State and Regional Innovation Programs

Moderator:

Richard Bendis

Innovation America

Mr. Bendis said that he talked about innovation-based economic development in many places around the world, and northeast Ohio often served as his model. “When you live here in this place I talk about, northeast Ohio, you might take for granted what you have in your own surroundings. So on this panel we’re going to talk about just how remarkable is the work you are doing right here in Cleveland.”

He praised the Third Frontier program in particular as a leading state program which many others are trying to emulate. He said that one quality that distinguishes the Third Frontier and other innovation-based economic development (IBED) organizations in northeast Ohio is the quality of their leadership. “You have world-class leaders running the organizations that every region or state would love to have. So don’t take those people for granted, thank them for being here.” A second outstanding feature of the region, he said, was the effectiveness of its foundations—“a major differential advantage that’s not happening in many other places.”

The global innovation imperative is changing for all of us, Mr. Bendis said, and leading areas are responding to four conditions of great importance. The first is that an area like northeast Ohio is not competing only against the other U.S. states, but also against every other nation in the world. Second is sustained research and development, leveraging both public and private funds. The Third Frontier, he said, has been providing significant funding for this purpose. The third condition is support for innovative SMEs, and the fourth is new innovation partnerships to help bring new products and services to market. He noted that many countries and regions are investing “very substantial resources” for these purposes—“to create, attract, and retain industries in leading sectors.”

LOCATIONAL COMPETITION

Underlying the global imperative, Mr. Bendis said, is the “new locational competition for economic activity. It is apparent that geographical boundaries are no longer relevant in a time of global competition. Basically, you’re competing against everybody, everywhere, every day.” The bar to entry is lower for countries around the world, he said, because innovation is replacing technology as the driver of economies. He recalled the Ohio Edison programs of a quarter-century ago which focused on industries, technologies and products. Innovation, he said, is more focused on services, processes, ways of communicating, partnering, and working together—“not just about creating the next best widget. That’s one of the paradigm shifts.” This new paradigm, he added, includes more public investment and risk taking, developing trust through collaboration, ensuring responsiveness to partners’ missions, and building consensus among all constituents.

Because innovation is collaborative by nature, he said, regional clusters are key ingredients of innovation. He proposed five key components to consider when defining desirable regional assets. These are the economic base, which includes the kinds of products and services produced; entrepreneurship, including the capability to create companies wholly new or from existing firms; talent, including workforce skills and the human capital base; innovation and ideas; and the basic conditions of the region, including location, infrastructure, amenities, factor costs, and natural resources. He said that northeast Ohio already has good collaborative “interaction fields,” including regional clusters and university-industry collaborations, which are needed to power the “innovation ecosystem” and move ideas from the proof of concept stage to the proof of relevance stage. The outputs following the proof of relevance stage include the jobs, new products and services, and commercialization activities that signify wealth creation. He stressed that successful innovation of this kind must be a “triple helix” including education, industry, and government, and that the missions of these three sectors are inseparable.

At the same time, said Mr. Bendis, many states have programs like the Third Frontier, including Pennsylvania and Maryland. The best of these, he said, are both providing early-stage support as seed investors and facilitating collaboration throughout the innovation process. “If you’re going to do this,” he said, “you have to learn how to collaborate, and during the history of IBED, those who have collaborated most effectively have prevailed. I think that what you’ve done in northeast Ohio is to build a good architecture for collaboration. With NorTech, Jumpstart, BioEnterprise, and other intermediaries, you are developing a real innovation ecosystem. Just as importantly, these programs know how to attract other people’s money into the region.”

Mr. Bendis closed by praising the IBED intermediary organizations of northeast Ohio, and reiterating his use of northeast Ohio for audiences elsewhere. “I lead with Cleveland and the organizations represented here as examples of what they need to build if they want to be effective,” he said. “And

one of your strengths is that you understand the need for cooperation. No one organization can do everything that needs to be done. You need to be able to leverage strengths and partner with each other.”

