidence is inconclusive that hospitals value these relationships. In particular, a review of the empirical literature suggests that collaboration based on economic integration yields few consistent effects on cost, quality, or clinical integration. Alliances based on noneconomic integration are widespread, but have not been subjected to rigorous academic study. Finally, alliances based on clinical integration have had positive, but weaker-than-expected, impacts on quality of care (Burns and Muller, 2008).

There may be several reasons for the varied and relatively weak performance of hospital-physician ventures. One reason is the structural form used to implement them. These ventures are typically organized, financed, and controlled by the hospital, with little physician participation. Not surprisingly, physicians balk at partnerships in which they have little power. A second, related explanation is the lack of infrastructure in many alliances. Hospitals often develop alliances as external contracting vehicles to approach the managed care market but fail to develop the internal mechanisms that will help the alliance partners to manage risk (Kale and Singh, 2009). Such mechanisms include physician compensation and productivity systems, quality monitoring and measurement, and physician selection (Burns and Thorpe, 1997). Finally, alliances often focus on taking advantage of fee-for-service reimbursement systems and seek to increase numbers of patients and procedures rather than deliver more appropriate care.

These findings suggest that careful attention to infrastructure is critical for the success of physician-hospital alliances (Zajac et al., 1991). In the absence of the mechanisms discussed above, one would expect alliances to yield little impact on quality and cost of care. In fact, two recent studies have addressed this issue directly. Cuellar and Gertler (2005) and Madison (2004) report that PHO alliances do not lower the cost of care. Indeed, they may lead to higher prices due to the combined bargaining power of the parties.

TABLE D-3 Summary of Empirical Studies of Outcomes of Collaboration Among Health Care Organizations

| Outcomes | Hospital Collaboration | Physician Group Collaboration | Hospital-Physician Collaboration |

| Financial Performance | Higher prices; increased revenues and profit; little or no cost savings | Limited cost savings | Few consistent effects |

| Quality of Care | Few effects or decreased in quality | No evidence | Positive effects, but weaker than expected; inconsistent effects for clinical integration per se |

| Other Outcomes | The financial performance of two-hospital mergers is better than that of systems, which, in turn, have better financial performance than alliances | Mixed results for patient satisfaction; decreases in physician resource use depend on control mechanisms | Physician satisfaction increases with support services; inconclusive evidence for hospital satisfaction with hospital–physician collaboration |

SUMMARY

Table D-3 summarizes the major results from studies of the outcomes associated with the three major forms of collaboration I examined. As indicated, the strongest outcome seems to be that the financial performance of hospitals benefits from collaboration with other hospitals. Results for other outcomes are mixed and, importantly, there is substantial variation in the performance of collaborative ventures.

MAKING COLLABORATION WORK: IMPLEMENTATION AND ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

Researchers and practitioners have proposed several explanations to account for the substantial variation observed in the performance of collaborative ventures in health care and non-health care fields. The explanations themselves vary considerably and include, for example, a focus on improving

- due diligence and partner selection prior to implementing ventures;

- leadership to implement changes more effectively once a venture begins; and

- cultural integration of the partner organizations.

Following prior work, I consider the issues that these explanations raise in a three-part sequence: precollaboration activities, transition work, and postconsolidation follow-up (Zajac et al., 2010). Perhaps most importantly, in both research and practice, we need to give greater attention to the process of organizational change and implementation practices used in collaboration efforts. Indeed, prior research indicates that some practices for implementation and leading organizational change are more effective than others (Battilana et al., 2010; Cartwright and Schoenberg, 2006; Damschroeder et al., 2009; Kale and Singh, 2009). I explore this theme in more detail below, first by proposing and discussing a checklist of best practices to overcome typical barriers to effective collaboration. Next, I discuss the role of leadership and the organizational change processes needed to put these practices into effect. I conclude this section by applying concepts, principles, and practices from the checklist and leadership and change literatures to interpret evidence from studies in health care. In doing so, I show how best practices can overcome barriers to change.

Checklist for Managing the Implementation of Collaborative Ventures

Box D-1 shows a checklist of best practices or steps that prior research indicates could prevent or mitigate typical problems that organizations and managers encounter in collaboration projects. The list draws on empirical studies from health care and non-health care fields, and is organized in chronological sequence from precollaboration to follow-up work. It is important to note, however, that prior studies have examined only a few of these practices in combination and have not examined their importance relative to each other. Thus, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the extent to which any of the practices, or combinations thereof, might be more important than others for effective collaboration among health care organizations.

Precollaboration Issues

Selecting partners effectively is critical at this stage. An important distinction is that potential partners can relate to each other symbiotically as well as competitively, or sometimes both symbiotically and competitively (Hawley, 1950; Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978). Prior work indicates that collaborative ventures may be more likely to emerge when potential partners

I. Precollaboration Issues

a. Cost-benefit analysis

i. Choosing a collaboration model

ii. Potential for reconfiguring resources through collaboration

b. Partner selection

i. Strategic intent

1. Mutual and individual organizational interests

2. Mission/vision alignment

ii. Cultural compatibility

iii. Context

c. Strategic planning

i. Planning committee

ii. Setting priorities

II. Transition Issues

a. Governance

i. Monitoring and evaluation

ii. Problem analysis and solution

b. Decision making

c. Conflict management

d. Critical success and failure factors

i. Speed of collaboration

ii. Communication with employees

III. Follow-Up Issues

a. Cultural integration

b. Human resources

i. Redeploying; managing layoffs; reducing employee resistance

c. Operational integration

i. Resource allocation

d. Ongoing governance

have complementary relationships such that one organization uses some services or products from the other, as opposed to a relationship in which two organizations must vie for the same resources. A common example of such complementarity or symbiosis is a rural community hospital that refers cases for tertiary care to an urban teaching hospital. A recent review of 40 studies of alliances concluded that the complementarity of partners not only promotes alliance formation, but also contributes to alliance performance (Shah and Swaminathan, 2008).

