Gretchen Kalonji UNESCO, France

I am going to offer you a very brief overview of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). I will give some examples of current activities that have to do with the challenges of data access and sharing, particularly in the developing world, and then proceed with some ideas about new opportunities and new directions that we might pursue in hopes of getting feedback from you and even perhaps forging new collaborations.

UNESCO was founded in 1949, and has an extraordinarily broad mandate covering education, science, and culture; communications and information; and ethics and philosophy. Such a broad mandate could be seen as a disadvantage, but within the context of the challenges that we are addressing at this meeting today, I hope to show you why this mandate may in fact be a very useful thing.

The organization has some strong existing programs within the natural sciences sector, in particular, the well-known Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission and the International Hydrological Program. Both have been around for 50 or so years. We also have the ecological sciences with the Man and the Biosphere Program and the International Geosciences Program. What is perhaps less well known is our strong focus on indigenous knowledge and science policy. Science policy is one of our largest areas.

We are headquartered in Paris, but have science offices in Jakarta, Nairobi, Montevideo, Venice, and Cairo. We have science officers in about 53 UNESCO offices around the world. It is a strong, geographically distributed network with people on the ground actually working on projects.

UNESCO has a number of affiliated institutions, including our Category One Centers. The best known to this community is probably the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, but we also have an international hydrological education program in Delft, which is the world’s largest postgraduate freshwater program, with 80 percent of the students coming from the developing world. The Academy of Sciences for the Developing World, TWAS, is also a UNESCO institution.

UNESCO also has what are called Category Two Centers, which are affiliated research centers established by our member states within a particular country and funded by that country. The country agrees that they will take on an international responsibility for a particular topic (e.g., water-based disasters, including one in Japan called ICHARM [International Center for Water Hazard]). We have about 22 of those in the sciences. Most are in water, and there are four new ones being established in Africa. Lastly, we have UNESCO Chairs around the world, which are appointed in a competitive process, and they are another wonderful resource for UNESCO.

One of the things that we have that is particularly important for the challenges we are discussing today are the extraordinary and very well-known World Heritage sites. They are designated for either cultural value, natural value, or both. In addition to the World Heritage sites, we have the biosphere reserves and the newly emerging geoparks, which are very popular in some countries, particularly China. Those are areas where a combination of research and education and community economic development can take place in an integrated manner.

We also have a network of affiliated partners. CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research,1

_____________________

was in fact created through UNESCO, and we continue to work very closely with them on issues such as digital access in Africa and physics education for teachers in Africa. The International Council for Science (ICSU) predates us but is a very close partner institution. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry is another partner. We are working very closely with them on the International Year of Chemistry. One of the things that is perhaps less well understood about UNESCO is the very close relationships we have with our member states. We are unique within the United Nations specialized agencies and programs in that we actually work in the same building in Paris as the permanent delegations from the member states, which enables a very close working relationship on concrete projects. We also have a structure that is unique within the UN system. The national commissions for UNESCO bring civil society together to help set directions for the organization. These commissions are more or less active. Korea, for example, has 600 people working on education, science, and culture, and UNESCO has become a household word there.

Lastly, we have perceived political neutrality. What that means is that we can convene discussions about topics that are quite thorny and have our 193 member states from around the world come together and discuss them in an amicable manner.

On the other hand, we could have a more strategic focus. We need to have a better working system of all of these various parts and partners; we need to work better with other UN agencies, the private sector, and other sectors of society; and we need to enhance our visibility.

Given these strengths and weaknesses, UNESCO’s science agenda should prioritize three things. First, we should help tackle problems that intrinsically require international cooperation and provide services for member states in that regard. Second, we should build on our original mandate. UNESCO was created with the slogan of building peace in the minds of men and women. We focus on those areas in which the science agenda interacts very closely with the issue of conflict prevention and conflict resolution. The broader agenda of peace is very dear to our hearts. I cite a couple of examples here. One is our work on transboundary aquifers, which I am going to talk about later in terms of large-scale data challenges. The other one is a fascinating effort called SESAME (International Center for Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East), which brings together scientists throughout the Middle East. It is a very important project in that it is putting together a synchrotron in Jordan and bringing together a scientific community from throughout the disciplines that can use this light source. It is an extraordinary example of scientists from a region with a huge amount of tension actually working together. Iranians, Israelis, Palestinians, Turkish, and so on are all working on the same large-scale science project.

Lastly, perhaps the bulk of our activity falls into serving the member states. We are international civil servants. We need to do the best job possible to help our member states reach their own goals for building scientific, technological, and innovation capacity in order to address poverty eradication and also provide the scientific basis for the solutions that are being proposed. Of course, we should continue to prioritize work in those areas where we have a lot of expertise, such as water.

At UNESCO, we have a unique view regarding the science and the development agendas. We have a very people-centered approach—an approach that is based on empowerment, ethics, and respect for local knowledge, but also our conviction that the ability to contribute to global challenges and the opportunities to do so are in fact fundamental human rights.

Since I joined UNESCO, we have melded our activities into a new strategic plan to be approved by our executive board next month. We have clustered our activities into two main areas, which I will talk about to show how the data challenges map onto some of these activities.

One area is strengthening science, technology, and innovation ecosystems. Societies have to have good policy, and we put an enormous amount of attention into that effort, particularly in Africa. Some of the symposium speakers have stressed that universities are really the heart of healthy technological innovation ecosystems. We have a big focus on higher education in the developing world, and on mobilizing the popular understanding and support for science, such as science for parliamentarians, science journalism, and working with science museums, as well as programs that enhance participation of indigenous people. To summarize, this cluster focuses on

• Promoting science, technology, and innovation (STI) policies and access to knowledge;

• Building capacities in basic sciences and engineering, including through strengthening higher education systems; and

• Mobilizing broad-based societal participation in STI.

The second cluster is mobilizing science for sustainability. This is an activity where large-scale scientific communities come together to set a collective scientific agenda.

I want to discuss a couple of examples for how these large-scale data issues become the actual work of our UNESCO family. In freshwater, UNESCO has the International Hydrological Program, which is an intergovernmental effort. Each nation has its own committee that works on setting a collective agenda in the area of freshwater. Then together they develop a 6-year plan that they modify over time. This is just one of the examples in which a community of hydrologists working together is trying to assemble the kind of data that we need. An example of the success of their work is in the transboundary aquifer in parts of the world, including Africa.

In this kind of an effort, UNESCO plays a coordinating and somewhat catalytic role, but basically there are multiples of hundreds of hydrologists around the world working on a common agenda. This is very important for avoiding conflict. Our connections with the UN system means that the scientists can work with the legal people in the United Nations and the diplomatic representatives to help forge the law in the general assembly concerning the equitable sharing of transboundary aquifers.

In the current work plan for freshwater intergovernmental science programs, there is a big emphasis on education, sustainability, basic sciences, and climate change. There are also cross-cutting programs, such as networks of hydrologists who work on a regional and global basis sharing data for hydrological research. For example, there is a Nile River basin group that brings together the scientists who are dealing with the Nile River water issues.

