Proposition 71 specified in considerable detail a distinctive governance structure for the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), including organization and management systems. As with other provisions of the proposition, these governance provisions could not be changed until the third year following adoption, and then only with the approval of 70 percent of each house of the legislature and the signature of the governor. Nonetheless, in 2010, Senate Bill (SB) 1064 made several amendments to Proposition 71, some of which pertained to these systems1 (see Appendix C for details of Proposition 71 and Appendix D for details of SB 1064). Because these systems can be modified either by legislation or by voter initiative, the committee takes a broad view of its charge to review them and offers recommendations for changes, even if these changes would require modifying current law.

This chapter begins with a brief overview of certain distinctive features of CIRM’s governance structure as articulated in Proposition 71 and a comparison of this structure with that of similar programs in other states. The chapter then turns to its principal focus—an assessment of the effectiveness of CIRM’s organization and management systems and recommendations for changes in those systems that might better serve CIRM’s mission going forward.

__________________

1Senate Bill (SB) 1064 left unchanged the existing membership composition of the Independent Citizens Oversight Committee.

ORGANIZATION OF CIRM’S GOVERNANANCE STRUCTURE

Proposition 71 established the 29-member Independent Citizens Oversight Committee (ICOC) as CIRM’s governing board. It set forth detailed provisions specifying qualifications for each seat on the ICOC, allocating power to certain University of California chancellors and particular state constitutional officers to fill seats in a way that ensured representation of specified stakeholders (CIRM, 2012a). The chancellors of the University of California, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco, were each assigned one seat to fill with an executive officer from the respective campus, with four additional executive officers of the University of California to be selected for ICOC membership by the governor, lieutenant governor, treasurer, and controller, for a total of nine ICOC members from the University of California system. The same four state constitutional officers were each assigned further seats on the ICOC to fill with executive officers of academic and research institutions that are not part of the University of California (four members), California-based life sciences companies (four members), and representatives of specified disease advocacy groups (eight members), while the speaker of the assembly and the president pro tempore of the Senate were each assigned to appoint representatives of additional disease advocacy groups, for a total of 10 disease advocacy representatives on the ICOC (CIRM, 2009a, 2012b). The only seats on the ICOC that were specifically to be filled by individuals without a direct stake in the activities of CIRM were the four seats for executive officers of California-based life sciences companies, who by law could not come from entities that were actively engaged in stem cell research or that had been awarded or applied for CIRM funding at the time of appointment. Members from the University of California campuses and advocacy groups serve 8-year terms, while other members serve 6-year terms (CIRM, 2012b).

Although as a formal matter, the ICOC members are authorized to elect their own chair and vice chair,2 Proposition 71 specifies stringent criteria for these positions, including that the chair and vice chair must be qualified for one of the appointments set aside for representatives of disease advocacy organizations. The chair and vice chair are both to be CIRM employees and may not concurrently be employed by or on leave from an institution that is a prospective recipient of a CIRM grant or loan, a provision that effectively disqualifies ICOC members from academic and research institutions

__________________

2“The Governor, the Lieutenant Governor, the Treasurer, and the Controller each nominate a candidate for Chair and a candidate for statutory Vice Chair. (Id., § 125290.20(a)(6).) The Board has the authority and responsibility to elect a Chair and a statutory Vice Chair from among the individuals nominated by the Governor, the Lieutenant Governor, the Treasurer, and the Controller” (CIRM, 2012b).

for these positions even if they otherwise meet the specified requirements (CIRM, 2012a).

Proposition 71 also calls for the creation of three working groups—a 19-member Scientific and Medical Accountability Standards Working Group (Standards Working Group), a 23-member Scientific and Medical Research Funding Working Group (Grants Working Group), and an 11-member Scientific and Medical Facilities Working Group—to provide guidance to the ICOC. Membership of each of these advisory bodies is set by law to include the ICOC chair, a specified number of ICOC members from the disease advocacy groups, and nonmembers who provide additional expertise and manpower (CIRM, 2012a).

The recommendations of the working groups to the ICOC have been important and influential, but the groups have no formal decision-making authority beyond offering recommendations. The Scientific and Medical Facilities Working Group, although important in the early stages when CIRM was financing the building of new facilities for stem cell research, is now inactive (CIRM, 2009b). The Standards Working Group continues to play a key role in setting the ethical standards for CIRM-sponsored programs (CIRM, 2009c). The Grants Working Group has played a large role in the review of grant applications (CIRM, 2009d), as discussed more fully in Chapter 4. In addition to the working groups, the bylaws of the ICOC allow for the establishment of subcommittees to facilitate its work.3

The generous size of the ICOC and its working groups stands in contrast to a parsimonious approach toward staffing the Institute itself.4 As originally passed, Proposition 71 set a cap of 50 on the number of CIRM employees, excluding members of the working groups. SB 1064 eliminated that cap, but retained a cap on administrative expenses of 6 percent of bond funding, including not more than 3 percent for research and research facility implementation costs and not more than 3 percent for general administration of the Institute, as well as a provision that allows the ICOC to determine the total number of authorized employees. The wording of SB 1064 reflects the original design set forth in Proposition 71, which relies heavily on the governing board and its working groups to perform tasks that in many research organizations are usually allocated to management-supervised staff.

A similar allocation is apparent in the way Proposition 71 divides responsibility for leadership of operations between the CIRM president, who serves as the Institute’s chief executive officer, and the board chair, who has significant management responsibilities for operations in addition

__________________

3Currently, there are subcommittees on governance, finance, legislative, intellectual property, industry, communications, science, and evaluation (CIRM, 2009a).

