This final chapter is based on the information and analysis in previous chapters of the report. It describes three potential prototypes to consider in redesigning the Consumer Expenditure Surveys (CE) and offers recommendations to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) from the Panel on Redesigning the BLS Consumer Expenditure Surveys on research and other inputs needed in redesigning the CE.

The CE has many purposes and a diverse set of data users. This is both the strength of the program and the foundation of its problems. The CE program tries to be “all things to all users.” The current design creates an undesirable level of burden on households and quality issues with its data. The Interview survey asks respondents for a very high level of detail collected over an entire year, with potentially counterproductive effects on their motivation and/or ability to report accurately. Because the Interview survey had been deemed not to satisfy all user needs, the program also includes the Diary survey. The Diary survey supplies much of the same information but at an even higher level of detail over a shorter period of time by using a different collection mode and a different set of respondents. However, Diary respondents appear to lack motivation to report consistently throughout the two-week collection period. Unfortunately, these two surveys are designed independently so the resulting data are not statistically consolidated to achieve their potential precision and usefulness.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) drives the level of detail asked in the

current CE surveys. The CPI is a Principal Economic Indicator of the United States and a crucial user of the CE. The CPI currently uses CE data for over 800 different expenditure items to create the budget shares required for those indexes. Most, but not all, budget shares come from the CE. In theory, a number of survey designs can provide the information required by the CPI, collecting a significant level of expenditure data without inflicting the level of burden on households that the current CE does. These designs, including a number of “matrix type” sample designs, involve asking each household only a portion of the total detail required while using weighting and more sophisticated modeling to produce the needed estimates. The data from these types of designs can provide the needed level of detail with appropriate precision needed by the CPI but with less burden on each household (Eltinge and Gonzalez, 2007; Gonzales and Eltinge, 2008, 2009). This family of designs would also meet most of the needs of government agencies in program administration and would allow BLS to continue to publish standard expenditure data tables. However, these types of designs are not optimal for other uses of the CE.

Researchers and policy analysts use the CE microdata to examine the impact of policy changes on different groups of households and to study consumers’ spending habits and trends. Many such uses are described in Chapter 2. These data users generally do not need the same level of item level detail required by the CPI. To them, the value of the CE lies in the “complete picture” of demographics, expenditures, income, and assets all collected for the same household. A comprehensive set of data at the household level allows microdata users to look at the multivariate relationships between spending and income in different types of situations for different groups of households. These data users also use the “panel” component of the CE, which provides the same information for a given household over multiple quarters. Parker, Souleles, and Carroll (2011) and Chapter 4 (“Feedback from Data Users”) further describe the usefulness of panel data in this type of analysis.

The multiple and divergent CE data uses are difficult to satisfy efficiently within a single design. Survey designs always involve compromise, and the current CE design tries to provide the breadth and detail of data to meet the needs of all users and then compromises by accepting the heavy burden and unsatisfactory data quality that emerges. The panel recommends that BLS redesign the CE only after rethinking what those compromises should be so that the trade-offs associated with redesign possibilities can be articulated and assessed within a well-developed priority structure. Determining these types of priorities for the CE is ultimately the responsibility of BLS, and is beyond what would be appropriate or realistic for the panel to undertake. Therefore, the panel makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 6-1: It is critical that BLS prioritize the many uses of the CE data so that it can make appropriate trade-offs as it considers redesign options. Improved data quality for data users and a reduction in burden for data providers should be very high on its priority list.

The panel recommends a major redesign of the CE once the priorities for a redesign are established. In its work, the panel concluded that many response and nonresponse issues in both the Diary and Interview surveys create burden and lead to quality problems with the expenditure data. The panel has concluded that less invasive cognitive and motivational corrections that might be made to improve recall and the reporting of specific expenditures would most likely increase overall burden. Since burden is inextricably connected with much of the survey’s problems, increasing it would be counterproductive.

Recommendation 6-2: The panel recommends that BLS implement a major redesign of the CE. The cognitive and motivational issues associated with the current Diary and Interview surveys cannot be fixed through a series of minor changes.

The charge to this panel was to provide a “menu of comprehensive design options with the highest potential, not one specific all-or-nothing design” (see Appendix B). Before BLS sets prioritized objectives for the CE, the panel’s most effective course of action is to suggest alternative design prototypes, each of which has a higher potential for success when enlisted to achieve a different prioritized set of objectives.

With that said, these prototypes share much common ground. The statistical independence of the current interview and diary samples is eliminated. The prototypes orient data collection methods toward an increasingly computer-literate society in which new tools can make the reporting tasks easier for respondents while providing more accurate data. The new prototypes are geared to increase the use of records and decrease the effects of proxy reporting. There is an increased emphasis on self-administration of survey components, while creating tools and an infrastructure that will monitor and support the respondent in these endeavors. The field representatives’ role will still be important in directly collecting data, but their role will grow to also provide support in additional ways. The panel proposes incentives that will increase a respondent’s motivation to comply and report accurately.

Finally and most importantly, all three prototypes propose new procedures and techniques that have not been researched, designed, and tested. The prototypes that the panel offers are contingent upon new research undertakings

and rigorous assessment. There is a lot of relevant background theory and research available, and the BLS research program and Gemini Project deserve praise for much of that work. However, the panel wishes to state clearly that the empirical evidence on how well each of the proposed prototypes would work is missing. As with the current CE surveys, the new prototypes include some diary-type data collection and some recall-type data collection. They include some self-administered data collection and some interviewer-assisted data collection. Notwithstanding, the new prototypes are sufficiently different from the current CE surveys that BLS cannot and should not use the current CE to extrapolate how well these prototypes will work in regard to response, accuracy, and underreporting. Considerable investment must be made in researching elements of the proposed designs, to find specific procedures that not only are workable but also are most effective. Some ideas will ultimately be successful, while others will be shown to have serious flaws. The critical point is that these prototypes are not operationally ready, and the process of selecting a prototype or components of a prototype for implementation should be based not only on BLS’ prioritization of goals of the CE, but also on empirical evidence that the proposed procedures can meet those goals.

Recommendation 6-3: After a preliminary prioritization of goals of the new CE, the panel recommends that BLS fund two or three major feasibility studies to thoroughly investigate the performance of key aspects of the proposed designs. These studies will help provide the empirical basis for final decision making.

Issues related to nonexpenditure items on the CE were discussed in detail in Chapter 5. These issues include such things as synchronization of expenditure and nonexpenditure items over similar reference periods, and collecting changes in employment status and other life events. These types of issues are important to the research uses of the CE. The panel offers the following recommendation that should be viewed within the context of BLS prioritization of the goals of the CE.

Recommendation 6-4: A broader set of nonexpenditure items on the CE that are synchronized with expenditures will greatly improve the quality of data for research purposes, as well as the range of important issues that can be investigated with the data. The BLS should pay close attention to these issues in the redesign of the survey.

With a new design, some existing uses of data may fall by the wayside. New and important uses will emerge. BLS has a talented and knowledgeable staff of statisticians and researchers who have worked with the CE

for many years. They understand the survey well, and the cognitive issues described by the panel are not a surprise to that staff. Using the framework that the panel has put forward, BLS statisticians will be able to pull together and test the specific details of a redesign that is appropriate for BLS’ collective priorities, budget, and time frame.

