15

Confronting Special Implementation Issues: Translating the Institute of Medicine Report Strategy Beyond Medicare

James S. Roberts

My responsibility is to discuss the translation and deployment of the ideas contained in the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 1990) report beyond the Medicare program. To do so I need to start by noting what I think the report says: the major themes, the directions it would take us, and the objectives it establishes for the next step in the evolution of approaches to improving the quality of care in this country. Although I will not comment on the suggested restructuring of the Peer Review Organization (PRO) program, I will say that it is nice to see "MQROs" back.1 Much of what we were trying to do early in the 1970s with the EMCRO program is reflected in this report. I hope that this version will make it further down the road than our earlier model did.

The proposed restructuring of the PRO program represents the IOM committee's suggestion for implementation of its ideas within the context of the Medicare program. My charge is a different one. When one goes beyond the Medicare program, the evidence is clear that other payment programs will use a variety of means to address the ideas contained in the report. PROs will not be the vehicle that will be used uniformly.

MAJOR THEMES OF THE INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE REPORT

So my task is to concentrate on pursuit of the themes of the report—not on the organizational form in which the pursuit will occur. Let me start by

discussing the report's basic themes. Understanding these themes will help us grasp the deployment challenge.

Antecedent Processes and the Outputs of Health Care

The overarching theme of this report is a bit hidden. Although the point is not brought together in one place, the report strongly emphasize that the outputs of health care are the combined results of several important antecedent processes. Thus, outputs for a population of patients, or for an episode of care, are dictated not just by clinical care but by a much more complex interplay of practitioner, patient, and organizational factors and by a variety of forces external to the organization.

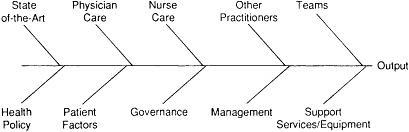

Figure 15.1 depicts this reality. In the quality improvement world, this is called a "cause and effect" or "fish-bone" diagram. It is used to understand the many causes of a measured effect. Using any measure of output one wishes to explore—a patient outcome, a change in functional status or psychological status, mortality rates, morbidity rates, a measure of value (cost and quality)—at the head of the fish-bone diagram, one can easily identify the many potential determinants of these outcomes.

As the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (Joint Commission) and health care organizations have worked with this tool it has become clear (as noted in Figure 15.1) that the activities of practitioners, governing boards, and managerial and support staff all have a potentially powerful influence on patient outcomes.

At the interface between these internal influences and the external world is the manner in which the results of clinical research are synthesized and disseminated to health care practitioners and then used to influence day-to-day practice. Here we are talking about the work of the research community in conducting and reporting clinical and health services research; the professional associations in their work efforts to develop and disseminate useful practice guidelines; and the educational community in its use of continuing education mechanisms. All have a critical, though often unmeasured, impact on quality. "Health policy" (Figure 15.1) is broadly construed to include such matters as the availability of insurance coverage and the structure of insurance plans, the imposition of nonproductive standards by accreditors and by government, the level of resources made available to health care organizations, the use of price-based selective contracting, the stimulation of aggressive competition within local markets, and professional liability law and practice. All have a potentially powerful effect on the outputs of the system. So government, accrediting organizations, unions, insurers, and purchasers of care all influence outcomes.

Before leaving my discussion of this overall theme, let me return to the health care organization. Most believe, or at least most act as though, the

Figure15.1 A "fish-bone" diagram of potential determinants of organizational outputs as they relate to quality improvement.

exclusive determinant of quality is the physician. It is as if mortality rates and complications are caused solely by the presence of (or lack of) physician knowledge and skill. Such is not the case. Outcomes are also determined by nursing care, by the work of other practitioners, and by the ability of practitioners to work together in teams. The quality of support services has been seen principally as an issue of safety and quality control of test results. Largely ignored are the important interactions that should go on between practitioners and support services staff concerning the specific nature of the patient's problems and the precise type of service that best meets those needs. For the most part, quality evaluations have ignored the important roles that boards and the management of health care organizations play in the ability of the organization to produce desired outputs.

The message in this conceptualization is that we are all in this quality business together. We have, in fact, a shared responsibility and accountability for the quality of care. So rather than painting the quality scene as one in which external organizations tell hospitals and doctors what they have to do, and rather than these same outside agencies demanding a variety of data from health care organizations or from doctors and then making judgments about performance, the notion here is that we are all part of the problem and, thus, must all be part of its solution.