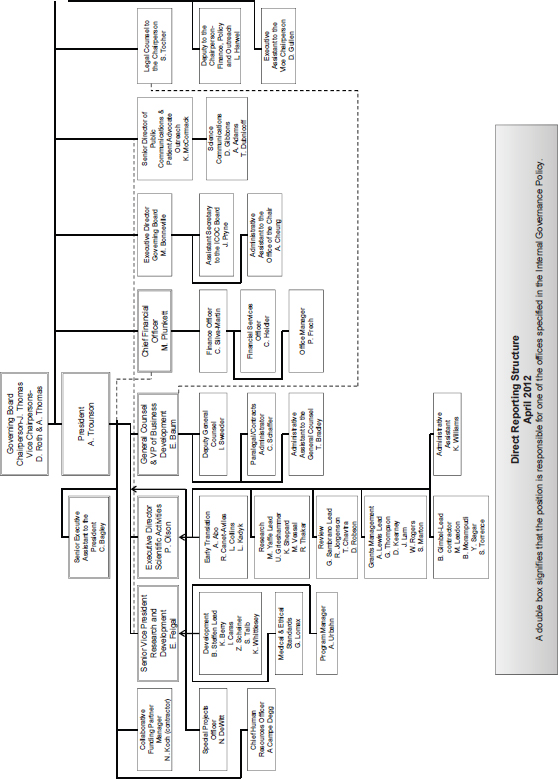

4See Annex 3-1 for figure depicting organizational structure of CIRM.

to managing the ICOC itself. In some cases, the allocation of responsibility for important management functions splits these responsibilities down the middle. For example, the chief financial officer reports to both the chair and the president, with responsibility for external financing resting with the chair and that for internal financial reporting and analysis with the president (CIRM, 2011a). Communications also are a joint responsibility, with the chair being responsible for public communications and the president for scientific communications (CIRM, 2011b).5 To some extent, this allocation follows from the original language of Proposition 71: the chair is directed “to manage and optimize the institute’s bond financing plans and funding cash flow plan” and “to interface with the California Legislature, the United States Congress, the California health care system, and the California public,” while specific directives for the president begin with the provision of staff support for the ICOC and working groups and then list responsibilities for internal management, budgeting, and compliance.6

These somewhat unique arrangements reflect, in part, the unique origins of CIRM that relied on sustaining a very broad and effective coalition of patient advocates, scientists, and leaders of important research institutions. Although the committee believes that the structure served the institute well in its first several years, there are reasons to consider some changes going forward.

GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE OF PROGRAMS COMPARABLE TO CIRM

The committee thought it would be helpful to compare CIRM’s governance structure with that of the similar state research initiatives discussed in Chapter 2. Connecticut, Maryland, New York, and Texas each have initiated programs to support science and technology with the goal of furthering economic development and the scientific enterprise in the state. Although the governance structure of each of these programs shares some key similarities with that of CIRM, such as the use of a board to provide guidance to staff managing the program on a day-to-day basis, there are differences in the structure and composition of these boards, the manner in which they provide oversight, and the extent to which they have management responsibilities. The programs also are integrated into state government in different ways and thus interact with existing agencies differently. One of the unusual aspects of CIRM is that it was created as a separate state

__________________

5In these two areas of joint responsibility, the chair and president are expected to collaborate in order “to ensure that CIRM speaks with one voice” (CIRM, 2011b, p. 4).

6California Stem Cell Research and Cures Initiative, Proposition 71 (2004) (codified at California Health and Safety Codes § 125291.10-125291.85), p. 4.

agency. Finally, with the exception of the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), the governing board of each of the other state programs has members with built-in conflicts of interest because they are from institutions that are current recipients of agency funds. A high-level comparison of the oversight boards of CIRM and the four comparable programs is shown in Table 3-1.

PRIOR ASSESSMENTS OF CIRM’S GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE

CIRM has been the subject of a number of thoughtful evaluations during the past 5 years. Its governance structure, its internal financial controls and compliance record, and its scientific program have been separately assessed by various review bodies, including an External Advisory Panel (EAP), initiated and selected by CIRM itself; the independent Little Hoover Commission, whose review was undertaken at the behest of California legislators; and, most recently, Moss-Adams, LLP, which performed an external audit required by SB 1064. These assessments have praised CIRM’s effectiveness in developing and managing its research portfolio and in meeting its most important responsibilities under Proposition 71 and as modified by SB 1064. They have also raised a number of consistent criticisms.

In 2008, Senators Sheila Kuehl and George Runner7 asked the Little Hoover Commission to evaluate and recommend ways to strengthen CIRM’s governance structure, as well as to recommend ways in which CIRM could improve accountability and reduce conflicts of interest. The Commission’s 2009 report found that CIRM had been successful in establishing California as a leader in stem cell science and credited the Institute with attracting $900 million in matching funds, as well as drawing scientists to California from elsewhere in the United States and abroad (LHC, 2009). The Commission also recommended a number of changes in CIRM’s governance structure to address conflict of interest issues and otherwise improve governance and accountability. CIRM rejected many of these recommendations as inconsistent with the dictates of Proposition 71 (CIRM, 2009e). The committee suggests that CIRM reconsider this position, because the committee believes many of the recommendations are sound and would enhance CIRM’s ability to accomplish its goals. As the passage of SB 1064 demonstrates, when CIRM and the California legislature work together in

__________________

7Senators Kuehl and Runner authored the proposed and subsequently vetoed California bill SB 1565, which would have enacted intellectual property policy provisions covering research funded by CIRM and would have asked the Little Hoover Commission to review CIRM’s governance. When the bill was vetoed, the senators wrote a letter directly to the Commission to request the study.

