7

National Activities in Oral Health Literacy

NATIONAL ACTIVITIES IN ORAL HEALTH LITERACY, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

RADM William Bailey, D.D.S., M.P.H. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Limited health literacy is associated with poor health and negatively associated with the use of preventive services, management of chronic conditions, and self-reported health, Bailey said. He added that oral health literacy is positively associated with oral health status and quality of life, frequency of dental visits, and knowledge and understanding of preventive measures. In his view, health disparities can be reduced by empowering people and giving them the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic information. This will then allow them to be partners in their own health decisions. In short, Bailey stated, improvements in health literacy will ensure a healthier population.

Clear communication is essential, said Bailey. He recounted a joke in which a woman came into a grocery store and told the clerk that she needed 50 gallons of milk. The clerk asked the woman why she needed 50 gallons of milk. She explained that she had been to see a dermatologist for a skin condition and the dermatologist instructed her to take milk baths. The clerk asked if the milk needed to be pasteurized and she replied, no, just up to my chin. Bailey felt that this joke illustrates the complexity that underpins communication. He suggested that this complexity is magnified in the context of dental care, where there are strange noises and

smells and complex terminology is used. Dental patients may experience a range of emotions from mild apprehension to dread.

Bailey summarized some of the actions being taken by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with regard to health literacy, specifically those focusing on oral health literacy. He said that much has been accomplished across HHS in this area in just the past 2 years. The Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, addresses oral health literacy by incorporating health literacy into professional training, facilitating the movement of clients into Medicaid and CHIP programs, and establishing state-based insurance exchanges. Participating health plans and insurers are required to use clear, consistent, and comparable health information using a standardized template to describe plan coverage and benefits.

Bailey described how the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) provisions of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) call for adoption of electronic health records to provide health information that is meaningful and useful to consumers.

He then discussed the Plain Writing Act of 2010 that requires federal agencies to write documents clearly so that the public can understand and use them. This requirement does not just apply to health. It applies across the federal government to any information that the federal government is providing on federal benefits or services, or how to comply with federal regulations. Federal agencies are required by law to report on this requirement beginning in 2012. These reports will serve as the baseline for measuring future progress.

The HHS 2010 National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy involved more than 700 individuals and organizations. The seven goals of the plan focus on

- health information creation and dissemination,

- health care services,

- early childhood through university education,

- community-based services,

- partnership and collaboration,

- research and evaluation, and

- dissemination of evidence-based practice.

Bailey noted that the Affordable Care Act, the Plain Language Act, the HITECH provisions, and the HHS National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy provide a unified way to address health literacy goals and strategies. Bailey felt that these accomplishments provide a roadmap for progress. He stated that it is remarkable that these initiatives have all occurred within the past 2 years.

Bailey enumerated other milestones, for example, the development of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. The underlying concept here is that providers are not able to gauge the health literacy of patients so effective communication tools should be used with all patients. This follows the rationale for universal precautions that are used for infection control.

Bailey described the National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity along with the 2011 HHS Strategic Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. The action plan address health literacy; for example, it calls for an update of the 2009 national standards on culturally and linguistically appropriate services.

The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) in 2004 hosted a workshop on oral health literacy that examined a framework for studying relationships between oral health literacy and other points of intervention; summarized available evidence; identified research gaps; and provided a map for future work (NICDR, 2005).

Bailey described the oral health content of Healthy People 2010 and 2020. He said that the number of Healthy People communication objectives doubled from 2010 to 2020. The objectives address the need to measure system level changes in the areas of health literacy, including health care providers’ use of the teach-back method; the level of shared decision making between patients and providers; and population-wide access to personalized eHealth tools. The oral health objectives for 2010 included explicit language to promote oral health and prevent oral disease. The objectives stated that oral health literacy is necessary for all Americans. Bailey said that the Healthy People 2020 objectives lack this explicit statement, but in a background statement, there is a discussion of a person’s ability to access oral health being associated with factors such as education level, income, and race/ethnicity.

Bailey discussed the release in 2011 of two IOM reports. In the first report, Advancing Oral Health in America (2011a), the IOM committee recommended that all relevant HHS agencies undertake oral health literacy and education efforts aimed at individuals, communities, and health care professionals. The IOM committee recommended that communitywide public education on oral diseases and preventive interventions was needed, especially on the infectious nature of dental caries, the effectiveness of fluorides and sealants, the role of diet and nutrition in oral health, and how oral diseases affect other health conditions. The second recommendation of the IOM committee related to communitywide guidance on how to access oral health care with the focus on using websites such as the National Oral Health Clearinghouse and healthcare.gov. The third IOM recommendation pertained to professional education on best practices in patient-provider communication with the focus on how to communicate

to an increasingly diverse population about prevention of oral cancers, periodontal disease, and dental caries.

