5

Oral Health Literacy Programs

COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVE ON THE IMPORTANCE OF ORAL HEALTH LITERACY

Scott Wolpin, D.M.D. Choptank Community Health Center

Wolpin practices dentistry at the Choptank Community Health Center, a federally qualified health center located in a medically underserved area on the rural Eastern shore of Maryland. The health center includes eight doctors’ offices, three of them with dental offices. Each of the offices is about 30 miles away from the others. The center, with a staff of 140, provides primary care services in offices, schools, migrant camps, and a hospital. In 2011, the center had 85,000 visits and 15,000 of these visits were dental visits.

The clinic serves a low-income group of dental patients, many of whom are watermen or employees of the many poultry farms in the area. Many young children present to this clinic with dental or oral disease. In this community and elsewhere, disparities in oral health occur by socioeconomic status and race and ethnicity. Many of the children living in the area are state-insured and do not have a dental home. The clinic is participating in an environmental scan to better understand why effective preventive practices are not succeeding in the community.

A recent New York Times article described the use of general anesthesia to treat extensive dental disease in preschoolers.1 In Wolpin’s view,

_____________________

1“Preschools in surgery for a mouthful of cavities,” New York Times, March 6, 2012.

the rise in the number of children in need of such treatment is evidence of poor oral health literacy. Children with complex and extensive dental disease can often be treated in a clinic setting; however, if the disease is located in multiple quadrants of the mouth, treatment can be lengthy and challenging. Children are often in pain and they are scared. Children with severe behavioral problems usually need to be hospitalized and sedated, which is an approach as a last resort. In most cases, the need for hospitalization can be avoided with the use of prevention and early intervention strategies.

In the health center’s school-based oral prevention program, dental hygienists work in the 30 public schools in the 9-county area, providing preventive services and oral health education. The center’s philosophy is to bring services to the patients, because patients often have a difficult time accessing care at the center. When children are identified with untreated dental disease and they do not have an established dental home, they are referred to the closest center dental office. Children with extensive needs or children with special health needs may have to seek care at the local hospital.

The center’s patients represent 20 percent of the population, but have 80 percent of the community’s dental disease. The disease is often advanced and requires complex treatment. The patients have difficulty navigating the local health care system and case management services are used to facilitate appropriate care. Many of the patients have relatively low literacy skills and difficulty understanding how to enroll in or use Medicaid. For example, many of the pregnant women seen at the center do not take advantage of their Medicaid insurance. Some patients are not able to articulate their signs and symptoms of disease. Other problems arise because patients do not adhere to treatment recommendations. Wolpin said that this might be a sign of distrust of providers and described how many clients do not know when or how to ask questions about the treatment options that are present for them or for their children.

Wolpin provided an illustration of the impact of low oral health literacy. The center serves many Spanish-speaking migrant agricultural workers. These workers often live in multifamily dwellings. In order to assure that the working men of the household get a good night’s sleep, mothers will put babies to bed with a bottle of sweet liquid, or they will give babies a pacifier sweetened with honey. The result is that many of the children have early childhood caries, and have to be treated in a hospital.

Wolpin described his early approach to education as preaching. He accepted the need for the baby to have a bottle at bedtime, but asked mothers to fill the bottle with fluoridated water. His patients seemed to be in agreement with his advice during their visits, but did not change their behaviors. It is possible that they were not changing their behaviors

because they were afraid that the tap water was harmful. An interpreter brought this to Wolpin’s attention when he was working with a family. Some families, many of them poor, were buying bottled water. Wolpin could identify with this concern because when he visits other countries, he worries about the safety of the drinking water. However, in this case, a lack of knowledge about the safety of the water supply was harming both budgets and the dental health of young children in the community.

Wolpin described the worst case of dental caries in a child that he has ever treated. He had to remove all of the teeth of a 3-year-old. This child had to live without teeth until the permanent teeth fully emerged at about age 6 and, in the interim, it was very difficult for the child to eat. Surgeries in such cases are very expensive, as much as $1,500. If restorative work is completed, the cost of surgery can rise to $4,000. Yet, these cases and their associated costs are generally easily preventable.

The need for follow-up and wellness visits can also be misunderstood by parents who often only bring children in when there is extensive disease and symptoms.

Another clinical experience illustrates the need for clear communication. The family of a little girl who was having surgery for multiple caries was given preoperative directions. Because she would be treated in an operating room, she was to have nothing by mouth after midnight. Yet when she came to the presurgery room with her parents the next day for her parents to sign the general anesthesia consent the surgery had to be canceled because the child was eating a donut. The family understood that “nothing by mouth” meant that all of the girl’s teeth were going to be removed. They worried that she would be very hungry after the operation so they thought she needed to have something to eat in the morning. Wolpin pointed out that providers need to ensure that patients understand what is being said.

The environmental scan at the center included an informal interview with Wolpin and another center dental provider. The research team walked through the offices to evaluate the user-friendliness of the center. This provided excellent information for the center staff. The research team also examined the center’s printed materials to see if they were health literate-sensitive. Some of the centers patients were interviewed, and the interviews are ongoing. A mail survey is planned that will go out to dental providers and cover communication techniques.

Several important lessons resulted from the environmental scan process, Wolpin said. First, the dental community is not going to be able to adequately respond to the crisis in dental health in the community because there are too few dentists taking care of families with Medicaid insurance and those who are uninsured. In his view, the dental community needs to be able to rely on the medical community. With training,

medical providers can conduct dental risk assessments, offer preventive interventions, and link children with untreated dental disease with a dental home. Second, there is a need to know and practice according to current evidence-based science. It is just as important to ensure that patients and the public have this understanding and, in turn, want these interventions. One approach is to employ culturally appropriate lay health workers to provide oral health, nutrition information, dental sealants, and fluoride to underserved families. Messages need to be kept simple and use plain language.

Finally, training in health literacy for all dental staff is essential according to Wolpin. Support staff, hygienists, and assistants often have extensive interactions with patients. There are many opportunities to share messages throughout the clinic experience. Center staff working in school settings can be sensitive and share important messages in a health literate way.

ORAL HEALTH LITERACY: HOW CAN WE IMPACT VULNERABLE POPULATIONS?

Marsha Butler Colgate-Palmolive Company

Marsha Butler, vice president of global oral health at Colgate-Palmolive Company, discussed a children’s oral health promotion campaign that has been implemented globally, the Colgate Bright Smiles, Bright Futures program. The objectives of the program are to

- empower children to practice good oral hygiene;

- partner with government and the profession to improve oral health;

- help reduce prevalence of dental caries worldwide; and

- give back to communities where Colgate-Palmolive does business.

There is a long history of oral health education at Colgate-Palmolive, beginning in 1911 when there was a program for teachers, “Good Teeth and Good Health.” Since the 1940s, the company has provided oral health school-based programs globally. Colgate’s Bright Smiles, Bright Futures was launched in 1991 as a comprehensive oral health initiative targeted to the most vulnerable and underserved communities in the United States.

