2

Logistics, Supply, and Demand

This chapter describes issues related to logistics, supply, and demand in the MDR TB SLD supply chain discussed at the workshop. The first section provides an overview of issues revolving around national- and international-level QA regulation of SLDs. The next section focuses on the importance of improved demand-forecasting methodology and improved information management systems in strengthening the SLD supply chain. The final section explores issues concerning national- and international-level drug shortages.

The function of QA for pharmaceuticals is to help guarantee that patients receive medicines that are safe, effective, and of acceptable quality. Technical as well as managerial activities (i.e., staff training and supervision) are included in comprehensive QA programs and span the entire supply chain process (MSH, 2011). During the workshop, speakers and participants discussed the definitions of “quality” with respect to SLDs, examined the benefits and limitations of existing SLD regulatory processes including WHO PQ, and discussed potential applications and lessons to be learned from other programs. This section first describes the existing international regulatory pathway for SLDs in the donor-funded market and then provides an overview of issues with respect to the national regulation of SLD. The section then summarizes the country-specific perspectives of India’s QA structure and Brazil’s model of a national QA program. Last,

the section examines the “vicious circle” of SLD supply and the effect of the limited supply of QA API on the structure of the SLD market.

International- and National-Level QA Regulation1

WHO Prequalification of Medicines Program

Lisa Hedman, WHO, explained that the WHO PQP serves as an international standard for stringent QA regulation of TB and MDR TB drugs. WHO PQ is a voluntary mechanism that does not supervene on an NRA’s decisions. Hedman noted that the WHO PQP can perform the function of an SRA proxy for manufacturers in countries without a SRA.2 Though WHO PQ does not provide automatic market access in individual countries, the PQ designation is a procurement requirement for many donorfunded procurements.

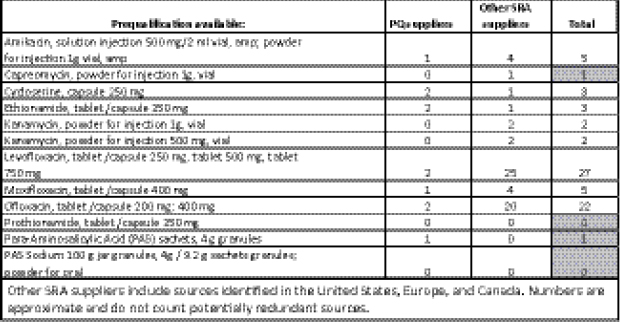

There are currently 12 formulations on the WHO list of PQ SLDs for MDR TB, from only 3 manufacturers (Figure 2-1).3 The small supplier pool for PQ SLDs exposes the global supply chain for MDR TB drugs to a significant risk of drug stock-outs should a single supplier stop production.

The essential medicines list has a policy-based function, whereas the WHO PQ list has a regulatory function. WHO PQ is renewed every 2 years and is intended as a model list to guide countries in the procurement of SLDs. The next review of first- and second-line anti-TB drugs will be carried out in March 2013, which, Hedman said, could provide an opportunity to renew outreach to countries and identify potential ways to “consolidate around logical and rational use of medicine.”

Scarcity of Data Linking QA and Treatment Outcomes

Hedman expressed her concern that although procurement of non-QA (i.e., not quality-assured by a recognized SRA) MDR TB products might secure better prices and provide wider coverage, it is not worth the risk of a trade-off in quality and efficacy. In a study carried out by WHO that tested PQ and non-PQ medicines for API and dissolution, an average of 10 percent of non-PQ products failed due to non-extreme deviations and

___________________

1 This subsection is based on the presentation by Lisa Hedman, Project Manager, WHO.

2 Hedman added that there are certain situations in which WHO requires PQ for a product that has already been approved by an SRA. This is because some countries use WHO PQ status as a “fast track” into their own approval systems. In such cases the PQ process usually has a fast turnaround time, she noted.

3 Of those 12, 4 have ≤1 SRA sources, and 6 have 2 or fewer.

FIGURE 2-1 WHO PQ second-line medicines as of the July 2012, IOM workshop.

NOTE: PQ, prequalified; SRA, stringent regulatory authority.

SOURCE: Hedman, 2012. Presentation at IOM workshop on Developing and Strengthening the Global Supply Chain for Second-Line Drugs for Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis.

