The Translational Pipeline and Classification Schemes for CRT Interventions

John Whyte, Director of Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute, discussed his view of clinical research as a developmental process, how the translational pipeline referred to throughout medicine applies to cognitive rehabilitation therapy (CRT) for traumatic brain injury (TBI), and where and why the translational pipeline often gets bogged down. He characterized the translational pipeline as a maturational process, one in which early studies identify a signal and are built upon by later studies that increasingly solidify the evidence and that make the use of cognitive rehabilitation therapies more practical and ultimately cost-effective. Regarding the committee’s scoring methodology, he reiterated that the scores of one plus (+) and two plusses (++) signaled not always a weak effect, but the fact that research on the interventions was at an early point in a maturational process.

The Traditional, Pharmaceutical Model of Translation

Whyte defined translational research as translating the findings of basic research into medical practice and thus meaningful health outcomes, and he began by outlining the pharmaceutical model of translation and its progression through several phases of research, noting the ways that behavioral therapy is similar or different. He described how pharmaceutically based translational research follows a relatively rigid series of steps that have different sample sizes and different typical research designs, and that are designed to answer different research problems as the maturational process

proceeds. He began with an implicit Phase 0 of idea generation, based, for example, on results from an animal model or designer drug. Phase I involves research on safety and identifying doses, generally in a small number of subjects. Phase II is proof of principle, usually a single-site clinical trial with or without a control group, depending on the natural history of the condition being studied. Phase III looks at efficacy and commonly takes the form of a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Phase IV investigates effectiveness of the drug using postmarketing surveillance.

This model serves drug development well, for example, by delaying costly research in large numbers of humans until basic safety and efficacy have been established. In contrast, Whyte noted the ways in which research on CRT is less linear and more complex. First, idea generation originates from a wide range of areas, for example, basic neuroscience, different patient populations, and engineering and studies of compensatory strategies and devices. Second, regarding safety and dose finding, dose-related toxicity is less of a factor than for drug trials; instead, the question of doses is one of impact. This means that studies often examine efficacy earlier in the maturational process than is typical with drug studies. Third, researchers must carry out proof of principle: does the intervention have the intended treatment outcome with respect to the object of treatment? Then come studies to test large-scale efficacy. Studies are broadened to test whether—when the intervention is delivered by a large group of practitioners to a larger group of patients—it still has the intended treatment outcome. Lastly, researchers study an intervention’s effectiveness. What meaningful benefit accrues to patients, their ability to function well in society, and their quality of life?

Whyte highlighted a number of elements of the definition of translational research as translating the findings of basic research into medical practice and thus meaningful health outcomes. Basic research encompasses not just the typical understanding of basic research as dealing with the cellular level, but also basic cognitive science. Medical practice involves assessing both cognitive status and interventions used. Meaningful health outcomes spans impacts of interest to a wide range of individuals including the patient, his or her caregivers and social support networks, payers of the health care, and policy makers.

Obstacles to Translation

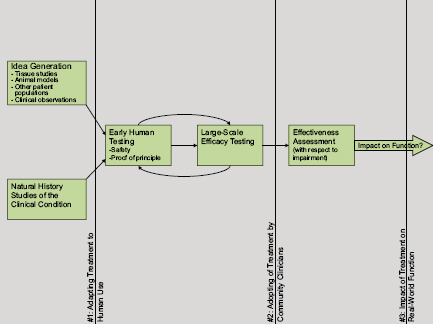

Looking again at the Phases 0 to IV of translational pipeline, Whyte discussed the nodes at which translation can stall (Figure 3-1). He cited little risk of stalling at Phase 0, which includes idea generation and natural history studies of the clinical condition. The first potential obstacle comes at the point of adapting early studies to human use—assessing safety and carrying out proof-of-principle studies. Accomplishing this is often an iterative

FIGURE 3-1 The translational pipeline and potential barriers to translation.

SOURCE: Whyte presentation.

process, looping from early human testing to large-scale efficacy testing and back again, as the research narrows in on an efficacious intervention. Once evidence of efficacy has been established, a second barrier emerges: to assess effectiveness involves creating and assessing behavior change among clinicians, a potentially difficult task. A final obstacle is determining whether the improvement of a specific impairment has practical utility, and if so, to whom?

