![]()

This chapter examines the effects of deployments to Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) on the mental, emotional, and social well-being of military family members, including spouses, children, and caregivers. It also discusses issues related to the availability of programs and services for military families. Military family members are an important part of the readiness and well-being of the military force. The care and support of military families is considered a top national security policy priority in recognition of the integral role family members have in supporting service members and, therefore, the mission of the military. With that priority, various challenges arise. Throughout this chapter, the committee presents evidence that military family members have to deal with additional relationship problems, impairments in psychologic and physical well-being, responsibilities as caregivers of children or wounded service members, and overwhelming household duties. The committee’s primary focus is on the impacts of deployment on military families, and not on the entire scope of experiences faced by military families. Given the exceptional demands that deployments to OEF and OIF have placed on military families and the impact that family concerns have on soldiers’ well-being, there continues to be a need for military leaders to gain a better understanding of the needs of families and to use that understanding to implement more-effective coordinated programs and services for the good of military families and, thus, for the military as a whole.

CHARACTERISTICS OF MILITARY FAMILIES

Military families are more diverse than most statistics or research might suggest. Many families do not meet the criteria used for official counts of military families and, therefore, are not included in the data (for example, common-law spouses). Because of that, this chapter reports information only about a subset of military families: those of service members in heterosexual marriages and parents with dependent children who live with them at least part of the time. The committee views the military’s definition of family as narrow and out of step with the diversity in family arrangements in modern society. The committee found little or no information about parents or siblings of service members (who are sometimes relied upon for important caregiving responsibilities), unmarried partners, stepfamilies, children who are not legal dependents (for example, stepchildren or nonresidential children), gay families, service members acting as substitute parents, or other nontraditional family configurations. Most published studies focus on active-duty male military personnel married to civilian wives.

Because women constitute a relatively small number of service members, they are sometimes excluded from studies. As the number of women in the military continues to increase, it becomes even more important that they be included in research studies.

Despite the apparent popularity of marriage among military members, nonmarital intimate relationships are likely to become a more prominent feature of the relationships of service members in the future, as they are in the population as a whole, and methods of counting relationships may need to be amended as a result. The general population has been characterized in recent decades by rising tendencies for individuals to delay marriage and to cohabit before marriage (Copen et al., 2012). Delays in and alternatives to marriage might become more evident in the military, especially as policies change in the aftermath of discontinuing the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy (McKean et al., 2011). Thus, marital status might become an increasingly inaccurate index of relationship patterns, and useful information about the health of intimate relationships of military members might be overlooked if tabulation methods are not adjusted.

Defining Military Families

Multiple definitions of family are used in the Department of Defense (DOD), each tied to specific regulatory requirements. The most common definition uses eligibility for military identification cards, which are necessary for access to health care, military exchanges, and a variety of supportive services for families. Military identification cards are currently issued to spouses and unmarried children of service members—exceptions and additional categories are defined by children’s ages, student status, or special needs and by whether the marriage ends in divorce or in death of the service member while on active duty. Spouses and unmarried children of reserve-component members are covered while the service member is on active duty for more than 30 consecutive days (DOD, 2012d). Stepchildren may or may not qualify for military identification cards, depending on such factors as age, student status, and the circumstances of the biologic parents.

Single service members are not irrelevant in a chapter focused on the implications of deployment for family life. Single service members might have completed or be in the process of establishing families; for example, they might have cohabiting partners or they might be in close relationships that are precursors to marriage. The population of single service members also includes previously married individuals who might be in the process of establishing a second family. All service members, especially those who do not have spouses or partners, might rely on parents, siblings, or other family members for substantial emotional or tangible support, especially if they encounter hardships, such as illness, wounds, or other major life challenges. However, little research has examined family issues as they relate to single service members.

Demographic Characteristics of Military Families

This section describes the demographic characteristics of families of active-duty forces and selected reserve components. Because data presented here are derived from the DOD’s annual demographic profiles of the military community (DOD, 2011b, 2012a) and represent all service members—not only those who have been deployed—they will not be identical to the data presented in Chapter 3, which include only service members who have been deployed.

TABLE 6.1 Summary of Selected Demographic Characteristics for DOD Active-Duty and Selected Reserve Members

| Status | Percent of Active-Duty Membersa | Percent of Selected Reserve and National Guard Membersb |

| Percent married (enlisted, officers); (male, female) | 56.6 (54.0, 69.6); (58.5, 45.7) |

47.7 (43.7, 70.6); (50.1, 37.0) |

| Percent in dual-military marriages (sex of active-duty member: male, female) | 6.5c (3.9, 21.6) | 2.6d (1.3, 8.6) |

| Percent of married members in dual-military marriage (sex of active-duty member: male, female) | 11.5 (6.8, 47.3) | 5.5 (2.6, 23.3) |

aIncludes 1,411,425 members of the four DOD active-duty branches (Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force). Limited data are included for the active-duty Coast Guard (Department of Homeland Security).

bIncludes 855,867 members of the six reserve components (Army National Guard, Army Reserve, Navy Reserve, Marine Corps Reserve, Air National Guard, and Air Force Reserve) and the Coast Guard Reserve.

cOf these, 81.8% are enlisted members, and 18.2% are officers.

dOf these, 76.1% are enlisted members, and 23.9% are officers.

NOTE: Data are derived from a variety of sources, including the Active Duty Military Personnel Master File, the Active Duty Military Family File, the Reserve Components Common Personnel Data System, the Reserve Components Family File, and the Defense Enrollment and Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS).

SOURCE: DOD, 2012a.

Marital Status of Active-Duty and Selected Reserve Members

Marriage Patterns

Over two-thirds of active-duty and reserve officers are married, as are over half of enlisted active-duty service members and nearly half of those in the selected reserves (see Table 6.1). Reflecting the general makeup of the services, the great majority of both active-duty military (93.1%), and selected reserve (88.1%) spouses are female (DOD, 2011b). Male military members ages 18 to 41 are significantly more likely to have married at some point in their lives than are comparable civilians, particularly if they are black, Hispanic, or hold enlisted rank (Karney et al., 2012). On the basis of 1999 data from the Active Duty Survey of Military Personnel, Lundquist (2004) found that black service members in their early 20s were at least three times more likely to marry than their civilian counterparts and that the large marriage gap present between black and white civilians did not exist for those in the military.

Although less is known about the marital patterns of women serving in the military, they are less likely to be married than their male counterparts, a pattern not observed among civilians of similar age. Women in the military are also much more likely to be married to other service members: In 2011, female active-duty service members and women serving in the reserve component were more likely than their male counterparts to be married to a fellow service member. Nearly half of married women on active duty were married to another service member (DOD, 2012a).

In summary, military members are as likely or more likely to be married than their civilian counterparts, and this factor is particularly true for officers and members serving on active duty. Although the prevalence of marriage has been declining steadily in the civilian

population, in the military it has been essentially level, having some fluctuations, over the past two decades.

Divorce Patterns

An estimated 4.1% of married enlisted members and 2.1% of married officers divorced between September 2010 and September 2011. This percentage is a substantial increase over 2000 rates, when an estimated 1.4% of married officers and 2.9% of married enlisted members had divorced during the previous year. This increase was especially steep for married enlisted soldiers (2.3% in 2000 compared with 4.0% in 2011, a 74% increase) and sailors (2.6% in 2000 compared with 4.6% in 2010, a 77% increase).

