5

Pay for Performance: Perspectives and Research

The committee's charge from the Office of Personnel Management included an examination of research on the effects of performance appraisal and merit pay plans on organizations and their employees. We have extended the scope of our review to include research on the performance effects of pay for performance plans more generally (merit, individual, and group incentive pay plans) and other research on pay system fairness and costs. We did this for two reasons. First, we found virtually no research on merit pay that directly examined its effects. Second, the research on pay for performance plans makes it clear that their effects on individual and organization performance can not be easily disentangled from other aspects of pay systems, other pay system objectives, and the broader context of an organization's strategies, structures, management and personnel systems, and environment (Galbraith, 1977; Balkin and Gomez-Mejia, 1987a; Ehrenberg and Milkovich, 1987; Milkovich and Newman, 1990).

This chapter is organized around these points. The first section describes merit, individual, and group incentive pay for performance plans and classifies them in a matrix formed by two major dimensions of plan design. We next use this matrix to review research on the influence of different pay for performance plans on the pay system objectives that organizations typically report—improving the attraction/retention/performance of successful employees, fair treatment and equity, and cost regulation, with the trade-offs among other pay objectives it entails. When relevant, we describe the contextual conditions that appear to influence plan effects or are associated with unintended, negative consequences when pay for performance plans are used. We then summarize

our conclusions drawn from this research and discuss their implications for federal policy makers.

PAY FOR PERFORMANCE PLANS: A FIELD GUIDE

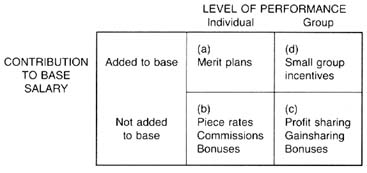

Although there is a startling array of pay for performance plan designs in use, they can be described and classified on some common design dimensions. In Figure 5-1 we have classified pay for performance plans in a two-dimensional matrix. The first dimension represents design variation in the level of performance measurement—individual or group—to which plan payouts are tied. The group level of measurement encompasses work group performance, facility (plant or department) performance, and organization performance. The second dimension represents design variation in the plan's contribution to growth in base pay: some plans add payouts to base salary; others do not.

The matrix cells in Figure 5-1 provide examples of pay for performance plans distinguished on both design dimensions. Merit plans are an example of pay for performance plans found in the first cell. They are tied to individual levels of performance measurement (typically performance appraisal ratings), and the payouts allocated under merit plans are commonly added into an individual employee's base salary. The performance appraisal ratings used with merit plans often combine both behavioral (for example, provided timely feedback to employees) and outcome (for example, reduced overhead 10 percent) measures of performance. Performance appraisal ratings are used along with the employee's pay grade, position in grade, and the company's increase budget to determine the payout each employee will receive. The average payout offered by a merit plan is typically smaller than that offered by other types of plans and is provided annually (HayGroup, Inc., 1989). (Merit pay increases do, however, compound from one year to the next—over time, outstanding performers will reach a significantly higher pay level than average performers.) Merit plans are used across the spectrum of employee groups, from hourly and clerical to high-level managers.

Examples of individual pay for performance plans in which payouts are not

FIGURE 5-1 Pay for performance plan classes.

added to base salaries—cell b—include piece rate and sales commission plans. Piece rate plans involve engineered standards of hourly or daily production. Workers receive a base wage for production that meets standard and incentive payments for production above standard. Piece rate plans are most commonly found in hourly, clerical, and technical jobs. Sales commission plans tie pay increases to specific individual contributions, such as satisfactory completion of a major project or meeting a quantitative sales or revenue target. These plans are most commonly found among sales employees. Payouts under individual incentive plans are typically larger than those found under merit plans (HayGroup, Inc., 1989) and are often made more frequently (piece rate plans, for example, can pay out every week).

It is important to note that, although individual incentive plans can offer relatively large payouts that increase as an employee's performance increases, they also carry the risk of no payouts if performance thresholds are not reached. Thus, unless employers make market or cost-of-living adjustments to base salaries, individual incentives pose the risk of lower earnings for employees and the potential advantage of lower proportional labor costs for employers. The same is true of group incentive plans.

The matrix in Figure 5-1 helps to simplify and guide our discussion of research on pay for performance plans, but it is difficult to classify all plans neatly into one cell or another. Bonus plans—particularly those typical for managerial and professional employees—are a good example. These plans often combine both individual- and group-level measures of performance, with an emphasis on the latter. For example, a managerial bonus plan may combine measures of departmental productivity and cost control with individual behavioral measures, such as ''develops employees." Like the other individual and group incentive plans, these bonus plans offer relatively large payments that are not added into base salaries (HayGroup, Inc., 1989), but they do not necessarily pay out more than once a year. We consider these types of bonus plans under research on group incentives.

Pay for performance plans tied to group levels of measurement can, in principle, also be divided into those that add payouts to base salaries and those that do not. However, few examples of group plans that add payouts into base salaries exist (cell d in Figure 5-1). More common are plans that tie payouts to work group, facility (such as a plant or department), or organization performance measures and do not add pay into base salaries (cell c). There are many variations on profit-sharing plans, but most link payouts to selected organization profit measures and often pay out quarterly. A cash profit-sharing plan, for example, might specify that each employee covered will receive a payout equal to 15 percent of salary if the company's profit targets are met. Gainsharing plans, like profit-sharing, come in many forms, but all tie payouts to some measure of work group or facility performance, and most pay out more than once a year. Traditional gainsharing plans, such as Scanlon, Rucker, or

Improshare plans (named by or for their inventors), commonly provide a monthly bonus to workers of a production line or plant. The bonus is based on value added or cost savings, defined as the difference between current production or labor costs and the historical averages of these costs (as established by accounting data). Savings are split between employees and management; the employees' share of the savings is then typically allocated to each employee as some uniform percentage of base pay.

Our choice of matrix dimensions was deliberate; they distinguish the major differences between merit pay and other types of pay for performance plans, and they reflect distinctions made in the research we reviewed. We refer to the matrix throughout our review of research to help distinguish the four types of pay for performance plans and the research findings related to each.

PAY FOR PERFORMANCE: RESEARCH FINDINGS

Organization pay objectives include motivating employees to perform, as well as attracting and retaining them; the fair and equitable treatment of employees; and regulating labor costs. We are interested in research on how pay for performance plans influence an organization's ability to meet these objectives and in the conclusions we can draw—particularly regarding merit pay plans. Obviously, the pay objectives listed are related, and organizations will face trade-offs in trying to meet them, whether a particular pay for performance plan or no pay for performance plan is adopted. We deal with these trade-offs in a subsequent section.

Do pay for performance plans help sustain or improve individual and group or organization performance? Research examines this question most directly, and we review it first.

