THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, NW Washington, DC 20001

NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance.

This study was supported by Contract VA241-P-2024 between the National Academy of Sciences and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the organizations or agencies that provided support for this project.

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-26764-9

International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-26764-1

Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, NW, Keck 360, Washington, DC 20001; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313; http://www.nap.edu.

For more information about the Institute of Medicine, visit the home page at: www.iom.edu.

Copyright 2014 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

The serpent has been a symbol of long life, healing, and knowledge among almost all cultures and religions since the beginning of recorded history. The serpent adopted as a logotype by the Institute of Medicine is a relief carving from ancient Greece, now held by the Staatliche Museen in Berlin.

Suggested citation: IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2014. Gulf War and health, volume 9: Long-term effects of blast exposures. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES

Advisers to the Nation on Science, Engineering, and Medicine

The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society of distinguished scholars engaged in scientific and engineering research, dedicated to the furtherance of science and technology and to their use for the general welfare. Upon the authority of the charter granted to it by the Congress in 1863, the Academy has a mandate that requires it to advise the federal government on scientific and technical matters. Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone is president of the National Academy of Sciences.

The National Academy of Engineering was established in 1964, under the charter of the National Academy of Sciences, as a parallel organization of outstanding engineers. It is autonomous in its administration and in the selection of its members, sharing with the National Academy of Sciences the responsibility for advising the federal government. The National Academy of Engineering also sponsors engineering programs aimed at meeting national needs, encourages education and research, and recognizes the superior achievements of engineers. Dr. C. D. Mote, Jr., is president of the National Academy of Engineering.

The Institute of Medicine was established in 1970 by the National Academy of Sciences to secure the services of eminent members of appropriate professions in the examination of policy matters pertaining to the health of the public. The Institute acts under the responsibility given to the National Academy of Sciences by its congressional charter to be an adviser to the federal government and, upon its own initiative, to identify issues of medical care, research, and education. Dr. Harvey V. Fineberg is president of the Institute of Medicine.

The National Research Council was organized by the National Academy of Sciences in 1916 to associate the broad community of science and technology with the Academy’s purposes of furthering knowledge and advising the federal government. Functioning in accordance with general policies determined by the Academy, the Council has become the principal operating agency of both the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Engineering in providing services to the government, the public, and the scientific and engineering communities. The Council is administered jointly by both Academies and the Institute of Medicine. Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone and Dr. C. D. Mote, Jr., are chair and vice chair, respectively, of the National Research Council.

COMMITTEE ON GULF WAR AND HEALTH:

LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF BLAST EXPOSURES

STEPHEN L. HAUSER (Chair), Chair, Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco

JEFFREY J. BAZARIAN, Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, NY

IBOLJA CERNAK, Chair, Canadian Military and Veterans’ Clinical Rehabilitation Medicine, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

LIN CHANG, Professor, Division of Digestive Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine

KIMBERLY COCKERHAM, Zeiter Eye Medical Group, Inc., Stockton, CA, and Adjunct Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, Stanford University School of Medicine, CA

KAREN J. CRUICKSHANKS, Professor, Departments of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences and Population Health Sciences, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison

FRANCESCA DOMINICI, Professor, Department of Biostatistics, Harvard University School of Public Health, Boston, MA

JUDY R. DUBNO, Professor, Department of Otolaryngology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston

THEODORE J. IWASHYNA, Associate Professor, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor

S. CLAIBORNE JOHNSTON, Professor, Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco

S. ANDREW JOSEPHSON, Associate Professor, Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco

KENNETH W. KIZER, Distinguished Professor, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine and Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing, Sacramento, CA

WILLIAM C. MANN, Distinguished Professor and Chair, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Florida, Gainesville

LINDA J. NOBLE-HAEUSSLEIN, Professor, Departments of Neurological Surgery and Physical Therapy, University of California, San Francisco

EDMOND L. PAQUETTE, Dominion Urological Consultants and Assistant Professor, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Fairfax

ALAN L. PETERSON, Professor and Chief, Division of Behavioral Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio

KAROL E. WATSON, Associate Professor, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine

