9

A Patient Outcomes Orientation: The Committee View

Albert G. Mulley, Jr.

Others have reported the general findings and conclusions of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee to Design a Strategy for Quality Review and Assurance in Medicare (IOM, 1990; Schroeder, 1991). The vision of a new quality assurance system for Medicare that the committee shares will require new directions, including increased emphasis on programs to enhance professional responsibility (Cooney, 1991), better systems to assure quality and make use of clinical practice as a source of information (Mortimer, 1991), and a sharper focus on health care decisionmaking (Griner, 1991).

The purpose of this paper is to make the committee's case for a shift from a provider and process orientation to a patient and outcome orientation. I will argue that this element of our overall strategy is central and, perhaps, the most critical to its success. Lest you think that we have been naively swept along with the current enthusiasm for outcomes, I will also share our concerns about the complexities and potential pitfalls of a quality assurance system that relies heavily on outcomes.

PROCESSES, OUTCOMES, AND PATIENT CHOICES

The argument for more emphasis on outcomes is closely related to those for enhanced professional responsibility and patient involvement in decisionmaking. Simple building blocks can be used to demonstrate these relationships and then to broaden the argument to questions regarding the role of outcomes measurement in quality assurance. We will define "outcomes" precisely and relate them not only to the structure and process of health care, but also to the wants and needs of individual patients.

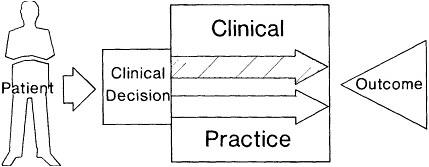

Figure 9.1 provides a caricature of how a patient interacting with the health care system produces an outcome. The patient might be bothered by

symptoms associated with prostate disease, a clinical example that has been studied extensively (Wennberg et al., 1987; Barry et al., 1988; Fowler et al., 1988; Mulley, 1989, 1990). The figure could also represent a patient with chronic angina, disabling osteoarthritis, or any number of other conditions. Symptoms that impair the quality of life prompt an encounter with the health care system. The box represents the structural elements—those that relate to the capacity of the system to deliver quality health care. The arrows represent alternative processes of care, that is, what may be done to and for the patient. The outcome is represented by a triangle, each side defined by measures of physical, psychological, and social functioning.

Seldom is only one process of care available to, or even appropriate for, a particular patient with a particular problem. There are choices. For the patient with prostate disease, it may be a choice among prostatectomy and watchful waiting; for the angina patient, a choice among bypass surgery, angioplasty, or medication; and for the patient with arthritis, a choice between joint replacement and anti-inflammatory drugs.

The manner in which these choices are made deserves careful scrutiny. Recognize that patient choice is central to the phenomenon of practice variation and to the IOM committee's concerns about underuse and, particularly, overuse of services as significant quality problems.

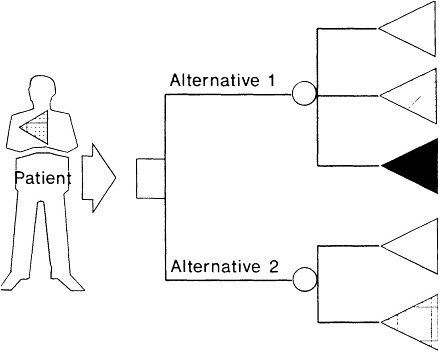

Consider the decision of the man with benign prostatic hyperplasia, which is represented in its simplest form in Figure 9.2. Quality of life has been diminished by bothersome urinary symptoms. The patient faces, with the help of his physician, a choice between two alternative treatment strategies. The first alternative, surgery, is a bit risky: the eventual outcome is uncertain and, although there is a good chance that it will produce the most valued outcome, there is also a chance that it will produce the outcome that is least valued, a complication leading to serious morbidity or even death.

Figure 9.1 A patient faces a clinical decision about the process(es) of care most likely to produce desired health outcomes. See text.

Figure 9.2 A simple representation of the decision faced by the man whose quality of life is impaired by symptoms of prostate disease. The square node represents a choice. The round nodes represent chance events. The triangles represent outcomes. See text.