The Bright Smiles, Bright Futures program was initiated in recognition of the toll that oral disease was taking as the most prevalent health problem in the United States. Children from families who are poor and those who are members of racial and ethnic minority groups are known to

suffer disproportionately. The Surgeon General’s 2000 report, Oral Health in America, reported that 52 million school hours are lost annually due to oral health-related disease. The World Health Organization’s 2003 report concluded that good oral health is critical to the overall health. The 2007 Trends in Oral Health Status report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the following:

- Prevalence of dental decay increased in primary teeth from 24 percent in 1988-1994 to 28 percent in 1999-2004 (2-5 years old).

- Prevalence of dental decay in permanent teeth has decreased significantly during this period from 25 percent to 21 percent.

- Among non-Hispanic black youth, 6 to 8 years, dental decay has increased during this period from 49 percent to 56 percent.

A recent New York Times report (March 6, 2012) discussed an increase in the number of preschoolers with extensive dental disease requiring in-hospital treatment under general anesthesia. Interviews with some of the parents whose children were treated this aggressively suggested that they were not told basic information on how to address caries, when to go to the dentist, or when to start using fluoride toothpaste for very young children, 2 to 5 years old.

Butler cited the definition of oral health literacy from Healthy People 2010: “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services necessary to make appropriate health decisions” (HHS, 2000a) and enumerated some of the instructive findings from the health literacy literature:

- Thirty percent of U.S. parents have difficulty understanding and utilizing health information (Yin et al., 2009).

- Lower health literacy skills often lead to poorer health status, unhealthy behaviors, and poor health outcomes (Lee et al., 2011).

- Factors at both the individual and community level, such as socioeconomic status, age, sex, ethnicity, and health insurance coverage can affect the relationship between literacy and health outcomes (Butler, 2012).

- Self-efficacy and self-care can mediate the effect of health literacy on health status (Osborn et al., 2011).

The Bright Smiles, Bright Futures program in the United States is offered in schools and includes a curriculum for preschool through third grade. There is a teacher’s guide, audio-visual materials to engage the children, and parent communication materials that go home with each child. The goals of the program are to

- increase children’s knowledge of preventive oral health measures;

- increase understanding of nutritional foods and drinks for good oral health;

- instill proper oral hygiene skills for healthy teeth and gums;

- relate good health to high self-esteem;

- increase family awareness and knowledge of the benefits of oral health; and

- increase low-income family linkages to oral health providers.

It is important to develop children’s oral health consciousness so that they can have confidence about accepting responsibility for their personal oral care at the earliest possible age, Butler said. The program aims to modify oral health habits by using colorful, fun, and engaging multimedia and multicultural activities. An example is a comic book adapted from a program video.

The prekindergarten materials were developed in partnership with Head Start. The materials promote self-esteem and self-efficacy. With the program, Head Start teachers and health coordinators become advocates for good oral health. Parent involvement is an important critical part of the program. A program to prevent early childhood caries that targets pregnant women and caregivers with babies and toddlers, developed in collaboration with Early Head Start program, has been well-received by health coordinators, said Butler. A parent checklist simplifies CAMBRA2 recommendations from the University of California, San Francisco, in a colorful graphic with simple language that can be easily understood by Early Head Start parents (Figure 5-1). In addition to print materials, many Bright Smiles, Bright Futures resources are available online for both parents and children. There are games for children and materials for health educators.

Implementation studies have been conducted in collaboration with the University of Maryland. Results show that families believe the program taught students responsibility for their own oral health. Children exposed to Bright Smiles, Bright Futures relative to nonparticipants had increased knowledge of oral health, higher frequency of visits to the dentist, brushed their teeth morning and night, and had better brushing skills.

The Bright Smiles, Bright Futures program uses eight mobile vans to take the program to where children live, and where vulnerable populations reside. These mobile vans have traveled to more than 160 cities. The program operates in partnership with thousands of volunteer dental professionals to educate students and school staff, and refer children

_____________________

2CAMBRA stands for CAries Management By Risk Assessment.

to providers. Partner organizations include dental associations, dental schools, neighborhood health centers, and hospitals.

A partnership with the school of dentistry at the University of California, Los Angeles, takes oral health awareness to an infant care program. The program, led by Dr. Francisco Ramos-Gomez, provides counseling to patients with infants and toddlers at a community clinic. Materials are used that are designed to reach individuals of low literacy.

Raising the awareness of the community also benefits oral health. Bright Smiles, Bright Futures partners with national and local community-based groups, as well as religious, fraternal, and civic organizations in fun and engaging ways. The program participates in large community festivals and multicultural events. In addition, partnerships have been formed with the media and public relations groups to promote oral health literacy.

Colgate-Palmolive launched Hispanic Oral Health Month in partnership with the Hispanic Dental Association. This effort promotes awareness of oral health in Hispanic communities, using bilingual resources to educate families. A joint outreach effort in 12 Hispanic communities involves retailers, including pharmacy, community-based organizations, and Hispanic Dental Association volunteers.

A partnership has also been formed with Univision, a Spanish language multimedia company. This partnership has led to the integration of oral health information and education into Spanish programming. Oral health messages were incorporated into a reality television program, Nuestra Belleza Latina, that features young women who are competing to be on Univision television.

As part of a partnership with the Walmart Corporation, Bright Smiles, Bright Futures mobile dental vans visit participating Walmart stores to provide oral health education. Diagnostic screenings are available as are referrals for treatment. An online resource, “Building Smiles Together,” is available to Walmart customers. Participating Walmart stores are located throughout the country and some of them are in areas that do not have ready access to dental care and information.

Another campaign, “A Hundred Million Smiles,” builds awareness of oral health in ethnic and poor communities. “Brush-a-thons,” involving hundreds of young children brushing their teeth at the same time, raise awareness of oral hygiene. Partnerships have also been forged with Boys and Girls Clubs, YMCAs, and faith-based organizations. These partnerships provide opportunities to share the Surgeon General’s “Seven Steps to a Bright Smile,” which was created in partnership with the U.S. Public Health Service. Celebrities have also been recruited to serve as dental role models.

The Bright Smiles, Bright Futures program has reached more than 650 million children in 80 countries since 1994. The program’s materials

have been translated into 30 languages. There are in-school programs and Web-based interventions. Many collaborating countries, including Brazil and China, have been successful in raising oral health awareness. In China, 100 million children have been reached over a 10-year period, and thousands of teachers have been trained and educated through their nationwide oral health promotion program, “Love Thy Teeth.”

In a school-based program in South Africa, Mama Colgate, a nurse, goes into rural areas to educate families and children. A dental mobile van provides treatment and on the Phelophepa3 health train Colgate sponsors a dental car where nurses and dental students educate individuals in oral care in rural areas of South Africa.

In India, Colgate partnered with the Anganwadi rural program that uses primary health care workers to deliver primary health, nutrition, and education for children and mothers. This program operates in partnership with the Indian Government and targets mothers and children 3 to 6 years old in rural areas. Colgate provided training to the primary health care workers so that they could teach basic oral health. To date, Butler reported, 118,000 workers have been trained and several million children have been reached with simple educational materials, lectures, slide presentations, flipcharts, and materials.

Butler concluded by highlighting important lessons learned from Colgate’s many oral health initiatives. First, preventive oral health education and promotion represent significant steps toward achieving positive oral health outcomes. Second, partnership with local and community-based organizations is a critical component for success. Third, more research is needed to better understand the impact of grassroots approaches to promote oral health literacy at both the individual and community level.