Bailey stated that needed action steps have been clearly identified through the accumulated wisdom from these activities and documents of the past two years.

In terms of current HHS oral health literacy activities, Bailey said that in 2004, seven research projects on oral health literacy were funded through NIDCR. These projects received $15.5 million and have been extended to 2013. The research described by Dr. Divaris at this IOM workshop is one of the projects funded through NIDCR. There are six other NIDCR research initiatives that focus on oral health education:

- Examination of oral health literacy in public health practice

- Health literacy and oral health knowledge

- Latinos’ health literacy, social support, and oral health knowledge and behaviors

- Development of an oral health literacy instrument

- Use of videogames to promote oral health knowledge

- Health literacy and oral health status of African refugees

One of the NIDCR research projects is designed to estimate dental literacy among people enrolled in the Women, Infants, and Children’s (WIC’s) Supplemental Food Program. The goal of the project is to reduce dental health disparities by helping pregnant women and their children to better interpret dental health information, navigate the dental health system, understand instructions, and participate in care decisions. As part of this project, multicenter assessments for oral health literacy are being conducted in Atlanta, Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Washington. This project examines the relationship between health literacy, oral health decision making, and oral health status, and determines the extent to which four different measures of health literacy represent unique skills.

Bailey also described research being sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The San Diego Prevention Research Center was funded to sponsor community dialogue sessions on fluoridation. The project tested whether bringing community members together and giving them both negative and positive messages about fluoridation would allow them to enter into a dialogue and then make evidence-based decisions. Bailey described how this process did not lead to individuals supporting water fluoridation. He said that the study demonstrated that it is difficult to overcome fears when it comes to fluoridation messages. If people are uncertain, then they tend to say no to doing anything.

Bailey described educational initiatives of the Office of Minority Health. This office is creating a cultural competency e-learning continuing

education program for oral health professionals. The Office on Women’s Health is integrating oral health messages into their materials and website. They are also conducting a physician survey to better understand physician’s knowledge and behaviors related to oral health. NIDCR has developed easy-to-read oral health education brochures. They also have a curriculum for first and second graders (Open Wide and Trek Inside), and are developing educational videos. The CDC has tested messages and developed the Brush Up on Healthy Teeth campaign. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is collaborating with text4Baby to include oral health messages. Bailey added that they are also going to award a contract summer 2012 on the National Children’s Health Coverage Campaign.

Bailey provided a list of resources and associated website links pertaining to HHS resources:

• Health Literacy Plans

o CDC Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy

o AHRQ Health Literacy Action Plan

• Training and Education

o Clear Communication: NIH Health Literacy Initiative (http://www.nih.gov/clearcommunication/healthliteracy.htm)

o CDC Health Literacy Portal (http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy)

o HRSA Training for Health Care Professionals (http://www.hrsa.gov/publichealth/healthliteracy/index.html)

• Resources

o IHS Health Literacy Tools and Resources (http://www.ihs.gov/healthcommunications/index.cfm?module=dsp_hc_health_literacy)

o CMS Health Literacy Toolkit (http://www.cms.gov/WrittenMaterialsToolkit)

Bailey concluded by stating that action steps have been identified to advance oral health literacy. These steps are as follows:

• Assure a more competent workforce.

o Train clinicians in communication skills/cultural competency.

o Have staff complete CDC/HRSA courses in health literacy.

• Use plain language in publications and websites.

o Oral health care prevention and education, special populations, access to care, coverage.

• Assist patients with disease self-management.

• Assess and improve user friendliness of our clinics.

• Utilize guidance, resources, and tools.

o Action steps are outlined and resources available for health professionals to make health information and services accurate, accessible, and actionable.

• Foster and enhance collaboration (internal and external).

Kathy O’Loughlin, D.M.D., M.P.H. American Dental Association

O’Loughlin prefaced her remarks by noting the difficulty of changing health beliefs and behaviors and the need to instigate these changes both from the bottom up with patients and top-down with practitioners. Dental care providers can be influenced through educational institutions and dental care delivery systems. O’Loughlin mentioned her 12-year involvement in oral health literacy and the challenges of the field. She said she is optimistic and that progress has been made in oral health literacy. For example, a definition of health literacy in dentistry (Box 7-1) and a framework for understanding it (Figure 3-1) have been accepted by health and dental professionals.