Among the selected reserve, an estimated 2.8% of married enlisted members and 1.9% of married officers divorced during the 1-year period before September 2010. This percentage shows modest increases above the 2000 rates, which were 2.4% for married enlisted members and 1.6% for married officers.

Data analyses by Karney et al. (2012), however, suggest that the apparent increase in divorce rates in military relative to civilian populations is not statistically significant and does not reflect a widening gap between civilians and military members, at least during the 4 years before and after the start of combat operations in Afghanistan in 2001. In fact, male military officers and enlisted members reported being currently divorced at either the same or lower rates than civilian men with comparable education, age, race or ethnicity, and employment status both before (1998–2001) and during the war (2002–2005) (Karney et al., 2012).

Marriages of women in the military are more likely to fail than those of men (Karney and Crown, 2007; Lundquist, 2006). Karney and Crown (2007) examined military personnel records to track the marital status of service members over a 10-year period (1996 to 2005) and found that rates of marital dissolution for female service members were more than double those of their male counterparts. Regarding marital dissolution and race, Lundquist (2006) found that black service members were 53% less likely to divorce than whites, unlike in the civilian population, in which blacks were 30% more likely to divorce than whites. When only one partner was in the military, white dual-military couples were 40% more likely to divorce than black couples.

In summary, although overall divorce rates in the general population have been falling during the past decade, divorce rates in the military have risen noticeably. Nonetheless, on the basis of comparisons of matched civilian and military men, Karney et al. (2012) concludes that men serving in the military are no more likely than their civilian counterparts to divorce and that this gap did not widen between 1996 and 2004. A subsequent section about deployment and married couples examines research on the impact that deployment has on marital dissolution.

Family Responsibilities of Active-Duty and Selected Reserve Members

Information on the family status of service members is presented in Table 6.2.

TABLE 6.2 Family Status of DOD Active-Duty and Selected Reserve Members

| Status | Percent or Number of DOD Active-Duty Members | Percent or Number of Selected Reserve and National Guard Members |

| Percent with children (overall) | 44.2% | 43.3% |

| Percent married to civilian, with children | 36.1% | 32.5% |

| Percent dual-military with children | 2.8% | 1.5% |

| Percent single with children | 5.3% | 9.4% |

| Average number of children of members with children | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Percent of children ages 0 to 5 | 42.6% | 28.8% |

| Percent married to civilian with no children | 14.0% | 12.7% |

| Percent dual-military with no children | 3.7% | 1.2% |

| Percent single with no children | 38.1% | 42.9% |

| Percent with family responsibilitiesa (enlisted, officers) | 59.0% (56.7%, 70.0%) | 56.4% (52.9%, 76.4%) |

| Average number of dependents of members with dependents | 2.4 | 2.4 |

aMembers are classified as having family responsibilities if they have a dependent (spouse, children, other dependents) registered in the Defense Enrollment and Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS).

NOTE: Children category includes minor dependents age 20 or younger or age 22 and younger enrolled as full-time students.

SOURCE: DOD, 2012a.

Over half of active-duty and selected reserve members have family responsibilities—that is, are married or have children or have another dependent registered in the Defense Enrollment and Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS)—as do over two-thirds of active-duty officers. Among active-duty enlisted service members, Army-enlisted soldiers are more likely to have family responsibilities than enlisted members of other active-duty service branches (63.5% for Army enlisted, compared with 53.0% for Navy, 46.3% for Marines, and 55.7% for Air Force enlisted). Approximately half to two-thirds of enlisted members of the selected reserve across reserve components have family responsibilities, the exception being Marine reserve families, in which just over a quarter (27.1%) have responsibilities. The majority (67.1%) of active-duty single parents are male service members. However, female service members are much more likely than males to be single parents (12.1% vs 4.2%, respectively).

The large minority of minor dependent children of active-duty members are 5 years old or younger (42.6%), followed by 6 to 11 years (30.7%), 12 to 18 years (22.4%), and 19 to 22 years old (4.3%; includes full-time students). The children of selected reserve members tend to be older than those of active-duty members, 28.8% being ages 5 or younger, 29.7% being ages 6 to 11, 29.6% being ages 12 to 18, and 11.8% being ages 19 to 22.

A study examining marital transitions among service members found that almost onethird of service members (30%) had nonresidential children, a strikingly high percentage in a population where 64.8% of the members were younger than age 30 (Adler-Baeder et al., 2006). Almost all of the service members with nonresidential children had only nonresidential children,

meaning that under military rules, they were defined as single, not as single parents. Among remarried respondents, 42.2% had children from a previous relationship.

In 2008, the Military Family Life project included two items related to marital transitions in a survey of a probability sample of 28,500 military spouses. The first item asked respondents, all of whom were married or separated, if they were currently living in a stepfamily; 20% indicated that they were. In addition, 35% of the participants indicated that they had a child from the service member’s or spouse’s prior relationship or were acting as parents for someone else’s child, such as a grandchild, niece, or nephew. Thus, a substantial proportion of service members are living in stepfamilies or are acting as parents for the children of others.

A small proportion of active-duty (0.7%) and selected reserve (0.2%) members are responsible for one or more adult dependents, such as a parent, grandparent, sibling, disabled older child, or other adult claimed as a dependent in the DEERS system. In the large majority of cases, the dependents are females age 51 or older.

DEPLOYMENT AND FAMILIES

Rewards and Challenges of Military Service for Families

Understanding the effects of wartime deployments on military families requires some understanding of the baseline conditions of military life. The demands of military service may characterize other occupations, but rarely with the prevalence and frequency of demands that occur in military life (Castro et al., 2006). However, military service offers tangible and intangible benefits and supports that other occupations might lack.

Rewards of Military Service

Research about military families tends to focus more on negative than beneficial aspects, but the latter are nonetheless important. Rewards of military service can include personal growth from surmounting difficult challenges, increased appreciation of personal relationships, increased earnings from hazardous duty pay, and a sense of purpose from performing an important mission for the country (Newby et al., 2005a).

A review of studies of appraisals by veterans from a variety of combat and peacekeeping operations (Schok et al., 2008) found that most veterans reported positive aspects of their experiences, primarily in three domains: self-image, such as self-discipline, self-confidence, and coping; in social relationships, such as cooperating better and becoming more tolerant; and in personal growth and priorities in life, such as valuing life, recognizing the importance of family, and strengthening of faith. In a focus group, data gathered by Hosek et al. (2006) showed that service members reported similar themes, including satisfaction from using the skills they had acquired in training and fulfillment of a sense of duty.

Family members also reported increased closeness, patriotism, pride, civic responsibility, and personal growth (Werber et al., 2008). Being in the military can also provide a sense of community for military families and a social support system of other military families who understand the demands of military life. Although relocations can be stressful, military life provides families with the opportunity to see and live in different parts of the country or the world that would not otherwise be available to them.

Challenges of Military Service

Military service includes a number of stressors related to the structure of work (Adams et al., 2006; MacDermid Wadsworth and Southwell, 2011; van Steenbergen et al., 2008). Military work is demanding, often requiring long hours and physically tiring tasks (Huffman and Payne, 2006; Kavanagh, 2005), and even nondeployed units must work to prepare for future deployments and support currently deployed units. Service members may be assigned with little advance notice to a variety of duties that require repeated episodes of time away from their families (for example, temporary duty assignments, training, disaster relief, humanitarian aid, and combat), all of which may expose service members to danger (Kavanagh, 2005).