Partner selection also should take into account potential antitrust issues. Mergers, alliances, and joint ventures have often served as vehicles to leverage managed care payers, for example, and thus have run afoul of antitrust actions taken by the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice (Casalino, 2006).

Considerations about the form of collaboration are also important at this stage. Each potential partner should plan carefully by constructing net present valuations of alternative relationships on a continuum ranging from maintaining the status quo (i.e., maintaining independence and arm’s-length transactions with other organizations) to forming alliances or joint ventures (i.e., a formal cooperative arrangement among organizations, preserving the independent identity of each partner) to the merger of two or more organizations (Macneil, 1983). Perceptions of what each partner seeks also should be communicated clearly at this time, enabling the precise identification of similarities and differences that can form the basis for mutually beneficial exchanges.

Thus, in this early stage, there is preliminary communication and negotiation concerning mutual and individual organizational interests. As a result, the partners learn not only about each other’s interests, but also about their compatibility, that is, the fit between their working styles and cultures. An organization’s behavior in this stage can set a precedent for future exchanges and provides information about the expected behavior of its partner. During this phase, initial norms are being forged and commitments tested in small but important ways to determine credibility (Macneil, 1983).

Though it is important for the expectations of partners to be realistic, it turns out that many young ventures have broadly-stated goals that do not necessarily coincide with their activities. This is because goal statements reflect compromises made by partners who are, as of yet, not willing to subordinate their interests to those of the venture as a whole.

Finally, in a useful summary, Kale and Singh (2009) conclude that variation in the performance of alliances stems from variation in the management and organizational capabilities of alliance partners; Marks et al. (2001) draw a similar conclusion about mergers. In short, management literature suggests that experience in collaborative efforts (e.g., the extent to which an organization has been involved in strategic alliances previously) plays a crucial role in determining their success (Anand and Khanna, 2000; Hoang and Rothaermel, 2005).

Transition Phase

In this stage, partners should establish mechanisms for decision making and overall control of activities, or what is generally termed governance (Kale and Singh, 2009). Typical governance mechanisms include (1)

joint ownership, in which the partners share control of some or all assets, (2) contracts that specify the rights and obligations of partners, (3) informal agreements that rely on trust and goodwill, or (4) some combination of these (Puranam and Vanneste, 2009).

Research to date does not suggest that any one of these mechanisms is superior, but rather that it is important to match a governance approach to the particular needs of a collaborative effort. Informal agreements may work effectively, for example, when the partners know each other well and activities are not complex or do not involve a high degree of risk. In any case, establishing a governance mechanism may be rocky because organizations are reluctant to grant authority to others or to sacrifice their own autonomy. It is thus critical that managers ensure that initial efforts and programs are responsive to partners’ needs, in order to build their commitment to collaboration.

Collaboration projects of any form vary in the extent to which their partners are willing to commit resources to initiate and sustain programs and activities. An important weakness of many projects is their inability to gain adequate commitment of partners’ resources (D’Aunno and Zuckerman, 1987). For example, there may be “free-rider” problems, in which some members of collaborations make little commitment, yet benefit from the investments of others. It is likely that such problems are directly proportional to the value that members perceive in committing resources to a project. The more value that members perceive in active participation, the more resources (including relinquishing autonomy) they are willing to commit to a project.

Of course, this leads to a challenging “chicken and egg” dilemma. On one hand, partners increase their commitment in proportion to threats from their environment and a particular partnership’s ability to reduce those threats and uncertainty. On the other hand, to be effective in meeting members’ needs, a partnership requires the investment of valued resources from members as well as members’ willingness to coordinate efforts with each other. At some point, collaboration requires an investment of resources by partners who have no certainty of return equal to their investment. At this point, trust becomes particularly important (D’Aunno and Zuckerman, 1987).

Recent studies suggest that alliance capabilities are also important antecedents for success, mediating the effects of experience (Heimeriks and Duysters, 2007; Schilke and Goerzen, 2010). These capabilities include the ability to manage

- contract design (Argyres and Mayer, 2007; Reuer and Arino, 2007);

- interorganizational coordination (Schreiner et al., 2009);

- coordination of several alliances simultaneously (Hoffmann, 2007);

- interorganizational learning (Kale and Singh, 2007); and

- change processes (Schilke and Goerzen, 2010).

Follow-Up Issues

Many challenges in this phase result from ineffective management of key issues early in the life of a partnership. One important example comes from a study by Judge and Dooley (2006), who analyzed factors associated with both opportunistic behavior and alliance performance in the U.S. health care industry. Opportunistic behavior consists of actions primarily driven by one’s own interest without regard for the interest of one’s partners. These researchers found that partner trustworthiness and contractual safeguards were negatively related to opportunistic behavior, which was negatively related to alliance performance. In other words, alliances where sufficient contractual safeguards are in place, and where trust exists between partners, see less opportunistic behavior from individual partners and stronger alliance performance. Trust was found to have a stronger impact on opportunistic behavior than contractual safeguards.

LEADERSHIP COMPETENCIES FOR IMPLEMENTING ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE3

I argue that using the techniques outlined in the above checklist (Box D-1) and overcoming barriers to effective collaboration is one of the defining challenges for leaders. The critical role of leadership has been largely neglected in prior work, which has focused mainly on the technical aspects of launching and managing mergers, alliances, and joint ventures, or, more often, their outcomes.

