Overview

The Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) traces its origins to the establishment of the Manufacturing Technology Centers Program in 1989.1 This program was developed as a part of the nation’s response to the perceived decline in position of the United States vis-à-vis Japan as a leading manufacturer of high-technology goods. Located within the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), MEP has offered technical and business support primarily to the nation’s small and medium-sized manufacturers. Two decades later, the rapid rise of China as a global locus of manufacturing is once again raising concerns about U.S. competitiveness.2 To address these concerns, MEP is seeking to refine and adapt its mission to encourage product innovation and commercial development among the nation’s manufacturers. In its own words, it has begun a transition from “reactive” strategies to the “proactive pursuit of increased profits and overall growth.”3

_______________

1Senator “Fritz” Hollings of South Carolina introduced legislation that led to the establishment of the Manufacturing Technology Centers (MTC) Program through the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). This program started in 1989 with regional centers in three states—South Carolina, Ohio, and New York. The mission of these regional centers was to support the transfer of manufacturing technology to improve the productivity and technological capabilities of America’s small manufacturers. The number of centers grew rapidly to provide services to all 50 states and Puerto Rico, and, in 1998, the program was re-named the Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP). Senator Hollings maintained his support for the MEP Program through his retirement in 2004 when, in his honor, it was re-designated the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership. Source SC-MEP at <http://www.scmep.org/history/>.

2President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, Report to the President on Ensuring American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing, Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, June 2011, page 1. The PCAST report notes that “The United States was the world’s leading producer of manufactured goods from 1895 through 2009; some experts estimate that China surpassed the United States as the leading manufacturing country last year.” Access at <http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/pcastadvanced-manufacturing-june2011.pdf>.

3Manufacturing Extension Partnership, The Future of the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership, Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, December 2008, <http://www.nist.gov/mep/upload/MEP_NextGenStrategy-2.pdf>.

Box A

The Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership

The Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP), administered by NIST within the Department of Commerce, has sought for more than two decades to strengthen American manufacturing.

Mission. MEP’s mission is to “act as a strategic advisor to promote business growth and connect manufacturers to public and private resources essential for increased competitiveness and profitability.”

Program Scale. In 2012, the NIST Manufacturing Extension Partnership had a budget of $128 million. The total NIST-MEP headquarters staff numbers some 45 people who focus on setting strategy, evaluating the needs and demands of clients, helping facilitate the development of tools, and “gluing together the Centers into a network that can share best practices.” NIST funding is matched 1:2 by individual state Centers, using funding primarily from state governments and client fees. The nationwide network includes some 1,300 staff supported by over 2,300 third-party service providers, and the overall budget for the MEP system was about $300 million in 2012.a

Decentralized Structure. NIST-MEP works cooperatively with organizations that include non-profits, state government agencies, and universities to complete the MEP mission. In all, some 60 MEP Centers are located across the country, with Centers in every state. They vary widely in structure and operating strategy. Pennsylvania, for example, has seven Centers; many states have only a single MEP Center. California, which accounted for 13 percent of the nation’s manufacturing GDP in 2011, has two MEP Centers serving the state. The work of these Centers is further dispersed among some 300 field offices. The Centers rely heavily on local partners to design and deliver services that are tailored to the needs of the manufacturing clients.b

Evolving Focus. According to then MEP Director Roger Kilmer, “Part of our evolution was to change from offering a technology push, where we knew about which technologies work in a federal lab, to looking at what manufacturers really needed. It also meant learning to look at the entire manufacturing enterprise—not just the tech piece of it, but everything else: the financing, workforce development, marketing, and sales.” From an early focus on off-the-shelf manufacturing technologies, basic technical assistance, and plant layout, MEP evolved towards “lean production” in response to demand from companies. The program continues to adapt with a new emphasis on growth and on innovation, reflecting the need for firms to be more proactive in an increasingly competitive world economy.

aRoger Kilmer, “MEP’s Place in the Innovation Chain,” presentation at the November 14, 2011, National Academies Symposium.

bMEP centers are structured in various ways. “Most MEP centers are not-for-profit (501(c)(3) corporations affiliated with state governments or universities.” U.S. Government Accountability

Office, “NIST Manufacturing Extension Partnership Program Cost Share,” GAO-11-437R, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2011.

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES STUDY OF MEP

In his opening remarks at the workshop, Philip Shapira, the chair of the National Academies committee that is overseeing the analysis of MEP program, noted that the study would review and assess the performance of MEP program, including the ways in which states use the program, the diversity of the users, and issues of funding and co-funding. From a user’s perspective, he added, the study would also gauge how the program is used by manufacturers and how well it relates to their needs.

Dr. Shapira observed that the Academies study is also an opportunity to shed new light on several “deeper” questions. “Our companies are competing with companies around the world,” he said. “MEP is one of the major ways in which we are trying to stimulate our small and medium-sized manufacturers to be productive, to export, and to train productive workers. In this era of global competition, we need to ensure that MEP is configured in such a way that it can meet not only these current challenges, but future challenges as well.”

THE IMPORTANCE OF A STRONG U.S. MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

As MEP Director Roger Kilmer noted at the workshop, MEP’s new focus on innovation and competitiveness reflects the importance of manufacturing to the nation’s economic growth, job creation, exports, and innovation.4 Dr. Gregory Tassey of NIST and Dr. Sridhar Kota, then of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, also underscored the relevance of a robust manufacturing sector for the United States in their workshop remarks.

A Source of High-quality Jobs

In his presentation, Dr. Tassey noted that “manufacturing contributes $1.6 trillion to GDP, and employs 11 million workers,” with many of the

_______________

4A recent assessment by the Department of Commerce makes the point that a vibrant manufacturing sector is important for the health of the U.S. economy. Further, the report sets out why strong measures are needed at both federal and local levels to support its continuing strength. U.S. Department of Commerce, The Competitiveness and Innovative Capacity of the United States, Washington, DC, January 2012. The report states that in 2009, manufacturing made up 11.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) [Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Survey of Current Business 2006-2009,” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, January 2011] and that 9.1 percent of total U.S. employment, 4 directly employing almost 12 million workers [<http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2011/01January/0111_indy_accts_tables.pdf>].

manufacturing jobs providing above average pay and benefits.5 The manufacturing sector also has powerful indirect employment effects on other sectors of the U.S. economy, supporting millions of additional supply chain jobs across the economy.