As the Executive Director and Chief Operating Officer of the ADA, O’Loughlin described the twofold mission of the ADA. The ADA’s purpose, as outlined in its bylaws, is to enhance the health of the public and promote the profession of dentistry. O’Loughlin stated that this bifurcated mission creates tension within the organization because resources have to be divided between the needs of 157,000 member dentists who actively seek ADA support and a silent majority of the U.S. population.

The ADA has been active in several dental oral health activities:

- Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General (2000)

- Healthy People 2010 and 2020

- National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health (NIDCR, 2003)

- Institute of Medicine reports (IOM, 2011a,b)

- NIDCR Workgroup on Functional Health Literacy

- Presentations at professional association meetings (e.g., National Oral Health Conference, International Association for Dental Research, American Association for Dental Research, American Public Health Association)

- National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy (2010)

The ADA has learned from these initiatives and is now turning to action and evaluation of the impact of those actions, said O’Loughlin.

BOX 7-1

The Definition of Health Literacy in Dentisty

Health literacy in dentistry is “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate oral health decisions.”

SOURCE: Adapted from Ratzan and Parker, 2000.

She noted that health literacy is a pervasive issue that involves many health professions. Dentists, with their oral health expertise, are essential, but she indicated that they are insufficient to “turn the needle” on this issue. According to O’Loughlin, change will only occur by integrating the efforts of physicians, nurses, social workers, educators, and people in the community who have influence, for example, promotores. Promotores are trained lay health workers that provide basic health education in the Hispanic/Latino community. Some promotores receive about 18 months of oral health education and then work as Community Health Coordinators. They educate, navigate, intervene, provide preventive services, and on occasion, triage and reroute emergency cases to ensure that people in at-risk communities receive needed oral health care.

O’Loughlin relayed an anecdote from a pediatric dentist that illustrates the need for oral health education and clear communication. In the course of talking to a mother about proper tooth brushing, someone in her practice handed the parent a little 2-minute egg timer and told her to use it. The timer is intended to be used as an aid to help children maintain their teeth brushing for 2 minutes. Instead, the mother took the timer home, broke it open, and used the granules to brush her child’s teeth.

The ADA sells millions of dollars of patient education information. It would be very helpful, O’Loughlin said, to have those materials reviewed and appraised in terms of its integrity and level of health literacy.

The ADA is working with the National Advisory Committee to develop a health literacy plan. There are five areas of focus:

- Education and training (change perceptions of oral health)

- Advocacy (overcome barriers by replicating effective programs)

- Research (build the science base and accelerate science transfer)

- Dental practice (workforce diversity, capacity, and flexibility)

- Build and maintain coalitions (increase collaborations)

The ADA is actively working on at least three of these five areas with a focus on three strategic goals. The first goal is to help ADA members succeed (as defined by the members). The second goal is to ensure that the public has access to information so that individuals can be better stewards of their own health. The third goal is to improve the public’s health through collaboration. O’Loughlin described two major collaborations, one a Web-based initiative (Sharecare) and the other an advertising campaign conducted in collaboration with the Ad Council that focuses on oral health.

Two years ago, the ADA joined forces with Sharecare, an online resource launched by Dr. Oz and Jeff Arnold of WebMD that focuses on diet, wellness, and nutrition. Oral health is 1 of 48 topics covered on the site. Questions posted by the public are answered by health professionals. O’Loughlin said that Sharecare is accessed by 2.6 million visitors, on average, every month; growing by 125 percent per quarter in terms of people visiting the site; being used fairly extensively—on average visitors to the site view 10 pages of information; and subscribed to by 1.3 million registered users, people who provide personal information so that they can receive emails, social media, and text messages from this site.

When a Sharecare user types in a question, the site’s search engine finds answers to the question from multiple sources, sometimes competing sources. The site initially had only one dental expert, Bill DeVizio from Colgate-Palmolive; however, the ADA is now actively involved with Sharecare. ADA staff and its nine trained member spokespersons respond to questions that come through the website. Nearly 300 ADA active, licensed, member dentists have answered questions as individual oral health experts on the site (i.e., they do not represent ADA when they answer questions). ADA spokespeople and member dentists have answered more than 3,000 dental-related questions. All dentists can now contribute to the site. The site is monitored for accuracy and if a dentist posts information that is questionable, the dentist is contacted to correct the information. O’Loughlin indicated that the Sharecare initiative has been a great success. She stated that ADA is a fairly trusted source of oral health information and that the ADA’s reviews and policies are evidence-based. In O’Loughlin’s view, this website is a wonderful asset for the public. It allows individuals to ask questions and get credible, trusted answers. The service also helps the ADA by promoting the ADA; reinforcing the ADA’s role as the leading advocate for oral health; engaging the public; and enhancing the recognition and importance of the dentist as the authority on oral health and care.

