Measures of Medical Care Economic Risk and Recommended Approach

This chapter considers various methods, including retrospective and prospective approaches, to constructing a measure of medical care economic risk (MCER) and then outlines the panel’s proposed approach and recommendations. As stated in Chapter 1, the sponsor’s charge to the panel included conducting a public workshop to critically examine the state of the science in the development and implementation of a measure of medical care economic risk as a companion to the new Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). From the workshop, commissioned papers, and our deliberations, the panel considered retrospective and prospective measures of the risk of incurring high out-of-pocket medical care expenses relative to income, the variability of risk across populations, and the differential vulnerability of groups with different health and coverage status.

The chapter focuses on developing the concept of MCER as distinct from economic burden due to actual medical care expenses, which is addressed in Chapter 2 (see also Meier and Wolfe, in Part III of this volume). The outcome of interest is a measure of risk, for example, the expected number (or fraction) of families and their individual members who, as a result of out-of-pocket spending for medical care services and premiums, would be in poverty or some multiple of poverty as defined by the SPM. For the medical care risk to differ from the medical care burden of large expenditures, it must be based on the distribution of future out-of-pocket expenditures that an individual or family may face given their characteristics at some baseline point in time. Thus, it is inherently a forward-looking or prospective measure as distinct from the burden measure, which is both retrospective and a statement about averages rather than distributions.

In the remainder of the chapter, the panel

- sets out a more developed concept of MCER;

- reviews the merits of a refined and information-rich prospective measure as compared with a simpler retrospective measure;

- presents a retrospective measure of MCER based on the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC);

- sketches a prospective measure based on the 2-year Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) longitudinal file;

- considers how best to use information about individuals to ultimately construct a family-based measure of MCER; and

- notes the issues that are not addressed by the panel’s recommended strategy.

A CONCEPT OF MCER

A core goal of health insurance is to pool risks of potentially high medical care costs across the population and over people’s lifetimes. Through health insurance, families lower their financial risk and have a more predictable expense in the form of an insurance premium that, in theory, can be budgeted for as a share of income and resources. For the insured, MCER thus has two components—premiums and out-of-pocket expenses for medical care not covered by insurance. For the uninsured, MCER has only the out-of-pocket component, although the uninsured may well experience other adverse effects, such as delaying needed care and experiencing anxiety from the lack of insurance coverage. The discussion below discusses ways to assess the financial risk.

A measure of MCER is needed to answer the following questions: What kinds of health events will push families or individuals into poverty or otherwise substantially compromise their financial well-being? What is the chance of those events occurring to different kinds of families? How do such events differ for different kinds of people? Because spending on out-of-pocket expenses for medical care services is not normally distributed, other measures besides the mean and variance are needed to adequately reflect the distribution of medical care out-of-pocket spending for families with different characteristics. We have identified two different situations to use for expressing the prospective risk that a family or unrelated individual faces.

1. One uncovered hospital stay away from poverty: What would happen if a family had a major out-of-pocket expense, such as that for an average-sized hospitalization? Might that be sufficient to push the family

below the SPM threshold? (The answer depends on insurance coverage, out-of-pocket payments for premiums, and cost-sharing for services received.) What is the probability of such an event, given the characteristics of that family and its members, including income and type of insurance?

With employment-based coverage or either Medicaid or Medicare, the risk that out-of-pocket spending for medical care services impoverishes a family is probably smaller than otherwise. Likewise, in a relatively young population, the probability may also be small because of lower health risks. In contrast, low-income working families who do not qualify for Medicaid or employer-sponsored group insurance could be expected to pay more out-of-pocket for medical care, with a risk of falling below the SPM threshold that will vary according to family members’ health. If such families bought insurance on their own, the full cost of premiums would contribute substantially to their out-of-pocket medical care spending.

2. If family income is low enough, even a small health shock with moderate out-of-pocket spending might push an individual or family into poverty. For those closer to the poverty threshold, it might not take much of a medical event or episode of illness to push the family to or below the threshold. Even in good health, families with incomes less than the poverty threshold are poor. What happens to people who become sick in those families?

We propose to quantify the concept of risk for a family as the estimated probability that next year’s medical spending is greater than the difference between the family’s SPM poverty threshold and its resources as defined for the SPM, with two differences—first, actual out-of-pocket medical care expenses would not be subtracted from resources (in contrast, the retrospective SPM poverty measure does subtract such expenses from resources); and, second, a small percentage of liquid financial assets would be added to SPM resources (as recommended in Chapter 3) as soon as there are data to make that possible.1 For families whose resources defined as above fall below the SPM poverty threshold, the estimated probability is 1 (100 percent), whereas for millionaires with insurance with a maximum out-of-pocket spending limit, the estimated probability is 0. Many Americans will have some estimated probability between 0 and 1, which means that they will not be in poverty when healthy but that some possible level of medical care spending will push them into poverty.