1 percent failed due to extreme deviations.4 Hedman suggested that the general scarcity of data linking patient outcomes to QA status of a particular product has inhibited the ability to derive accurate conclusions about the true risk of treatment with non-QA drugs or substandard drugs.5 She therefore noted that there is a need to mine in-country primary data from MDR TB programs to inform the market and guide SCM. Joël Keravec, Brazil Country Program Director, MSH, commented that it is particularly difficult to link SLDs with treatment outcomes because MDR TB treatment regimens comprise multiple drugs and it is not possible to isolate the impact of one drug from another. A similar problem arises because patients are treated with drugs coming from different batches throughout the course of their lengthy treatment.

___________________

4 WHO Survey of Quality of Anti-TB Medicines in Selected Newly Independent States of the Former Soviet Union; none of the samples were assumed to be counterfeit. Extreme deviation was defined as the content of API deviating by more than 20 percent from the declared content and/or the average dissolution of tested units lower than 25 percent below pharmacopoeia Q value.

5 It would be unethical to systematically compare, or randomize in the context of a study, patients using substandard versus QA drugs.

Hedman described the TB environment as “fairly high-risk” with respect to the impact of shortfalls in quality, citing factors such as disease severity, challenges in patient follow-up, length of treatment, and the multiple drug regimens of MDR TB treatment as compounding the opportunities for drug failures. Few high-burden countries currently have (or are close to having) the capacity for pharmacovigilance, that is, the capacity to “monitor the quality of the medicines being made or imported,” an important component of stringent regulation.

Andreas Seiter, Senior Health Specialist, Pharmaceuticals, Health, Nutrition, and Population, World Bank, suggested that a key barrier to QA in pharmaceutical procurements is that existing and established QA processes are not enforced. He cited the example of quality tests in pre- and post-shipment inspection and testing that are required in the contract but are not carried out.

Christophe Perrin, QA Pharmacist, The Union, remarked that double standards in the manufacture of SLDs exist as a result of variability in the stringency of regulatory authorities and in producers’ commitments to quality. He cited anecdotal evidence that TB drug producers “are playing with some of the standards of what is inside a tablet” by using inadequately QA API for their FPPs. Andrew Gray, University of KwaZulu-Natal, expressed similar concern that some manufacturers, particularly large firms, might have WHO PQ status and adhere to stringent quality standards in only one of multiple plants that are producing the same drug.

National-Level QA

Noting that no international mechanism can “police” for QA if countries do not take ownership of the process, Keravec said the responsibility for QA should be transferred to countries. Countries should be supported to establish more stringent QA policies and procedures along with a mechanism for reporting problems that are detected, he added. Indeed, a strong in-country QA process should be able to detect production problems, including those of WHO PQ products when they arise. David Ripin, Executive Vice President, Access Programs, and Chief Scientific Officer, CHAI, agreed that moving countries toward self-regulation of products is important, and an important component of that ownership is agreement on bioequivalence for global products. Not all countries require bioequivalence as part of their QA programs, which might contribute to fragmentation of the market among drugs manufactured to satisfy different definitions of quality. Ripin expressed concern that many smaller countries need to rely on a common standard of quality, and that as countries move toward their

own levels of quality there needs to be “some mechanism for the smaller countries who aren’t going to be able to reach that critical mass on their own even if they can define quality in a robust manner.”

Participants discussed that some countries with non-donor-funded MDR TB programs opt not to procure PQ drugs. Meg O’Brien, Director, Global Access to Pain Relief Initiative, American Cancer Society, cited the need to determine those governments’ rationale for choosing non-PQ suppliers. She speculated that if governments had access to better data about the quality difference between PQ and non-PQ drugs, then their procurement practices might change. Peter Cegielski, CDC, noted that in practical terms, most countries favor domestic manufacturers whenever possible. Norbert Ndjeka, MDR TB Director, Department of Health, South Africa, noted that South Africa’s primary objective is better-quality drugs. He said that because the NTP does not have in-house technical expertise, it outsources QA to laboratories, academics, and experts. These advisory bodies determine the type and quality of drugs to be purchased by the government and also liaise with procurement agents. Thus QA in South Africa is largely dependent on separate, nongovernmental entities that advise the NTP.

Seiter suggested that emphasizing the commercial aspect—that it is easier to export products that adhere to a global quality standard—could serve as an incentive to national governments. Nina Schwalbe, Managing Director, Policy and Performance, GAVI Alliance (“GAVI”), remarked that a similar strategy was used by GAVI in India to address vaccine QA.