An Important Source of R&D

Dr. Tassey noted that manufacturing companies in the United States represent 11 percent of GDP but are responsible for 67 percent of R&D performed by business and industry. Reflecting this, the sector employs 57 percent of the nation’s industrial scientists and engineers.6 “If you remove manufacturing, you have decimated the research infrastructure of the private sector,” and while some service industries do a moderate amount of R&D internally, that amount “pales in comparison with the amount done by the manufacturing sector.”

Largest Contributor to U.S. Exports

As an economic sector, manufacturing is the largest contributor to U.S. exports.7 In 2010, the United States exported over $1.1 trillion worth of manufactured goods, accounting for 86 percent of all U.S. goods exports and 60 percent of U.S. total exports. However, as Dr. Tassey pointed out, “we have not had a trade surplus in manufacturing in 35 years.” Every year of a deficit, he said, detracts from the economy’s GDP, and the projections for GDP growth in the future are “not particularly robust.”

Linkages to Innovation

A strong manufacturing sector is also of central economic importance because of its strong linkage to innovation. In his presentation, Dr. Kota highlighted the importance of sustaining an “industrial commons,” a term he said that describes the complex and enduring partnerships among manufacturers, universities, technical colleges, firms, research institutes, financing entities, and other links in the supply chain. He drew attention to recent reports by the

_______________

5“Total hourly compensation in the manufacturing sector is, on average, 22 percent higher than that in the services sector. About 91 percent of factory workers have employer-provided benefits, compared to about 71 percent of workers across all private sector firms.” See Executive Office of the President, A Framework for Revitalizing American Manufacturing, Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, 2009, <http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/20091216-manufacturing-framework.pdf>.

6National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Research and Development in Industry: 2006-07, NSF 11-301, Arlington, VA, 2011, Detailed Statistical Tables. Available at <http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11301/>.

7In order to stimulate the creation of additional jobs, President Obama’s National Export Initiative has set the ambitious goal of doubling U.S. exports by the end of 2014.

President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology that emphasize “the critical importance of advanced manufacturing in driving knowledge production and innovation in the United States.”8

The Importance of Proximity

Dr. Tassey stressed the importance of understanding the strong linkage between innovation and manufacturing; numerous benefits flow out of the co-location of design, research, and production, as well as from other links in the value chain.9 Dr. Tassey emphasized that the fast-growing high-tech services sector must have close ties to its manufacturing base to fuel innovation. “There are definite co-location synergies between services and the sources of their technology,” he said. Those working in a manufacturing supply chain find increasingly important interactions with workers in related activities. “These co-location synergies flow between the tiers of the supply chain and ultimately the hardware and software that are used by the service industries.”10

Manufacturing Capacity and National Security

In his presentation, Dr. Kota affirmed that a key goal of the Obama Administration’s Advanced Manufacturing Partnership is to “jumpstart domestic manufacturing capability essential to our national security.” As the military comes to rely more heavily on complex and advanced technology systems, retaining the capacity and knowledge necessary to manufacture these goods in the United States becomes more important. The ability to source critical infrastructure components, from communications equipment to power

_______________

8Department of Commerce, U.S. Competitiveness and Innovation Policy,” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, January 2012, page 6-2. See also President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, Report to the President on Ensuring American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing, op. cit.

9A recent MIT wide research effort reaffirms the importance of proximity to manufacturing and innovation. From extensive interviews with managers at small and medium-sized U.S. manufacturers, the MIT researchers found that these companies “often repurpose existing technologies or techniques and apply them to make new products. And they often bundle products together with services—thus blurring the boundary between the manufacturing and service industries. They conclude that proximity and collaboration matter in this sphere: “A key to innovation for these firms is being located in a diverse industrial ecosystem that offers many complementary resources, such as training and opportunities for collaborative research.” Suzanne Berger et al, A Preview of the Production in the Innovation Economy Report, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013.

10See the summary of Gregory Tassey’s remarks in this volume. In its 2011 manufacturing report, the PCAST states: “Proximity is important in fostering innovation. When different aspects of manufacturing—from R&D to production to customer delivery—are located in the same region, they breed efficiencies in knowledge transfer that allow new technologies to develop and businesses to innovate.” President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, Report to the President on Ensuring American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing, op. cit., p. 11.

generation also affects our ability to protect against disruptions in the supply chain.11

RECENT DECLINES IN U.S. MANUFACTURING

While manufacturing continues to play a vital role in the U.S. economy and is a major source of employment, the U.S. manufacturing sector has faced significant challenges in recent decades.

A Shrinking Fraction of U.S. GDP

In her workshop remarks, Dr. Ginger Lew, formerly of the White House National Economic Council, reminded the participants of how much ground the U.S. manufacturing sector has lost to foreign competition in recent years. In the 1950s, manufacturing’s share of the GDP peaked near 30 percent. Today its share is about 11 percent, a decline that accelerated after 2007. The United States is still the world’s largest manufacturer, with a global share of about 22 percent of global output, she said, but “it faces more challenges from around the world.” There is a growing awareness in this country that thriving manufacturers are critical to America’s economic recovery. “As the President has said, we’ve got to go back to making things.” The United States cannot completely move into a knowledge-based and services-based economy, she said; it also has to produce tangible assets.

Decline in Manufacturing Employment

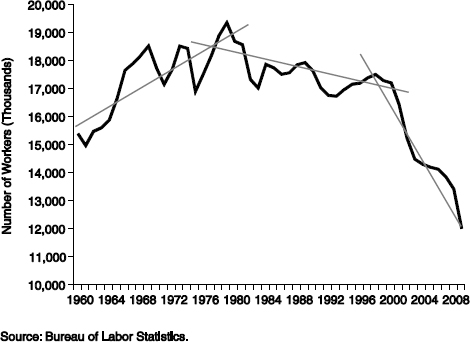

Mark Rice (President of the Maritime Applied Physics Corporation and member of the MEP Advisory Board) and Dr. Tassey both noted in their workshop presentations that employment in the U.S. manufacturing sector has declined by about 8 million in the past 26 years.12 In the past decade, employment levels in manufacturing have declined steeply by about one-third. (See Figure 1.)