Another example of data sharing that is qualitatively different is the Man and the Biosphere Program. In this program, there are 564 sites in 109 countries. These sites are proposed by each country. There is an intergovernmental body that decides whether it can become a biosphere reserve. The interesting thing about the biosphere reserves is that, unlike the World Heritage sites, they involve a region that is protected because of biological diversity, but humans also live there. There is also a buffer zone surrounding the core region, and an extended zone. What that means is that activities such as mining, tourism, and farming are not forbidden. It gives scientists the opportunity to have some very vibrant case studies of the international balance between biodiversity conservation and economic development and livelihoods for local communities.

Let me briefly touch upon some other areas. UNESCO’s science policy activities range from international, like the World Science Report and the World Engineering Report, to regional and country-based policy support. Twenty-two countries in Africa are working with us right now on their science policies.

In the geological sciences, there are many examples in which the global change research community has been working together with a broader geological community, particularly the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), on getting access to and combining and sharing geological information from a variety of sources, including paper-based sources. It is a very exciting time now for the biodiversity community, too, and an intergovernmental platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services has been discussed. The biodiversity analog of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will undertake a very large-scale effort to promote access to data in the area of biodiversity. This is particularly exciting because of the newly created Nagoya Protocol for Access and Benefit Sharing.

There are three qualitative areas to which I believe UNESCO contributes. First, it helps strengthen the capacity of member states to engage in data-intensive science. Second, it provides platforms for more effective community engagement. Lastly, UNESCO enhances awareness of the value of freely sharing scientific data.

UNESCO could, if it is of interest to other partners to work with us, potentially host a meeting in Paris with our member states about the same topic, because they are the direct representatives to the government. They are the ones who need to hear the speeches like the one from Professor Yang about how wonderful it was for China to make data freely accessible.

My second idea is to incorporate within our existing efforts on strengthening higher education a collaboration on developing capacity in data-intensive science in partner universities, especially in Africa. It should be very straightforward to integrate awareness-raising activities into some of our existing efforts, like our work with ICSU in preparation for the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), or programs on science for parliamentarians, or our work on policy.

Lastly, I am very excited about the Intergovernmental Science Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). It seems very likely that UNESCO, together with the UN Environment Programme and maybe another agency, will be taking the lead as the institutional cohost for IPBES. I would be interested in brainstorming with individuals or organizations about this extraordinary opportunity.

26. International Scientific Organizations: Views and Examples

Bengt Gustafsson Uppsala University, Sweden ICSU Committee on Freedom and Responsibility in the Conduct of Science

I will begin with some historical remarks. History provides an enormous data bank, which is also useful when we discuss the accessibility of data banks in contemporary research. By starting the discussion by referring to the development in Europe some four to five hundred years ago, we find scientists quite often keeping their truths between themselves, and even sending cryptographic messages to each other to prevent others from reading or understanding. The interesting counter-examples in the early seventeenth century were the new artisans, the small factories, and the people developing technology for mining. They were open-minded, and symbolized modernity.

Openness was from the very beginning connected to the idea of progress—progress in arts and in building a new society. That was clear and strongly brought forward by Francis Bacon. Let me cite from an account of this by William Eamon in the Minerva article, From the Secrets of Nature to Public Knowledge: The Origins of the Concept of Openness in Science: “One of the lasting effects of the influence of Bacon’s philosophy was the establishment of a new model of the scientific research worker as one dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge for the public good. No longer was science to exist merely for the pleasure and illumination of a few minds; it was to be used for the advancement of commonwealth in general. This new demand required that more knowledge be shared, both within the scientific community and with society at large.”2

However, this was not the beginning; traditions along these lines existed before the Renaissance in Europe. But the ideas from Bacon’s time form the ideological tradition in which we scientists still live and work. This was also the spirit in which the Royal Society was formed in 1660, in fact, directly inspired by Bacon and his writing, and that also pursued the idea of transmitting publicly the findings by its Philosophical Transactions. There were many academies formed on this model. One was my own academy, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, in the following century. The aim was to develop and spread knowledge in mathematics, natural sciences, economy, trade, useful arts, and manufacturing. There was also the idea of publishing descriptions of research achievements and creating a pregnant almanac containing advice for farmers and others, which was the second book printed in Swedish during more than 100 years. Only the Bible was read more than the Academy almanac.

These ideas are important cornerstones in the foundation of all academies still and also for the International Council for Science (ICSU), which has about 100 national members, most of them academies, as well as some international scientific unions. Since the 1930s, ICSU has built its activity on the Principle of the Universality of Science (Universality Principle). This principle is fundamental to scientific progress. According to the 5th statute of ICSU, the principle involves freedom of movement, association, expression, and communication with scientists, as well as equitable access to data, information, and research materials. In pursuing its objectives for the rights and responsibilities of scientists, ICSU actively upholds this principle and, in so doing, opposes any discrimination on the basis of such factors as ethnic origin, religion, citizenship, language, political stance, gender, sexual orientation, or age. ICSU states that it shall not accept disruption of its own activities by statements or reactions that intentionally or otherwise prevent the application of this principle.

What can we do to uphold this principle in reality? ICSU has taken a number of steps for this, such as

_____________________

2 Eamon, W (1985). From the Secrets of Nature to Public Knowledge: The Origins of the Concept of Openness in Science. Minerva 23, pp. 321-347.

establishing committees, including its current Committee on Freedom and Responsibility in the Conduct of Science (CFRS). It is clear from the name of this committee that it has wide objectives, reflecting the view that the freedom advocated in the Universality Principle should also require that important responsibilities are taken by the scientific community relative to the society. In addition to this committee, ICSU has also taken other initiatives, which are directed more particularly toward securing data distribution and data accessibility, such as initiating a Strategic Coordinating Committee on Information and Data, looking at the interaction of the World Data System, the Committee on Data for Science and Technology (CODATA), and other ICSU data- and information-related activities. ICSU has also cooperated with other organizations in forming an International Network for the Availability of Scientific Publications.

The CFRS discusses and takes stands against breaches of the Universality Principle. This is often done in collaboration with several other organizations, in particular, the members of ICSU. Another important collaborator is the International Human Rights Network of Academies and Scholarly Societies. The CFRS advises ICSU and ICSU members on related matters and helps arrange conferences and workshops on issues of responsibility and integrity of science. In doing so, it is important for the committee to also try to reach conclusions; after such workshops and conferences, conclusions are published as statements or advisory notes. Some recent examples, in addition to this workshop, is a workshop on access and benefit sharing of genetic resources held in Berne in June 2011, as well as one on private sector–academia interaction in November 2011 in Sigtuna, Sweden. Other workshops are planned on science policy advice, science and antiscience, and science in contemporary wars. All these workshops must be truly international and will have a focus on the balance of responsibility and freedom in science.