CURRENT TRENDS AND CHALLENGES IN STATE INNOVATION PROGRAMS

Dan Berglund

State Science and Technology Institute (SSTI)

Mr. Berglund began by introducing the State Science and Technology Institute (SSTI), a 15-year-old national nonprofit organization based in Columbus. With 180 members, including state programs, local programs, and universities, SSTI’s mission is to “improve government-industry programs that encourage economic growth through the application of science and technology.” Its founding funders include the Carnegie Corporation, Kauffman Foundation, and Manufacturing Extension Program, with additional support from the Economic Development Administration.

Mr. Berglund said that SSTI believes that there are seven elements required for a vibrant technology-based economy. These include “a good intellectual infrastructure, spillovers of knowledge from universities and networks, a strong physical infrastructure, a technically skilled workforce, sources of capital, a rich entrepreneurial culture, and a desirable quality of life.” The last two assets, he said, are the most difficult to measure. He offered one definition of an entrepreneurial culture: “If you gather all your family and friends in a room and tell them you’re quitting your job to start a company, and if they all applaud, you’re in an entrepreneurial culture.” Good quality of life, he said, “is in eye of beholder.”

Research Parks: Necessary, But Not Sufficient

Why should states spend so much effort building up these seven elements? Mr. Berglund asked. He told the story of going to Kentucky 10 years ago to help the state start its S&T strategic planning process. When he asked state officials what motivated them to act, they pointed to the success of nearby North Carolina in founding Research Triangle Park. They had seen that in 1955, the year before the founding of RTP, both states were poor, with virtually identical per capita incomes at 66 percent of the national level. By 2000, however, North Carolina had moved far ahead of Kentucky, which did not have a research park.

Mr. Berglund said that he later went back to look at the statistics himself, and drew out the chart showing sharply diverging income levels and North Carolina’s relative improvement. “I saw three messages in that chart,” he recalled. “The first was the same one they had seen in Kentucky, that North Carolina had moved far ahead. But the second message was that it took 30 years

to do that; not until 1985 could you see all that effort pay off in higher income. And third, by the year 2000, when the improvement was clear, the state as a whole was still only at 92 percent of national average per capita income. So it did extremely well, but was not successful in translating that success to all areas of the state. This is one of the challenges all of us have in this field.”

Public Approval of S&T

Mr. Berglund looked back at several other trends. When the SSTI was formed, he said, a large part of the mission was to persuade governors of the importance of S&T. “Today there is widespread acceptance across the country, in both parties, of the importance of investing in S&T&I. As an example he cited the new governor of Maine, who ran as Tea Party candidate. “I was sure that if he was elected, the Maine Technology Institute would be eliminated in his first budget. In fact, it received a budget increase. So this continues a trend of last 30 years that political affiliation of the leadership tends not to make a difference for these programs at the state level.”

Mr. Berglund also cited a trend of rising public support for science, technology, and innovation over the past 15 years, but much more recent recognition of the need for commercialization, entrepreneurship, and cluster development. “A number of things have helped correct this,” he said, “including the Rising Storm report, doubling the NIH budget, the creation of Astra to help lobby for these activities.” He said that the Federal budget submitted in February was the most supportive of innovation since SSTI was formed. Fortunately, he said, there was abundant evidence of a political constituency favoring the kinds of investments being made by NIST and EDA. Some 84 percent of Americans believe that more jobs in the future will require math and science skills. In a California state poll, 52 percent said that state policy makers were not making technology and innovation a high enough priority. And 78 percent of Americans think “a national initiative would be effective.”

Mr. Berglund said that support for science was even reaching popular culture. The toy company Mattel had held an online vote for what Barbie’s next career should be, and respondents voted for computer engineer. He said this trend was also seen at ballot boxes. Ohio had renewed the Third Frontier, Maine has passed several bond issues supportive of science, Arizona passed a sales tax, and California passed a $3 billion embryonic stem cell initiative. “So we see a trend of widespread support for science and engineering.”