Treatment Theory and Enablement Theory

Whyte discussed two types of theories related to human function: treatment theory and enablement theory (Box 3-1). Treatment theory specifies the mechanism by which a proposed treatment affects its immediate treatment target, defining the essential ingredients of the treatment that are required to effect the change in the object. The effect of the treatment may be moderated by additional active ingredients, but the essential ingredient

BOX 3-1 Theoretical Frameworks for CRT for TBI

Treatment Theory

A theory that specifies the mechanism by which a proposed treatment changes its immediate treatment target, defining the essential ingredients of the treatment that are required to effect the change in the object.

Enablement Theory

A theory that specifies the causal interrelationships among variables at different levels in the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health.

Treatment Object and Treatment Target

A treatment object, a component of treatment theory, is the immediate (proximal) outcome of an intervention. A treatment target, a component of enablement theory, is a clinically important treatment outcome and is often distal to the treatment object.

Active Ingredient and Essential Ingredient

An essential ingredient is the component of a treatment that the treatment must have in order to make a predicted change in the treatment object. An active ingredient is a component of a treatment that also moderates the treatment’s effect but that is not, itself, required for the treatment to change the treatment object.

Mechanism of Action

The means by which an essential ingredient brings about a change in the treatment object.

is what defines the treatment and distinguishes it from other treatments.1 In rehabilitation, the set of treatment theories is heterogeneous, with theories hailing from a wide range of fields including physiology, social theory, bioengineering, and many others.

To illustrate the use of a treatment theory and the clarity that it can offer, Whyte gave examples of CRT treatments as well as familiar, physical treatments. He described the use of progressive resistance exercises to increase muscle strength. In this case, the object of the treatment is to increase muscle strength or torque, and in order to accomplish that—the part played by the essential ingredient—there must be repetitive contraction of the muscle and an increasing load. The use of a treatment theory dictates

_____________________

1There may exist a difference between Whyte’s terminology and terminology more commonly used among CRT researchers. Whyte used “essential” and “active” ingredients according to the above definitions; however, during much of the workshop discussion the participants used “active ingredient” seemingly as the equivalent of Whyte’s “essential ingredient.”

that the treatment be defined not in terms of the specific intervention, but in terms of the essential ingredient. In this example, the treatment is not defined in terms of the specific manipulations, but rather in terms of the use of any manipulation that involves repetitive contraction of the muscle and an increasing load. All treatments that do those two things would be considered the same treatment. Examples from CRT include neutral cues for goal neglect and hemi-dressing training.

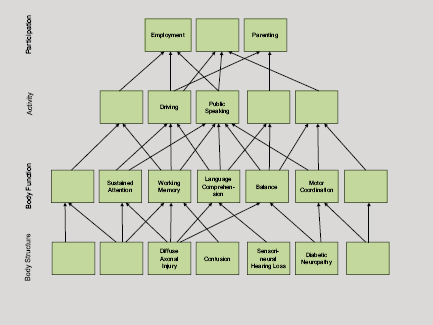

Enablement Theory

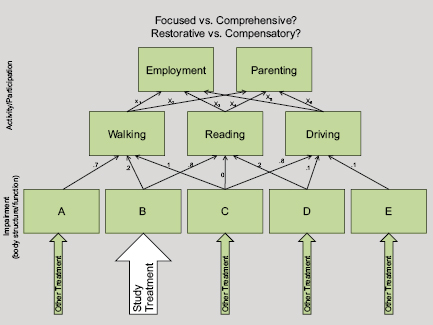

Whyte described enablement theory, which addresses the causal relationships among variables at different levels in the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF), which separates function into several levels, including tissue, organ function, and personal activity, and social integration (Figure 3-2). Each functional level has a different level of analysis and different attributes, and each is covered by treatment and/or enablement theory.

FIGURE 3-2 Enablement theory.

SOURCE: Whyte presentation.

FIGURE 3-3 The intervention under study in the context of the enablement theory. Example of relationship among variables in International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health framework, at impairment (body structure/function) and activity/participation levels.

SOURCE: Whyte presentation.

Enablement theories pose a bigger-picture question: If we improve a particular impairment, what effects will that have elsewhere in this system of human functioning? The outcome of an enablement theory is a treatment target, a clinically important treatment outcome that is often distal from (removed or more complex than) the more immediate treatment object.

Enablement theory specifies the location of the arrows (see Figure 3-3) between different levels of pathology and impaired function, as well as the arrows’ relative weight. Enablement theory produces conceptual models that take into account the complex interrelationships between more basic types of functioning, such as sustained attention or good motor coordination, and higher-level functioning, such as holding down a job or parenting a child. With enablement theory, a higher-level function can be broken down into lower-level functional components.