Motivating Employee Performance

The research most directly related to questions about the impact of pay for performance plans on individual and organization performance comes from theory and empirical study of work motivation. The social sciences have produced many theories to explain how making pay increases contingent on performance might motivate employees to expend more effort and to direct that effort toward achieving organizational performance goals. Expectancy theory (Vroom, 1964) has been the most extensively tested, and there appears to be a general consensus that it provides a convincing (if simplistic) psychological rationale for why pay for performance plans can enhance employee efforts, and an understanding of the general conditions under which the plans work best (Lawler, 1971; Campbell and Pritchard, 1976; Dyer and Schwab, 1982; Pinder, 1984; Kanfer, 1990). Expectancy theory predicts that employee motivation

will be enhanced, and the likelihood of desired performance increased, under pay for performance plans when the following conditions are met:

-

Employees understand the plan performance goals and view them as "doable" given their own abilities, skills, and the restrictions posed by task structure and other aspects of organization context;

-

There is a clear link between performance and pay increases that is consistently communicated and followed through; and

-

Employees value pay increases and view the pay increases associated with a plan as meaningful (that is, large enough to justify the effort required to achieve plan performance goals).

Goal-setting theory (Locke, 1968; Locke et al., 1970), also well tested, complements expectancy theory predictions about the links between pay and performance by further describing the conditions under which employees see plan performance goals as doable. According to Locke et al. (1981) the goal-setting process is most likely to improve employee performance when goals are specific, moderately challenging, and accepted by employees. In addition, feedback, supervisory support, and a pay for performance plan making pay increases—particularly "meaningful" increases—contingent on goal attainment appear to increase the likelihood that employees will achieve performance goals.

Taken together, expectancy and goal-setting theories predict that pay for performance plans can improve performance by directing employee efforts toward organizationally defined goals, and by increasing the likelihood that those goals will be achieved—given that conditions such as doable goals, specific goals, acceptable goals, meaningful increases, consistent communication and feedback are met.

Individual Incentive Plans

Among the pay for performance plans displayed in our matrix (Figure 5-1, cell b), individual incentive plans, such as piece rates, bonuses, and commissions, most closely approximate expectancy and goal-setting theory conditions. Individual incentive plans tie pay increases to individual level, quantitative performance measures. It is generally believed that employees view individual-level measures as more doable, because they are more likely to be under the individual's direct control. This is in contrast to group incentive plans (cells c and d in Figure 5-1), which are typically tied to measures of work group, facility, or organization performance. Similarly, quantitative measures are seen as more acceptable to employees because their achievement is less likely to be distorted and more directive because they dictate specific goals. This is in contrast to merit plans (cell a in Figure 5-1), which are typically tied to more qualitative, less specific measures of performance (see Lawler, 1971, 1973, for a more detailed analysis of these points). Individual incentive plans

also typically offer larger, and thus potentially more meaningful, payouts than most merit pay plans.

Given that individual incentive plans meet several of the ideal motivational conditions prescribed by expectancy and goal-setting theories, it is not surprising that related empirical studies tend to focus on individual rather than merit or group incentive plans. In reviews of expectancy theory research, Campbell and Pritchard (1976), Dyer and Schwab (1982), and Ilgen (1990) all agree that these studies establish the positive effect of individual incentive plans on employee performance. The studies reviewed include both correlational field studies and experimental laboratory studies, with the correlational studies predominating. While these studies were primarily designed to test specific components of expectancy theory models, they all show simple correlations, ranging from .30 and .40, between expectancy theory conditions and individual performance measures; this means that, when these conditions are met, 9 to 16 percent of the variance in individual performance can be explained by differences in incentives.

Cumulative studies (primarily laboratory) also support goal-setting theory predictions that specific goals, goal acceptance, and so forth, will increase employee goal achievement—in some cases, by as much as 30 percent over baseline measures (Locke et al., 1981). A laboratory study by Pritchard and Curts (1973) also reported that individual pay incentives increased the probability of goal achievement, but only if the incentive amount was meaningful. In this study "meaningful" was three dollars versus fifty cents versus no payment for different levels of goal achievement on a simple sorting task. Only the three-dollar incentive had a significant effect on individual goal achievement. Similar findings have been reported by others (see Terborg and Miller, 1978).

There are also some early field studies of piece-rate-type individual incentive plans conducted in the wake of claims made by Frederick W. Taylor (1911), the prophet of "scientific management" and inventor of the time and motion study. The more methodologically sound studies generally compared the productivity of manufacturing workers paid by the hour and those paid on a piece rate plan, reporting that workers paid on piece rates were substantially more productive—between 12 and 30 percent more productive—as long as 12 weeks after piece rates were introduced (Burnett, 1925; Wyatt, 1934; Roethlisberger and Dickson, 1939).

Viewed as a whole, these studies establish that individual incentives can have positive effects on individual employee performance. But it is also important to understand the restricted organizational conditions under which these results are observed without accompanying unintended, negative consequences. Case studies suggest that individual incentive plans are most problem-free when the employees covered have relatively simple, structured jobs, when the performance goals are under the control of the employees, when performance goals

are quantitative and relatively unambiguous, and when frequent, relatively large payments are offered for performance achievement.

There are a number of case studies that document the potentially negative, unintended consequences of using individual incentive plans outside these restricted conditions. Lawler (1973) summarizes the results of these case studies and their implications for organizations. He points out that individual incentive plans can lead employees to (1) neglect aspects of the job that are not covered in the plan performance goals; (2) encourage gaming or the reporting of invalid data on performance, especially when employees distrust management; and (3) clash with work group norms, resulting in negative social outcomes for good performers.

Babchuk and Goode (1951) reported an example of neglecting aspects of a job not covered by plan performance goals. Their case study of retail sales employees in a department store showed that when an individual incentive plan tying pay increases to sales volume was introduced, sales volume increased, but work on stock inventory and merchandise displays suffered. Employees were uncooperative, to the point of "stealing" sales from one another and hiding desirable items to sell during individual shifts. Whyte (1955) and Argyris (1964) provided examples of how individuals on piece rate incentives or bonus plans tied to budget outcomes distorted performance data. Whyte described how workers on piece rate plans engaged in games with the time study man who was trying to engineer a production standard; Argyris described how managers covered by bonus plans tied to budgets bargained with their supervisors to get a favorable budget standard. Many studies of individual incentive plans—from the Roethlisberger and Dickson field experiments to case studies like those of Whyte—have shown clashes between work group production norms and high production by individual workers, which led to negative social sanctions for the high performers (for example, social ostracism by the group).

These studies also suggested that development of restrictive social norms had some economic foundation: employees feared that high levels of production would lead to negative economic consequences such as job loss, lower incentive rates, or higher production standards. Restrictive norms were also more common when employee-management relations were poor, and employees generally distrusted managers.