The rest of this chapter describes the three different prototypes, with many commonalities but each with its own focus. A more detailed discussion of those commonalities comes first, and then the report describes and compares the three prototypes. The final sections of the chapter begin a roadmap for moving toward a new design, including a discussion of important research issues.

PANEL’S APPROACH TO DESIGN AND THE COMMONALITIES THAT EMERGED

The panel considered many approaches to a redesign of the CE, and sorted through those numerous options by focusing on the following fundamentals:

- Improve data quality.

- Be mindful that the resources (both out-of-pocket and staff) available to support this survey are constrained.

- Be mindful that the survey processes have to be workable across the entire population of U.S. households—the more distinct processes that need to be designed for different population groups, the more resources will be required.

- Keep it simple—to the extent possible.

- Provide respondents with relief from the current burden level of the CE.

- Provide respondents with sufficient motivation to participate.

- Support the use of records and receipts.

- Support the current uses of the CE to the extent possible, and provide options in support of the prioritization of those uses in the future.

- Utilize newer data collection methodology and external data sources when supportive of the above fundamentals.

It is not reasonable for the panel to discuss all of the options that they considered and laid aside, but this section of the report is intended to illuminate the concepts and strategies that emerged with broad consensus during discussion of some of the major decision points in the panel’s deliberations. These commonalities can be seen in the design of the three prototypes.

Implement a Major Integrated Redesign

The panel came to an early conclusion that the cognitive issues with the existing surveys cannot be fixed with minor corrections, and it would be a mistake to focus independently on the various cognitive issues addressed in this report. The best approach is an overall redesign of the CE, with component pieces being shaped to minimize these cognitive problems at each phase of data collection.

The sample design for the new CE should be developed with a view toward integrating sample panels and data collection periods on a panel via statistical modeling in the estimation process, rather than generating independent estimates for each panel and data collection period. This method ensures that all data collected within the design can be fully utilized to minimize variance of estimates by capitalizing on the temporal components of the design or by integrating sample panels that collect different, but related variables from respondents. It may be possible that sophisticated sample designs along with appropriate modeling can provide needed data products with reduced burden on respondents. In investigating this possibility, it will be important to avoid creating household-level data with such a complicated structure of measurement error or statistical dependencies that it makes research use very difficult. At least, any reductions in possible use of the data need to be consistent with newly clarified BLS priorities.

Reduce Burden

The extreme detail associated with the current CE, and the amount of time and effort it takes to report those details, are major causes of underreporting of expenditures. These need to be significantly reduced for most respondents. The panel identified a number of ways to reduce burden, and more than one burden-reducing concept is included in each redesign prototype. Burden-reducing opportunities include (1) reducing the overall detail that is collected on expenditures, income, and/or assets; (2) asking details (or certain sets of details) to only a subsample of respondents, providing burden relief for the remaining sample; (3) reducing the number of times a household is interviewed or the number of tasks they are asked to do; (4) reducing the overall sample size and using more sophisticated estimation and modeling to maintain levels of precision; and (5) making response cognitively and physically easier. The panel spent considerable time identifying ways to reduce burden. It realizes that several of these options may be at odds with collecting a complete picture of income and expenses from each individual household over longer reporting periods. This is why it is essential for BLS to further clarify its priorities for data uses, recognizing that one survey cannot satisfy all of the possible data users.

Use Incentives to Increase and Focus Motivation

The CE surveys are very complex and burdensome, and even with the burden-reducing changes, the CE will remain a difficult challenge for households. Respondents currently have little motivation to respond, or more precisely to respond accurately, on the CE. The panel anticipates that respondents will have additional responsibility under a redesign to keep and record expenditures. The panel collectively agreed that respondents needed greater motivation to carry out these tasks and proposed that an incentive structure composed of monetary and nonmonetary incentives should be developed and implemented. The structure should be based on the amount of effort asked of a respondent and used to effectively encourage recordkeeping and reporting from those records. The panel speculated that the incentive payments would need to be fairly large to effect the needed motivation to report accurately. Components of an effective incentive program are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Support Accurate Use of Records

The panel envisions a redesign that will increase the respondents’ use of records in reporting expenses. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways. In the three prototypes, incentives are offered. There is an increased emphasis in each prototype to incorporate supported self-administration in a way that provides a structure to promote accurate reporting and increased use of records. This means incorporating flexibility to allow respondents to provide data at a time and in a way that is most convenient for them, and to answer questions in the order that they prefer. It means redesign of data collection instruments (whether self-reports and interviewer-driven, paper or electronic), technology tools, training, reinforcement, and incentives to facilitate recordkeeping. Minimizing proxy reporting in the reporting of detailed information is another improvement that can lead to more accurate reporting and use of records and receipts.

Redesign Survey Instruments

The new CE will need to redesign data collection instruments so that they simplify the respondent’s task. The panel sees a movement toward self-administered data collection with the field representative acting in a support role. However, the prototypes also incorporate interviewing by field representatives. Even though the panel envisions a wide acceptance of tablet-based interfaces, paper instruments will be needed for the foreseeable future. The current instruments may not suffice for this purpose.

Increase Use of Self-Administration

The panel discussed the advantages and disadvantages of various collection modes, and considered changes from the current CE surveys. The panel expressed concern about the shift in the current CE toward telephone data collection (primarily due to constrained resources), and felt this was not the best shift for data quality. The panel’s final recommendations move toward self-administration of these complex surveys. There are several reasons for this shift. The first is to encourage the use of records as discussed in the paragraphs above. This mode allows respondents to provide data in a way and at a time that is most convenient for them. When paired with an appropriate incentive structure, it can encourage respondents to take the time needed to use those records and receipts. A second reason is to take advantage of newer technology that can allow consistent, remote monitoring of self-administered data collection without the cost of having an interviewer present.

Reduce Proxy Reporting

The current CE surveys use proxy reporting because of the additional cost associated with working separately with multiple survey respondents within a household. The panel looked for solutions that will allow (and encourage) individual members of a household to report their expenditures without the accompanying increase in cost. The solution is a shared household tablet that each member of the household can use to enter expenses, but there is still a “primary household respondent” who oversees the entire process. This solution does not provide confidential reporting, and thus does not solve the problem when household members are reluctant to share details of certain expenditures with other household members. However, it does have the potential to eliminate much of the current proxy report process with minimal added cost per household.

Utilize Newer Data Collection Technology

The time is right to emphasis new technological tools in data collection. This is an essential component of the panel’s concept of supported self-administration. The panel discussed many technological alternatives and found one tool that was particularly appealing to the panel across a variety of designs—the tablet computer. The panel proposes the use of tablets in each of its redesign prototypes as an effective data collection tool. Lightweight and easy-to-use tablets represent stable (robust) technology, are commonplace, feature more than sufficient computing power, and are economical in price. The panel envisions that the tablet would sit on the

kitchen counter and be used by multiple household members in a “shared” approach to recording expenditures.

