2

Managing the NIH AIDS Research Program

In the nine years since the epidemic of HIV infection and AIDS emerged, NIH has created a vigorous research program that has achieved several notable successes. Researchers have identified HIV as the viral agent, made progress in understanding the epidemiology, natural history, and pathogenesis of the disease, and developed several therapeutic and prophylactic drugs that are partially effective against HIV and some of the opportunistic infections and cancers associated with it. These advances, among the most rapid in the annals of medical history, attest to the underlying strength of American biomedical research and NIH responsiveness, once the agency was provided with resources to mount a major AIDS research program. Much remains to be done, however; the burden of AIDS-related disease continues to grow, and many important scientific and practical questions have yet to be answered.

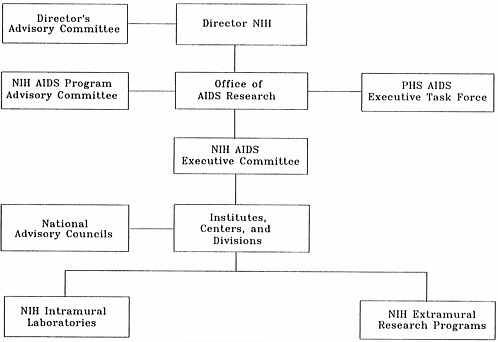

The challenges presented by HIV and AIDS are not limited to those involving actual research. NIH has also faced unprecedented management demands to develop, implement, coordinate, and evaluate a rapidly growing, complex set of AIDS research activities that now involve every NIH institute, center, and division. In response to rapid program differentiation and growth, NIH has evolved a special administrative system, based in the Office of its Director (OD), for coordinating and managing the AIDS research program. The overall NIH AIDS management structure is depicted in Figure 2.1.

As NIH ends a decade of rapid growth of its AIDS research programs, it is well to ask whether the management arrangements that worked during that period are appropriate for the 1990s and beyond. The agency's overall goal remains the same, that is, to achieve an understanding of HIV infection and related diseases so that they can be prevented, cured, or controlled through the development of new therapies, vaccines, and programs of behavioral change. What needs to be reviewed now are the adequacy and appropriateness of the structures and procedures NIH has evolved to ensure that (1) the most important scientific questions are being pursued and the highest priority programs are in place, (2) gaps in knowledge are filled and duplication of effort is avoided, and (3) generally, the multiplicity of activities being carried out by the various units and subunits of NIH add up to a coherent strategy. Such a reassessment should consider the changes needed in the current program structure as AIDS research matures and becomes more integrated with regular NIH activities. Reassessment is also needed as research advances and breakthroughs require reallocation of resources from existing to new programs (and perhaps from one institute to another) and time and experience indicate that some programs are more and some less successful than others. As the AIDS research enterprise matures, NIH must shift from an entrepreneurial

to a management mode of program operations. This shift will require strengthened management systems for planning, coordination, and evaluation in the NIH Director's Office.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

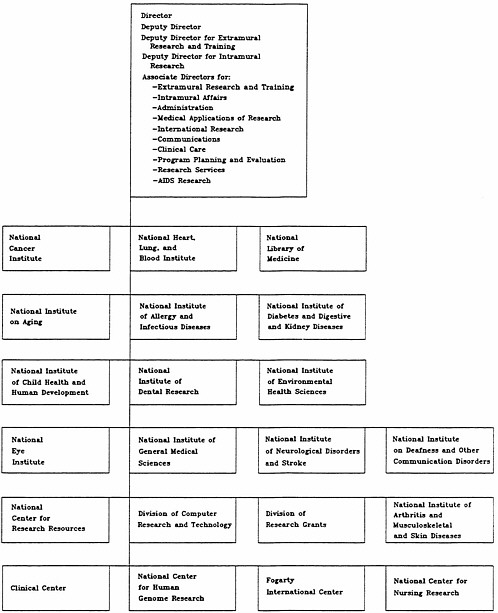

NIH is a highly decentralized organization, a structure appropriate to a basic research enterprise. The agency comprises 13 research institutes, 5 research centers, 2 divisions, the National Library of Medicine, and the Office of the NIH Director, all of which conduct AIDS-related activities (Figure 2.2). Organizationally, NIH is further decentralized by the separation of the grants review process from extramural program management. All research grant applications receive a first-level review for scientific merit by independent disciplinary study sections of extramural experts, after which the applications are sent to the appropriate institutes for decisions on funding. Organizational analysts consider this interplay between the categorical institutes and the disciplinary study sections to be the genius of NIH's organization: “The primarily disease-based institutes enable Congress to understand, appreciate, and support the research accomplishments of the institutes, and also to express concerns and priorities about the need for further research. The study sections, on the other hand, cut across institute lines and ensure that appropriate scientific talent and ideas are brought to bear on the problems” (IOM/NAS, 1984:1). As a result, NIH has been able to sustain high-quality research, address public scientific concerns, as defined by Congress, and support basic biomedical research on which future advances will surely depend. It is evident, however, that this decentralized structure is not designed to respond as swiftly and efficiently as a more hierarchical organization to situations that require a coordinated, agency-wide response.