Though formal strategic assessment and planning are important elements of effective collaboration (see Box D-1), a far more challenging task is implementing change in organizations once a direction has been selected. Over the past two decades, research has explored the relationship between leadership characteristics or behaviors and organizational change (for reviews, see Bass, 1999; Conger and Kanungo, 1998; House and Aditya, 1997; Yukl, 1999, 2006). There is growing evidence that individuals’ leadership characteristics and behaviors influence the success or failure of organizational change initiatives (see, e.g., Berson and Avolio, 2004; Bommer et al., 2005; Eisenbach et al., 1999; Fiol et al., 1999; Gentry and Leslie,

__________________

3 This section of the paper, which examines leadership competencies for organizational change, draws heavily from a useful article by Battilana and colleagues (2010), which reports results from a study of leadership and organizational change in the English National Health Service (which I directed from 2002 to 2006).

2007; Higgs and Rowland, 2000, 2005; House et al., 1991; Howell and Higgins, 1990; Nadler and Tushman, 1990; Struckman and Yammarino, 2003; Waldman et al., 2004).

Most of the leadership studies that examine the relationship between leadership and change do not, however, account for the complexity of intraorganizational processes (Yukl, 1999), including the complexity of the organizational change implementation process. The fact that planned organizational change implementation involves different activities in which leadership competencies might play different roles has largely been ignored by the leadership literature (Higgs and Rowland, 2005).

In contrast, the literature on organizational change addresses the complexity of the change process (for a review, see Armenakis and Bedeian, 1999; Van de Ven and Poole, 1995) as well as the role of managers in various change implementation activities (e.g., Galpin, 1996; Judson, 1991; Kotter, 1995; Lewin, 1947; Rogers, 1962). Yet, an implicit common assumption of most of these studies is that leaders already possess the requisite competencies, skills, and abilities to engage in the different change implementation activities.

Effective Leadership for Planned Organizational Change

Notwithstanding a multitude of concepts that leadership researchers have advanced (for a review, see House and Aditya, 1997), there is general agreement that the task-oriented and person-oriented behaviors model (Bass, 1990; House and Baetz, 1979; Stodgill and Coons, 1957) remains an important foundation for managerial leadership (Judge et al., 2004). Of all the leadership competencies that are likely to influence organizational change, the ability to (1) provide effective direction for tasks (i.e., effectiveness at task-oriented behaviors), and (2) effectively engage followers (i.e., effectiveness at person-oriented behaviors) are among the most important (Nadler and Tushman, 1999).

Task-oriented skills are those related to organizational structure, design, and control, and to establishing routines to attain organizational goals and objectives (Bass, 1990). These functions are important not only for achieving organizational goals, but also for developing change initiatives (House and Aditya, 1997; Huy, 1999; Nadler and Tushman, 1990; Yukl, 2006).

Person-oriented skills include behaviors that promote collaborative interaction among organization members, establish a supportive social climate, and promote management practices that ensure equitable treatment of organization members (Bass, 1990). These interpersonal skills are critical to planned organizational change implementation because they enable

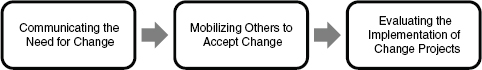

FIGURE D-2 Three key activities for effective organizational change.

leaders to motivate and direct followers (Chemers, 2001; van Knippenberg and Hogg, 2003; Yukl, 2006).

Effectiveness at task- and person-oriented behaviors requires different, but related, sets of competencies. Effectiveness at task-oriented behaviors hinges on the ability to clarify task requirements and structure tasks around an organization’s mission and objectives (Bass, 1990). Effectiveness at person-oriented behaviors, on the other hand, relies on the ability to show consideration for others as well as to take into account one’s own and others’ emotions (Gerstner and Day, 1997; Graen and Uhl-Bien, 1995; Seltzer and Bass, 1990). Managers might be effective at both task- and person-oriented leadership behaviors, or they might be effective at only one or the other, or perhaps at neither. Managers need a mix of leadership competencies for effectively leading planned organizational change.

Leaders undertake specific activities to implement planned organizational change projects (Galpin, 1996; Judson, 1991; Kotter, 1995; Lewin, 1947; Rogers, 1962); mistakes in the execution of any of these activities or efforts to bypass some of them are detrimental to the progress of change (Armenakis and Bedeian, 1999). Prior conceptual and empirical work (Armenakis et al., 1999; Burke and Litwin, 1992; Ford and Greer, 2005; Galpin, 1996; Judson, 1991; Kotter, 1995; Lewin, 1947; Steers and Black, 1994) recurrently emphasizes three key activities associated with successful implementations of planned organizational change: communicating, mobilizing, and evaluating (see Figure D-2). Communicating refers to activities leaders undertake to make the case for change and to share their vision of the need for change with followers. Mobilizing refers to actions leaders undertake to gain coworkers’ support for and acceptance of the enactment of new work routines. Evaluating refers to measures leaders employ to monitor and assess the impact of implementation efforts and to institutionalize changes.

Communicating the Need for Organizational Change

To destabilize the status quo and paint a picture of the desired new state for followers, leaders must communicate the need for change. Organiza-

tion members need to understand why behaviors and routines must change (Fiol et al., 1999; Kotter, 1995). Resistance to change initiatives is partly attributable to organization members’ emotional reactions, stemming, for example, from threats to self-esteem (Nadler, 1982), confusion and anxiety (Kanter, 1983), or stress related to uncertainty (Olson and Tetrick, 1988).

Leaders skilled at interpersonal interaction are able to monitor and discriminate among their own and others’ emotions, and to use this information to guide thinking and action (Goleman, 1998; Salovey and Mayer, 1990). They are able to recognize and leverage their own and others’ emotional states to solve problems and regulate behaviors (Huy, 1999). In the context of planned organizational change, consideration for others makes them likely to anticipate the emotional reactions of those involved in the change process and to take the required steps to attend to those reactions (Huy, 2002; Oreg, 2003). They are likely to emphasize communication of why the change is needed and to discuss the nature of the change and thereby reduce organization members’ confusion and uncertainty.