O’Loughlin believes that the ADA collaboration with Sharecare has helped improve public oral health literacy. When questions are answered

by dentists with credible oral health information, people learn more about their oral health.

O’Loughlin described another recent collaborative effort, a National Roundtable for Dental Collaboration, which is an annual 1-day meeting of dental organizations. In setting the agenda for the first meeting in 2010, representatives of the organizations were asked to prioritize their most important issues and their proposed solutions. The meeting was focused on developing an action plan based on this input. The number one issue submitted by the organizations was health literacy, especially among high-risk populations. The 16 organizations represented diverse interests including those of nine dental specialties, the Dental Trade Alliance (the group representing large manufacturers and distributors of dental products), Medicaid dentists, community health center dentists, public health dentists, and state and territorial dental directors. The meeting led to the formation of a coalition whose principle purpose was to increase the awareness of the importance of oral health among both deliverers and receivers of care. This collaboration led directly to the formation of a new coalition: the Partnership for Healthy Mouths, Healthy Lives. O’Loughlin said that the coalition has grown to include 34 oral health organizations.

The Partnership for Healthy Mouths, Healthy Lives submitted a successful proposal to the Ad Council in 2011. The Ad Council was founded in 1942 to sell war bonds in World War II. It has been responsible for some high-profile public service campaigns, including the Smokey the Bear campaign (relating to fire prevention), and the Crash Dummies campaign (relating to auto safety). The Ad Council specializes in major, multiyear campaigns that leverage an organization’s direct cost contribution to create a $100 million dollar campaign that reaches millions.

The Ad Council will launch a 3-year national advertising campaign in the summer 2012, worth $100 million.1 The goal of the campaign, called “Two Plus Two,” is to reduce the risk of oral diseases in children through prevention. The slogan refers to getting children, by age 2, to brush their teeth for 2 minutes. Campaign messages will target parents and caregivers to raise awareness and change behaviors. The campaign will include a special focus on the Hispanic community and high-risk communities.

Through its media research, the ADA found that people in the United States are more likely to have cell phones than either computers or televisions. Therefore, an ADA-sponsored consumer website, MouthHealthy.org, will be available June 2012. The website will allow people who have

_____________________

1Information on the Ad Council children’s oral health campaign can be found at http://www.adcouncil.org/News-Events/Press-Releases/Coalition-of-More-Than-35-Leading-Dental-Organizations-Joins-Ad-Council-to-Launch-First-Campaign-on-Children-s-Oral-Health (accessed October 1, 2012).

been alerted to oral health issues through the Ad Council campaign to find additional information online. The website, called “Mouth Healthy for Life,” has been designed to be consumer friendly and provide information at different life stages, including pregnancy. The site will also include a dental symptom checklist and information about nutrition.

O’Loughlin concluded her remarks by reiterating that the dental community alone is insufficient to solve the problem of poor oral health literacy. She stated that the ADA has developed good relationships with several physician groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the American Academy of Family Physicians. The ADA has also reached out to representatives of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: for example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). O’Loughlin, stated that the ADA looks forward to future collaborations. She stated that coalitions of partners are able to bring messages related to oral health and prevention to larger audiences.

AETNA: ACTIVITIES IN ORAL HEALTH LITERACY

Mary Lee Conicella, D.M.D., F.A.G.D. Aetna

Conicella is the dental representative to a health literacy workgroup at Aetna. The workgroup includes members from various departments, including medical, pharmacy, behavioral health, and communications. The workgroup has three subgroups to address its primary audiences: members, health care professionals, and employees. The goals of the workgroups are to

- research the effects of health literacy,

- increase awareness,

- provide tools and resources to address challenges, and

- promote plain language.

Aetna assists its members through the use of plain language. Plain language is a way of writing and speaking that helps people understand something the first time they read or hear it. By using plain language, members can find what they need; understand what they find; and use what they find to meet their needs. Conicella said that the use of plain language helps Aetna’s members use services appropriately, better understand health care information, and act on that information. The Aetna employee newsletter includes a column “In Plain Language,” a how-to

guide to simplify speech and prose. This column helps employees find better ways to convey information.