DENTIST-PATIENT COMMUNICATION TECHNIQUES USED IN THE UNITED STATES: THE RESULTS OF A NATIONAL SURVEY

Gary Podschun American Dental Association

Podschun presented the results of a recent national survey sponsored by the American Dental Association (ADA) that was conducted among member and nonmember dentists in clinical practice to identify commu-

_____________________

3“South Africa’s custom-built ‘health train,’ Phelophepa I, delivers health services to -remote areas of the country, reaching over 180,000 patients a year” (http://www.southafrica.info/about/health/health-train-160312.htm [accessed October 10, 2012]).

nication techniques routinely used by dentists and how their use varied.4 The ADA is the professional association that represents the interest of dentists and also works to advance the oral health of the public.

Podschun acknowledged the contributions of the following groups and individuals who guided the design and execution of the survey:

- ADA National Advisory Committee on Health Literacy in Dentistry

- Dr. R. Gary Rozier, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Gillings School of Global Public Health

- Dr. Alice M. Horowitz, University of Maryland at College Park, School of Public Health

- Brad Petersen, ADA Health Policy Resources Center

- John Cantrell, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Gillings School of Global Public Health

The definition of oral health literacy adopted as ADA policy in 2006 is “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate oral health decisions.” This definition was adapted from a definition of health literacy formulated at a 2004 National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) workshop. An alternative definition, “the ability to access, understand, appraise, and communicate information to engage in the demands of health contexts to promote health,”5 is also an important continuation of the definition of health literacy. This definition takes into account the demands that are placed on the public by health care providers in the health care system.

The ADA has adopted policies acknowledging that limited health literacy is a possible barrier to oral disease management and that effective communication skills are essential to the practice of dentistry. Podschun added that the lack of communication skills of health professionals often impedes the public’s health literacy. Podschun noted that much effort has been devoted to the assessment and development of skills among patients and the public in health literacy, but very little attention has been paid to the development and testing of communication skills of dental and other health care professionals. Because of the lack of information about the communication skills of dentists, or about the dentist/patient communication interaction, the 5-year ADA Health Literacy in Dentistry

_____________________

4The results of the survey are published: R. G. Rozier, A. M. Horowitz, and G. Podschun. 2011. Dentist-patient communication techniques used in the United States: The results of a national survey. Journal of the American Dental Association142(5):518-530.

5This definition can be found in the article I. Rootman and B. Ronson. 2005. Literacy and health research in Canada: Where have we been and where should we go? Canadian Journal of Public Health 96(Suppl 2):S62-S77.

Action Plan 2010-2015 (ADA, 2009) calls for additional studies to assess the health communication perceptions and practices of dentists and their team members, including dental hygienists and dental assistants. The action plan also calls for the advancement of interventions for oral health professionals to improve their communication skills.

The purpose of the ADA survey was to (1) determine techniques used by dentists and dental team members to ensure effective patient communication and understanding; and (2) identify the variation in routine use of these techniques according to factors that might be targeted with interventions. In his presentation, Podschun focused on dentists. Data were collected for the entire dental team and he mentioned that there will likely be manuscripts developed describing the techniques used by dental team members.

Staff from the ADA survey center selected a simple random probability sample from approximately 179,594 member and nonmember professional active dentists (general and specialists) in the United States. Questionnaires were mailed to 6,300 sampled dentists and two mail and one telephone follow-ups were conducted to improve response rates.

The questionnaire included 86 items that were developed by the ADA National Advisory Committee on Health Literacy and Dentistry. The final questionnaire included 18 communication items for which participants indicated on a 5-point Likert scale, from never to always, how often during a typical work week they used certain techniques. The 18 questions covered the following five domains:

- Understandable language (5 questions)

- Teach Back method (2 questions)

- Patient-friendly materials (4 questions)

- Help understanding (5 questions)

- Patient-friendly environment (2 questions)

These communication techniques were recommended to the ADA by the American Medical Association (AMA) because they were included in an AMA survey of health providers (Schwartzberg et al., 2007). Major parts of the questionnaire were pilot tested with dental providers at the 2007 ADA annual meeting.

The primary outcome variable for the analysis was the count of routine techniques used by the dentists. Routine was defined as “most of the time” or “always” as opposed to “never,” “rarely,” or “occasionally.” Predictor variables that were listed in the analysis included the following:

- Provider characteristics (i.e., age, race/ethnicity, sex, U.S.-born/trained)

- Practice characteristics (i.e., patient characteristics, specialty, primary occupation, setting)

- Health literacy awareness

- Training in communication techniques

- Barriers to patient understanding (i.e., “none,” “lack of time,” “awkward,” “can’t simplify language any more,” “patient language,” “patient non-adherence”)

- Practice-level change

- Outcome expectancy (18-item scale: low, medium, high)

Podschun explained the nature of the last item listed, outcome expectancy. As part of the survey, dentists were asked whether they thought each of the 18 communication techniques were effective. A scale was created by summing the yes responses to each of the 18 techniques. A categorical variable, called outcome expectancy, was created based on the variable’s distribution (i.e., low, medium, high). Outcome expectancy includes both one’s confidence in performing the task, as well as, the expectation that the task will actually have the intended outcome.

Podschun mentioned that because the intent of the survey was to understand providers’ communication practices, the analysis was limited to dentists who were involved in clinical care. A number of analyses were conducted:

- Count of routine use of techniques (e.g., “most of time” and “always” vs. “never,” “rarely,” and “occasionally”)

- Comparison of mean number of techniques used routinely, by predictor variables (analysis of variance)

- Confirmation of association of predictor variables with number of techniques used routinely with regression analysis (ordinary least squares regression)

Two hundred and ninety-two of the 6,300 mailed questionnaires could not be delivered, leaving an eligible sample of 6,008. Of the eligible sample, 2,010 dentists returned their questionnaires for an overall response rate of 33.4 percent. The analytical sample included 1,994 dentists because 16 dentists were excluded who reported that they were not involved in clinical care any longer. Most questionnaires had complete answers (the item response rate was 87.1 percent).

Table 5-1 shows results for each of the items within the five domains of techniques. Podschun reported that less than one-quarter of dentists routinely used any of the techniques listed in the patient-friendly practice or teach-back method domains such as referring patients to the Internet or asking patients to repeat information or instructions back to them.

He pointed out that interpersonal communication and the teach-back method are considered by literacy experts as basic skills that every provider should use routinely. He described the other skills enumerated in Table 5-1 as additional techniques that are useful, particularly for those with limited health literacy.