Service members and their families are required to relocate much more frequently than civilian families (every 2 to 3 years), with little opportunity to influence the choice of the next duty station (DOD, 1998; GAO, 2001). In 2010, 31% of military members (excluding unmarried service members living in barracks) moved, compared with 13% of civilians (US Census Bureau, 2011c). Rates of international relocations, which can be more challenging than domestic moves, are four times higher among military families than their civilian counterparts (Reinkober Drummet et al., 2003). Frequent obligatory moves are associated with frustration and decreased satisfaction with military life (GAO, 2001). Lack of support and isolation in the new community is particularly mentioned as a concern by spouses (Burrell et al., 2006). In addition to their emotional consequences, frequent relocations disrupt the ability of spouses to achieve educational or career goals (Burrell et al., 2006; Eby et al., 1997; Harrell et al., 2004). Relocations can require spouses to transfer certifications and change jobs or retrain. Military spouses are less likely than their civilian counterparts to work full-time, to average fewer work hours and fewer days in the year, and to earn less than spouses of civilians (Hosek et al., 2002; Lim and Schulker, 2010).

Beyond dealing with the occupational demands of the service members, military life also may impose codes of conduct for family members as well as service members, especially when living in military housing, using military support services, or when the service member occupies a leadership position (Segal, 1986). Military scrutiny and expectations for good conduct on and off duty may lead service members and their families to perceive a lack of privacy. Furthermore, the behavior of spouses and children can impact service members and their careers. For example, spouses’ problematic behavior (e.g., traffic violations, financial problems, substance abuse) can come to official attention and result in pressure on service members to “control their family member” (Segal, 1986).

The high proportion of military women in dual-service marriages, when combined with the high rates of marital dissolution among military women, raises questions about the severity of the unique challenges faced by dual-military families in coordinating leaves between parents, arranging child care, and other challenges posed by dual commitments to military service (Bethea, 2007). As discussed by Huffman and Payne (2006), individuals in dual-military marriages have multiple roles—at the very least as spouse and as service member, and often as parent or active community member. In dual-military marriages, having multiple roles can have positive implications, but the difficulty of fulfilling obligations associated with each role can strain individuals, particularly for those with children. In addition, military-specific challenges, such as being in the presence of danger, working at a high pace, and frequent or long separations, are magnified in dual-military marriages.

Impact of Deployments on Families

Deployments are not single events but complex configurations of predictable and unpredictable experiences. Deployments are diverse, varying along several dimensions. The most obvious dimension is content, such as exposure to trauma, physical demands, harsh living conditions, access to resources, and the ability to communicate with family. The dimensions of deployment structure include duration and frequency of individual deployments, which also leads to consideration of “dwell time” or the interval between repeated deployments. As deployments accumulate, cumulative duration becomes relevant. Although every deployment comprises a before, during, and after period, there are differences in the amount of advance notice service members receive and when, where, and for how long they must receive training before departing or after they return. Deployments have been categorized as both normative and catastrophic. The former is characterized by adequate time to prepare, by predictable duration and content, and by relatively mild emotional distress; the latter is characterized by little advance warning, uncertainty and danger, and prolonged emotional distress (McCubbin and Figley, 1983; Wiens and Boss, 2006). To the extent that every deployment comprises before, during, and after deployment periods, they have a predictable structure. The duration and content of these phases vary widely, however—raising caution about the confidence with which predictions can be made about the implications for families.

Several scholars have constructed stage models to describe the emotional experiences and coping challenges that are thought to characterize the deployment and reunion periods (Wiens and Boss, 2006); see also Mateczun and Holmes (1996), Peebles-Kleiger and Kleiger (1994), and Pincus et al. (2001) for more information about stage models. Although these stage models are appealing in their clarity and appear to be consistent with the findings of some empirical studies, no longitudinal studies have documented that these stages occur, occur in the proposed sequence, incorporate the proposed experiences or challenges, or display the proposed durations.

Although the number of published peer-reviewed studies of the impact of OEF and OIF deployments is rapidly increasing, large knowledge gaps remain. For example, many studies do not incorporate family factors or gather data from family members. The studies that do incorporate that information focus mostly on spouses and to a lesser extent on children. Little attention is given to the parents or the “significant others” of service members, a particularly concerning gap for single service members. Similar to studies of military families in general, most OEF and OIF studies focus on male military personnel married to civilian women and serving in the Army (Kelley et al., 2002). Many studies focus on negative consequences, especially posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), rather than other potential sequelae of deployment.

Almost no studies have been conducted that include prospective data from the predeployment period. A few have gathered data during deployment but rarely from service members and even more rarely from both service members and family members. Most research—even of the period during deployment—has been conducted following return from deployment, and most studies are cross-sectional rather than longitudinal (de Burgh et al., 2011). Two large longitudinal studies, currently in the data-collection phase, are likely to generate important data about the effects of military service and deployments on families in the coming years. The family component of the Millennium Cohort Study is recruiting 10,000 spouses of service members participating in a 20-year prospective study of four cohorts totaling 150,000

service members. Data gathered from these spouses will permit comparisons of families of combat-deployed, noncombat-deployed, and nondeployed service members (Crum-Cianflone et al., 2012). The RAND Corporation is conducting a prospective, longitudinal study of approximately 2,000 military families who are expected to experience a deployment. This study will follow the cohort for 3 years; data will be gathered across a number of domains every 4 months. The design includes measures that will be repeated before, during, and after the deployment phases. One of the primary goals is to understand both risk and protective factors across the deployment phases in an effort to define family readiness. Other key elements of this study include data collection from multiple respondents per family, including one child 11 to 17 years old. Measures include physical health, behavioral health, marital relationship, parenting, use of services, career intentions, and deployment experience (RAND Center for Military Health Policy, 2012).

Theoretical Models

Several theoretical approaches have been presented to account for families’ experiences of deployment. Most of them take a systemic approach, recognizing that families have properties distinct from the characteristics of individual members. Systemic approaches also draw attention to patterns of information flow that can foster or impede adaptation to challenges within families.

The theoretical perspectives used to account for the impact of deployment on families focus on stress processes (see Karney and Crown, 2007; McCubbin, 1979; Patterson, 2002) or on patterns of family resilience (see Saltzman et al., 2011; Walsh, 2006; Wiens and Boss, 2006). Several approaches are based on the attachment theory, which posits that individuals develop internal working models for attachments to others during childhood that condition their responses not only to separations from primary attachment figures but also to interactions with future partners and children. Attachments vary in their characteristics and may be secure or insecure, the latter characterized by anxiety or avoidance. Deployment constitutes a significant challenge to attachment systems and, depending on the nature of attachment relationships among family members, can result in reactions ranging from adaptation that allows the family to function well during separation and incorporate the service member on his or her return and ranging to problematic arrangements that “close ranks” against the service member (Riggs and Riggs, 2011).

Finally, attention is being given to the conditions surrounding military families, including informal support from social networks of family, friends, colleagues, and others, as well as formal support from community agencies and programs. This perspective is prompted in part by greater recognition of the differences between the circumstances of active- and reservecomponent families (Bowen and Martin, 2011; MacLean and Elder, 2007; Wiens and Boss, 2006).

Characteristics of Deployments and Impact on Families

Families appear to experience greater stress and anticipate more difficulties when deployments are longer (Booth et al., 2007; Orthner and Rose, 2002). In a systematic review of studies of deployment length, Buckman et al. (2011) concluded that longer deployments are associated with adverse effects on service members and their families, deployments having a possible threshold of 6 months, beyond which negative effects are more likely to occur.