TABLE 3-1 Overview of Oversight Boards

| California | New York | Connecticut | Maryland | Texas | ||

| Board Name | Independent Citizens Oversight Committee (ICOC) | Empire State Stem Cell Boarda | Stem Cell Research Advisory Committee | Maryland Stem Cell Research Commission | Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Oversight | |

| Committee | ||||||

| Size | 29 | 13 | 17 | 15 | 11 | |

| Term Length | 6 or 8 years (maximum of two terms) | 3 years (maximum of two terms) | 4 years (maximum of two terms) | 2 years (maximum of three terms consecutive) | 6 years | |

| Chair | Elected by the ICOC following nominations by California constitutional officers | Commissioner of Health | Commissioner of the Department of Public Health | Elected from membership by board members | Elected from membership by board members | |

| Appointed by (no. of members) |

• Chancellors of University of California (UC) schools (5) • Governor (5) • Lt. governor (5) • Treasurer (5) • Controller (5) • Speaker of the Assembly (1) • President pro tempore of the Senate (1) |

• Governor (12) • Temporary president of the Senate (4) • Speaker of the Assembly (4) • Senate minority leader (2) • Assembly minority leader (2) |

• Governor (4) • President pro tempore of the Senate (2) • Speaker of the House (2) • Senate majority leader (2) • House majority leader (2) • Senate minority leader (2) • House minority leader (2) |

• Governor (4) • President of the Senate (2) • Speaker of the House (2) • University of Maryland (3) • Johns Hopkins University (3) |

• Governor (3) • Lt. governor (3) • Speaker of the House (3) |

|

| Ratio of Members at Recipient Institutions to Total Board Membersb | 14/28 | 4/9 | 3/12 | 7/15 | 0/11 | |

aThe Empire State Stem Cell Board consists of two committees: the funding committee and the ethics committee. Information is provided here for the entire board, except for the ratio of members at recipient institutions to board members, which includes only funding committee members for comparability with the other state programs.

bThe ratio of board members at recipient institutions to total board members is current as of August 2012. The total number of board members is less than the board size for some programs because of vacancies. SOURCES: California Program: http://www.cirm.ca.gov; New York Program: http://stemcell.ny.gov; Connecticut Program: http://www.ct.gov/dph/cwp/view.asp?a=3142&q=389702&dphNav_GID=1825; Maryland Program: http://www.mscrf.org; Texas Program: http://www.cprit.state.tx.us.

the interests of the state’s citizens and the field of regenerative medicine, they can enact useful modifications to Proposition 71.

In 2010, CIRM commissioned the EAP review to provide external and objective advice on its scientific strategy (discussed further in Chapter 4) and its associated policies and procedures. The report of this group of experts in stem cell research, ethics, and business states that “in a remarkably short period of time, CIRM has initiated an ambitious and comprehensive program.” The report congratulates the ICOC and CIRM staff for the “extraordinary and rapid start up of [CIRM] programs” (EAP, 2010, p. 3).

The 2012 audit by Moss-Adams examined CIRM’s functions, operations, management systems, policies, and procedures. The audit was required under SB 1064, which called for a performance audit every 3 years beginning with the 2010-2011 fiscal year. Overall, the report finds that CIRM is in full compliance with its stated policies. It characterizes CIRM staff as mission-driven, talented, dedicated professionals who are “committed to transparency and good stewardship of public funding” (Moss-Adams, LLP, 2012, p. 2).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee agrees with the largely positive findings of the previous evaluations summarized above concerning the achievements of CIRM. The committee recognizes that the Institute’s current governance structure, as designed by Proposition 71, may have been appropriate at the start of the endeavor and contributed to its early success. Proposition 71 was passed at a time when stem cell research faced considerable political opposition at the federal level, making it important to protect the Institute from potentially hostile political oversight. Moreover, when CIRM was starting up, it may have been expedient to meld operations and oversight. The initial structure, delegating expansive management roles to a large board of stakeholders and centralizing a great deal of authority in the chair position, provided the energy and expertise needed to get the organization up and running and to fund important foundational work as quickly as possible.

The committee also agrees with the observations of previous evaluations—especially the report of the Little Hoover Commission—concerning the need for improvements in CIRM’s governance structure as it moves beyond the startup phase. Now that CIRM is a more mature organization, it and the citizens of California would be better served by a modified governance structure. The Little Hoover Commission made a series of recommendations, some of which were echoed in the 2012 performance review by Moss-Adams, regarding more efficient and effective governance and administration.

This section provides the committee’s assessment of various elements of

CIRM’s current organization and management systems and makes a series of recommendations intended to strengthen CIRM.

Separate Operations from Oversight

In the current governance structure, oversight and operations are pervasively intertwined. Proposition 71 established a large board, relying on working groups that report directly to the board to perform operations that in many research organizations are the job of staff reporting to the president. Additionally, the strict composition requirements of the board as detailed in Proposition 71 create inherent conflicts of interest for most board members. With respect to conflicts of interest, the committee did not uncover or search for evidence of any inappropriate behavior by any board members. The point is that the board suffers from a wide range of perceived conflicts generated directly by the particular and unique governance requirements of Proposition 71.

The committee believes CIRM would benefit from a clear and appropriate separation of duties, with the board having primary responsibility for oversight and strategy and the staff for implementation through day-to-day operations. While management has made significant strides to more carefully define duties of senior staff (Trounson, 2012), by themselves, these new position descriptions do not deal with the challenge of allowing the ICOC to provide independent oversight of management. Without such separation of duties, CIRM and the California taxpayers, who will repay the public funds that CIRM is expending, are deprived of the benefits of objective oversight that an independent board can provide. The current structure of the ICOC impedes independent oversight because it relies on the ICOC to function as both overseer and executer. The current structure makes sense as a way of protecting one kind of independence—the independence of CIRM from political pressures and the shifts in public opinion. But it fails to protect another kind of independence—independent oversight over the actions of CIRM itself that the people of California are entitled to expect from the board of a public institution.

Interface Between the ICOC and Management

The board currently makes decisions that would more typically be handled by management and staff. For example, a key management responsibility such as grants selection is performed by the board’s Grants Working Group and subsequently modified by the board. The committee believes these allocations of roles and responsibilities should be revised—that the board should transfer management responsibilities to management so it

can provide truly independent oversight and evaluation of management, strategic planning, and broad direction for resource allocation.