IOM Staff

ABIGAIL MITCHELL, Study Director

CAROLYN FULCO, Scholar

HEATHER COLVIN, Program Officer (until July 2012)

EMILY MORDEN, Research Associate (until May 2013)

JONATHAN SCHMELZER, Research Assistant

JOSEPH GOODMAN, Senior Program Assistant

DORIS ROMERO, Financial Associate

NORMAN GROSSBLATT, Senior Editor

FREDERICK ERDTMANN, Director, Board on the Health of Select Populations

Consultant

MIRIAM DAVIS, Independent Consultant

Reviewers

This report has been reviewed in draft form by persons chosen for their diverse perspectives and technical expertise in accordance with procedures approved by the National Research Council’s Report Review Committee. The purpose of this independent review is to provide candid and critical comments that will assist the institution in making its published report as sound as possible and to ensure that the report meets institutional standards of objectivity, evidence, and responsiveness to the study charge. The review comments and draft manuscript remain confidential to protect the integrity of the deliberative process. We thank the following for their review of the report:

John F. Ahearne, Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society

Stephen V. Cantrill, Denver Health Medical Center

Ralph G. Dacey, Washington University School of Medicine

Jordan Grafman, Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago

John B. Holcomb, US Army Institute for Surgical Research

Mark S. Humayun, University of Southern California School of Medicine

Thomas E. Kottke, HealthPartners

Cato T. Laurencin, University of Connecticut

Henry Lew, University of Hawaii at Manoa

Roger O. McClellan, Independent Advisor on Toxicology and Human Health Risk

Robert F. Miller, Vanderbilt Medical Center

Eric J. Nestler, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

Andrew C. Peterson, Duke University Medical Center

Rosemary Polomano, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

Myrna M. Weissman, Columbia University

Although the reviewers listed above have provided many constructive comments and suggestions, they were not asked to endorse the conclusions or recommendations, nor did they see the final draft of the report before its release. The review of the report was overseen by Michael I. Posner, University of Oregon, and David G. Hoel, Medical University of South Carolina. Appointed by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine, respectively, they were responsible for making certain that an independent examination of the report was carried out in accordance with institutional procedures and that all review comments were carefully considered. Responsibility for the final content of the report rests entirely with the authoring committee and the institution.

Preface

Since the United States began combat operations in Afghanistan in October 2001 and then in Iraq in March 2003, the numbers of US soldiers killed exceed 6,700 and of US soldiers wounded, 50,500.1 Although all wars since World War I have involved the use of explosives by the enemy, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq differ from previous wars in which the United States has been involved because of the enemy’s use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The use of IEDs has led to an injury landscape different from that in prior US wars. The signature injury of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars is blast injury. Numerous US soldiers have returned home with devastating blast injuries, and they continue to experience many challenges in readjusting to civilian life.

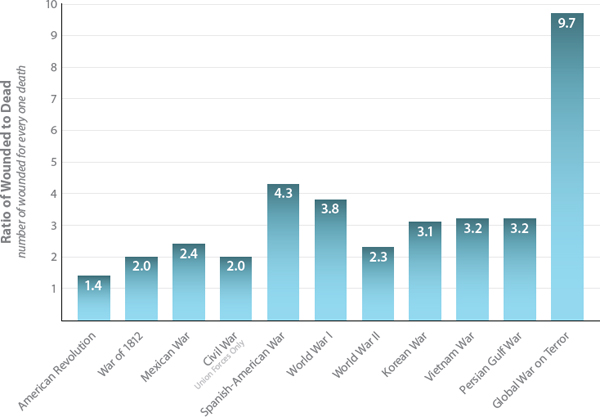

Throughout history, theaters of war have created a stimulus for medical innovation—in technology, emergency care, surgery, and therapeutics—and especially during the past half-century the resulting advances in battlefield medicine have dramatically improved outcomes for wounded warriors (see Figure P-1). However, in the case of blast-related injuries in particular, knowledge of clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, means of prevention, and best therapies has lagged behind the understanding of those related to other combat-related traumas. In the late 18th century, Pierre Jars first proposed that changes in air pressure resulting from explosion, “la

_________________

1DOD (Department of Defense). 2013. US Department of Defense Casualty Status. www.defense.gov/news/casualty.pdf (accessed September 1, 2013).