The three techniques grouped within the patient-friendly domain were among the least frequently used. The five assistance techniques were among the most frequently used techniques by the dentists. The use of materials and aids were very popular strategies among the dentists surveyed, with printed materials and models or X-rays being two of the top three reported techniques used. The five interpersonal communication techniques were also among those techniques identified as basic. Of the

TABLE 5-1 Dentists’ Routine Use of Oral Health Literacy Techniques

| Technique | Percent Routinely Used |

| Patient friendly | |

|

1. Ask patients how they learn best |

4.9 |

|

2. Refer patients to Internet |

11.1 |

|

3. Use interpreter |

15.3 |

| Teach back | |

|

4. Ask patient to repeat information or instructions* |

16.0 |

|

5. Ask patient to tell you what they will do at home to follow instructions* |

23.5 |

| Assistance | |

|

6. Underline key points in printed materials |

31.5 |

|

7. Follow up by phone to check understanding |

35.1 |

|

8. Read instructions out loud |

48.1 |

|

9. Ask staff to follow up on post-care instructions |

53.3 |

|

10. Write or print out instructions |

54.5 |

| Materials | |

|

11. Use video or DVD |

15.8 |

|

12. Hand out printed materials |

65.9 |

|

13. Use models or X-rays to explain |

73.1 |

| Communication | |

|

14. Present only 2 or 3 concepts at a time* |

29.8 |

|

15. Ask family member or friend to participate* |

34.3 |

|

16. Draw or use pictures* |

42.5 |

|

17. Speak slowly* |

67.8 |

|

18. Use simple language* |

90.6 |

NOTE: Techniques indicated by a * are considered basic techniques.

SOURCE: Podschun, 2012.

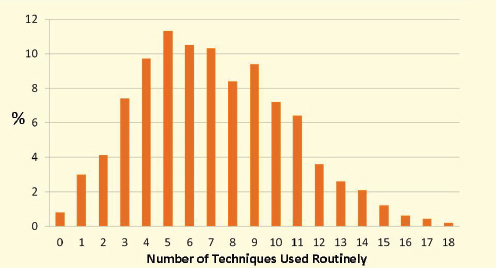

FIGURE 5-2 Percent of dentists and number of techniques used.

SOURCE: Podschun, 2012.

18 techniques, use of simple language was the most commonly reported strategy.

The highest number of communication techniques was reported by dentists who were either ages 36 to 45, black, female, and/or born outside or received their professional education outside the United States.

Figure 5-2 illustrates the number of dentists and the number of techniques used by the dentists. Podschun reported that only about one-third of the dentists used as many as one half of the techniques. Dentists reported routinely using an average of 7.1 of the 18 techniques and 3.1 of the techniques that were identified as basic.

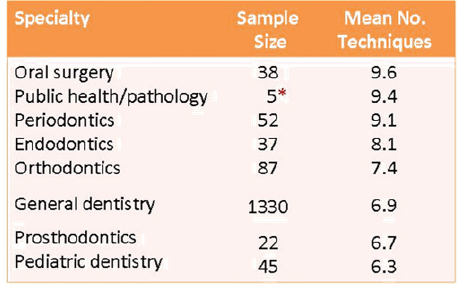

As shown in Figure 5-3, with the exception of pediatric dentists, specialists were more likely to use more techniques than general dentists. The average number of techniques used by oral surgeons (9.6 techniques)—the highest users of the techniques—was significantly higher than those used by pediatric dentists (6.3 techniques) and general dentists (6.9 techniques)—the professionals who used the least number of techniques.

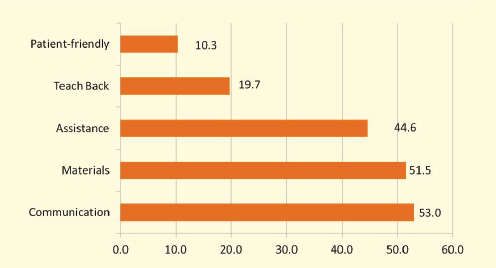

Figure 5-4 shows that the frequency of the use of the 18 techniques varied considerably across the five domains of techniques. This figure illustrates the average for each domain.

Podschun discussed how variables that measured some aspect of health literacy awareness, communication training, outcome expectancy, barriers, and practice-level change were also associated with the number of techniques used. One of the strongest predictors within this group of

FIGURE 5-3 Practice characteristics and differences in mean numbers of techniques used.

NOTE: © American Dental Association, All Rights Reserved.

*Small sample size does not provide accurate estimate.

SOURCE: Podschun, 2012.

FIGURE 5-4 Percent of techniques used routinely.

SOURCE: Podschun, 2012.

variables was outcome expectancy. Dentists classified as having high outcome expectancy were routinely using 50 percent more techniques than those dentists classified as having low outcome expectancy.

Dentists reported that they thought an average of 11.7 of the 18 techniques and 4.8 of the 7 basic techniques were effective. The results of the regression analysis generally confirmed these findings.

Podschun described some of the limitations of the survey. First, he mentioned that the list of 18 techniques included in the survey was drawn primarily from medicine to measure communication techniques. Although the list reflects guidance about important communication techniques, the response scale was not tested for validity or reliability.

Second, there may have been reporting bias. The type and quality of communication could have been better determined by direct observation. Third, he stated that nonresponse bias could have influenced the findings. The response rate of 33.4 is low, but typical for a mailed survey of practicing health professionals. Lastly, Podschun discussed the lack of information on the quality of communication techniques used by the sampled dentists. He indicated that future studies are needed to assess this aspect of dentist/patient communication. The number of techniques needed might differ depending on how well they are performed.

Podschun summarized the four main findings of the survey:

- The number of communication techniques used routinely varies greatly among dentists.

- The routine use of techniques was similar to physicians, nurses and pharmacists for 10 of 14 techniques examined in both studies (Schwartzberg, 2007).

- The ideal number and type of communication techniques that should be used when communicating with dental patients are not known, but the results of the survey suggested that dentists’ routine use of these techniques is less than what is needed to meet the oral health needs of all patients.

- There was limited use of the techniques recommended by health literacy experts and two-thirds of dentists use fewer than four of the seven basic techniques.

Podschun discussed recommendations that follow from the survey results. He stated that the dental profession needs to develop and disseminate communication guidelines and programs, such as continuing education courses and toolkits for practicing dentists and their team members. In his view, to advance dentist-patient communication effectiveness, oral health literacy tools need to be developed with a multidisciplinary research agenda. Lastly, Podschun stated that policies and

programs need to be implemented to assure that graduating dental care professionals and dentists already in practice are meeting the information needs of all their patients.

ORAL HEALTH AND PRIMARY PREVENTION

Matt Jacob Pew Children’s Dental Health Campaign

Jacob described the work of the Pew Charitable Trusts in the area of oral health prevention. The Pew Children’s Dental Health Campaign was launched in 2008. It is one of many projects that are a part of the Pew Center on the States where there is a focus on state-based change and reform. Because so much of oral health policy is determined through state law and state regulation, it is appropriate for there to be a state-based focus on this issue.

Jacob discussed ongoing work on community water fluoridation. To lay the groundwork for their project, Pew several years ago attempted to ascertain what, if anything, the public thought about community water fluoridation and how issues related to water fluoridation were playing out in different communities. Phone surveys and several focus groups were conducted. In addition, online bulletin boards were created in an attempt to capture the segment of society without landline phones. In-depth interviews with oral health advocates were conducted in four communities: Wichita, Kansas; York, Pennsylvania; San Diego, California; and Palm Beach County, Florida. Each of those four communities had had a fairly intense fluoridation debate play out in the previous 4 to 5 years.