_______________________

1 Because the proposed quantification of risk is rooted in the SPM, projected medical spending needs to calculated at the family level, using the SPM definition of family (see Chapter 2). Later in this chapter, we discuss the relative merits of family versus individual-based approaches for predicting family out-of-pocket medical care expenditures.

The measure of MCER that we propose in this chapter addresses both of the situations above: for middle-income families with a high cap on cost-sharing, family medical care out-of-pocket spending at the 90th percentile of the distribution of out-of-pocket expenditures could be enough to push them into poverty; and for families close to the SPM threshold, the 50th percentile of medical care out-of-pocket spending might be enough. From calculations based on suitable data on each family’s distance to the SPM threshold and the distribution of their expected out-of-pocket expenses for medical care, one can summarize in tables or graphs what fraction of families will be pushed into poverty by expenditures of a specific size or at each level of future income as a percentage of the SPM threshold.

Furthermore, one can ask whether a particular event or set of chronic and acute illnesses would move a family down to 150 percent of the poverty threshold or any other multiple of the threshold compared with the situation when its resources were not this low and its members were healthy. One can also distinguish the effect on available resources of out-of-pocket premiums from the effects of other medical care out-of-pocket spending beyond premiums.

THE IDEAL VERSUS THE FEASIBLE: DATA NEEDS, TIMELINESS, AND REFINING A MEASURE OF MCER

“Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.”2

To understand the effects on available family income across the U.S. population of various kinds of financial exposure to medical care costs, one needs to calculate the probability for families with particular characteristics of having out-of-pocket premiums and spending on medical care services greater than their resources minus the SPM threshold (excluding the correction for out-of-pocket spending for medical care and adding a portion of liquid assets). Ideally, the calculation would reflect the actual terms of health insurance coverage; the age, gender, and health status of family members; and the composition of the family for a large number of families.

Practically speaking, the calculation must be constructed on the basis of information that is available from MEPS or the CPS ASEC (which is the basis for the SPM calculations). These surveys, however, do not include finely detailed information on plan coverage (which affects both out-of-pocket premiums and spending for medical care services). Moreover, the annual cross-sectional CPS ASEC does not document transitions in insurance status, which can occur for many reasons, including loss of a job and changes in health status, such as the acquisition of Medicaid by a low-income

_______________________

2 Box and Draper (1987:424).

woman who becomes pregnant (which would also affect her premiums and spending for medical care). The CPS ASEC has very limited information on health status and does not collect information on financial assets, a portion of which we recommend be included in resources for measuring MCER. MEPS follows families over 2 years, permitting the use of characteristics in year 1 to predict out-of-pocket premiums and services spending in year 2, consistent with the notion of risk, but MEPS has one-fifth the sample size of the CPS ASEC, and there is a significant delay until MEPS data are available for analysis.

The trade-offs in the choice between these two surveys lead to the two-pronged strategy outlined in the following two sections. See also the discussion of data sources in Chapter 5 and in Czajka (in Part III of this volume).

USING RETROSPECTIVE DATA TO CALCULATE MCER

Although the concept of MCER is prospective, we discuss how 1 year of retrospective cross-sectional data could be used to estimate a risk measure. One does not need to have prospective data or repeated measures on a family over time to measure risk. Indeed, the retrospectively determined burden of out-of-pocket medical care spending for a given year—and the proportion of people whose medical burden pushed them into poverty last year—can be used as a simple predictor of MCER in the following period. A retrospective burden-based measure of risk will be significantly easier to calculate than the aggregate and relative likelihoods that, based on certain characteristics, families will be reduced to poverty in a future period. At the same time, a burden-based measure may not be as informative regarding the characteristics that are related to risk and the distribution of risk, as a prospective measure that is developed with 2 years of panel data for the same families. We draw these distinctions out below.

Using Cells with 1 Year of Data

In principle, one can develop estimates of MCER based on cells of families with similar characteristics or by multivariate regressions of family-level out-of-pocket medical care spending.3 Each of these methods, regression and cell-based, can be interpreted as a metaphor for what insurance does. The regression approach can be seen as people investing in their own future, with small losses from the premium when health spending is low transferred to pay medical bills in the less frequent periods when spending

_______________________

3 The cell-based approach can be thought of as a regression model with mutually exclusive categories. We use the term multiple regression to describe models that do not necessarily have mutually exclusive categories or cell indicators.

is very high. The cell-based approach can be seen as people getting together so that those who are fortunate in health, with low out-of-pocket spending, subsidize their unlucky neighbors.