_______________

11Department of Commerce, U.S. Competitiveness and Innovative Capacity, op. cit., Chapter 6.

12This information is based on data prepared by the U.S. Census. Access at <http://www.ces.census.gov/index.php/bds/sector_line_charts>. For additional information, see Robert D. Atkinson, Explaining Anemic U.S. Job Growth: The Role of Faltering U.S. Competitiveness, Washington, DC: The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, December 2011.

FIGURE 1 U.S. manufacturing employment: 1960-2009.

SOURCE: Gregory Tassey, Presentation at November 14, 2011 National Academies Symposium on “Strengthening American Manufacturing: The Role of the Manufacturing Extension Partnership.”

They noted that, in part, this decline is the result of greater competition from low-wage countries, leading to the off-shoring of low-skilled jobs to lower-cost locations.13 Manufacturing employment fell by 16.1 percent from 2003 to 2009, before recovering by 4.6 percent to end 2012.14

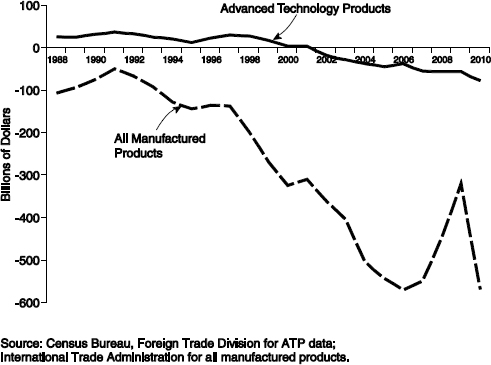

Growing Trade Deficit

These employment and wage trends also roughly coincide with the increased foreign competition faced by the U.S. manufacturing sector. As Mark Rice and Gregory Tassey noted in their workshop presentations, the United

_______________

13For example, one study has shown that between one-quarter and more than one-half of the lost manufacturing jobs in the 2000s are the result of import competition from China. See David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hansen, “The China Syndrome: The Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition,” Cambridge, MA: MIT Working Paper, 2011; <http://www.mit.edu/files/6613>. Some of this decline is conventionally described as due primarily to increased efficiencies and productivity gains, though the basis for this view has been questioned by Susan Helper and Susan Houseman, among others.

14Bureau of Economic Analysis. Access at <http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CES3000000001?data_tool=XGtable>.

States continues to lose ground in key manufacturing sectors, including those sectors that are likely to drive our economy in the future. Until 2002, the United States ran a trade surplus in “advanced technology products,” which includes biotechnology products, computers, semiconductors, and robotics. By 2010, however, the United States ran an $81 billion trade deficit in this important sector.15 This represents a very significant shift. (See Figure 2.)

The Impact of Off-shoring Manufacturing

Dr. Tassey observed in his workshop presentation that much of the trade deficit in advanced technology is attributable to the phenomenon of progressive off-shoring over the past few decades. First, U.S. manufacturers began by setting up manufacturing facilities abroad, either to be near growing markets, to make use of skilled, low-cost labor, or both. The offshore facility did

FIGURE 2 U.S. trade balances for high-tech vs. all manufactured products, 1988-2010.

SOURCE: Gregory Tassey, Presentation at November 14, 2011 National Academies Symposium on “Strengthening American Manufacturing: The Role of the Manufacturing Extension Partnership.”

_______________

15U.S. Census, Trade in Advanced Technology Products, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, 2010, <http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c0007.html>.

a small amount of R&D in order to move products into the market. As the host countries provided more of the skilled labor, they began to gain R&D experience and expand their internal R&D infrastructures to capture synergies at the “entry” tier of the high-tech supply chain. For example, Taiwan and Korea became skilled at producing electronic components, while China excelled at assembly. In this way, those countries gradually became competitive in their own sub-markets.16

Hollowing Out of U.S. Supply Chains

As economies specialize in a particular tier of the high-tech supply chain, they begin to integrate backward along the supply chain, taking more value-added from the Western economies, including the United States. Dr. Tassey maintains that this “hollowing out” of supply chains has cost the United States in terms of wealth creation, high-value jobs, and technology sales. Although the United States had been the “first mover” in developing many commercial technologies, “poor technology life-cycle management” has led to a gradual loss of market share in products such as oxide ceramics, semiconductor memory devices, semiconductor production equipment, lithium ion batteries, flat-panel displays, robotics, and advanced lighting.

Forward Integration in Asia

Many emerging economies have begun to integrate forward along supply chains. For example, said Dr. Tassey, Taiwan has integrated forward from electronic components into electronic circuits, and Korea has integrated forward from components to electronic products. These economies are beginning to integrate forward into services as well, so that co-location synergies are being lost by the United States and captured by others. An inference of this trend, he said, is that U.S. firms, including small and medium enterprises (SMEs), are not able to take advantage of significant manufacturing opportunities, including R&D, technology transfer, and other essential links of the supply chain.

THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT’S ROLE IN SUPPORTING MANUFACTURING

SMEs often play a significant role in introducing new technologies; the most successful of these firms find the technical and financial support needed to develop, test, scale up, and transfer a technology-based product to the marketplace. Too often, however, this does not happen—or is not achieved by a U.S. firm—even when the technology itself has clear value because of

_______________

16See Gregory Tassey, National Institute of Standards and Technology, workshop presentation in this volume. See also Gregory Tassey, The Technology Imperative, Edward Elgar, 2009.

information asymmetries in the market. This classic “market failure,” as Phillip Singerman of the National Institute for Standards and Technology pointed out, provides a basis for a role for government support. Dr. Singerman also observed that “the nation has not had a coherent manufacturing policy before,” but argued that given the challenges facing the manufacturing community it is time “to develop a more sophisticated and nuanced model of innovation for the policy discussion at the federal level.”

Support for Applied Research

In his workshop presentation, Dr. Kota noted that U.S. firms have excelled in being first to acquire knowledge, thanks in large part to the steady production of good ideas though substantial and sustained federal investments in basic research. However, U.S. policy has been less successful in supporting the application of new ideas through engineering and the commercialization of new products in the market, Dr. Kota said. The United States has lost out in many cases to foreign competitors whose governments have devoted more resources and policy support for these two stages of innovation.