Now, turning more particularly toward the question of access to scientific data, it must be stressed that the present situation, although improving, is far from satisfactory. As Paul Uhlir pointed out in a 2010 essay in the CODATA Data Science Journal, there are still “information gulags,” that is, large numbers of data resources in dark repositories; “intellectual straitjackets,” exclusive property protection of data when not needed; as well as “memory holes,” meaning that data once collected are often later destroyed or not conserved properly3. Existing data are most often not properly archived. Even quite important data are not maintained. Early National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) data are examples of this.

Let me now focus on my own field, astronomy, and provide several examples to show the progress in openness, with a more historical twist than that of the stimulating presentation by Željko Ivezić. A famous example of secrecy in science is the behavior of Galileo Galilei when he summarized his pioneering telescopic studies of the planet Saturn in the early 1610s. He did not interpret what he saw as a ring system, since there seemed to be two bodies on either side of the planet, or possibly “ears” on the planet. Yet, to claim his discovery in spite of the uncertain interpretation, he used an anagram (when deciphered indicating that the planet “had triple form”) as a form of commitment scheme. Not until several decades later, Christian Huygens correctly identified the ring system and announced its existence.

Twice a century, Venus passes across the solar disk; the first detailed European observations of this phenomenon were made in 1639. James Gregory next proposed that a method could be developed to find the distance to the sun by timing exactly when Venus enters the solar disk and when it leaves the disk. If that is done from several places on Earth, the distance to the sun could be determined accurately. Edmond Halley proposed that astronomers should observe the Venus transits systematically next time, which happened to be after his death in 1742. Astronomers traveled to various parts of the world to measure the transits of Venus accurately. The first passage was in 1761. There were even measurements made from a

_____________________

3 Uhlir, P. (2010, October 7). Information Gulags, Intellectual Straightjackets, and Memory Holes: Three Principles to Guide the Preservation of Scientific Data, CODATA. Data Science Journal, 9.

naval frigate while fighting pirates in the Mediterranean. The data were then assembled, shared among a network of astronomers, and made common.

During the event 8 years later, astronomers were even better spread across the globe, including a British expedition on Tahiti where young James Cook was sent with his vessel to carry out the observations. His observations turned out to be rather poor. The excuse given by Cook was that the quadrant was robbed by a local chief and dismantled, and then only provisionally mended. On his way back, however, he discovered some new regions of the earth and reported this back to the admiralty, and they forgave him explicitly for his bad observations. The data were assembled and discussed among the astronomers, because they did not have the quality expected—the distance calculated by Jérôme Lalande in Paris was 153 million kilometers plus 1 million kilometers, which was not as good as they had hoped for. This very problem of coordinating all observations and minimizing the errors led to requirements for further openness.

Another great international project from the following century was the great star map, Carte du Ciel, where 22 observatories joined in constructing rather similar telescopes, which together exposed 22,000 photographic glass plates with 4.6 million stars to be measured and printed. Many people, including non-expert women, were engaged in these activities. The whole result was published in 254 volumes. Again, the need to reach the goal required wide international collaboration, and to achieve optimal quality, openness was necessary. This experience that such ventures must be carried out in common, not only to make the heavy workload possible but also to achieve an optimal analysis of the data, demonstrated to the astronomy community the importance of sharing data.

In contemporary astronomy we find this intimate collaboration taking place not only in discussing the data or sharing data but also in the very setting up of projects and determining how to analyze the data, how to release them, how to publicize them, and how to provide assistance so as to allow as many people as possible to contribute. At many of the largest international telescope facilities, financed by consortia with universities or states as members, nonmember astronomers may take part, and in some cases even be principal investigators (PIs) on projects. At least in principle, only excellence of the project proposal matters. Finally, in most cases, all data are made fully public after about 1 year.

We can compare this situation with CERN, the European high-energy physics laboratory at Geneva. Nonmember state PIs work there and are playing important roles. CERN also runs an open fellowship program, to which scientists from all over the world are encouraged to come and team up with others. Some primary data are available from earlier experiments, but the recent ones, including the Large Hadron Collider experiments, will probably not be available publicly, just because they are so extensive. It is very hard to interpret them without being a member of the experimental group. In this case the enormous database of primary data may still be closed.

Astronomers produced a data manifesto 5 years ago, which was later adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). It starts with this declaration: “We, the global community of astronomy, aspire to the following guidelines for managing astronomical data, believing that these guidelines would maximize the rate and cost effectiveness of science discovery.”4 Relevant guidelines include: “All significant tables and images published in journals should appear in astronomical data centers. All data obtained with publicly funded observatories should after proprietary periods be placed in public domain. In any new major astronomical construction project, the data processing, storage, migration and management requirements should be built in at an early stage in the project and budgeted along with other parts of the project. Astronomers in all countries should have the same access to astronomical data and information. Legacy astronomical data can be valuable and high-priority legacy data should be preserved

_____________________

4 Available at http://www.atnf.csiro.au/people/rnorris/papers/manifesto.pdf

and stored in digital form in the data centers. IAU should work with other international organizations to achieve our common goals and learn from our colleagues in other fields.” Legacy astronomical data refers to older data. For instance, the glass plates mentioned above can be valuable and even high-priority legacy data, and they should therefore be preserved and stored in digital form in the data centers.

Implementing such a manifesto is, of course, a major undertaking. One important initiative along these lines is the International Virtual Observatory Alliance, which is a worldwide organization of national members, which tries to make all astronomical observational data in various wavelength bands from various instruments available publicly. Several international astronomical data centers also play a great role in these endeavors.

Such efforts to promote openness are not only for generosity. There have been studies showing that the open data policy of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) has increased the number of publications based on HST data by a factor of 3, and that the earlier satellite telescope International Ultraviolet Explorer has increased the number of publications based on those data by a factor of 5. Another important issue on openness is open-access publications. Most astronomy papers can now be accessed freely via a preprint database or archive (Smithsonian/NASA Astrophysics Data System), and most major journals accept this way of prepublication.

Let me also comment on the problem of overcoming the digital divide. There are several concrete examples of attempts within the scientific communities in particular fields to bridge the gap between the developed and the developing world in this respect. In astronomy, this bridging has partly been driven by the important fact that many of the best astronomical sites are situated in developing countries. The IAU has recently established an office for astronomy development in the developing countries at the South African Astronomical Observatory. The experience at the International Science Programs at Uppsala University, which has been actively bridging between university science departments in the developing world and in the Nordic countries for 50 years, shows that much can be done to diminish the digital divide with patience and consistency.

No doubt, astronomy is a simple example with a long tradition of international collaboration and openness. Astronomers have realized that international collaboration is necessary, because the universe is large and rich in a multitude of various phenomena. Astronomy has limited economic impact and interest and few security restrictions. And it is mainly motivated by the interest of the public, which after all have to pay for it, and is why openness is necessary. So, astronomy is a simple case. Nevertheless, we may learn from it. There is a full chain of openness aspects in the scientific process to be considered. Can we be open in project planning, letting people team up whenever they want in the process? Can we be open in planning our big investments, building our telescopes, our accelerators, and our big projects? Can we be open in data analysis even before we have published the data, and open in data use too? I think so. Our science will benefit from openness in all these respects.