These findings suggest the dangers of using individual incentive plans for employees in complex, interdependent jobs requiring work group cooperation; in instances in which employees generally distrust management; or in an economic environment that makes job loss or the manipulation of incentive performance standards likely. Indeed, a recent study by Brown (1990) reported that manufacturing organizations were less likely to use piece rate incentives for hourly workers when their jobs were more complex (a variety of duties) or when their assigned tasks emphasized quality over quantity. Since many modern

organizations face one or both of these conditions—especially complex, interdependent jobs—but may still be unwilling to bypass the potential performance improvements promised by individual incentives, some researchers suggest that they have adopted merit plans and group incentive plans in an effort to reap those benefits without the negative consequences (Lawler, 1973; Mitchell and Broderick, 1991).

Merit Pay Plans

It is not difficult to view merit pay plan design as a means of overcoming some of the unintended consequences of individual incentive plans. This is especially true when merit plans are considered in the context of more complex managerial and professional jobs. As we document in the next chapter, merit pay plans are almost universally used for managerial and professional employees in large private-sector organizations. The most common merit plan design is a "merit grid" that directs supervisors to allocate annual pay increases according to an employee's salary grade, position in the grade, and individual performance appraisal rating. The type of performance appraisal most commonly used for managerial and professional jobs involves a management-by-objective (MBO) format in which a supervisor and an employee jointly define annual job objectives—typically both qualitative and quantitative ones. The rating categories or standards generated from MBO appraisals are usually qualitative and broadly defined. Most organizations use three to five categories that differentiate among top performers, acceptable performers (one to two categories), and poor or unsatisfactory performers (one to two categories), with the acceptable category (or categories) covering the majority of employees (Wyatt Company, 1987; Bretz and Milkovich, 1989; HayGroup, Inc., 1989). Merit plan payouts are relatively small (in the private sector the average payout for the last five years has hovered around 5 percent of base salary, compared with middle management/professional bonus payouts of 18 percent plus—HayGroup, Inc., 1989); however, they are added into an employee's base salary while bonuses typically are not. This addition of payouts to base offers the potential for cumulative long-term salary growth not typical of other salary plans.

The use of an objectives-based performance appraisal format might be reasonably viewed as recognition that it is difficult to capture all the important aspects of managerial and professional jobs in a single, comprehensive measure such as "sales volume"; multiple measures, quantitative and qualitative, might be developed in such appraisal formats, thus decreasing the probability that important aspects of a job will be ignored. The choice of a performance appraisal format may also assume that the perspectives of both supervisor and employee are needed to set appropriate objectives and avoid gaming. The broader performance appraisal rating categories typical of merit pay plans may also tend to decrease clashes between work group norms and an individual performer,

since the majority of employees are rated as acceptable. The relatively smaller payouts and their addition to base salaries could also make merit plans seem less economically threatening than individual incentive plans.

Merit plan design characteristics, intended to diminish the potentially negative consequences of individual incentive plans, can, however, also dilute their motivation and performance effects. Performance appraisal objectives are typically less specific than the quantitative ones found under individual incentive plans. Employees may thus see them as less doable and more subject to multiple interpretations, and their attainment may be less clearly linked to employee performance. Pay increases are smaller and may be viewed as less meaningful; the addition of pay increases into base salaries may also dilute the pay for performance link (Lawler, 1981; Krzystofiak et al., 1982). Many management theorists have suggested that employers focus on the process aspects of performance appraisal and merit plans in order to enhance their motivational potential (see Hackman et al., 1977; Latham and Wexley, 1981; and Murphy and Cleveland, 1991, for reviews). For example, employee-supervisor interaction and bargaining during performance appraisal objective-setting could increase an employee's commitment and understanding of goals and feelings of trust toward management. Training both supervisors and employees in how to use performance appraisal objective-setting, feedback, and negotiation effectively is recommended. Communication of merit pay plans as a means of differentiating individual base salaries according to long-term career performance is also suggested as a means of helping employees to see these plans as providing meaningful pay increase potential. Our review of merit pay practices in the next chapter shows that some organizations are following these recommendations.

There is very little research on merit pay plans in general nor on the relationship between merit pay plans and performance—either individual or group—in particular.

In a recent review of research on merit plans, Heneman (1990) reported that studies examining the relationship between merit pay and measures of individual motivation, job satisfaction, pay satisfaction, and performance ratings have produced mixed results. The field studies comparing managers and professionals under merit plans with those under seniority-related pay increase plans, or no formal increase plan, suggest that the presence of a merit plan positively influences measures of employee job satisfaction and employee perceptions of the link between pay and performance. In several of these studies, the stronger measures of job satisfaction and of employee perceptions of pay-to-performance links found under merit pay plans were also correlated with higher individual performance ratings (Kopelman, 1976; Greene, 1978; Allan and Rosenberg, 1986; Hills et al., 1988). However, other field studies, notably those of Pearce and Perry (1983) and Pearce et al. (1985), reported that over the three years following merit plan implementation among Social Security office

managers, perceptions of pay and performance links declined, and department level measures of performance did not change.

Heneman's review and the reports of the other researchers cited all point out the many methodological limitations on the few existing studies: their correlational nature, the lack of good baseline measures, reliance on opinions for performance measurement, and the lack of control over organizational factors that might be expected to work against positive merit pay plan effects. Although many of these limitations probably reflect organizational reality, it is impossible to draw conclusions about the relationships between merit pay plans and performance from this research. The research also offers no means for comparing the short- or long-term performance effects of merit plans with those of other incentive plans.

Group Incentive Plans

The adoption of group incentive plans may provide a way to accommodate the complexity and interdependence of jobs, the need for work group cooperation, and the existence of work group performance norms and still offer the motivational potential of clear goals, clear pay-to-performance links, and relatively large pay increases. Most of the group incentives used today—gainsharing and profit-sharing plans—resemble individual incentive plans; they are tied to relatively quantitative measures of performance, offer relatively large payouts, and do not add payouts into base salaries. Unlike individual incentive plans, however, group incentives are tied to more aggregate measures of performance—at the level of the work group, facility/plant/office, or organization, so that the link between individual employee performance and payoff is sharply attenuated.

While group incentive plans might reasonably be predicted to offer some motivational potential for performance improvements, such a prediction requires a sizable inferential leap from the expectancy and goal-setting literature. Two of the three conditions of expectancy theory—that goals be doable and that the link between employee performance and pay be clear—are not well satisfied. The major motivational drawback to group incentives appears to be the difficulty an individual employee may have in seeing how his or her effort gets translated into the group performance measures on which payouts are based. Academics and other professionals experienced in the design and implementation of group incentive plans emphasize the importance of organization conditions that foster employees' beliefs about their ability to influence aggregate performance measures (O'Dell, 1981; U.S. General Accounting Office, 1981; Graham-Moore and Ross, 1983; Bullock and Lawler, 1984; Hewitt Associates, 1985).