The Challenge of a Skilled Worker Shortage

Among current challenges, he said, were a predicted shortage of skilled workers and new expectations of higher education. “Teaching students and doing research are no longer the only expectations of higher education,” he said. “The university is now expected to be the engine of economic recovery and growth.” There is also increasing competition from states that have the same

objectives as Ohio. “Ohio has a good chance with the Third Frontier bond issue of leaping over other states,” he said, “but other states are not standing still. Indiana, not a state we typically think of in this area, has spent $238 million in the last decade on TBED, and Michigan has spent $573 million.”

Mr. Berglund concluded with several lessons learned. Paramount is the need for committed high-level leaders who understand that economic impact does not occur quickly and that research does not always generate economic payoffs. Second, action should be based on an understanding of the state’s needs and capabilities. And finally, a successful TBED program must include longterm sustainability, champions from more than one sector, effective management and staff, and an entrepreneurial approach in responding to change.

THE ROLE OF NORTECH: PROMOTING INNOVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Ms. Bagley said she would begin with a brief economic sketch of northeast Ohio and the Cleveland metro area. Among positive indicators, she said, was Cleveland’s ongoing recovery, which ranks 10th among 50 U.S. metro areas, according to the Brookings Institution. In addition, unemployment in northeast Ohio is dropping, with a year-over-year increase of 30,000 jobs in the fourth quarter of 2010.13 According to the Milken Institute, Ohio has increased its number of business startups, growth in capital, and support for academic R&D. From February to June 2010, Cleveland metro led the nation’s 40 largest Metropolitan Statistical Areas in manufacturing job growth.14

This and other is evidence, she said, point to a broader economic transformation that “requires huge shifts in the economy over a long timeframe. It’s really a 20-year process, and we think we’re about halfway through that. The fact that we have this growing innovation ecosystem has become extremely important in continuing this momentum.”

Ms. Bagley said that NorTech works under a regional infrastructure called Advance Northeast Ohio, adopted by the members of the Fund for Our Economic Future and regional business community. This agenda functions on the premise that business growth, talent development, racial and economic inclusion, and government collaboration and efficiency are the key pillars of a stronger regional economy.

![]()

13Source: Team Neo.

14Pittsburgh Today and Fund for Our Economic Future.

A Transition into New, Innovative Products

“Over a year ago, the Fund, NorTech, and other regional partners took Advance Northeast Ohio agenda and structured it in line with a Brookings business plan,” Ms. Bagley said. “There are only three regions in the country with these Brookings plans. The two others are Minneapolis/St. Paul and Seattle/Puget Sound. The strategy is to look at the characteristics and capabilities of the region and set out the things you want to accomplish. The region also started a detailed development initiative, the Partnership for Regional Innovation Services to Manufacturers (PRISM) in partnership with MAGNET. Our key challenge was to accelerate a transition of manufacturing into new innovative products by capitalizing on the existing potentials of the region’s economic ecosystem.”

NorTech, Ms. Bagley said, is a nonprofit technology-based economic development organization (TBED) serving 21 counties in northeast Ohio. Among its funders, a little more than half are foundations, a little less than a quarter are businesses, and about a quarter comes from Federal support. “It’s a partnership that has worked smoothly,” she said.

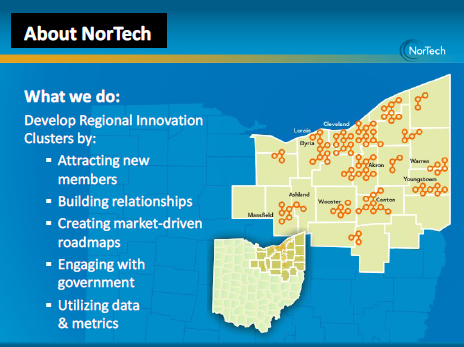

NorTech develops regional innovation clusters by attracting new members, building relationships, creating market-driven roadmaps, engaging with government, and utilizing data and metrics. “The important point,” she said, “is that we develop a model that operationalizes the desire to accelerate emerging industry clusters.” This is done by a partnership of companies, including larger companies, and the goal is to reduce the time required to strengthen a given sector.