We can learn from history that much of science is primarily not driven by scientists, but by society. However, almost all science is also science driven. There are good reasons, both from a scientific point of view and from a societal one, for promoting better science by being open. We also can learn from examples of several of the presentations during this symposium that individuals matter.

By opening up internationally together, we actually can provide something even more important than pure science to the world—namely, demonstrate that together we can do very difficult things. Previously, we have mostly demonstrated this by way of war operations in big international collaborations, but here we can do it with more lasting value. Can we afford to continue losing more than half of all human capacity that would wish and be able to contribute important scientific achievements? Of course not. That is the basic motivation for all these endeavors.

27. Improving Data Access and Use for Sustainable Development in the South

Daniel Schaffer Academy of Sciences for the Developing World, Italy

I am speaking on behalf of TWAS, the Academy of Sciences for the Developing World. I will explain what TWAS is, in brief, later in the presentation. At the outset, my talk will focus on both scientific information and scientific data. I will speak about key issues raised during this 2-day symposium, but with a TWAS twist and a particular focus on broad-based problems faced by scientists in the developing world who are seeking to access scientific information and scientific data.

A world-class technical library can be found on the campus of the Abdus Salam International Center for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, where TWAS is also located. When ICTP was created in the 1960s, the library was the centerpiece of the enterprise. Scientists from across the developing world would come to ICTP for the library, since it was unlikely they could get the information at institutions in their home countries. Of course, they would also come to participate in ICTP’s research and training activities.

The library is still there, but scientists can now often access much of the library’s material from anywhere. The shift that has taken place at ICTP, I believe, is symbolic of the broad changes that have occurred in scientific information and data access across the world.

My presentation will be framed by the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that everyone has the right to share in scientific advancement and its benefits. The members of the United Nations signed this declaration in 1947. To that end, there is a long-standing principled foundation to the quest for free and open access to information and data.

As we all know, the number of scholarly and scientific publications are increasing at a rapid rate. It is estimated that there are 25,000 to 50,000 scholarly publications worldwide. Some 2.5 million scholarly articles are published each year. It is estimated that the output is doubling every 15 years. Scientific information is experiencing its greatest transformation since the advent of the printing press more than five centuries ago, and what is true of scientific information is equally true of scientific data. In 2010 it is estimated that the world generated 1,250 exabytes of data. If you placed that data inside a conventional compact disk (CD) and you stacked those CDs one atop another, the stack would rise 3.75 million kilometers, a distance equal to five times to the moon and back. We are generating additional information at such a rapid pace, this year alone we will be producing 1,800 exabytes of data. That means there would be several more stacks of CDs rising to incredible heights.

Some of the problems in communications exist despite the enormous flow of information and data, and some exist because of the endless flow of information and data. For example, there are still some fundamental obstacles that stand in the way of the use, interpretation, and exchange of information and data. Many of these challenges have been mentioned over the course of the past day and a half. Some are universal. The data deluge itself presents an enormous data management problem. Security issues exist at both national and international levels. There are also privacy issues, particularly related to data on public health and medical research. What has not been mentioned extensively here is the reluctance to share data. As we all know, the international scientific community is based on competition and individual accomplishment. That often leads to reluctance on the part of scientists to share data.

Some of the challenges are particular to the developing world. As we heard in the first session today, in poor countries, there is often poor Internet access, limited access to computers themselves, and low bandwidth. It is much less of a problem than it was 10 or even 5 years ago, but it still persists in parts of

the developing world. There is also limited access to scientific literature. Historically this has been due to the cost of subscriptions, but we have shifted the burden from institutions to individuals through open access, which has admittedly been an important engine for the spread of scientific information and advances in scientific capacity in the developing world. Nevertheless, open access presents some problems for individual scientists, particularly young scientists.

Last year, TWAS held a conference in Egypt in partnership with the New Alexandria Library on scientific publications. Many of the young scientists who participated in the conference complained about open access because they simply did not have the resources to participate. Charges of $1,000–$1,500 U.S. dollars in author fees to publish in an open-access journal are beyond their means. Indeed it exceeds their yearly salaries. As a result, they do have problems with contributing to and accessing open-access materials, despite all of the benefits that open access provides.

Additionally, there is inadequate training for gathering and interpreting data, poorly equipped laboratories, excessive teaching responsibilities that distract researchers from their research, limited career opportunities that dampen enthusiasm for research, and a general lack of funding. TWAS did a survey about 2 years ago asking young scientists in the developing world, particularly poorer countries in the South, what their research environment was like and what kinds of issues they confronted. We received an e-mail from one scientist in Nigeria, where she had a list of problems with which we are all familiar. I would like to point to the opening and closing paragraphs of her e-mail to highlight the realities those scientists in her circumstances face. She wrote: “For the past 3 hours, I have been trying to reply to your email, but the power has been going off and on every minute.” And the last sentence reads: “I cut my discussion short because I need to send this message now before the power goes off.” That is the reality that many young scientists face in poor developing countries.

Despite these challenges, there are some—in fact, many—encouraging developments. Two reports published recently indicated that the trends are positive for capacity building and access to scientific publications and scientific data collection in the developing world. These reports are the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Science Report5, published in 2010, and the Royal Society’s Knowledge, Networks and Nations6, published in March 2011.

The UNESCO report indicated that over the past decade, there has been a substantial increase (from 30 percent in 2002 to 38 percent today) in the number of publications by scientists from the South published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Yet much of this growth has been due to a very small number of countries. According to surveys done by TWAS, six countries (China, India, South Korea, Brazil, Taiwan, and Turkey) in the global South are responsible for 75 percent of the publications that are being produced in the developing world.

We should note that some of these countries are no longer considered developing (e.g., China is both a developing and a developed country, and South Korea is defined as a high-income developed country in most economic surveys and reports). China, in fact, is now playing a role in the South similar to that played by the United States in the world, in the sense that it is producing 25 percent to 30 percent of all the journal publications in the developing world.

According to the Royal Society’s Knowledge, Networks and Nations7, China is on course to overtake the United States in scientific output, possibly as soon as 2013, which is far earlier than expected. Leaving aside the question of impact and overall quality, for sheer quantity, within the next 2 or 3 years, Chinese

_____________________

5 Available at http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/science-technology/prospective-studies/unesco-science-report/

6 Available at http://royalsociety.org/policy/projects/knowledge-networks-nations/report/

7 Available at http://royalsociety.org/policy/projects/knowledge-networks-nations/report/

scientists will likely outpace scientists in the United States in the number of scientific publications they publish.

So, on one side of the spectrum, we have six “developing” countries that are responsible for three-quarters of scientific publications in the developing world. On the other side of the spectrum, we have a group of 80 developing countries that produce very small quantities of scientific information. These countries are home to 1.6 billion people, 25 percent of the world’s population. They are responsible for less than 1 percent of the world’s scientific publications. Many of these countries are in sub-Saharan Africa.

