Overview of the Institute of Medicine Report (October 2011)

Barbara Vickrey, Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Neurology, University of California, Los Angeles, began by reiterating two questions that were central to the goals of the workshop: How can the evidence base be strengthened, and how can this process take place in a way that is targeted to what will be most helpful to the health services decision makers? Vickrey went on to summarize the charge to the committee, and its process, findings, and recommendations.

The study took place over 12 months, included two public meetings and four closed meetings, and centered on an extensive literature review. The committee’s report, released in October 2011, is divided into two sections: background and assessment of the evidence. The background section investigated definitions and types of traumatic brain injury (TBI), the factors that affect recovery, the definition of cognitive rehabilitation therapy (CRT), an evaluation of the range of interventions that fall under this umbrella, and the state of the practice of CRT.

Vickrey described the committee’s efforts to survey the various definitions of CRT as used by professional societies and health care organizations, citing one definition used by the Brain Injury Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group (BI-ISIG):

Cognitive rehabilitation is a systematic, functionally oriented service of therapeutic cognitive activities, based on an assessment and understanding of the person’s brain-behavior deficits. Services are directed to achieve functional changes by (1) reinforcing, strengthening, or reestablishing previously learned patterns of behavior; or (2) establishing new patterns of

cognitive activity or compensatory mechanisms for impaired neurological systems. (Harley et al., 1992)

The committee focused its work around the following question: Do cognitive rehabilitation interventions improve function and reduce cognitive deficits in adults with mild or moderate-severe TBI? The committee was charged with investigating the literature on interventions addressing each major cognitive domain—attention, executive function, language and social communication, visuospatial perception, and memory—as well as multi-modal interventions (CRT that comprehensively targets more than one domain). Within each cognitive domain, the committee looked for research on two severities of injury (mild TBI and moderate-severe TBI) and three stages of recovery (acute, subacute, and chronic). Regarding outcomes, the committee assessed the evidence for immediate benefit and long-term benefit, and investigated whether patient-centered outcomes were assessed—whether studies examined the effects of an intervention on a patient’s reintegration into the community or demonstrated improvement in patients’ quality of life. The committee also looked for any evidence to suggest that CRT interventions are associated with risk or harm, and the committee examined the safety and efficacy of interventions delivered through “telehealth” technology.

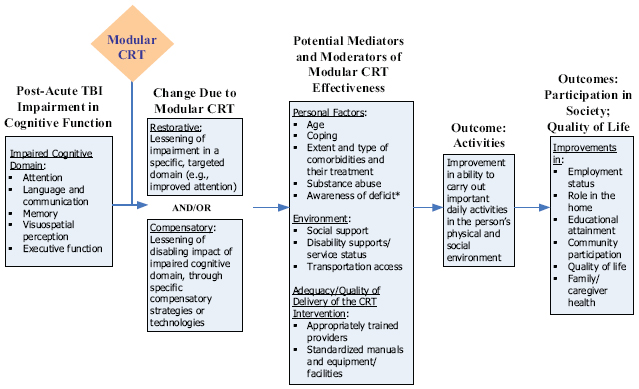

Vickrey presented a model (Figure 2-1) showing the relationship between CRT and the domains affected in a given patient on the one hand, and the desired type of change, outcome in terms of activities, and outcome in terms of broader participation in society on the other.

She highlighted the distinction between restorative and compensatory types of changes, noting that the committee treated these separately in its analysis of the literature. She also highlighted the vast heterogeneity among patients that comes into play during and after an intervention, which strongly influences the delivery of the intervention as well as the outcomes. In particular, comorbidities are very diverse among people suffering from TBI (for example, patients may also have posttraumatic stress disorder, have suffered other nonbrain injuries, or struggle with substance abuse), as are the environments in which patients live. These variables have a strong impact on the effects and success of a CRT intervention.

The committee developed a search strategy and applied it to a large number of databases, initially looking at the prior 20 years and then going back selectively to some earlier dates. The initial search yielded 856 published articles. The committee then narrowed the results according to a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and included randomized trials

FIGURE 2-1 Model for modular CRT intervening between postacute TBI cognitive impairment in a domain, and outcomes.

* For some domains, the CRT intervention may also target deficit awareness, for example, videotape of a social interaction followed by a critique will increase awareness of deficit in language and communication.

(weighted the most heavily), some pre/post studies, nonrandomized comparison groups, and experimental designs based on single subjects with controls, for certain domains. The number of studies in the narrowed group was 90.

Each study was reviewed by at least two committee members, who abstracted the key data and applied the committee’s agreed-upon grading system to judge the strength of the evidence for a particular intervention for a particular domain and for patients in a particular stage of recovery from a particular severity of brain injury. Evidence was graded according to four categories: none, limited, modest, and strong (Box 2-1). No evidence (0) meant either that no studies were found or that studies existed but were seriously flawed or otherwise very limited. Limited evidence (+) meant that the committee identified either some kind of result from one study or mixed results from two or more studies. Modest evidence (++) signified at least two studies reporting interpretable, informative, and concordant types of results. Strong evidence (+++) signified studies with high-quality study design—reproducible, consistent, large, and having good statistical power.