Cegielski suggested developing a system of regulatory reciprocity, in which one country accepts the regulatory processes and decision making of another, such that countries without SRA could accept approval from countries that do have stringent standards. Vincent Ahonkhai, BMGF, pointed out, though, that countries have a “statutory responsibility to regulate the product that circulates within their borders” and also that the reviews conducted by SRAs in other countries might not take into account factors specific to other countries, such as their health systems, environments, coincident diseases, and so on. Hedman remarked that regulatory reciprocity between countries does not exist anywhere except in the European Union via the EMA. In contrast to regulatory reciprocity, regulatory harmonization seeks to standardize methodologies, reduce the regulatory burden, and minimize delays.

Seiter explained that in the absence of stringent regulatory oversight, the buyer needs to ensure quality of the drugs procured. Usually a procurement agent is involved, and this agent has an in-house QC and QA system. A working group, under the leadership of WHO and participation of most relevant international funding and procurement agencies, has developed a tool for a standardized assessment of procurement agencies. This tool is based on WHO’s Model Quality Assurance System for procurement agencies

and allows for the first-time benchmarking of procurement agents and making their otherwise proprietary quality systems comparable. The tool is currently being tested.

Hedman commented that although it is important to foster long-term initiatives of national QA regulation such as those discussed here, in the short term there is an “immediate need to make sure that we reduce the risk of non-QA drugs that are going into high-burden countries.”

QA Regulation in India

As described in Chapter 1 (Box 1-4), the World Bank provides loans to the Indian government to cofinance its NTP, with the objective of building and strengthening India’s overall health system. According to Seiter, part of that system strengthening, particularly with respect to the NTP, should also include development of India’s own voluntary stringent regulatory pathway. This would enable the development of a recognized “seal of approval,” both for the purpose of exporting SLDs to other countries and to allow domestic procurement financed by external donors. At present, the Indian government employs a procurement agent, with an independent QA process in place, to procure SLDs directly from manufacturers. Seiter reported that it would cost the government three times as much to purchase a PQ product from the same company.

Brazil’s National QA Model

Brazil’s model for QA and management of SLDs can be characterized as a “rationally established environment,” whereby the NTP is responsible for maintaining and assuring the quality of its TB drugs. The majority of SLDs are produced in-country in the public and private sectors. Keravec explained how, in Brazil, product quality is assured through a national regulatory system of registration, documentation, monitoring, onsite inspections, testing, and enforcement that is specifically designed for TB drugs. Production consistency in terms of batch sizing is analyzed, postmarketing surveillance is performed, and inspections are carried out at non-domestic manufacturing sites that respond to international tenders.

In terms of capacity, Brazil has a National System for Sanitary Surveillance based on the model of an independent NRA, Anvisa. The system in Brazil includes a national laboratory institute, the National Institute for Quality and Control, responsible for quality and control testing, developing reference materials, and administering proficiency-testing programs to accredit labs in the 27 states that meet the appropriate technical standards. A specific TB Drug Quality Testing Program has tested all FLDs and SLDs in use since 2004, according to national regulation policies for sanitary surveillance.

The program is conducted with the support of a working group that carries out its activities and monitors results and regulatory measures. The initial findings of the program revealed quality and labeling defects in 32 percent of the 70 samples analyzed,6 which were linked primarily to API quality and discrepancies among the analytical methods used by the NRA and the public manufacturers. The NRA notified manufacturers of products that failed to meet adequate quality standards, and the products were recalled.

Keravec maintained that the “working group” model has facilitated improved interactions between producers and regulatory authorities as they have undertaken efforts to improve drug quality and harmonize analytical methods by decentralizing quality testing to the state level. Transparency for stakeholders is ensured because reports on product quality are publicly and freely accessible. The implementation of the e-TB Manager database (described in Chapter 1, Box 1-4) has also enhanced the NTP’s capacity for pharmacovigilance.

“Vicious Cycle” of QA SLD Supply

Patrick Lukulay, USP, depicted SLD supply as being plagued by a “vicious cycle” in which there is a limited supply of QA API and QA FPP, while QA FPP volumes are also affected by the limited demand for QA drugs, including the poor diagnosis of MDR.

Lukulay differentiated between two components of QA: QC and quality of the manufacturing process (Good Manufacturing Practices). The former encompasses the quality of the attributes of the product, that is, presence of impurities, dissolution profile, ingredient identification, and microbial content (for injectables). Manufacturing process control helps ensure that drugs that meet QC standards are also produced in an environment appropriate for drug manufacturing. A facility could, for example, be prone to contamination or a product might not have been provided with sufficient documentation to be tracked if problems arise. QA medicines satisfy both components.