Several studies suggest that cumulative duration of deployments might be more important than frequency of deployment or the duration of a single deployment for certain family-related outcomes (Chandra et al., 2011; Hurley, 2011). For example, Lara-Cinisomo et al. (2011) found that caregivers who experienced more months of deployment of military members during the past 3 years (but not a larger number of deployments) reported lower relationship satisfaction, more relationship hassles, and poorer emotional well-being. Mansfield et al. (2010) found that the number of cases of depression was larger among wives whose husbands had been deployed longer. Franklin (2011), however, found that reports of psychologic symptoms on the Air Force Community Assessment rose with both frequency and duration of deployment. For length of deployment, but not for frequency, the connection to relationship quality was mediated by psychologic symptoms. These findings probably underestimate the impact of the frequency of deployment because most studies exclude deployments lasting less than 30 days or deployments not in support of war operations. Thus, the number of service members’ departures from and returns home are greatly underestimated, and the statistical effects associated with deployment frequency may be attenuated as a result.

There is considerable evidence that family-related concerns weigh heavily on service members during deployment. In each administration of the Army-led Mental Health Advisory Team (MHAT) surveys, concerns about being separated from family are among the foremost deployment concerns, as reported by about one-third of service members (MHAT-VII, 2011). Responses to the 2008 DOD Survey of Health-Related Behaviors indicated that service members who had been deployed recently were significantly more likely to report high family stress than were service members who had not been deployed; levels of these concerns did not change between 2002 and 2008 (Bray et al., 2010). In another study, British Forces service members surveyed during deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan reported poorer mental health when negative events occurred at home and when they perceived poor military support for their families. These findings were firm regardless of combat exposure but were somewhat weaker in the presence of strong military unit cohesion or military leadership (Mulligan et al., 2012). Skopp et al. (2011), in a large study that included pre- and postdeployment data from 2,583 Army soldiers, found that female soldiers with higher levels of combat exposure were significantly more likely to screen positive for PTSD if the strength of their intimate relationships had declined during deployment.

In their longitudinal study of more than 88,000 soldiers who served in Iraq, Milliken et al. (2007) found a fourfold increase in interpersonal problems from when they returned from deployment and a median of 6 months thereafter. The authors made special note of the cumulative burden of mental-health problems on family relationships and advocated greater mental-health resources for family members.

Baseline levels of perceived stress appear to have risen among Army spouses in recent years. The recent Army “Gold Book” indicated that more than half of all spouses reported experiencing stress in 2010 (56%, up from 46% in 2006) (Department of the Army, 2012). Supporting the notion of relatively high baseline rates of stressors, almost half of the spouses (44%) reported concern about finances, and two-thirds reported that they had less than $500 in savings accounts. More than half of the spouses were employed or were looking for work. Finally, 19% of spouses who responded indicated that they were in counseling, mostly for stress, family, and marital issues (Department of the Army, 2012).

Evidence assembled so far from both prior and current wars suggests that the likelihood of negative consequences for families rises with the amount of the service members’ exposure to traumatic or life-altering experiences. Thus, military service by itself does not appear to significantly raise the probability of negative outcomes (MacLean and Elder, 2007), and the same appears to be largely true for uneventful deployments lacking exposures to trauma (although traumatic exposures can occur not only with combat but also with duties related to peacekeeping and natural disasters (Allen et al., 2010). In contrast, deployment to combat zones has been found to significantly predict a variety of negative outcomes, including marital conflict and intimate partner violence (IOM, 2008). When service members display negative psychologic symptoms, the likelihood of negative consequences for families rises substantially (de Burgh et al., 2011), and families who experience the injury or death of service members are almost certain to experience at least some negative consequences.

Deployment and Married Couples

The health of marriages is typically assessed in research by two key indicators: marital quality and marital dissolution, which refers to the end of the marital relationship, typically via divorce (Karney and Bradbury, 1995). Although marital quality is difficult to measure, to date, measurements have focused primarily on the levels of satisfaction expressed by each partner (Knapp and Lott, 2010). Ideally, stable marriages have not only avoided dissolution, but also avoided separation or consideration of divorce, although studies vary in which of those elements are included (Karney and Bradbury, 1995). Dissolution, although relatively straightforward to measure, is a limited indicator of marital health because divorce is only the outcome of a lengthy and uncertain process.

In this section, we review research related to the impact of deployments on marital quality and marital dissolution.

Marital Quality Throughout the Deployment Cycle

The IOM (2008) found strong evidence that service members returning from deployments to combat zones were more likely to have marital problems, including intimate partner violence, than people who were not deployed and that this pattern was particularly strong when veterans had been diagnosed with PTSD. Evidence based on studies of Vietnam veterans was judged insufficient to conclude the existence of a causal relationship between deployment and marital conflict or marital dissolution.

On the basis of the perspectives of service members themselves, marital quality in the military population appears to have declined in the past decade. Data gathered from service members during deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, as part of the MHAT research program, revealed a steady downward trend in marital satisfaction each year between 2003 and 2009, from 79% agreeing or strongly agreeing that they were satisfied with their marriages in 2000 to 57% giving similar reports in 2009 (MHAT-VII, 2011). The declines were limited to enlisted members and were largest among junior enlisted males (pay grades E1 to E4). Service members’ reports that they intended to seek a divorce also rose from 12.4% in 2003 to 21.9% in 2009, again being much more evident among junior enlisted members. The 2006 MHAT report (MHAT-IV, 2006) indicated that problems with infidelity rose from 4% to 15% between 2003 and 2006, and marital problems more than doubled—from 12% to 27%.

Several studies suggest that marital quality following deployment is in part a function of quality before deployment (Nelson Goff and Smith, 2005; Rosen et al., 1995). Nonetheless, reasons for declines in marital quality are complex, and research results so far are mixed, particularly with regard to which mediators and moderators are most consequential for which people under which conditions (de Burgh et al., 2011).

Researchers have articulated several concepts evident throughout the deployment cycle—ambiguity and uncertainty, relationship connection, and communication—that characterize the nature of the relationship between military service members and their spouses and that influence their experiences (Sahlstein et al., 2009; Wiens and Boss, 2006).

Ambiguity and uncertainty are dominant aspects in the lives of military couples. Before and following deployment, the service member may be physically present but psychologically absent at least to some extent, while during deployment he or she is physically absent but psychologically present (Sahlstein et al., 2009; Wiens and Boss, 2006). In a study of 50 Army wives with current or recent experience with deployment, Sahlstein et al. (2009) found that separations related to training before the deployment heightened concerns about relational uncertainties (for example, concerns for the future of the marriage), and wives often responded by either expressing support or distancing themselves communicatively from their husbands (for example, by being silent or starting arguments). In a longitudinal study of Army reservists by Faber et al. (2008), ambiguity led to worries about the safety of the service member, how to handle challenges at home, and how to react to one another following return.

Baptist et al. (2011) interviewed 30 soldiers and spouses (not married to each other) in Army couples who had experienced one deployment to OIF or OEF. They used both open-ended and quantitative measures of the perceived impact of deployment on their marriages. Because of ambiguity about how to reintegrate service members into household duties following deployment, spouses sometimes continued to manage tasks as they had during the deployment, suppressing their personal needs or preferences. The researchers labeled this a maladaptive process because it complicated reintegration. Both reservists and spouses in the Faber et al. (2008) study reported similar hesitancies.