We have heard examples of superior science being done in the South, and this is undoubtedly true, but the aggregate figures indicate that there is also a growing gap in scientific publications between countries such as China and India, which are progressing rapidly, and others that are lagging farther and farther behind. From TWAS’s perspective, one of the key questions about scientific information and scientific data is, How do you deal with these two divergent trends—a narrowing North-South divide that is being matched by a widening South-South divide?

Let me spend a few minutes now talking about TWAS, the Academy of Sciences for the Developing World. Abdus Salam, the Nobel laureate from Pakistan, founded TWAS in 1983 in Trieste, Italy. The secretary general of the United Nations inaugurated the Academy in 1985. It operates under the administrative umbrella of UNESCO. It began with 40 members. It now has 995 members from nearly 100 developing countries: 853 fellows in 74 countries in the South, 142 associate fellows in 17 countries in the North. Fifteen Nobel laureates are TWAS members.

Some of the Academy members may be familiar to you. There is Atta-ur-Rahman, who spoke to the participants at this meeting yesterday from Pakistan via cyberspace. There is Mohamed Hassan, who just stepped down as the TWAS executive director, and the new executive director who was previously on the council, Romain Murenzi. He more recently worked with the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C.

The objectives of TWAS are to:

• Promote excellence in scientific research in developing countries;

• Strengthen South-South collaboration;

• Encourage South-North cooperation between individuals and centers of excellence;

• Respond to needs of young scientists working under unfavorable conditions; and

• Engage in the dissemination of scientific information and sharing of innovative experiences.

Our activities include sponsoring a South-South postgraduate and postdoctoral training fellowship program that we conduct in partnership with such large and increasingly successful developing countries as Brazil, China, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, and Thailand. We award 175 fellowships per year. Developing countries provide the funding for local expenses and tuition. TWAS provides the funding for transportation to enable these young scientists from the poor developing countries to go to centers of excellence and universities in the host countries. We also have a research grants program for individual scientists, comprising relatively small grants of $15,000, largely used for purchasing equipment and supplies. Despite their modest size, these grants have a great deal of credibility, and they are well known among scientists in the developing world.

We also support institutions. We have a grants program for research groups in poor developing countries. We provide the groups with $30,000 a year over a 3-year period (subject to an annual performance review). These groups have shown much fortitude, ingenuity, and progress in doing research under very

difficult conditions, and this money can make a big difference in the quality of their research going forward.

Furthermore, in recognition of the growing capacity of scientific expertise and excellence in the South, we have established, over the course of the past decades, five regional offices. The goal is to develop these regional offices into mini TWAS’s that can address within their own regions many of the same issues that TWAS does across the South.

Given what I have said about TWAS, and given the trend toward a widening South-South gap in scientific capacity, how can we manage the growth of data and information for the benefit of all developing countries? It is a key question for TWAS and a key question for most of the members of this audience.

I am going to make a number of recommendations. The good news is these are not radically new ideas. Many of the recommendations have been discussed here. In fact, the recommendations are largely in line with many of the activities, programs, and initiatives that you are involved in. The recommendations also represent a strategy, in the TWAS context, to make them more encompassing so that they do not focus solely on successful developing countries at the expense of developing countries that are not fully participating in international science. I therefore support the following recommendations:

• Access and strategies that provide reduced rates for journals for scientists from poor developing countries. There are a number of initiatives already in play, and they should be supported by institutions like TWAS and institutions that you belong to in order to expand their impact to include the 80 science-poor countries that TWAS has identified.

• Efforts to expand bandwidth and information and communication technology infrastructure.

• Greater participation of scientists in developing countries in international projects. This is happening, but it needs to happen on a broader and more extensive scale across the developing world.

• Strategies for improving the management of indigenous databases.

• The quality and availability of journals and data information produced in the South. The International Network for the Availability of Scientific Publications (INASP) was mentioned in several of the talks. There is also SciDev.Net, which provides extensive news coverage about science and development in the developing world.

• South-South data collection and exchange. Again, there are a growing number of examples, such as the Chinese-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite Program.

• Regional repositories and mirrors in the South. Examples include the National Science Information Center in Karachi and the New Alexandria Library in Egypt.

• More expansive global discussions on data management and use, incorporating the South’s viewpoint not just on issues related to training for data acquisition and interpretation, but also on issues related to broader policy and ethical concerns. In fact, in doing reading for this presentation, I noticed that the larger policy and ethical issues are dominated by Northern voices. We need Southern voices to be part of these discussions.

• Best practices in data management in the South. There is India’s open-source drug-discovery program among others, and at the ministerial level there is the India-Brazil-South Africa forum.

All of these modest recommendations, which are largely based on existing activities, experiences, and initiatives that have been mentioned at this meeting, can play a critical role in fulfilling the principles and goals articulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with its lofty assertion that everyone has the right to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

28. How to Improve Data Access and Use: An Industry Perspective

John Rumble Information International Associates, United States

The focus of my talk is on how to improve data access and use from an industrial perspective. I work for a private company now, but I worked for the National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST) for many years. During that time, one of my main responsibilities was to run the Standard Reference Data Program at NIST’s scientific and technical laboratories. Many of those data programs are run in cooperation and partnership with, as well as with direct funding from, industry. A lot of my perspective arises from my experience in working with various types of industries—from the biotechnology industry hoping to capitalize on genomics, to the concrete industry hoping to be able to build and pave roads in subfreezing weather, to the aircraft industry hoping to take advantage of new composite materials instead of good old-fashioned aluminum.

There are a lot of common features in the way that industry approaches, accesses, uses, and supports data that are useful to it. It is important then to understand how industry looks upon publicly funded data. Just to give you the point of this in advance, industry strongly applauds the open access to publicly funded data because industry is in the best position to take advantage of data from an exploitation point of view, not for scientific credit, but for revenue credit. The more data they have access to, the more comfortable a company is that it is doing things in the best possible way.

It is always useful to look at the life cycle of data. When we talk about access to data, we are really talking about one part of a multistep, continuous process. It starts with measurements and works its way around to having data resources being available and then having people use them. Then, from the use of these data resources, new needs are developed that in turn generate new measurements. This is how the data life cycle process continues.

I want us to think about this particular life cycle from the industrial perspective to see where the interactions of industry take place within this life cycle and to understand some of the places where industry can both help and take advantage of the accessibility of data. Many people do not really realize that industry plays a major role today in a lot of large scale data collection efforts, whether it be the large-scale manufacturer of small instruments that are used over and over again, such as mass spectrometers, genome sequencers, and crystallographic structure machines or all the way up to the big new colliders that have been built with a lot of cooperation from industry. Industry does play a large role in generating data, even publicly funded data, through this support of the scientific effort and through instrumentation. They are looking to make money, but I think it is important to realize that a lot of the sources of publicly funded data resources that have been built in recent years have come as a direct result of industry involvement in this part of the data cycle.