FIGURE P-1 In contrast with earlier wars, the recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq have witnessed a dramatic increase in the ratio of wounded to deceased soldiers, owing in large part to improvements in battlefield medicine.

SOURCE: Data provided by DOD (Department of Defense). 2013a. U.S. Military Casualties: GWOT Casualty Summary by Service Component. https://www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/report_sum_comp.xhtml (accessed September 5, 2013); and DOD. 2013b. Principal Wars in which the United States Participated: U.S. Military Personnel Serving and Casualties. https://www.dmdc.osd.mil/dcas/pages/report_principal_wars.xhtml (accessed September 5, 2013).

grande et prompte dilation d’air,” could produce bodily injury or death.2 That early insight notwithstanding, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, blast-related injuries were more often attributed, incorrectly, to poisoning from gases released in the explosions rather than to pressure waves.3

The modern understanding of blast injury dates from observations on the widespread use of explosives in World War I. Rusca (1915) and Mott (1916) reported that blast explosions could produce fatal injuries without

_________________

2Hill, J. F. 1979. Blast injury with particular reference to recent terrorist bombing incidents. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 61(1):4-11.

3Born, C. T. 2005. Blast trauma: The fourth weapon of mass destruction. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 94(4):279-285.

any external signs of trauma,4,5 Hooker (1924) first described the pathophysiology of blast lung,6 the high risk of hearing loss due to ear trauma was recognized at about the same time, and shell shock became familiar as a term to describe the neurologic and emotional sequelae of blast exposure. The aerial bombing campaigns of World War II and our later entry into the nuclear age stimulated a renewed focus on the many adverse health consequences, acute and chronic, blast injury can have.7 In recent years, priorities have been shaped by the devastating consequences of IEDs deployed in terrorist attacks against civilians and targeted against military personnel in the current wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The committee had two tasks. The first task was to evaluate what is known about health effects of exposure to blast, including the blast waves (the supersonic waves of intense air pressure that follow detonation of an explosive device) and other blast mechanisms, such as blunt-force trauma from projectiles, and to draw conclusions about the strength of the evidence. The committee used an evidence-based approach to identify and evaluate the relevant scientific and medical information on health effects of exposure to blast. Not much information was available in that regard. In particular, research efforts often do not separate blast injuries caused by blast waves from those caused by blunt-force trauma and other mechanisms. Although the committee recognizes that blast injuries are often caused by more than one mechanism and do not occur in isolation and that blast injury typically elicits a secondary multisystem response, it will be important to gain a better understanding of how different blast mechanisms and exposure to repeated blasts directly affect the body. Acute injuries from blast may not be apparent immediately after exposure, especially when people are exposed to the blast waves but not to blunt-force trauma. For example, blast waves alone can affect the nervous system without leaving an obvious acute injury, and blast-related symptoms, such as persistent headache, can develop much later.

The committee’s ability to draw conclusions about associations between exposure to blast and health effects, particularly long-term health effects, was severely restricted by the paucity of high-quality information. The second part of its task, therefore, was to develop a research agenda to provide the Department of Veterans Affairs with guidance in addressing the

_________________

4Rusca, F. 1915. Historical article first describing primary blast injury. Deutcsche Zeitschrift f. Chirurgie 132:315.

5Mott, F. W. 1916. Special discussion on shellshock without visible signs of injury. Proceedings Royal Society Medicine 9:i-xxiv.

6Hooker, D. R. 1924. Physiological effects of air concussion. American Journal of Physiology 67(2):219-274.

7Bellamy, R. F., and J. T. Zajtchuk. 1998. Conventional Warfare. Ballistic, Blast, and Burn Injuries. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General (Army).

deficiencies in the evidence base. The committee hopes that this research will lead not only to a better understanding of the long-term health effects of exposure to blast but also to improved protective measures for soldiers in the future and to improved treatments for soldiers who experience blast injuries.

The committee is honored to dedicate its report to the men and women who are bravely serving in Middle East battlegrounds, to those who have returned home safely, to our fellow citizens who are recovering from the wounds of war, and to the memory of those who have made the ultimate sacrifice on our behalf. Words cannot convey the depth of our gratitude.