While organizations such as the National Association of Corporate Directors provide guidance regarding the functions and benefits of an independent board, the committee is not aware of similar guidance for not for profit boards. However, the committee believes that the independence of the board is all the more important for a state agency supported by tax payers.

In the corporate governance setting, a typical concern is that excessive management control of the board may threaten the board’s independence (Investopedia, 2008), while in the case of CIRM, the greater concern may be that the board itself is performing management functions. Either way, however, the board is compromised in its ability to serve as an independent check on the actions of management.

Prior groups evaluating CIRM have also suggested that CIRM should separate the roles and responsibilities of the ICOC from those of staff, delegating some of its current functions to management as is consistent with good governance practice. The EAP report suggests that the role of the ICOC should be limited to strategy setting and oversight. It states

The CIRM Governing Board has had a very hands-on approach to CIRM in its first six years. This approach is appropriate for start-ups, especially one that is publicly funded and accountable such as CIRM. As CIRM transitions to Stage II, we believe this is an appropriate time for the Governing Board to examine its role and composition, mindful of the legal reporting, fiduciary and accountability requirements of the state of California. (EAP, 2010, p. 11)

Results of the 2011 survey of the board commissioned by the ICOC itself suggest that some board members agree with the above external assessments of the board’s performance and the appropriateness of its current management role. Fully 90 percent of the board members stated that the board was too involved in operations and administrative/management details (Remcho, Johansen & Purcell, LLP, 2011). The attorneys who were commissioned to carry out the survey provided their own recommendation for addressing this concern within the strictures of Proposition 71: they suggested that the board could use its discretion with regard to its statutory duties to shift functions to the staff. They offered two models: a partnership model in which the chair and vice chairs would carry out their duties in partnership with the president, or a delegation model in which the board could request that the chair and vice chairs delegate duties to staff to the extent permitted by law, with the board playing an oversight rather than an operational role. Yet while these suggestions may offer a short-term solution to the legal constraints that CIRM believes currently prevent it from

separating management and oversight functions, more effective adaptations need to be identified and implemented for the longer term.

Limiting the involvement of the board and its chair in day-to-day management might also make it easier for CIRM to attract and retain good senior management. There has been a high degree of turnover in the Institute’s senior management positions. Since 2006, CIRM has had five acting, interim, or official presidents, four chief scientific officers, four general counsels, and four financial/administrative officers (CIRM, 2011d). This high turnover rate, together with the creation and then elimination of the role of vice president of operations, may reflect unresolved management issues and a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities both within management ranks and between the board and management (Hayden, 2009; Miller, 2010). At her departure after just 14 months in 2009, chief scientific officer Marie Csete said she hoped her leaving would mark “a new start” for the agency. “I had tried everything I could to change what I think needed to change from the inside, and that was not going to happen,” she said. “I felt I would have more impact by stepping away and advising the leadership of the board on my way out about ways to revise the structure and management of the agency to make it more optimal” (Hayden, 2009, p. 17).

Interface Between the Chair and President

A related issue to the interface between the ICOC and management is the division of responsibilities between the chair and the president. As noted above, Proposition 71 assigns considerable responsibility for CIRM operations to the chair:

The chairperson’s primary responsibilities are to manage the ICOC agenda and work flow including all evaluations and approvals of scientific and medical working group grants, loans, facilities, and standards evaluations, and to supervise all annual reports and public accountability requirements; to manage and optimize the institute’s bond financing plans and funding cash flow plan; to interface with the California Legislature, the United States Congress, the California health care system, and the California public; to optimize all financial leverage opportunities for the institute; and to lead negotiations for intellectual property agreements, policies, and contract terms.8

By contrast, Proposition 71 charges the president with overseeing staff support for the ICOC and its working groups, in addition to serving as chief executive of the Institute and overseeing its staff:

__________________

8Proposition 71, 125290.45. ICOC Operations, 4.b.1.A.

The president’s primary responsibilities are to serve as the chief executive of the institute; to recruit the highest scientific and medical talent in the United States to serve the institute on its working groups; to serve the institute on its working groups; to direct ICOC staff and participate in the process of supporting all working group requirements to develop recommendations on grants, loans, facilities, and standards as well as to direct and support the ICOC process of evaluating and acting on those recommendations, the implementation of all decisions on these and general matters of the ICOC; to hire, direct, and manage the staff of the institute; to develop the budgets and cost control programs of the institute; to manage compliance with all rules and regulations on the ICOC, including the performance of all grant recipients; and to manage and execute all intellectual property agreements and any other contracts pertaining to the institute or research it funds.9

At present, the ICOC Internal Governance Policy, instead of delegating management tasks to the president, is moving in the opposite direction and adding management tasks to the chair’s responsibilities, including supervising the preparation of the annual financial plan. This tendency to add managerial roles to the ICOC also is reflected in the addition of another vice chair. CIRM’s willingness to embrace this innovation in the structure of the ICOC stands in notable contrast to its reliance on the strict terms of Proposition 71 in rejecting other proposed innovations. It also shows an inclination to enlarge rather than contract the role of the ICOC in day-today operations. In the committee’s judgment, the critical tasks performed by the vice chairs should be reassigned to management. In particular, the important tasks of government relations and corporate relations both should be carried out by staff reporting to the president rather than by the vice chairs of the board.