The panel also considered such alternatives as Web-based data collection, smart phone apps, and portable scanners for receipts. All are interesting tools and potentially could be used together in a redesigned CE. However, the panel stuck with its fundamentals—keep it simple and be mindful that the survey processes have to be workable across the entire population of U.S. households and that each additional approach (tool) will require additional resources to build and support. The panel looked for the one tool with the most potential.

Web data collection is not that tool. The Bureau of the Census (2010) estimated that only 44 percent of all U.S. households had Internet access either within or outside the home. This percentage varied greatly by household demographics and income. So requiring Internet access to use the electronic instrument would relegate the majority of households to the “paper” option. Additionally, building high quality Web-based instruments that work on multiple platforms (different computers, different browsers, high-speed versus dial-up Internet access, smart phone browers) can be very resource intensive. By providing the tablet to the household, BLS would be developing for a single platform, and the panel hypothesizes that a substantially greater percentage of households will be able to use the tool than if BLS relied on Web collection.

The panel saw similar issues with using smart phone apps—lack of coverage of the population of households, and considerable variability in hardware and software platforms. These devices are growing in popularity, but BLS would have to develop and maintain multiple versions even for use within the same household.

Portable scanners would allow respondents to scan receipts and upload them to a waiting file. These devices could be used along with the tablet PC for use in recording receipts. However, the array of formats and abbreviations that are used on printed receipts would likely require considerable intervention after the scanning to properly record each expenditure. Adding these scanners to the household would also require additional training.

The use of technology tools, and the tablet PC in particular, is discussed in more detail later in this chapter. The panel will recommend that BLS begin using this one simple tool, knowing that its implementation will be challenge enough for the short run.

Use Administrative Data Appropriately but with Caution

The potential use of external records or alternative data sources as a replacement or adjunct to current survey data for the CE is often raised in discussions of a CE redesign. Whether at the aggregate or the micro level,

the appeal of “readily available” information appears, at first glance, to be low-hanging fruit. Although such information might hold great promise, upon closer inspection the panel also realized that use of these data is accompanied by increased risk and significant resource outlays. There is a cost/quality/risk trade-off that needs to be fully investigated and understood.

The panel discussed the potential use of these external data at the micro level and identified several concerns: Permission from household members to access such things as personal financial data, utility bills, and shopping data (loyalty card) would be difficult to obtain and thus replace only a small percentage of survey data; BLS would have to develop an in-house infrastructure to access and process data from each external source (this would be a significant drain on available resources); and BLS would have to continue to field a complete survey for the majority of households. That said, there are scenarios under which these data could be quite useful, particularly at a more macro level. However, caution is warranted. This subject is discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

Create a Panel Component and Measure Life Event Changes

Economic analysts utilize the panel component of the current CE in much of their research. The report incorporates a panel component (with data collection from the same households at a minimum of two points in time) within each of the three prototypes. Each design also includes a re-measurement of income and “life events” (such as employment status, marital status, and disability) at each wave. However, the panel components differ considerably from design to design in the length of the response period, and this will significantly affect their relative usefulness in economic research. Of the three prototypes described, Design B has the most comprehensive panel component, with three waves and a response period of six months for each wave. Design C has two waves with a response period of three months for each wave. Design A has two waves, but with more variable response periods for each wave.

In this section, the panel presents three specific redesign prototypes. All three designs meet the basic requirements presented in Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) Data Requirements (Henderson et al., 2011). All three prototypes strive for increased use of records, incorporate self-administration (supported by the field representative, a tablet computer, and a centralized support facility) as a mode of data collection, and use incentives to motivate respondents. All three prototypes continue to use field representatives for interviewing and other support, and they all feature

either a single sample or integrated samples. However, each prototype is different—a better fit for a specific use of the data. BLS needs to prioritize the various data requirements of the CE and move toward a redesign that is best for its carefully considered prioritization. In overview,

- Design A focuses on obtaining expenditure data at a detailed level. To do this, the panel proposes a design with concurrent collection of expenditures through a “supported journal”—diary-type self-administered data collection with tools that reduce the effort of recordkeeping while encouraging the entry of expenditures when memory is fresh and receipts available. It also features a self-administered recall survey to collect larger and recurring expenses that need a longer reporting period. This design collects a complete picture of household expenses but with reports over different reporting periods.

- Design B provides expenditure data for 96 expenditure categories, rather than the more detailed expenses provided by Design A, but provides a complete picture of household expenditures over an 18-month period. It builds a dataset that would be excellent for economic and policy analysis. This design makes use of a recall interview coupled with a short supported journal. Two subsequent contacts with the same households are made over 13 months, repeating the original data collection using supported self-administration to the extent possible. This design also recommends that a small subsample be subsequently interviewed intensively over the following two calendar years, with collation of records, the use of financial software, and emphasis on a budget balance. This is discussed separately at the end of the description of Design B.

- Design C incorporates elements of both Designs A and B. It collects the detail of expense items as in Design A, while providing a household profile for six months. To do both, it uses a more complex sample design, collects different information from different samples, and requires more extensive use of modeling to provide expenditure estimates and the household profile.

Design A—Detailed Expenditures Through Self-Administration

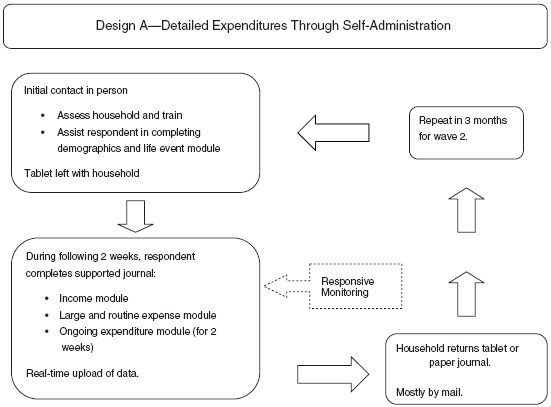

This prototype features a sample of households with two data collection waves, each of which features the concurrent reporting of expenditures over a two-week period using a supported journal. The design also incorporates a self-administered recall survey for larger, less frequent expenses. The design maximizes the use of supported self-administration and concurrent reporting of expenses. Figure 6-1 provides a flow outline of Design A.

The objective in Design A is to maximize the benefits that can be derived from self-administration in a new era of effective tablet computing and modular interface design. The idea is to simplify the respondent’s task, to allow respondents to provide data at a time and in a way that is most convenient for them, and to answer questions in the order that they prefer. In doing so, the panel believes that the survey can collect detailed expenditures accurately with reduced burden on respondents. The goals are to

- promote accurate reporting of detailed expenditure data by allowing sufficient time and space for careful enumeration of expenditures while using records and receipts;

- reduce the effort it takes to report those expenditures by providing support and technology tools; and

- reduce respondents’ tendencies (often implicitly encouraged in current methods) to estimate, guess, satisfice, or underreport.

Key Assumptions

Design A makes several key assumptions about the collection of consumer expenditure data:

- Detailed data for many items can best be obtained by supported concurrent self-administration, and a tablet-type device can assist in keeping the supported journal for most households.

- Interfaces for tablet-based applications (apps) will follow the best and newest principles of app design and testing, rather than simply importing or modifying current computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) technology and software.

- There will be a low refusal rate for use of the tablet given effective software and interface implementation.

- A two-week tablet-based reporting period for recording ongoing purchases is a plausible period. Households will be willing to participate in a second wave.

