Why: Why is a framework important to evaluation? A framework offers signposts for guiding the complex work of evaluation. It highlights the context, activities, and intended outcomes of evaluating progress in obesity prevention efforts.

What: What can be accomplished through this evaluation framework? The framework can help to guide the collection and analysis of data to inform progress and links these data to the planning and implementation of policies and programs.

How: How will the components of the evaluation framework be implemented? Of the components outlined in the framework, the Committee report recommends guiding principles, indicators of success, plans for national, state, and community evaluation, and improvements to the evaluation infrastructure.

The vision for evaluating progress in obesity prevention is clear: Assure timely and meaningful collection and analysis of data to inform progress in obesity prevention efforts at national, state, and community levels. However, realizing that vision requires hard choices: who will measure what, under what conditions, by what methods, at what costs, and for which user of evaluation information. Assets exist to build on, for example, our understanding of user needs, existing health objectives for the nation, an extensive literature and experience in program evaluation methods, and prior studies on accelerating progress in obesity prevention. The Committee identified several gaps, including a lack of guidance for core indicators and measures of success and lack of support systems for implementing evaluation activities at community, state, and national levels. In this chapter the term evaluation (or evaluation activities or efforts) will be used to include assessment, monitoring, surveillance, and summative evaluation.

Others have identified and reviewed models linking program and policy planning, implementation, and the various forms of evaluation associated with them (Gaglio and Glasgow, 2012; Green and Kreuter, 2005; IOM, 2010, 2012b; Tabak et al., 2012). The common element in these examples is their inclusion of or explicit focus on evaluation to inform decision making. Reviewing these and other models, in this

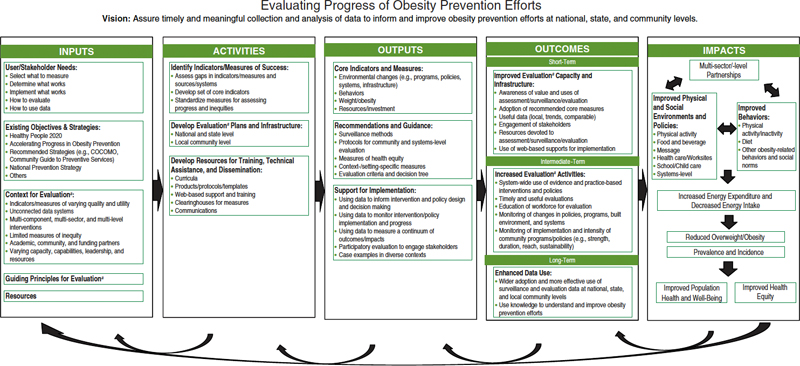

chapter, the Committee presents a framework for getting from here to there: from our current context of unmet user and end user needs to desired outcomes—improved evaluation activities and data use in efforts to reduce obesity and improve population health and health equity. Figure 3-1 depicts the iterative and interactive process by which we can improve the nature and contribution of evaluation efforts. In the sections that follow, key issues and stepping stones for realizing that vision are outlined in these components of the framework: Inputs, Activities, Outputs, Outcomes, and Impacts.

COMPONENTS OF THE EVALUATION FRAMEWORK

Inputs

Inputs are the resources used to accomplish a set of activities and are considerations influencing the choice of interventions or activities. They are discovered, described, and quantified through the assessment phase of evaluation, and are the activities tracked through their implementation during the monitoring phase of evaluation. Inputs can include needs, priorities, and other contextual factors, such as demographics and available resources, relevant to the activities. To realize the vision of timely and meaningful collection and analysis of data for informing and improving obesity prevention efforts, key inputs include attention to (1) user/stakeholder needs and those of the population served (see Chapter 2 on user needs, and Chapter 7 on community assessment and surveillance); (2) existing objectives and strategies; (3) the context for evaluation; (4) guiding principles for evaluation; and (5) resources to support the activities (see Figure 3-1).