Within this highly decentralized organization, the NIH director and a small staff are expected to provide leadership in the interplay between the public and the scientific community. They must also coordinate programs that cross institute lines (but not micromanage the research programs of the institutes) and oversee common housekeeping functions for the institution as a whole. In the case of AIDS, each institute manages its AIDS activities as part of its overall program, involving the institute's staff, senior leadership, board of scientific counselors (which oversees the intramural program), and national advisory council (which discusses policy and program issues, reviews program concepts, and approves each grant). In most cases, AIDS activities are carried out within the institute's regular organizational structure; only NIAID, because of the large size of its AIDS program (53 percent of NIAID's budget in fiscal year 1990), has set up an organizationally separate AIDS activity. At the same time, AIDS-related efforts within the institutes are subject to an unprecedented (for NIH) degree of coordination and direction by the NIH Director's Office. The goals of this oversight are many: ensuring that information is shared and advances communicated to NIH's various publics, identifying and exploiting research opportunities, filling gaps in the research program, avoiding duplication of effort, and seeing that the overall program is adequate and balanced.

Historically, large new research programs on health problems of major public concern have usually been handled organizationally at NIH by creating a new institute or center. The committee considered and rejected the option of creating a national AIDS institute. The arguments for such an institute are that it would

-

upgrade the status and visibility, and therefore the funding, of the research area;

-

accelerate research progress by focusing research efforts in an integrated program (comprising, for example, basic, clinical, epidemiological, nursing, and behavioral research) and giving attention to such related activities as communications, training, and research resources; and

-

provide a familiar, tested management structure for setting priorities and coordinating activities, including a director and administrative staff for planning and evaluation, and strong extramural oversight through a national advisory council.

The report of the IOM Committee for a Study of the Organizational Structure of the National Institutes of Health reviewed these arguments in 1984 and concluded that the results of institute creation were mixed. That committee also cited the costs of establishing new institutes, centers, or divisions (IOM/NAS, 1984:20), in particular noting that the costs of the new administrative superstructure are not always covered by increased appropriations. In addition, the increased number of institutes adds to the problems of effective program coordination by the NIH director. (Two institutes and two centers have been created since 1984, although this increased structural complexity is partially offset by the merger of two divisions.) Another problem that can arise is that the new structure fragments the scientific effort and diminishes effective communication among key scientists in the various institutes. These potential drawbacks led the 1984 committee to suggest several criteria for assessing the need for a new institute. The new entity should, for example, increase the prospects of scientific progress in a research area, and the new organizational structure should, on balance, improve communication, management, priority setting, and accountability (IOM/NAS, 1984:22–23).

Because of the profound immune deficiency caused by HIV infection, affected individuals are vulnerable to many different diseases that often involve multiple organ systems. This committee found the arguments for program decentralization compelling in that a decentralized structure allows NIH to draw on the strengths of its various institutes. (Even if there were an AIDS institute, the scope of HIV infection and AIDS is such that the NIH Director's Office would have to have a significant planning and coordination capacity.) The involvement of multiple research areas in the various institutes will better address the complexities of AIDS, thus speeding scientific progress more effectively than might be accomplished by a single institute. Most if not all the advantages of a single-institute program–improved communication, management, priority setting, and accountability–could be achieved by implementing the committee's recommendations regarding the AIDS program management system (based in the Office of the Director), increased budgetary resources, and flexibility.

The organizational elements that have evolved in the OD for administering the multi-institute AIDS research program provide a good foundation for stronger overall planning and evaluation processes and program coordination. These elements are discussed in the sections below.

Associate Director for AIDS Research

Program coordination and direction are assigned to a high-level NIH official, the associate director for AIDS research, who advises the NIH director on all aspects of the AIDS program. Anthony S. Fauci, the current incumbent and a leading AIDS researcher, was NIH's AIDS coordinator before being appointed associate director for AIDS research when the position was created in 1988. He chairs the NIH AIDS Executive Committee and represents NIH at the meetings of the PHS Executive Task Force on AIDS. He is also executive secretary of NIH's AIDS Program Advisory Committee and director of the Office of AIDS Research.

AIDS Program Advisory Committee

APAC was established by the NIH director in 1988 to provide a formal channel for external advice on AIDS research, a function previously carried out on an ad hoc basis (e.g., the Extramural Ad Hoc Consultants to the NIH AIDS Executive Committee, which issued the report, Future Directions for AIDS Research, in November 1986; the meeting of the NIH Advisory Committee to the Director on the topic, “The Role of Biomedical Research in Combating AIDS,” in November 1987). According to its charter, APAC provides advice on all aspects of AIDS research (OAR, 1987). In particular, the committee identifies opportunities to further research on AIDS and recommends initiatives; it also advises the agency on research directions and identifies areas of research that require additional effort.