Cell-based approaches group similar people or families into cells, and then they use the medical care spending experience of the members of a cell (this year’s experience to create not only a measure of burden, but also one of risk) as a proxy for the range of possible outcomes for each member of the cell (next year’s risk). If all the families in a cell are equivalent ex ante, as reflected in base-period health status, demographic characteristics, insurance coverage, and income and other resources, then the average of their experience on out-of-pocket expenditures is an estimate of burden. For risk, one can use the observed dispersion across the families within the cell or estimate the probability that some family reaches one of the common poverty thresholds (50, 100, or 200 percent of poverty). The observed probability of an out-of-pocket expenditure sufficient to take the family below the poverty threshold is an estimate of the risk for each member of the cell because the cell is homogenous in terms of observable characteristics and risk adjustors. The advantage of this method is that it needs only 1 year of data, which has two benefits—timeliness and allowing the use of nonpanel data like the CPS ASEC.4 A disadvantage is that because nonpanel data sources systematically exclude recent deaths and those who have entered institutions in the immediate past time period—two groups known to have high health expenditures—it will be necessary to use other data sources and the relevant literature to provide an estimate of the missing information for those two transitions and their impact on out-of-pocket medical care spending. Although decedents and institutionalized people are not in poverty, the transitions to death and to institutions will often impose major drains on their families’ resources and could push other members of the household into poverty.

The cells for the retrospective measure must be formed on the basis of characteristics that predict spending. These characteristics and their weights used to build cells typically come from preliminary analysis using a regression approach that calculates an individual’s expected payments based on observable characteristics in a prior year (including diagnoses or other health information) from other data sources, such as MEPS. A problem is that, to actually produce the estimates of retrospective MCER from a data source such as the CPS ASEC, the characteristics that predict

_______________________

4 As discussed in Chapter 5, the CPS employs a panel sample design in that monthly samples rotate in and out of a sample on a schedule that ensures that 75 percent of the sample addresses in a given month were included in the previous month’s sample, and 50 percent were included in the sample 12 months earlier. The purpose of this design feature is to reduce the sampling variance for estimates of month-to-month or year-to-year change—not to enable longitudinal analysis. The limitations of the CPS ASEC for longitudinal analysis—and why we do not propose such use here—are explained in Chapter 5.

out-of-pocket medical care spending must logically be defined at the start of the year in that data set. So, cells cannot be defined by current spending because that would produce overly small observed variation in spending. Similarly, health characteristics and the risk adjustors based on them that predict spending may be the result of health shocks throughout the year and not defined at the start.5 In most data sets, some covariates are measured before and some measured afterward. For example, one typically knows income at the end of the year, not before.

If in the past year a given percentage of families had out-of-pocket spending for both premiums and care received, then one could use data on the expenses incurred to say that families with certain characteristics were more or less likely to fall below the poverty threshold last year. If the world were in a steady state—that is, there were no changes in the general cost of care, insurance plans, mandates, or the business cycle—then that retrospective analysis would provide a consistent prediction as long as the covariates were measured at the start of the year. Two-year panels solve this problem by using first-year information to predict second-year behavior.

In the CPS ASEC, one could use also logistic regression of an indicator defined as out-of-pocket medical care spending greater than or equal to the difference between SPM-adjusted income (without the subtraction of out-of-pocket spending) and the SPM family characteristics. The same caveats on when predictor variables are measured would apply.

An Initial Retrospective Measure of MCER

In the short term, with the data now being collected, the CPS ASEC could be used to report the burden of out-of-pocket medical care spending retrospectively, roughly 10 months after the end of the calendar year for which income and spending are reported. Furthermore, with additional assumptions, the retrospective measure of burden could serve as a proxy for the prospective MCER: for example, if x percent of families and individuals were moved into poverty this year, then the same x percent is the best estimate of those who will be in poverty next year, assuming no other major policy initiatives or differences in the business cycle.6

_______________________

5 If one develops risk adjusters for health conditions based on 1 year of health experience and uses that experience to explain expenditures for that year, one would arrive at a biased assessment of the variance because the covariates are not independent of the out-of-pocket spending (see Manning, Newhouse, and Ware, 1982).

6 The preliminary analysis of MEPS, discussed below, could help to identify which family characteristics were most important in predicting out-of-pocket medical care expenditures. Instead of relying on parametric models, the probability of a family being at or near poverty could be determined empirically if risk cells were based on particular family or individual characteristics.

Using the range of cell mates’ experience this year as the distribution of possible expenditures next year for each individual or family in the cell permits the calculation of distributions with only 1 year of cross-sectional data. Cells would be defined by families’ characteristics as close to the start of the year as data permit so that the rest of the year is prospective to those definitions. Individuals could be grouped into cells by predicted next-year expenses. Handel (2011), for example, uses adjusted clinical groups (a case-mix system based on claims-defined diagnoses) together with other characteristics to do this, but the diagnosis cost groups form of risk adjustment system, RxRisk (a risk assessment instrument that uses automated pharmacy data systems to characterize chronic conditions to predict future costs), or some combination of relative risk algorithms could also be used (see the description of methods for the Dutch health insurance system in van de Ven et al., 2007, for a mixed risk equalization/adjustment system). Either total expenditures or discrete types of expenditures could be grouped.7 The Gaussian copula methods used by Handel to combine different types of spending could be adapted to account for within-family correlation in grouping individual out-of-pocket medical care spending into a family-level variable.