- For expenditures that must be recalled, different recall periods are appropriate for different categories of expenses.

- It is desirable to build alternative recall prompts or cues for different respondents who may have different ways of mentally organizing expenditures and/or different strategies for recalling them.

- The current set of income, asset, and demographic questions are reduced to only the essential items.

- Monetary incentives are available for respondents.

A single sample of households would be selected each quarter, with data collection initiated for a portion of the sample every two weeks within the quarter. A second wave of data collection for this same sample would take place in the subsequent quarter, with all responding households asked to participate for a second two-week collection period. Thus, for any given quarter, one independent sample would be initiated into wave 1 of the design, and a second sample would be brought forward from the previous quarter for wave 2 data collection.

Data Collection: Modes and Procedures

The predominant mode used in Design A is self-administered using a tablet PC. The data collection interface on the tablet would be modular, with flexibility on entering information in any desired order, with four modules:

- Demographics and Life Events Module: demographics and other information about the household. For wave 2, the questions would be modified to ask about key “life events” that might have transpired over the previous quarter.

- Ongoing Expenditures Module: for recording ongoing expenditures by household members during the two-week period.

- Large and Routine Expense Module: for reporting larger and routine expenses that may not be effectively measured during a two-week collection period.

- Income Module: household income, assets, and “labor force status” questions.

Navigation of the interface across and within the different modules would be streamlined and transparent for users of a wide range of backgrounds. The model for the interface would be “TurboTax” (commercially available tax preparation software) rather than the linear flow methodologies of today’s self-administered questionnaires. This means that the app would be built in modules and the user could choose to fill in the information in any order that is convenient. The user could also come back to any item and make a change at any time. Alternatively, the user (respondent) could choose to use a structured interview approach for moving step-by-step through the app.

During the initial in-person contact with the household, the field representative would identify the main “household respondent” and assist him or her with completing the Demographics and Life Events Module on the

tablet. The content of this first instrument would include standard demographics plus other items to assist in tailoring data collection instruments and estimation in the event that the household drops out of the panel, such as the number and age of household members, income bracket, purchasing habits, and use of online payments.

The first meeting also allows the field representative to assess whether the respondent (1) can be fully self-sufficient in using the tablet for later data collection, (2) will need additional support and monitoring during the next two weeks, or (3) would be likely to have severe difficulty with or refuse to use the tablet. The goal is to encourage the use of the tablet as much as possible while maintaining data quality.

Proxy reporting would be reduced by encouraging household members to record their own day-to-day expenditures in the Ongoing Expenditures Module during the two-week reporting period. The household respondent would guide the other household members in using this simple module. There would be no separate identification numbers to compartmentalize each member’s entries.

The household respondent would be asked to complete the Large and Routine Expense Module and the Income Module at his/her convenience during the two-week period. This allows the household respondent the time to review the questions and gather records. The Large and Routine Expense Module would ask about major purchases or periodic expenses such as automobiles, appliances, and college tuition. This module would also ask about routine expenses such as utility bills, mortgage payments, and health insurance payments. Respondents would be given alternative ways of entering the data that reflect reporting periods that correspond to their records. The Income Module would ask basic questions about household income and assets with a recall period that is most convenient for the respondent to report accurately. It would include information about changes in assets over the year.

At the end of the two-week period, respondents mail the tablet back. In some cases, a field representative visit may be needed to ensure the return of the tablet and capture key missing data. The Demographics and Life Events Module, the Large and Routine Expense Module, and the Income Module would be appropriately modified for a household’s second wave of data collection.

Frequency and Length of Measurement

Design A features two waves of data collection, each two weeks long, one quarter apart. All households are included in both waves of the panel. At a convenient time during the two-week reporting period, respondents

report larger and routine expenditures and income and assets via self-administered modules.

Recall Period

For the Ongoing Expenditures Module, household members enter purchases during the two-week period. Ideally respondents will enter data every day or almost every day. Different members of the household would be able to record their own expenditures. The centralized facility would be able to monitor and intervene if households do not enter data regularly or if there is evidence of poor data quality.

For the Large and Routine Expense Module, the recall period would vary between annual, quarterly, and monthly for different domains of expenditure, depending on which period has been shown to lead to the easiest and most accurate reporting. Within a single domain of expenditure, respondents may be given alternative ways of entering the data that reflect reporting periods that are easiest to provide based on the records to which they have access. In other words, the burden of recalculating amounts or recall periods for the needs of the survey is placed in the tablet software or centralized processing systems, and not the respondent.

The recall period for income and assets questions would be set to minimize measurement error and support estimation needs. This period is described as that which is most convenient for the respondent to report accurately while being close to the reporting period for expenditures.

Incentives

A guideline for incentive use is presented further in this chapter. In Design A, the panel estimates that $200 in incentives would be required per household ($100 for each two-week data collection period).

Role of Field Representative

The field representative’s role changes radically in Design A, from being the prime interviewer and data recorder to being the facilitator who encourages, trains, and monitors in support of the respondent’s thoughtful and accurate data entry. In this shift, the design attempts to change the burden and motivational structure of the current methods of collecting expenditure data. This entire process is described in more detail in “Using the Tablet PC for Self-Administered Data Collection” on p. 157. The role of the field representative will vary for households that use the paper-supported journal, and also across different tablet households depending

on their comfort with the technology, willingness to use records, and household composition.

Role or Expectations of the Respondent

From the respondent’s perspective, Design A makes it possible for the survey instrument to be tailored to his/her particular needs: expenditure context, comfort with technology, access to and format of records, preferences in reporting format, and preferred recall cues.

The design proposes a modern modular interface that has the simplicity, guidance, and intuitiveness of the TurboTax interface, rather than adhering to constrained traditional survey interfaces most often used today. This means that the app would be built in modules, and the user could choose to fill in the information in any order that is convenient. The user can also come back to any item and make a change at any time. Alternatively, the user (respondent) could choose to use a structured interview approach for moving step-by-step through the app.

The tailoring includes a paper alternative, with new forms of support for the respondent, if necessary. The design also gives respondents the opportunity to get 24/7 real-time support, exactly when they need it, as they record their expenditures and answer recall questions.

In this design, the respondent takes on the primary role of providing the most accurate data possible, supported by records to as great extent as possible. What differs from the respondent’s current role in the interview is that the respondent (after the initial meeting with the field representative) controls the time, pace, and order of data recording. In this sense, the design implicitly supports the idea that providing accurate data will take time and thoughtfulness. What differs from the respondent’s current role in the diary is that the respondent is provided an easy-to-use entry device augmented by ongoing interactive encouragement and support from both the interface and from remote support staff.

While in one sense, the respondent in the proposed design has greater responsibility (and support) than required in current expenditure surveys, in another sense the locus of responsibility is more distributed than before: among the respondent, field representative, and remote monitors (and, in a way, the interface designers and researchers). The respondent’s role thus includes being aware of and taking advantage of as much remote or in-person support as is needed to allow accurate data reporting.