The production of appropriate, efficient, and effective health care must become the combined effort of everyone represented in Figure 15.1. It is both a shared responsibility and a shared accountability. All of us—accreditors, government, insurers, businesses, patients, practitioners, and health care managers—must understand that we are accountable for what we do. If the outputs of health care are not at a level that is desired, the cause is unlikely to be confined to inadequate hands-on care; it may also be poorly designed health care plans, ill-conceived standards of care, misguided management, or the poor or inadequate use of practice guidelines.

By focusing on factors beyond the practitioner, I do not mean to excuse

poor care. Government and accreditors should have tough requirements and should apply them well. They must, however, be grounded in the best available information and must facilitate good care. Nor am I saying that corporations should not design their health benefits plans in a businesslike fashion. They have to; that is a fact of life. What I am saying is that the decisions these outside agencies make must reflect careful attention to their potential impact on patient outcomes—the effect that these decisions have on the level of performance of the health care system. That, it seems to me, is the overarching theme of this report.

Seven Derivative Themes

In addition, several other themes are largely derivative of the first. They are summarized in Table 15.1.

The first is the absolute need to rekindle professional instincts for constant improvement. Here I do not confine myself to physicians. The same imperative exists for nurses, other health care practitioners, and managers of health care organizations. Quality assurance, as currently performed, simply does not make sense to most people involved in the day-to-day delivery of health care. It has deadened the natural interest in and inclination toward constant learning and fact-based improvement in performance.

The second is that we need to focus review activities on quality. Much attention was given to this point during the conference on which this monograph is based. I simply echo the point and emphasize the importance of focusing on the use of outcome measures as windows into weaknesses in the design and performance of key processes.

Third, as we address quality we must recognize the importance of continuity of care—the coordination of care among practitioners and departments within organizations and across organizational boundaries within a geographic community—and of educating the patient and his/her family and of their engagement in clinical decisionmaking.

TABLE 15.1 Key Themes of the Institute of Medicine Report

|

• Rekindle the professional instincts for constant improvement • Focus review activities on quality • Recognize the importance of continuity and of patient and family involvement • Address the critical, if currently hazy, link between processes and outcomes • Build a better substrate for evaluation and improvement • Foster improvement in internal quality assurance and quality improvement • Enhance coordination and communication among external organizations |

The fourth theme is the need to address the critical but oftentimes hazy link between processes and outcomes of care. If you think about the various "bones" of the fish-bone diagram, you should see that each represents a series of processes. We need to understand how those processes are linked to desired (or undesired) outcomes. The IOM report suggests that they be addressed both at a national level, through better and more targeted research and the development of practice guidelines, and within health care organizations. As Caldwell (1991) discusses the latter point, each organization should understand how its performance of key processes influences the outcomes achieved by the patients it serves.

Fifth, I would add that there must be a better understanding of the regulatory, accrediting, and insurance processes as they play through to patient outcomes, partly through a better foundation for evaluation and improvement. Often ignored, these evaluative processes can either stimulate or obstruct the provision of appropriate, effective patient care. The organizations involved in such activities must do much more to align their objectives and requirements with those of well-intentioned health care organizations. They must also do more to bring order to the current cacophony of demands they make on health care organizations.

Sixth, we must foster substantial enhancement in internal quality assurance and quality improvement mechanisms. Any external organization that does not have this as one of its principal priorities is abdicating its responsibilities. Such organizations are part of the problem, not part of the solution. Seventh, there must be better coordination and communication among the many external organizations. Those who demand things of health care organizations have an obligation to get their own act together among themselves.

These, then, are the themes of the IOM report. Now I want to talk about how to take those good ideas and make them real. I will do so by focusing first on the health care organization and what it needs if these suggested changes are going to become operational.