CIRM’s Internal Governance Policy also calls for the president and chair to jointly recommend an organization chart to the Governance Subcommittee, and assigns to the chair employment and compensation authority for staff in the Office of the Chair. In addition, the policy delegates responsibility for public communication to the chair and responsibility for scientific communication to the president, with a director of public communications reporting to the chair (CIRM, 2011a,b,c). This organizational structure adds further day-to-day operational responsibilities to the Office of the Chair, which the committee believes is inconsistent with good governance practices. Evidence suggests that the trend toward blurring oversight and operations is continuing with the newly created position of chief financial officer reporting jointly to the chair and the president (CIRM, 2012c). Certain roles and functions that the committee feels should be the

__________________

9Proposition 71, 125290.45. ICOC Operations, 4.b.1.B.

responsibility of the president currently are handled, in whole or in part, by the chair and the ICOC. One-quarter or 12 of 53 of the staff report to the chair, while Proposition 71 states that one of the president’s responsibilities is to “direct ICOC staff” and “to hire, direct, and manage the staff of the institute.”10 The committee believes good governance requires that the board delegate more authority and responsibility for day-to-day affairs to the president and senior management.

As noted earlier, the committee’s concerns with respect to the CIRM governance structure have been voiced previously by others. The Little Hoover Commission called for CIRM and the Legislature to eliminate overlapping authority between the chair and president and to improve the clarity and accountability of each. The Commission stated that “the board chair position, as structured, conflates day-to-day management with the independent oversight that the board is supposed to provide, straddling the roles of accountability and operations” (LHC, 2009, p. iii). It stated further that

To strengthen lines of communication and provide clear direction for the agency, the co-CEO management approach at CIRM should end, with the agency president placed in charge of all operations and the chair fulfilling only oversight duties, external affairs and board administration. The administrative limits set in Proposition 71 require a careful allocation of staffing and resources: the current overlapping roles of the president and the board chair complicate this effort, creating multiple reporting channels and functional redundancy. (LHC, 2009, p. iv)

This recommendation was echoed by the EAP, which called for clarity in roles and responsibilities between these two positions, particularly with regard to strategic direction, policies, international partnerships, funding decisions, public communications, and oversight. EAP member Alan Bernstein reported to the committee that:

In most organizations, the role of the Board is to deal with governance issues, including approving the vision, mission and strategic plan, oversee broad directions, policies, integrity, etc and to recruit the president/CEO. It is typically the president’s/CEO’s role to oversee the management of the organization, guide the board’s strategic discussions, etc. These roles can frequently become somewhat blurred during the start-up phase of an organization. As an organization starts to mature, it is important for the Board to step back, allowing the CEO and his/her executive to assume the roles and functions normally associated with management. Although we had not been asked to comment directly on this issue, our sense was that CIRM was evolving from its initial start-up phase into phase 2 and hence it would be important and timely for the Board and senior management

__________________

10California Stem Cell Research and Cures Initiative, Proposition 71 (2004) (codified at California Health and Safety Codes § 125291.10-125291.85).

to clarify roles and responsibilities between the Board and board chair and the president and senior management. (Bernstein, 2012)

While CIRM has clarified and defined roles, it has not, in the committee’s judgment, allocated responsibilities in the most effective manner. The key issue from the committee’s perspective is not only clarification of roles, but also allocation of responsibilities between the board and CIRM management in a way that best serves the interests of the Institute, California, and the field of regenerative medicine, consistent with sound governance practices regarding separation of duties and oversight.

The committee recommends that the ICOC diminish its involvement in day-to-day governance by delegating to the president and staff the operational tasks that Proposition 71 assigns to the chair. The committee believes problems with the current allocation of responsibilities between the chair and the president are not limited to a lack of clarity. The committee agrees with the Little Hoover Commission and the EAP that the current governance structure gives the board and chair too much involvement in day-to-day operations to the detriment of their ability to provide independent oversight.

Recommendation 3-1.11Separate Operations from Oversight. The board should focus on strategic planning, oversee financial performance and legal compliance, assess the performance of the president and the board, and develop a plan for transitioning CIRM to sustainability. The board should oversee senior management but should not be involved in day-to-day management. The chair and the board should delegate day-to-day management responsibilities to the president. Each of the three working groups should report to management rather than to the ICOC.

Change the Composition and Structure of the Board and Working Groups

Board Composition

The committee believes the predominance of direct stakeholders—defined as individuals with a direct stake in the processes and outcomes of CIRM’s activities that arises outside of their service to the Institute—in the composition of the ICOC compromises its independence in another manner beyond the entanglement of oversight and operations. Board members with personal and professional interests in the activities of CIRM that go beyond the interests of the general public undoubtedly bring considerable energy

__________________

11CIRM may need to work with the state legislature in order to fully implement this recommendation.

and commitment to the tasks before them, but they may also introduce bias into the board’s decisions that compromises its stewardship over CIRM as a public institution. In its report, the Little Hoover Commission recommended that the California Legislature amend the Health and Safety Code to reduce the board size, shorten terms of board members, and restructure membership to add independent voices in order to increase efficiency and transparency.

In the committee’s opinion the board’s composition should be modified to include a majority of members who are “independent” in the sense of having no direct personal or professional interest that might compete or conflict with the interests of CIRM and the people of California in ways that bias their decisions. The size of the board should be maintained or decreased in this process. The committee did not find empirical data indicating the optimal size for an organization’s board. However, in the committee’s opinion the size of the board should not be enlarged in the process of increasing the number of independent members. The board should include representatives of the diverse constituencies with interests in stem cell research, but no institution or organization should be guaranteed a seat on the board.

To bring fresh perspectives from diverse representatives while maintaining continuity, the ICOC should phase in a plan to stagger members’ terms. Doing so would allow broader representation over time from a wider variety of stakeholders while providing both continuity and new perspectives.