Using a cross-sectional convenience sample of 220 service members living in 27 states who had returned from deployment in the past 6 months, Knobloch and Theiss (2011) examined relational uncertainty (lack of confidence in self, partner, or relationship) and interference from partners (perceptions that partners are making it harder to achieve goals by disrupting routines). Service members who were dissatisfied with their relationships were more likely to report symptoms of depression but only if they felt uncertain about their commitment to the relationship and perceived their partners as interfering with their plans and activities.

For military couples, preparing for deployment and deployment separation can affect feelings of closeness and connection, heightening feelings of relationship insecurity and feelings of a lack of connection to their partner that result in relationship distress. For example, in the Sahlstein et al. (2009) study, the primary tension that spouses experienced during deployment was between autonomy and connection, particularly as it related to parenting roles. Spouses needed to feel independent enough to assume primary responsibility for parenting but also needed to feel sufficiently connected to their partner for support.

Permeating almost all accounts of deployment-related experiences are themes related to communication. Before and during deployment, families reported dissatisfaction with the

communication they receive from the military about the logistics of deployment and the welfare of the deployed service members (SteelFisher et al., 2008). During deployment, service members may lack access to communication facilities, and service members and spouses must make difficult decisions about what information to share and, given the wide array of communication modalities now available, how and when (Mulligan et al., 2012). Following return, service members and their partners must negotiate reintegration of the service member into the daily operations of the family and renew their intimate relationships (Baptist et al., 2011).

In the following sections, we describe a range of concerns and impacts as they relate to different stages of the deployment cycle.

Marital Quality Predeployment Before deployment, families must make legal, logistical, and emotional preparations for separation and the possible injury or death of their service members (McCarroll et al., 2005). Although it is logical that families would find this period difficult, few prospective studies of family members have been published.

Studies of service members indicate that concerns about their families are an important element of their predeployment experience. Findings from a study of deployment during the first Gulf War (Kelley et al., 2001) suggested that Navy parents anticipating deployment suffered from separation anxiety, particularly mothers (whether married or single). Polusny et al. (2009) surveyed 522 service members in the Army National Guard about 1 month before deployment, comparing responses of soldiers who had or had not been previously deployed for OIF or OEF. Results showed that service members were on average in good mental health and that soldiers with or without prior deployments were similar in their levels of concern about the impact of the separation on their families. McCreary et al. (2003) surveyed 180 members of the Canadian military 48 hours before departure for a peacekeeping mission in Bosnia and found that selfreports of family concerns explained more than half the variability in measures of depression, hyper-alertness, anxiety, and somatic complaints.

Service members also worry about their partners’ ability to cope. The 2003 Air Force Community Assessment survey of over 30,000 Air Force members serving on active duty asked members to rate their spouses’ readiness to cope with deployment-related challenges. Approximately one-third of junior enlisted members and members married less than 3 years indicated that their spouses would have a serious or very serious problem coping with deployment. Protective factors included military-unit relationship quality, military leadership effectiveness, and tangible social support from community members (Spera, 2009).

Spouses themselves also reported elevated worries and psychologic symptoms prior to service members’ deployments, although baseline levels of these issues in the military spouse population are not well documented. For example, members of a sample of 295 Army active-duty-component spouses recruited from Family Readiness Groups shortly before departure of a Brigade Combat Team for deployment (response rate 33%) reported scores on the Perceived Stress Scale that were substantially above the community norm. One-quarter of the spouses reported scores consistent with mild depressive symptoms, another half reported scores consistent with depression, and one in 10 reported symptoms of severe depression. Almost all spouses (90% or more) reported two stressors: “feeling lonely” and concerns about the “safety of the deployed spouse.” Four additional stressors were reported by at least half the spouses:

“having problems communicating with my spouse,” “raising a young child while my spouse is not present,” “caring/raising/disciplining children with my spouse absent,” and “balancing between work and family obligations/responsibilities.” Levels of depression were not related to number of stressors or prior deployments or number of children at home (Warner et al., 2009).

During Deployment

Relationships are often a worry for military members during deployment. Since 2003, family separation has consistently been among the top concerns of service members stationed in Iraq and Afghanistan and has been more strongly related to mental health problems than to any other concern (MHAT-V, 2008). A study of Navy sailors assigned to carriers showed that concerns about the children, and especially the marriage and the spouse, were expressed by substantially more participants during deployment and following return than before deployment (McNulty, 2005).

Hurley (2011) observed in a study of 129 Army spouses that a substantial proportion developed heightened rejection sensitivity partway through deployment, fearful that their deployed partners had decided to leave the marriage. These fears were significantly and negatively related to relationship adjustment, even though participants could identify no precipitating reason for their fear; fears also appeared to increase with cumulative months of separation.

Hinojosa et al. (2012) delved into communication difficulties experienced by 20 reservecomponent members of the Army and Marine Corps during deployment, exposing specific challenges related to expressions of emotion. According to the participants, each partner’s worry about the other led them to withhold information because of fears about revealing their own vulnerability or exposing vulnerability in their partner. The diminished familiarity with one another’s day-to-day lives created a sense of disconnectedness and additional difficulties between spouses.

Baptist et al. (2011) observed many of the same patterns, including the tension between spouses who not only engaged in high levels of contact to maintain strong emotional connections but also limited information to insulate one another from stressors at home or in the war zone. When spouses chose not to disclose stressors they had experienced, they foreclosed the possibility of receiving support from their partners. Similarly, Lara-Cinisomo et al. (2011) found that at-home caregivers who experienced difficulty expressing feelings to their deployed partners reported lower satisfaction and more hassles in their relationship. Earlier, Bowling and Sherman (2008) suggested that service members and their family members coped with the stresses of deployment by suppressing their emotional responses and that this suppression could impede processes of reconnecting with one another after return. During the current conflicts, the prospect of possible future deployments and separations might complicate the reestablishment of intimate relationships.

Mulligan et al. (2012) and others have observed that access to immediate communication with home during deployment can present challenges. Although it offers a practical and immediate way for service members to participate in family life, it also might involve service members in solving problems that could be resolved without their attention. The authors suggested that service members and spouses be taught strategies to determine how to make the best choices of methods, content, and timing of communication. Carter et al. (2011) examined

the communication of 193 Army couples characterized on average by high levels of marital satisfaction during deployment, including both frequency and type of communication (interactive, such as instant messaging and telephone calls; and delayed, such as emails, letters, and care packages). Many of the couples exchanged emails, instant messages, and phone calls daily and typically exchanged letters and care packages once or twice per month. More than half also used video instant messaging once per month. Results showed that service members reported lower levels of PTSD symptoms following deployment when they had communicated more frequently with their spouses during deployment but only when marital satisfaction was high and only when delayed forms of communication, such as letters, emails, and care packages, were used.

In the MHAT studies, length of deployment was positively correlated with the percentage of deployed service members who indicated that they planned to obtain a divorce or to separate after their return; for example, the MHAT-V study estimated that about 6% of noncommissioned Army officers indicated plans to divorce at 1 month of deployment, compared with over 20% at 15 months of deployment (MHAT-V, 2008). Plans to divorce or separate also appeared to be inversely correlated with pay grade: The MHAT-V study reported that, in 2007, 17.0% of junior enlisted soldiers deployed for 9 months were considering getting a divorce, compared with 12.3% of noncommissioned officers and 3.6% of officers. Mulligan et al. (2012) studied 2,000 British service members during deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. They found that both family problems (death or illness of a loved one, financial problems, or problems with children) and home and relationship breakdowns were negatively related to mental health by a large amount. Although high military-unit cohesion and effective military leadership fully mediated the relationship between relationship breakdown and mental health, family problems at home could not be completely compensated for by unit cohesion or military leadership. In addition, perceptions of poor military support for families at home were negatively related to mental health regardless of combat exposure, unit cohesion, or effective leadership.