Examples of such conditions include the following: management willingness to encourage employee participation in group plan design and in day-to-day

work decisions; an emphasis on communications and sharing of information relevant to plan performance; joint employee-management willingness to change plan formulas and measures as needed; cooperation among unions, employees, and managers in designing and implementing the group plan and tailoring plans to the smallest feasible group; and an economic environment that makes plan payouts feasible. All of these suggestions seem reasonable but are largely the product of expert judgment, not empirical studies.

Renewed interest in gainsharing, profit-sharing, and other types of group incentives during the 1980s (although not necessarily accompanied by increased adoption of such plans, as we document in the next chapter) has led to several reviews of research on group incentives (Milkovich, 1986; Hammer, 1988; Mitchell et al., 1990). Two methodologically rigorous gainsharing studies examined the productivity effects of traditional gainsharing plans covering nonexempt employees in relatively complex, interdependent jobs in manufacturing plants. Schuster's (1984a) was a controlled, longitudinal study (five years) examining the effects of introducing gainsharing plans on measures of plant productivity; he reported that for half of the 28 sites, there were immediate, significant productivity gains over baseline measures and continued effects over the study period. He noted that less successful plans tended to be in sites where many different plans were adopted to cover work group teams instead of a plant-wide plan, when infrequent bonus payments were made, when union-management relations were poor, and when management attempted to adjust standards and bonus formulas without employee participation. Wagner et al. (1988) also examined five years of plant productivity data before and after the introduction of gainsharing and also reported significant increases in plant productivity.

Much of the research on gainsharing is based on single case studies lacking rigorous methodological controls. There are few reports of gainsharing "failures." In general, the case studies report multiple, beneficial effects from gainsharing: enhanced work group cooperation, more innovation, and more effort; improved management-labor relations; higher acceptance of new technologies; worker demands for better, more efficient management; and higher overall productivity. Mitchell et al. (1990:69-71) note that an analysis of this case study literature leaves the impression that job design enabling team work, smaller organizational size and more flexible technology, employee participation, and favorable managerial attitudes about gainsharing plans may all be critical to their success in improving productivity, but that the research does not allow conclusions beyond "gainsharing may work in different situations for different reasons." This suggests that many beneficial effects attributed to gainsharing—including productivity effects—may be as much due to the contextual conditions as to the introduction of gainsharing. Indeed, there is an emerging case study literature supporting this view (see Beer et al., 1990). Some go so far as to suggest that organizational context should be the only focus of productivity improvement efforts; that pay for performance plans will ultimately

depress productivity (Deming, 1986; Scholtes, 1987). The research evidence cannot confirm or deny any of these alternatives.

Gainsharing plans have been most common in manufacturing settings, covering mostly nonmanagement employees, and the research on gainsharing is thus restricted to these private-sector settings and employees. Mitchell et al. (1990) report that research on profit-sharing plans covering nonmanagerial employees is even more scarce and less rigorous than research on gainsharing. They note that the limited case study research available suggests that profit-sharing plans are less likely than gainsharing plans to improve performance of nonmanagerial employees. Expectancy and goal-setting theories would predict this result because it is difficult to see how these employees would translate their job efforts into organizational profit improvements. Advocates of profit-sharing plans (Metzger, 1978; Profit-Sharing Council of America, 1984), however, point out other potential benefits of plan adoption, most notably the improved employee commitment to the organization and understanding of its business that can emerge when information relevant to profit generation is shared with employees as part of the plan. As we noted for gainsharing plans, it is possible that these benefits would result from organization conditions like information sharing absent a profit-sharing plan. Profit-sharing plans and managerial bonus plans have traditionally been used as part of executive and middle management compensation packages; typically they tie payments to organizational financial outcomes (such as return on assets, return on equity, and so forth). Most of the studies of executive compensation (reviewed by Ehrenberg and Milkovich, 1987), however, examine the relationship between overall compensation levels and firm performance, not between profit-sharing and firm performance.

However, a recent study by Kahn and Sherer (1990) explored the impact of managerial bonus plans on the performance of managers in the year following a bonus award. The company studied had a bonus plan for which all middle-to higher-level managers were eligible, but which in practice targeted critical higher-level managers for the most substantial performance payments. Targeted managers were eligible for bonuses representing 20 percent of base salaries; other managers were eligible for 10 percent bonuses. The bonus plan was tied to a management-by-objective appraisal system that used some common individual-level behavioral and outcome measures for all managers. Controlling for pay level, previous performance, and seniority, Kahn and Sherer found that the targeted critical managers had significantly higher performance ratings in the year following bonus payment than less critical, nontargeted managers. They suggested that higher potential payouts were highly correlated with higher performance effects.

Another recent study by Gerhart and Milkovich (1990) analyzed five years of firm performance and compensation data for 16,000 mid-level managers and professionals in 200 large corporations. They controlled for individual, job, and

organizational conditions and found that firms in which managers and professionals had higher profit-sharing bonus potential (measured as the percentage of base salary represented by the bonus) also had better performance (measured as return on assets) in the year following the bonus payment. Specifically, every 10 percent bonus increase was associated with a 1.5 percent increase in return on assets. This association, while not statistically significant, is certainly not trivial in absolute terms. Although the study did not control for prior profit history, these results suggest that profit-sharing plans may have a positive impact on organizational performance among the higher-level managerial and professional employees whose jobs are most directly related to financial outcomes. However, another study by Abowd (1990) qualifies these results, suggesting that profit-sharing bonuses for higher-level employees will be more likely to improve firm performance when economic conditions make such improvements realistic.

Summary

Most of the research examining the relationship between pay for performance plans and performance has focused on individual incentive plans such as piece rates. By design, these plans most closely approximate the ideal motivational conditions prescribed by expectancy and goal-setting theories, and the research indicates that they can motivate employees and improve individual-level performance. However, the contextual conditions under which these plans improve performance without negative, unintended consequences are restricted; these conditions include simple, structured jobs in which employees are autonomous, work settings in which employees trust management to set fair and accurate performance goals, and an economic environment in which employees feel that their jobs and basic wage levels are relatively secure. Because these conditions—especially the job conditions—are not found collectively in many organizations and do not apply to many jobs, some researchers suggest that organizations might adopt merit pay plans or group incentive plans in an effort to avoid the potentially negative consequences of individual incentive plans while still reaping some of their performance-enhancing benefits.

