Human Resources, Competition for Manpower, and the Internationalization of Labor

Moderator:

Irwin Collier

John F. Kennedy Institute

Free University Berlin (FU Berlin)

Mr. Collier introduced the third panel, noting the “smooth transition” from the discussion of the previous session on the globalized market for talent. “Human resources,” he said, “as we have seen, are very much a constraint or an opportunity for innovation policy.” He then introduced the two panelists, Klaus F. Zimmermann of the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) and the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin), and Jan Muehlfeit of Microsoft Corporation.

Dr. Zimmermann said that his current research emphasis on migration and labor markets was “well suited to this important gathering,” and that in the future, human resources “will be even more than in the past the central part of innovation creation, along with the use of new products and services.”

A point he emphasized was that the success of new ideas has to do not only with the “intelligent and market oriented creation of products and services,” but also with the willingness of an educated population to use what is invented. “So I think human capital is in the center of innovative activity. If you talk about innovation policy, you cannot forget education policy, migration policy, and mobility policies. All are issues where we see lots of challenges coming, especially in Europe, which is mobile and has deficits in its education system.”

This was particularly true for Germany, he added. “On the other side of the Atlantic, the United States has at least a legendary tradition in immigration policies that attract the best of the world. But there is the question of what Germany can provide in this debate. I don’t think we should be pessimistic, but we have things to discuss. We have to understand that the future depends on a common effort to face the challenges, especially from the rise of Asia.”

Migration and Innovation

Dr. Zimmermann said that the IZA, based in Bonn, has the largest corps of scientists in economics in the world—about 1,100—who cooperate with researchers in United States and China. He summarized his work at IZA and the University of Bonn from the position that innovation, migration, networks, and mobility go together. More specifically, he said, people with diverse socio-cultural backgrounds may boost the creation of new ideas, knowledge spillovers, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. In other words, innovations are based on knowledge and human capital. Migration may cause innovations, for many reasons, such as destroying and restructuring old ideas and replacing them with new ideas. Also, he said, labor mobility carries knowledge. “Innovation is a product of knowledge and ideas being transmitted between people with different information sets through personal contact.”

He cited several recent IZA Discussion Papers that elaborated on these points. In the first of them “the authors have convincingly found that it’s not the quantity of migration but the diversity of the immigrant population which has stronger effect on patent applications. Also, the average skill of immigrants matters very much. Given that Europe attracts not the skilled migrants of the world, this is very important finding.”16

The second paper Dr. Zimmermann emphasized examined labor mobility and concluded that its effects do not depend on whether people move from outside or inside the country.17 “It’s true that the exchange of people between companies is very important,” he said. “If new people come in, it increases the likelihood of innovation—especially if they come from innovative companies.” This may seem obvious, he suggested, “but it’s also true that if someone leaves a company and goes to another innovative firm, this also has positive effects on the innovative activity of his old company. This means that

_____________________________

16Ceren Ozgen, et al, “Immigration and Innovation in European Regions,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 5676, 2011. Prof. Zimmermann commented: “Distinct composition of immigrants from different backgrounds are a more important driving force for innovation than the sheer size of the immigrant population in a certain locality.”

17Ulrich Kaiser, et al, “Labor Mobility, Social Network Effects, and Innovative Activity,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 5654, 2011. Prof. Zimmermann commented: “Labor mobility between firms is associated with an increase in total innovative activity of both the old and new employer”; “Social network effects are the channel for this mechanism.”

there is interchange that helps improve the information flow between people who have left and those left behind. So there’s an increase in innovative activity for both companies.”

The Human Resource Challenge

Dr. Zimmermann turned to the “human resource challenge,” and the “need for good people.” Demographic trends indicate that there will be an “enormous shortage” of high-skilled workers around the world. This is already apparent today, he said, and will become “more dramatic.” It is not only a problem for Germans and Americans, but also for the Chinese. He added the following details:

• High-skilled workers are the driving force of innovation.

• The competition for high-skilled workers is global.

• High-skilled workers are mostly university graduates.

• Therefore, higher education policies and human capital strategies are crucial.

• A likely scenario is that in 20 to 30 years, the United States will still be the dominant global force for innovation, along with China, while the rest of the world lags.