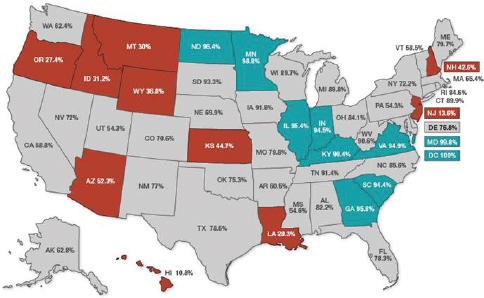

As background, Jacob, showed a map illustrating the penetration of fluoridated water across the United States (Figure 5-5). As of 2008, an estimated 74 million Americans on public water systems lacked access to optimally fluoridated water. The 10 states shown in orange/red are the worst states in terms of access to fluoridated water. Jacob reiterated that the map only refers to people whose homes are connected to public water systems. Millions of Americans live in rural areas where they rely on well water or other sources that are not fluoridated to the optimal level that prevents decay. The 10 states shown in teal green, many of them in the mid-Atlantic region, are the 10 best states in terms of access to fluoridated water.

Jacob described the contentious nature of water fluoridation projects. Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1946 was the first community to initiate water fluoridation. A group called the John Birch Society claimed that this proposal was a communist plot. This controversy subsided and many communities subsequently opted for fluoridated water systems. Tremendous

FIGURE 5-5 Penetration of fluoridated water systems.

SOURCE: Jacob, 2012.

progress has been made, according to Jacob. The progress was largely the result of a strategy that Jacob referred to as the “tiptoe” approach. Such an approach might involve quietly approaching a sympathetic city council member or a county commissioner to see if they would float a proposal to fluoridate the public water system. Next, a pediatrician or a dentist would be called on to testify. The goal was to bring the measure to a vote of the council or commission without the kind of loud, contentious public debate that could delay action for months or even years. According to Jacob, this “tiptoe” approach was quite successful. It has not been the approach used everywhere. In some areas, the issue was dealt with at the state level through state laws and state mandates. However, in many cases water fluoridation was considered a local community issue where this “tiptoe” approach worked quite well.

This approach, however, has had some unintended negative consequences for oral health literacy. Jacob reported results from a 2010 survey of Maryland residents. Despite the fact that Maryland is the most comprehensively fluoridated state in the country, almost 6 of 10 Marylanders could not identify why fluoride is adjusted or added to public drinking water. And according to a Pew-sponsored survey, 80 percent of Americans said that they were only somewhat informed, or not at all informed, about the issue of fluoridation. According to pollsters, when this many people

report being somewhat informed, or not at all informed, the proportion of the uninformed in the population is probably even higher.

On the surface, Jacob stated that promoting water fluoridation should be relatively easy. This is not an intervention where people need to be coaxed to come into dental offices. It does not involve trying to decide where to locate clinics. And yet, Jacob said, the one thing that has complicated the dynamic of community water fluoridation is that this issue, unlike other areas of dental health, has an opposition. According to Jacob, relatively few people oppose water fluoridation but these individuals are persistent, similar to the opposition organized around vaccines. Unfortunately, they have placed erroneous information about water fluoridation on the Web, he said.

According to Jacob, one of the weaknesses of the conventional approach described above to initiating water fluoridation (i.e., the “tiptoe” approach) is that it does not work well in an era when opponents can place such erroneous information on the Web. Furthermore, the conventional approach does nothing to build public understanding and buy-in. The conventional approach, to a large extent, bypassed the public. Jacob acknowledged that there are some excellent educational resources available to educate the public about water fluoridation, for example, the American Dental Association’s Fluoridation Facts (http://www.ada.org/sections/newsAndEvents/pdfs/fluoridation_facts.pdf). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also has excellent Web resources on fluoridation that help people understand that it is safe and effective.

One of the findings of the Pew focus groups is that how the question of water fluoridation is framed is critically important. Jacob stated that if the conversation begins with a discussion of fluoride, support for fluoridation is likely to be more lukewarm. However, if the issue is put into the larger context of protecting teeth, individuals are more likely to positively view fluoridation.

Jacob cited a technology guru, James McGovern, who said, “a solution needs a problem. If the people required to change do not perceive there is a problem . . . you will never convince them to change.” As Jacob sees it, fluoridation is a solution to a problem. Establishing the problem is crucial before the public and policy makers can be convinced that fluoridation deserves their support.

Jacob described further polling work conducted in Oregon. Pew’s poll tested five messages to see how they affected existing support. The Oregon poll showed that the majority of the public supported fluoridating the water supply. The Pew group wanted to see what messages could be effective in strengthening the intensity of support among existing supporters. Five very different messages are shown in Table 5-2. Of these

TABLE 5-2 Results of Pew’s Oregon Survey Designed to Test Messages That Would Bolster Support for Water Fluoridation

| How Messages Affect Existing Support | Much More | Somewhat More | No Effect |

| More than 35% of children in Oregon have untreated dental disease. | 60% | 26% | 12% |

| The CDC has called fluoridation 1 of the “10 great public health achievements of the 20th century.” | 39% | 36% | 21% |

| Studies prove that fluoride prevents and can even reverse the process of tooth decay. | 47% | 35% | 13% |

| Communities have a moral obligation to ensure that all residents benefit from fluoride—something that is proven to improve oral health. | 31% | 36% | 20% |

| The typical city saves $38 for every $1 invested in water fluoridation. | 47% | 38% | 11% |

SOURCE: Jacob, 2012.

five messages, the first, which is a statement of the problem, received an uptick in support.

To build public awareness, Jacob stated that it is critical to frame the issue of water fluoridation in the context of oral health. Pew is one of at least 30 organizations that have partnered to launch the Campaign for Dental Health. Its associated website is iLikeMyTeeth.org. Other partners include the American Academy of Pediatrics, the California Dental Association, and Voices for America’s Children. Jacob indicated that the website represents an effort to reclaim some of the World Wide Web for accurate information on fluoridation.

Jacob pointed out that the use of clinical language can backfire. Sodium fluoride is a chemical, but there is no need to refer to it as such. The use of such technical terms can needlessly scare people and play into the fear-based arguments used by fluoridation opponents. When a mother of a 3-year-old hears the word “chemical,” she does not feel reassured.

Dental sealants are another prevention strategy that Pew supports, viewing sealants as a very cost-effective strategy to prevent caries. Sealants prevent 60 percent of decay at one-third of the cost of filling a cavity.

And yet, Jacob reported in 2010 seven states had no school-based sealant programs to reach at-risk children. This represents a concern to the Pew Children’s Dental Campaign, because without such programs, it will be difficult for states to reach the goal of Healthy People 2020, to increase the proportion of children aged 6 to 9 years who have received dental sealants on one or more of their permanent first molar teeth.

Building awareness in this area is vital according to Jacob. He cited a 2010 study indicating that parents’ low level of health literacy was linked to a lower rate of sealant use by children (Mejia et al., 2011). Jacob reported that roughly 20 states have rules restricting sealant application that do not reflect the latest clinical evidence.

Although public awareness is crucial in this area, the Pew campaign has decided to focus their efforts on policy makers, state dental boards, and others that are shaping this issue. It is important for them to be aware of the latest clinical evidence and to understand that certain barriers, such as prior exam rules, can actually make it more difficult to deliver care to those who need it. Pew has plans to release a 50-state report card mid-2012 that focuses on prevention and emphases issues related to dental sealants.