When APAC was first established, the NIH director chaired the group; it is now headed by a member of the committee “to enhance the committee 's sense of self-direction” (NIH, 1988:2). APAC originally had eight members, six of whom were authorities in the fields of molecular biology, immunology, virology, neurology, pediatrics, vaccine development, antiviral development, clinical care, animal model research, retrovirology, structural biology, or epidemiology. There were also two members of the general public. The membership now has been expanded to nine authorities in the fields listed above and four public members, appointed to overlapping four-year terms.1 There is no requirement for an authority in the behavioral or social sciences or public health (although one of the current members is a behavioral scientist). As noted in the previous section, the associate director for AIDS research serves as the committee's executive secretary, and part-time staff support is provided by the OAR.

At APACs first meeting in February 1988, NIH director James Wyngaarden stated (1988:13):

This advisory committee will play a vital role in providing advice and counsel on the difficult research and science policy issues that we face as we move towards our goal of eradicating AIDS. These meetings will serve as an effective stage from which we can review our AIDS research activities in a comprehensive fashion and examine the direction, composition, and management of our efforts.

Initially the committee was to meet for two days three times a year, issue summaries of each meeting, and prepare an annual report on its activities and recommendations during the year (Wyngaarden, 1988:14). After the first year, the meetings were reduced to two a year, and subcommittees on vaccines, therapeutics, and biosafety were established. Proceedings for each meeting have been published, but the committee has issued no annual reports. Meeting topics were as follows: introduction and overview of the NIH AIDS research program (February 1988), obstacles and opportunities in the development and testing of HIV vaccines (July 1988), development and evaluation of therapeutics for AIDS (December 1988), special considerations in the treatment of HIV infection for children and minorities (June 1989), recent developments in clinical trials, epidemiology, and central nervous system disease (December 1989), and emerging issues in drug and vaccine development and immunopathogenesis research (June 1990).

So far, APAC has provided valuable input on specific issues but has not addressed overall priorities and balance in NIH's AIDS research effort. Neither has it contributed to the preparation of annual program plans and budgets. The meetings consist largely of presentations by panels of AIDS researchers and agency officials, followed by committee discussions and, sometimes,

|

1 |

Appendix C lists the current membership of APAC. |

recommendations to the NIH director. For example, the committee at its June 1989 meeting made a series of recommendations concerning access to clinical trials, reimbursement for AIDS drugs, and coordination among NIH, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Health Care Financing Administration; the recommendations were then sent by NIH to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. At its second meeting the committee reviewed and commented on a draft of NIH's plan for AIDS vaccine development and evaluation.

NIH AIDS Executive Committee

In July 1982, NIH director James B. Wyngaarden asked his special assistant to set up an interinstitute coordination group to track AIDS activities and exchange information and to attend meetings of the PHS task force on AIDS (Gordon, 1983). When Wyngaarden discovered that NIAID and CDC, which were collaborating with French researchers to identify the AIDS virus, were unaware of similar efforts in Robert Gallo's NCI laboratory (U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, 1985:28), he established an NIH AIDS executive committee in May 1984. The committee, which Wyngaarden chaired, was composed of representatives from the institutes conducting AIDS research (NCI, NINDS [National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke], NICHD, and NIAID).

When Anthony Fauci was appointed AIDS coordinator in 1985, NIH reconstituted the NIH AIDS Executive Committee (NAEC) to include the directors of each institute involved in AIDS research or high-level alternates with the authority to make decisions on behalf of their organizations. The strengthened committee advised the NIH director on allocation of the $70 million for AIDS research that had been appropriated to the OD for fiscal year 1986; it was also given the assignment of “providing guidance and direction for NIH-wide scientific, planning, and resource allocation decision-making and for ensuring effective coordination” (Wyngaarden, 1985). NAEC was supported at first by the Office of Program Planning and Evaluation and later by the OAR, after it was established. In recent years, the AIDS coordinators rather than the directors of the various institutes have attended the meetings. The committee originally met twice a month, after the meetings of the PHS Executive Task Force on AIDS, to receive updates on developments and provide advice on NIH's contributions to PHS AIDS policy development. Usually, one of the institutes would also give a presentation on its AIDS activities. Recently, meetings were changed to a monthly basis because, according to Fauci (1990), “ [t]he original purpose of the NAEC was to serve as an in-house advisory committee to the NIH Director on matters of NIH AIDS research policy and budget. As the NIH AIDS research program has matured, with much interaction between the individual ICDs [institutes, centers, and divisions] and the Office of AIDS Research, the NAEC meetings no longer serve that purpose to the same degree.”

Office of AIDS Research

Staff work on AIDS matters initially was conducted by analysts in the OD's Office of Program Planning and Evaluation (now the Office of Science Policy and Legislation; Rodriguez, 1989). OAR was created in April 1988 to handle the workload created by AIDS budget increases of 111 percent in fiscal year 1986, 94 percent in 1987, and 81 percent in 1988, and the establishment of AIDS research programs in every institute, center, and division of NIH. OAR coordinates NIH intra-and extramural AIDS research, represents the NIH director on AIDS-related matters, and centralizes certain AIDS-related policy and operating functions, such as the development of the NIH annual budget request for AIDS and an AIDS research information system (PHS, 1989a:274).