Merit pay plans have some design features, such as the addition of pay increases to base salary, and the use of individual performance measures, including both quantitative and qualitative objectives, that can help avoid some of the negative consequences of individual incentives plans; these characteristics may also dilute the plans' potential to motivate employees. Organizations, however, can take steps to strengthen the motivational impact of merit plans. While there is not a sufficient body of research on merit pay plans to confirm it, we think it likely that to the extent merit pay plans approximate the motivational strengths of individual incentive plans, they will, at minimum, sustain individual performance and could improve it. Our conclusion is based on inference from the research on individual incentives.

Given the restricted conditions under which individual incentive plans work best, some organizations have adopted group incentive plans. Gainsharing and profit-sharing plan designs retain many of the motivational features of individual incentive plans—quantitative performance goals, relatively large, frequent payments—but it is not as easy for individuals to see how their performance contributes to group-level measures, and the motivational pay-to-performance link is thus weakened. At the same time, group-level performance measures may be more appropriate than individual measures when work group cooperation is needed and when new technology or other work changes make it difficult to structure individual jobs, although there is little theory or research to substantiate this claim.

The research evidence (all based on private-sector experience) suggests that gainsharing and profit-sharing plans are associated with improved group- or organizational-level productivity and financial performance. This research does not, however, allow us to disentangle the effects of group plans on performance from the effects of many other contextual conditions usually associated with the design and implementation of group pay plans. Consequently, we cannot say that group plans cause performance changes or specify how they do so. Indeed, some researchers believe that it is the right combination of contextual conditions that is critical to improved performance, not the performance plans themselves.

This research provides us with at least a partial list of contextual conditions that may influence pay for performance plan effects. These include task, organizational, and environmental conditions. Task conditions reflect the nature of the organization's work, including the complexity and interdependence of jobs, the diversity of occupations and skills required, and the pace of technological change. Organizational conditions include work force size and diversity, levels of employee trust, the degree of participative management, existing performance norms, and levels of work force skill and ability (including those of management). Organizational conditions are all influenced by the organization's history, strategic goals, and personnel policies and practices. Environmental conditions include economic pressures and opportunities for growth, which influence the organization's ability to fund performance plans and the extent to which employees may feel economically threatened by the use of pay for performance plans. The presence of unions is another environmental factor that may influence pay for performance plan effects.

Employee Attraction and Retention

Organizations typically report that they want their pay systems to help them attract and retain higher-quality, better-performing employees. A conceptual case can be made for how pay for performance plans might influence the attraction and retention of these better employees. An underlying framework in

many social science disciplines describes the employee-employer relationship as an exchange in which the employer offers inducements (certain working conditions, opportunities, pay, job security, and so forth) in exchange for employee contributions that include joining and remaining in the organization (see, for example, March and Simon, 1958; Mahoney, 1979). This framework assumes that employees globally assess the inducements (including pay) an employer offers relative to their own preferences, their abilities and skills, and their other employment opportunities, and then make decisions about joining the organization accordingly. Similarly, employees already within the organization make global assessments of the continuing inducements offered relative to their own contributions. (The employer side of this exchange is primarily concerned with the relative benefits gained given the cost of inducements; this is discussed in our review of research on pay for performance and cost regulation.)

Unfortunately, the empirical research examining the relationship of pay to an employer's ability to attract and retain high-performing employees is limited, and there is virtually no research examining the impact of pay for performance on these objectives. In a 1990 review of research on the strategies that organizations use to attract employees, Rynes and Barber note support for the importance of pay in employee assessments of the inducements an employer offers, and for the ability of relatively higher pay inducements (specifically salaries, recruitment and retention bonuses, and educational incentives) to increase the quality and quantity of an organization's recruitment pool. These findings provide some support for conceptual proposals about pay and the attraction of better employees, but they do not help us pinpoint the influence of pay for performance. In a review of research on turnover and retention, we found only one experimental study relating retention to the adoption of a merit pay system involving nonclerical, white-collar workers in U.S. Navy labs (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 1988b). This study reported modest reductions in overall voluntary turnover and considerable reductions in turnover among superior performers (as rated by the performance appraisal system) in the labs using merit pay plans. One study is not sufficient to support any general propositions about the relationship of pay for performance and retention. However, if high wages generally reduce turnover, we can infer that merit pay probably has a positive influence on the retention of those employees who receive high performance ratings and, therefore, the largest pay increases from one year to the next.

In summary, the role that pay for performance plans can play in an organization's ability to attract and retain the best performers can be conceived in terms of an inducements-contributions exchange between employee and employer. This conceptual framework suggests that an employee assesses the pay for performance plan relative to other payments, working conditions, and other employment or promotional opportunities in deciding to join or remain with the organization. Certainly, if all else is equal, pay for performance plans

should help attract and retain better performers. This framework assumes the importance of context; it also emphasizes that individuals will assess pay for performance plans and other payments relative to everything else the organization offers, thus placing pay in a potentially less prominent position than does the research on performance motivation. For example, some individuals, though opposed to pay for performance plans, might still be willing to stay with an organization offering a challenging job, pleasant working conditions, and opportunities for promotion. Unfortunately, although a conceptual case can be made for the ability of pay for performance plans to help an organization attract and retain the best performers, the research does not allow us to confirm it.

Fair Treatment and Equity

The adoption of pay for performance plans that treat employees fairly and equitably seems an inherently good and ethical pursuit in and of itself. While organizations undoubtedly recognize this, they also realize that different people have different definitions of what is fair and equitable. Organizations thus frame their objectives pragmatically. They want their pay systems to be viewed as fair and equitable by multiple stakeholders: employees; managers, owners, and top managers; other interested parties at one remove, such as unions, associations, regulatory agencies; and the public (Beer et al., 1985). Employee perceptions of pay system fairness are thought to be related to their motivation to perform, and this is one reason that organizations are interested in fairness. Organizations are also interested in pay system fairness because there are laws and regulations that require it, because employees and their representatives (unions and associations) demand it, and because society (representing potential constituents, clients, or customers) is thought to smile on organizations with a reputation for treating their employees fairly.

The research on fair treatment and equity in organizations has been mostly concerned with employee perceptions (as opposed to the perceptions of unions, associations, or other interested organization stakeholders). Theories of organizational justice distinguish between distributive and procedural concerns (Cohen and Greenberg, 1982; Greenberg, 1987; for a detailed review of theory and research on organizational justice, see Greenberg, 1990). In application to pay, theories of distributive justice suggest that employees judge the fairness of their pay outcomes by gauging how much they receive, relative to their contributions, and then making comparisons against the reward/contribution ratios of people or groups they consider similar in terms of contributions. If the employee judges that he or she is comparatively unfairly paid, negative reactions are predicted (such as higher absenteeism, lower performance, higher grievance rates, and so forth) (see Adams, 1965; Mowday, 1987). Pay distribution concerns would involve employee perceptions of the fairness of pay outcomes such as the level

of pay offered, the pay offered for different types of jobs, and the amount of pay increase received.