He noted that the brightest people in the world still want to study in the United States, and to earn a doctoral degree there. “And of course the very best stay in the country. The less well qualified go home and build up a network with the United States.” Europe, on the other hand, “has never wanted to be part of this game, and I think this has to be rethought.” This, he said, requires the reformation of German and European universities.18

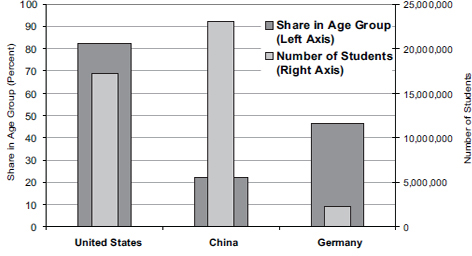

Dr. Zimmermann showed a graph comparing enrollment in higher education in the US, China, and Germany in 2005. It showed that China was already ahead in absolute numbers, but behind both the United States and Germany in enrolled students as a percentage of their age group. He noted that China’s government has “strong ambitions” to increase enrollments.

_____________________________

18He recommended a recent book by Jo Ritzen, A Chance for European Universities: Or: Avoiding the Looming University Crisis in Europe, Amsterdam University Press, February 2011. Ritzen, former rector of Maastricht University, is now a colleague of Dr. Zimmermann at IZA. Previously he served as Minister of Education, Culture, and Science of the Netherlands, as well as vice-president of the World Bank in the Development Economics Department. His book has been published in German as Eine Chance für Europaische Universitaten, by Königshausen & Neumann, June 2011.

China is already ahead in absolute numbers, but there is still substantial scope in relative enrollment rates when compared to the US and Germany

Sources: OECD; Brandenburg and Zhu (2007). Age Group in China: 18 to 22 years; Age group in the US and Germany: 20 to 24 year

FIGURE 01 Enrollment in Higher Education (2005).

SOURCE: Klauss F. Zimmerman, Presentation at the May 25-26, 2011, National Academies Symposium on “Meeting Global Challenges: German-U.S. Innovation Policy.”

European Economists Have Gained in Importance

Dr. Zimmermann then made the “controversial” point that the success of universities depends on the success of university education, which in turn depends on the quality of their research—more than the quality of their students. “Some people do not like that conclusion,” he said, “but that’s how it is and should be. It is good news if we want to attract the best students and generate knowledge and then translate that knowledge into innovation.” He said that when he began his own post-graduate education three decades earlier, Germany was far behind. “Europe was empty. Economics research was dominated by the West. Since then, there has been a big change, and European economists have gained in importance.” As measured by its share of articles in economics journals, Europe between 1991 and 2006 had risen from about a quarter to about a third, while North America’s share shrank from about 2/3 to less than half. Asia’s share doubled, from a low base. “This is likely related to the Bologna process that facilitates the internationalization of research and teaching.” He said

that except for the 10 best universities in the West, European researchers publish more papers per university.19 In addition, he said there was a three-fold increased in the number of publications by German economic research institutes in SSCI-listed journals between 2000/01 and 2005/06.20 In addition, he said, the number of articles published by DIW Berlin in SSCI-listed journals rose from 59 in 2008 to 78 in 2009; less than 10 were published in 2000.21

In short, he said, the process of catching up is still incomplete, with the per-capita number of publications in economics journals in Germany still substantially lower than in the United States. But the gap has closed since the early 1990s, he said, with international cooperation in Europe and across the Atlantic identified as an important factor.22

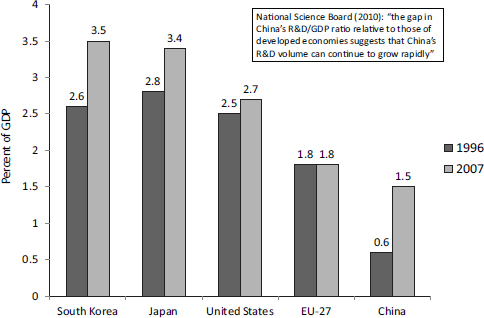

China’s Push for Strength in S&E

Dr. Zimmermann widened his comparison to include a broader picture of science and engineering. Between 1988 and 2008, the number of S&E journal articles by European authors had risen from 146 to 233, while the number by U.S. authors rose less, from 170 to 199. The increase in Asia was far more dramatic, however, rising by a factor of 12, from five to 61, primarily because of the increase from China.23

China is pushing hard to increase its strengths in science and engineering, he said, including remarkable programs to invest money and apply development strategies to recruit the best people. “I have met with people who are organizing this for China,” he said, “and they have a very public plan to be the world’s scientific leaders by the year 2050.” Among the milestones since the opening reforms of 1978, he said, were the following:

• Dramatic increase in the number of students enrolled in Chinese higher educational institutions (reaching 20 million in 2008).