Working Groups

As noted previously, CIRM has relied heavily on the three working groups specifically outlined and charged in Proposition 71 to perform a series of critical tasks. These working groups have provided critical advice to the ICOC in such areas as facilities; ethics and standards; and, perhaps most important, assistance to CIRM in building its scientific programs. They have unquestionably played an important role in the Institute’s evolution. The high-quality input they provide will continue to be critical in the coming years. At present, these working groups report directly to the chair. However, the committee believes they would more properly report to CIRM’s senior management, thus reserving the ICOC to exercise its high-level and independent strategic oversight responsibilities. As discussed further in Chapter 4, some decisions made by the Grants Working Group are overturned by the ICOC. There has been an increase in the number of extraordinary petitions (applicants’ written petitions to the ICOC regarding the application after review by the Grants Working Group). As of October 2012, 32 percent of petitions were successful. This increase in successful

appeals undermines the credibility and independent work of the Grants Working Group.

Therefore, it is important that the chair and other ICOC members not serve on the working groups. As board members are replaced, the working groups should not lose the fundamental and critical perspective of disease advocates. Instead, the disease advocate board members should be replaced on the working groups with an equal number of disease advocates who are not board members. In this way, an even broader group of patient advocates would have a role in the activities of the Institute and the ICOC will make strategic decisions. Working groups should report to the same management team, not to members of senior management, so that continuity and coherence are not lost.

Recommendation 3-2.12Change the Composition and Structure of the Board and Working Groups. CIRM should put systems in place to restructure the board to have a majority of independent members, without increasing the size of the board. It should include representatives of the diverse constituencies with interests in stem cell research, but no institution or organization should be guaranteed a seat on the board. Consideration should be given to adding members from the business community. The terms of board members should be staggered to balance fresh perspectives with continuity.

The chair and other ICOC members should be prohibited from serving on the working groups. During the reconstitution of the working groups, the current level of representation of disease advocates should be maintained, such board members being replaced with other disease advocates who are not board members.

Revise Conflict of Interest Definitions and Processes

The ICOC is overwhelmingly composed of representatives of (1) organizations that receive substantial CIRM funding and (2) disease advocacy communities. This composition raises questions about whether decisions delegated to the board—particularly decisions about the allocation of funds—will be made in the best interests of the public or will be unduly influenced by the special interests of board members and the institutions they represent. Such conflicts, real or perceived, are inevitable given the provisions of Proposition 71 and were not addressed by SB 1064. Proposition 71 attempts to set aside the concern about conflict of interest through

__________________

12CIRM may need to work with the state legislature in order to fully implement this recommendation.

statements that no such conflict exists. For example, Proposition 71 states that service on the ICOC “shall not, by itself, be deemed to be inconsistent, incompatible, in conflict with, or inimical to the duties of the ICOC member as a member of the faculty or administration of any system of the University of California” and that service on the ICOC “by a representative or employee of a disease advocacy organization, a nonprofit academic and research institution, or a life science commercial entity shall not be deemed to be inconsistent, incompatible, in conflict with, or inimical to the duties of the ICOC member as a representative or employee of that organization, institution, or entity.”13 Although this language may be adequate to protect ICOC members from legal liability, it has not prevented persistent accusations regarding conflicts of interest (LHC, 2009). According to the Little Hoover Commission report, “Even though a board with interested parties can operate within legal bounds, the Commission is concerned that the lack of disinterested members on the ICOC weakens the board’s ability to make sound decision [sic], and limits the likelihood that there will be substantial debate and dissent among board members about key funding and policy decisions. Such a dynamic also erodes confidence that the board is capable of making broader strategic decisions that go beyond awarding research dollars” (LHC, 2009, p. 16).

The committee received divergent responses to questions about conflict of interest in its questionnaire to ICOC members.14 Although a majority of respondents stated that personal interests did not play a role in their work on the ICOC, some responses were more equivocal. One respondent replied that it was “hard to tell” given that “so many decisions take place off camera in secret meetings,” while another acknowledged that “ICOC members are human, and of course their decisions are influenced by personal beliefs and interests…. Board members also have a sincere dedication to represent their constituents, for example patients who suffer from diseases or disorders that might benefit from stem cell therapies.” One member suggested that the different biases of stakeholders on the board “can be seen as positive” and that “although self-interest cannot be completely eliminated, the separate range of interests of the different board members provides a good measure of protection from runaway, and risky, decisions” (IOM, 2012). At a minimum, these divergent responses suggest that the ICOC members do not have a shared understanding of conflict of interest and its role in their deliberations, indicating a need to address the issue through regulations and training.

Properly understood, conflict of interest is not misconduct, but bias

__________________

13California Stem Cell Research and Cures Initiative, Proposition 71 (2004) (codified at California Health and Safety Codes § 125291.10-125291.85).

14See Appendix B for a summary of questionnaire responses.

that skews the judgment of a board member in favor of interests that may be different from or narrower than the broader interests of the institution. Inherent conflicts arise from the interests of board members as employees of grantees and as representatives of disease advocacy organizations. Board members who are especially concerned with the interests of particular institutions or disease areas may not recognize when those interests depart from the best interests of the people of California. Whatever the behavior of the board, conflicts of interest, real or perceived, threaten to distort and to undermine respect for its decisions.

Although the committee did not uncover or search for any evidence that conflicts of interest have overtly influenced decision making by ICOC members, studies from psychology and behavioral economics show that conflict of interest leads to unconscious and unintentional “self-serving bias” and to a “bias blind spot” that prevents recognition of one’s own bias (IOM, 2009, pp. 358-374). Bias distorts the evaluation of evidence and the assessment of what is fair (IOM, 2009, pp. 258, 364). There recently has been an increased focus on the importance of minimizing bias and conflict of interest in science fields (Broccolo and Geetter, 2009; Ehringhaus et al., 2008; IOM, 2009; Vogeli et al., 2009). A 2009 report from the Institute of Medicine concludes that “the goals of conflict of interest policies in medicine are primarily to protect the integrity of professional judgment and to preserve public trust rather than to try to remediate bias or mistrust after they occur” (IOM, 2009, p. 5).