Limited supply of QA API is a serious barrier that affects lead times, price, quality, and prequalification of FPPs. Lukulay suggested there is an urgent need for more API suppliers to voluntarily seek WHO PQ in spite of the capital and human resources investment that the process entails. Entry into the API manufacturing industry is severely restricted by the complexity and cost of production. Lukulay’s analysis revealed that in terms of cost/reactor volume, China (followed by India) has the lowest current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) and operating costs in the

___________________

6 Thirteen percent failed due to labeling and 19 percent failed due to tests.

world. China is the world leader in fermentation chemistry in part because its petrochemical industry, on which API production technology relies, is relatively far advanced. The combination of fermentation technology and low cost per volume explains why China produces 80–85 percent of the world’s TB APIs, including SLD TB APIs.7 He noted that low capacity use for API plants causes significant price increases, underscoring the need to fill idle plant capacity with full batch sizes to reduce product costs. While QA depends on a number of factors related to manufacturing and capacity, the tension between assuring quality and speeding treatments to patients was also discussed by several workshop participants (Box 2-1).

FORECASTING AND INFORMATION MANAGEMENT

Workshop discussions included a focus on selected issues of demand that affect and impede the entry of SLDs into countries. This section of the report provides an overview of the key roles that improved demand forecasting will need to play in addressing demand-side challenges to the SLD supply chain. O’Brien provided a synopsis of demand-forecasting fundamentally, described ways in which SLD demand forecasting methodology could be improved, and explored the impact of accurate and credible demand forecasting for suppliers. Hamish Fraser, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, and former Director of Informatics and Telemedicine, Partners In Health, provided an overview of how information management systems could be employed to improve patient management, track demand, and strengthen and improve transparency of the supply chain.

Demand Forecasting8

O’Brien articulated several tendencies prevalent in the field that can hamper both the practice of forecasting and the way results are interpreted, and offered suggestions for establishing a more effective forecasting process. While it can be tempting for both the forecaster and the consumer to gloss over the details on which a forecast is constructed, it is important not to skip over them: multimillion dollar investments and delivery of treatment to huge patient populations can be predicated upon those details. It is less helpful to construe forecasts as either “right” or “wrong” than it is to strive

___________________

7 Further advantages: China’s petrochemical industry is able to generate the starting material, intermediates, and solvents necessary for API production, and its transportation infrastructure is able to support bulk material logistics. At present, 50 percent of starting materials and intermediates are imported from China to the Indian pharmaceutical industry.

8 This subsection is based on the presentation by Meg O’Brien, Director, Global Access to Pain Relief Initiative, American Cancer Society.

to generate “more useful” ones. Applying the analogy of a complex calculator, the forecasting process should begin by understanding the consumer’s needs9 and follow with the construction of a logical framework to abstract reality into a simpler model. A good model should be “superficially simple and covertly complex.” The framework can incorporate both recent experience and the impact of the specific market and demand drivers to account for future uncertainty. Also helpful is clarifying the consumer’s time horizon and restricting the forecast primarily to that time frame. Relevant, carefully selected data (ideally collected in a standardized way) should then be used in the model to produce and check results. Finally, the results should be communicated to the consumer in a way that does the following:

• satisfies the consumer’s main objective;

• explicates the logic behind the model;

• makes assumptions clear;

• anticipates questions; and

• establishes the forecast’s credibility.

O’Brien noted that a properly designed and credible demand forecast can play a key role in aligning product prices with their true costs by reducing demand uncertainty and improving visibility into expected orders. It is important to distinguish among need, demand, and procurement in forecasting: need refers to volumes required to treat all patients, demand to volume that will actually be used, and procurement to volume that will actually be purchased.

There is a distinction between aspirational and realistic forecasts. Political and national program objectives can drive forecasting toward unrealistic outcomes. For example, an organization might choose not to release a forecast that undermines or contradicts a highly publicized treatment objective (e.g., the WHO “Three by Five” ARV [antiretroviral] forecast). Similarly, a forecast might be manipulated to align with an aspirational national program objective, but then fail to constitute a realistic forecast for suppliers. O’Brien maintained that forecasting should ideally be performed in conjunction with both market generation and serious commitments to seeing orders through, as well as following up on forecasts to check for accuracy. Such efforts can help to “make sure that reality looks like your forecast” when trying to attract new products and suppliers to a market.