The committee thanks everyone who presented during its public meetings and who provided information that helped us to develop our approach to and thinking about the statement of task. In particular, the committee is grateful to the following: Christopher Crnich, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health; Dallas Hack, Combat Casualty Care Research Program, US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command; Mary Lawrence, The Vision Center of Excellence, Department of Defense and Department of Veterans Affairs; Michael Leggieri, Department of Defense Blast Injury Research Program Coordinating Office, US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command; Geoffrey Ling, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency; Paul Pasquina, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center; Terry Walters, Veterans Health Administration; and Janet Ward, Marina Caroni, and Michael Maffeo, US Army Natick Soldier Research, Development, and Engineering Center.

Finally, the committee thanks the Institute of Medicine staff—Heather Colvin, Carolyn Fulco, Joseph Goodman, Cary Haver, Marc Meisnere, Emily Morden, and Jonathan Schmelzer—who assisted in this effort. In particular, we thank the study director, Abigail Mitchell, who guided the entire process with thoroughness, knowledge, research expertise, and a steady hand at every step along the path.

Stephen L. Hauser, Chair

Committee on Gulf War and Health:

Long-Term Effects of Blast Exposures

3 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF BLAST INJURY AND OVERVIEW OF EXPERIMENTAL DATA

Acute Blast–Body and Blast–Brain Interactions

Modifying Potential of Systemic Changes Caused by Blast

Requirements for Models of Blast-Induced Injury

Experimental Models of Multiorgan Responses to Blast

Psychologic and Psychiatric Outcomes

Auditory and Vestibular Outcomes

Musculoskeletal and Rehabilitation Outcomes

| AbdP | abdominal pressure |

| ANS | autonomous nervous system |

| AOC | alteration of consciousness |

| AOR | adjusted odds ratio |

| AUDIT | Alchohol Use Disorders Identification Test |

| BAMC | Brooke Army Medical Center |

| BINT | blast-induced neurotrauma |

| BLI | blast lung injury |

| CAP | compound action potential |

| CDH | chronic daily headache |

| CDP | computerized dynamic posturography |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CPG | clinical practice guideline |

| CTE | chronic traumatic encephalopathy |

| CVP | central venous pressure |

| DOD | Department of Defense |

| DTI | diffusion tensor imaging |

| ED | erectile dysfunction |

| EP | endocochlear potential |

| fMRI | functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| FSH | follicle-stimulating hormone |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| GHD | growth hormone deficiency |

| GU | genitourinary |

| HO | heterotopic ossification |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| IED | improvised explosive device |

| IOM | Institute of Medicine |

| ISS | injury severity scale |

| JTTR | Joint Theater Trauma Registry |

| LH | luteinizing hormone |

| LOC | loss of consciousness |

| LUTS | lower urinary tract symptoms |

| MDR | multidrug resistance |

| MPO | myeloperoxidase |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| mRNA | messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NACA | N-acetylcysteine amide |

| NAS | National Academy of Sciences |

| NNMC | National Naval Medical Center |

| OEF | Operation Enduring Freedom |

| OIF | Operation Iraqi Freedom |

| OND | Operation New Dawn |

| OPTIC | Optometry Polytrauma Inpatient Clinic |

| OR | odds ratio |

| PBI | primary blast injury |

| PFT | pulmonary function test |

| PICS | post-intensive-care syndrome |

| PL | Public Law |

| PNS | VA polytrauma network site |

| PRC | VA polytrauma rehabilitation center |

| PTA | posttraumatic amnesia |

| PTN | pentaerythritol tetranitrate |

| PTSD | posttraumatic stress disorder |

| RR | relative risk |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SimLEARN | VA Simulation Learning, Education and Research Network |

| SM-MHC | smooth muscle myosin heavy chain |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| ThorP | thoracic pressure |

| TM | tympanic membrane |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USAISR | US Army Institute of Surgical Research |

| VA | Department of Veterans Affairs |

| VHA | Veterans Health Administration |

| VSMC | vascular smooth muscle cell |

| WRAMC | Walter Reed Army Medical Center |