CIRM should acknowledge and manage the full range of conflicts that are inherent in the current composition of the ICOC. California law focuses primarily on financial conflicts of interest, but the committee believes that personal conflicts of interest arising from one’s own or a family member’s affliction with a particular disease or advocacy on behalf of a disease area also can create bias for board members. In this regard, almost all members of the ICOC are interested parties with a personal or financial stake in the allocation of CIRM funding that goes beyond their interests as representatives of the people of California. These members include representatives of institutions that seek CIRM funding and representatives of disease advocacy groups with missions that might be affected by the allocation of CIRM funding. Although this conflicted board composition is specified and sanctioned by the terms of Proposition 71, it raises questions about bias that could distort the decisions made by ICOC members in their role as stewards of the interests of the taxpayers who will have to repay the borrowed funds that CIRM is spending. Over the years, reports from stakeholders and consumer advocates have criticized CIRM’s lack of transparency, particularly as it relates to the process of awarding of research grants (LHC,

2009; Simpson, 2012). The committee believes that by addressing conflict of interest, issues of transparency will be alleviated.

The primary mechanism in CIRM’s policies for managing conflict of interest is recusal from participating in deliberations and voting on matters that affect the financial interests of a conflicted individual (CIRM, 2006). Voting records from ICOC meetings show many members recusing themselves from participation in particular decisions. CIRM has no policies to manage nonfinancial conflicts, such as those arising from affiliation with a disease advocacy group or an individual’s interest in a specific disease. Nonfinancial conflicts may call for more sensitive and flexible tools than CIRM currently uses to manage financial conflicts of interest. Although they may be powerful sources of bias, nonfinancial conflicts may have important privacy implications, especially when they touch on matters of personal health. Moreover, the same interests that give rise to such conflicts may give conflicted individuals valuable insights that could be lost from deliberations if those individuals were excluded from participation. These considerations complicate the task of managing nonfinancial conflicts of interest, but they do not justifying ignoring these conflicts. The committee urges CIRM to consider these competing considerations fully in revisiting its conflict of interest policies. Even for purely financial conflicts, recusal becomes a less satisfactory tool as the number of conflicts increases.

The presence of conflicts for individual board members would be less cause for concern if the board had more nonconflicted members. CIRM should address real and apparent conflicts of interest, including and beyond financial interests, built into its governance structure regardless of whether these conflicts have in theory been waived by the voters or excused under California law. EAP member Alan Bernstein stated in an interview with the committee: “Regarding the composition of CIRM’s governing board, the panel thought there should be a better balance between individuals representing recipient institutions and individuals who represent the broader California public” (Bernstein, 2012). The Little Hoover Commission in its report indicated that “the board lacks truly independent voices to balance out those of interested board members. The founding board members’ terms are too long and are not conducive to adding fresh perspectives about the agency’s future given the rapid advancement of stem cell science” (LHC, 2009, p. iv). Other state programs (described above) have addressed conflicts of interest among board members by adding out-of-state members (Connecticut) or removing university leadership from the primary oversight board and creating a university advisory committee (Texas).

Recommendation 3-3.15Revise Conflict of Interest Definitions and Policies. CIRM should revise its definitions of conflict of interest to recognize conflicts arising from nonfinancial interests, such as the potential for conflict arising from an individual’s interest in a specific disease, and should reassess its policies for managing conflict of interest in light of this broader definition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the governance structure for CIRM is unusual in important respects that the committee believes could diminish its effectiveness going forward. The legislatively mandated composition of the ICOC was structured to tackle a challenging mission at a challenging time. However, in the committee’s judgment both CIRM and the citizens of California would be better served going forward with a modified governance and administrative structure as outlined above. The ICOC has had more extensive operational responsibilities than is typical for a governing board, and the chair and vice chairs have duties that are more typically performed by a CEO. The working groups that report to the ICOC and that include ICOC members perform functions (such as peer review of grant proposals) that other institutions more commonly delegate to independent advisors reporting to scientific staff. The size of the ICOC, augmented by the non-ICOC members of the working groups, is large compared with the size of the CIRM staff.

The membership of the ICOC is skewed toward representatives of institutions that have a direct stake in how CIRM allocates its funding. Although this profile of the ICOC was understandably designed to include representatives from a broad range of those most concerned and most knowledgeable regarding the future of regenerative medicine, they also were the constituencies expected to benefit most directly and immediately from CIRM’s grants. These features make a certain amount of sense as a reflection of CIRM’s origins and the challenges it faced in its early years. But each feature has drawn criticism, raising questions about whether at this stage the original governance structure best serves the interests of CIRM and of the California taxpayers who will repay the funds that CIRM is spending. The current structure has created challenges for CIRM which distract from the Institute achieving its core mission. For example, high staff turnover, increasing number of extraordinary petitions (discussed further in Chapter 4), and persistent criticisms and perceptions that conflicts of interest and lack of independence of board members influence grant funding.

Many of these problematic features of CIRM’s structure are prescribed

__________________

15CIRM may need to work with the state legislature in order to fully implement this recommendation.

by California law and can be changed only by the California Legislature or by another voter initiative. In assessing CIRM’s current governance structure and proposals for reform, the committee did not limit considerations and recommendations to the boundaries imposed by Proposition 71. Instead, the committee worked to develop recommendations that would best serve CIRM and the California taxpayers from this point forward.

The committee believes that CIRM and the California taxpayers would be better served by a governance structure in which the role of the ICOC would remain focused on broad oversight and strategic planning rather than involvement in day-to-day management issues. The level of ICOC involvement in peer review and grant funding is particularly inappropriate given the stakeholder composition of the board. The ICOC should include more independent members who have no financial or other interests, either as individuals, as employees or officers of grantee institutions, or as representatives of disease advocacy organizations, in the work of CIRM that are distinct from the broader interests of the taxpayers and that might influence their judgment.