The Pew report will grade all 50 states based on their policies to

- alleviate unnecessary barriers to reaching more kids with sealants;

- increase the percentage of high-risk schools with sealant programs;

- participate in the National Oral Health Surveillance System (NOHSS); and

- meet the sealant goals in Healthy People 2010.

On the last indicator, the report will document states’ progress toward meeting the Healthy People 2010 goal because if states are behind on the 2010 goal, then they are probably not on track for meeting the Healthy People goals for 2020.

Pew is also very interested in the third indicator: participation in the NOHSS. Jacob pointed out that if data are not collected and reported, there is little information on how a state is doing, where problems reside, and the scope of problems.

Chairman Isham opened the discussion with an observation about the status of water fluoridation in the United States. Isham was stunned to learn that 74 million Americans are without access to fluoridated water. He observed that Minnesota has a high rate of water fluoridation and neighboring Wisconsin does too. In Wisconsin, the rural hospitals in one

county determined that the fluoridation of water is a major issue and have gotten together with the public health department to develop strategies to preserve or initiate water fluoridation.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires that hospitals quantify their community benefit in order to maintain their community benefit designation under the tax code. Hospitals have to conduct a community-based needs assessment. Hospitals are encouraged to conduct these assessments with their public health partners and then report on how they spend their community benefit money.

Isham observed that there are opportunities for partnership between hospitals and public health systems to meet the IRS requirements regarding community benefit. He also pointed out that there are lost opportunities in terms of collaboration between dentistry and primary care. He noted that the Institute of Medicine recently released a report on public health and primary care. Isham scanned the report to see if there was coverage of dentistry or health literacy. Dentistry appeared twice, and health literacy did not appear in the report.

Isham noted that much of the controversy surrounding water fluoridation stemmed from the public’s perceptions of the role of government. If the issue is reframed in terms of the health of children, and the economic vitality of communities, then water fluoridation might have a more favorable appeal to the broader American public. Isham noted that the dental and oral health community has a tremendous role to play in starting this conversation.

Conicella suggested that the anti-fluoridation movement is a sign of health illiteracy. She asked the panel if members of this movement communicate with Pew, the ADA, or the states with their concerns about water fluoridation. If so, she asked how the oral health community is responding to their concerns. Jacob replied that Pew and its national partners received many e-mails in response to their Campaign for Dental Health and their website, ilikemyteeth.org. However, Jacob said, most of these e-mails were sent by a small group of anti-fluoride activists. Jacob mentioned the similarities between the anti-vaccine movement and the anti-fluoridation movement. Isham said that there are many opportunities for organizations to leverage their assets for educating the public and identified the different levels of intervention that are needed to meet the oral health literacy challenge. He noted that attention needs to be paid to both consumers and to policy makers.

Roundtable member Brach asked Podschun if there were oral health specific tools and resources available through the ADA, and if there were, if materials had been adapted from medical health tools and resources. Podschun said that the National Advisory Committee on Health Literacy and Dentistry recommended at their last meeting that a health literacy

toolkit be developed. In their review of what that toolkit might look like, they discussed the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) toolkit and the possibility of tailoring sections of that resource to the practice of dentistry.

Podschun said that the National Advisory Committee on Health Literacy and Dentistry discussed the development of an awareness-raising video targeting dentists and their team members. He stated that the American Medical Association found that the production of a health literacy video and its distribution to all of their members was the single most important factor in raising the consciousness of their member physicians. Podschun said that a similar approach might be useful in raising awareness of ADA members and others about the importance of oral health literacy.

Podschun pointed out that printed materials and brochures are the most often used educational strategies in dental practices and yet there is no assessment of the quality of those materials. The ADA would like to develop a rapid assessment tool that dental practices could use to assess the quality of the materials that they are purchasing for their offices. Brach mentioned that AHRQ is in the process of developing a health information rating system.

Ross asked Podschun about the interaction between race and literacy. He noted that the ADA survey results showed that dentists with low-outcome expectancies used fewer health literacy techniques. Ross asked, “Why did they have such low outcome expectancies? Was there some cultural bias inherent in the survey?” He further asked if it was possible to control for cultural competence in the analysis of the survey. Podschun clarified the survey results by pointing out that African American dentists and foreign-born dentists were more likely to use more health literacy techniques.

Roundtable member McGarry asked Jacob if Pew has analyzed the responses to the website that has been created. Jacob responded by pointing out that the website is a fairly nascent effort launched in November 2011. He described a major task relating to SEO (Search Engine Optimization). These are techniques to improve search rankings. Traffic to the ilikemyteeth.org site has grown slowly. A number of partners, including the AAP, the California Dental Association, and a variety of state and local foundations are supporting the Campaign for Dental Health and its Web presence.

Pew and its partners who launched the Campaign for Dental Health have learned how to optimize its website ranking. For example, the amount of content on a website influences whether searchers are directed to a particular site. The Campaign for Dental Health has hired consultants to assist with their Web development to ensure that it is accessible. The

Campaign has encouraged state health departments to link into the site. Links to Web content that include “.gov” improve a site’s standing. These strategies are important because a website may have excellent content, but if no one is directed to it by Web browsers, it is not going to have an impact. In Jacob’s judgment, the anti-fluoridation movement has done a very good job of giving their content the veneer of science.

Roundtable member Pearson observed that health literacy and oral health literacy have followed a similar trajectory as a field in its development phase. The initial work often involves designing evaluation and research programs to identify where problems exist in the community. He observed that such an orientation leads to “sick care,” which in turn leads to a continuing focus on treatment. This can make it difficult to change the system’s orientation to focus on prevention and integrative medicine. It may be that oral health literacy, because it is a younger field, may avoid this difficulty. He asked the panel members if they could imagine what research and evaluation tools and then intervention campaigns might look like if they focused on what works instead of what does not work. He asked, “How might that orientation change your strategy and possibly the outcomes?”

Jacob responded that with his background in messaging and public relations, it is important to focus on problems. He pointed out that every single day in America, hundreds of airplanes land safely and you never hear about it on the news and no one discusses it over coffee because it is not a problem. Problems tend to generate concern and get people talking. He suggested that there are ways to frame oral health problems in such a manner that it does not have a treatment focus. The Campaign for Dental Health does highlight the problem of tooth decay in America, but the focus is on fluoridation and sealants as preventive strategies to address the problem.

Roundtable member McGarry noted that there is a growing body of research on the association between oral health and chronic diseases. He asked the panel whether they had observed this association in their practices or research. Wolpin, from his clinical experience, highlighted the important interface between oral health care and medical care. He sees patients with difficult to manage diabetes with dental abscesses. These patients are at higher risk of infection because of their poorly controlled diabetes. Wolpin described a vicious cycle between the uncontrolled diabetes and infection. He stated that it is critically important for dental providers to work collaboratively with medical colleagues. The relatively new focus on the patient-centered medical home provides opportunities to take a transdisciplinary approach to health care. In Wolpin’s community health center, the medical staff helps him gain access to the youngest children, because they are generally seen for well-child visits five times

the first year of life. This provides opportunities for anticipatory guidance and risk assessment. There are also opportunities for transdisciplinary approaches among older patients, according to Wolpin. If a medically underserved adult seeks dental care for a toothache, Wolpin is able to refer those with high blood pressure to his medical colleagues.