Conicella said it is important that employees embrace the concept of health literacy because it is employees who weave the concepts of health literacy and plain language into the fabric of the organization. Two features of Aetna’s employee intranet address health literacy: (1) Jargon Alerts; and (2) Because You Asked. Jargon Alerts is a once-a-week feature that that focuses on a word that is used, but lacks a clear meaning. Recent examples of words featured include noncompliant, adjudicate, and impactful. These words are used within the industry, but may be confusing to members of the public. The “Because You Asked” feature on the intranet allows employees to submit questions and receive answers about the use of words. A recent example of a question submitted related to the correct use of “flush out” and “flesh out.”

Aetna encourages employees to nominate peers for the Aetna Way Excellence Awards for their work in language simplification and health literacy, said Conicella. In addition, she said that each month a health literacy champion is recognized for creating member materials or otherwise promoting health literacy.

Conicella said that Aetna has had a long-standing commitment to voluntary activities. Every February, during children’s dental health month, dental hygienists, dentists, and other employees visit preschools, schools, and other organizations to educate children about oral health. The Aetna team provided education and screening at the Pittsburgh children’s museum during that time. Oral health education was provided jointly to parents and children.

As part of its outreach to clinicians, Aetna communicates with doctors and other health care professionals about their role in helping patients better understand their health and health care. These clinician awareness activities, include the following:

- Health literacy messaging via ePocrates2

- Health literacy features in the physician newsletter

- A health literacy reference tool on the provider education website

- A cultural competency course for clinicians

- An online continuing education course for dentists

In terms of research and collaboration, Conicella described two research studies that Aetna was involved in, one on asthma health literacy and one on migraine health literacy. Aetna has collaborated with a

_____________________

2ePocrates is a company that creates point-of-care digital products (online and for mobile devices) for health care professionals (http://www.epocrates.com/who).

number of organizations, for example, the American College of Physicians Foundation, the Institute of Medicine’s Roundtable on Health Literacy, the America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) Health Literacy Taskforce, and the American Medical Association Foundation. The collaboration with AHIP resulted in a continuing medical education (CME) course on health literacy for clinicians.

Conicella described a writer certification training program at Aetna which aims to ensure that Aetna communicators

- inform, educate, and engage members/consumers,

- follow Aetna writing guidelines,

- write in plain language,

- simplify codes for explanation of benefits statements, and

- simplify member letters.

Conicella recommended Navigating Your Health Benefits for Dummies(Cutler and Baker, 2006), a book that breaks down the complex health benefits system into easily digestible pieces and helps consumers navigate their way the system.

Conicella described an oral health literacy continuing education course that was designed with Aetna’s research partner, the Columbia University College of Dental Medicine. The course is called Oral Health Literacy: A Dental Practice Priority. The course became available on Aetna’s website in 2009. Aetna’s participating dentists are encouraged to take the course. The course is lengthy and includes a description of the various tools available to assess patient health literacy. For example, the following screening tests are available online to assess patient reading levels:

- Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised (WRAT-R)

- Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM)

- Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA)

- Newest Vital Sign (NVS)

Newest Vital Sign interprets a patient’s ability to understand a nutritional label from ice cream. Conicella pointed out that a dentist does not have to use any of these formal tools and most dentists would not be comfortable with these tools. However, she said that a dentist could add a few simple questions to the health history form that could help them assess the health literacy of their patients (Box 7-2).

The Aetna continuing education course provides a summary of existing dental educational materials and the readability of those resources. The review includes patient educational brochures and pamphlets currently available from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial

BOX 7-2

Examples of Health Literacy Questions

1. How often are medical forms difficult to understand and fill out?

- Always

- Often

- Sometimes

- Occasionally

- Never

2. How often do you have difficulty understanding written information your health care provider (like a dentist or dental hygienist) gives you?

- Always

- Often

- Sometimes

- Occasionally

- Never

3. How often do you have problems learning about your dental or medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information?

- Always

- Often

- Sometimes

- Occasionally

- Never

SOURCE: Chew et al., 2004. From Conicella Presentation, March 29, 2012.

Research and the National Institutes of Health. The reading level of the materials ranges from 4th to 10th grade. When dental terms such as “gingivitis” and “periodontal disease” were replaced with the word “dog,” the reading level of the brochures and pamphlets was lowered, but many of them remained above a 7th-grade level. Conicella stated the many of the materials in use are highly technical. Ideally, materials at the 4th- or 5th-grade reading level are needed so that the majority of people can understand them.

Conicella said that the Plain Language Thesaurus for Health Communication (HHS, 2007) is a useful resource. She agreed with a quote from the thesaurus that relates to patient communication: “It is more important to be understood than to be medically precise.”