To estimate the full range of spending next year from this year’s data, one must adjust for the general increase of spending to be expected next year, and for any people missing from the data. If the survey does not include people who died or entered institutional care during the year, their numbers and risk of spending experience could be estimated separately based on cell characteristics and the outcomes for these virtual people (who are missing at the follow-up survey) added to the range of possibilities in the cell for those who survived or who are in a noninstitutional setting by the end of the year. One could either base the cells on out-of-pocket spending or base them on total spending, and then use a standard insurance policy or actual terms of coverage to calculate the resulting out-of-pocket spending.

Each member of the cell would be assumed to have the same distribution, which should be acceptable for combining with their family resources and thresholds to calculate percentiles in the tail of the distribution that

_______________________

7 In the absence of detailed information on different coverage for different types of health care services, it may be sufficient to examine out-of-pocket expenditures combining all of the types of care or to group classes of insurance into the following categories: uninsured, public based on poverty or categorical eligibility, Medicare, group insurance. We are not aware of any major national data set that contains the level of detail on coverage that Handel (2011) has and that also has an adequate response rate and spans the age range necessary for this task. See the work of Goldman and colleagues on the Future Elderly Model, a demographic and economic simulation model designed to predict the future costs and health status of the elderly, at http://roybal.healthpolicy.usc.edu/projects/fem.html.

represent medical care economic risk. If the cells are big, say 200 cases, then experience within the cell will be a good estimate over the entire distribution. If the cells are small or if one wants to know more extreme tails, one will have to model them, or combine experience on rare events from many cells.

A PROSPECTIVE APPROACH BASED ON 2 YEARS OF DATA

Because this feasible set of calculations based on the annual CPS ASEC is somewhat informative, why should we continue to pursue construction of a prospective measure of MCER? What could be its added value? With its richer data on health conditions, distribution of medical care spending by service type, and 2-year panel, MEPS offers the opportunity to learn much more about the interplay of health status, health insurance, and out-of-pocket medical care spending with respect to family finances as well as to more accurately assess how risk varies with health. Over the next several years, as the landscape of health insurance coverage in the United States undergoes substantial change, understanding the underlying drivers of families’ choices of insurance coverage and their out-of-pocket health care spending and the effects on their resources will be extremely important.

With 2 years of data, as are available from MEPS, one can employ multivariate regression methods to develop predictions about expected outcomes or their distributions. The difference between this and the cell-based approach is that, with cells, one does not share information across different groups. In regression, however, the estimated model has a more limited specification and shares information across observations, under the assumption that the response to individual covariates can be jointly modeled. In reality, these methods are not exclusive alternatives. With limited data or if one combines responses across individuals in the same family, acquiring meaningful detail on risk may require a mixed approach.

Another alternative is to use data on second-period expenses and base-period characteristics together with multivariate regression methods to estimate the probability that a family with given income and resources, family composition, and health will have an expenditure large enough to push the family to the poverty threshold. In the absence of sufficient research on the distribution of out-of-pocket costs relative to SPM thresholds, it will be necessary to do that work empirically.8 For example, one would expect that a working poor family with one or more members in fair or poor health might have a substantial risk even without a hospitalization or high-cost drug regimens. An emergency department visit or a flare-up of a chronic condition might be enough to drop the family below the threshold.

_______________________

8 See the recommendations for research in this area on the following pages.

Moreover, if one allows for the baseline list of covariates to include insurance status but does not model the impact of next year’s expenditures as if that family maintained its baseline insurance status, one can avoid the concern that some individuals could have a moderate or very large health care expenditure that would lead them to be eligible for some programs (such as Medicaid) and thus have lower out-of-pocket medical care spending than if the same events had to be evaluated with baseline coverage.

Needed Research for a Prospective MCER Measure

The truly prospective measures that require 2 or more years of data, or with surveys that have complete baselines, imply moving away from the more timely CPS ASEC to other data sources. Here, there are a number of issues of limitations with currently available data. Just as important, however, is the dearth of relevant literature on which to base the models. Although substantial data are available on how mean expenditures of individuals respond to such individual characteristics as age, gender, and health and to such family characteristics as income and insurance status, there are very few data on the responses in terms of distributions or variances at either the individual or the family level. In the case of single-person families, there is no issue. But how does one combine the information across family members, when ages and health status vary so much across different family members? What types of statistical or econometric models perform well?

Of equal importance is the dearth of information on what factors predict out-of-pocket medical care spending. Clearly, insurance status will play as large a role as prospective illness, but not much work has been done on this. The panel found that although much is known about total health care expenditures, very little is known about family and individual covariates that predict family out-of-pocket medical care spending or family finances. This situation dictates an analytic agenda before highly specific recommendations can be made on a prospective measure of MCER.