Prashant Yadav, University of Michigan, suggested that a process of consensus forecasting could be useful in creating a platform to synthesize different forecasts that have been generated for MDR TB SLDs. He cited

___________________

9 For example, does the consumer need a precise estimate, generally plausible estimate, minimum/maximum, plausible range, or a yes/no answer?

BOX 2-1

Considering Two Key Priorities in the Donor-Funded MDR TB Market: QA and Treatment Access

A theme that emerged during the workshop was the tension inherent in trade-offs among cost, access, efficacy, and QC in the provision of SLDs for MDR TB treatment. A focal point of the issue is how these factors are affected by the regulatory structures through which SLDs are channeled in the donor-funded supply chain.

Expanding Access to Treatment

One perspective, expressed by some, including Salmaan Keshavjee, Director, Program in Infectious Disease and Social Change, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, is that the system should be designed with a primary focus on ensuring that more patients in need receive “good-enough” quality drugs in the quickest possible way, arguing that the current focus on ensuring the most controlled and monitored treatment is a limitation of the system. He said the system should be redesigned to be decentralized, with a priority focus on lower prices, increased drug supply, and expansion of the number of patients who can access treatment. For example, he suggested that countries should be permitted to procure drugs directly from manufacturers as long as they are QA through a mechanism like the Global Fund’s 90-day rule, which allows a country to use second tier–level drugs if optimal quality drugs are not available within 90 days. As Andreas Seiter, Senior Health Specialist, Pharmaceuticals, Health, Nutrition, and Population, World Bank, commented, significantly lower prices can be achieved through this type of direct procurement. Norbert Ndjeka, MDR TB Director, Department of Health, South Africa, noted that countries like South Africa procure drugs without WHO PQ status from the same manufacturers that supply the drug with WHO PQ to GDF. Several other speakers reinforced the point by noting that countries desire the authority to regulate their own QA.

More broadly, Keshavjee suggested that definition of quality should be put on a spectrum in such a way as to prioritize the provision of comprehensive access to treatment. That is, instead of “not treating people because we don’t believe that the drugs that are available 10 feet away from them in their local pharmacy are good,” he suggested engaging the private sector and in-country leadership to focus on providing quality treatment in the immediate term while employing mechanisms to “move those governments toward quality” in the longer term. Similarly, he suggested that determining a country’s or program’s eligibility for the

GLC mechanism in terms of compliance with QA standards should be framed as a process rather than an end point. That is, these countries or programs should be allowed to access drugs while being facilitated in working toward achieving compliance.

Avoiding a Double Standard of Treatment

The alternative perspective, expressed by several other workshop participants, maintains that the absence of stringent centralized regulation gives rise to an unacceptable “double standard” of MDR TB treatment, whereby some patients in some countries receive drugs of poor quality while those in other countries receive drugs of good quality. Myriam Henkens, International Medical Coordinator, MSF, stated that such a double standard is unfair because all patients deserve quality drugs. She argued that it is “our role to fight for that and make that clear” and suggested that patients should also be educated to insist on quality drugs and to hold their governments accountable for providing them.

Peter Cegielski, Team Leader for Drug-Resistant TB, International Research and Programs Branch, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, CDC, said that in addition to a double standard in terms of drug quality, in a broader sense the TB control community has also promoted a double standard regarding the diagnosis and treatment of TB for the past 20 years that is finally being overcome. He suggested that this is one of the causes of the current difficulties in diagnosing and procuring drugs for MDR TB patients.

Amy Bloom, Acting Chief, Infectious Diseases Division, USAID, articulated two key pharmacoeconomic questions that will need to be addressed in order to reconcile the differing perspectives and inform the potential restructuring of the system. The first is to decide whether treating more patients with drugs of questionable quality at lower cost is worth the risk in efficacy. The second is to determine the “real” respective costs of treatment with drugs that have passed through established centralized QA regulatory pathways, drugs that have passed through decentralized QA processes, and drugs of poor quality.