An intermediate outcome, such as impotence or incontinence following surgery, is also possible. The second alternative, watchful waiting, is less risky: the only possible outcomes are the most valued—symptom relief—and the patient's current health state. Note that some uncertainty about the outcome following either choice is inevitable. Therefore, a good decision for a particular patient can produce a bad outcome, and a bad decision can produce a good outcome. This clearly presents some dangers for those who would use outcomes to measure or monitor quality. This inevitable uncertainty also explains the term ''increased likelihood'' in the committee's definition of quality.

INFORMED DECISIONMAKING

What do patient and doctor need to make this choice? First, they need to know how likely each of these outcomes will be if alternative 1 or 2 is

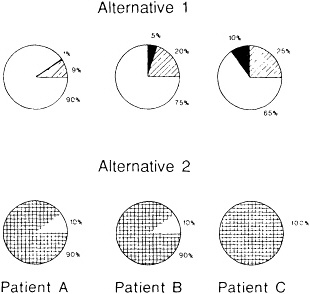

chosen. These probabilities can be depicted as pie diagrams (Figure 9.3). For the hypothetical patient who faces the decision (Patient A in the figure), alternative 1 has a 90 percent chance of producing the most valued outcome, a 1 percent chance of operative death, and a 9 percent chance of impotence and/or incontinence. Alternative 2, which looked so good without probability estimates, looks less promising with them: the odds are 9 to 1 that the health state bad enough to bring the patient to the doctor will persist. It can be said that knowledge is power because it confers the capacity to predict. Accurate estimation of outcome probabilities as represented in these simple pie diagrams captures the essence of professional knowledge relevant to the practice of medicine.

Where does this knowledge come from? The most obvious source of probabilities is the collective experience of previous patients. This constitutes the "clinical experience" of the provider that is so important to "clinical judgment." There are, however, real problems with this source of information. First, there are problems with the way clinicians characterize individual patients. Second, clinical practice is not standardized: interventions are not carefully defined and uniformly applied. Third, there is no routine mechanism to define outcomes with the appropriate level of detail or to aggregate and organize the information that could be derived from collective clinical experience. Without such systematic aggregation and analysis, the cognitive heuristics that we all use routinely may mislead the clinician's unaided intuitive estimates of outcome probabilities.

Recognizing these problems, the profession relies heavily on published clinical research when it is available. The randomized trial is the standard against which other clinical studies are measured. We can learn something about the complexities of using outcomes for quality assurance by considering the methodological requirements of valid research. Information about patients entering the trial is systematically collected. The group is made homogeneous by applying exclusion and inclusion criteria. The alternative interventions are carefully defined and their elements carefully segregated. Outcomes are carefully catalogued. The scientific requirements of research designed to determine the effectiveness of one intervention relative to another, which is nothing more than the relative outcome probabilities, include similarity of the initial states, integrity of the interventions, and similarity of detection or measurement of outcomes.

Even when well-conducted randomized trials are available, problems arise in using the results to estimate outcome probabilities. Clinicians may forget about real differences between the circumstances of the clinical trial and the circumstances of clinical practice. They may also forget about the patients excluded from the clinical trial. These exclusions are not trivial, commonly representing more than 90 percent of the patients for whom the intervention would be used in practice.

Figure 9.3 The pie diagrams represent different outcome probabilities for different patients.

The exclusions are important because different patients face different outcome probabilities even when the care rendered is identical. This is illustrated in Figure 9.3 by the three pairs of pie diagrams, each representing different outcome probabilities for a hypothetical patient. Clearly, a choice made by or for one of these patients should be based on probabilities derived from the experience of similar patients. Any inference about the effectiveness of a particular intervention must adjust for different mixes of patients with different outcome probabilities. Any inference about the quality with which an intervention is delivered is equally dependent on such adjustment.