NEEDS OF HEALTH CARE ORGANIZATIONS

The needs of health care organizations fall into the categories shown in Table 15.2. First they need models for the creation of positive, improvement-oriented internal cultures. There is a lot of talk about the need to change the way we think about quality in health care. The most compelling theme is the need to create a more improvement-oriented culture. Yet it is not clear how one makes the transition from the current punitive atmosphere to a much more positive one. Expressing the need for such a change does not necessarily turn on the light bulb. How do you get a fast moving train onto a different track? We need some models for this switch and, fortunately, some are being constructed. They are developing very organically day after

TABLE 15.2 Needs of Health Care Organizations

|

• Models for the creation of a positive, improvement-oriented internal culture • Synthesized state-of-the-art information and models for, or indicators of, their use • Practical models for process description, measurement, and improvement • Public policy that more clearly differentiates "tail-of-the-curve" practice from the more universal need for continual improvement • Coherent and coordinated external expectations and improvement-focused use of information |

day within a growing number of enlightened health care organizations. We need to learn from the experience of these leaders.

Health care organizations also need well-synthesized state-of-the-art information and, most importantly, guidance on how to translate it into day-to-day practice. Whether one calls such information "practice guidelines," "clinical parameters," "branching logic trees'' (or "thickets" as one conference participant put it), there is a lot of it around. Although we certainly need such material, the most critical obstacle is the lack of a practical understanding of how to use it. How do we translate information contained in practice guidelines into improved patient care? How do we use continuing education programs and quality improvement programs to assure the effective incorporation of such information?

A key part of the strategy must be well-conceived indicators that tell whether such material is being used and used well. The objective is not a punitive one. Rather we must measure whether guidelines are being used, and if not, why not? Are they unclear, incomplete, irrelevant? Are there weaknesses in implementation strategies?

An additional need is for practical models for process description and improvement. If, as noted earlier, process knowledge is the key to improved outcomes, we must give organizations models for describing their performance of these key processes. How do you take the flow of medication use or the care of the trauma patient across departments and professional groups and describe it for yourself, for your organization? What measures do you use to judge whether these processes are effective? How do you use outcome measurement as a window into process improvement? Organizations know they have problems; they have reams of data that tell them that they are weak, but they literally do not know what to do next.

Health care organizations also need public policy that clearly differentiates tail-of-the-curve practice from the more universal need for continual improvement. As I noted earlier, health care organizations deserve coherent and coordinated external requirements and improvement-oriented use of

information—not more information to do more sanctioning, but better information to prompt improvement.

STRATEGIES FOR DIFFUSION

Gain Acceptance of Shared Responsibility

Beyond meeting these needs of health care organizations, what strategies must be followed if the themes of the IOM report are to have their maximum impact? I believe three strategies must be pursued. The first (Table 15.3) is to gain understanding and acceptance of the notion of shared responsibility and shared accountability discussed earlier. Imagine, for example, collaborative efforts that focus on a key output, by using the mechanism of placing that output on the far end of a fish-bone diagram and then engaging in a collective examination of the various roles that the actors on the branches of that diagram play in either fostering high levels of performance or obstructing high levels of performance.

Might such an exercise (possibly in the context of a community-based examination of its health care system) improve the manner in which we deal with each other and modify the current finger-pointing nature of such efforts?

Might it also be instructive to take this approach with current population-based research studies? Consider, for example, large-scale data base studies with shared responsibility as the paradigm. That is essentially the route, it seems to me, that John Wennberg and his colleagues are taking with their prostatectomy studies. It is the concept that underlies the comparisons of the New Haven and Boston health care systems. These studies raise important questions about how these communities operate their health care systems.

Should we convene some conferences that have "shared responsibility and accountability" as the theme and explore the practical ramifications? How would the new mindset change the data demands that accreditors, that government, and that businesses are expecting of health care organizations? What would it do to quality assurance requirements? How would insurance coverage determinations change? The practical ramifications of this idea

TABLE 15.3 Gain Acceptance of Shared Responsibility

|

• Case studies of the determinants of patient outcomes • Reanalysis of population-based studies using shared responsibility as the paradigm • Conferences that posit this theme and explore its practical ramifications • Identification and celebration of models |

might be played out profitably in a conference or two. Finally, we need to identify and celebrate models. There are models—in Kingsport, Tennessee, for instance, and Rochester, New York. These experiements and models ought to be held up for praise and evaluation.

Remove Major Barriers

The second strategy (Table 15.4) is the removal of barriers. Without going too far, we need to temper expectations for constant perfection or the assurance of quality. What we are talking about here is quality "improvement" not quality "assurance"; some say we are talking about "value" improvement. Maybe the common ground—the shared interest of all major actors—is continual improvement in the value of health care, the value we get for the money we invest. We need to refocus leadership attention on fostering constant enhancement in value.