An important theme of the committee’s governance recommendations is for CIRM to transition from the governance structure initially outlined in Proposition 71 to one the committee believes would better serve the interests of the citizens of California and the field of regenerative medicine. The committee fully appreciates that even in the best of circumstances, such a transition, if done thoughtfully, can take place only over time and that there may be challenges and resistance to any proposed changes. Moreover, the committee is aware that its recommendations regarding governance come at a time when CIRM may well be faced with even more pressing challenges resulting from the expiration of Proposition 71 funding and/or dynamic changes in the field of regenerative medicine. Nevertheless, issues of governance are critical for sustaining trust and should be given careful consideration.

Bernstein, A. 2012.*Summary of conversation with member of the External Advisory Panel. Committee on a Review of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) Phone Interview with Alan Bernstein, December 20, 2011, Washington, DC.

Broccolo, B. M., and J. S. Geetter. 2008. Today’s conflict of interest compliance challenge: How do we balance the commitment to integrity with the demand for innovation? Journal of Health and Life Sciences Law 1(4):1, 3-65.

CIRM (California Institute for Regenerative Medicine). 2006. Adopted CIRM stem cell grant regulations: Chapter 1. Conflicts of interest. http://www.cirm.ca.gov/Regulations#conflicts (accessed August 30, 2012).

CIRM. 2009a. CIRM Governing Board: Independent Citizens Oversight Committee (ICOC). http://www.cirm.ca.gov/GoverningBoard (accessed August 29, 2012).

CIRM. 2009b. About the Facilities Working Group. http://www.cirm.ca.gov/WorkingGroup_Facilities (accessed August 27, 2012).

CIRM. 2009c. About the Standards Working Group. http://www.cirm.ca.gov/WorkingGroup_Standards (accessed August 27, 2012).

CIRM. 2009d. About the Grants Working Group. http://www.cirm.ca.gov/WorkingGroup_GrantsReview (accessed August 27, 2012).

CIRM. 2009e. CIRM’s response to Little Hoover Commission report on CIRM. http://www.cirm.ca.gov/files/meetings/pdf/2009/081909_item_7A.pdf (accessed August 16, 2012).

CIRM. 2011a.*President position description. CIRM’s response to IOM’s data request: Documentation of roles and responsibilities for senior leadership positions, both ICOC and CIRM (dated December 13, 2011).

CIRM. 2011b. Internal governance policy: Exhibit C (approved by the board on May 4, 2011): Reorganization proposal introduction. http://www.cirm.ca.gov/files/PDFs/Administrative/Internal_governance.pdf (accessed August 15, 2012).

CIRM. 2011c.*Duties of the chairperson of governing board of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. CIRM’s response to IOM’s data request: Documentation of roles and responsibilities for senior leadership positions, both ICOC and CIRM (dated December 13, 2011).

CIRM. 2011d.*Governance & management leadership tenure turnover statistics. CIRM’s response to IOM’s data requests: Turnover statistics for key leadership positions (dated December 8, 2011).

CIRM. 2012a. ICOC bylaws. http://www.cirm.ca.gov/files/PDFs/ICOC/ICOC_Bylaws_05-24-12.PDF (accessed August 22, 2012).

CIRM. 2012b.*ICOC nomination selection process. CIRM’s response to IOM’s data request: Description of the selection and nomination process for ICOC membership (dated January 9, 2012).

CIRM. 2012c.*California Institute for Regenerative Medicine duty statement: Chief financial officer. CIRM’s response to IOM’s data request: Documentation of roles and responsibilities for senior leadership positions, both ICOC and CIRM (dated March 27, 2012).

EAP (External Advisory Panel). 2010. Report of the External Advisory Panel. http://www.cirm.ca.gov/files/PDFs/Administrative/CIRM-EAP_Report.pdf (accessed July 2, 2012).

Ehringhaus, S. H., J. S. Weissman, J. L. Sears, S. D. Goold, S. Feibelmann, and E. G. Campbell. 2008. Responses of medical schools to institutional conflicts of interest. JAMA 299(6): 665-671.

Hayden, E. C. 2009. Chief scientist quits California stem-cell agency. http://www.nature.com/news/2009/090630/pdf/460017a.pdf (accessed August 16, 2012).

Investopedia. 2008. Evaluating the board of directors. http://www.investopedia.com/articles/analyst/03/111903.asp/#axzz23j1fnhAI (accessed August 16, 2012).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012.*Summary: Questionnaire for Members of the ICOC. Institute of Medicine Committee on a Review of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine online questionnaire launched on February 6, 2012.

LHC (Little Hoover Commission). 2009. Stem cell research: Strengthening governance to further the voters’ mandate. http://www.lhc.ca.gov/studies/198/report198.html (accessed July 2, 2012).

Miller, G. 2010. CIRM: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Science 330(6012):1742-1743.

Moss-Adams, LLP. 2012. California Institute for Regenerative Medicine FY 2010-2011 performance audit. http://cirm.ca.gov/files/meetings/pdf/2012/052412_item_6.pdf (accessed July 13, 2012).

Remcho, Johansen & Purcell, LLP. 2011.*Governance & management memo re ICOC board survey exhibits. CIRM’s response to IOM’s data response: Information that can be shared about the 2011 ICOC conducted survey of board members to assess their current view of the role of the chairman and the overall performance of the board as a whole (dated January 28, 2012).

Simpson, J. M. 2012.* Presentation at the 3rd IOM meeting of Committee on a Review of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM). April 10, Irvine, CA.

Trounson, A. 2012.*CIRM’s new strategic direction in basic and translational science. Presentation at the 2nd IOM meeting of Committee on a Review of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), January 24, San Francisco, CA.

Vogeli, C., G. Koski, and E. G. Campbell (2009). Policies and management of conflicts of interest within medical research institutional review boards: Results of a national study. Academic Medicine 84(4):488-494.

References with an asterisk (*) are public access files. To access those documents, please contact The National Academies’ Public Access Records Office at (202)334-3543 or paro@nas.edu.