Roundtable member Ratzan asked the panel how to better integrate oral health literacy with broader prevention issues. In response, Horowitz, indicated that multiple approaches are needed. One very important approach is to have medical school curricula that include oral health issues. For too long, the disciplines have been separated and they should not be, in her view. Continuing education courses and training are also needed to reach those who have completed their education.

Horowitz added that having electronic records also fosters integration. County health departments and federally qualified health centers that have electronic records are able to cross-communicate. And when different services are provided under one roof, it is much easier to collaborate. Some facilities house medical and dental services and, in addition, have WIC and Head Start offices. A well-educated workforce and public are also essential to integration according to Horowitz.

Wolpin described innovative partnerships between academia and community health centers that provide opportunities for service learning. His community health center has an advanced education in general dentistry residency program. The dental residents shadow a primary care provider, so they learn about medicine.

Rush asked Wolpin to describe the content of the training that is provided to his staff on health literacy. Using excellent resources is key to a good training program according to Wolpin. When working with the WIC programs and the school-based programs, Wolpin has relied on tools similar to those developed for the Bright Smiles, Bright Futures campaign. Unfortunately, there is not a central and indexed resource for materials related to best practices. Consequently, finding good resources to share with the center’s staff is sometimes difficult. Wolpin has found that sharing anecdotal experiences can be a powerful way to convey the relevance and importance of health literacy.

Wong asked the panel whether “positive deviant models” have been applied to oral health literacy. Here, individuals in the community who show positive deviance from the norm, in this case, children with good teeth or no cavities, are studied to see if their parents (or the children themselves) have identifiable practices that could be disseminated more effectively. Wong asked if there are examples of parents who are doing things differently and effectively, thereby keeping their children free from dental disease and away from the dental office. In reply, Butler discussed some of the ongoing research at Colgate-Palmolive. Best practices and

effective prevention programs are being examined in the United States and around the world to identify the ingredients of program success. These analyses include estimates of the potential to improve oral/dental outcomes as a result of programs that have incorporated education and the use of effective preventive treatments. Children and families who have adopted best practices are included in these reviews. Butler stated that the results are forthcoming and, when available, will be widely shared.

Wolpin in response to Wong’s questions added that it is important to understand the motivations behind noncompliant behavior on the part of parents. There is an assumption that when families do not seek care for their children, they do not value oral health care. Wolpin pointed out that parents need to understand the importance of dental care before they can value it. Providing education to families is key to changing behavior.

Roundtable member Patel asked Wolpin if his community health center had an electronic health record that would allow him to track oral health patterns within the community he serves. In addition, she asked whether the electronic record, if present, is the same system used for dental and medical care. Wolpin replied that the center has an electronic health record, but it lacks sophistication. At present it is used primarily for completing the dental charting and clinical notes. In terms of record sharing with primary care, Wolpin stated that their record system is not integrated. The joint assessments that are done within the community health center are paper-based or e-mail/task correspondence. The records are not shared or colocated. Additionally, dentists are not yet utilizing diagnosis codes and this makes tracking oral health patterns more difficult.

Brach asked Wolpin what systematic changes were made at the health center as a result of his participation in the oral health literacy environmental scan conducted there. She also asked how other health centers that are not participating in a research study could identify shortcomings and find resources to assist them in addressing oral health literacy. Wolpin said that the intervention allowed him to rise above the focused perspective of a dentist and take a broader look at the meaning of his clinical experiences. This broader perspective allowed him to answer questions, such as why aren’t my patients getting healthier? Why aren’t they getting the message? In terms of systematic changes that have taken place at the clinic, the most important in his view has been raising awareness about oral health literacy and its link to patient outcomes among the staff. The center’s consent forms have been rewritten in plain language. Other changes to the center are in progress. Wolpin said that he is working with the National Network of Oral Health Access. This network represents a tremendous resource for community health centers. The center is in the process of obtaining tools and resources to augment the adoption of best practices. Horowitz added that the environmental scan process had just

begun and it may be too early to expect systematic change within the center.

Pisano asked Wolpin how to address resistance on the part of some oral/dental providers to the idea that oral health literacy is important to the health of their patients. Wolpin said that a focus on outcomes would help overcome resistance. Most providers want to excel. If shown the evidence that addressing oral health literacy issues improves clinical outcomes, providers would become sensitized to the issue. In his view, monitoring clinical performance is a powerful tool to bring about changes in clinicians’ behavior. Finding out that a colleague has better outcomes following the adoption of oral health literacy practices could motivate change.

Roundtable member Humphreys asked Butler how the materials developed for the Bright Smiles, Bright Futures campaign had to be adapted for use in different countries. She also asked whether the materials are available in multiple languages.

Butler replied that an expert board was convened from around the world to initially develop the materials. This group identified needs, gaps, and challenges. Local adaptations to the materials took place once the program was launched in a country. The materials have been translated into at least 30 languages. In India, the materials have been translated into 10 local languages and adapted to reflect urban and rural issues. The materials developed for use in the United States are available on the U.S. website in English and Spanish. Materials developed for other countries are available on local websites.

Humphreys discussed the great demand for good materials in languages other than English in the United States. The U.S. population is very diverse, and often, extended members of a family can only communicate in a foreign language. Humphrey suggested that Colgate-Palmolive consider making the Bright Smiles, Bright Futures materials that are available in so many languages available to practitioners in the United States. Butler agreed that this was a good idea.

Roundtable member Pleasant observed that there is general agreement on the benefits of applying what has been developed in health literacy to the oral/dental health field. He asked if there are findings or interventions that have been developed within the oral/dental health community that should be adopted by the health literacy community. Horowitz explained that oral health literacy research is a relatively new area, and not as well developed a field as general health literacy. She indicated that it is too early to tell if there are unique insights to convey from health literacy. There is a growing body of literature in oral health literacy and eventually, it may be appropriate for AHRQ to support an evidence-based review on this topic.

Horowitz added that oral health literacy should be a part of general health literacy. These areas have distinct foci, but should be integrated. Practices that are recommended in health literacy should be applied to oral health literacy. Butler agreed with Horowitz and added that it is important to look at oral health as a part of overall health. In practice, pediatric providers are essential in recognizing oral/dental issues early and ensuring that referrals to dental providers occur.

Roundtable member Schyve commented that much of the workshop focused on getting information to consumers and ensuring their understanding of the information. He asked the panel how rewards or incentives that are necessary to actually change behavior and create new habits could be incorporated into oral/dental interventions. Schyve noted that there are several habits that the public should adopt, for example, brushing, flossing, drinking fluoridated tap water, using tap water in the bottle at bedtime, eating healthy snacks, and making regular dental visits. Schyve’s question about incentives was prompted by his reading of a recent book by Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. According to Schyve, this book describes three antecedents to behavior change: people need a cue, they need to take action, and then they need a reward for the action. Schyve noted that in the area of oral/dental care, there are few, if any, immediate rewards. For example, there are no immediate rewards for brushing your teeth. However, Duhigg in his book uses Pepsodent as a case study. To motivate people in the early days to adopt the habit of brushing their teeth, Pepsodent promoted the idea that people would be happier after brushing their teeth because the film on their teeth that had accumulated overnight would be gone after brushing. This campaign was apparently successful in getting people to start brushing their teeth with toothpaste.