Whyte described how treatment theory and enablement theory can bring distinct and complementary tools to a research agenda.

Treatment theory constrains the definition of a treatment, informs researchers’ understanding of what kinds of patients might respond to a given treatment, and informs the selection of appropriate outcome measures to determine efficacy. He described that treatment theory tells you whether a treatment should or should not succeed at changing its “direct object,” which may or may not translate into “effectiveness” in the sense of meaningfully improved function (as in the example of successfully strengthening leg muscles in two patients, one of whom has a terrible balance problem). The strengthening may only be “effective” in promoting community mobility in the patient with good balance.

In contrast, enablement theory provides no tools for change (and is indifferent to how change is made); rather, it predicts the effects that a specific intervention will have elsewhere in the ICF—that is, at levels above (see Figure 3-3) that at which the intervention was made. An important contribution of enablement theory is that it informs subject selection for effectiveness research. This is because enablement theory informs the selection of the patients in whom treatment is most likely to result in effective outcomes. In addition, it helps researchers to trace the various functions that together contribute to a higher, more complex function, and to look at whether they have treatment options for other lower-level functions that also support the desired higher-level function.

Placebos

Whyte contrasted the use of placebos in drug studies and in behavioral research, discussing how true placebos are impossible to come by in behavioral studies. A placebo must be fully plausible but guaranteed to be inert. In pharmaceutical research, in which the active ingredient is known and consists of a specific molecule, the use of a placebo allows the researcher to control for all other variables. In behavioral research it is very hard to mask the active ingredient because the interventions involve the performance of meaningful tasks. For example, patients concerned about memory generally know whether the researcher is talking about memory or something irrelevant for memory. Consequently, researchers must decide at each stage of research what confounds they are most concerned with—whether it is the natural recovery process, or patient or clinician bias—and control for them in specific ways that do not rely on placebos.

The Maturation of Research

Whyte outlined an example of a research strategy following the maturational process, highlighting where and how treatment and enablement theory play a role.

In an early stage of research involving proof of concept, the reliance is exclusively on treatment theory. The researcher is investigating whether the essential ingredients act on the treatment object in the manner hypothesized; he or she is not yet focused on the intervention’s effect on clinical outcomes. At this stage the intervention is being optimized in terms of delivery, dose, and impact, and the outcomes measured will be those most tightly tied (the most proximal) to the intervention. The researcher is developing and modifying the treatment protocol and moving it toward a manual. In terms of patient selection, the treatment theory will dictate the kinds of patients who are likely to demonstrate the most powerful and measurable impact on the treatment object under study. Even at this early stage, Whyte described how a comparison group might be called for, especially if the research is focused on the acute stage of recovery, in which rapid natural recovery is happening concurrent with the treatment. Other questions related to research design involve natural history (where are patients on the spectrum of spontaneous recovery?), and how visible are the treatment ingredients and therefore how much blinding is realistic and, if it is not, how should bias be handed?

Second Stage: Efficacy Studies

Once the initial research has shown the intervention to work as intended in a small group of patients, the next stage in the maturational process involves efficacy studies in larger groups of patients and with interventions delivered by a larger number of practitioners. These studies are still largely guided by treatment theory. At this point, the treatment becomes more formalized, and manuals and training algorithms are developed. Researchers aim to verify that the intervention affects the treatment object in a broader sample of patients and facilities, they further explore safety considerations, and they may look for early evidence of impact on clinically important outcomes in specific populations. Study participants are patients who will benefit from improvement in the treatment object as well as in some proximal clinically relevant targets. Questions in play at this stage of research design include: What are appropriate comparison treatments at this point? Does the dosage need to be adjusted or the manual changed? What are the appropriate—relatively proximal—distal outcome measures?

Third Stage: Two Types of Effectiveness Research

The third stage described by Whyte is research on the effectiveness of the intervention in routine application. He suggested dividing effectiveness research into two areas. One is by the traditional definition of effectiveness: Does the treatment have the same effect on the target when delivered by a wide range of practitioners in the field (i.e., people who may lack specialized training and practice far from academic centers of research)? This definition of effectiveness is still focused on the treatment object. The second type of effectiveness to be assessed is more rehabilitation specific, namely, the effectiveness of an intervention on distal clinical outcomes. This strand of effectiveness research relies mainly on enablement theory. It is no longer a question of whether the treatment’s effects are strong enough, but rather the question is in whom can this treatment alone deliver major clinical benefit, and in whom can this treatment deliver major clinical benefit if it is provided in combination with specific other treatments?