Distributive justice theories also predict that some employees, particularly those managing or administering pay systems, will be concerned with distributing pay increases according to rules that the majority will view as fair, thereby reducing conflict (Greenberg and Levanthal, 1976). These distribution concerns encompass employee perceptions of the fairness of basic pay policies, especially those about how pay increases are allocated. Examples of pay increase policies include increases tied to performance, increases based on seniority, across the board (or equality) increases, and higher increases for those with greater needs.

Procedural justice theories suggest that employees have expectations about how organization procedures will influence their ability to meet their own goals, and that these expectations will be shaped by both individual preferences and prevailing moral and ethnical standards (Walker et al., 1979; Brett, 1986). Work in procedural justice also suggests that the consistency with which procedures designed to ensure justice are followed in practice is an important determinant of their perceived fairness (Levanthal et al., 1980). In application to pay, procedural concerns would involve employee perceptions about the fairness of procedures used to design and administer pay. The extent to which employees have the opportunity to participate in pay design decisions, the quality and timeliness of information provided them, the degree to which the rules governing pay allocations are consistently followed, the availability of channels for appeal and due process, and the organization's safeguards against bias and inconsistency are all thought to influence employees' perceptions about fair treatment (Greenberg, 1986a).

Research examining distributive and procedural theories in a pay context is scarce; there are no studies that can directly answer questions about the perceived fairness of different types of pay for performance plans. The existing research on distributive justice does suggest that employee perceptions about the fairness of pay distributions do affect their pay satisfaction. Research on procedural justice suggests that employee perceptions about the fairness of pay design and administration procedures can also affect their pay satisfaction, as well as the degree to which they trust management and their commitment to the organization. None of this research, however, allows us to determine causality.

Early research (mostly case studies and laboratory experiments) examining employee perceptions of the fairness of pay distribution focused on differences in pay for different jobs or specific tasks (Whyte, 1955; Livernash, 1957; Jaques, 1961; Adams, 1965; Lawler, 1971). It supported theoretical predictions that employees do judge the ratio of their pay outcomes to their work contributions against selected comparison groups, and that negative reactions—primarily pay dissatisfaction—can occur if comparisons are unfavorable. It also suggested at least three major pay comparison groups—employees in similar jobs outside the organization, employees in similar jobs within the organization, and employees

in the same job within the organization—to which pay designers should be sensitive. Recent reviews of work on pay satisfaction (Heneman, 1985; Miceli and Lane, 1990) also suggest that pay satisfaction is multidimensional; that employees make judgments about their satisfaction with multiple distributive outcomes: base salaries, pay increases, and so forth. This research does not, however, allow us to determine whether dissatisfaction with one type of pay outcome (such as base salary) affects satisfaction with other pay outcomes (such as merit increases).

There have been a few correlational field studies on employee perceptions of procedural fairness—most of them examining the procedures surrounding performance appraisal ratings used to allocate pay (Landy et al., 1978, 1980; Dipboye and de Pontbriand, 1981; Greenberg, 1986b; Folger and Konovsky, 1989). These studies suggest that opportunity for employees to have input into performance evaluations is a key determinant of their perceptions about its fairness. For example, when employees are able to interact with supervisors in setting performance objectives, when they have some recourse for changing objectives due to unforeseen circumstances, and when there are channels for appealing ratings and pay increase decisions, they will be more likely to see performance appraisals and any pay allocations based on them as fair. Other studies suggest the importance of explanations about how performance appraisal works, basing appraisals on accurate information (for example, current job descriptions), and good interpersonal relationships between supervisor and employee in determining employee perceptions of fairness.

As we noted earlier, this research is all focused on employee perceptions of procedural fairness, but the findings are consistent with the body of judicial cases shaping the legal definition of fair (and nondiscriminatory) performance appraisal practices (Feild and Holley, 1982). These findings are also consistent with some of the research on pay satisfaction suggesting the importance of pay administration procedures (communication of pay policies, employee participation in job evaluation, and so forth) to higher pay satisfaction (Dyer and Theriault, 1976; Weiner, 1980; Heneman, 1985).

There is no body of research on employee perceptions of the fairness of different pay increase policies—those based on performance, seniority, or equality/across the board or according to need. Several studies (Dyer et al., 1976; Fossum and Fitch, 1985; Hills et al., 1987) suggest that private-sector managers believe that pay increases should be tied to performance; the perceptions of other employee groups are not well documented. Evidence from public-sector professional and managerial employees suggests that their beliefs differ from those of private-sector managers. Although there appears from attitude surveys of federal workers to be support of merit pay in principle, there is other evidence of a disinclination to differentiate among employees. For example, several managers' associations have proposed that performance appraisals have but two scale points, satisfactory and unsatisfactory (Professional Managers

Association, 1989). And a recent report of the Advisory Committee on Federal Pay (1990) suggests that there is a fairly strong impulse to see equity in terms of standardization or comparability of pay levels for employees in the same grade and with the same length of service.

The research on fairness and equity does not allow us to draw distinctions among the different pay for performance plans illustrated in Figure 5-1. Presumably distributive and procedural fairness will be important considerations in the adoption of any type of pay for performance plan. Mitchell et al. (1990) do, however, point out that individual and group incentive plans that offer relatively large pay increases, which are not added into base (matrix cells two and three), will over time place more of an employee's total pay at risk, regardless of whether an employee is in a very high- or very low-paying job. While such risks have been common in many higher-paying jobs (for example profit-sharing plans in top management), their fairness in lower-paying jobs has been questioned. Organizations may want to consider this in adopting individual and group incentives for lower-paid employee groups.

In summary, we believe that this research suggests several points relevant to the relationship between pay for performance plans and fair treatment or equity, although none of it allows us to draw any conclusions about specific types of pay for performance plans. The research does confirm that the perceived fairness of the distribution of pay increases will influence employees' pay satisfaction. It suggests at least three groups against which employees may assess the fairness of their pay—people in similar jobs outside the organization, people in similar jobs inside the organization, and people in the same job or work group inside the organization. This implies that employers might consider how their pay systems measure up to these three groups in designing the system, in deciding whether to use the same system throughout the organization, and in communications about pay in their efforts to improve employee perceptions about the fairness of pay distributions.

The research also suggests that employee perceptions of procedural fairness can influence their satisfaction with pay, their level of trust in management, and their overall commitment to the organization. Evidence of procedural fairness also appears to be important to other organization stakeholders such as regulatory agencies and unions and associations. This implies that organizations might usefully invest in communications, training, appeals channels, and employee participation in order to ensure procedural fairness.

