Examples of Surprise

The committee discussed a number of different examples of surprise, ranging from an adversary’s potential deployment of disruptive technologies against naval operations (such as specific “Day 0” cyber offense payloads), to the potential interruption of critical supply chains (such as for rare-earth elements), to the potential unfolding of national security-related geopolitical events (such as regional economic instability). The committee also reviewed case studies of previous surprises and the circumstances leading up to the surprises and will discuss several of these in its final report for illustrative purposes. Examples of some intelligence-inferred surprises and disruptive technology and tactical surprises are provided in Box 1; however, these examples should not be viewed as a definitive list of all the types of surprises naval forces might face.

BOX 1

Some Examples of Surprises

Examples of Intelligence-Inferred Surprises

- Cyber intrusions (e.g., programmable logic computer worms).

- Ballistic missile attacks (e.g., medium-range ballistic missiles).

- Use of uninhabited vehicles (e.g., semisubmersibles for attacks).

- International security and cooperation (e.g., nuclear weapon proliferation, economic instability, cultural/tribal/religious conflicts).

- Denial of access to space (e.g., jamming, use of antisatellite weapons).

Examples of Disruptive Technology and Tactical Surprises

- Use of synthetic biological weapons.

- Use of small nuclear weapons.

- Use of highly energetic sources.

- Use of improvised explosive device triggers.

- Social media utilizations.

In addition to reviewing previous case studies of surprises, the committee has, so far, selected the following three surprise scenarios, which it believes are important to U.S. naval forces, as starting points from which it can examine, illustrate by example, and, ultimately, recommend potential changes as requested in the study’s terms of reference:8

- Scenario 1: Denial of access to space;

- Scenario 2: An asymmetric engagement with complex use of cyber attacks in a naval context; and

____________________

8In addition to the surprise scenarios listed in this interim report, the committee anticipates further illustration of surprise in the final report by examining additional scenarios, such as potential nonkinetic effects to counter missile magazine limits, and the potential impact of unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) to represent both a surprise threat and opportunity.

- Scenario 3: A “black swan” event for which the front-end scanning and prioritization framework for mitigating surprise (to be described) is not applicable.

Surprise Scenario 1 (intelligence-inferred surprise): Potential loss of access to space due to antisatellite capabilities and electronic or optical countermeasures, including loss of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) feeds, communications, navigation (GPS), and timing (also GPS). The loss of access to space scenario has been broadly discussed in the open media.9 In particular, U.S. naval warfighting systems depend heavily on positioning, navigation, and timing. In essence an adversary, in denying U.S. forces’ access to space, could employ the following measures against U.S. space assets, either simultaneously or with unpredictable frequency to render those assets unreliable:

- Jamming U.S. combatant or weapons GPS receivers within the line-of-sight of adversary surface and airborne platforms,

- Cyber attack on command and control centers and combatants,

- Jamming or dazzling surveillance sensors to obscure U.S. orbital ISR observations,

- Jamming of communications reception by satellite receivers within the receive antenna’s main beams or side lobes,

- Jamming of satellite downlink receivers within the line-of-sight of adversary surface or airborne combatants or weapons, or

- Kinetic engagement of orbital systems.

The committee also recognizes that cyber attacks or other interference in this scenario could originate from imbedded threats in commercial off-the-shelf hardware and software that are widely deployed in present naval systems and could render naval systems and networks inoperable at a critical moment of need. The heavy dependence on certain widely used satellite communications operating in frequency bands that can be more readily jammed is a particular concern. Jamming of communications and denial-of-service attacks are clearly an intelligence-inferred surprise that can be mitigated with alternatives.10

For the final report, the committee intends to explore the broader issue of an anti-access/area denial environment, one element of which is the loss of access to space. Such an enquiry will allow for further examination of the following issues:

____________________

9For example, see Background Briefing on Air-Sea Battle by Defense Officials from the Pentagon, News Transcript, U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, November 9, 2011; available at http://www.defense.gov/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=4923, accessed May 9, 2012. See also Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes, 2012, “Asymetric Warfare, American Style,” Proceedings of the Naval Institute, April, pp. 24-29; Andrew Erickson and Amy Chang, 2012, “China’s Navigation in Space,” Proceedings of the Naval Institute, April, pp. 42-47; and David Fulghum, 2012, “Under Siege: Foreign Countermeasures Proliferate as U.S. Electronic Warfare Programs Falter,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, April 9, pp. 22-23.