Lisa Hedman, Project Manager, WHO, stated that an evidential link between drug quality and actual patient outcomes had yet to be concretely established and warned that current data are insufficient to support a “risk-based” approach to QA. She stated that available data show real problems, citing as an example a case study documented by CHAI in India in which QA policies for locally procured medicines and donorfunded procurement policies were operating as discrete systems within the same country, and a quality two-tiered market emerged between QA and non-QA products.

the field of malaria, where a tripartite consortium develops three separate forecasts using different assumptions, different data, etc., and then meets to compare results and reconcile their differences to generate a combined forecast that is communicated to manufacturers. O’Brien concurred, on the basis of her experience in group forecasting with shared data in other fields, that consensus forecasting has the potential to improve forecasting and coordination. She warned, however, that it is important to properly harmonize data via systematic comparison and to establish a collective means for evaluating different forecasts and their underlying assumptions.

Information Management10

The field of information management can be applied in multiple ways to address issues associated with the MDR TB supply chain. Fraser emphasized that improving the efficacy and breadth of information management systems could concomitantly increase demand-forecasting accuracy; increase supply chain transparency; and improve health system strength, scalability, and sustainability. He listed a number of core variables11 that should be collected and quantified with respect to the SLD supply chain, adding that although they are not difficult to collect in principle, they can be challenging to implement without good tools and training.

Electronic Medical Record (EMR) Systems

In what represented an early move toward integrating information management into the broader health system, a Web-based EMR system was designed in 2000 to support a Partners In Health project to scale up MDR TB treatment in Peru. Data collected about laboratory results, including sputum smears, cultures, and drug sensitivity tests; treatment regimens; and other types of records were used for various clinical, programmatic, and clinical research purposes (Fraser et al., 2006). For example, collection of drug regimen data was prioritized and used to improve QC, and then aggregated to assess monthly requirements. The aggregated data could then to be linked to price lists and combined with recruitment rates as well as with time and length of treatment. Eventually, models based on these data were used to generate forecasts of drug requirements 6 months or more in

___________________

10 This subsection is based on the presentation by Hamish Fraser, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, and former Director of Informatics and Telemedicine, Partners In Health.

11 Such variables include demographics, program enrollment date, start date for drugs, drug regimen, treatment status, treatment outcome and date, smear and culture results, DST results, other lab data (hematological, biochemical), previous medications, adverse events, and socioeconomic factors.

advance. Fraser questioned why such established tools are not being further developed or implemented more widely.

Fraser cited Keravec’s e-TB Manager as another important innovation in MDR TB drug and information management. The OpenMRS (Open Medical Record System) project is an example of a non-disease-specific EMR initiative12 that permits redeployment of a horizontal approach to vertical uses. Its broad framework can be tailored to support the management of various diseases by customizing its language, concept dictionary, and open-source modular design.13 Furthermore, a system like OpenMRS might provide an opportunity for private-sector health care professionals (HCPs) in countries like India, where they are not part of national MDR TB initiatives, to communicate more effectively with the public sector. An OpenMRS system could offer tools for a range of diseases but have embedded key functionality for MDR TB. As with all personal health data, however, confidentiality and ownership of data is an important concern. Well-designed systems using existing technology can ensure security and encryption, but it is essential to properly train and supervise staff, and to develop stronger national policies and laws to protect such data in developing countries that often lack such regulation.

Information Technology Suggestions for MDR TB Supply Chain

Fraser offered several concrete suggestions, or “low-hanging fruit,” that might drive efforts to improve the MDR TB SLD supply chain, as follows:

• There is a need for better standardized national and international coding of medical products in order to track and map shipments.

• If products all bore internationally agreed-upon bar coding containing name, batch number, expiry data, and authentication ID data, accuracy and workflow could be dramatically improved.

• Standardized reporting formats for drug stocks and status could improve both private- and public-sector transparency and stock-out monitoring.

• The OpenBoxes shipment tracking and inventory management system14 is another broad system covering a range of supply chain requirements that might integrate with the MDR TB SLD supply chain.

___________________

12 Collaborative project between Partners In Health, Regenstrief Institute in Indiana, and the South African Medical Research Council (www.openmrs.org, accessed October 18, 2012).

13 An example of OpenMRS customized for MDR TB can be viewed at www.openmrs.org/demo (accessed October 18, 2012).

14 Open-source software developed by Partners In Health.

Lucica Ditiu, WHO, suggested there is potential for data collected to contribute to reporting and integrating TB care with other treatments such as HIV and malaria. Fraser commented that investments into systems for HIV (like PEPFAR) have unfortunately not developed into common tools for use beyond HIV. Fraser suggested that as a matter of priority, national health authorities and funding agencies should be made aware that the development of common tools is not that much more expensive than the more prevalent disease-specific ones, and that they provide a better mechanism for efficient drug supply and dissemination of information and reports.