In contrast, leaders who are effective at task-oriented behaviors are organizational architects (Bass, 1985, 1990). Rather than communicating the need for change, task-oriented leaders are likely to concentrate their energies on developing the procedures, processes, and systems required to implement planned organizational change. Because they are also more likely to keep psychological distance from their followers, task-oriented leaders may be less inclined to put emphasis on communicating activities (Blau and Scott, 1962).

Mobilizing Others to Accept Change

During implementation, leaders must mobilize organization members to accept and adopt proposed initiatives into their daily routines (Higgs and Rowland, 2005; Kotter, 1995; Oreg, 2003). Mobilizing is made difficult by participants’ different personal and professional objectives and thus different outlooks on the initiative. Organization members who have something to gain will usually rally around a new initiative; those who have something to lose resist it (Bourne and Walker, 2005; Greenwood and Hinings, 1996).

The objective of mobilizing is to develop the capacity of organization members to commit to, and cooperate with, the planned course of action (Huy, 1999). To do this, leaders must create a coalition to support the change project (Kotter, 1985, 1995). Creating such a coalition is a political process that entails both appealing to organization members’ cooperation and initiating organizational processes and systems that enable that cooperation (Nadler and Tushman, 1990; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1997). Mobilizing thus entails both person- and task-oriented skills.

Securing buy-in and support from the various organization members can be an emotionally-charged process (Huy, 1999). Person-oriented leaders show consideration for others and are good at managing others’ feelings and emotions (Bass, 1990). They value communication as a means of fostering individual and group participation, and explicitly request contributions from members at different management levels (Vera and Crossan, 2004). Effective communicators and managers of emotions can marshal commitment to an organization’s vision and inspire organization members to work toward its realization (Egri and Herman, 2000). Their inclination to take others into account makes them more likely to pay attention to individuals’ attitudes toward change and to anticipate the need to involve others in the change process.

Mobilizing also implies redesigning existing organizational processes and systems in order to push all organization members to adopt the change (Kotter, 1995; Tushman and O’Reilly, 1997). For example, if a leader wants to implement a new system of quality improvement but does not change the reward system accordingly, organization members will have little incentive to adopt the new system. Redesigning existing organizational processes and systems to facilitate coalition building requires task-oriented skills.

Leaders who are effective at task-oriented behaviors are skilled in designing organizational processes and systems that induce people to adopt new work patterns (Bass, 1990). Their focus on completing tasks leads them to identify the different stakeholders involved in the change effort and to build systems that facilitate their involvement. Because they focus on structure, systems, and procedures, task-oriented leaders are more likely to be aware of the need to put in place systems that facilitate people’s rallying behind new objectives. As skilled architects, they are also more likely to know how to redesign existing organizational processes and systems in order to facilitate coalition building.

Evaluating the Implementation of Change Projects

Finally, leaders need to evaluate the extent to which organization members are performing the routines, practices, or behaviors targeted in the planned change initiative. As champions of the organization’s mission and goals, leaders have a role in evaluating the content of change initiatives and ensuring that organization members comply with new work routines (Yukl, 2006). Before the change becomes institutionalized, leaders need to step back to assess both the new processes and procedures that have been put in place and their impact on the organization’s performance.

Leaders who are highly skilled at social interaction might be more likely to have a positive attitude toward change projects and to view change as a positive challenge (Vakola et al., 2004). Their own positive feelings and

attitudes toward change might lead these leaders to overestimate the success and impact of the planned change project and thus fail to invest the required time and resources in objectively assessing the process, progress, and outcomes. To avoid dissonance, they might be reluctant to engage in a process of evaluation that could contradict their positive perception of the change (Bacharach et al., 1996).

Task-oriented leaders naturally tend to focus on the tasks that must be performed to achieve the targeted performance improvements (Bass, 1990). Their attention to structure and performance objectives attunes them to the attainment of these objectives. They are both aware of the need to analyze goals and achievements and comfortable with the need to refine processes following evaluation.

APPLICATION TO HEALTH CARE STUDIES ON THE PROCESSES AND PRACTICES OF COLLABORATION

In this section, I apply the concepts, principles, and practices summarized above to interpret the results of studies of the processes of change in collaborative ventures in health care (see Table D-4). I examine results from studies of hospital and physician collaboration, using the three major categories of these projects discussed above.

Lessons from Collaboration Among Hospitals

Results from several studies show that certain initial changes in collaborative ventures among hospitals come quickly, relatively easily, and in sequence: (1) integration of management functions (e.g., finance and accounting, human resources, managed care contracting, quality assurance and improvement programs, and strategic planning), followed by (2) integration of patient support functions (e.g., patient education), and then (3) integration of low-volume clinical services (e.g., Eberhardt, 2001).

Integrating or consolidating larger-scale clinical services and closure of service lines typically encounters strong opposition—in many cases studied, clinical service integration did not occur at all. Similarly, some studies report little success at integrating the medical cultures of merged hospitals even after 3 years of effort. In short, substantial changes in core clinical services take a long time and success is not guaranteed, as conflicting interests often emerge among stakeholders.