Health services researchers and health policy analysts have substantial experience with mean expenditures adjusting for observable individual and family characteristics at the individual level. There is much less work that has been done on out-of-pocket medical care spending at the individual level.9 The panel’s examination of out-of-pocket medical care spending (excluding the out-of-pocket premium) from the MEPS data on adults in 2004 suggests that out-of-pocket spending for medical services has the usual health expenditure characteristics (Banthin and Bernard, in Part III

_______________________

9 A notable exception is the work by Dana Goldman and his colleagues on the Future Elderly Model. That study does not deal with general noninstitutionalized population, however (Goldman et al., 2004).

of this volume). There are zeroes for those who do not use health care services or have very generous policies. For those with any out-of-pocket spending, their spending is skewed, but not as skewed as total expenditures. The skewness is probably large enough to require attention. Whether the statistical methods used for total expenditures would be the same as for out-of-pocket expenditures either in degree or kind is not known.

We do not know which variables matter for out-of-pocket medical care spending. We suspect that chronic disease and age will matter because prescription drugs may not be fully covered by insurance. Because the fraction of the population with mental health or dental coverage is less than that with medical care coverage, one would expect that mental health status and oral health would affect out-of-pocket spending for medical services.

To get at the variability in the burden, one can look at the retrospective burden variance within cells, or one could employ multivariate methods for the variance of expenditures conditional on characteristics. Although models for conditional means of expenditures given characteristics of the family and its members are common at the person level, they are not at the family level. This may require some work for the variance function. But given the skewed characteristics of out-of-pocket medical care spending, it will probably not be sufficient to look at the mean and variance of such spending and total health expenditures at the family level. One would need to observe responses to deductibles and stop-losses to assess the impact on out-of-pocket spending. This has been done by Keeler and colleagues (1988) for the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. But that study required much more extensive modeling of behavior than one would expect the U.S. Census Bureau to do, or it would require more detail on insurance plan details than is commonly available.

As noted, for the mean family burden, one has only to add the conditional means for the individuals as long as the individual means condition on family composition and income. But for the distribution of out-of-pocket medical care spending or its variance, it is more complicated than keeping track of means, variance, and covariances among the family members.

Because there is much to learn about the drivers of out-of-pocket medical care spending for families of varying size, composition in terms of ages, health status, insurance coverage, and resources, we recommend a series of analyses based on MEPS to test out various alternatives and to answer such questions as what factors (e.g., chronic conditions) add to the predictive value of previous spending for future out-of-pocket spending. Such analyses are also needed to answer a series of questions about which approach to use in modeling a family’s out-of-pocket medical care expenses and risk as a function of individual characteristics (age, gender, health status) and family characteristics (income, insurance status—which may vary by family subunit). Past research on mean or adjusted health expenditures indicates

that the most predictive of variables include age, gender, and health status (status per se or case-mix and severity). But in moving to measures of the family distribution of out-of-pocket spending or its variance, how does one combine individual data into a meaningful model for the family? There is very little guidance on this score in the literature.

The panel thinks that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services needs to consider several possible alternative analyses to help better understand these issues. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, or both agencies need to perform a series of analytical studies using MEPS. The results of these analyses can be used to inform the move from a purely retrospective approach that uses medical care economic burden as a proxy for risk to an approach that estimates risk directly.

These studies should include an analysis of both the cell-based approach to estimating the expected amount of spending and the use of regression methods to understand the expected risks; both are important to the development of appropriate alternatives to the short-term strategy that we have offered. The needed analyses should address the following questions:

- At the family level, how does current out-of-pocket medical care spending or its two major components (out-of-pocket premiums and other out-of-pocket payments for services) predict next year’s out-of-pocket spending? How stable is this relationship in the near term?

- If one expands the covariate list to include other family characteristics besides the first-year out-of-pocket medical care spending, what relationships can be seen in terms of predictive ability?

- Because individual characteristics are the strongest predictors of future average expenditures, how does one roll up individual predictions into a composite family measure that is predictive of future family out-of-pocket medical care expenditures? If there is an indicator for having a chronic disease or cluster of diseases for any member of the family, how well does this (and similar family constructs based on individual health characteristics) predict future out-of-pocket spending in the prospective measure or explain burden in the retrospective measure?

- If one begins with the distribution of individual expenditure distributions net of observed individual and family characteristics, how does one best combine these into the family’s distribution around its expected amount? The Handel (2011) approach has some promise, but one needs to know how well that approach actually approximates the family’s distribution, especially in the

context in which different family members may have different insurance coverage.

- As an alternative to regression methods, a cell-based system needs to be developed based on a few characteristics of individuals within families and family characteristics. This may be coarser than what one would get with an ASEC cell-based approach because of the limited number of characteristics and sample sizes available.

In all of these cases, the panel is concerned about the overall distribution of out-of-pocket medical care spending more than the overall mean prediction. We are also interested in recovering the likelihood that a family with given characteristics will have an out-of-pocket spending large enough that its SPM-adjusted income less that spending falls below the poverty threshold or some specified multiple of poverty, such as those embedded in the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Recommendation 4-1: Given what limited work has been done in the field on issues in measuring medical care economic risk (MCER) prospectively, the panel recommends that appropriate federal agencies— the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, or both—perform a series of analyses using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to examine different prospective MCER measures.