In reply, Horowitz suggested that incentives or rewards would likely have to vary for different groups, based on age and other factors. The avoidance of pain and financial cost could be considered rewards, but in some cases, these may not be immediate rewards. At this point, there is strong evidence that many people simply do not have the knowledge or understanding that is needed to prevent tooth decay. They do not have the option to act without such understanding. She stated that with the knowledge and the tools necessary to act, people can be empowered to adopt healthy behaviors. She added that, in some communities, extreme financial barriers have to be overcome. Some parents cannot afford toothbrushes and toothpaste.

Roundtable member Loveland recounted her experience of taking a mobile van into communities to provide services to individuals with asthma. A major challenge was adequate staffing and record keeping. Without a physician on site, patients did not receive follow-up. In

response to this issue, Butler stated that partnerships have been key to the success of their programs. The Colgate-Palmolive sponsored programs partner with community health centers and other practitioners to provide education and treatment services. These partnerships help build trust, and individuals receiving care have the opportunity to meet with local providers who might share some of their characteristics. The use of partnerships for the past 20 years has ensured the provision of care to the children served in the Colgate-Palmolive programs.

Roundtable member Alvarado-Little asked the panel how oral health professionals can create practice environments that engender trust. Most patients need to feel comfortable before they are able to ask questions of their providers, especially if there are socioeconomic, cultural, or language barriers. In response, Wolpin described some progressive workforce models that involve mid-level dental providers. These providers are often from the same cultural background as the patients they serve. Another approach is to identify a “cultural broker” that can effectively communicate with clients and members of the oral/dental team. Wolpin found that many of the children who were having extensive dental procedures performed at his local hospital came from the same largely Spanish speaking small town. The mother of one of his patients became an oral health champion within the community. Case managers are also invaluable in terms of providing linkages to care. Case managers conduct environmental scans, identify barriers to care, and work with families to overcome these barriers. Horowitz agreed that case managers and health navigators are critical to facilitating appropriate care, especially among low-income groups. Butler added that involving community members in programs is key to success. Sometimes, the messenger is as important as the message.

Isham identified three themes from the workshop. First, there was a call for more integration of dental and medical care. Second, while it may be too early to tell what distinguishes oral health literacy from health literacy in general, the important focus at this time is on implementing evidence-based findings. Third, the incorporation of evidence-based practice into dental practice seems to be an issue.

Isham discussed the potential of integrated electronic medical records. HealthPartners has a large dental practice and a large dental plan. Its medical plan serves individuals covered by Medicaid and commercial insurance products. A common dental and medical record has been a challenge. And yet, the opportunity to address prevention across medical and dental care is tremendous. From Isham’s perspective, the dental profession can make progress in terms of developing measures of quality, coding and data systems, and monitoring systems.

Horowitz, identified a unique attribute of oral health literacy. She suggested that oral health is uniquely and summarily ignored. She observed

that new mothers are taught to bathe and clean the baby, except the mouth. She speculated that the neglect of oral/dental health stems from the fact that dental disease is often a silent disease. An arm infection cannot be ignored, but periodontal disease is often ignored. She indicated that the oral/dental health community may have to work even harder than the medical community to make progress. That said, Horowitz concluded that incorporating oral health messages into general health literacy is very helpful.

Wolpin described the evolution of dentistry during the past 20 years. He stated that 20 years ago it was common practice to provide everyone with cleanings and fluoride every 6 months. There was no risk-based approach to dentistry and no evidence to support the practice. In Wolpin’s view, dentistry is catching up with medicine in terms of practicing according to evidence and adopting health literacy principles.

Butler stressed the importance of integration, but expressed frustration that although we know what to do, we are not doing it. The tools are available, but many do not know where they are. In her view, there needs to be a pulling together of stakeholders. She suggested that this pulling together could occur as part of an online initiative, or perhaps through a collaborative development of materials that could be used by both health and dental providers. She added that it may be necessary to create a central resource, where information on oral health and its relationship to health could be easily accessed.

Isham brought to the group’s attention a report from the Commonwealth Fund on quality by hospital referral region across the country. The report discusses some very interesting variations in the quality of medical care. AHRQ has had state snapshots of quality of care as part of their national quality and disparity reports. Isham asked whether oral health issues are included in these studies. These comparative studies often engage communities and policy makers and can provide leverage points for change. Brach said that the AHRQ state snapshots and the National Health Care Quality and Disparities Report do include basic dental access information such as whether a child of a certain age has had a visit to the dentist in the past year. But, she said, until there are validated, reliable quality measures, AHRQ and others do not have material to include in these reports.

Isham raised an issue related to access to dental care. In Minnesota, there is a new profession referred to as “dental therapist” that has a very carefully defined scope of practice that includes education and prevention-related activities. The development of this new profession is in response to serious access problems, especially for individuals at lower socioeconomic levels. Wolpin commented that this area is very contentious and is being debated within the dental profession in the

United States. Isham acknowledged the controversial nature of this new profession, but wanted to be able to address the issue. He stated that throughout the day’s proceedings the problem of access to dental care among the traditionally underserved community was raised. There are clearly well defined remedies to many of the problems within this community. He asked if there are new ways to educate the public, to reach out and engage them.

Wolpin agreed that the model of care currently in place needs improvement and the dental profession may need to be pushed in order to bring about change. Many dentists have opted out of participating in the Medicaid and Medicare programs. He said that rewards for clinical outcomes may be necessary to change professional behavior. At the present time, he pointed out that a dentist benefits financially if he or she does more surgery. In Wolpin’s opinion, this reward system has to change. He suggested that incentives be put in place to keep people healthy. If financial incentives to encourage prevention were in place, then the private-sector dentistry community may change course. Wolpin added that dental care optimally is a partnership and the patient should be made to realize that there are benefits to prevention, in terms of cost savings and prevention of pain and suffering.

Horowitz added that there needs to be better access to primary prevention, rather than just treatment. Dental disease can be prevented and this is where attention needs to be focused. She said that the creation of a new dental profession such as the dental therapist will not address the problem unless the incentive structures are changed. Unless there are incentives for prevention, the emphasis on drilling our way out of this disease will not stop. Horowitz emphasized the need focus on prevention. She recommended starting with mothers and teaching them how to care for their children’s oral health needs. In her view, mothers are the first educator, the first doctor, and perhaps the first dentist.

With her international experience, Butler agreed that the focus needs to be on prevention. In her view, a model will emerge, the incentives will arise, and providers and payers will engage in change. From a global perspective, for example, the strategy of drilling your way out will not be effective in countries with few dentists per population. A focus on education and prevention is a beginning.

Ismail encouraged the workshop participants to move beyond reports with recommendations and urged the participants to act. He stated that one action that could improve oral health literacy is the development of a tool for the assessment of literacy and a list of interventions that have been proven to change environments and organizations. He added that perhaps accreditation standards could be augmented to include issues related to oral health literacy. In his opinion, this is an intervention that could greatly motivate change.