Key questions for research design at this point include

- What kinds of patients are likely to routinely receive this treatment?

- What kinds of facilities are likely to routinely deliver it?

- Are there characteristics of patients and facilities that might moderate how effective the treatment is and that we should be measuring?

Regarding the treatment itself and optimal comparisons, it may be more relevant to compare it to the standard of care or to what is current in practice than to make a theoretically driven comparison. Regarding effectiveness, outcomes related to the object of treatment will continue to be measured, and, in addition, outcome measures will be added that are more distal and are connected to closely related targets of treatment. Research designs will need to assess overall effectiveness at the level of distal impact that is realistic. This includes evaluating patients that experience broad impact from the treatment alone as well as when the treatment is given as part of a package. If a package of treatments is given, then an algorithm is needed to decide what treatment(s) each patient receives.

Regarding this third stage, Whyte noted that it can be increasingly difficult to do randomized clinical trials, and researchers may need to rely more heavily on health services research. Whyte suggested that, as the Military Health System considers introducing certain CRT interventions, one thing it might consider is to introduce them systematically and in staggered fashion in order to produce naturalistic evidence of the effect of those interventions.

Whyte recognized that not all behavioral research follows this methodical sequence. Some treatments are in wide use with little theoretical foundation. Likewise, other treatment packages are in wide use, while little is known about which specific ingredients are most important and for which patients. Some treatments are effective at the group level but differ in their effectiveness for individual people; moderating variables are in play that are poorly understood.

Whyte noted that for CRT to be rigorously shown to be effective, it will require multiple studies, and the goals of those studies will and should differ over time as the research moves through the maturational process. Using treatment theory and enablement theory in combination can guide study designs so researchers do not place unrealistic requirements on treatments while at the same time being most likely to capture the treatment benefits when they exist. He emphasized that, whether or not a research program is moving methodically through the above steps, this outline of the maturational process for CRT is useful as a reference point and for guiding researchers to regularly ask (1) Where along the path does this treatment dwell right now?, and (2) What questions need to be answered in order to move it forward?

GUIDELINES FOR CREATING MEANINGFUL DESCRIPTIONS OF CRT INTERVENTIONS

Current State of Practice

Marcel Dijkers, Senior Investigator, Brain Injury Research Center of Mount Sinai Hospital, discussed common descriptions of rehabilitation interventions, focusing on their generality and arguing for greater specificity in order to more efficiently advance a broader research agenda. Therapy descriptions of the most general type specify only the number of hours provided and the type of health care professional who provided them (e.g., 2 hours of physical therapy and 6 hours of occupational therapy). Descriptions are also often given in terms of the intended outcome (2 hours of gait therapy) or theoretical orientation (2 hours of neurodevelopmental therapy). None of these descriptions gives information about the nature, intensity, or quality of the teaching; manipulations; or instructions delivered by the therapist.

Dijkers spoke about a review that he and colleagues performed of published reports of intervention studies in which they found that the number of words used to describe the research outcomes far surpassed the words used to describe the interventions themselves. Descriptions of interventions

generally covered the number of hours, the number of sessions, the discipline of the therapists, and the setting; the details of the treatments remained virtually invisible.

Dijkers cited a literature review of 95 randomized clinical trials that sought to determine the effective elements of interventions in terms of patient and treatment characteristics, treatment goals, and outcomes, with a major focus on the content of the therapy (van Heugten et al., 2012). The authors found very little information about the actual content of the treatment, either in the papers reporting on the randomized clinical trials or in other papers by the same authors.

Attempts to Classify Rehabilitation Treatments

Dijkers explored several possible schemes for categorizing rehabilitation interventions. One option, medical subject headings, are useful for locating published work, but as descriptions for rehabilitation interventions they leave much to be desired. The category of “therapeutics” has a subcategory of rehabilitation, but the associated terms are very general and in some cases overlapping. The classification system of the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health has health services and health systems as subcategories of environment. Although CRT and rehabilitation are contained within these descriptions, the system lacks the specificity necessary to be useful. The ICF also characterizes patients’ treatments based on the targeted outcome. However, this also says nothing about what the intervention entailed. Even when the target constitutes the treatment, for example, in gait therapy in which the gait is improved by the patient’s practicing an improved gait, simply naming the target provides little useful information about the actual intervention.