Disseminating Knowledge and Building Links

In this regard, Dr. Kota noted that the Manufacturing Extension Partnership could play an important role in advancing the nation’s manufacturing competitiveness through disseminating and accelerating the use of modeling and simulation tools by SMEs. He added that MEP could also help SMEs bridge the skills gap by encouraging small manufacturers to engage with community colleges and Original Equipment Manufacturers. By being the first to identify challenges and then find the resources to address these challenges, Dr. Kota said that MEP Centers can “serve as a glue” between the small and medium manufacturers and the resources that are being developed by the Advanced Manufacturing Initiative—a plan to “support innovation in advanced manufacturing through applied research programs for promising new technologies, public-private partnerships around broadly-applicable and precompetitive technologies, the creation and dissemination of design methodologies for manufacturing, and shared technology infrastructure to support advances in existing manufacturing industries.”17

_______________

17See the opening letter to President Obama from the PCAST Chair and Co-chairs in the June 2011 PCAST report, President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, Report to the President on Ensuring American Leadership in Advanced Manufacturing, op. cit.

Box B

A New Strategy for Manufacturing

In his remarks, Dr. Kota highlighted A Framework for Revitalizing American Manufacturing, a report issued by the White House in December 2009 that lays out the Administration’s strategy to revitalize U.S. manufacturing. The strategy addresses key issues such as cost drivers, access to capital, training and education, tax policies, and investments in technology. The report notes that “the key to success [in manufacturing] lies in American workers, businesses, and entrepreneurs—but the federal government can play a supportive role in providing a new foundation for American manufacturing.”a

aExecutive Office of the President, A Framework for Revitalizing American Manufacturing, Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, 2009, p. 11.

NEW CHALLENGES FOR MEP

To adapt to the competitive challenges of the twenty-first century, MEP Director Roger Kilmer said that his organization would work to encourage innovation by manufacturers. Historically, he said, MEP has focused on promoting lean manufacturing, quality, and cost effectiveness. While those are still key services delivered by MEP Centers, they are considered today to be one important element of a broader portfolio.

The new challenge, he added, is to look at the other side of the business ledger: “How do I grow the company? How do I get new sales with existing products? How do I get into new markets by exporting? Most important, how do I develop new products either by working with new supply chains or technologies built into other things I currently do?” He said that these new concerns have been summarized under five key areas:

• Continuous improvement.

• Technology acceleration.

• Supplier development.

• Sustainability.

• Workforce.

An essential point, he said, is that all of these functions are interrelated and must be developed in an integrated fashion. “When we’re working with a company, it is not just about the supply chain piece or the workforce piece. All of those have to be built into a strategy the company can implement.”

Helping Small Manufacturers Adapt

A challenge for manufacturers today, Mr. Kilmer said, is to sort through the many programs available to manufacturers to find what is most useful. Most assistance programs are designed for large manufacturers, who already have the resources to make changes and benefit from them. “A lot of it has to do with how we get to a strategic level with small and medium-sized manufacturers rather than just fixing problems,” he said. Addressing the needs of small manufacturers is important because, as MEP’s Gary Yakimov pointed out at the workshop, SMEs represent some 99 percent of all manufacturing establishments and employ 10.2 million people, about 70 percent of all manufacturing employment. These smaller firms, he said, account for about 57 percent of the value added by all U.S. manufacturers.

Expanding Supply Chains

In her workshop remarks, Susan Helper of Case Western Reserve University noted that rapid changes in global economies have brought pressures on SMEs to change rapidly. For example, many large manufacturers now depend on SMEs for an increasing range of supply chain activities. For example, about a third of suppliers to the U.S. automobile industry are firms of fewer than 500 employees that are expected to provide products once produced in-house.

In his remarks at the workshop, Joseph Houldin of the Delaware Valley Industrial Resource Center noted that outsourcing does create opportunities for SMEs and reallocation of value within the chain, but it also means that new functions are “pushed down the value chain” to SMEs, including more R&D, logistics work, and just-in-time production. SMEs either may see these requirements as part of a larger opportunity to develop new customers or as a web of challenges too complicated to deal with. MEP, he said, can help a company work its way through such questions.

Addressing Productivity Challenges

SMEs are also under pressure to raise productivity. As Gary Yakimov noted, a substantial and growing productivity gap between large and small firms has been observed, with SMEs lagging larger firms. This productivity gap, as value added per employee, grew from about $12,000 in 1967 to about $80,000 in 2002. Over the long run, this trend is not sustainable. Small manufacturers will face increasing international competition, and to compete they must become more agile, develop better marketing skills, and find profitable niches in lengthening supply chains. These global pressures are a principal driver of MEP’s new strategic thrust to help companies innovate, enhance their marketing capabilities, and export.

Growing SME Innovative Capacity

According to Philip Shapira, smaller firms typically lack market power and are often cautious about adopting innovations. This hesitation is not surprising given “the real risks of business failure and constraints of knowledge, expertise, and finance.” “While policy narratives focus on entrepreneurial high-technology firms,” he added, “these are only a small minority of all SMEs in the economy. Many small firms operate in traditional or resources-based industries, serving the lower ends of supply chains and subcomponent operations. Many are ‘lifestyle’ or family-run operations.”18 In this regard, as Mr. Kilmer noted in his workshop presentation, a key objective of MEP is to increase the innovative capacity of a broad range of manufacturers.

Introducing New Tools and Concepts

In her workshop remarks, Dr. Helper drew attention to recent research on what manufacturing firms need to do to become more innovative.19 She noted that MEP can play a valuable role in instilling “high-road techniques” that harness everyone’s knowledge—not just that of top executives—to achieve innovation, quality, and variety.20 Dr. Helper called this “agile production,” by which a firm can design, set up, debug, and produce a variety of products quickly—“just in time.” She observed that in the face of knowledge-based global competition, “production can no longer rely on a fixed division of labor because the product mix changes constantly; it must employ people who can do more than one job, because no one knows what the next job is going to demand.” As value per employee is added, it is used to pay the workforce, invest in new capital and equipment, and deliver profits to the owners. A key top-line strategy for high-road firms, she said, is to design their own products.