Specifically, according to NIH's statement of organization and functions (Federal Register, April 28, 1988:15290), OAR

(1) [a]dvises the Director, NIH, and senior staff on the development of NIH-wide policy related to AIDS research, and coordinates NIH intramural and extramural AIDS research activities; (2) provides the Chairperson for the NIH AIDS Executive Committee and represents the Director, NIH, on all outside AIDS-related committees requiring NIH participation; (3) provides staff support to the NIH AIDS Executive Committee and the NIH AIDS Advisory Committee; (4) recommends intra-mural/extramural AIDS research priorities to the Director, NIH; (5) develops an NIH annual plan and budget for AIDS research; (6) develops policy on laboratory safety for AIDS researchers and monitors the AIDS surveillance program; (7) develops and maintains an information data base on intramural/extramural AIDS activities and prepares special or recurring reports as needed; (8) develops information strategies to assure that the public is informed of NIH AIDS research activities; (9) recommends solutions to ethical/legal issues arising from intramural/extramural AIDS research; (10) facilitates cooperation in AIDS research between government, industry, and universities; and (11) fosters and develops plans for NIH involvement in international AIDS research activities.

In November 1988, OAR was established legislatively through the Health Omnibus Program Extension Act (P.L. 100-607) to provide administrative support to the NIH director. It accounts for 19 of the 29 full-time equivalent (FTE) AIDS positions and $3.4 million of the $12.1 million allocated to AIDS in the OD budget for fiscal year 1990.2

OAR's day-to-day operations are supervised by deputy director Jack Whitescarver, who was appointed to the position in August 1988. The office is organized by function (e.g., program analysis, budget analysis, data management, legislative analysis; Figure 2.3). As of October 15, 1990, the office had 16 full-time employees in 19 approved positions and was requesting three more slots, for a total of 22 (Table 2.1). One of the vacant positions is that of a high-level health science administrator with AIDS research experience.

The OAR budget for fiscal years 1988–1991 is shown in Table 2.2. The OAR budget also supports the costs of the AIDS Program Advisory Committee (about $170,000 a year, including $36,000 in OAR staff support). If the President's budget request for fiscal year 1991 is funded, the OAR budget will increase $2.3 million (65 percent) to $5.7 million. More than half the increase ($1.3 million) is for AIDS programs (technology transfer meetings and loan repayments for NIH AIDS researchers) rather than for increased interinstitute program planning and coordination capacity. The increase assumes a staffing level of 22 FTEs.

Much of the work of OAR staff involves collecting and compiling information on the AIDS activities conducted by the various components of NIH for administrative and congressional reports and to satisfy numerous ad hoc requests. For example, OAR staff provided information on AIDS

|

2 |

The other FTEs (whose support totals $522,000) are located in central administrative services offices, such as the Division of Contracts and Grants and the Division of Personnel Management, where they handle some of the extra workload caused by AIDS activities. The remaining $8.1 million in OD AIDS funds support extramural AIDS activities in the Research Centers for Minority Institutions (RCMI) program of the NIGMS (all RCMI funding will be transferred to NIGMS in fiscal year 1991), intramural basic research projects on the structure and function of HIV, and a project conducted by NIH's Protein Expression Laboratory to isolate and purify proteins encoded by the HIV virus for research purposes (the last two activities are administered by the Office of Intramural Research). |

for the so-called Moyer Report on annual research accomplishments that was prepared for appropriation hearings (PHS, 1989b), the annual report on AIDS activities mandated by the Health Omnibus Program Extension Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-607), and the quarterly Institute AIDS Science Report on new research findings from intramural and extramural activities. The OAR's information compilation capacity will be greatly increased as the automated AIDS Research Information System comes on line over the next year. The staff also coordinate NIH's responses to information requests or policy development initiatives from the PHS Executive Task Force on AIDS.

The development of NIH's annual budget request for AIDS is another activity to which OAR staff contribute. This process, under the leadership of the associate director for AIDS research and the NIH director, is much more intensive than the NIH director's review of other NIH activities, which come under the purview of the individual institutes. The director's review of non-AIDS budgets focuses on aggregate numbers of projects and dollars by mechanism (e.g., how many new and competing research project grants will be funded, how many center grants will be supported); the review of the AIDS budget, however, extends to the examination of individual studies and projects at each stage of the budget process (Mahoney et al., 1990). The authority to approve budget requests gave the director and associate director for AIDS research influence over the shape and direction of AIDS research during the years when the budget was increasing quickly, even though Congress appropriated funds directly to the individual institutes and not to the director of NIH. Use of budget formulation authority to influence the AIDS research program will have less and less effect as the program matures and the rate of budget growth slows.