Several studies have presented empirical data regarding the logistic, psychologic, and economic challenges experienced by marital partners during deployment. Logistic challenges include maintaining a household with only one adult present, such as management of maintenance, repair, and financial activity; providing all necessary care for children; maintaining employment; and arranging medical care or other services that are affected by military regulations (for example, reserve-component families may need to change medical providers when TRICARE coverage begins and ends) (SteelFisher et al., 2008). SteelFisher et al. (2008) conducted telephone interviews early in 2004 with 744 Army spouses associated with units that were deployed to the Persian Gulf during the first 4 years after the event on September 11, 2001 (9/11). Some of them had experienced an unexpected extension of their partners’ deployment. Deployment-induced logistic problems included difficulty in communication (sent and received) with the deployed members (41.0%), problems with household and car maintenance (29.0%), and problems finding child care (16.2%). Chandra et al. (2010a) and Lara-Cinisomo et al. (2011) surveyed over 1,000 at-home caregivers of children ages 7 to 17 who applied to have their children attend “Operation Purple” camps and conducted qualitative interviews with 50 participants. Baseline data were gathered during the summer of 2008; followups were conducted 6 and 12 months later. More than half of the caregivers surveyed reported one or more of the following logistic challenges associated with deployment: taking on more responsibilities at home; helping children deal with life without the deployed parent; spending more time with children on homework; and talking to teachers about children’s school performance. A

substantial proportion of spouses (30–50%) relocated during deployment. Proximity to extended family members increased, but it meant leaving local military services and causing children to change schools and living arrangements (Flake et al., 2009).

Psychologic challenges experienced by both service members and their spouses include fears for the safety of the service member, feeling anxious and overwhelmed by deploymentrelated challenges and responsibilities, worry about children, and concerns about military leadership, as well as vulnerability to additional stressors that might arise. In SteelFisher et al. (2008), the most common adverse effects of deployment on well-being that were reported by spouses were psychologic: loneliness (78.2%), anxiety (51.6%), depression (42.6%), and fears about personal safety (23.6%). A notable minority of the sample reported adverse perceptions of the military, the most commonly cited problem being lack of accurate information surrounding the timing of deployment, given that an unexpected extension had occurred (48.4%). According to Wright et al. (2006), fear of injury or death constituted major factors in the psychologic health of spouses throughout the deployment cycle, but especially before and during deployment. Existing data suggested that these concerns and fears tended to center on military training and leadership, the possible injury or death of service members, and concerns about managing on their own if that occurred.

In Chandra et al. (2010a), approximately half of the at-home spouses reported feeling that people in the community did not understand what life was like for them, particularly if they were affiliated with the reserve component. In addition, difficulties associated with new household duties were associated with increased anxiety and feelings of being overwhelmed (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2011). Chandra et al. (2010a) also found that emotional well-being declined over time among caregivers who were experiencing deployment, but well-being improved if deployment ended during the course of the study. Overall, there were several indications in Lara-Cinisomo et al. (2011) of the same sample that reserve-component families were more likely than active-component families to experience deployment-related difficulties. For example, caregivers in both National Guard and reserve families reported significantly greater household and relationship hassles, and caregivers in National Guard families reported poorer emotional well-being.

Allen et al. (2011) studied 300 couples with active-duty Army husbands and civilian wives who experienced a deployment within the previous year. Top concerns during the year for both husbands and wives were exposure to combat and the effects of the deployment on children. Husbands’ other strongest concerns pertained to sexual frustration; wives’ other strongest concerns pertained to loneliness and staying in touch, injury and fear of death, and reintegration and fears about potential changes in the service member. Infidelity was not a major concern reported by either husbands or wives.

Economic challenges associated with deployment can include loss of spousal employment or difficulty paying for child care or other household services usually provided by the deployed family member. Reserve-component members experience small income increases on average, although some lose income during deployment (Angrist and Johnson, 2000). In the SteelFisher et al. (2008) study, spouses of service members experiencing a deployment extension were more likely to report problems with work and to have scaled back or left work; they were also more likely to report problems in their marriages than spouses who did not experience an extension. Reported problems with overall health (21%) and perceived effects on jobs (18%) were more prevalent than financial problems (12%) or problems with their marriage (10%).

Marital Quality on Return from Deployment

Many of the same adjustments and role reallocations that must be completed as deployments begin must be completed again when service members return home (Bowling and Sherman, 2008; Pincus et al., 2001). Studies conducted after return from deployment emphasize the implications of psychologic symptoms of service members, but many other aspects of the reintegration experience may be consequential for adults and children.

Following World War II, Hill (1949) recognized that families’ experiences following reintegration were partially a function of their experiences and behavior during deployment. Some families appeared to function exceptionally well during deployment, “closing ranks” as if the deployed service member was unneeded or irrelevant; other families had great difficulty continuing to perform even basic tasks in the absence of the service members. Families who seemed to function best were those that closed ranks only enough to fulfill important tasks but not so much that there was no place for the service member upon his return. Research conducted during the Vietnam era reinforced these observations, demonstrating that families who maintained the service members’ psychologic presence during deployment seemed to adapt more effectively when difficulties occurred (McCubbin et al., 1975).

Although most studies fail to measure positive consequences of deployment, the Rosen et al. (1995) study of Army couples who experienced deployments associated with Operation Desert Storm in Iraq found that the five most common reunion events were positive: the soldier was pleased with the spouse’s handling of finances or running of the household, the couple became closer, the spouse became more independent, and the soldier did more chores. All positive events were reported by at least one-third of the sample. The five least common reunion events reported by no more than 10% of the sample were the following: the spouse became more dependent, the soldier was critical of the spouse’s handling of finances, the soldier resented the spouse’s new friends, and the spouse resented the soldier’s new friends.

Following deployment, the couples in Baptist et al. (2011) who had been able to maintain the ability to exchange mutual support with their partners also were more likely to report closeness in their marriages. Religious faith and belief in the importance of the military mission also were helpful. However, participants also reported suppressing, avoiding, or restraining sexual behavior with their spouses, all of which interfered with marital closeness (Baptist et al., 2011).

In a review of existing literature about reintegration following war-related separations, Vormbrock (1993) found that longer separations were related to more distress, detachment, and damage to the attachment relationship. Although both service members and spouses tended to engage in contact-seeking behavior, home-based spouses were more likely than service members to display detachment and anger. Rosen et al. (1995) gathered data from 776 Army wives 1 year after deployments to Operation Desert Storm to test Vormbrock’s conclusions. Both Vormbrock and Rosen et al. found that separation distress was heightened by stressful events during the separation but lessened when adults had access to alternative attachment figures; however, revival of childhood attachments, such as those to parents, could undermine the marital relationship.

After deployment, Sahlstein et al. (2009) observed, “soldiers and spouses often found themselves struggling to know how, when, and what to communicate with one another.” Families who were able to achieve a quick “return to normal” had maintained open lines of

communication, working as a team throughout the deployment. In most couples, however, there were mismatches between the service member’s willingness to share and the spouse’s willingness to hear.