Post–Data Collection Analysis

Data collected through the tablet (demographics, expenditures, and income/assets) would be complete and in an appropriate format for processing

by the end of the data collection period. Monitoring of the reported data allows for ongoing edit-checking during the two-week reporting period. The interface within the tablet converts data entered in the Large and Routine Expense Module and the Income Module to appropriate standardized reporting periods.

For paper households, data entry by the field representative or central staff would be required. Depending on the state of the paper materials, this could be very simple data entry or could include more complex decision-making from an envelope of saved receipts. Future efforts could create a smart data repository of the sort envisioned in the Westat proposal to reduce human effort of this sort, but the panel does not propose that here.

Infrastructure

This design would require

- purchase and inventory control/maintenance of tablet PCs for use in the field;

- new resources for app development and database management, not only for initial design efforts but also for ongoing continuing development and management. At least initially, BLS may want to consider outsourcing this function to organizations with experience in app development and management;

- new training to support field representatives in their new roles (and possibly new hiring practices to attract field representatives with different backgrounds or skills);

- new centralized survey management infrastructure for monitoring and support: case-flow management, tracking progress, managing interventions, providing positive reinforcements and managing incentives. This includes appropriate staff for technical support as well as staff who can support respondents remotely and staffing a 24/7 help desk that respondents could access by pushing a button on the tablet;

- fewer field visits requiring fewer field representatives in the field; and

- ongoing research to implement this prototype and to keep abreast of changes and future directions in technologies and technology adoption and of how these affect respondents’ recordkeeping and reporting proclivities.

The sample sizes and costs (data collection only) for Design A presented in this section are broad estimates for use only to compare across alternatives. More careful calculations were beyond the information and resources available to this panel. These calculations are based in part on a spreadsheet of 2010 CE costs provided to the panel. The panel used those costs to estimate for similar activities, and then calculated an estimated cost per sample case for the new prototype. Thus, these costs are for data collection only, and for data collection within a mature process. Estimates of sample size (net of 25% nonresponse) were then made that would keep to a neutral budget.

Assumptions:

- Cost per supported journal placement—$165.

- 85 percent of households would use tablet. Costs would go down with greater use of tablet.

- Cost of tablet—$200. It could be used 6 times, with an expected loss of 10 percent.

- Remote monitoring of responses—$100 per two-week supported journal.

- In-person monitoring—$150. Necessary for 10 percent of tablet households, and twice per each paper household.

- Incentives—$100 per two-week supported journal.

- Paper processing for paper households—$100.

Based on these assumptions, and remaining budget neutral ($16,000,000), the panel calculated the following projections for this prototype:

- Total cost = $16,000,000.

- Annual effective sample size (assuming 75% response) = 18,700.

- Average cost per sample = $853.

Meeting CE Requirements and Redesign Goals

This prototype meets the basic CE requirements laid out in Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) Data Requirements (Henderson et al., 2011). Additionally, it is designed to reduce burden, reduce underreporting of expenditures, and utilize a proactive data collection mode with newer technology. Table 6-1 provides greater detail.

TABLE 6-1 Meeting the CE Requirements and Redesign Goals with Design A

| Goal | Design A—Detailed Expenditures Through Self-Administration |

| Produce quarterly and annual estimates of 96 categories of expense items | The design collects data at a more detailed level of expenditures than the 96 categories. Collectively, the 26 two-week data collections over the year will provide annual and quarterly estimates of expenditures at a fairly detailed level. |

| Income estimated over the same time period | Income is reported for a period most convenient for the respondent to report accurately while being close to the reporting period for expenditures. Income, like expenditure data, may be modeled for the entire year. Income, assets, and “labor force status” are requested during both waves. |

| Complete picture for household spending | A complete picture of each household is collected for two two-week periods, as well as information on larger items and routine expenditures over a longer recall period. By developing a process of seasonal adjustment for the four weeks of expense reporting, it would be possible to make quarterly or annual estimates of expenditures at the household level. The accuracy of those estimates will need to be researched. |

| Proactive data collection rather than change at the margins | The focus of this prototype is proactive self-reporting. Some larger expenditures are recalled, but in a setting to encourage the respondent to think about the expenditures and look up records. |

| Panel component with at least two contacts | There are two contacts for each household, in adjacent quarters. |

| Reduced burden | The proposed design redistributes burden in current Interview and Diary methods to a supported journal with a modern tablet interface. Burden is reduced by making the response tasks easier and more intuitive. This prototype reduces the number of contacts per household. Incentives are used to reduce perceived burden. |

| Reduced underreporting | Focus on detail, the increased use of records, allowing the respondent to record expenses at a time best suited and in a way best suited to him/her, reduced proxy responding, and incentives to perform the task are expected to lead to a reduction in underreporting of expenditures. |

| Budget neutral | Sample sizes are calculated to maintain approximately the current budget level. |

Targeted Research Required

Many of the research requirements for Design A are common to the other two prototypes, and are discussed in more detail in “Targeted Research Needed for Successful Implementation of Design Elements” on p. 178. Research specific to this prototype includes studies that would develop

models that would estimate quarterly and annual expenditures and income at the household level from the four weeks of reported detailed data from the Ongoing Expenditures Module plus the data reported on the Large and Routine Expense Module.

Design B—A Comprehensive Picture of Expenditures and Income

This prototype attempts to collect income and expenses at the individual household level over 18 months. It features household respondents “recalling” expenditure data aggregated for the 96 categories of expenditures (discussed in Henderson et al., 2011) for the previous six months. It is anticipated that a more focused questionnaire with less categorical and chronological detail may take less time to complete than the current Interview survey. Coupled with three contacts instead of five, there is an expected overall burden reduction compared to the current CE Interview survey. If an effective supported journal can be designed, the same households in the sample would also be asked to participate in a one-week supported journal to collect detail on smaller expenses used primarily to disaggregate some expenses reported in the recall survey.

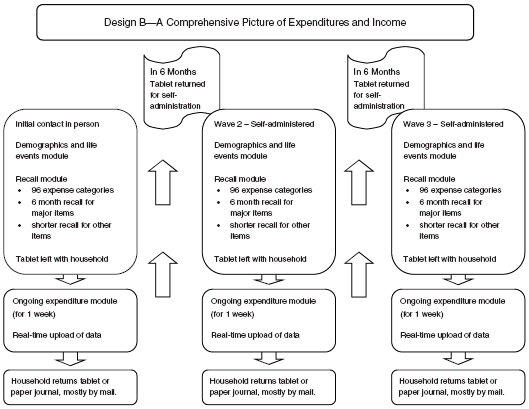

The initial contact for Design B is an in-person visit by the field representative to the household. The field representative would assist the respondent in completing a recall survey of expenditures on a tablet computer. The tablet would be left with the household for use in a one-week supported-journal concurrent collection of expenditures and then mailed back, similar to that described in Design A. The tablet would be returned to the household by mail in six months and again in one year to repeat the recall and supported journal in a self-administered mode. Figure 6-2 provides a flow outline of Design B.

Objectives

Design B has the following primary objectives:

- Rely on a basic recall mode of reporting, which has provided aggregate expenditure estimates in the past that were more in line with the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE).

- Redesign the recall questionnaire to collect expenditures directly from the respondent at a broader level of aggregation, rather than collecting the current level of detail and then calculating aggregates.

- Provide specific instructions to help the respondent estimate expenditures that cannot be recalled.