Dr. Helper said that her study findings also reinforced the value of continuous improvement. This calls for distributed knowledge for workers at all levels; the more people on the shop floor who understand the purpose of what they are doing, the better they understand the importance of debugging and other improvements of the manufacturing process. Firms that employ continuous improvement practices, such as quality circles, suggestion systems, and preventive maintenance, must also be able to design a higher percentage of their own products, do more R&D, and improve processes quickly.

_______________

18Dr. Shapira’s comments reflected research published in P. Shapira, Product and Service Innovation: Report to the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Atlanta, GA, and Arlington, VA: Georgia Tech Program in Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy, and SRI International, 2006.

19See S. Helper, T. Krueger, and H. Wial, Why Does Manufacturing Matter? Which Manufacturing Matters? A Policy Framework, Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, February 2012, <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2012/2/22percent20manufacturingpercent20helperpercent20kruegerpercent20wial/0222_manufacturing_helper_krueger_wial.pdf>.

20Susan Helper, Renewing U.S. Manufacturing: Promoting a High-Road Strategy, Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 2008. Access at <http://www.sharedprosperity.org/bp212/bp212.pdf>.

Training Center Staff

For MEP to promote, bridge, and facilitate connections between innovation, manufacturing, and the sustainable growth of SMEs, its staff need to be trained and equipped appropriately. At a symposium question-and-answer period, Diane Palmintera of Innovation Associates observed that while many Center directors applaud the effort of MEP to move toward innovation and technology, their staffs are not always prepared to coach firms on tech transfer and innovative technologies. MEP’s Mr. Kilmer agreed, and said that the NIST-MEP has been working on a training curriculum related to innovation. “Quite honestly,” he said, “it’s a difficult thing for the centers. Some staff will be able to make those changes, and some won’t. We try to equip them with training and professional development, but it is a challenge.”

Improving Outreach

As several speakers noted, MEP faces unique challenges in reaching out to a diverse mix of small firms spread out over the country. According to Philip Shapria, small firms exhibit “great heterogeneity in enterprise characteristics, resources, motivations, sectoral and regional attributes and other factors, and concomitant wide variations in orientation toward and capabilities to undertake innovation.”21 Challenges exist at the firm level, industry level, within the context of social infrastructure, and in the innovation environment. There are internal company barriers, with SMEs lacking information, experience, training, resources, strategy, and confidence to adopt new technologies. There are also external barriers in the costs of vendors, customers, consultants, and other business assistance sources that might be useful to SMEs.22 For these reasons, as James Watson of California Manufacturing Technology Consulting noted in his workshop presentation, simply reaching those SMEs best positioned to take advantage of MEP advice is difficult.23

Identifying and Sharing Lessons Learned

Finally, MEP, as a national program, faces the challenge of developing and sharing the best practices across the system. As Mr. Kilmer noted, “MEP’s role in this innovation chain is really to advise the manufacturer, helping it to

_______________

21P. Shapira, “Innovation and small and midsize enterprises: innovation dynamics and policy strategies,” in R. Smits, S. Kuhlmann and P. Shapira, eds., Innovation Policy: Theory and Practice. An International Handbook, Cheltanham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2009.

22A. Caputo, et al, “A methodological framework for innovation transfer to SMEs,” Industrial Management and Data Systems 102(5):271-283, 2002; P. Shapira, “U.S. manufacturing extension partnership: Technology policy reinvented?” Research Policy 8(3):66-72, 2001.

23Supporting this conclusion, recent data commissioned by MEP found that the MEP national network only provides in-depth assistance to 9 percent of the available market of companies with 20-499 employees that are willing to seek out and invest in outside support.” Stone and Associates, “Re-examining MEP Business Model,” October 2010, p. 7.

assess different opportunities and challenges to make strategic decisions. The Centers also need to be connectors that can help small and medium-sized manufacturers find the other resources and components it needs.”

MEP’S EVOLVING ROLE

How is MEP addressing these challenges? Several speakers at the workshop noted that MEP’s role has evolved from an emphasis on lean production to a focus on enhancing the innovative capacity of manufacturers. Philip Shapira observed that “originally, these Centers were created to transfer federally sponsored, state-of-the-art technology to firms. Later they started delivering pragmatic assistance, appropriate to state and local conditions, with business services, quality systems, manufacturing systems, information technology, human resources, engineering, and product development—the ‘soft’ business practices.”24 Today, as MEP’s Gary Yakimov noted, the principal goal of the partnership is to increase the competitiveness and productivity of U.S. manufacturing by helping manufacturers in the United States improve production performance and by helping manufacturers grow their business by making the right product for the right customers profitably.

Building Local Innovative Capacity

Echoing these themes, Mr. Kilmer noted in his remarks that while the founding focus of MEP was to promote lean manufacturing, quality, and cost effectiveness, these early activities are now considered not “the end of the journey, but the beginning.” NIST-MEP has come to believe that cost efficiency alone is not sufficient, and that companies needed to think about growth strategies as well. MEP’s overarching strategy today is to increase the innovation capacity of manufacturers so as to drive profitable sales growth. Part of our evolution,” said Mr. Kilmer, “was to change from offering a technology ‘push,’ where we knew about which technologies work in a federal lab, to looking at what manufacturers really needed in the field. It also meant learning to look at the entire manufacturing enterprise—not just the tech piece of it, but everything else: the financing, workforce development, marketing, and sales.”25

Supporting Local Resources

MEP’s decentralized organization allows each Center, within certain operational and performance parameters, to customize its organizational model, service offerings, and delivery mechanisms based on the needs of its clients and

_______________

24P. Shapira, J. Roessner, and R. Barke, “New pubic infrastructures for small firm industrial modernization in the USA,” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 7:63-84, 1995.

25See the summary of Roger Kilmer’s presentation in the Proceedings chapter of this volume.

the institutional capabilities within its service region.26 While this diversity among MEP Centers is “a little confusing to us at the national level,” said Mr. Kilmer, “the key thing is that manufacturers now recognize local entities as the source of their manufacturing assistance.” MEP Centers themselves may function as advisors, consultants, and/or matchmakers, helping small manufacturers address their short-term needs in the context of a long-term business strategy.