Ms. Bagley said that NorTech defines a cluster as an economic ecosystem that is interconnected and geographically bound, and includes the entire value chain of technological innovation: research institutions, materials suppliers, equipment manufacturers, service providers, sub-component manufacturers, product developers. This value chain is facilitated by other participants, especially the media. “Every time we have another news story about flexible electronics, we have another call from a company working in that space. This public exposure is critical, and so are public and private funding, associations, work force development, economic development, and cooperation with all levels of government.”

Clearer Vision Through Roadmaps

One of the key tools, Ms. Bagley said, is a cluster roadmap, which “gives us a clear vision of our assets and where we’re going in a given sector. It puts everybody in the cluster on the same page.” The roadmap process is to (1) identify existing and potential assets, including companies, researchers, and research dollars; (2) understand the global market opportunity in a sector; and (3) benchmark the national (and in some cases international) competition. The cluster members come together and try to describe, based on this information,

their vision for seven years forward. This includes a vision statement, definition of expected jobs, and the leverage “for what’s going to come out of that.”

She said that NorTech’s roadmaps were distinctive in two ways. First, it starts with assessing the global market opportunity. And second, this is followed by a real action plan. “We really think 18 months is a good time frame for the action plan. “We really think 18 months is the limit for an action plan; you can’t go much past that. What are the roles and responsibilities of each member of the cluster, or the cluster as a whole? What’s NorTech’s role? We work out how we do that, and which elements are most important in moving the cluster toward the seven-year goals.”

Partnerships with Governments

A principal feature of NorTech’s work is its engagement with local, state, and Federal governments to seek essential funding that is not otherwise available. “We’ve been very organized in the region around a government strategy that includes all the partners: Jumpstart, BioEnterprise, MAGNET, Team NEO, and NorTech. Basically we defined specific areas for which we need outside funding: advanced energy, innovation entrepreneurism, manufacturers in transition, and business incubation. And of course we need a strong voice in the State of Ohio Third Frontier program as well.”

FIGURE 4 NorTech drives the development of regional innovation clusters.

SOURCE: Rebecca O. Bagley, Presentation at the April 25-26, 2011, National Academies Symposium on “Building the Ohio Innovation Economy.”

Emphasizing the importance of metrics Ms. Bagley, said they are “a critical piece in not only how you talk about the cluster but how you talk about your organization.” NorTech tracks the success of each cluster member. Each member signs an MOU stating what NorTech will provide, with a focus on potential revenue, funding, and collaboration opportunities. Those MOUs are intended to turn into “funded opportunities,” or actual capital attracted, including Federal funding, state funding, private funds, philanthropic, and revenue.

‘Convening, Connecting, Educating’

A final set of priorities for NorTech is to “convene, connect, and educate.” These begin with building relationships and attracting new members. They include education sessions, often by bringing industry experts to conferences to discuss new developments and opportunities in priority areas such as advanced energy and flexible electronics. Typical of this approach is the “synergy sessions with cluster members,” which involves characterizing a market opportunity and identifying the current barriers to that opportunity. An example is the electronic greeting cards, including singing cards, being marketed by American Greetings. This opportunity fits with the existing flexible electronics cluster, including flexible batteries, flexible LCDs, and other technologies that might produce new products for American Greetings markets.