There are situations where industry gets very interested in the development of and access to data resources. Sometimes it comes in terms of direct financial support. Good examples are some of the genomic and proteomic databases that are being built where industrial firms are directly doing measurements and contributing them to larger scale data resources. Strategic moral support in the protein data bank is a good example of where industry does not necessarily provide direct support, but they have strongly encouraged the U.S. government to continue long-term support of that resource.

The knowledge support services that some of the best data scientists have developed in terms of designing data architecture, data resources, and web services came from IBM, Microsoft, and now Google. In other situations, where there are not particularly large sets of tools or methodologies to exploit data, industry does a lot of development in terms of data mining, visualization, and what I call “value added”. This is

where industry will take some publicly available data, add value to it, and then sell it. An example is the NIST mass spectral database, which contains several hundred thousand mass spectra. NIST distributes this database with a nice interface, but some of the machine manufacturers have taken that product and added an analytical package on top of it, thus enhancing the value of that publicly funded data resource by making it a more important scientific and technological tool.

Finally, one other way that industry very importantly involves itself in the data life cycle is by articulating new needs. Those of you from university research programs are well aware that industry has started many academic-industry joint programs. These programs have been started because industry realizes it has need for new scientific knowledge and measurements that it cannot satisfy itself.

Another important main point has to do with how industry accesses data and when it accesses them, why it accesses them, and the economic implications of its access. Almost any product and service that is available commercially starts as a concept. It might simply be one entrepreneur sitting at a restaurant sketching something, or the result of a long process by a complex design team. What is important to understand is when industry makes money. Industry does not make money from concepts or rough designs; it makes money from selling things.

The main point I want to make here is that the industry’s willingness to pay for data is directly related to how close in time the use of data are to the sale of a product or service. Data used years before a product is released and sold is not “valued” as highly as are data whose use has immediate impact. An example of the latter is analytical chemistry data that are used to identify an unknown substance that has affected a manufacturing process. Because the impact is immediate, companies are willing to pay many thousands of dollars for data. In contrast, companies are less willing to pay for material property data used early in a multi-year design database.

The picture I am trying to paint here is that industry needs to have access to all kinds of different data to support product development and services so they can make money. Data comes in lots of different flavors and has lots of different uses. Data also has differing impacts on the ability of industry to make money from data use depending on when that use occurs. Industry is willing to pay for data when it perceives the value of those data in helping them make more money.

What really incentivizes industry to participate more willingly in scientific data activities? How do we improve access to data? There are situations where industry’s participation in scientific data activities is extremely important to the progress of those scientific data activities. Obviously the first example that comes to mind is genomics, but genetically modified foods are another case. Other examples are pharmaceutical development, and aircraft manufacturing.

The primary motivation is the potential for increased revenue. Rarely do companies act out of goodwill. If we want industry participation in more public scientific data activities, it is perfectly acceptable to allow them to demand a business case and for you to provide that business case to them, because that is how industry makes decisions. There are subsidiary reasons, such as intellectual property rights, which eventually translate into increased revenue or increased market share. A company will support a data project if it leads to development of a new product, for example, a specific new pharmaceutical, such as a new drug for diabetes, which in turn will lead to increased revenue.

There are other less tangible ways that are also useful to think about. One is that there are many smart people in industry, and they know that new science is going to create new industry and new products. They are not sure how, and if they participate in the fundamental research that develops these scientific disciplines, they will have an opportunity to perhaps get the insights that will lead to revenue. The professional societies in the United States have incentivized industry to cooperate together. A lot of the

large-scale data programs are funded by industry through professional society programs.

I would like to end by saying that contrary to what most people think, industry really supports open access to publicly funded data. From their perspective, they are often in the best position to exploit them for whatever reasons they want to. If industry have data that it generated, there are many mechanisms to keep that proprietary data to themselves. As I already indicated, however, there are instances when they do generate data or do help the generation of data, which contributes considerably to publicly funded data resources.

Hilary I. Inyang African Continental University System Initiative8 University of North Carolina, Charlotte, United States

INTRODUCTION

To begin, I would like to describe the role of universities during three eras in Africa. The first was the pre-independence era in Africa when universities were engaged very deeply in independence movements, protests, and so forth. In Mozambique, for example, university-based intellectuals were at the forefront of protests to gain independence from the Portuguese government. At that time, African universities were at the vanguard of diverse indigenous groups that rationalized the need for the independence of African countries on the basis of the human rights to freedom and self-governance. They were not really deep contributors of data or other forms of information to economic development initiatives and governance of their countries. That role was played by colonial governments directed from Europe. This circumstance was prevalent in Africa until the late 1950s.

The 1960s, when the wind of change blew across Africa bringing with it independence, was another significant period with respect to the availability of data in Africa for national economic development programs of newly independent nations. The first set of post-independence leaders in Africa were statesmen, exemplified by Dr. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Dr. Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, Dr. Siaka Stevens of Sierra Leone, Dr. Leopold Sedhar Senghor of Senegal, Dr. Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, and Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria. Most of them were western-educated and valued good education, as well as the need to develop and use data for their governments’ economic planning and governance. The high educational standards of the era are highlighted by the fact that despite the existence of very few research institutes within the continent at that time, colleges were able to engage in intellectual enquiry to generate data and build human capacity on analytical aspects of economic program planning and implementation. However, during that era, universities were strong in the liberal arts, but not so much in the sciences, because they had not yet developed the infrastructure that would have made them competitive with those in global science.

Unfortunately, following their initial interest in democracy and the utility of knowledge systems, including data in the sustainable development of their countries, most of the early leaders overstayed their welcome in leadership positions and sometimes, turned to autocracy. The ultimate result was a wave of military coup d’états across Africa in the 1970s and 1980s, that derailed most of the long-term educational and research initiatives that would have institutionalized the generation of data for economic planning and project implementation in Africa. Most of the new military leaders installed autocracies that devalued knowledge systems and operated through edicts without regard to scientific facts and data that were not in support of their decisions. Intellectuals were often prosecuted and many were driven into exile.

Since the 1990s, there has been a continuing diminution of autocracy in Africa. The need for national planning is recognized. Most African countries have 5-year national development programs, and they are beginning to realize that this is the time to extract the intellect of their people and invest such intellect in development efforts. This era has also witnessed the emergence of continental knowledge systems consortia, professional organizations and academic institutions that target the generation of knowledge and information. Examples are: the four-campus African University of Science and Technology, the Pan African University System, and continental professional societies in virtually every major scientific field.

_____________________

8 Former president of the African Continental University System Initiative.

Organizations such as International Council for Science – Regional Office for Africa (ICSU-ROA) and UNESCO have embarked on science support activities that will also generate data. An example is the ICSU-ROA Science Plans in many thematic areas that are critical to Africa’s sustainable development. Requirements for improvements of data generation, management, and utilization systems in Africa should be viewed within the context described above.