Dr. Shapira noted that a key challenge for MEP is to reach out and stimulate individual firms to innovate in sustained fashion. “You can’t force firms to change, but you can encourage them, point them toward resources, mentor them, and stick with them. Change is not a one-time event.” It was important to note, he said, that the strong partnership orientation means that each MEP takes on the regional flavor where it is located. “That adds opportunity and complexity into the mix,” he said, “because every state does its partnership a bit differently, and in this review we want to understand how.”

Encouraging Cluster Growth

MEP can play an important role in strengthening the innovation clusters that are seen by many as important to the revitalization of U.S. technological leadership.27 In his conference remarks, Dr. Sridhar Kota observed that other federal agencies can and do help with the development of new technologies through public-private partnerships. But “once you have a technology, the MEPs play an important role in terms of business and technical assistance. The MEPs do even more in adding to the value chain, simulation, prototyping, and thinking about scaling. We already have MEPs, and they can help us.” Illustrating this point, Ms. Petra Mitchell of the Catalyst Connection, a Pennsylvania-based MEP Center, described her organization’s T-RIC, or Technology Acceleration in Regional Innovation Clusters Initiative. The objective of this program, she said, is to develop a consortium of regional clusters focused on accelerating technology within the small manufacturers in the region.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE MEP STATE CENTERS

Illustrating the differentiated nature of the partnership, speakers from the MEP Centers in Minnesota, Ohio, California, and Pennsylvania described the importance of manufacturing to their state or region’s economy and the role

_______________

27For a review of current clustering strategies and approaches, see National Research Council, Clustering for 21st Century Prosperity: Summary of a Symposium, C. W. Wessner, rapporteur, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2012. See also National Research Council, Growing Innovation Clusters for American Prosperity: Summary of a Symposium, C. W. Wessner, rapporteur, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

their organization plays in growing this sector. They also provided their perspective on the value of the federal MEP program to their local initiatives.

Minnesota

In his remarks, Robert Kill of Enterprise Minnesota emphasized the importance of manufacturing to Minnesota’s economy. The state has more than 8,000 manufacturers that collectively create 15 percent of its jobs and 18 percent of its payroll. Employing about thirty professionals, Mr. Kill said that his organization pays special attention to helping small and mid-sized manufacturers succeed by providing business consulting services and by building connections to public and private stakeholders. After losing state funding eight years ago, Enterprise Minnesota endures as a non-profit consulting organization.

Currently, Mr. Kill noted, more than half of Enterprise Minnesota’s services are aimed at business growth. In turn, the organization has reduced its emphasis on such activities as lean manufacturing and quality management in favor of “idea engineering,” executive leadership, and other growth-enhancing activities. A simple focus on “lean-and-mean,” he said, would not bring the rate of growth that was needed for small and mid-sized manufacturers.

Mr. Kill said that his organization values its partnership with MEP. In particular, he cited the significance of the independent follow-up surveys required by MEP, which he said, is a key distinction separating it from other groups who offer consulting to small and medium manufacturers. “We go back to each client annually through independent third-party survey research to confirm each client's individual successes in sales increases, cost reductions, and profitable investments. MEP, our federal partner, requires this data as evidence of our value to each manufacturing client.”

Ohio

In her remarks, Beth Colbert of the Ohio Department of Development said that her state ranked fourth in the nation in manufacturing. Ohio has about 20,000 to 25,000 manufacturers, and “what’s important here” is that 98 percent of those employ fewer than 500 workers and so meet the criteria for NIST-MEP services. The state has some large manufacturers, she said, but is primarily a “supplier state” that provides inputs to large manufacturers. It ranks first in tier two and tier three companies, and in automotive suppliers. “So when the big guys go down,” she said, “we go down hard, too.”

Prior to 2008, the MEP system in Ohio operated multiple independent centers. In 2009, as part of a new strategy for economic development, these were merged into a partnership with the Ohio Department of Development, bringing a new statewide perspective. She said that the strategic plan “really sparked Ohio’s interest” because of its emphasis on continuous improvement, sustainability, workforce development, and technology advancement. At the

same time, the Ohio Edison Technology Centers were brought into the partnership. The Edison Centers had been created in 1984 by the Ohio legislature as a $20 million program operated by the Department of Development. Its mission is to fund centers and incubators for innovation and technology advancement by linking universities and industries.

With so many manufacturing suppliers in Ohio, the program divides them into three groups. These include (1) some 75-80 percent of all suppliers, who have little experience and can benefit from many forms of general manufacturing assistance; (2) about 10-15 percent of all suppliers, which require more specialized assistance; and (3) about 5-10 percent of all suppliers, a small group of experienced manufacturers that require “customized growth projects.” Ms. Colbert estimated that many firms in the first, largest group would benefit “almost immediately” from the basic programs and services of the MEP, such as cost-improvement training, financial coaching, general business assistance and trade and marketing assistance.

She said the state’s MEP program had found it did not have to try to offer every service to everyone, but could work in partnership with free or low-cost services for very small manufacturers. Many of these are found among the 88 state colleges and community colleges in the state as well as local partners and economic development groups that provide business services and have access to financing through local banks.

California

Mr. Watson, who leads California Manufacturing Technology Consulting (CMTC), began his presentation with a sketch of manufacturing in California, where about 44,000 manufacturers employ approximately 1.2 million workers. This number, he said, is down from 1.6 million at the beginning of the 21st century as the state lost companies to other states, including Nevada, Arizona, and especially Texas. Even so, he said, California remains the ninth largest economy in the world, and manufacturing will always be important in the state, which continues to have the largest concentration of manufacturers in the United States.

Mr. Watson described the CMTC’s new mission as “creating solutions for manufacturing, growth, and profitability.” CMTC provides a “comprehensive suite of services,” generated both internally by staff and externally by 50-60 third-party providers throughout the state. “We are essentially a one-stop shop, and when a manufacturer comes to see us, they don’t have to look somewhere else. We’ll help you run your business strategically from where you are today to where you want to go tomorrow, and you don’t need to step outside of CMTC.” CMTC does this, he said, through hands-on facilitation and coaching “both on the plant floor and in the board room.” CMTC also helps manufacturers partner with universities and junior colleges and colleges, and other business organizations. It also helps small manufacturers benefit from federal programs. In all, he noted, “we have

probably the largest network of third-party providers that handle manufacturing in the state.”