CLINICAL PRACTICE AS A SOURCE OF KNOWLEDGE

The IOM committee's proposed emphasis on outcomes can serve to make clinical practice a source of new knowledge that is very valuable to the professional and the patient. If we can effectively characterize patients by disease severity, comorbidity, and other variables that affect prognosis,

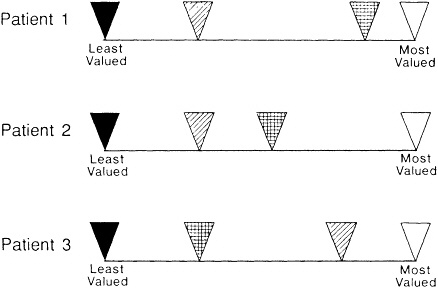

Figure 9.4 Three scales representing relative value of different outcomes for three different patients. See text.

if we can characterize the processes of care, and if we can measure outcomes and relate them, for each patient subgroup, to the alternative care processes used, then we can give providers and patients the information they need to make informed decisions.

This approach could dramatically improve our ability to estimate relevant outcome probabilities. The committee felt, however, that probabilities alone were insufficient. Whether the pie diagrams in Figure 9.3 represent probabilities of outcomes for a health care decision or a simple game of roulette, information about the likelihood of the outcomes must be accompanied by information about their relative values in order to be helpful to the person making the decision. Here is where the shift from a provider orientation to a patient orientation is most important and most challenging. This explains the reference to "desired health outcomes" in the committee's definition of quality.

The top bar in Figure 9.4 represents a scale on which we can register the value judgments of the hypothetical patient with prostate disease. It is anchored by the least and most desirable outcomes. The markings on the scale indicate that he prefers his current state to the one that would be imposed by a complication of alternative 1. This patient might, therefore, opt for the less risky alternative 2. The bottom two scales display different

value judgments for different hypothetical patients, similar enough to face the same outcome probabilities, but with different preferences. For the second patient, the same health state diminishes life's quality more; alternative 1 may be preferable despite the risks. For the third patient, alternative 1 would almost certainly be the best choice. The current health state is perceived as a serious hardship, and the state associated with a complication of alternative 1 is not.

PATIENT VALUES

We know that patients' subjective responses to the same health states can be very variable. Doctors, too, have variable responses that may or may not be systematically different from those of patients. Information of this sort is scarce, but the tools to gather it are increasingly available. It is necessary information if we are to provide a context for the patient trying to make a health care decision, or if we are to measure quality using a definition that specifies desired health outcomes.

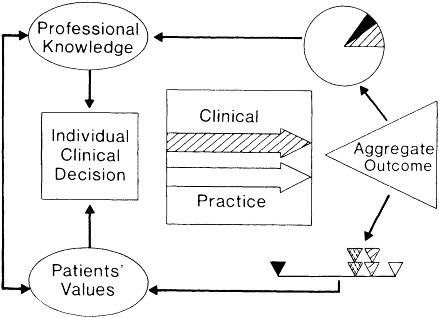

The conceptual model is illustrated in Figure 9.5. Aggregate outcomes

Figure 9.5 The role of aggregate outcomes in informing professional knowledge and patients' judgments about desired health outcomes.

serve as a source of information for the profession and patients, continuously improving the knowledge base on which decisions depend. Appreciate the pivotal role of outcomes: without outcomes, information most relevant to the patients' predicament and the providers' role is not captured. Without outcomes, therefore, professional knowledge may be disengaged from the decisionmaking process. Without outcomes, the patient orientation could be neglected.

OUTCOMES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE

Clearly, this model assumes professional responsibility and patient involvement, elements of quality assurance that the IOM committee would like to promote. Yet what about quality assurance? How would we avoid depending too heavily on a presumption of virtuous professional behavior?

We complicate the model by acknowledging that not all providers are alike. Structural aspects of care vary from place to place. There are subtle and not so subtle differences in the processes of care. One provider may be more or less reluctant than another to use an intervention for a certain class of patients. When systematic treatment differences among providers occur, the outcomes may differ. Consider how valuable information about such differences would be not only to a patient, who could be expected to prefer the provider whose outcomes are better, but also to providers. Well-in-tended providers who discover that they do not achieve the best outcomes learn how to improve their processes from those who do. In the absence of such cooperation, which might seem naive or foolish to providers given incentives to compete with each other, they might at least be stimulated to examine their processes and improve them.