Despite these difficulties, however, there are examples of successful collaboration in which contextual factors and change processes made important contributions. Specifically, results from several case studies show that creating a centralized decision-making authority promotes effective collaboration, especially to the extent that this authority can develop shared

| Technical Leadership Tasks | Best Practices |

| Plans and protocols for change are needed (see Box 5-2 in Chapter 5) | Blueprints are needed to manage complexity and promote due diligence and effective decision making by leaders of change (e.g., conducting thorough premerger assessment of potential partners) |

| Technical capacity building | Investment (time, money) is needed to build capacity for improved performance |

| Structures and systems to support change | Structures (especially incentives) and systems (especially information systems) are needed to promote change and to improve organizational performance |

| People-Focused Leadership Tasks | |

| External pressure | In most cases, external pressure/support for change increases both its speed and likelihood of success |

| Buy-in from all levels; critical role of central authority and shared vision | Support from top managers and leaders is essential, but buy-in is also needed from lower-level staff; a centralized group with authority for implementation of changes is critical, especially to develop a shared vision and goals for change |

| Communication | Communication is needed at all levels: What is the vision; why change is needed; what progress has been achieved |

| Role of physician leaders | Involvement of physician leaders, both formal and informal, in key decisions is critical to success |

| Managing tensions, trade-offs inherent in change | Involving physicians versus respecting their time for patient care; time needed to build trust versus frustration with slow progress; building stakeholder buy-in versus building technical capacity (especially when buy-in and trust are enhanced by demonstrated technical capacity and improved performance) |

| Core versus peripheral organizational features | Change in peripheral features of organizations, including management and support services, is easier to achieve than change in either core clinical services or organizational culture |

values and vision with which the partner organizations learn to identify (Bazzoli et al., 2004). Further, support from top managers is critical, but should be complemented by buy-in from lower levels. This requires a great deal of communication within and across levels of hierarchy. Finally, at least one study identified strong and continuous external pressure on the partner organizations as a key to promoting the integration of clinical services.

Lessons from Collaboration Among Physician Groups

Coddington et al. (1998) provide a useful case study of the early stages of change that focus on bringing physician partners together. The key phases are (1) establishing trust, (2) assessing the fit between the relative strengths of the organizations, (3) assessing the ability to deliver a high-quality product, (4) developing a business strategy, and (5) considering effects on competitive position. Similarly, Robinson (1998) emphasized the importance of fit and relative strengths of partners in bringing them together.

In general, results from studies of collaboration among physician groups emphasize the importance of managing trade-offs and tensions involved in organizational change, for example,

- involving physicians versus respecting their time for patient care;

- slowly building trust versus frustration with slow progress; and

- building stakeholder buy-in versus building technical capacity (especially when buy-in and trust are enhanced by demonstrated technical capacity and improved performance).

Lessons from Hospital-Physician Collaboration

Given the importance of hospital-physician collaboration and the obvious potential for complications, a relatively large number of process studies have focused on these relationships. A major observation is the importance of developing a climate for change within the partner organizations. In turn, the role of physician leadership is universally noted as critical in developing a supportive climate for change; physician involvement is needed in both governance and management decisions. Results also highlight the importance of putting in place structures (such as incentives) and systems (especially information systems) to support changes in organizational processes and culture. As noted above, investment in management, clinical technologies, and core competencies matters, as do shared vision and values.

The work of Devers and colleagues (1994) stands out for its development of a three-part framework for assessing the extent to which consolidations achieve (1) functional integration (business and management

activities, noted above), (2) physician-system integration (alignment of incentives and physician involvement in decision making), and (3) clinical integration (e.g., common protocols). They find much functional integration but little integration in the other areas—a result similar to that for collaboration among hospitals. The results are discouraging, but it appears that external context can promote change—pressure from capitation and regulation, in particular, are related to more effective integration.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

I have several concluding observations about the outcomes associated with collaboration among health care organizations and best practices for improving these outcomes. First, there is considerable variation in the outcomes of collaborative ventures, regardless of the criteria one uses to assess their performance. Many, if not most, of these ventures fail to meet expectations in either the health care or the non–health care fields. An exception to this result is hospital mergers, which seem to improve members’ financial performance, though not necessarily to societal advantage; available evidence indicates that improved performance comes mainly from increased market power rather than efficiency from gains.

Second, the financial performance of hospital mergers appears to be stronger than results obtained from other forms of collaboration. Mergers typically involve more centralization of authority compared with other collaborative ventures, such as alliances, and this may be an important factor in their relative success.

Third, mergers are more costly than alternatives for the organizations (and communities) involved, at least in terms of initial time and money needed to launch and implement them. Yet, one could argue that the risk involved in mergers seems to pay off for the hospitals themselves, though not uniformly, given the variation that researchers observe in their performance.

Fourth, given substantial variation in their performance and relatively weak overall outcomes for many collaborative ventures, researchers and practitioners have begun to identify best practices for leading the processes involved in their implementation. Though results to date are useful, there is much more work to be done; for example, though I presented a relatively thorough checklist of best practices for implementing collaborative ventures (see Box D-1), few studies have examined the use of many of these practices in combination.

Fifth, the best available evidence indicates that it is useful to conceive of these practices from the perspective of three phases or stages: (1) precollaboration activities, (2) transition work, and (3) follow-up efforts. Further, these practices focus primarily on either technical tasks (e.g., due diligence with respect to antitrust issues, development of strategic plans, and devel-

opment of systems and incentives for change and improved performance) or people-oriented tasks (e.g., communicating effectively, involving key stakeholders, overcoming resistance to change) (see Box D-1). Prior studies indicate that leaders need skills for both technical and people-oriented tasks and, importantly, that failure to address both sets of tasks hinders implementation and performance (Battilana et al., 2010).

Sixth, in general, the literature on collaboration and change among health care organizations has not given as much attention to the role of leadership as it should. To be sure, the importance of involving physicians in leadership roles is typically noted, but more fine-grained analyses are lacking (Gilmartin and D’Aunno, 2007). I argue that effective leaders will communicate the need for change, mobilize others to accept changes, and evaluate implementation to make needed adjustments and promote optimal outcomes. Further, though leaders need skills in both technical and people-oriented tasks to be effective, many individuals lack this combination of skills, requiring the need for training or team approaches to leading change.