Baptist et al. (2011) also found that both husbands and wives reported withholding information from their spouses in efforts to protect them from distress. Wives reported continuing to perform household duties following husbands’ return from deployment when they would have preferred greater involvement by husbands, and both husbands and wives reported restraining sexual desires. Although well intentioned, these decisions usually were made without consulting the partner about his or her preferences. Nelson Goff and Smith (2005) also observed that couples who were unable to reconnect following deployment were a function of both prior marital problems, such as infidelity, and difficulties in sharing information, exchanging comfort, and supporting each other.

Although reintegration processes are typically described as occurring over time, few studies have empirically documented the sequence, durations, or content of these processes, particularly as they relate to families. In several studies, members of families affiliated with the National Guard and reserves have reported greater difficulties or poorer outcomes associated with deployment (Chandra et al., 2010a; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2011). Faber et al. (2008) observed that reservists experienced prolonged ambiguity about their family roles and greater adjustment difficulties when return to the civilian workforce did not go smoothly. Civilian spouses and children might need to change medical providers, and civilian communities might be poorly prepared to serve military families (Huebner et al., 2009).

Summary of the Impact of Deployment on Marital Quality

In summary, as a result of deployment, marital quality is affected by psychologic challenges, including worry and uncertainty, that appear more prevalent than logistic issues (for example, managing the household) or economic difficulties (for example, loss of spousal employment). Some stressors are specific to a particular phase of the deployment cycle (that is, predeployment, during deployment, and postdeployment), and may dissipate as families move through the deployment cycle (for example, worries about a service member’s safety during deployment may lessen upon returning home). Others stressors are evident throughout (for example, communication issues) and may be a chronic symptom in a couple’s relationship. Male service members and their wives share many of the same concerns, such as concerns about the well-being of children and the service member’s safety, but also have separate ones. Dominant concerns among male service members include worries about the impact of separation on their families and worries about their spouses’ ability to cope with deployment-related challenges, including loneliness and household responsibilities. (The concerns of female service members are probably similar; however, there is a lack of studies of female service members to confirm the similarity.) The most common stressors among female spouses include feelings of loneliness, fears about their spouses’ death or injury, raising children alone, and problems communicating with their spouses. Spouses who are depressed and families that are members of the reserve component are more likely to experience deployment-related challenges. Families may also have positive experiences as a result of deployment, such as family bonding and increase competence in family functioning. Important to the understanding of the impact of deployment on marital quality is knowledge about what issues—individual or relational—may have been preexisting and not a symptom of deployment per se. Epidemiologic research that characterizes military

spouses irrespective of their experiences with deployment is lacking. Other gaps in the research base are related to the normative course, duration, and sequence of stressors experienced by military families as a result of deployment.

Marital Dissolution

Many media outlets have reported “skyrocketing” divorce rates as a result of deploymentrelated stressors (Alvarez, 2007; Crary, 2005; Parsons, 2008), and such an expectation seems reasonable given lengthy and repeated family separations. The empirical evidence so far is mixed, possibly because insufficient time has elapsed for the consequences of deployment to have become fully evident.

As noted earlier, military divorce rates have risen in the past decade. This section examines several investigations that have been conducted to determine the role of deployments in these increases. Two explanations have been proposed to explain divorce rates in the military. According to the stress hypothesis, the stressors of military life erode the stability of marriages, suggesting a positive relationship between deployment and the likelihood of divorce. In contrast, the selection hypothesis suggests that the likelihood of divorce is tied to characteristics of the partners and their relationships (Karney and Crown, 2007) and thus would not increase because of deployments.

Data from prior wars are inconsistent. For example, Ruger et al. (2002) studied 3,800 veterans of World War II and the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam using data from the National Survey of Families and Households. Veterans married prior to the Vietnam War were no more likely to divorce than those married after, failing to support the stress hypothesis at least with regard to deployment-related separation. A consistent finding across wars and robust to statistical controls, however, was that exposure to combat did increase the likelihood of marital dissolution, consistent with the stress hypothesis. More recently, a large representative survey of military members (59,631) showed that deployment to Operation Desert Storm was associated with a statistically significant increase, by 4.2 percentage points, in later divorce rates of female service members (Angrist and Johnson, 2000), but no association occurred among male service members.

Contrary to the view that longer deployments raise the risk of marital dissolution, (Karney and Crown, 2007, 2011) found in a study of personnel records of over 560,000 service members who married in 2002–2005 that the longer a service member was deployed, the lower the risk of divorce or separation. Risk was lowest for individuals who would normally be thought of as the most vulnerable—those who had married younger and who had children in the home. These results were not consistent with the hypothesis that the stress of deployment undermines otherwise healthy marriages. The findings were preliminary, however, because they focused only on relatively recent marriages that were followed for only a short period.

The most recent analyses were conducted by Negrusa and Negrusa (2012), who calculated the likelihood of marital dissolution as a function of deployment, using a military longitudinal dataset spanning from 1999 to 2008. They found that deployment substantially increased the risk of divorce, with the effect being stronger for female service members and for service members who were sent on hostile deployments (typically, to Iraq and Afghanistan).

In summary, results are mixed regarding the reasons for the rise in divorce rates in the military over the past decade. Both selection effects (preexisting characteristics of couples) and

stress effects (increasing operational tempo and more hostile deployments) appear to be relevant factors.

Spousal Abuse

Family violence, which includes spousal abuse1 as well as child maltreatment, has become a focus of concern in the military. This section covers spousal violence in terms of prevalence, types of abuse, risk factors, health consequences of abuse, and treatment.

Prevalence and Types

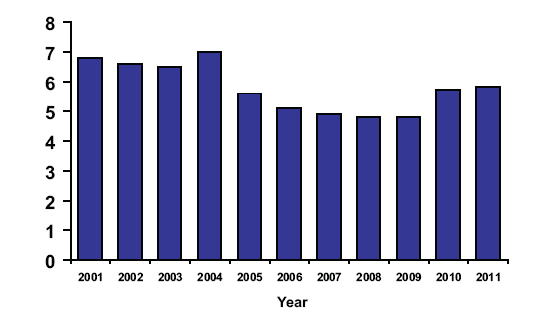

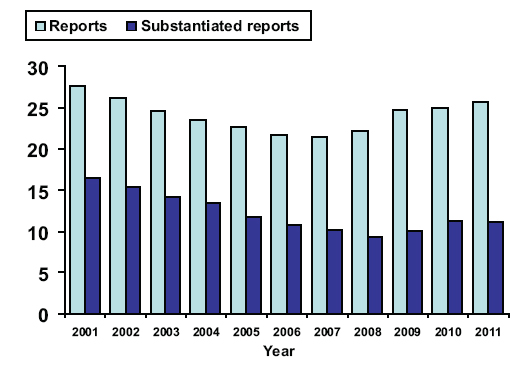

In 2011, the rate of substantiated incidents of spousal abuse was 11.1 per 1,000 couples (DOD, 2012c). This rate extends an upward trend that began in FY 2009. Before then, from FY 2001 to FY 2008, the rate had been declining (Figure 6.1). The data are compiled annually by DOD’s Family Advocacy Program (FAP), which was created in 1984 to identify, prevent, and treat family violence in the military. Because each report of spousal abuse reflects a single incident, there can be more than one report for a single victim. The abuser could have been an active-duty service member or a civilian. Finally, the data are not broken down by OEF or OIF; they are DOD-wide incidents.

FIGURE 6.1 Rate of spousal-abuse reports per 1,000 couples to the Family Advocacy Program, 2001– 2011.