Such outcome rates would be a central product of our envisioned quality assurance program. Stimulating and enabling providers to characterize their patients, define their processes, and measure their outcomes would be a central task of the proposed Medicare Quality Review Organizations (MQROs). The Medicare Program to Assure Quality (MPAQ) would provide support, including technical assistance, and oversight. These tasks will not be easy. Because the knowledge, skills, and systems are not widely available, we will have to get there incrementally and make strategic choices. We have said that we would begin with discrete conditions that generally require hospitalization, then include forms of care that substitute for inpatient care such as ambulatory surgery. We would then extend the approach to ambulatory care, nursing homes, and eventually, home care.

SUMMARY

The extended conceptual model can be described succinctly. Aggregate outcomes of care serve as a source of comparative information. That com-

parative information must be credibly adjusted for the differences in patients. Its principal use would be to inform decisions and stimulate internal examination and quality improvement among providers. That examination and improvement would focus on the processes of care. Policymakers would also benefit from the comparative rates and the information about what patients value. These decisionmakers can influence the capacity of the system to provide different kinds of care, dealing with the structural elements of quality in a way that reflects desired health outcomes. To foster an enhanced sense of professional responsibility, we would see providers as the primary consumers of this information, but we also recognize that not all providers will make good and timely use of it. We see the eventual public disclosure of carefully validated outcome rates that have been generally accepted as valid by the professional community as a powerful stimulus for providers to improve or leave the marketplace. We also see the timely release of positive outcome rates as a welcome positive incentive for providers. Finally, we see this approach as the one most likely to bring providers, patients, and policymakers to recognize their common as well as conflicting interests in quality.

REFERENCES

Barry, M.J., Mulley, A.G., Fowler, F.J., et al. Watchful Waiting vs. Immediate Transurethral Resection for Symptomatic Prostatism: The Importance of Patients' Preferences. Journal of the American Medical Association 259:3010-3017, 1988.

Cooney, L.M., Jr. More Professionalism, Less Regulation: The Committee View. Pp. 18-21 in Medicare: New Directions in Quality Assurance. Donaldson, M.S., Harris-Wehling, J., and Lohr, K.N., eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1991.

Fowler, F.J., Wennberg, J.E., Timothy, R.P., et al. Symptom Status and Quality of Life Following Prostatectomy. Journal of the American Medical Association 259:3018-3022, 1988.

Griner, P.F. Improved Decisionmaking by Patients and Clinicians: The Committee View. Pp. 48-53 in Medicare: New Directions in Quality Assurance. Donaldson, M.S., Harris-Wehling, J., and Lohr, K.N., eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1991.

Institute of Medicine. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Volumes I and II. Lohr, K.N., ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990.

Mortimer, J.D. Organization- and System-Focused Quality Improvement: The Committee View. Pp. 21-36 in Medicare: New Directions in Quality Assurance. Donaldson, M.S., Harris-Wehling, J., and Lohr, K.N., eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1991.

Mulley, A.G. Assessing Patients' Utilities: Can the Ends Justify the Means? Medical Care 27:S269-S281, 1989.

Mulley, A.G. Methodological Issues in Applying Effectiveness Outcomes Research to Clinical Practice. Pp. 179-189 in Effectiveness and Outcomes in Health Care.

Heithoff, K.A. and Lohr, K.N., eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990.

Schroeder, S.A. The Institution of Medicine Report. Pp. 7-14 in Medicare: New Directions in Quality Assurance. Donaldson, M.S., Harris-Wehling, J., and Lohr, K.N., eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1991.

Wennberg, J.E., Roos, N.P., Sola, L., et al. Use of Claims Data Systems to Evaluate Health Care Outcomes. Mortality and Reoperation Following Prostatectomy. Journal of the American Medical Association 257:933-936, 1987.