BOX 2-1 System for Grading the Strength of the Evidence

None or not informative (0)

No evidence because the intervention has not been studied or uninformative evidence because of null results from flawed or otherwise limited studies

Limited (+)

Interpretable result from a single study or mixed results from two or more studies

Modest (++)

Two or more studies reporting interpretable, informative, and largely similar result(s)

Strong (+++)

Reproducible, consistent, and decisive findings from two or more independent studies characterized by the following:

- Replication, reflected by the number of studies in the same direction (at least two studies)

- Statistical power and scope of studies (N size of the study and whether it is single-site or multisite)

- Quality of the study design, meaning its ability to measure appropriate endpoints (to evaluate efficacy and safety) and minimize bias and confounding

The committee prepared narrative and tabular summaries of the evidence on which its deliberations were then based.

EXAMPLE OF THE COMMITTEE’S PROCESS

Vickrey gave a snapshot of the committee’s process of assessing the evidence for CRT interventions in one domain, language and social communication. The committee found a total of five studies, of which four were randomized trials (thus given relatively greater weight) and one was a nonrandomized parallel group study. Regarding severity of injury, they found only studies of moderate-severe TBI; no information was found on interventions treating mild injuries. Regarding stage of recovery, the committee found studies only pertaining to the chronic phase. The committee graded the evidence for each study regarding immediate or long-term outcomes and regarding patient-centered outcomes, that is, improved social communication, integration into the community or social functioning in the community, or quality of life more globally.

The committee found a range of levels of evidence of the effectiveness and efficacy of CRT interventions for the various domains. For the domain of language and social communication, they found the evidence for efficacy of CRT interventions regarding patient-centered outcomes to be not informative—no studies investigated this. The committee found the evidence for short-term benefits to be modest for chronic, moderate-severe TBI, based on four randomized clinical trials and one nonrandomized trial.

The evidence for long-term benefits was found to be limited for people with chronic, moderate-severe TBI (two randomized clinical trials). Concerning the area where the evidence was modest—that of short-term benefits for chronic, moderate-severe TBI—the efficacious interventions tended to be across small-group outpatient programs employing a standardized protocol for social communication skills training. Appropriate candidates were people who had demonstrated deficits and sufficient capacity to participate in a group program.

Vickrey highlighted an important gap in the process of bringing research results to bear on clinical practice—the lack of dissemination of the studies’ details and findings. Where are those protocols posted? Where are the manuals? Where are the description and the tools that a practitioner would need if he or she wanted to deliver that intervention? Vickrey noted that some researchers post them while others do not. She described a need for the protocols and manuals to be made publicly available in order to allow others to deliver a given intervention in a larger population, either as a delivered intervention in treatment programs or for further study.

For some domains there was literature on both mild and moderate-severe TBI, while in others the literature focused on moderate-severe TBI.

Likewise, for some domains there existed studies of both subacute and chronic stages of recovery, while for others there were studies only of the chronic phase. Overall, the committee’s review showed that often where there was evidence of benefit, it was in the immediate treatment effect. Fewer studies looked at long-term effects or at patient-centered outcomes.

Regarding study design, Vickrey cited a type of study the committee encountered in which two CRT interventions were compared, but neither was standard of care and neither had been assessed independently to determine its efficacy. The committee had to set the studies aside because they lacked the appropriate comparisons that would have allowed conclusions to be drawn about the effectiveness of the interventions.

OVERALL FINDINGS FROM THE ANALYSIS OF THE LITERATURE

Vickrey explained that the literature signals evidence of some benefit of certain forms of CRT for TBI, evidence that varies across cognitive domains. The evidence is insufficient overall to provide definitive guidance for translation into clinical practice guidelines, particularly in selecting the most effective treatment(s) for a particular patient. The committee found very little evidence of adverse effects or harm associated with CRT, but it recommended that future studies assess such risks. And, the overall evidence is insufficient to clearly establish whether telehealth technology delivery modes are more or less effective or more or less safe than other means of delivering CRT.

THE LIMITATIONS OF THE CURRENT LITERATURE ON CRT FOR TBI

Vickrey discussed how the limitations of the extant body of research centered on two areas: the lack of sufficient standardization and comparability, and the lack of sufficiently powered trials. Regarding standardization, there is a need for studies to take into account the heterogeneity of patient demographics, “active ingredients” of CRT interventions, and outcome measures. In particular, she emphasized the importance of precisely describing the hypothesized active ingredients. Regarding statistical power, she noted that many studies were at the pilot stage and were not followed up with more powerful study designs that would advance the knowledge gained about a specific intervention and move it toward clinical usefulness. Even the most promising treatments lacked sufficiently powered trials to answer practical questions about (1) the relationships between patient characteristics and responses to certain treatments, (2) the lasting benefits of treatments that have positive results in the short term, and (3) how or whether treatments affect patients’ real-world tasks, community integration,

and quality of life. Subsequent studies to delve into these variables do not exist. She noted also a serious need for a plan to follow through on signals detected in early studies.

Vickrey emphasized that the committee’s conclusion that the evidence was limited signified only that the amount of evidence was limited. The type of evidence of the effectiveness of CRT for TBI was often tilted in its favor. There were definitely signals of benefit, but there was not enough information to confidently declare a generalizable benefit for any specific intervention.

The committee supported the ongoing application of CRT for TBI. Crucially, it recommended building on the literature base and considering how to design studies that build on the existing signal and strengthen the evidence to the point that it becomes useful for health services decision makers.