10The issue of cyber defense for U.S. naval forces will be covered more extensively in an upcoming NSB study, commissioned by the CNO, and anticipated to be ready in the first quarter of 2013.

- Potential gaps between missions that could provide openings for surprise, e.g., between strike, antisubmarine warfare defense, antisurface warfare defense, and air defense capabilities, as well as the complexities of multiplicative use of every asset from every mission area to “take out” a Navy aircraft carrier;

- New concepts of operations for emerging advanced new capabilities such as low-observable, unmanned aerial vehicles; precision strike; 5th generation air; Mach 3+ air, high-speed, and surface threats;

- Potential novel uses of nonkinetic, rapidly reconfigured assets such as electronic warfare, especially in the context of “red versus blue and blue versus red”;

- Implications for logistics chain protection;

- Potential cultural expectations and blind spots;

- Use of social media in a propaganda strike in an attempt to influence attitudes at home and even debilitate a nation’s will to fight; and

- The role of surprise tactics.

Surprise Scenario 2 (disruptive technology and tactical surprise): Potential consequences of social media crowd emergence that could place U.S. personnel and property at risk in foreign areas or threaten U.S. domestic infrastructure. The committee has begun to explore the potential implications of population unrest, whether spontaneous or induced, in which social media is used to turn a local population against the United States and to facilitate coordinated search and engagement of U.S. citizens and U.S. assets on the ground in a manner not unlike some of the uses of social media during the Arab Spring.11 This is an area that may require a combination of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and perhaps creation of a new situation awareness capability, especially as it might apply to naval ships or other U.S. naval personnel operating in foreign ports. This scenario is also a mechanism for examining the complexities of attempted cyber manipulation of a crowd’s mood and actions, and it provides a context for considering potential effects of surprise in on-the-ground and coastal operation of naval forces.

Surprise Scenario 3 (“black swan” surprise): Black swan (self-inflicted and/or natural disaster) surprises include a full range of potential actions that might have a significant impact on the capability of U.S. naval forces. These include events such as acts of nature (e.g., tsunamis, earthquakes, or disease outbreaks), as well as surprises that might evolve from actions such as national strategic decisions and/or national budget priority changes. Examples of national strategic decisions include the recent decision to deploy the U.S. Coast Guard to remote areas of global conflict and the earlier U.S. naval forces humanitarian assistance/disaster relief response to the 2010 catastrophic earthquake in Haiti.

____________________

11See Lisa Anderson, 2011, “Demystifying the Arab Spring,” Foreign Affairs, May/June. Available at http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/67693/lisa-anderson/demystifying-the-arab-spring. Accessed May 12, 2012.

In addition to data gathering and discussions that helped the committee formulate the three surprise scenarios described above, the committee also received briefings from exemplar programs that appear quite capable of timely anticipation of and response to surprise. In this interim report, the committee applies the above three surprise scenarios and three exemplars—the Navy SSBN Security Program, the Air Vehicle Survivability Evaluation Program (Air Force Red Team), and the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense Program—as example cases to help illuminate the following:

- Impediments that currently exist for certain areas of potential surprise outside of mainstream acquisition programs that may be hampering anticipation and response;

- Successful principles and infrastructures that might be integrated into already existing naval organizational structures and processes to address the broader realm of potential surprises;

- Structures and processes that could accommodate the above three examples of unaddressed/under-addressed surprises (denial of access to space, flash mob activity via social media, disaster response);

- Key capabilities, policies, and metrics that support successful structures and processes for dealing with surprise; and

- Potential changes to better prepare for, and be more resilient in the face of capability surprise for naval forces.

These concepts, and opportunities for improvements, are explored and integrated below.