According to CMTC surveys, manufacturers had invested some $130 million in the past year. “That’s good for us,” he said. “I always like to see that because it means manufacturers are reinvesting in themselves, and the more they do that, the better they can compete and the more likely they are to stay in California.” The surveys had also revealed some $359 million in increased sales, which means “they are selling more than they were before. Our hope is that as sales increase, jobs will increase as well.” A final point from the survey was “a very high client satisfaction rating with our customers.” He said that this result had been recognized by the state, and the CMTC was now the “go-to organization” for anyone with manufacturing issues.

With regard to the role of MEP, Mr. Watson suggested that the partnership assist the various centers to share learning and integrate new initiatives. “This is all about pace and volume,” he said. “There are a lot of initiatives, and the challenge is how much and how fast can a Center absorb.” He said that by working together as a system and as Centers, all members would have access to the best practices. “The more we can share those best practices, the faster we can bring these initiatives to our customers and really take manufacturing back to where it needs to be for us to retain our leadership in the world.”

Pennsylvania

Petra Mitchell of the Catalyst Connection described her organization as a stand-alone, non-profit economic development organization in Pittsburgh and southwestern Pennsylvania. It was founded in 1988 and now has about 25 staff members. The Catalyst Connection receives less than half of its funding from state and federal programs; the rest is generated from fees, foundations, and other private sources. She calculated that $1.4 million in state investment has leveraged $3 million in additional funding.

Ms. Mitchell added that Southwestern Pennsylvania has about 3,500 manufacturers, which employ more than 100,000 people. The area is also home to about 25 universities and colleges, including the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University and 120 corporate or federal R&D centers. The economy is diverse, with a relatively low rate of unemployment. However, she noted that this diversity presents challenges for a small Center like the Catalyst Connection that seeks to offer manufacturing extension services across different types of manufacturing industries and sub-industries.

Ms. Mitchell said that her organization serves manufacturing clients by helping them improve staff skills through professional development as well as by introducing opportunities for networking and collaboration. Catalyst also seeks to develop new business opportunities such as those from natural gas

extraction from the Marcellus Shale.28 Catalyst also helps companies improve lean manufacturing and quality standards and provides a variety of business growth services to help companies find new customers, develop new products, and export products. It has helped firms with talent management, which has led to involvement with the Manufacturing Skills Institute, community colleges, and universities. Finally, Catalyst is developing a consortium of regional clusters focused on accelerating technology within the small manufacturers in the region. Current partners in this initiative include the University of Pittsburgh, National Energy Technology Laboratory, Innovation Works (a Ben Franklin Technology Partner), Pennsylvania Nanomaterials Commercialization Center, and AMTV, the Advanced Manufacturing Technology Ventures, LLC.

Ms. Mitchell said that she was “very proud” of the MEP system that she had been part of for 17 years, and was proud of the federal agency collaborations that had given her organization recognition, visibility, and standing in the development community. Going forward, she suggested continued emphasis on impact data and evaluation metrics. She also called for cohesive, system-wide goals that can help MEP achieve common purpose and direction. “We have many states, many Centers, and many stakeholders,” she said. At present, the Centers do most of their progress reports as individual Centers. “If we can create one set of goals and a common purpose, we can report on our progress as a system. How are we doing? I think we should celebrate our successes, because there have been many over the years.”

ASSESSING ACTIVITIES, OUTCOMES, AND IMPACTS

As MEP makes the shift from “lean production” to emphasize product innovation and commercial development, several speakers observed that new metrics would be required to assess its effectiveness. As Deborah Nightingale of MIT noted at the workshop, “Relevant and accurate measurement is critical during a time of transition to make sure that we are measuring the right kinds of things.” There are many different kinds of measurements, including outcome metrics and process metrics, which are quantitative, as well as qualitative metrics. As Dr. Nightingale further noted, “I think it’s going to be important as we move forward to really understand how and what we should measure so that assessments are aligned with the new strategy MEP is laying out.”

_______________

28The Marcellus Shale refers to a large formation of marine sedimentary rock that “extends throughout much of the Appalachian Basin. The shale contains largely untapped natural gas reserves, and its proximity to the high-demand markets along the East Coast of the United States makes it an attractive target for energy development.” Source: Wikipedia.org.

Box C

The Role of Partnerships for Manufacturing Around the World

A number of workshop participants made note of partnerships in other countries that seek to accelerate innovation through support for manufacturers.a Indeed, a number of other countries have generated their own versions of partnerships intended to accelerate the commercialization of technology. These technology extension services include the Kohsetsushi Center in Japan, the Fraunhofer Institutes and Steinbeis Centers in Germany, the Industrial Research Assistance Program in Canada, the Federación Espanola de Entidades de Innovación in Spain, and the Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Industrial in Argentina. A basic premise of these programs is that SMEs lack the resources of time, expertise, and finance to undertake all aspects of the innovation process, which can lead to suboptimal innovation investments and economic outcomes. Sources of support for these TES Centers range from mostly public funding (Japan) to mostly contract fees (Steinbeis).b

In his workshop presentation, Dr. Mark Rice observed that effective public-private partnerships are essential for bringing new ideas to the marketplace. “It needs to be linked to a strategy,” he added; “not a Fraunhofer strategy, or a Korean version, but an American strategy. The beauty of the American system is the diversity we bring to these problems. Let’s embrace that and figure out how to make it work on the local, state, and federal scales.”

aSee for example, remarks by Sridhar Kota, Gregory Tassey, Susan Helper, Mark Rice, and Robert James on Germany’s Fraunhofer institutes and Canada’s IRAP program.

bPhilip Shapira, Jan Youtie, and Luciano Kay, "Building Capabilities for Innovation in SMEs: A Cross-Country Comparison of Technology Extension Policies and Programs," International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 3-4: 254-272, 2011.

MEP’s Assessment Efforts

In his conference presentation, Gary Yakimov noted that that MEP’s performance has been reviewed on several occasions, with what he described as generally positive outcomes by the Office of Management and Budget, the National Academy of Public Administration (in 2003), and others. He noted, the assessment process has generally been considered thorough and detailed, and MEP officials have often been invited by other agencies to describe their techniques.