These analyses would include different approaches to determine their relative performance. How does a coarser cell-based system compare with results based on multivariate regression? What is added by including more family and individual characteristics? How well do methods such as Handel’s approach perform compared with the specific (retrospective and prospective) approaches we suggest?

Recommendation 4-2: The panel recommends that the results of the analyses from Recommendation 4-1 be used to inform the move from a purely retrospective approach based on burden to a more prospective approach for measuring medical care economic risk.

Note that MEPS would be used for this comparison for three reasons: (1) it has multiple waves of short panel data available to start working with; (2) it has good measures of both health and medical care spending in one survey compared with other general population surveys; and (3) it separates out-of-pocket spending into premiums and spending on services. One would expect that as more people are covered or those who are covered have better insurance, the out-of-pocket premium component will rise

while the nonpremium component will fall because the demand for health care has been shown to be inelastic with respect to the out-of-pocket price (Newhouse et al., 1993). Understanding the impacts of the two separately as well as jointly would inform policy choices.

SPECIFIC ISSUES IN ESTIMATING MCER

We discuss below in more detail three specific issues in estimating medical care economic risk, which will need to be addressed in the analyses we recommend: family versus individual approaches to estimating MCER for a family unit, allowing for insurance plan choice and determining the predictors of choice, issues of selecting variables for cell determination or as covariates, and data and estimation issues.

Family Versus Individual Approaches

Our outcome of interest is the impact of MCER on family income, particularly for those families with relatively low incomes, who may be pushed below the SPM level by relatively high out-of-pocket medical care spending. However, one can predict family out-of-pocket spending from data on individuals in two ways. If one sums up individual spending into family spending before doing other analysis, one can try to estimate the family spending directly based on such family-level variables as age-gender mix, family composition, income and assets, and the mix of underlying health conditions, comorbidities, and severity of health conditions. Alternately, one can start with predicting the out-of-pocket medical care spending of individuals based on individual characteristics and then combine those predictions for each family.

It is generally easier to define a set of variables to predict future total or out-of-pocket medical spending for the individual than it is to define such variables for the family unit. Predicted individual out-of-pocket spending must then be combined for all family members to get back to family spending and to assess the likelihood that the family’s out-of-pocket medical care spending will cause it to fall below its SPM threshold. The estimated means for the family members can simply be added. However, the variability in out-of-pocket expenditures and more generally the distribution of family-level expenses also depend on the correlation among family members, which can reflect the family’s response to the joint budget constraint (because income is shared among individuals) or unobserved commonalities in preferences or health status. Thus, a method is needed for mapping from individual distributions to a family distribution that reflects the correlation in the underlying out-of-pocket (or total) expenditures of family members. If family members’ spending is positively correlated, the variance of the sum is greater than the sum of the variances of constituent members.

Similarly, it is harder to create cells of families whose spending is expected to be similar next year than it is to create cells of individuals with similar expected spending. In both cases, starting with families gets the correlation of family expenses automatically—but at a cost in sample size and in difficulty of defining the predictors. Moreover, past research has typically shown that the major drivers of mean expenditures are individual characteristics—age, gender, diagnoses, severity, and health status. Meier and Wolfe (in Part III of this volume) offer motivation for starting at the individual level and then aggregating to the family, taking an approach with some similarities to Handel’s Gaussian copula methods (2011). Parts of their argument seem eminently reasonable, not only because major determinants of out-of-pocket spending are individual (age, health status, and health shocks), but also because insurance coverage can vary for each family member.

A reason to favor a family approach is that joint decision making within a family about medical spending can be embedded in or overlap with insurance coverage and common access to family resources. Major determinants of health are not only individual (age, gender, and health status), but also family (collectively managed income and assets). For example, a family may not be eligible for Medicaid as a whole, but the children could be eligible for the Children’s Health Insurance Program and either or both parents could be eligible for health insurance from work or other sources. The family thus makes decisions subject to the terms of the separate insurance plans and an overall family budget constraint for out-of-pocket medical care spending and spending on other goods and services net of taxes and transfers. In addition, health shocks to one individual may be partially covered by his or her insurance, but the remainder will be paid with resources that could be used for the whole family in terms of health or other goods and services subject to relevant budget constraints.

Allowing for Insurance Choice and Predictors of Plan Choice

Although it is probable that choices and change in coverage will continue to occur, it is much easier to calculate burden and risk if families are assumed to stick with whatever coverage they have. If instead they are offered a menu of insurance choices, the model must decide whether to build in inertia (generally by assuming that only a random subset of families think about switching) and what criteria the families will use to make choices. Predicting plan choice needs to reflect both economic rationality and reality and so should ideally reflect out-of-pocket premiums, out-of-pocket spending on services, financial risk aversion, anxiety about difficult decisions between spending and health, and the value of care. If premiums are experience-rated, modelers must decide how quickly premiums are updated, which in turn affects adverse selection, death spirals, and other

market problems studied in this literature (Handel, 2011; Keeler, Carter, and Newhouse, 1998; Rothschild and Stiglitz, 1976).