Finally, relatively fragmented and narrow disciplinary approaches have hindered both research and practice in this area. For example, the vast majority of studies of hospital mergers focus on financial performance (Vogt and Town, 2006), with little attention given to other key outcomes, such as access to care, and, similarly, with little attention to leadership using the concepts and principles discussed above. Promoting more effective collaboration in health care will require a broader, interdisciplinary approach. Indeed, it is likely that current collaborative ventures among health care organizations may face greater challenges than in the past due to the increased complexity of the organizations themselves, including, for example, the difficulty of integrating their information technologies. The current state of practice does not augur well for implementation of the ACA in general or accountable care organizations in particular—a type of organization that depends heavily on collaboration across organizational boundaries.

REFERENCES

Alexander, J. A., and M. A. Morrisey. 1988. Hospital-physician integration and hospital costs. Inquiry 25(3):388–401.

Anand, B. N., and T. Khanna. 2000. Do firms learn to create value? The case of alliances. Strategic Management Journal 21(3):295–315.

Argyres, N. S., and K. J. Mayer. 2007. Contract design as a firm capability: An integration of learning and transaction cost perspectives. Academy of Management Review 32(4):1060–1077.

Armenakis, A. A., and A. G. Bedeian. 1999. Organizational change: A review of theory and research in the 1990s. Journal of Management 25(3):293–315.

Armenakis, A., S. Harris, and H. Field. 1999. Paradigms in organizational change: Change agent and change target perspectives. In Handbook of organizational behavior, edited by R. Golembiewski. New York: Marcel Dekker. Pp. 631–658.

Bacharach, S., P. Bamberger, and W. Sonnenstuhl. 1996. The organizational transformation process: The micropolitics of dissonance reduction and the alignment of logics of action. Administrative Science Quarterly 41(3):477–506.

Bass, B. M. 1985. Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press. Bass, B. M. 1990. Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M. 1999. Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 8(1):9–32.

Battilana, J., M. J. Gilmartin, M. Sengul, A.-C. Pache, and J. Alexander. 2010. Leadership competencies for planned organizational change. Leadership Quarterly 21(3):422–438.

Bazzoli, G. J., S. M. Shortell, N. Dubbs, C. Chan, and P. Kralovec. 1999. A taxonomy of health networks and systems: Bringing order out of chaos. Health Services Research 33(6):1683–1717.

Bazzoli, G. J., C. Chan, S. M. Shortell, and T. D’Aunno. 2000. The financial performance of hospitals belonging to health networks and systems. Inquiry 37(3):234–252.

Bazzoli, G. J., L. M. Manheim, and T. M. Waters. 2003. U.S. hospital industry restructuring and the hospital safety net. Inquiry 40(1):6–24.

Bazzoli, G. J., L. Dynan, L. R. Burns, and C. Yap. 2004. Two decades of organizational change in health care: What have we learned? Medical Care Research and Review 61(3):247–331.

Bazzoli, G. J., S. M. Shortell, and N. L. Dubbs. 2006. Rejoinder to taxonomy of health networks and systems: A reassessment. Health Services Research 41(3 Pt 1):629–639.

Berson, Y., and B. J. Avolio. 2004. Transformational leadership and the dissemination of organizational goals: A case study of a telecommunication firm. Leadership Quarterly 15(5):625–646.

Blau, P. M., and W. R. Scott. 1962. Formal organizations. San Francisco: Chandler.

Bommer, W. H., G. A. Rich, and R. S. Rubin. 2005. Changing attitudes about change: Longitudinal effects of transformational leader behavior on employee cynicism about organizational change. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26(7):733–753.

Boukus, E., A. Cassil, and A. S. O’Malley. 2009. A snapshot of U.S. physicians: Key findings from the 2008 Health Tracking Physician Survey. Data Bulletin No. 35, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, DC.

Bourne, L., and D. Walker. 2005. Visualizing and mapping stakeholder influence. Management Decision 43(5):649–660.

Burke, W., and G. Litwin. 1992. A causal model of organizational performance and change. Journal of Management 18:523–545.

Burns, L. R. 1997. Physician practice management companies. Health Care Management Review 22(4):32–46.

Burns, L. R., and R. W. Muller. 2008. Hospital-physician collaboration: Landscape of economic integration and impact on clinical integration. Milbank Quarterly 86(3):375–434.

Burns, L., and D. Thorpe. 1997. Physician-hospital organizations: Strategy, structure and conduct. In The organization and management of physician services: Evolving trends, edited by R. Conners. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing.

Capps, C. 2005. The quality effects of hospital mergers. Unpublished manuscript.

Cartwright, S., and R. Schoenberg. 2006. Thirty years of mergers and acquisition research: Recent advances and future opportunities. British Journal of Management 17(S1):S1–S5.

Casalino, L. P. 2006. The Federal Trade Commission, clinical integration, and the organization of physician practice. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 31(3):569–585.

Chemers, M. M. 2001. Leadership effectiveness: An integrative review. In Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Group processes, edited by M. A. Hogg and R. S. Tindale. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Clement, J. P., M. J. McCue, R. D. Luke, J. D. Bramble, L. F. Rossiter, Y. A. Ozcan, and C. W. Pai. 1997. Strategic hospital alliances: Impact on financial performance. Health Affairs 16(6):193–203.

Coddington, D. C., K. D. Moore, and R. L. Clarke. 1998. Capitalizing medical groups: Positioning physicians for the future. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Conger, J. A., and R. N. Kanungo. 1998. Charismatic leadership in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cuellar, A. E., and P. J. Gertler. 2005. How the expansion of hospital systems has affected consumers. Health Affairs 24(1):213–219.