In reviewing the distribution of the region’s specific clusters, Ms. Bagley showed a map portraying about 400 energy-related companies that had self-registered on the NorTech website. The energy space for northeast Ohio includes 11 “areas of opportunity,” with four of them targeted for the first roadmaps: waste & biomass to energy, energy storage, electric transport, and smart grid. A priority for NorTech is to help firms in Northeast Ohio connect with others elsewhere, creating, for example, a node for solar innovation in the Toledo area. The region also has significant assets in fuel cells, which we are trying to connect with others. For offshore wind energy, NorTech’s partners include the Cleveland Foundation and the Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation (LEEDCo). The goal is to develop the first fresh water wind farm in Lake Erie. This project is being led by LEEDCo. “The reason we care about offshore wind,” she said, “is not only the deployment and transformation of our energy sector, but the jobs and economic impact this sector can have on Northeast Ohio.”

NorTech is also developing a “FlexMatters” cluster whose vision is “to emerge as a leading producer of flexible electronics sold globally,” and specifically to “attract customers, investors, talent, and commercialization partners from around the world.” FlexMatters’ seven-year goal is to raise $100 million in capital from 100 cluster organizations and to produce 1,500 jobs generating a payroll of $75 million.

Ms. Bagley concluded by saying that the first four roadmaps would be finished within a few months. She said the region could emerge as a leading

global producer of flexible electronics. “We’ve been working in this area for a very long time, and between the University of Akron and Kent State University, we have a critical mass in research assets. Moreover, we have companies that make products and the various markets in flexible electronics. If we can capitalize on that and make the cluster as interconnected and ‘sticky’ as possible over the next three years, we can be known internationally as a premier focus of innovation in flexible electronics. This will take a lot of focus from the community, and buy-in from the stakeholders, but the markets are already forming.”

DISCUSSION

Dr. Singerman commented that as a long-term observer of the region, he saw its strategy as distinctive in several ways. First was the critical role played by the philanthropic community in organizing and energizing the economic development community. He said that only a few other places, including Pittsburgh with the Heinz Foundation and St. Louis with the Danforth Foundation, had benefited from this degree of philanthropic leadership. The region had also gained visibility through its programs with the Brookings Institution and the Center for American Progress, and now the National Academies. “This is not an accident,” he said. “It’s a result of a lot of hard work. Also, it’s no accident that the President came to Cleveland a month ago, and I’m sure the newspaper articles and phone calls had incalculable value.”

Mr. Bendis said that regional strengths and visibility run in cycles, and that northeast Ohio was in an up-cycle. “This is your day, northeast Ohio. Enjoy it, but don’t rest on your laurels. It takes continual renewal and reinvestment to maintain the leadership position you now have. Others will study you and emulate what you are doing.”

Dr. Wessner asked whether there were visible gaps in the model, and whether it was sustainable as presently formed. Mr. Berglund said that SSTI, his organization, had a high opinion of the region, and that it had selected Cleveland for its annual conference several years previously. Those locations are chosen because they are “select places we think have a good story to tell, and a place where people will learn from.”

Good Communication Among NGOs

A questioner noted that with several NGOs working in the same region, it would be helpful to understand the distinction between their missions. Mr. Berglund agreed, saying that good communication and personal relationships among the organizations had much to do with the region’s success. Some other regions, he said, had had difficulties in this respect. In Pennsylvania and New York, he said, new administrations had seen what appeared to be redundant development organizations and proposed replacing them with block grants for the regions. “Part of the reason why that happened in those states,” he said, “is

that the development organizations didn’t play together as well there as they do here.”

Mr. Bendis responded to that issue by mentioning the “three C’s” that can cause conflict among organizations. One, who gets the most cash; two, who’s in control, and of what; and three, who is getting the credit for positive results. “Some symptoms of these problems can be mission creep from one organization to another; funders starting to balk at different organizations lining up at the door for similar missions, rather than coming in together; and the cash barrier that challenges not-for-profits at the state and regional levels. “One of the greatest challenges is that all the NGOs have to demonstrate that they are doing an effective job on providing a return on investment for stakeholders in order to keep them happy.”