An attempt was made within practice-based evidence studies funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research to compile lists of names given to interventions based on discussions among treatment providers. Providers supplied sets of names for the treatments they used that were expected to have an impact on patient outcomes. For TBI, lists of activities and interventions were drawn up, divided by type (e.g., physical therapy and psychology). But in neither case were the terms specific enough to shed any light on what the intervention consisted of.

Dijkers discussed treatment typologies in health care, including Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED). He found Current Procedural Terminology problematic for CRT-related terms because it sometimes gathered together interventions under one code that warranted separate codes and, conversely, it sometimes split multiple interventions among different codes when they ought to have shared just one. SNOMED’s terminology system suffered

from similar issues. The nursing intervention classification system goes into greater detail with regard to interventions, each one of which is labeled, defined, and described using from 1 to 20 specific nursing activities. This system includes an array of activities and interventions specific to TBI, approaching usefulness much more closely than do the previous classification schemes. However, this system remains too general to contribute much to the advancement of research on CRT for TBI.

More Promising Ways of Describing Rehabilitation Treatment

Dijkers turned to what he and others view as essential components of a framework that will allow researchers studying CRT for TBI to fruitfully describe, study, and communicate about their work. This framework was the same as that described earlier by John Whyte and centered on specifying essential ingredients, those attributes of the treatment that bring about changes in the object of treatment (and that often are the basis for naming the treatment) through a hypothesized mechanism of action. The changes in the object of treatment may cascade to more distal outcomes in the treatment target. Dijkers highlighted the usefulness of separating (proximal) objects of treatment from (distal, higher-level) targets of treatment, noting how a single treatment target (e.g., the patient dressing him- or herself) may be addressed by multiple means, through different objects of treatment.

When classifying interventions, while researchers often think in terms of ingredients (and mechanisms), practitioners think first in terms of objects (and targets) of treatment—what problem does the patient have, and how can it be improved? Dijkers suggested that rather than classifying interventions by the ingredients, researchers might consider classifying them first by the object and then using subcategories consisting of different sets of ingredients.

Content of Interventions and Dose

Dijkers discussed dose and dosage as a way to think through important issues concerning active ingredients. In the pharmacological model that informs the current notion of dosage, the active ingredient is a molecule and dosage is defined in terms of quantity of the molecules given per certain characteristics of the patient—body weight, severity of disease or disorder, and so on. However, to apply the notion of dosage to CRT raises a number of questions that have not yet been investigated. Is any dose of CRT beneficial? Is there an optimal amount or intensity of CRT? When does CRT end, and how do we decide?

Dijkers offered the example of a CRT intervention at his institution,

the Brain Injury Research Center of Mount Sinai Hospital, highlighting the concept of an active ingredient in action. His research team has a program providing remediation of executive function, attention training, and emotional regulation. A key element of the program is a strategy they have termed “SWAPS”:

- Stop.

- What is the problem?

- Alternatives?

- Pick one and plan.

- Satisfied?

When a patient is faced with a problem, he or she applies SWAPS, and Dijkers proposed that SWAPS is the active ingredient. To sharpen the definition of this CRT intervention, Dijkers drew on work by Steven Page’s research group that proposed “intensity,” “dosing,” and “delivery method” as key elements of stroke motor rehabilitation (Page et al., 2012). Dijkers also highlighted a set of papers recently published in the International Journal of Speech and Language Pathology on optimal treatment intensity (motivated by the question of the appropriate point at which to discharge a patient). One paper defined “treatment intensity” as the number of repetitions of an active ingredient delivered during a treatment session and discussed optimal treatment intensities. It was followed by journal-solicited comments and critiques from practitioners in a variety of fields, and then by a second paper by the original authors describing how they saw the state of the field and discussing why establishing the optimal intensity of an intervention is difficult (Baker, 2012). Dijkers recommended these papers as examples of sound thinking on the questions of dosage, but noted that the authors had not begun to think in terms of active ingredients and how to quantify, measure, and operationalize them—indicating that even they had a long way to go before arriving at a research design capable of constituting a solid step along the translational pipeline. To date, there have been no studies that have elucidated the effective dose needed to achieve a given outcome at the termination of treatment and whether this dose needs to be altered if desired effects are to be maintained over time.