OAR participates in several coordination efforts among the institutes and between NIH and other agencies (OAR, 1990; PHS, 1989a:274–277). For example, OAR

-

coordinated the development of AIDSTRIALS, the centralized information system for AIDS clinical trials involving NIAID, the National Library of Medicine, and the Food and Drug Administration;

-

oversaw development of NIH's policies for the medical management of employees exposed occupationally to HIV infection, in conjunction with the NIH clinical center, the NIH Division of Safety, and CDC (subsequently, OAR was involved in the development of a PHS-wide policy published by CDC [1990]);

-

coordinates NIH responses to congressional requirements, such as the plan to double the capacity of the outpatient AIDS programs of NCI and NIAID as called for in the Health Omnibus Program Extension Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-607) and a section of the Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-381); the plan authorizes $20 million for demonstration projects to coordinate NIH clinical trials with health care delivery programs of the Health Resources and Services Administration to increase the participation of women, children, IV drug users, and other groups that are underrepresented in AIDS clinical research; and

-

participates in efforts to increase international information sharing, exchange visits, and research collaboration to increase knowledge and support the development of the infrastructure needed to conduct international clinical trials of vaccines.

Last year, OAR began to develop an NIH AIDS plan, an effort that was subsumed by the development of a PHS-level strategic plan for HIV/AIDS activities. Currently, OAR is coordinating and editing NIH 's contribution to the plan, which delineates the areas NIH and the other PHS agencies will emphasize over the next several years, including key actions and outcomes to be achieved (PHS, 1990).

STRENGTHENING MANAGEMENT OF THE NIH AIDS RESEARCH PROGRAM

As an “institute without walls,” NIH's AIDS research program is managed from the Office of the NIH Director (instead of being organized under a particular institute). The elements of the program's organizational structure are analogous to those of the various institutes: a director (the associate director for AIDS research), a national advisory council (the AIDS Program Advisory Committee), an executive committee of senior program officials (the NIH AIDS Executive Committee), and an executive office for staff support (the Office of AIDS Research). The committee believes these organizational arrangements and associated administrative processes for managing AIDS research should be strengthened as an alternative to the creation of a separate institute and institutionalized as part of a major, long-term program at NIH.

Strengthening Planning and Evaluation

Planning

AIDS program planning at NIH has been a by-product of the budget process and is based on expected resources rather than on program goals and scientific opportunities. Currently, it comprises two major events. In January each institute conducts a half-day briefing for the director and OD staff in preparation for appropriations hearings. An additional half day is devoted to a briefing on the AIDS program, which is attended by the NAEC representatives from each institute. (The January 1990 briefing, for example, covered major cross-cutting areas of research: pediatrics, vaccines, treatment, and underserved populations.) The second event is the development of an agenda and background materials for a November meeting between the NIH director and the assistant secretary for health to launch the annual budgeting process.

In contrast, the institutes each develop their own annual plan using a process that reviews goals, objectives, and research strategies; evaluates program progress; assesses scientific opportunities; sets priorities; and modifies program directions and emphases accordingly, all with the involvement of the institute's national advisory council and the scientific community (through various advisory committees and panels). In the past the AIDS program never developed a formal, detailed program plan that encompassed the above steps but instead launched initiatives as needs became apparent. Now, however, limited resources and competing demands are constraining AIDS research initiatives. Given the large size and organizational complexity of NIH AIDS research, the committee believes program management as well as program effectiveness would be improved by the development of an overall long-range research plan. The plan should set out the program's goals and assign priorities. It should define the resources required and mechanisms to be used and identify the results that are expected over specific time periods. Rather than a blueprint that specifies how investigators should proceed, the plan should be a roadmap that identifies goals but permits multiple routes. It should allow a significant amount of basic, undirected research initiated by investigators with good ideas, because historically this has been the method used to produce many important scientific advances. The plan should also be flexible to allow prompt adaptation to unanticipated events that alter prior assumptions. Accordingly, the plan should be subject to periodic review and revision through a formal decision process. The overall plan should be issued annually in light of accumulated revisions. Because some work products may be available in less than a year while some may not be available for more than five years, formal interim and endpoint reviews should be part of the plan.

Recommendation 2.1: NIH should develop a five-year plan to identify AIDS-related research needs and opportunities, set priorities, assess program balance, identify

research areas that need stimulation, determine the resources required to carry out the program, and evaluate progress. The plan should be developed under the auspices of the AIDS Program Advisory Committee (after the committee is expanded and oriented as recommended below), with the input of outside experts as well as OAR staff, and it should be reviewed and updated annually. The annual plan review should occur in time to guide the preparation of the regular annual budget so that responsibilities and resources can be shifted if appropriate.

Evaluation

Most of NIH's AIDS research activities were hurriedly launched by limited staff during the years of rapid budgetary growth. As the program matures, however, attention is appropriately turning to the relevance, effectiveness, and efficiency of ongoing activities. There are several evaluation mechanisms already in place. The associate director for AIDS research relies on NIH's time-honored method of evaluation and quality control –peer review of research applications by study sections of independent experts. The Division of Planning and Evaluation in the OD's Office of Science Policy and Administration also coordinates a formal evaluation program of “discrete, circumscribed studies and analyses of selected aspects of the NIH mission,” using a 1 percent evaluation set-aside fund ($4.5 million in fiscal year 1990; NIH, 1989:1). But AIDS research presents several unique problems. Many AIDS grants involve large, multidisciplinary projects, centers, and cooperative-group efforts that are closely related to an institute's categorical mission. Scientific review of these projects is essential but insufficient, because administratively they pose quite different questions of efficiency, effectiveness, and productivity than projects involving an individual investigator in a lab. Evaluation of an AIDS clinical trials unit, for example, involves issues of accrual rates, data-gathering accuracy and efficiency, timeliness of reporting, and protocol compliance of patients and providers–in addition to issues of scientific excellence in the research design and data analysis plan. These features of AIDS research call not only for stronger program planning but for stronger evaluation efforts and close linking of planning and evaluation results to the budget allocation process.