THE ROLE OF KNOWLEDGE GENERATION INSTITUTIONS IN DATA PRODUCTION AND MANAGEMENT

What are the typical roles of universities and other institutions that are engaged in research? I see such roles to be the following:

• Supplier of options for sustainable development;

• Producer of data for decision support systems;

• Developer of human resources and capacity;

• Creator of innovative ideas and products; and

• Guardian of rationality and human rights.

The last one often puts universities in conflict with political authorities. Every dictator that shows up wants to imprison journalists and professors. Let me start by addressing some problems. There are some very large projects in Africa. Development banks such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank sponsor most of these projects. Very large companies, more recently large Chinese companies, also sponsor such big projects. A main problem with these initiatives (e.g., building a dam or developing a big mining facility) is that there are no clear requirements regarding post-project use of the data and information that they generate for other sustainable development programs of the host countries. Then, of course, there is the issue of sensitive information and how to deal with it.

Also, there is the need for coordination and collaboration. For example, most of the African countries have declared a set of activities to achieve the Millennium Development Goals, which are very specific. All of these activities will require data and other types of information for planning and implementation of projects. This is why I see that there is a need for a systematic relationship between data access programs and these efforts.

CAPACITY LIMITATIONS OF AFRICAN COUNTRIES

Furthermore, there is the issue of the resource and human capacity gaps among African countries. It is not that information is sparse in all parts of Africa on every issue. In some countries like South Africa, Tunisia and Algeria, there is a lot of information, but some countries in West Africa and Central Africa do not have adequate facilities and capabilities for research information generation on critical issues in many economic sectors. About 30 percent of the annual budget of some of these poor countries comes as foreign aid. They have other things that they consider more immediate and more expedient than developing research facilities and data management systems.

Additionally, we should always remember that Africa has a number of official languages. So, it is very difficult to do things on a region-wide basis. Even in West Africa, there are 5 Anglophone and 9 Francophone countries. In Central Africa, French and Portuguese are used, and in Equatorial Guinea, Spanish is used. Translation of documents and real-time oral speeches can be very expensive.

The level of investment in data generation activities is very limited in African countries. In fact, the entire African investment in this area is less than that of Israel. Currently, there are about 500 science parks worldwide, but less than 2 percent of those parks are in Africa. If those parks are absent, how will data be transferred or managed as we do here in places like the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina or Silicon Valley in California? There should be a clear model for how universities can interrelate with other

organizations to promote economic activities and progress. This has to be promoted through, for example, the activities of organizations like the World Bank, the African Development Bank, UNESCO, ICSU, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the African Union, the Regional Economic Blocs, and international aid organizations, as well as the African governments themselves.

PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

What are the solutions? We need to establish an African Research Foundation. Most of the efforts and money that have been spent would be better spent on the development of this critical entity. Even in Europe, where there are very strong national science or research foundations, there is still the superposition of the European Science Foundation on a continental basis, on those national capabilities. I think it is very critical to do this in Africa as well, more so when the lack of effective national research agencies is pervasive in the continent, except of course, in South Africa. An endowment fund should be attached to such an endeavor, because if there is a research foundation, it would be ineffective, if it does not have the funds to deal with issues.

As in most countries, universities in Africa emphasize three broad research disciplines: the social sciences and humanities; engineering, technology and computing sciences; and physical, biological, ecological, and other natural sciences. In parallel, governments employ a variety of policy tools: market incentives, risk communication, technology deployment, public education, and so forth. Unless there is an interplay between these academic approaches and government policies and initiatives, it is very difficult to maximize the value of data, information, science, and public policy.

I would like to address some important developments in Africa in the information technology area. There are many optical cable systems that are being implemented now in Africa. These cable systems are improving internet access in Africa. For example, the West African Cable System is reducing the cost of Internet connectivity, including access and data transfer, and mobile systems. As a complement to this development, there are about 10 satellite systems now covering various regions, including sub-Saharan Africa and the Arab countries in the north of Africa.

CONCLUSIONS

Let me conclude by stating that the formation and operation of an African Research Foundation would greatly enhance the generation of data and other types of information for regional sustainable development. Such a Foundation should have the following mandate:

- To support research for production of information, including data, for use in African sustainable development programs;

- To provide an opportunity for engagement of African and other experts and the development of African talent (in Africa and the diaspora) on science and technology research on critical issues that affect Africa; and

- To catalyze science and technology-based African entrepreneurship and improve the infrastructure for access to data in locations within and outside Africa.

If these recommendations are implemented, Africa will increase its contribution of knowledge, not only to the improvement of the quality of life in the continent, but to global sustainable development. It is a fact of history that the continent has a heritage of contributions to human development and on intellectual matters throughout the centuries.

30. The ICSU World Data System

Yasuhiro Murayama National Institute of Information and Communication Technology, Japan

My talk will include both international activities related to ICSU’s World Data System, as well as some examples of scientific database and data sharing activities related to developing countries, especially in Asian countries. I hope that the specific examples I will share with you can inspire you to promote more open access data for social benefits.

About 50 years ago, when the former “World Data Center” (WDC) system was established, the main objective was data preservation primarily for printed data sheets and films, before digital data become predominant with state-of-art technology of high-speed Internet, and huge data storage in computer servers. Those were valuable efforts to keep scientific data indispensible. Today, we get more and more data in digital form, and the size of the holdings is increasing rapidly. In Japan, other Asian countries, the United States, and Europe, we are expanding our data strategies, and scientists are concerned with how to handle the data influx. Also with digital data, the future interoperability for world-wide data centers connecting to each other can be envisioned, which was not available for data stored on paper and film.

In this context, the International Council for Science (ICSU) established the World Data System (WDS) in 2008. ICSU envisioned a global data system that would:

• Emphasize the critical importance of data in global science activities;

• Further ICSU strategic scientific outcomes by addressing pressing societal needs (e.g., sustainable development and the digital divide);

• Highlight the positive impact of universal and equitable access to data and information;

• Support services for long-term stewardship of data and information; and

• Promote and support data publication and citation.

I should mention that CODATA has also participated in such international data sharing efforts, and we are hoping for more future collaboration with CODATA. Other collaborators come from the disaster research area. We also have collaborations with international scientific unions, a number of United Nations agencies, and additional Asian and Japanese unions.

To fulfill this vision and to facilitate collaboration, I am now in process of establishing a new International Programme Office (IPO) for ICSU-WDS this year, as its acting director. The IPO is to be hosted by the National Institute of Information and Communication Technology (NICT) in Japan (NB: the internationally selected Executive Director was appointed in March 2012, and the official opening ceremony was held in Tokyo, in May 2012).

Next, I would like to address several scientific data activities carried out by myself and my institute. We have a monitoring network for solar and space science, and space weather observational data. These kind of data are important in social activities too; for example, the ionosphere is the biggest delay factor in radio navigation signals for the Global Positioning System (GPS). This is very crucial in positioning aircraft and in future precise applications.