- Utilize technology to assist and support the respondent in filling in this redesigned questionnaire through a self-administered process in waves 2 and 3.

- Build data files well designed for economic research and policy analysis by providing a comprehensive picture of expenditure, income, and assets for each household for 18 months.

- Use a component subsample linked to the main sample that could be used to explore the accuracy of the overall data collection and provide an opportunity to collect data for more demanding research needs. It would employ techniques such as the prior collation of records, the use of financial software, and budget balancing. This component is discussed separately at the end of the description of Design B.

Key Assumptions

Design B makes several key assumptions about the collection of consumer expenditure data:

- The collection of “bounding” data is unnecessary and inefficient for the collection of accurate expenditure data in a recall survey.

- The value of the micro dataset flows primarily from the construction of expenditure data for relatively broad aggregates—for instance, the 96 expenditure categories for which CE tables are currently published—rather than an extremely detailed breakdown of those expenditures.

- A household can accurately recall aggregated expenditures for periods up to six months for some categories of expenditures. For other expenditure categories, respondents can approximate averages (e.g., average monthly spending for gasoline) that can be used to construct a full set of microdata for the entire six-month period.

- Household respondents will agree to remain in the panel for 13 months, with three data collection events during that period.

- The use of supported self-administration with the tablet, a central support facility, and the field representative allows most respondents to complete the redesigned recall questionnaire without the need for an in-person interview during waves 2 and 3.

- Households selected for the intensive subsample would be willing to participate in this more intensive data collection and are able, with assistance, to budget balance their annual finances.

To the extent these assumptions are valid, detailed microdata suitable for socioeconomic analysis can be obtained at the same time that the aggregate data objectives of the survey are met.

Sample Design

In Design B, a large sample of households is surveyed three times, at six-month intervals. To smooth the operation of the survey, one-twelfth of the households would be initiated each month. Once fully implemented, the workload in each month would be the initiation of a new survey panel, administration of the second wave of the survey to the households that had been initiated six months earlier, and administration of the final wave of the survey to the households initiated one year earlier. The field representatives are used intensively in the initial wave. If self-administered collection methods are successful, the field representative is used in the two additional waves only for households who need in-person assistance in completing the questionnaire.

In addition to a recall of expenses, each household would be asked to keep a one-week supported journal for the upcoming week. Thus, both recall and supported journal surveys are conducted on the same households, and repeated at six-month intervals for three repetitions.

Data Collection: Modes and Procedures

Design B collects recalled expenditure data, as well as demographic information, income, and assets. The first wave of collection is interviewer assisted, with the subsequent two waves relying on supported self-administration to the extent reasonable. As with Design A, survey instruments are presented through an interface on a tablet computer. The tablet interface follows the guidelines described under Design A and in “Using the Tablet Computer for Self-Administered Data Collection” on p. 157. Thus, the details are not repeated here.

In this prototype, the tablet is set up with three modules all designed for self-administration:

- Demographics and Life Events Module: demographics and other information about the household;

- Recall Module: for reporting expenditure, income, and asset data recalled or estimated for the past six months; and

- Ongoing Expenditures Module: for recording detailed, ongoing expenditures by household members during the one-week period of supported journal collection.

During the initial in-person contact with the household, the field representative identifies the main “household respondent.” As with Design A, the field representative assists him or her with completing the Demographics and Life Events Module on the tablet. The first meeting also allows the field representative to assess whether the respondent can be fully self-sufficient in using the tablet for data collection. The goal is to encourage the use of the tablet as much as possible in subsequent waves while maintaining data quality.

The field representative would then assist the respondent in completing the Recall Module reporting expenditures and income for the previous six months. This process not only obtains the needed data for this wave, but also trains the respondent on using the tablet and the specific modules in preparation for waves 2 and 3.

Following the completion of these modules, the field representative would ask the respondent to keep a concurrent supported journal for the next week (Ongoing Expenditures Module). Following the supported journal week, the respondent returns the tablet by mail.

Wave 2 takes place in six months and wave 3 in one year following wave 1. Respondents would be contacted a month ahead of the recall data collection and reminded to gather records and receipts. The tablet with the same data collection modules is used. Household respondents who were successful in using the tablet during wave 1 would be mailed a tablet for waves 2 and 3 to be completed without interviewer assistance. The “interviewer assistance” during wave 1 prepares them to complete this task. They are asked to complete all three modules and return the tablet following the supported journal week. Households that were not successful using the tablet in wave 1 would be contacted in person or over the telephone to complete waves 2 and 3.

Demographics and Life Events Module: This module includes standard demographics plus other items to assist in tailoring estimation in the event that the household drops out of the panel. Examples include the number and age of household members, income bracket, purchasing habits, and use of online payments. In waves 2 and 3, the questions would be modified to ask about key “life events” that might have transpired over the previous six months.

Recall Module: This module collects data on expenditures at a relatively broad level of aggregation based on variable recall periods. The objective is to obtain six-month estimates for each expenditure category. The assumption in this prototype is that reporting certain expenses (such as major durable goods, rent, and utilities) for six months would be relatively easy and accurate. For other recurring expenses such as groceries and gasoline,

for which shorter recall periods are appropriate, the respondent could make estimates of monthly averages of sufficient accuracy to be expanded to estimate spending for six months. Ultimately, all reported data would be expanded to a six-month estimate by the tablet app. The instrument would also include special prompts for expenditure categories that have been historically underreported, such as clothing, food away from home, alcohol, and tobacco. These prompts would include the types of expenditures and the possible locations of potential purchases.

Compared to the current CE Interview survey, Design B significantly curtails the number of questions both in terms of the breadth of categories (as discussed above) and the detail required in reporting those expenditures. For instance, the instrument would not ask in which month purchases were made, or sales tax, or information about the individuals for whom the purchase was made. These details add significantly to the burden in the current CE Interview survey.

Income, assets, and “labor force status” would be collected for each household for the same six-month period. Again, some estimation may be necessary based on current pay stubs and prior tax records.

Ongoing Expenditures Module: After completing Design B’s recall survey, households would be asked to keep a one-week self-administered supported journal. The supported journal would collect information on expenditure categories for which recall collection is more problematic and would provide additional detail that can be used to disaggregate totals. Thus, the supported journal would focus on specific categories of expenses. (However, research might indicate that it is more efficient to collect a complete record.) A paper-supported journal would be available for use when necessary, but the tablet would be the preferred mode.

Frequency and Length of Measurement

There are three waves of data collection at six-month intervals in Design B. Each wave uses a tablet computer with three modules. Wave 1 requires an in-person visit by the field representative with an “assisted” interview using the tablet for the Demographics and Life Events Module and the Recall Module. The tablet is left with the household for a one-week supported journal. In subsequent waves, the tablet is mailed to the household for self-administration of two modules plus the one-week supported journal. A household is in the sample for 13 months and recalled expenditure data are collected for 18 months. All recall and supported journal instruments are the same for different waves. The demographics module would be modified for use in waves 2 and 3 to ask about key “life events” that might have transpired over the previous six months.

Completing the Demographics and Life Events Module and the Recall Module is expected to take 30–45 minutes regardless of mode. The Ongoing Expenditures Module (supported journal) is expected to take 20 minutes per day.