Damschroder, L. J., D. C. Aron, R. E. Keith, S. R. Kirsh, J. A. Alexander, and J. C. Lowery. 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 4:50.

D’Aunno, T., and H. S. Zuckerman. 1987. A life cycle model of organizational federations: The case of hospitals. Academy of Management Review 12(3):534–545.

Devers, K. J., S. M. Shortell, R. R. Gillies, D. A. Anderson, J. B. Mitchell, and K. L. Erickson. 1994. Implementing organized delivery systems: An integration scorecard. Health Care Management Review 19(3):7–20.

Dranove, D., and R. Lindrooth. 2003. Hospital consolidation and costs: Another look at the evidence. Journal of Health Economics 22(6):983–997.

Dranove, D., A. Durkac, and M. Shanley. 1996. Are multihospital systems more efficient? Health Affairs 15(Spring):100–103.

Eberhardt, J. L. 2001. Merger failure: A five year journey examined. Healthcare Financial Management 55(4):37–39.

Egri, C. P., and S. Herman. 2000. Leadership in the North American environmental sector: Values, leadership styles and contexts of environmental leaders and their organizations. Academy of Management Journal 43:571–604.

Eisenbach, R., K. Watson, and R. Pillai. 1999. Transformational leadership in the context of organizational change. Journal of Organizational Change Management 12(2):80–89.

Fiol, C. M., D. Harris, and R. House. 1999. Charismatic leadership: Strategies for effecting social change. Leadership Quarterly 10(3):449–482.

Ford, M., and B. Greer. 2005. The relationship between management control system usage and planned change achievement: An exploratory study. Journal of Change Management 5(1):29–46.

Galpin, T. 1996. The human side of change: A practical guide to organization redesign. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Gaynor, M. 2006. What do we know about competition and quality in health care markets? Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics 2(6):441–508.

Gentry, W. A., and J. B. Leslie. 2007. Competencies for leadership development: What’s hot and what’s not when assessing leadership-implications for organizational development. Organizational Development Journal 25(1):37–46.

Gerstner, C., and D. Day. 1997. Meta-analytic review of leader member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology 82(6):827–844.

Gilmartin, M. J., and T. D’Aunno. 2007. Leadership research in health care: A review and roadmap. Academy of Management Annals 1:387–438.

Goleman, D. 1998. Working with emotional intelligence. London: Bloomsbury.

Graen, G., and M. Uhl-Bien. 1995. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multilevel multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly 6(2):219–247.

Greenwood, R., and C. R. Hinings. 1996. Understanding radical organizational change: Bringing together the old and the new institutionalism. Academy of Management Review 21(4):1022–1054.

Hansen, M. T. 2009. Collaboration: How leaders avoid the traps, create unity, and reap big results. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Harrison, T. D. 2011. Do mergers really reduce costs? Evidence from hospitals. Economic Inquiry 49(4):1054–1069.

Hawley, A. H. 1950. Human ecology. New York: Ronald Press.

Hayford, T. B. 2011. The impact of hospital mergers on treatment intensity and health outcomes. Health Services Research 47(3 Pt 1):1008–1029.

Heimeriks, K. H., and G. Duysters. 2007. Alliance capabilities as a mediator between experience and alliance performance: An empirical investigation into the alliance capability development process. Journal of Management Studies 44(1):25–49.

Higgs, M., and D. Rowland. 2000. Building change leadership capability: The quest for change competence. Journal of Change Management 1(2):116–130.

Higgs, M., and D. Rowland. 2005. All changes great and small: Exploring approaches to change and its leadership. Journal of Change Management 5(2):121–151.

Ho, V., and B. H. Hamilton. 2000. Hospital mergers and acquisitions: Does market consolidation harm patients? Journal of Health Economics 19(5):767–791.

Hoang, H., and F. T. Rothaermel. 2005. The effect of general and partner-specific alliance experience on joint R&D project performance. Academy of Management Journal 48(2):332–345.

Hoffmann, W. H. 2007. Strategies for managing a portfolio of alliances. Strategic Management Journal 28(8):827–856.

House, R. J., and R. N. Aditya. 1997. The social scientific study of leadership: Quo vadis? Journal of Management 23(3):409–473.

House, R., and M. L. Baetz. 1979. Leadership: Some empirical generalizations and new research directions. Research in Organizational Behavior 1:341–423.

House, R. J., W. D. Spangler, and J. Woycke. 1991. Personality and charisma in the U.S. presidency: A psychological theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly 36(3):364–396.

Howell, J. M., and C. A. Higgins. 1990. Champions of technological innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly 35(2):317–341.

Huy, Q. 1999. Emotional capability, emotional intelligence and radical change. Academy of Management Review 24(2):325–345.

Huy, Q. 2002. Emotional balancing of organizational continuity and change: The contribution of middle managers. Administrative Science Quarterly 47:31–69.

Judge, T. A., R. F. Piccolo, and R. Ilies. 2004. The forgotten ones? The validity of consideration and initiating structure in leadership research. Journal of Applied Psychology 89:36–51.

Judge, W. Q., and R. Dooley. 2006. Strategic alliance outcomes: A transaction-cost economics perspective. British Journal of Management 17(1):23–37.

Judson, A. 1991. Changing behavior in organization: Minimizing resistance to change. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell.

Kale, P., and H. Singh. 2007. Building firm capabilities through learning: The role of the alliance learning process in alliance capability and firm-level alliance success. Strategic Management Journal 28(10):981–1000.

Kale, P., and H. Singh. 2009. Management strategic alliances: What do we know now, and where do we go from here? Academy of Management Perspectives 23(3):45–62.