Keravec suggested the strategy of translating country- and facility-level demand forecasts based on reliable data (e.g., pace of enrollment, consumption, and real number of patients being treated) from information systems into usable data for GDF. GDF could then supplement this with its own data (e.g., orders, lead times, production, and shipment schedules) to develop an early-warning stock-out system.

Workshop discussion included examination of supply-side issues affecting the entry of SLDs into countries, with specific focus on the causes, impact, and prevention of supply chain shortages. Perrin provided an overview of common problems that lead to supply chain shortages at both the country and global levels. Jim Barrington, Global Program Director, Novartis, described the SMS for Life model for preventing stock-outs of malaria medicines in African countries. Cegielski demonstrated that TB and MDR TB drug shortages are a problem not only for low-income countries by describing the effect of such shortages in the United States.

Causes of National- and Global-Level Supply Chain Shortages15

Perrin emphasized the importance of setting and maintaining international quality standards for drugs and the benefit that the WHO PQ program provides in that regard to low-income countries. He also acknowledged the Global Fund’s and GDF’s efforts to align their QA policy with WHO PQ and other SRAs. Purchasers and funders were urged to foster demand for QA SLDs in order to incentivize reliable manufacturing and limit risks to individuals and public health.

___________________

15 This subsection is based on the presentation by Christophe Perrin, QA Pharmacist, The Union.

Perrin remarked that international donors and procurement agencies often fail to consider an NTP to be their main “customer,” focusing instead on their own internal organization and procedures; this leads to the NTP not being appropriately informed and updated about the logistics of its procurement once the order has been placed. A participant elaborated that when NTPs in this situation are faced with unexpected drug shortages due to being kept “out of the loop” by international agencies, they are often unfairly blamed for the problem.

Another common issue described by Perrin is the lack of visibility by the NTPs into the supply chain, which can lead to disruption and necessitate emergency orders due to resulting shortages. NTPs often lack adequate human resource capacity, leading to a lack of harmonization among donors and further straining their staff, who attempt to manage different processing and quality requirements. Discrepancies between actual diagnoses and the volume of SLDs ordered can result from inadequate data collection and forecasting competencies and can also lead to shortages.

Potential country-level solutions that Perrin suggested include strengthening NTP leadership and centralizing SLD supply chain coordination, and increasing human capacity for consistent program management with training programs led by qualified staff from donor agencies.

Global-Level SLD Shortages

Perrin outlined common causes of SLD shortages on the global scale. Global reliance on a single source for QA API or on an extremely limited supplier pool can lead to shortages when demand far outweighs supply capacity. A related problem is that minimum volume thresholds for orders can cause unexpectedly increased lead times. He reported that in 2010, the majority (56 percent) of shortages in Global Fund grants for TB were due to weak procurement and supply management capacities.

Perrin offered potential global-level solutions aimed at different components of the system, as follows:

• QA manufacturers could be incentivized via demand forecasting and expansion, transparent bidding processes, advance purchase commitments (APCs), and smoother regulatory mechanisms.

• Donors could implement revolving fund mechanisms and harmonization initiatives to shorten delays.

• Donors and procurement agencies could allow manufacturers seeking to reach minimum production thresholds to access a centralized SLD stockpile.

• WHO and donors could provide financial and technical support for innovation (new compounds, shorter regimens, packaging allowing longer shelf lives, etc.).

• Donors, countries, and procurement agencies could work to streamline forecasts of needs, order planning, and disbursement of funds.

Several participants referenced the limited shelf life of SLDs (24 months) and how this affects availability of drugs within the global supply chain. Pre-made SLDs can sit in a manufacturer’s warehouse for weeks or months before the appropriate paperwork is completed for shipment, all while an already short shelf life deteriorates further. It was also referenced that ministries of health can often require receipt of SLDs with a predetermined percent of the shelf life preserved (e.g., 70 percent shelf life), which heightens the challenge of efficiently procuring SLDs from a manufacturer and distributing in-country.