To encourage patients to feel comfortable and ask questions, Conicella recommended adoption of the “Ask Me 3TM” method from the Partner-

ship for Clear Health Communication, National Patient Safety Foundation. According to this method, dentists should encourage their patients to ask (www.npsf.org/askme3)

- What is my main problem?

- What do I need to do?

- Why is it important for me to do this?

Conicella described an award-winning, consumer-oriented, Aetna-sponsored website, Simple Steps To Better Dental Health® (http://www.simplestepsdental.com). The content on this website is primarily provided by the Columbia University College of Dental Medicine. The content is comprehensive, however, the reading level was set so that most members of the public could learn from it. The website includes an interactive tool for parents and caregivers of small children to teach them about preventing early childhood caries. Another interactive tool helps assess the risk for caries for adults and children. The website also includes information on oral health and diabetes.

Conicella said that Aetna also works to advance health literacy through collaborations between dentists and physicians. For example, Aetna sponsored three symposia in the past 4 years at the New York Academy of Sciences that brought the dental and medical community together. The symposia focused on the implications of oral health to the aging population, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and pregnancy. Aetna has also been involved with other health conferences, mostly in affiliation with the National Dental Association and their local chapters where there is a good working relationship with the National Medical Association. Three additional collaborative conferences are scheduled for 2012.

DENTAQUEST FOUNDATION ORAL HEALTH 2014 INITIATIVE

Ralph Fucillio, M.A. DentaQuest Foundation

Fucillio described the origins of Oral Health 2014, an initiative funded by the DentaQuest Foundation, formerly known as the Oral Health Foundation. The Oral Health Foundation limited its activities to Massachusetts. The DentaQuest Foundation expanded the mission and has a national focus.

Fucillio recounted an experience he had while volunteering in 2009 in Wise County, Virginia, an area without good access to dental care. Dental services offered through charitable organizations such as Remote Area Medical Volunteer Corps and Missions of Mercy are sometimes

offered in such areas. These volunteer-staffed programs are sponsored by dental societies and other stakeholders and treat people who do not otherwise have access to dental care. Fucillio arrived at the clinic site, a county fairground at 7:00 am. There were already long lines forming for care, with some having arrived days before to be assured of being seen. A circus tent was set up with 90 dental stations. Fucillio observed that while many were being served, the delivery was not the way dental care should be delivered in the United States in a sustainable way. There were many people in pain, with some in severe pain. Most clients were expecting their teeth to be pulled. This experience motivated Fucillio to start thinking about a national movement on oral health. In March 2009, he attended an access to oral health care summit convened by the American Dental Association. The summit involved multiple stakeholders and addressed the long- and short-term needs of U.S. populations that lacked access to oral health care, especially preventive services.

In the three years since the summit, a number of stakeholders have joined together to build a National Oral Health Alliance. A coordination and communication committee worked for 2 years to establish the National Oral Health Alliance. A number of contentious issues, including water fluoridation and workforce issues, had to be discussed among the stakeholders to build new levels of trust, create opportunities for dialogue, ensure civic engagement across sectors, and establish a foundation for a national plan to address oral health. The U.S. National Oral Health Alliance was launched March 22, 2011. Mr. Fucillio recognized two of the other founding board members in attendance, Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Robinson.

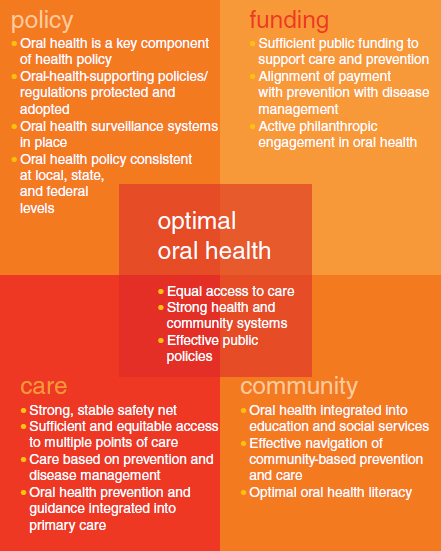

Fucillio identified four system components that are needed for change: funding, policy, community, and care. These four components are interdependent (Figure 7-1). In his view, the overall system cannot change without a change in one of these components. Funding and reimbursement systems may need to change to facilitate prevention-oriented, evidence-based dental care, he said. In the policy arena, Fucillio discussed prevention provisions of the Affordable Care Act that could help people understand both their general and oral health. Social determinants of health fit into community systems and greatly affect health outcomes. Based on his review of the literature, Fucillio estimated that 10 percent of what is spent on health actually improves health and 90 percent of what is going on in people’s lives is what really contributes to whether they are healthy or not. He said that the community is one of the most important places for improvements in health to occur. Using the language of the community is key to health literacy. Fucillio recounted an anecdote from research on language used to describe food. In one study, people from

FIGURE 7-1 Systems change for optimal oral health.