Finally, the research suggests that there are different beliefs about how pay increases should be allocated—performance, seniority, across the board, and so forth—throughout U.S. society, although pay for performance beliefs appear to dominate among managerial employees in the private sector. The very existence of different beliefs, however, suggests that organizations trying to change their pay increase policies may have to deal with employees' perceptions of these policies as unfair. We base this notion on theories of procedural fairness that

propose that employees' assessments of what is and is not fair depend on their expectations about organization procedures. These expectations will be shaped by their individual preferences, their organizational experiences, and their moral and ethical beliefs.

Regulating Costs and Making Trade-Offs

The necessity of regulating costs is a fact of life in all organizations. Financial status and pressures from competition or funding sources force organizations to make choices about the amount of money that can be allocated to technology, capital and material investments, and human resources. Trade-offs must obviously be made. Whether they are couched in terms of an inducements-contributions exchange between employee and employer, or simply as keeping an eye on the budget, trade-offs must also be made among multiple human resource systems (selection, training, and so forth) and their objectives. Ideally, organizations try to meet their overall human resource objectives as best they can given cost constraints. Pay system objectives and the policies and plans adopted to meet them are no exception to this give and take.

An organization's decisions about whether to adopt a pay for performance policy and, if adopted, the type of plan to use are, in principle, subject to assessment of trade-offs among performance, equity, and costs. In practice, these assessments have been notoriously difficult to make (Cascio, 1987). Nevertheless, economists have developed models of the basic performance/cost trade-offs and some of the contextual conditions that influence them. Brown's (1990) study of firms' choice of pay method provides a summary of many of these models. He proposes that a firm's choice among plans basing pay increases on seniority or across-the-board criteria, merit plans, or piece rate (individual incentive) plans would depend on its assessment of each plan's ability to accurately measure employee performance and the costs of implementing the plan in the firm context. By design, piece rate plans, tied to specific, quantitative measures of employee productivity, are viewed as the most accurate of the three alternatives. Merit plans, tied to supervisory judgments about employee productivity, are the next best alternative in terms of accuracy. Standard rate plans, in which pay increases are tied to seniority or across-the-board criteria, are considered the least accurate alternatives.

The costs of actually implementing and monitoring each plan so as to reap the benefits of accurate performance measurement vary with firm context. Brown describes several contextual variables that many economists have predicted will influence these costs: the organization's size, its occupational diversity, the demands its technology makes on job structure, skill variation and quality versus quantity measures of performance, the organization's labor intensity, and the degree of unionization in the organization, industry, or sector. In general, the less the occupational diversity and the less complex and varied the job

structure and skill demands, the more appropriate the quantitative measures of performance. The higher the labor intensity, the less costly it will be to implement and monitor piece rate plans and still maintain the benefits of their accurate measurement. As occupational diversity increases, job structure become more complex, skill demands more varied, and quality measures of performance more important; as labor intensity decreases, merit plans may represent the best trade-off between accuracy of performance measurement and cost. Brown proposes that unionization may be the best predictor of a firm's adoption of seniority or across-the-board plans. He also suggests that, in some firm contexts, job complexity and interdependence will make measurement of individual performance so difficult that only group-level measures will be accurate. He does not, however, speculate about the organization conditions that would make group plans the cost-effective choice, and we know of no economic models that do.

Brown finds support for most of his predictions about the relationships between firm context and choice of pay plans. His study focused on manufacturing firms and production workers. We can only speculate that these predictions might be applicable to professional and managerial jobs and a firm's choice of individual bonus (based on mostly quantitative measures), merit, or seniority or across-the-board pay increase plans. A simulation study by Schwab and Olsen (1990) suggests that, in firms with highly developed internal labor markets and in managerial and professional jobs, supervisory estimates of individual performance used with conventional merit plans may provide a higher level of accuracy for the cost than previously thought. One simulation, however, is not enough to enable us to generalize about performance and cost trade-offs for management and professional jobs.

Economic models provide some conceptual basis for describing the potential trade-offs between performance and cost that an organization faces in choosing a pay increase policy and selecting pay for performance plans. We have no similar conceptual foundation for potential trade-offs between fair treatment or equity and costs. It seems reasonable to think that contextual arguments about these trade-offs could also be made. That is, the costs of ensuring that different types of pay for performance plans are viewed as fair and equitable will be influenced by firm context (Milkovich and Newman, 1990). However, the arguments for cost and equity trade-offs quickly become complicated when multiple organization stakeholders are considered. For example, when organization conditions all favor the use of individual incentives, investments in such procedural protections as appeals may be lower than under merit plans because it is easier for employees to accept quantitative performance measures as fair. Yet unions and associations often consider individual incentives plans unfair unless they are involved in the development of individual performance measures and in monitoring when measures should change. Some organizations

may consider that the costs of union participation cancel out the benefits from individual incentive plan use.

Our discussion of pay for performance plan costs and trade-offs has thus far dealt with the indirect labor costs that might be associated with plan design and implementation. There are, in addition, the direct labor costs that merit, individual, and group incentive plans like gainsharing and profit-sharing pay out in increases. It has often been claimed that individual and group incentive plans that do not add payments into base salaries will, over time, make an employer's direct labor costs more competitive. These claims, however, depend on many other factors, such as the employer's competitive wage policies and tax treatment of these variable payments. They also do not consider the potentially high indirect costs associated with successful individual and group incentive plan design and implementation. To date, no research has convincingly supported these claims (see Mitchell et al., 1990).

In summary, the research on cost regulation and the cost-benefit trade-offs associated with pay for performance plans is sparse and limited to production jobs and manufacturing settings. The research available does suggest that certain contextual conditions believed to reflect indirect labor costs are associated with organization decisions about adopting a pay for performance policy and selecting among merit, individual, or group incentive plans. The more contextual conditions depart from those considered most cost-effective in the implementation of individual incentive plans (structured, independent jobs, low occupational diversity, high labor intensity, and so forth), the more likely it is that merit or group plans will be considered. We have no evidence that any particular pay for performance plan is superior to another or to no pay for performance plan in regulating direct labor costs.

There is no research on cost and fairness or equity trade-offs, so the most precise summary we can offer is that we believe they exist. In adopting a merit plan or any other pay for performance plan, organizations should consider the likely equity perceptions of their various stakeholders, the process and procedural changes that might be required to improve them, and the resulting costs (economical, political, and social) of making those changes.