Issues in Selecting Variables

Analysts need to be mindful of issues regarding the variables to be used in the cell determination or as covariates. One issue is that income and insurance are jointly determined with health care use. For example, there are time costs and losses in income that will be incurred if a person does not have full sick leave when visiting the doctor or recuperating from illness and hospitalization; see various reports from the Employee Benefit Research Institute showing the substantial fractions of workers without such coverage over the years. The sicker one is, the larger the loss if not covered by full sick leave. As another example, if a person qualifies for special insurance coverage due to pregnancy or to being categorically eligible (such as for renal dialysis), then he or she may be insured and have lower out-of-pocket expenditures than would otherwise be the case. Some programs confer coverage retrospectively. Eligibility is also complicated by income and asset criteria.

For estimating risk from a rate cell, the cell cannot be formed on the basis of insurance status or by income or assets. It can be formed on the basis of family composition, health status, completed education as a proxy for future income, and the likelihood of having coverage from the beginning of the year or baseline (using coverage information available at the end of the year may be a necessary stopgap approach in the short run).

For the regression approach, one can include prior-year covariates as predictors of what will happen in the second year, but these characteristics may not hold in the second period. If a family has some Medicaid coverage in the first year, it is more likely to have coverage in the second year, but that is not guaranteed. Similarly, if a family has low income due to ill health in the first year, it is more likely, but not guaranteed, to have it in the second year.

We emphasize that the risk analysis will be quite different from more traditional burden approaches used for descriptive work or work that adjusts for certain characteristics. Those efforts typically do not deal with cause and effect directly but are merely partial correlation work used for descriptive purposes or to assess differences across groups of social or policy interest.

Data and Estimation Issues

There is a trade-off between the cell-based and multivariate regression approaches when the sample size is not large enough to create crisply

demarcated, homogenous cells. Without enough observations to use cell experience for setting probabilities, we need to say something about how coarse cells compromise the goal that we want and that could be achieved with a larger data set.

Most of what has preceded in this discussion works under three assumptions: (1) there is sufficient information on family structure and income and on the health and details of insurance coverage of each of the members of the family; (2) a health shock is not enough in its own right to change the nature of one’s coverage—in other words, one cannot be eligible for some insurance policy or public program by the nature of the health event (counterexamples include blindness, pregnancy if low income, and renal failure and dialysis); and (3) there are enough sample cases of families with the same family structure, income, coverage, and health status that one can identify equivalent or very nearly equivalent families to form a risk cell sufficient to use the observed distribution as a source of the risk cell specific distribution.

As a practical matter, the assumptions regarding data are not likely to hold with current large-scale data collection efforts (see Chapter 5). Most data sources do not include detailed information on eligibility and coverage provisions for either public or private insurance. Most data sets that would have sufficient information for common risk adjustment methods are small relative to the number of combinations of age, family structure, and health of families that would be needed.

Another concern is that most of the common risk adjusters are statements about expected amounts of spending, not the distribution of that spending, based on small or modest sample sizes, using multiple waves of the data. Thus, any risk classification system needs to be able to handle coarse risk cells for individuals and to find a method for combining data on individuals with varying risks internally within families. This may require the health equivalent of the family composition algorithm used in the calculations of the SPM thresholds. Then the question becomes: Is the family-equivalent health risk a weighted average of the individual risks that reflect measures of how well baseline health predicts subsequent expenditures? How well does such a measure forecast both family means and variances? If one were to address only single-person families, how well does current expected experience also affect the variability in that number?

ISSUES CONSIDERED BUT NOT ADDRESSED IN THE MCER PROPOSED APPROACH

Four issues that the panel considered but decided not to address in its proposed approach for developing an MCER measure are summarized below.

- Defining out-of-pocket medical care spending as some percentage of family income. As discussed in Chapter 2, we decided to rely on multiples of the SPM poverty threshold for assessing the effects of MCER, rather than to measure affordability as a percentage of income and other resources.

- Geographic variation in out-of-pocket medical care spending due to variation in both prices and quantities. The panel has not made any recommendations on geographic variation. The original poverty measure has the same set of thresholds nationwide. The SPM varies the thresholds geographically by differences in housing costs. However, given both the unsettled issue about geographical variation in health expenditures generally and in terms of how payments for Medicare in particular should or do vary, we think a decision to introduce geographic variation into the MCER should wait for results from both the current Institute of Medicine studies on geographic variation and adjustment.10

- Underspending by uninsured and inadequately insured people. As discussed in Chapter 2, this proposed measure looks only at financial risk, not the health risks and broader implications for family well-being of forgone health care as a result of inadequate coverage.

- Predicting the impact of different insurance plans on out-of-pocket medical care spending and total spending. Available data do not support detailed analysis of the effects of various types of insurance coverage on medical spending by families and individuals, although it would be desirable to model these effects so that the impact of changes in coverage could be assessed.