Recall Period

The recall period for Design B’s Recall Module is six months. If appropriate, the recall period for some items can be less than six months, and the expenditures reported for the shorter period used to estimate spending for the full six-month period. For the Ongoing Expenditures Module (supported journal), the collection period is one week. The supported journal collects data on a daily basis, with little or no recall required.

Incentives

The panel estimates that an incentive payment of $100 would be made to households for completing each of three waves of data collection in Design B. Households that were unable to use the tablet and require in-person enumeration for each wave would receive an incentive of $50 per wave instead of $100.

Role of the Field Representative

In Design B, the field representative establishes contact with each household and secures cooperation. The field representative conducts the first interview by assisting the respondent with wave 1 data including household composition, demographics, and the six-month recall categories. Simultaneously, the field representative trains the respondent on the use of the tablet and its modules in preparation for waves 2 and 3. The field representative recruits the household into the supported journal collection, emphasizing the tablet-supported journal collection in the vast majority of cases. The field representative trains the respondent on the use of the tablet for supported journal collection. The field representative explains the incentive for filling in the supported journal, leaves the tablet and a mailer at the household, and departs.

After the initial in-person visit, ideally the field representative never visits the household again. In principle, the household faithfully fills in the Ongoing Expenditures Module (supported journal) and mails the tablet back in a timely manner, and the household respondent successfully masters using the modules on the tablet and agrees to complete waves 2 and 3 in a self-administered mode. The field representative may be called upon by the central office to intervene with a household, for example, to encourage

reporting on the supported journal for the entire week, to answer questions about the instrument, to substitute a paper-supported journal for the tablet-supported journal, or to pick up the supported journal. The field representative does not monitor the cases in the first instance, but intervenes only at prompting from the central office.

The role for the central office includes monitoring the cases on a daily basis, phoning the household to intervene if the supported journal is not filled in, and prompting field representatives if their assistance is needed. The central office also fills the role of first-line support for respondent questions, forgotten passwords, and the like. The central office will also re-initiate contact with the household in six months, mailing the tablet and instructions.

Role or Expectations of the Respondent

The respondent provides data three times in Design B. The first time, the respondent is assisted by the field representative for the recall categories, but then records concurrent expenditures with the supported journal items for a week. The respondent may need to use a paper-supported journal rather than the tablet. Whether the supported journal is a tablet or paper, the respondent is expected to mail it back to the home office. The assumption of Design B is that most respondents are willing to use the tablet throughout all three waves. The tablet is expected to make the respondent’s job easier.

Post–Data Collection Analysis

The spending for some goods over the previous six months would have to be estimated based on the spending during a shorter recall period. This could be as simple as doubling the expenditures reported for a three-month recall period, as Statistics Canada does for their interview survey. It is expected that the tablet app will make these adjustments. This design makes it easier for analysis because any modeling required for a complete record is done within the household, not across households.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure needs for Design B are similar to those in Design A and not repeated here.

Sample Size and Cost for Basic Component

The sample sizes and costs (data collection only) presented in this section for Design B are broad estimates for use only to compare across alternatives. More careful calculations were beyond the information and resources available to this panel. These calculations are based in part on a spreadsheet of 2010 CE costs provided to the panel. The panel used those costs to estimate for similar activities, and then calculated an estimated cost per sample for the new prototype. Thus these costs are for data collection only, and for data collection within a mature process. Estimates of sample size (net of 25% nonresponse) were then made that would keep to a neutral budget. Sample size and costs for the subsampled component are provided separately.

Assumptions:

- Cost per in-person recall module or interview—$325.

- 85 percent of households would use tablet. Costs go down with greater use of tablet.

- Paper households are contacted in person on each wave.

- Cost of tablet—$200. It can be used six times, with an expected loss of 10 percent.

- Remote monitoring of responses—$100 per wave per tablet household.

- In-person monitoring—$150, or $325 for full interview. Necessary for 10 percent of tablet households, and once or twice per paper household per wave.

- Incentives—$100 per wave per tablet household and $50 per wave when interview is required. Households participating in the intensive study would receive $150 per wave.

- Paper processing for paper households—$100 per wave.

Based on these assumptions, and remaining budget neutral ($16,000,000), the panel calculated the following projections for this prototype: (Sample size and costs for the subsampled component are provided separately.)

- Total cost = $13,900,000.

- Annual effective sample size (assuming 75% response) = 12,200.

- Average cost per sample = $1,138.

Meeting CE Requirements and Redesign Goals

Design B meets the basic CE requirements laid out in Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) Data Requirements (Henderson et al., 2011). Additionally it is designed to reduce burden and reducing underreporting of expenditures. Table 6-2 provides more detail.

TABLE 6-2 Meeting the CE Requirements and Redesign Goals with Design B

| Goal | Design B—A Comprehensive Picture of Expenditures and Income |

| Produce quarterly and annual estimates of 96 categories of expense items | All 96 categories of expense data are collected with three data points for each. |

| Income estimated over the same time period | Questions on income, assets, and “labor force status” are asked on each wave and for the same reporting period. |

| Complete picture for household spending | This prototype focuses on providing an improved picture at the household level over the current CE. Some items are collected in the recall module and some in the supported journal, but both are collected from the same households. Data adjustment (expansion) to the entire six-month period will be needed for items not collected or estimated for the entire six-month period. However, each household will have complete (or estimated) records for all 96 items. |

| Proactive data collection rather than change at the margins | The supported journal collection is proactive. The recall module is recall. |

| Panel component with at least two contacts | There are three contacts for each panel member. |

| Reduced burden | There are three administrations per household, instead of five for the current interview. The interview is less burdensome than the current CE in terms of length and in difficulty of task. However, the household is now expected to execute both the interview and the supported journal. Incentives are used to reduce perceived burden. |

| Reduced underreporting | This prototype makes the assumption that aggregating expenditures for recall over a six-month period will have less underreporting than an attempt to recall more detailed expenses over three months. Research is needed to evaluate this assumption. |

| Budget neutral | Sample sizes are calculated to maintain approximately the current budget level. |

Many of the research requirements for Design B are common to the other two prototypes, and are discussed in more detail in “Targeted Research Needed for Successful Implementation of Design Elements” on p. 178. Research specific to this prototype includes the following:

- investigate the assumption that a “bounding” interview is unnecessary to avoid telescoping and other issues;

- investigate the accuracy and completeness of aggregated expenditures for periods up to six months and for estimates of averages (e.g., average monthly spending for gasoline) used in this prototype to construct a full set of microdata for the entire six-month period;

- develop appropriate models to “disaggregate” aggregated expenses using data from the one-week supported journal; and

- develop successful methodology for a component that will use an intensive interview and process based on prior collation of records and financial software to achieve a budget balance for the year at the household level, as described below.

Intensive Subsample in Design B

Design Objectives: A relatively small subsample of households who have completed wave 3 of the basic component of Design B would be asked to participate in a more intensive process to provide a full picture of income and expenditures over two consecutive calendar years. The process uses paper and online records more intensively, encourages the use of financial planning software, and employs budget balancing to reduce discrepancies between expenditures and income net of savings.