SOURCE: Fucillio, 2012.

southern states were asked if they ate poultry. They reported that they did not. They were more familiar with the term chicken.

DentaQuest Foundation provides funding and engagement opportunities at the state level that address one or more of the six priorities of the National Oral Health Alliance:

- Prevention and public health infrastructure

- Medical dental collaboration

- Strengthening the dental care delivery system

- Data and surveillance

- Financing models

- Oral health literacy

The DentaQuest Foundation offered states $100,000 for the first year of planning. The foundation received 69 letters of intent and 36 proposals. The foundation funded 20 states (Table 7-1). Four of those states are focused on oral health literacy (Arizona, Florida, Maryland, Rhode Island).

Fucillio discussed two colloquia held by the U.S. National Oral Health Alliance. The first colloquium focused on medical and dental collabora-

TABLE 7-1 State Oral Health Programs Funded by the DentaQuest Foundation

| Arizona: American Indian Oral Health Coalition |

• Twenty-two tribes in the state starting regional “roundtables” as a culturally sensitive means of bringing tribes in various regions together |

|

• An “oral health 101” session is hosted by a dental hygienist from the community in which the roundtable is being held |

|

|

• Roundtables work to create consensus around which aspects of the oral health plan are most important to those tribes and how they can work together to implement them |

|

| Florida: Healthy Mouth, Healthy Body Campaign |

• To develop culturally competent messages regarding the importance of good oral health, to create support for public policy solutions and to improve access to dental care |

|

• Develop a series of messages (messaging plan) for their alliance and local coalitions: the plan was officially adopted by their alliance |

|

| Maryland: Maryland Dental Action Coalition |

• Reducing health disparities, enhancing oral health literacy among community-based groups |

|

• Oral health literacy campaign officially launched with engagement by elected officials and the Maryland Oral Health Learning Alliance (created for Oral Health 2014 Initiative) as a support and alignment mechanism to keep the campaign moving forward |

|

| Rhode Island: Rite Smiles-Smart Smiles: Rhode Island’s Oral Health Literacy Improvement Initiative |

• Increase the knowledge and skills of families and providers and improve access to dental care among families and children with Medicaid coverage |

tion. Numerous professions came forward to describe their cooperative initiatives. The second colloquium focused on prevention and public health infrastructure. A third colloquium on oral health literacy was held June 6 and 7, 2012.

Fucillio said that the many oral health literacy initiatives under way point to progress in this relatively new field. He cited as examples of these promising initiatives, the grant programs of Oral Health 2014, coalition development, the National Oral Health Alliance, the Oral Health Coordinating Committee at the federal level, and the current IOM workshop. Fucillio stated that these and other initiatives will contribute to improvements in oral health. However, he cautioned that change will not occur unless literacy levels improve. He indicated that literacy interventions must go beyond targeting individual behavior and reach communities.

Fucillio concluded his remarks by providing four key oral health literacy messages:

- The mouth is part of the body.

- Oral health problems stem from an infectious process in the mouth.

- Dental disease is preventable.

- Oral health literacy and oral health is everybody’s business.

Fucillio encouraged members of the audience to learn more about the Alliance’s national initiatives at the DentaQuest Foundation website (dentaquestfoundation.org).

Roundtable member Kelly began the discussion of the presentations by asking O’Loughlin whether the ADA had reached out to the payor community in terms of involvement with the Ad Council dental health campaign. Kelly suggested that receiving key messages from insurers as well as through the media would reinforce the campaign’s information. O’Loughlin replied that the ADA discussed the Ad Council campaign with representatives of Delta Dental and the National Association of Dental Plans (NADP). The plans have been preoccupied with health care reform legislation. The ADA welcomes collaboration with health and dental insurance plans. She pointed out that the Ad Council “owns” the campaign, has their own website for the campaign, and is in charge of the media launch to the public. All members of the partnering coalition are recognized on the website.

Roundtable member Epstein provided the audience with information about the online Unified Health Communication course offered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The course has

been updated and is now called Effective Health Care Communication Tools for Healthcare Professionals. An hour of ethno-cultural and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT)-specific content is being added to the course and six continuing education (CE) credits can be earned upon its completion. Epstein anticipates the inclusion of additional oral health content in the course so that it will be eligible for CE credits for oral health care providers.