If we want to introduce GPS-guided aircraft navigation, the networks should extend into the south Asian countries and be based upon sound science where data are shared together with those countries. Many cities also provide this kind of distributed system and use high-speed internet to link with several Japanese universities.

Future directions include scientific data cloud services, or creating a digital Earth capability that combines observational data and simulation data with informatics technologies. Better management of the data can be enabled through high-speed research network experiments, such as the Asian-Pacific Advanced Network (APAN). This kind of infrastructure enables Japanese researchers to access data from various countries in eastern and southern Asia and vice versa.

A final example focuses on university groups in Japan. They are now designing a metadata system for space and atmospheric, and interdisciplinary sciences. An improved metadata system enables more information exchanges to promote data usage and more scientific research. Universities also have various data observing networks. Some are radars in Arctic regions, while others are radars or magnetometers in Asian countries or in Antarctic stations. The starting point is a good metadata system for data in the archives.

I would like to conclude by noting that in September 2011 we will have the first World Data System conference in Kyoto, together with the WDS scientific committee meeting.

31. Libraries and Improving Data Access and Use in Developing Regions

Stephen Griffin National Science Foundation, United States

I am going to explore some of the potential roles for libraries in improving access, use and sharing of large stores of data in support of e-Science and other data-intensive scholarly inquiry. The focus will be on their application in developing countries.

Contemporary research and scholarship is increasingly characterized by the use of large-scale datasets and computationally intensive tasks. Vast amounts of data are used by scientists to better map the cosmos, build more accurate earth system models, examine in finer details the structures of living organisms, and gain insights into the behaviors of societies and individuals in a complex world increasingly dependent upon information technology.

Significantly, more humanists are rapidly integrating newly digitized corpora, digital surrogates of cultural heritage artifacts, and historical, spatial, and temporal indexed data into their scholarly endeavors. The datasets are huge by any measure. Petabyte-scale datasets are not uncommon. More raw data are being produced today than can be physically stored, and this disparity will almost certainly increase very rapidly.

Much has been accomplished by the libraries and information sciences communities over the past decade to establish basic principles, standards, object representations, descriptive metadata, and reference models needed to achieve interoperability, scalability, access, and long-term preservation and archiving of digital content.

Already, libraries have undergone significant transformation by converting collections and holdings to digital forms in prescribed formats with appropriate descriptive metadata. In addition, they have dealt with a deluge of new “born digital” data from a variety of sources. Libraries now play a central role in providing enhanced access to very large digital collections across many topic domains for a wide variety of users, but the prospect of libraries taking responsibility for large-scale raw datasets and a multitude of derivative forms of data associated with e-Science and data-intensive scholarship was not seriously considered until more recently. As a result, there is lively debate and controversy over how libraries, and particularly research libraries, should participate in providing tools and infrastructure in support of data-intensive research.

The challenges are daunting. In addition to tasks inherent in the life cycle of data and information, there are other tasks requiring new technologies and new expertise and a broader spectrum of user services. This points to the question of how graduate schools of library and information science should prepare students for the realities that await them in a digital world of knowledge resources.

For developing countries, all of that applies, but there are additional barriers that are not present in more-developed regions of the world. At the same time, perhaps there are unique opportunities that we can discover, as in some respect they are beginning at a different starting point in a long evolutionary process and may not be burdened by entrenched practices.

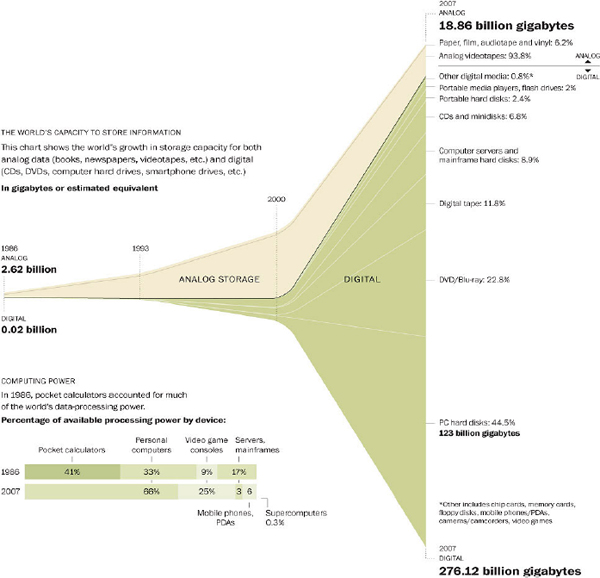

There are several points in Figure 31-1 that depicts the rapid transition from storing information on analog media to digital media. It is impressive how quickly it happened, and perhaps a bit disconcerting, too. Also, it should be noted that scientific data only represents a very small proportion of the data being produced, and all data of value require careful management to ensure reusability. Of equal importance is that the various media on which the data are stored deteriorates over time and will likely become

unreadable within a few decades. This implies that policies for physical migration be established and followed.

FIGURE 31-1 The World’s Capacity to Store Information

Credit: Hilbert, M. & López, P. (February 11, 2011). The World’s Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information. Science Magazine, 332(6025), 60-65.

Contemporary data-centered research and scholarship can be categorized based on the types of data associated with the research activity:

e-Science: A natural evolution of computational science that involves massive simulations of phenomena of scientific interest too large or small, too fast or slow, or too complex to explore in a research laboratory. e-Science is computationally-intensive and frequently involves the use of distributed network environments and grid computing.

Data-Driven Science: A rapidly growing set of applications in which analysis of large amounts of experimental data drives the overall research. The sources of data are often high-throughput digital instruments and recording devices; for example, sophisticated astronomical instruments, particle accelerators, environmental sensors, medical diagnostic equipment, and many others. The petabytes of data that may result frequently require significant computation to yield the basic data for analysis. Data-driven science is a more recent paradigm primarily dependent upon new forms of data analytics.

Data-Intensive Research and Scholarship: This includes efforts based in part on the exploration, manipulation, and analysis of diverse datasets including born-digital data, data resulting from the continuing digitization of large analog collections, digital representations of physical artifacts and complex higher-order derived data constructs. Collaboration within and across disciplines may take a key role. Interoperable and highly contextualized datasets are often essential to success.

Data-intensive research is being broadly pursued in many disciplinary domains. Scholars in the humanities and social sciences are finding new problems of compelling interest that both have a strong technology component and are based on analysis of large and heterogeneous datasets. Collaborative efforts that involve technologists and domain researchers are leading to advances in knowledge and new understanding in many areas.

In all of the categories of research described above, data visualization of research findings is common and frequently the most effective way to present results.

Early programs at NSF were instrumental in leading the way to some of the data-intensive research that we are seeing today. The Supercomputer Centers Program, which was begun in the mid-1980s, and the NSFNet program that was originally part of the Supercomputer Centers Program in the 1980s, were very important. The NSFNet was originally envisioned to be a service-type of facility for the supercomputer centers. The idea was that if one built a network connecting large computing facilities around the United States, one could share datasets and aggregate computational cycles. The notion of a network as a means for federated search of data repositories had not yet been seriously discussed.