PAY FOR PERFORMANCE: RESEARCH FINDINGS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

Organizations have multiple objectives for their pay systems; they want them to attract, retain, and enhance the performance of successful employees, be perceived as fair and equitable, and help regulate labor costs. Our review of research on pay for performance plans was organized around these objectives, and the conclusions we have drawn from it have implications for federal policy makers' decisions about pay for performance for federal employees and, specifically, the use of merit pay plans. The committee's task did not extend

to any detailed analyses of the federal work forces and working conditions, so we cannot discuss research implications exhaustively or specifically. We can, however, discuss general implications.

Although virtually no research on the performance effects of merit pay exists, we conclude by analogy from research that examines the impact of individual and group incentive plans on performance that merit pay plans could sustain, and even improve, individual performance to the extent that they approximate the ideal motivational conditions prescribed by expectancy and goal-setting theories. There are some features of merit plan design that depart from these conditions, namely the use of less specific, less quantitative measures of performance (typically performance appraisal measures) that employees may find unclear and thus undoable, and the relatively small pay increases that are added to base salary. Employees may view such increases as too small to warrant additional effort, and their addition to base salary may make them seem less linked to performance.

However, organizations can and do take steps to strengthen the motivational impact of merit plans. For example, they can emphasize joint employee-supervisor participation in setting performance goals, thus increasing employee understanding about what is expected. They can emphasize the long-term pay growth potential offered under a merit program, thus making each pay increase seem more meaningful. This suggests that performance appraisal formats that allow some give and take between employees and supervisors, that make investments in training managers and employees in how to jointly set clear performance objectives, and that implement pay communication programs stressing the links between merit payouts, individual performance, and long-term pay growth could enhance the performance improvement potential of federal merit programs. The research on performance also led us to conclude that merit pay plans might best be adopted under certain contextual conditions. (Group incentive plans such as profit-sharing or gainsharing might also be considered, but our focus here is on merit plans.) There is evidence that, when jobs are complex, require work group cooperation, and are undergoing rapid technological change, employees are less likely to find specific, quantitative measures of performance—such as those typical of individual incentive plans—acceptable. There is also evidence that when the organization is facing economic pressures and reduced growth, tying relatively large payments to performance—as is more common of individual and group incentives—is especially threatening to employees. Moreover, the research suggests that when individual incentive plans are adopted under these conditions, they are often associated with negative consequences, such as employees' ignoring important aspects of their jobs, falsifying performance data, and actively restricting work group performance by ''punishing" high performers.

The federal government obviously represents a diverse set of job and organization conditions, and individual agencies face different economic pressures

and growth projections, but when jobs are complex and require work group cooperation (as is true of many professional and managerial jobs), and when there are significant economic and growth constraints, merit plans may deliver some of the individual performance improvements associated with individual incentive plans, yet have fewer of the negative consequences. The emphasis on the importance of context in organizational decisions to adopt different types of pay for performance plans also implies that an organization as diverse as the federal government might adopt several types of pay for performance plans (merit, individual, or group incentives) or, in some agencies, no pay for performance plans, depending on its agency-by-agency analysis of context.

Although the research on cost regulation and the cost-performance trade-offs associated with pay for performance plans is sparse, it is consistent with the research on performance effects in that both support the importance of contextual conditions in an organization's decision to adopt different types of pay for performance plans. It suggests that firms will adopt merit plans (or perhaps group incentive plans) when their occupational diversity, job complexity, and labor intensity are higher than would be ideal for individual incentive plans such as piece rates. Though piece rates offer the most potential for accurate performance measurement (and are thus the best indicator of actual individual performance), the cost of successfully implementing them under these organization conditions might be prohibitive. Merit plans offer the next best level of accurate individual performance measurement at a reasonable cost.

This research also suggests that firms that are heavily unionized tend to adopt seniority-based or across-the-board pay increase plans, presumably because unions are opposed to merit plans and this increases the cost of their adoption. The federal government may face higher costs in implementing merit plans than less unionized organizations.

There is no research that examines the relationship between different pay for performance plans and an organization's ability to attract and retain high-performing employees. We know that pay influences employees' decisions to join and to stay in an organization, but we cannot disentangle the influence of overall pay—let alone pay for performance plans—from all the other inducements (working conditions, promotions, job security, etc.) the organization has to offer. This suggests that the federal government consider the entire work experience offered to employees in its efforts to attract and retain the best performers; it should probably not expect a merit pay program alone to have a substantial effect.

Like the research on employee attraction and retention, research on fairness and equity does not allow us to distinguish among different types of pay for performance plans. Our conclusions from this research do, however, have some implications for an organization's adoption of pay for performance plans. First, the research suggests that there are different beliefs about how pay increases should be allocated—pay for performance, seniority, across the board, etc. The fact that these different beliefs exist suggests potential problems

for organizations like the federal government that are trying to change their allocation policies. Since increases are seldom doubled or denied, it appears that, in practice, the federal government used an automatic step increase policy for years. Although survey data indicating wide support for merit pay exist, a sizable portion of the work force may view the automatic step system as most fair and will thus be dissatisfied with any pay distributions based on performance criteria (Advisory Committee on Federal Pay, 1990). Managers who try to implement a pay for performance policy in this situation will be strongly tempted to manipulate pay for performance plans to maintain the status quo.

At the same time, the research suggests that organizations investing in measures to assure employees about the fairness of the procedures surrounding pay for performance plan design and implementation can positively influence pay satisfaction, perceptions of pay fairness, and employee trust and commitment. In application to merit plans, certain procedures would be included: providing employees with information about the way appraisal works, training managers in conducting appraisals, employee participation in setting performance objectives, and channels for appealing ratings and pay increases. Procedural fairness is also a concern of other organization stakeholders, such as regulatory agencies and unions or associations. When employees believe pay for performance procedures are fair, managers administering these programs may face less hostility, despite employee dissatisfaction with ratings or increases. We know that the federal government has many procedural protections in place for its employees, but given the historical precedent for seniority-based pay increases, the representation of unions and associations in the federal work force, and the regulatory and public scrutiny that agencies face, an examination of how those procedures are operating and a focus on employee perceptions of fairness may be an important aspect of merit pay reform.

We began this chapter by observing that the pay systems of organizations have multiple objectives reflecting the various interests of multiple stakeholders. An organization's ability to meet those objectives will not depend on pay for performance plans alone. It depends on many organizational factors including other pay decisions, its human resource systems, its job structures, its management style, its work force, and its institutional goals. It will also be influenced by external conditions such as economic pressures, unionization, and pressures from regulations and public opinion. Switching to a pay for performance policy, adoption of a particular pay for performance plan, or change in current plans is unlikely to help an organization meet and balance its pay system objective unless the changes make sense within the total pay system, the personnel system, and the broader organizational context. No one pay for performance plan will be right for every organization.

The implications of the federal context for merit plan adoption are taken up in Chapter 7. We turn next to a review of performance appraisal and pay for performance practices in the private sector.