A POTENTIAL NAVAL FRAMEWORK FOR DEALING WITH SURPRISE

Complexities in Dealing with Surprise

The committee has observed and acknowledges the challenges and complexities for naval forces in dealing with potential capability surprise as exemplified in the above three surprise scenarios. In each of the three scenarios, various stakeholders (e.g., operational, intelligence, technical, and acquisition related) should be involved in raising awareness of potential vulnerabilities that capability surprise could expose. Likewise, different entities should be responsible for prioritizing, resourcing, exercising, and developing TTPs against such scenarios. For example, entities ranging from Atlantic and Pacific Fleets, to the Office of Naval Intelligence, to the Office of Naval Research may be involved in scanning for potential surprise. Entities ranging from laboratories to naval operating forces, U.S. Marine Corps Combat Development Command (MCDDC), Navy’s OPNAV N2/N6 and N9 organizations, and the Program Executive Offices have key roles to play in prioritizing and developing responses and assuring readiness. Although many stakeholders are involved, there is currently no designated lead working across the Navy to ensure not only recognition of potential capability surprises, but also the required integration and prioritization of efforts to help mitigate their negative impact. A supporting infrastructure or lead integrating authority that can rapidly work through the complexities and that cuts across various naval authorities does not, in most cases, appear

to exist.12 It is crucial to understand that to be effective, counter-surprise efforts not only must scan for and address new or emerging technologies but also must anticipate and search for the use in unforeseen ways of technologies and capabilities that already exist. The Navy must scan for other countries’ military exercises, doctrine, and publications as well as technologies.

A Model for Dealing with Potential Surprise

Despite the above complexities, a positive factor is that the committee has been briefed on example programs that have demonstrated the ability to anticipate and respond to surprises with material solutions that are timely, even within the currently acknowledged process-laden, acquisition system. These “exemplar programs” are (1) the Navy SSBN Security Program,13 (2) the Air Vehicle Survivability Evaluation Program (Air Force Red Team),14 and (3) the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program (whose responsiveness was exemplified by the shoot-down in Operation Burnt Frost of a wayward National Reconnaissance Office satellite.15 The principles and key “ingredients” for dealing with potential capability surprise in each exemplar program are similar: a stable program and infrastructure; a capability thread that includes research and technology development, modeling and simulation, expert staff, acquisition and industrial capability, and testing infrastructure; and very visible senior leadership support and top cover. Furthermore, several organizations, including the U.S. Marine Corps expeditionary forces, the U.S. Coast Guard operations for responding to natural disasters, OSD Rapid Prototyping, and the Joint Interagency Task Force-South (JIATF-S) organizations, have each developed remarkable resilience for anticipating and responding to rapidly developing, on-the-ground needs.16 Key common attributes of these successful programs will be discussed and developed more fully as the committee continues its data-gathering work toward producing a final report.

____________________

12The potential impact of a recently announced OPNAV structural reorganization, creating the N9 as a single baron to oversee warfighting programs is a step towards providing structure that may help mitigate capability surprise. The impact of this new structure will be explored further as this study progresses. For additional information on this realignment see “CNO Realigns OPNAV Staff,” Navy Office of Information, March 3, 2012; available at http://www.navy.mil/search/display.asp?story_id=65845. Accessed May 24, 2012.

13Stephen C. Schreppler, Andrew F. Slaterbeck, and CAPT Christopher J. Kaiser, USN, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, N97, “SSBN Security Technology Program,” presentation to the committee, April 12, 2012, Washington, D.C.

14Christopher Roeser, MIT Lincoln Laboratory, “Air Force Red Team Overview,” presentation to the committee, May 16, 2012, Washington, D.C.

15RADM Brad Hicks, USN, Program Director, Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense, “Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense: Press Briefing, March 19, 2008,” presented to the committee by RADM Joseph A. Horn, Jr., USN, Program Executive, Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense, and Conrad J. Grant, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, May 16, 2012, Washington, D.C.

16Benjamin Riley, Director, Rapid Prototyping Technology Office, and Principal Deputy, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Rapid Fielding, “Rapid Prototyping Perspectives,” presentation to the committee, February 29, 2012, Washington, D.C, For additional information on the OSD Rapid Prototyping Office, see National Research Council, 2009, Experimentation and Rapid Prototyping in Support of Counterterrorism, National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

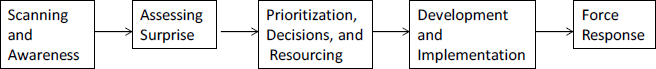

To help guide the approach and understanding needed to address potential capability surprise for U.S. naval forces, the committee has developed a functional framework, shown in Figure 1, consisting of five phases that can be aligned with the development functions, accountabilities, and principles observed in the exemplar programs noted above.