We need to increase and refocus health services and clinical research and development (R&D). This is a fundamental recommendation in the IOM report, although it does not emphasize sufficiently the need to devote much of this R&D to the practical needs noted in Table 15.2. It would be instructive to compare this list with the research agendas of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, the Joint Commission, and individual health services research centers to examine how well they match. Does this research answer these needs? If, as I suspect, the match is inadequate, we must reorder our research priorities in the context of the real-world needs of those who have to take the IOM themes and operationalize them.

Next, barriers that are created by aggressive competition need to be identified. I am not against competition, but I can tell you that many health care professionals are distressed by its effect on their ability to share experiences and to learn from each other. Before the recent push for significant competition within local markets, many important community-based professional

TABLE 15.4 Remove Major Barriersa

networks existed. The engineers, the quality assurance people, the chief executive officers, the medical staff leaders, the nursing directors, and others would get together in informal ways and share experiences, exchange ideas, celebrate successes, and discuss common problems. Now these colleagues are seen as enemies. They are literally afraid to meet with each other and to share these ideas with the ''bad guys." There is a chill on basic information sharing, and I think that is unfortunate.

Finally, we need to shrink the sanctions net. We catch lots of dolphins in this net; it needs to be narrowed. At the same time, we need to expand the search for improvement opportunities.

Develop and Disseminate Models

The third strategy is shown in Table 15.5: the development and dissemination of models. Health care organizations are starving for good models, particularly those that have undergone real-world testing. We do not need theoretical models; we need operational models. Important activities are under way at national, regional, and local levels and within individual health care organizations. It would be helpful to have a resource center that systematically gathered these models and disseminated them. We must hear about both the successes and the failures. Nobody likes to talk about his or her failures, but they are very instructive, maybe more useful than the success stories. Most of these stories will not appear in refereed journals as they now operate. New sections of such publications should be created, and educational conferences focused on real-world needs would be helpful.

TABLE 15.5 Develop and Disseminate Models

|

• Health care organizations are starving for models • The need is for approaches that have received real-world testing • There are activities under way in all areas of necessary change • Both successes and failures must be made known • This is not always the material sought by refereed journals |

Enhancing Coordination

Finally, it is important that we enhance coordination among external actors, such as government agencies, PROs, accreditors, insurers, and the long list of other folks that are external to health care organizations (Table 15.6). One way to make that happen is for everybody to create it as an expectation. All of us listen to the constant expectations of those we affect—or we should. An area the Joint Commission is beginning to explore

TABLE 15.6 Enhance Coordination Among External Agencies

|

• Keep expressing this as an expectation • Provide practical information on the implications of fragmentation • Identify and strengthen current models • Use existing forums to foster coordination • Identify statutory, philosophical, and other barriers and remove them • Drop stereotypes and destroy pigeonholes |

involves the extent and implications of fragmented, external requirements. Hospitals now have 10, 20, 30, even 50 requests for a significant volume of data concerning various segments of their patient population. What is the cost of answering these demands? If data are defined differently, how much waste does this create? We need to improve on existing forms of coordination among external agencies, and new forms need to be created.

The Institute of Medicine, the Joint Commission, business groups, and government each have forms that they could use to talk about these IOM themes and their implementation. We need to identify statutory and other barriers to rational action. I would particularly comment on the first recommendation of the IOM report.2 I am concerned about statutorily giving to any one group in this system the "responsibility" for quality. It cuts against the basic notion of shared responsibility—that particular recommendation ought to be considered carefully.

CLOSING REMARKS

Let me close by saying that if quality is to be enhanced, we must drop stereotypes and destroy all these pigeonholes into which we tend to put each other. This field is awash with stereotypes. Doctors are put here; hospitals are put there; governments are put in that pigeonhole; accreditors are put in yet another one. These stereotypes chill innovation and make coordination difficult. If government and professional leaders are prevented by these destructive stereotypes from exploring more rational, integrative,

innovative approaches to quality, then we all lose, and the good ideas contained in the Institute of Medicine report simply will not be realized.

REFERENCES

Caldwell, C. Organization- and System-Focused Quality Improvement: A Response. Pp. 37-43 in Medicare: New Directions in Quality Assurance. Donaldson, M.S., Harris-Wehling, J., and Lohr, K.N., eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1991.

Institute of Medicine. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Lohr, K.N., ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990. (See especially Volume I, Chapter 12.)