Recommendation 2.2: AIDS program evaluation processes should be strengthened and linked closely to planning and budgeting processes to ensure that, first, questions of the highest priority are addressed adequately at all times; second, all studies being supported are still relevant and are as productive and efficient as possible; and third, resources are redeployed, sometimes across institutes, in response to research advances and breakthroughs or as time and experience indicate that some programs are more and some less successful than others in achieving their goals. The Office of AIDS Research should work closely with the Division of Planning and Evaluation in the NIH Director's Office to coordinate evaluations of AIDS research programs in the various institutes. In turn, evaluation results should be considered in program planning and budgeting.

Strengthening External Advisory Processes

One of NIH's strengths is its ability to incorporate external advice from scientists and the public in its planning and operations. As in its other research programs, NIH has established advisory groups at every level of the AIDS research program; many of these groups include patient

advocates and members of the general public as well as scientists and researchers.3 Most of these advisory groups address specific technical aspects of the AIDS research program; because of their number and specificity, the committee could not evaluate each group's appropriateness and usefulness. The associate director for AIDS research should routinely reevaluate the need for such committees as the AIDS research program is institutionalized over the next several years as a long-term effort.

Not in question, however, is the need for a high-level advisory function, and the committee urges NIH to strengthen its processes for external advice on overall level of effort, balance among research areas and mechanisms, and research opportunities and needs in the AIDS research program. For the institutes, this role is played by the national advisory councils; for the AIDS program, this function should be the role of the AIDS Program Advisory Committee. APAC should review annual program and budget plans and oversee development of the five-year AIDS research plan recommended above with extensive external input –for example, as the National Advisory Eye Council prepares five-year national vision research plans. This responsibility would require substantially increased staff support (rather than the part-time staffing now provided by the OAR).

APACs goal should be a research program that focuses on acquiring fundamental knowledge about HIV and its transmission and pathogenesis and on developing and testing new agents and programs to prevent and treat HIV infection and AIDS. APACs guiding policy should include optimum use of all possible resources toward these ends; thus the program should take into account the contributions of other government agencies, as well as private organizations and companies.

Although recently APAC membership was increased from 8 to 13, including 4 members of the general public, the committee believes the group should be enlarged further to ensure that all areas of AIDS research and AIDS research policy and administration are adequately represented. National advisory councils to the institutes typically have 18 members, 12 with health and science expertise (including public health and the social and behavioral sciences) and 6 public members with backgrounds in public policy, law, economics, and management. APACs base of expertise could also be expanded by naming additional non-APAC members to the committee's subcommittees.

Recommendation 2.3: The AIDS Program Advisory Committee should take a larger role in providing broad policy advice and program oversight and should include among its activities the development of the five-year AIDS research plan and annual updates. It should also conduct an annual review of the programs and budgets developed to implement the plan. This expanded role will require additional staff support and a larger committee to ensure that all AIDS-related areas of expertise are represented, including the behavioral and social sciences and public health authorities. It may also require the establishment of additional subsidiary committees and the recruitment of additional outside experts to review the various research areas (e.g., basic, behavioral, epidemiological).

|

3 |

In November 1990 NIAID announced that the ACTG was adding patient and community representatives to its executive committee and each of its research committees (e.g., primary infections, pediatric AIDS, etc.). |

Strengthening Staff Support

The expanded roles of the associate director for AIDS research and the AIDS Program Advisory Committee in planning, evaluation, and budgeting will require some additional staff support by the Office of AIDS Research and related OD units-the divisions of financial management and planning and evaluation, for example. Fortunately, OAR receives excellent budgeting support from the OD's financial management division and is developing the computer-based AIDS Research Information System, which will support these expanded planning, budgeting, and program evaluation efforts.

In most areas of the AIDS research program, the associate director for AIDS research and the OAR will coordinate activities that are actually carried out by the institutes, centers, and divisions; they should play a larger role, however, in planning, implementing, and evaluating certain cross-cutting functions–for example, training and construction programs (see Chapter 4). In addition, as the committee recommends later in this report, the OAR should review and approve AIDS RFAs and RFPs initiated by the individual institutes in accordance with their priority in the overall plan for AIDS research.

As it did for other governmental units, the Office of Management and Budget established an FTE ceiling for fiscal year 1991 for the OAR, restricting its staff to the 16 positions already assigned to it. When the restriction was eased in early 1990, OAR immediately added 3 positions and requested funding for 3 more in fiscal year 1991 to accomplish its current workload. The additional work called for in this report will require additional personnel, some with high-level science training and AIDS-related research experience.