“SMS for Life” Model for Preventing Stock-Outs16

Barrington said the SMS for Life project17 was formed in response to the huge problem of malaria drug stock-outs at health facilities in Africa, the major cause of which is a lack of adequate information management and provision. The program facilitates patient access to medicine and eliminates stock-outs by using an SMS system to monitor stock levels and to collect surveillance data at remote health facilities. Collected data are used to generate reports delivered via the Internet and mobile phone to the reporting hierarchy. Key design criteria for the solution were usability in the targeted environment, capacity for scale-up to an unlimited number of health facilities and countries, affordability,18 availability as a subscription service with no requirement for initial or future technology investments or management, commercial sustainability for service providers, and reliability proven via initial implementation in the pilot country at scale.

To date, the program has been implemented in all public health and faith-based facilities in Tanzania and in pilot districts in Kenya and Ghana, with implementation planning in progress in Cameroon and the Democratic

___________________

16 This subsection is based on the presentation by Jim Barrington, Global Program Director, Novartis.

17 In partnership with IBM, Vodafone, Google, Ministry of Health in Tanzania, Novartis, and Roll Back Malaria Partnership.

18 The system was designed to be affordable in the poorest countries without requiring donor funding. The overall total cost was capped at $100 per facility per year with procedural and training materials provided free of charge. The system also needed to be offered via subscription service with no investment required.

Republic of the Congo. Scale-up to more countries and/or to cover more products and commodities would require funders to redirect funding into strengthening systems and operational projects for improved stock management at the health facility level and management of drugs in-country and at health care facilities after they are received in-country.

On a broader level, Barrington suggested that funding mechanisms would have a greater impact if they reallocated more resources toward systems strengthening. To that same end, he asserted that funders should take on both the obligation and accountability for outcomes; that is, they should seek to ensure that drugs are actually received by patients, not just to ensure their procurement and delivery into the country.

Potential Consequences of Data Transparency

Participants addressed possible repercussions of total data transparency for the countries that are beneficiaries of programs like SMS for Life. Brenda Waning, Coordinator, Market Dynamics, UNITAID, WHO, commented that this program holds governments to a strict and public level of accountability, to which they may be resistant. She continued that the application of such a program to an MDR TB program could be even more risky because the criticism of public and press in response to stock-outs would fail to account for the complexity of SLD procurement. Although several participants agreed that information should be made available, there was some disagreement as to whether it would be feasible for the data to be fully disclosed (and not “owned,” e.g., by a Ministry of Health), or whether there are limitations on the extent to which data can be made available at the health facility level due to its high value and resulting security concerns.

TB Drug Shortages in the United States19

Cegielski highlighted the issue of TB drug shortages in the United States to illustrate that the problem is not exclusive to low- and middle-income countries, nor is it limited in the United States to TB drugs alone.20 He described the results of an unpublished survey that was undertaken in 2010 through the National TB Controllers Association to assess drug shortages

___________________

19 This subsection is based on the presentation by Peter Cegielski, Team Leader for Drug-Resistant TB, International Research and Programs Branch, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, CDC.

20 Between 2001 and 2011, 1,190 shortages were recorded using FDA’s voluntary reporting system.

in state and local TB programs. Of the respondents, 64 percent reported problems with MDR TB drug procurement in the preceding 5 years.21

Cegielski reported that the most common reasons for the shortages were nationwide shortages (95 percent), lack of funding and drug price (62 percent), shipping delays (71 percent), regulatory delays (50 percent), and payer issues (~30 percent). The number of shortages22 increased from 70 to 211 between 2006 and 2010, and as of September 2011, kanamycin was not available, streptomycin was out of stock, and capreomycin and amikacin were very difficult to procure. The shortages had direct negative effects on patients, according to the same survey, including delays in treatment initiation (58 percent), treatment lapses and interruptions (32 percent), and the need to be prescribed a suboptimal treatment regimen (26 percent). Cegielski stressed that dealing with these shortages depletes the time and human resources of clinic management.

Key Messagesa

• National regulation of SLDs is essential, as there is no international mechanism to monitor for and ensure QA.

• The SLD supply chain is characterized by a negative cycle arising from the limited number of suppliers of API and FPP coupled with decreased demand for QA SLDs from certain areas.

• There is a need for better demand forecasting, and there is a need to distinguish between aspirational forecasting and realistic forecasting.

• Innovations in information management may offer improvements across many aspects of the SLD supply chain, from tracking of treatment to demand forecasting to reduction of stock-outs.

___________________

a Identified by individual speakers.

___________________

21 Cegielski cautioned that only 33 of 61 reporting areas responded, so the results might not be generalizable.

22 Including isoniazid, rifampicin, cycloserine, ethambutol, rifabutin, amikacin, kanamycin, and streptomycin.