The Role of Surveys

According to Mr. Yakimov, MEP assessments provide a snapshot of its performance. He reported that a recent survey of client impacts for FY 2009

Box D

MEP Performance Metrics

As described by Mr. Yakimov, MEP has developed a performance metrics system that addresses performance at three levels:

System-level Metrics. This is the broadest level of evaluation, and includes productivity growth of SMEs, global competitiveness of U.S.-based manufacturers, supply chain efficiency, job opportunities for workers, and rates of business survival. It measures center performance in terms of costs, staffing, outputs, outcomes, and surveys. It also measures client impact and performance improvements. Metrics include cost savings, improvements in manufacturing systems, human resources systems, IT, marketing, sales, and company management. Based on Center data, MEP found that Centers contracted with 7,000 to 8,000 companies annually, through approximately 12,000 projects.

Center-level Metrics. Each Center has been reviewed annually, using a weighted scoring system that measures impacted clients, bottom-line client impact ratio, investment leverage ratio, percent of quantified impacts, and clients served per million federal dollars. These data are collected in part through the annual client survey (see below) and in part from data provided directly by each Center to NIST. Based on these metrics, Center performance improved substantially after 2004. A striking characteristic of the program, however, is the wide variation among Centers on almost all metrics. For example, in 2010 total expenditures per project hour in staff and contracted time ranged from $88 per hour in Mississippi to more than $1,000 per hour in eight other states.

Client-level Metrics and Performance Assessment. This level is based largely on an annual survey of MEP clients by Turner Research, a marketing and survey research firm. For FY 2009, about 8,900 MEP participants were queried, and 85.7 percent responded—an “incredible” rate, according to Mr. Yakimov. In response to planned MEP strategic changes, the survey began to change in January 2010. Notable changes include new tools to assess the increased focus on growth through innovation and the increased focus on market penetration.

New CORE Metrics. The new metrics, introduced in 2012, made a number of important changes: they replaced the previous pass/fail approach with a more graduated grading system; they sharply reduced previous dependence on the client survey without eliminating it; they added new qualitative metrics; and they focused attention for the first time on a range of indicators related to the provision of growth-oriented services.

was highly positive, showing $3.9 billion in new sales, $4.9 billion in retained sales, $1.9 billion in added capital investment, $1.3 billion in cost savings, and 72,075 jobs created/retained.

He added that this survey also asked clients about their three biggest challenges. The top responses were (1) ongoing continuous improvement / cost-reduction strategies, (2) identifying growth opportunities, and (3) product innovation and development. He said that this information could be interpreted in various ways. After all, every business wants to reduce costs—and yet this objective is not sufficient to fuel long-term growth or global leadership.

Putting these survey results in perspective, Mr. Yakimov recalled the famous remark by Henry Ford, who said that if he had relied on his customers for advice on the most promising growth opportunities, they would have asked him to build a faster horse. “I think one of the challenges we have across our system is to create a sense of urgency in small/mid-size manufacturers about the need to grow, innovate, export, and become more sustainable. What’s really important about this survey is whether we have products and services to meet this list of needs, and the fact is that we do, and we continue to develop them.”

Survey Challenges

Daniel Luria of the Michigan Manufacturing Technology Center, an experienced reviewer and participant in the development of the MEP program, noted that while the current evaluation system is logical, consistent, and works “passably well” in generating “large-seeming sum-of-impacts” that generally help the program and motivate Centers, it does less well when it asks MEP clients to compare their current situation “with an imagined situation without MEP services.” This difficulty is compounded by survey queries that require dozens of calculations to answer meaningfully. “For example,” said Dr. Luria, “one of the cost reduction questions is: ‘After working with a Center, how much lower are your labor, material, overhead, and inventory costs?’ Leaving aside the lack of agreement on a definition of overhead, and the problem that inventory costs are a one-time savings on the balance sheet, it is a very difficult question to answer.” Similarly, he said, the true role of outliers—i.e., Centers that substantially out- or underperform others—is difficult to understand because the survey looks only at changes with no reference to base levels.

While acknowledging that “ingrained habits” are likely to make it difficult to change the assessment techniques, he nonetheless argued that claims of MEP impact need to be based on changes in value added and productivity. The current evaluation does not address either question very well, he said, and does not tell Centers what they should be doing to increase these outcomes. Failure to do so “invites a reasonable presumption of near-zero net impact.”

Transitioning to a New Evaluation System

Mr. Yakimov said that in the transition to a new reporting and evaluation system, the MEP would continue to hold the individual Centers accountable for three things: financial stability, market penetration, and client/economic impact. “That model will never change, whether it’s the current system of evaluation or the new system.” The system in place through 2011 evaluates clients on new sales, retained sales, investment, cost savings, and jobs created and retained. The MEP holds the Centers accountable for these results, and evaluates them based on minimally acceptable impact measures (MAIM), annual and panel reviews, the operating plan, and quarterly data reporting.

The reason for the imminent change, he said, was that the MEP needs a “more balanced scorecard.” At the beginning of the MEP program, he said, the evaluation focused too much on documenting Center activities and its interactions with manufacturers. About a decade ago, the MEP moved to the client impact survey as the sole mechanism to hold Centers accountable. “I think what we want to do now is reach a balance between those two things. We want to look at the activities in addition to the outcomes and impacts.”

IN CLOSING

This workshop summary provides a variety of perspectives on how the Manufacturing Extension Partnership seeks to strengthen the nation’s small and medium manufacturers. This overview highlights key issues raised by speakers in the course of a National Academies workshop including, more broadly, the importance of manufacturing for the U.S. economy, the decline of the U.S. manufacturing sector, and the role that government can play in supporting this sector. More specifically, the workshop addressed the role of MEP in strengthening manufacturing in the United States, the evolution of MEP to address new global realities and opportunities, and the need for relevant metrics to shape this evolution. The next chapter provides detailed summaries of the presentations by each of the conference participants. The overall objective of the meeting and this volume are to enhance our understanding of the operations, achievements, and challenges of the MEP and the new strategies it plans to adopt to help small U.S. firms adapt to global competition.