Recommendation 2.4: The capacity of the Office of AIDS Research should be increased so that it can function adequately as the staff arm of the associate director for AIDS research in his or her role as leader and coordinator of the AIDS program. In particular, OAR will need some additional planning and evaluation staff, including several senior-level scientists who can assist the associate director for AIDS research and APAC in monitoring the AIDS research agenda, assessing progress, identifying scientific gaps that need to be addressed, and coordinating the review of institute research initiatives.

Strengthening Executive Authority and Flexibility

The AIDS program is the first major research program to be managed by the Office of the NIH Director rather than by a single institute. The committee believes, therefore, that the OD's capacity to implement and coordinate AIDS research activities should be strengthened, in addition to the enhancement of its long-range planning and evaluation capabilities, as recommended above.

Past evaluations of the structure and performance of NIH have noted the loss of influence of the NIH director within the Department of Health and Human Services and the Office of Management and Budget on the one hand, and the individual institutes on the other (White House, 1965; U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare [U.S. DHEW], 1976; IOM/NAS, 1984, 1988; Singer, 1990). These evaluations concluded that, although decentralized authority is good for a basic research organization, the NIH director needs clear authority and specifically allocated resources to ensure a coordinated response to scientific opportunities or public health emergencies. For example, once Congress approves the NIH budget, the director has power only over the OD budget, which is 1.4 percent of the overall agency appropriation; the rest of the funds are

appropriated directly to each institute, center, and division, and the director does not now have authority to reallocate them in response to contingencies that may emerge during the fiscal year. Review groups have regularly recommended several steps to strengthen the director 's position within the agency.

-

The NIH director should have greater discretion over resource allocation to allow flexible responses to health emergencies (such as the AIDS epidemic) and exploitation of emerging scientific opportunities.

-

Advisory groups to the director should be strengthened to identify problems facing NIH and help build political consensus for solutions.

-

The director should have a discretionary fund “for correcting imbalances, for exploiting new scientific opportunities, and for contingencies” (U.S. DHEW, 1976:16) or “to be used to address emerging issues and special inter-institute research opportunities” (IOM/NAS, 1988:138).

-

The director should have authority to transfer funds (up to 0.5 or 1 percent) across institute lines to meet contingencies (White House, 1965:16; IOM/NAS, 1984:32; Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic, 1988:41; Singer, 1990).

The recent report of the IOM Committee to Study Strategies to Strengthen the Scientific Excellence of the NIH Intramural Research Program recommended that Congress appropriate no less than $25 million annually to be used by the NIH director to address emerging issues and special interinstitute research opportunities (IOM/NAS, 1988:138). The administration 's budget request for fiscal 1991 included $20 million for an NIH director's discretionary fund, “an important mechanism that would allow the NIH to respond more effectively to unforeseen changes in research direction and emerging research opportunities” (PHS, 1989a:Vol. 6, p. 263) and authority to transfer up to 1 percent of NIH appropriations “to high priority activities the Director may so designate” (U.S. PHS, 1989a:Vol. 6, p. 252). Congress recently approved the 1 percent transfer authority and $20 million “as a director's reserve for high priority needs of the NIH” (U.S. Congress, 1990:21), but it is not clear that it is a revolving fund that will be automatically replenished each year.

Recommendation 2.5: The director of NIH should be given an adequate annually renewed discretionary fund of at least $20 million along with additional authority to transfer up to 1 percent of each NIH appropriation account to increase the agency's flexibility in responding to future emergencies or research opportunities. These resources could be used to exploit important scientific breakthroughs arising in AIDS or non-AIDS research that could not be anticipated in the regular budget process or to address major epidemics or other public health problems that suddenly emerge.

The committee is convinced that an important component of the current strength and success of the NIH AIDS research program is the unique leadership provided by Anthony Fauci, associate director of NIH for AIDS research and director of NIAID. Having the same person as director of NIAID, which receives nearly half the NIH AIDS budget, and associate director for AIDS research is administratively unorthodox, because it poses potential conflict of interest problems when questions of interinstitute coordination, budget allocation, and assignment of program jurisdiction arise. Each of the positions is also extremely demanding, an aspect that, in the case of the position of associate director for AIDS research, will only intensify if AIDS program management is strengthened and institutionalized, as recommended in this report. In this instance the arrangement has worked well because of the energy, knowledge, even-handedness, and prestige of the incumbent.

Recommendation 2.6: The current arrangement of the same person holding the positions of both associate director for AIDS research and director of NIAID is working

TABLE 2.1 Office of AIDS Research Staff Slots

|

Fiscal Year 1989 |

Fiscal Year 1990 |

||

|

Position or Unit |

Filled |

Vacant |

Projected |

|

Deputy director |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Loan repayment |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Legislative analysis |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Budget analysis |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Medical officer |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Program analysis |