SOURCE: DOD, 2012c.

Spousal abuse is distributed as follows: physical abuse accounts for 90% of spousalabuse cases; emotional abuse, 6–8%; sexual abuse, 0.5%; and neglect, 0.4% (Rentz et al., 2006). Two-thirds (67%) of abusers are male and one-third (33%) are female (DOD, 2012c). In FY 2011, there were 18 fatalities tied to spousal abuse (DOD, 2012c). The occurrence of spousal abuse, as compiled by the FAP, is probably an underestimate: incidents often go unreported out of concern for career implications of the active-duty service member or for victims’ concerns

__________________

1In this chapter, spousal abuse is synonymous with intimate partner violence and domestic abuse.

about their physical safety.2 The overall rate of spousal abuse in the military is similar to that of civilians, although the only study to address the comparison dates back to the 1990s (Heyman and Neidig, 1999).

Risk Factors

Deployment is perceived as the foremost stressor in the military, according to a 2005 DOD survey of some 16,000 male and female active-duty service members (Bray et al., 2006). Not surprisingly, deployment has been identified in the medical literature as a risk factor for spousal aggression in the aftermath of deployment. This finding was reported in a random sample of 26,835 deployed and nondeployed married active-duty members in the Army (McCarroll et al., 2000). The study also found that the likelihood of severe aggression rose with the length of deployment. With a short length of deployment (6 months), deployment was not found to be a risk factor in the first 10 months after return from deployment, but younger age was a risk factor (Newby et al., 2005b).

PTSD first emerged as a risk factor for intimate partner violence in Vietnam veterans. The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study found that one-third of the males with PTSD exhibited violence, according to their female partners (Kulka et al., 1990). A similar rate of violence was found among veterans with PTSD seen at a Veterans Administration (VA) medical center from 2003 to 2008 (Taft et al., 2009). In a recent study of Navy recruits, PTSD also was identified as a risk factor, having an odds ratio of 2.05, compared with recruits without PTSD (Merrill et al., 2004). Having PTSD symptoms of arousal and feeling a lack of control were the most robust predictors of aggression (Taft et al., 2009).

Substance use also has been found to be a risk factor for spousal abuse, according to a study of two Army databases of offenders, the Army Central Registry and the Drug and Alcohol Management Information System. The study found that 25% of 7,424 service members were under the influence of substances during the abuse incident. They were more likely than nonsubstance abusers to be physically violent and to exert more severe spousal abuse (Martin et al., 2010). A separate study found that the odds ratios for spousal abuse were 1.90 for alcohol problems and 2.02 for drug use (Merrill et al., 2004). However, in another study, alcohol use was unrelated to intimate partner violence among 248 married enlisted female soldiers, regardless of whether they were perpetrators or victims (Forgey and Badger, 2010).

In the only study on spousal abuse specifically in OIF and OEF service members, experiential avoidance—a coping strategy that seeks to avoid emotionally painful events—was associated with physical aggression perpetration and victimization in a study of 49 male National Guard members who returned from deployment to Iraq (Reddy et al., 2011).

Consequences and Treatment

Although data on the consequences of spousal abuse specific to military families are not available, in civilian studies, spousal abuse has been found to be associated with numerous negative outcomes. In studies of sheltered female domestic-violence victims, PTSD prevalence ranged from 51% to 75% (Golding, 1999; Street and Arias, 2001), depression ranged from 35% to 70% (Golding, 1999; O’ Leary, 1999), and substance-abuse disorders occurred in about 10%

__________________

2The figures are also underestimated because DOD maintains another database of law-enforcement cases of abuse—the Defense Incident-Based Reporting System, which covers the minority of cases that rise to a crime.

of victims (Helfrich et al., 2008). Similar findings were reported in a community sample of 94 women who were evaluated by diagnostic interviews (Nathanson et al., 2012). In the latter study, psychologic abuse was more likely to be associated with a mental disorder than with physical abuse.

The committee found little information about treatment of spousal abuse, which is a service provided by the FAP itself or in conjunction with local treatment providers. In 2010, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) concluded that, despite some improvements subsequent to the mandate to establish a DOD Task Force on Domestic Violence that was included in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000, “DOD lacks the sustained leadership and oversight of its efforts to prevent and treat domestic abuse that would enable the department to accurately assess the effectiveness of these efforts” (GAO, 2010).

The DOD monitors spousal abuse treatment by this one metric: the percentage of abusers who are not reported for spousal abuse within 1 year of program completed. As noted elsewhere in this chapter, the DOD reported that 97% of abusers who completed the program in FY 2011 were not reported (DOD, 2012b). Yet, no information is given about the content of the treatment program, how programs are evaluated, and their impact on the mental health of victims. The civilian literature indicates that many treatment programs for spousal-abuse victims or perpetrators are only minimally effective (Babcock et al., 2004; Nelson et al., 2004).

Summary

In summary, a service member’s psychologic issues are related to increases in marital distress, divorce, and disruptions in family life. Findings also suggest that the reverse is true: family relationships, both before and after deployment, can influence how a service member experiences PTSD in terms of coping with symptoms and symptom severity. Moreover, relationship quality may have an impact on treatment seeking by a service member. A spouse’s perception of a service member’s psychologic health (for example, perceptions of the apparent cause for symptoms or of the service member’s control over symptoms) influences the level of personal and marital distress experienced by the spouse.

Service members’ deployment is associated with increases in mental-health problems, particularly depression and anxiety, among spouses. Length of deployment and cumulative months of deployment predict increases in the likelihood of distress, but the number of deployments does not. Pregnant women with deployed partners experience high levels of stress and depression, particularly if they have other children. Although overall rates of spousal abuse in the military do not appear to be higher than those in the civilian population, there is evidence that the risk of spousal physical violence is higher after deployment, the risk increasing with the length of deployment.

The impact that the presence of children has on the psychologic well-being of a parent with a deployed spouse is somewhat ambiguous. Some studies have found that a parent’s worry about the well-being of their children and concerns over the logistics of providing care add to deployment-related stress. Other studies indicate that mothers and female spouses without children experience similar levels of distress. At least one study found that the presence of children is protective against depression in the stay-at-home parent. More studies are needed to understand the specific stressors faced by single parents serving in the Armed Forces.

Single Service Members and Their Families

Little attention has been paid by researchers to single service members who have experienced deployment and the degree to which family formation processes have been delayed or disrupted as a result. However, some of the same themes relating to deployment and marital quality discussed above are evident in a study of single service members living with their parents following return from deployment. Worthen et al. (2012) conducted qualitative interviews of OEF and OIF veterans living with their parents on the basis of the finding that 60% of young people return home to live with parents at some point. In most cases, veterans described their experiences as positive, and parents were helpful in recognizing health and adjustment problems. Distinct from the experiences of couples, adult children sometimes struggled with feeling treated as a child by their parents. Some service members were motivated by conflict with their parents to pursue school, a relationship, or work with undue haste. Women veterans interviewed in the study, a substantial proportion of whom had experienced military sexual trauma, had mixed experiences in terms of parental support, some experiencing ideal support but others experiencing conflict with or “smothering” by their parents. Few programs were available to educate or support parents in their efforts to assist their adult children.

Psychologic Health of Family Members

Among service members whose deployment experiences result in personality changes or psychologic symptoms and diagnosis, particularly PTSD, there are consequences for marital quality as well as specific psychologic effects on spouses and children. These are discussed below.

Psychologic Health of Spouses