Roundtable member Francis asked Fucillio how social determinants fit into the framework he described that included interconnections between policy, funding, community, and care. Fuccillio replied that social determinants operate on all four components of the framework. Social determinants are usually thought to operate at the community level, for example, by influencing factors affecting people’s everyday lives, such as economics, transportation, education, and housing. However, he said, decisions made in the areas of policy, funding, and care also greatly affect the conditions of people’s lives, which, in turn, affects their health. Fucillio said that a shift of focus from individual behavior to the conditions in which individuals find themselves is an important part of this framework. Francis added that a focus on social determinants is needed because they can preclude access to care. Fucillio agreed and said that if people do not have a place to receive care, or do not have the means to pay for that care, they will likely not get care.

Roundtable member Schyve asked members of the panel to discuss interventions at the level of the individual practitioner that improve communication with patients. He noted that from the practitioner’s point of view, effective interventions such as the teach back method take time. Schyve suggested that taking this extra time with patients would likely mean that fewer patients could be seen in the course of the day. He asked the panel to address this practical issue.

O’Loughlin observed that insurers do not usually provide reimbursement for oral health literacy interventions such as the teach back method. There is a code for the provision of education and guidance, but payors usually do not reimburse for this service. She indicated that fundamental systems issues, including reimbursement, need to be addressed to help practitioners intervene to improve the health literacy of their patients. The first step is to teach dental providers how to intervene in effective ways. O’Loughlin added that there is a Commission on Dental Accreditation communication standard, but that it could be strengthened. She observed that the dental curriculum is already very full. There is a growing recognition that medical and dental schools need to do a better job of teaching practitioners how to communicate effectively, O’Loughlin said. She stated that there is also a greater emphasis on interprofessional collaboration in dental schools and medical schools.

In terms of giving practitioners incentives to use health literacy interventions, Conicella said that dentists who have completed Aetna’s course have not raised this issue. As a practicing dentist, she said that perhaps demands on her time are less than those experienced by physicians. She noted that dentists often use their hygienist and dental assistants to work with them to further health literacy interventions.

Bailey added that informing dentists that health literacy interventions improve outcomes is a powerful incentive. Many dentists do not realize the impact that good communication has on oral health outcomes. He suggested that educating oral health providers about this link would encourage them to incorporate health literacy interventions into their practices.

Roundtable member Patel asked Fucillio whether there is an economic evaluation planned of the state interventions funded through the DentaQuest grant program. She noted that it is useful to have a business case to support public health interventions. Fucillio replied that the state programs have been in operation for a short time (6 months) and that the evaluation process is ongoing. The first year of the grant focuses on planning. Some of the grantees will be selected to implement their plans. The evaluation metrics will vary according to which of the six priority areas the grantees elect to target. One of the financial benefits of the interventions observed so far is that strengthening the oral health safety net has led to improvements in the financial results of the safety net dental clinics. These benefits have occurred in states where there is a primary care association working with the grantee to mobilize local stakeholders.

Ratzan posed a series of questions related to opportunities for sustainable solutions in health literacy. First he asked O’Loughlin how health literacy education can be integrated throughout the health science undergraduate and graduate curriculum. In addition, he noted that revisions to the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) might include health literacy questions. He asked Conicella about incentives that insurers could offer employers to encourage healthy behaviors among employees. Ratzan noted that employers receive a large discount if they can show that their employees are aware of measures such as blood pressure and blood sugar levels. Incentives can be built into the plan structure. Ratzan asked Bailey about the evaluation of the text4Baby program and how it might be tied to the Ad Council media campaign as a resource. He noted that the program has had some impact in terms of improving the rate of flu vaccinations. Ratzan asked more generally, How can we come up with sustainable solutions? He urged the government agencies and other stakeholders to work together.

Fucillio replied that the National Oral Health Alliance was formed to conduct business differently. In his view, the Alliance should be a

public–private partnership. Fucillio added that there are 27 members of the Alliance funders group who are focused solely on oral health. He mentioned that three foundations are sponsoring an interprofessional collaborative on oral health. Fucillio is hopeful that when norms, communication patterns, and the way business is done change, systems will change. Bailey added that one way to “span the silos” is to involve top leadership because they have control across all of the silos. From his perspective Bailey suggested that stating health literacy as a priority across an agency, in his case, the Department of Health and Human Services, is an effective way to motivate integration. He added that agency staff may work within silos, but that this does not preclude having a coordinated effort across silos. Bailey suggested that having a public–private national oral health plan serves to focus on priority areas. Individual agencies can tie into a national strategic framework. He likened this to a zipper that connects all of the partners even though each is working on their own element of the plan.