As discussed in Chapter 5, the PCE is the primary but problematic benchmark for comparing the CE aggregate expenditures. This subsample would attempt to establish accurate measurements of expenditures, income, and assets at the household level for a year through a more intensive record– and budget balance–driven process. Besides establishing an improved benchmark for measuring the success of the data collection methodologies in the basic component, the subsample would inform how better to collect expenditures in the ongoing survey and measure the extent and organization of household recordkeeping.

Key Assumptions: Assumptions for Design B’s intensive subsample include the following:

- Households that have completed wave 3 of the basic component of this prototype are willing to participate in this more intensive process if selected for the subsample.

- Respondents, with the help of the field representative, can reach reasonable balance between expenditures and income less savings. Fricker, Kopp, and To (2011) found the actual balancing between income and expenses difficult in practice. However, Statistics Canada used this approach for a number of years before redesigning their survey in 2009, so there is likelihood that a workable prototype can be developed.

Sample Design: A relatively small subsample of households that have completed wave 3 of the basic component of this prototype would be selected for this component. Calculations in this report are based on a subsample of approximately 5 percent of the original sample.

Data Collection: Modes and Procedures: The initial wave of data collection would begin approximately two months following the wave 3 interview. A second wave of data collection would be one year later. Data collection is expected to be face-to-face. It may take multiple visits to achieve the required balance.

Expenditure and income data reported during waves 2 and 3 of the basic component would be available to the respondent and field representative to work together to bring things in balance. The goal of having a financial budget that balances would be explained up front to the household. The respondent would be encouraged to use financial software and supply records, and/or draw information from online financial sources, including credit card and bank accounts as is done by Mint.com (2011). Additionally, the respondent will be asked about loyalty card programs in which they participate, and will be asked to provide permission for BLS to obtain the household spending data captured within those programs. Categories of spending for which there are no records become the leftover or residual part of expenditures. The main survey instrument is then used to fill in the missing parts of expenditures over the year, keeping in mind the need for the budget to balance.

Frequency and Length of Measurement: This design features two waves of data collection, one year apart. All households in the subsample will be included in both waves. Income, savings, and expenditure data for one year are required for each wave.

Recall Period: This intensive process focuses on obtaining and using records of income and expenses. However, during the balancing process, respondents may be asked about expenses and income for the previous year.

Incentives: The panel understands that the effort required of a respondent to actively participate in the financial balancing activities is greater than for a recall interview. Therefore, it estimates that an incentive payment of $150 would be made to households for completing each of two waves of data collection, for a total of $300.

Role of the Field Representative: The field representative’s role in this component changes radically. He or she assists the respondent in sorting through available records of income and expenses over the year. The field representative would also work with the respondent to balance the household financial budget for the year, probing for additional income and/or expenses to bring the budget into balance.

Role or Expectations of the Respondent: The respondent is expected to be an active participant in this process to balance the components of the household’s financial budget for the year. This would include providing paper and electronic records, and giving permission to access credit card, banking, and tax records directly.

Post–Data Collection Analysis: N/A

Infrastructure: None specific for this component of Design B.

Sample Size and Cost: The sample size and costs (data collection only) presented here are broad estimates for use only to compare across alternatives. More careful calculations were beyond the information and resources available to this panel. These costs are in addition to the costs for the basic component of Design B.

Assumptions:

- Budget balancing process may take several interviews with the household and may require more experienced field representatives. Expected cost per household—$800 per wave, with $350 per refusal contact.

- Response rate—50 percent

- Incentives—$150 per household per wave.

Based on these assumptions, the panel calculated the following projections for this prototype.

- Total completed sample size per wave = 800.

- Average cost per household per wave = $1,300.

- Approximate total cost = $2,100,000.

Design C—Dividing Tasks Among Multiple Integrated Samples

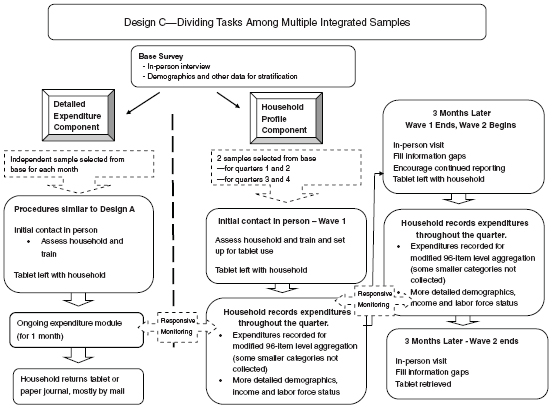

Design C utilizes a multiphase sampling design that empowers estimation and modeling to provide the needed data products with reduced burden on respondents. In doing so, it provides detailed expenditures similar to Design A. It provides a complete picture of household expenses and income as in Design B, but for six months (instead of 18) and only for a portion of households. It features supported self-administration using a tablet computer and data collection interfaces as described in the other two designs. Figure 6-3 provides a flow outline of Design C.

Design Objectives

The guiding principle behind Design C is to avoid asking every household in the sample to perform exactly the same tasks. By dividing up the tasks, the overall burden on an individual household is reduced. The totality of information is brought together through estimation and modeling. The power of this design relies on (1) achieving good correlation between the estimates from the base survey and the estimates from the later phases of data collection; (2) developing effective models involving covariates such as demographic characteristics to connect estimates from the different subsampled surveys; and (3) achieving improvements in the data quality and reporting rates in the supported self-administered procedures used with the subsamples. It also provides panel data and a complete picture of a household on a subset of the overall sample.

Key Assumptions

Design C makes several key assumptions about the collection of consumer expenditure data:

- All the key assumptions listed under Design A are present.

- Strong correlations exist for covariates measured in the base survey and later phases of data collection.

- Effective models involving covariates such as demographic characteristics can construct estimates using the different subsampled surveys.

- Collecting a complete picture of household expenses and income on a substantial component of the overall sample with modeling of

- smaller expenditure items from a different sample will be sufficient for economic and policy analysis.

- A one-month tablet-based reporting period for documenting ongoing purchases is plausible. This is an open research question.

Sample Design

Design C includes a base survey followed by surveys of more intensive and frequent measurements. The base survey would have a relatively large sample size, collecting information to use for stratification and modeling. From that base, two sets of independent samples would be drawn. Sampled units in the first component are asked to keep a supported journal for one month to proactively record detailed expenditures. Sampled units in the second component are contacted for quarterly recording of aggregate expenses for two quarters.

The Base Survey: The base sample is a large, address-based sample similar to the current CE Interview sample. This initial survey forms a stratification base for sampling later phases of more intensive data collection. Base survey data are also used in models, combining them with data from later phases to produce estimates. In order to keep the base sample “fresh,” it would be supplemented each quarter with new samples that would be interviewed. This allows base survey data collection to go on throughout the year, and the samples for more intensive data collection to be selected using an updated base.

Detailed Expenditure Component: Design C calls for selecting 12 independent samples (one for each month) from the base survey and asking households in those samples to keep a supported journal of expenditures for one month. The purpose of these surveys is to proactively collect detailed expenditure data in the same manner as described in Design A. These data would be used in national and regional estimates, with precision enhanced by modeling back to the base survey and combining with data collected from the household profile component.