4 |

1 |

5 |

|

Data management |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|

Administration |

5 |

2 |

7 |

|

Total |

16 |

6 |

22 |

|

SOURCE: Administrative Officer, Office of AIDS Research, October19, 1990. |

|||

TABLE 2.2 Budget (in thousands of dollars) of the Office of AIDS Research (OAR), Fiscal Years 1988–1991

|

Activity |

1988 |

1989 |

1990a |

1991b |

|

Administrative services |

||||

|

Office of AIDS Research |

454.7 |

1,069.0 |

1,353.0 |

1,841.0 |

|

Office of Science Policy Legislationc |

–d |

62.0 |

77.0 |

55.0 |

|

Division of Financial Managementc |

– |

23.0 |

55.0 |

58.0 |

|

Subtotal |

454.7 |

1,154.0 |

1,485.0 |

1,954.0 |

|

OAR programs |

||||

|

Loan repayment |

– |

– |

989.0 |

2,000.0 |

|

AIDS Research Information System |

– |

– |

500.0 |

1,000.0 |

|

Technology Transfer Regional Meetings |

– |

– |

480.0 |

750.0 |

|

Subtotal |

– |

– |

1,969.0 |

3,704.0 |

|

Total |

454.7 |

1,154.0 |

3,454.0 |

5,704.0 |

|

aEstimated. bPresident's budget. cThe persons assigned to AIDS research in legislative analysis (Office of Science Policy Legislation) and financial analysis (Division of Financial Management) sit in those offices but work for and are paid by OAR. dDashes indicate no funds allocated. SOURCE: Administrative Officer, Office of AIDS Research, October12, 1990. |

||||

REFERENCES

CDC (Centers for Disease Control). 1990. Public Health Service statement on management of occupational exposure to human immunodeficiency virus, including considerations regarding zidovudine postexposure use. Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 39(RR-1):1–14.

Fauci, A. S. 1990. Change in scheduling of NAEC meetings. Memorandum to members, alternates, and staff of the NIH AIDS Executive Committee, September 17. Office of AIDS Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

Gordon, R. S. 1983. Interview with Robert S. Gordon, M.D., Special Assistant to the NIH Director, August 16, 1983, by Stephen B. Nelson, staff of the IOM Committee for a Study of the Organizational Structure of the National Institutes of Health.

IOM/NAS (Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Sciences). 1984. Responding to Health Needs and Scientific Opportunities: The Organizational Structure of the National Institutes of Health. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

IOM/NAS. 1988. A Healthy NIH Intramural Program: Structural Change or Administrative Remedies? Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Mahoney, J. D., R. Miller, and D. Adderly. 1990. Interview with John D. Mahoney, Associate Director for Administration; Richard Miller, Assistant Budget Director; and Donna Adderly, Budget Analyst, NIH, March 22, 1990, by Michael McGeary, Study Director, and Robert Walkington, Consultant, IOM Committee.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 1988. The Development and Evaluation of Therapeutics for AIDS. Proceedings of the Third Meeting of the AIDS Program Advisory Committee, December 5-6. Bethesda, Md.: Office of AIDS Research, National Institutes of Health.

NIH. 1989. National Institutes of Health Evaluation Plan, FY 1990. Bethesda, Md.: Office of Science Policy and Legislation, National Institutes of Health.

OAR (Office of AIDS Research). 1987. Charter, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Program Advisory Committee, NIH, approved by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, September 24, 1987.

OAR. 1990. Major program initiatives. October 3. Office of AIDS Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

PHS (Public Health Service). 1989a. Justification of Appropriation Estimates for Committee on Appropriations, Fiscal Year 1991. Vol. 6, National Institutes of Health, Research Resources through Office of the Director. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

PHS. 1989b. Justification of Appropriation Estimates for Committee on Appropriations, Fiscal Year 1991. Vol. 9, Public Health Service Supplementary Budget Data (Moyer Material), Part 1. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

PHS. 1990. The Role of the Public Health Service in Combatting the HIV/AIDS Epidemic (August 31 draft). Washington, D.C.: National AIDS Program Office.

Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic . 1988. Report of the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic. June 24. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Rodriguez, D. 1989. Interview with Dennis Rodriguez, Program Analyst, Office of AIDS Research, August 21, 1989, by Michael McGeary, Study Director, and Robert Walkington, Consultant, IOM Committee to Study the AIDS Research Program of the NIH.

Singer, M. 1990. NIH Director Recommendations (letter to the editor). Science 248:795.

U.S. Congress. 1990. Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 5257, Making Appropriations for the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies, for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1991, and for Other Purposes, Appropriation Bill, 1990. House Report 101-908. 101st Cong., 2nd sess. October 20.

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. 1985. Review of the Public Health Service's Response to AIDS. Technical Memorandum, OTA-TM-H-24. February. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. DHEW (U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare). 1976. Report of the President's Biomedical Research Panel. DHEW Publication No. (OS) 76-500. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

White House. 1965. Biomedical Science and Its Administration: A Study of the National Institutes of Health. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Wyngaarden, J. B. 1985. NIH Coordination of AIDS Research. Memorandum from the Director, NIH, to Directors of Bureaus, Institutes, and Divisions and Office of the Director Staff, October 15. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

Wyngaarden, J. B. 1988. Mission and role of the AIDS Program Advisory Committee. In Annotated Agenda, 1st Meeting of the AIDS Program Advisory Committee, February 26. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.