• An increasing trend of Chinese students studying abroad (1.4 million in 2008).

• Tremendous scholarly output by China, with clear priority in natural sciences (59 percent of the articles overall).

_____________________________

19The Economist, February 17, 2011.

20Rolf Ketzler and Klaus F. Zimmermann, “Publications: German Economic Research Institutes on Track,” Scientometrics, 80(1):233-254, 2009.

21Annual reports of German economic research institutes, Zimmermann calculations.

22Ana Rute Cardoso, Paulo Guimaraes, and Klaus Zimmermann, “Trends in Economic Research: An International Perspective,” Kyklos, 63(4):479-494, 2010.

23National Science Board, Science and Engineering Indicators 2010, Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, 2010; Amelie F. Constant, Bienvenue N. Tien, Klaus F. Zimmermann, and Jingzhou Meng, “China’s Latent Human Capital Investment: Achieving Milestones and Competing for the Top,” IZA Discussion Paper 5650, 2011.

• More International students studying in China (almost 200,000 in 2007).

Source: Constant, Tien, Zimmerman, and Meng (2011, IZA DP 5650);

Based on National Science Foundation: Science and Engineering Indicators 2010

FIGURE 2 China on the fast track…and there still is scope for improvement.

SOURCE: Klauss F. Zimmerman, Presentation at the May 25-26, 2011, National Academies Symposium on “Meeting Global Challenges: German-U.S. Innovation Policy.”

Dr. Zimmermann concluded by emphasizing the importance of the “global tug-of-war” for talent, and reiterated that “whoever wins the battle will be the victor in the 21st century.” He closed by reporting part of a conversation between Richard Freeman, a noted labor economist at Harvard, and a Harvard physicist who works closely with overseas scientists and engineers. Prof. Freeman said to the physicist, “Ah, so you are helping them catch up with us?” The physicist answered, “No, they are helping us keep ahead of them!”

A MICROSOFT PERSPECTIVE ON THE UNITED STATES AND EUROPE

Jan Muehlfeit

Chairman Europe

Microsoft Corporation

Dr. Muehlfeit introduced himself as a software engineer by profession, but “always interested in the relationship between technology and human beings.” When he was born, he said, the price of a transistor was one dollar; today a dollar will buy one billion transistors. “This is driven by Moore’s Law,” he said, “and that will influence everything for the next 10 to 15 years.” He said that the CEO of Daimler Benz had told him there are 19 “full-fledged computers” in a new car, and that Daimler’s budget for software was 60 percent of its total budget. “Cars are in fact software products,” he said. “If you look at all the skills around the industry, whether for a software engineer, a designer at the top of the pyramid, or a services man at the bottom of the pyramid, the skill set of everybody will move up because of the technology.”

The New Era of Cloud Computing

Another big change would be the advent of cloud computing, he said, which would play as large a role in the knowledge era as electricity played in the industrial era. “What cloud computing means is that ICT will be delivered as a utility. That will bring huge cost savings, productivity, and innovation.” Today, Dr. Muehlfeit said, a typical state organization may have to allocate 90 percent of its ICT budget to maintenance costs, leaving little for innovation. “Once you deliver software services through the Internet as a utility, you move your spending model from capex to opex, and that will change everything.”

The “cost savings, productivity, and innovation” of the cloud were critical for Europe, he continued, because of three challenges shared with the United States. The first is debt; the second is demography, with both regions having to confront an aging population; and the third is the need to raise GNP growth. “We need to run faster today than we ran yesterday, but we also need to run faster than the others. While in Europe run fast in some ways, we lag behind in growth.”

Another challenge, Dr. Muehlfeit said, is to revitalize education. Technology itself would not be a sufficient advantage, because it spreads so quickly around the world that it becomes a commodity. “We will mainly compete as human beings and organizations,” he said, “but also as countries through our ability to unlock human potential.” This can be done only by “improving education at one end and lifelong learning at the other. We need to introduce a startup mentality.” He reviewed the case of Korea and Ghana. In 1950, the GDP per capita was about the same in both countries, whereas today Korea has soared far ahead. “It’s very different because in Korea, education

became the mantra for the country. “Would you buy a Korean TV 15 years ago?” he asked. “Probably not. Today I buy a Samsung instead of a Sony. That’s what education can do.”