Kanter, R. M. 1983. The change masters. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kastor, J. A. 2001. Mergers of teaching hospitals in Boston, New York, and Northern California. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Kerr, E. A., B. S. Mittman, R. D. Hays, A. L. Siu, B. Leake, and R. H. Brook. 1995. Managed care and capitation in California: How do physicians at financial risk control their own utilization? Annals of Internal Medicine 123(7):500–504.

Kerr, E. A., B. S. Mittman, R. D. Hays, B. Leake, and R. H. Brook. 1996. Quality assurance in capitated physician groups. Journal of the American Medical Association 276(15):1236–1239.

King, D., D. Dalton, C. Daily, and J. Covin. 2004. Meta-analyses of post acquisition performance indications of unidentified moderators. Strategic Management Journal 25:187–200.

Kotter, J. 1985. Power and influence. New York: Free Press.

Kotter, J. 1995. Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review 73(2):59–67.

Kralewski, J. E., T. D. Wingert, and M. H. Barbouche. 1996. Assessing the culture of medical group practices. Medical Care 34(5):377–388.

Kralewski, J. E., E. C. Rich, T. Bernhardt, B. Dowd, R. Feldman, and C. Johnson. 1998. The organizational structure of medical group practices in a managed care environment. Health Care Management Review 23(2):76–96.

Kralewski, J. E., W. Wallace, T. D. Wingert, D. J. Knutson, and C. E. Johnson. 1999. The effects of medical group practice organizational factors on physicians’ use of resources. Journal of Healthcare Management 44(3):167–183.

Kralewski, J. E., E. C. Rich, R. Feldman, B. E. Dowd, T. Bernhardt, C. Johnson, and W. Gold. 2000. The effects of medical group practice and physician payment methods on costs of care. Health Services Research 35(3):591–613.

Krishnan, R. A., S. Joshi, and H. Krishnan. 2004. The influence of mergers on firms’ product-mix strategies. Strategic Management Journal 25(6):587–611.

Lewin, K. 1947. Frontiers in group dynamics. Human Relations 1:5–41.

Luke, R. D. 2006. Taxonomy of health networks and systems: A reassessment. Health Services Research 41(3 Pt 1):618–628.

Macneil, I. R. 1983. Values in contract: Internal and external. Northwestern University Law Review 78(2):340–418.

Madison, K. 2004. Hospital-physician affiliations and patient treatments, expenditures, and outcomes. Health Services Research 39(2):257–278.

Marks, M. L., P. H. Mirvis, and L. F. Brajkovich. 2001. Making mergers and acquisitions work: Strategic and psychological preparation. Academy of Management Executive 15(2):80–94.

Modern Healthcare. 2012. 18th annual hospital mergers and acquisitions report. January 28. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20120128/DATA/120129989# (accessed April 2, 2012).

Nadler, D. A. 1982. Managing transitions to uncertain future states. Organizational Dynamics 11:37–45.

Nadler, D. A., and M. L. Tushman. 1990. Beyond the charismatic leader: Leadership and organizational change. California Management Review 32(2):77–97.

Nadler, D. A., and M. L. Tushman. 1999. The organization of the future: Strategic imperatives and core competencies for the 21st century. Organizational Dynamics 28(1):45–60.

Olson, D. A., and L. E. Tetrick. 1988. Organizational restructuring: The impact of role perceptions, work relationships and satisfaction. Group and Organization Studies 13(3): 374–389.

Oreg, S. 2003. Resistance to change: Developing an individual differences measure. Journal of Applied Psychology 88(4):680–693.

Pettigrew, A. M., R. Woodman, and K. Cameron. 2001. Studying organizational change and development: Challenges for future research. Academy of Management Journal 44(4):697–713.

Pfeffer, J., and G. R. Salancik. 1978. The external control of organizations. New York: Harper and Row.

Puranam, P., and B. S. Vanneste. 2009. Trust and governance: Untangling a tangled web. Academy of Management Review 34(1):11–31.

Reuer, J. J., and A. Arino. 2007. Strategic alliance contracts: Dimensions and determinants of contractual complexity. Strategic Management Journal 28(3):313–330.

Robinson, J. C. 1998. Consolidation of medical groups into physician practice management organizations. Journal of the American Medical Association 279(2):144–149.

Rogers, E. M. 1962. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press.

Salovey, P., and J. D. Mayer. 1990. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 9:185–211.

Schilke, O., and A. Goerzen. 2010. Alliance management capability: An investigation of the construct and its measurement. Journal of Management 36(5):1192–1219.

Schreiner, M., P. Kale, and D. Corsten. 2009. What really is alliance management capability and how does it impact alliance outcomes and success? Strategic Management Journal 30(13):1395–1419.

Seltzer, J., and B. M. Bass. 1990. Transformational leadership: Beyond initiation and consideration. Journal of Management 16(4):693–704.

Shah, R. H., and V. Swaminathan. 2008. Factors influencing partner selection in strategic alliances: The moderating role of alliance context. Strategic Management Journal 29(5):471–494.

Steers, R. M., and J. S. Black. 1994. Organizational behavior. New York: Harper Collins.

Stodgill, R., and A. E. Coons. 1957. Leader behavior: Its description and measurement. Columbus: Ohio University, Bureau of Business Research.

Struckman, C. H., and F. J. Yammarino. 2003. Organizational change: A categorization scheme and response model with readiness factors. In Research in Organizational Change and Development, edited by R. W. Woodman and W. A. Pasmore. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Trinh, H. Q., J. W. Begun, and R. D. Luke. 2010. Better to receive than to give? Interorganizational service arrangements and hospital performance. Health Care Management Review 35(1):88–97.

Tushman, M. L., and C. O’Reilly. 1997. Winning through innovation: A practical guide to leading organizational change and renewal. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.