If it were possible to obtain the necessary data on insurance plan details, it would be desirable to model the effects of changes in those details—for example, when premiums rise and to the extent that families have to pay for part or all of their premiums out-of-pocket, their medical care economic burden increases; if there is a move to a high deductible plan, the risk from out-of-pocket expenditures may increase. It would also be desirable to model the effects of changes in copays, coinsurance, and stop-losses (out-of-pocket maxima) on families’ share of costs or limits on covered benefits. When a family’s share declines, other things being equal, its burden and risk would decrease except that members may have incentives to obtain more care of

_______________________

10 IOM Committee on Geographic Adjustment Factors in Medicare Payment (see http://www.iom.edu/Activities/HealthServices/GeographicAdjustments.aspx) and Committee on Geographic Variation in Health Care Spending and Promotion of High-Value Care (see http://www.iom.edu/Activities/HealthServices/GeographicVariation.aspx).

incremental value to them (the incremental value is the positive difference between their marginal out-of-pocket price and the marginal cost of those resources in the health care market). This additional care has some benefit, but must be paid for out-of-pocket or by the insurance pool’s premiums without a compensating change in premiums to that patient or family, or by compensating changes in take-home income/wages.

To incorporate these effects, the sample would need to be partitioned into large insurance categories, such as uninsured, Medicaid, health maintenance organization, private insurance (a few types), Medicare, etc. Under the ACA, it would be useful to distinguish between the various insurance levels (bronze, etc.). For private insurance, if one has details on the actual premiums and coverage provisions, one may standardize by adjusting total spending and out-of-pocket spending from actual to a standard, using the details of insurance to let the coinsurance rate at the time of spending affect the quantity of care obtained and thus out-of-pocket spending. Eventually, one will have to decide how to adjust uninsured spending to what it would have been if the individual were in Medicaid or a standard private policy and other possible policy shifts, such as from a private policy to being uninsured. One can calculate the range of spending for uninsured people either by looking at unadjusted spending in cells of uninsured people, and then adjusting later for their getting a different insurance policy, or by adjusting to a standard policy before grouping cases into cells and predicting adjusted spending, which is then adjusted back from the standard to their coverage in each policy simulation.

USING THE MCER MEASURE FOR POLICY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT

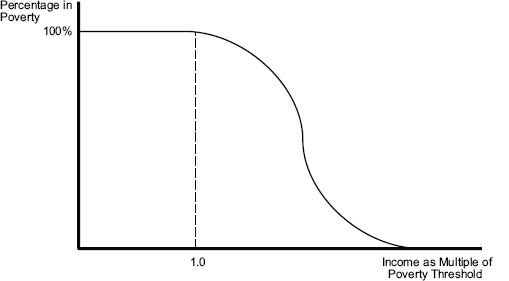

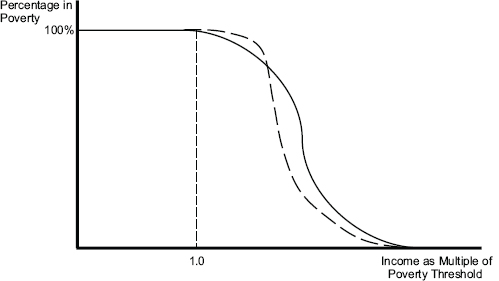

We conclude by illustrating the usefulness of a measure of MCER. Figure 4-1 shows the probability of out-of-pocket medical care spending exceeding the difference between family income and the SPM target threshold as a function of the family’s ratio of income to the SPM target. These probabilities depend on income, health, and the age composition of families; the graph looks like a survival curve if one goes from very low to high income. If there were a set of results from before the ACA was implemented and one after 2014 when it is largely implemented, as Figure 4-2 illustrates, then the area between the pre- and post-curves would become one measure of improvement. The usual caveat about confounded changes in a before-and-after study (for example, the global recession), applies: Both spending and the SPM depend on these external factors. In principle, however, one can simply label each family by its income compared with the SPM target and calculate the probability that out-of-pocket medical care spending will take it below the target. In Figure 4-2, the curved black line is

FIGURE 4-1 The probability of out-of-pocket medical care spending exceeding the difference between family income and the SPM threshold.

SOURCE: Developed by the panel to illustrate the relationship between income and medical care economic risk described in the text.

FIGURE 4-2 The probability of out-of-pocket medical care spending exceeding the difference between family income and the SPM threshold after a shift in out-of-pocket premiums due to incomplete subsidy for health insurance and reduced out-of-pocket spending, as with the transition of the uninsured to coverage under ACA.

SOURCE: Developed by the panel to illustrate the relationship between income and medical care economic risk described in the text.

prior to full implementation of the ACA, and the dashed black line is some time after full implementation. As healthy previously uninsured people (i.e., those without much out-of-pocket spending for health care) in households slightly above the poverty line have their incomes reduced to less than the SPM by premiums post-ACA, the dashed curved line is initially above the black solid curved line. However, the lines soon cross, as less healthy people who are newly insured experience out-of-pocket premiums plus spending for care that is less than their prior out-of-pocket spending, and thus their household incomes are not reduced below the SPM threshold.