FIGURE 1 Five phases required for mitigating capability surprise. This is a continuous process in which each element informs the other. For example, Force Response adjustments may generate a loop-back in the process. Further reaction to a tactical or Black Swan surprise may enter one of the three right-most phases depending on the nature and timing of the required response.

The five phases—(1) scanning and awareness; (2) assessing the potential for surprise; (3) setting priorities, decision making, and resourcing; (4) development and implementation of tactics and capabilities; and (5) force response—are discussed below. All are necessary to successfully anticipate or react to potential or real surprises. Specifically, the first three phases allow for the impact of a surprise to be assessed, with either a high or low priority as the outcome. In phase 4, several outcomes are possible, including the development of new tactics. At the same time, there is a natural tendency to implement a “quick and dirty” partial solution between phases 4 and 5, and to ignore the limitations that the solution may leave as residual risks to operations. Accordingly, the adequacy of proposed responses should be assessed before any outcome emerges from phase 5.

In the context of the two classes of surprise previously noted, the first three phases would help naval forces better anticipate intelligence-inferred surprises. On the other hand, natural disasters whose occurrence may have been anticipated, but not at the scale of a black swan event (e.g., the March 2011 Fukushima disaster), would enter the framework at phase 4. Moreover, events in-theater may require tactical or strategic operational adjustments in phase 5 as a result of assessing the adequacy of proposed responses.

Scanning and Awareness

Phase 1—Scanning and Awareness—involves scanning the horizon for potential technologies, technical applications, and operational behaviors that could cause surprise, which is defined here as “an adverse event whose outcome is worsened by lack of preparedness or awareness to counter unexpected developments.” The committee’s initial data gathering confirms that certain capabilities are already available to anticipate surprise, including the Office of Naval Research-Global (ONR-G) global science and technology network and the technical intelligence provided by the Office of Naval

Intelligence (ONI).17 Integration of these and other broader capabilities can inform a potential risk spectrum relating each potential surprise to the standard measures of “likelihood of occurrence” and “operational impact if such an event transpired.” More specifically, the committee believes that collaboration among operational, intelligence, and technical experts to fully vet which capability could become surprises, and in what timeframe, in the context of standard risk framework would significantly increase awareness.

Assessing Surprise

Phase 2—Assessing Surprise—includes such key items as effective modeling, simulations analysis, and “red teaming.” The somewhat over-used term “red teaming” is applied here to emphasize the dynamic tension required of the operational, technical, and intelligence communities to flesh out potential negative impacts of surprise and prioritize which should be addressed in each timeframe, from short term through long term. Key to the success of this process is application not only of operational experience and campaign-level modeling as it is used currently, but also of the more detailed system- and physics-level modeling, coupled with experiments, as necessary, to determine feasibilities and maturity levels of the potential surprise events as well as their potential operational impacts. Further, the cultural thinking of potential adversaries must be part of the red team formulation. This assessment process must inform decisions about use of resources in subsequent phases.

Prioritization, Decisions, and Resourcing

Phase 3—Prioritization, Decisions, and Resourcing—includes strategic naval planning, budgeting, and evaluation of policy implications for executing a response to the prioritized risks identified in phase 2, and budgeting and allocating resourcing for the response. Here, naval commands with resources must possess the span of control in rapid prototyping, development of tactics, acquisition program adjustments, and force introduction to ensure that the vetted, validated risk response priorities are implemented in a timely manner. A key element that this authority should expect of the assessment process is that first priority will be given to making use of existing systems and capabilities, perhaps with modifications. Such an approach would minimize the expectation of new-start programs that consume much more time and funds.

____________________

17Walter Jones, Executive Director, Office Naval Research, discussion with the committee on the operations of ONR-Global, February 29, 2012, Washington, D.C. Also, Wayne Mason, Chief Scientist, Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), “Capabilities Surprise: S&TI Perspective,” presentation to the committee, February 28, 2012, Washington, D.C.