Today, he said, education in the EU and the United States were lagging. “There is an old saying: if you tell them, they will forget; if you show them, they will remember; if you involve them, they will understand. We need to change education in that way.” He said that he chaired the European section of the World Economic Forum on Education, and was very interested in the results of PISA, which measures 15- and 16-year-old students’ skills in mathematics, science, and reading. “The results show you pretty much what you will get in the economy and innovation 7 to 10 years later,” he said. New champions were emerging. Usually PISA is won by the Finns, he said, because their educational system is so good, or by the Koreans. Last year, however, “students from Shanghai beat both groups by thirty points in every category. That is equivalent to about one year’s advantage in reading, mathematics and science.”

Not only STEM skills, but also ‘Soft’ Skills

The development of new skills in mathematics, science, and logic would be needed to drive an innovation economy, but not sufficient. The best computers today are beating the best chess players. “That’s why I say we need STEM-plus—STEM plus soft skills, self-awareness, creativity, innovation.” He returned to the example of Finland, which established two years ago an “Auto University,” or Innovation University, where students study not only technology and economics, but also art. “This is a broad concept, and they’ve got excellent results. They are trying to recreate a startup mentality.”

Dr. Muehlfeit concluded by underlining the need for better life-long learning programs. He described some joint research between Microsoft and the International Data Corporation; one conclusion was that in five years, 90 percent of all jobs will require at least basic electronic skills. Today, he said, 40 percent of the European population still lacks e-skills. “We need to continue lifelong learning. I’ll illustrate what is wrong. When kids are in kindergarten in Europe, 90 percent of them would like to be innovators and entrepreneurs, would like to do something out of the comfort zone. By the time they leave university, only 17 percent feel that way, and only 4 percent will actually do it. That’s because the old system, which is based on logic and memorizing, is not unlocking human potential.

“Imagine a system where through technology you will be able to learn in your own individual style. Today the base of the educational system is grounded in the industrial era, when we decided the factory is a good model for education. The factory is a place where everyone is told what to do.”

Dr. Muehlfeit ended by challenging his audience to unlock the creativity and innovation of students and adults alike. “Now we know that everybody learns in their own way, and that’s what technology through e-learning can deliver. Research by Gallup says that 80 percent of all job holders

are just doing their work for the money—not because they like it. Imagine being able to unlock those human talents and strengths. In my view that’s what we need to do. In Europe we spend a lot of time discussing universities, but I think we need to reform the whole educational outlook, beginning with primary and secondary grades, in the same way.”

Dr. Wessner asked whether the panelists through that Germany would succeed in attracting more students and professors from abroad.

Dr. Muehlfeit agreed that Germany should think harder about “smart” immigration to attract European professors back. He cited Canada, where more than 40 percent of people have a university degree, as an example of a country doing an excellent job of smart immigration, and rising higher in innovation indexes. In EU universities, he said, only 2.6 percent of students were non-European students. “The mix of cultures and the drive for innovation are missing here—while more than 50 percent of students in the United States are non-Europeans.” Another data point he offered was that 80 percent of all software startups in Silicon Valley during the last 10 years were led by first- or second-generation Chinese or Indians.

Dr. Zimmermann returned to the topic of immigration policies, saying that in principal, anyone in the world with a university degree and a job offer could come to Germany to work. But he acknowledged that this situation might not be widely known, or believed. Whatever the reason, he said, “nobody is doing it; a few hundred are coming worldwide. So Germany has the standing of a fortress, a country that does not want to attract high-skilled labor.” Only people with lower skills come for work. To attract the others, he said, a perceptual problem must be overcome. “Really, there’s nothing to fear from high-skilled migrants, because they only increase efficiency and create innovations; they are also good for equality. It’s proven that the more high-skilled people come into the country, the more equal the society will become.” As a useful goal, he advocated a special passport for high-skilled migrants, and welcoming them. “We should leave it to the people themselves to decide where to work, and not to governments.”

Dr. Collier, the moderator, noted that competition for skill scientists, innovators, and educators might look very different in coming years. At the beginning of the 20th century, he pointed out, when someone said typewriter, they were probably talking about a job description—a human who typed. Irving Fisher, at beginning of his book, On the Making of Index Numbers, thanked his computer, and then named the man who was his computer. “Educator and innovator still have human faces,” he said, “but as we heard in the case of e-learning, ‘educator’ might soon become an electronic machine. Perhaps the innovator will still have a human face.”