User/Stakeholder Needs

As detailed in Chapter 2, users and stakeholders refer to a broad and diverse group: essentially, anyone working at any level (federal, state, or community) who is involved in funding, recommending, legislating, mandating, designing, implementing, or evaluating obesity prevention policies or programs, or applying the information that comes from these evaluations. Their expressed needs and interests must be considered throughout the evaluation process to determine what to measure and how to implement, adapt, and use the data from the evaluation.

To more fully understand user needs, the Committee consulted a range of end users representing various sectors engaged in obesity prevention efforts, including those working in health organizations, government at multiple levels, business, health care, schools, communities, and academia (see Preface, Chapter 2, and workshop agenda in Appendix I for an acknowledgment of individuals consulted). The need most commonly endorsed was to know “what works” in preventing obesity: which programs and policies, singly and in combination, show evidence of effectiveness in changing behaviors and outcomes. Obesity is a complex problem, affecting the full range of age, socioeconomic, and racial/ethnic groups. As such, a single simple solution to fit all contexts will not be found.

End users, therefore, want three things: (1) evidence-based guidance in selecting the combination of interventions to have a greater collective impact, (2) evidence-based guidance that is informed by diffusion principles (e.g., an intervention’s complexity, relative advantage, or cost [Rogers, 2003]), and (3) processes for adding, adapting, and evaluating other promising interventions where evidence is not so firm or generalizable. These are important insofar as evidence-based practices were typically

FIGURE 3-1 Framework for evaluating progress of obesity prevention efforts.

NOTE: COCOMO = Common Community Measures for Obesity Prevention.

a Evaluation refers to assessment, monitoring, surveillance, and summative evaluation activities.

demonstrated to be effective under high-resourced conditions of scientific studies, not the low-resourced conditions typically present in communities and settings where they would be implemented (Green and Glasgow, 2006).

To increase the chances for achieving and detecting success in their context, users also need information on how to track essential components and elements of the intervention (what to implement and how to do so) and how to measure the continuum of outcomes and impacts relevant to their work. Finally, users also expressed the need to understand how to obtain and use evaluation-related data more strategically to inform and justify their obesity prevention efforts (see Chapter 2).

In addition to the expressed needs of those evaluation users who are serving existing programs nationally and some locally, the Committee addresses in Chapter 7 the processes by which community-level efforts in obesity control can undertake a community assessment of the status of their obesity-related problems, assets, and resources, and to put in place surveillance measures of progress to assess trends and progress in meeting their needs.

Existing Objectives and Strategies

Recommended, ideally quantified, objectives for obesity prevention provide clarity and specificity in what to expect from the obesity prevention interventions (policies, programs, services, or environmental changes) as they are evaluated. The Committee focused on sources of national and community health efforts, including Healthy People 2020 (HHS, 2010b), the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention (APOP) report (IOM, 2012a), the associated Measuring Progress in Obesity Prevention: Workshop Report (IOM, 2012d) and the Bridging the Evidence Gap in Obesity Prevention report (IOM, 2010). It also drew on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) work on the Common Community Measures for Obesity Prevention Project (the Measure Project) (Kettel Khan et al., 2009) and on the periodically updated Guide to Community Preventive Services1 from systematic reviews and recommendations of the Community Preventive Services Task Force. It consulted Bright Futures Guidelines (AAP, 2008) and the National Prevention Strategy (NPC, 2011) for well child care. Many of these quantitative goals can be regarded as “stretch objectives”; that is, they reflect what could be accomplished nationally or locally if what is already known is applied. An additional task for evaluation and measurement of progress is to discover needs, reasonable objectives, and promising interventions from innovations emerging in states and communities as they scramble to address the obesity epidemic in the absence of complete scientific evidence of the needs, problems, and effectiveness of interventions.

Healthy People 2020, the result of a federal interagency effort led by the Department of Health and Human Services, with voluntary, private, state, and community government input, outlines national objectives for improving the health of Americans, including those related to physical activity, nutrition, weight status, and maternal and child health (HHS, 2010b). The IOM Committee report (2012a) on APOP provided more specific system-wide goals and strategies to prevent obesity as well as guidance about indicators of progress in implementing the recommended actions at national and community levels. Five critical, cross-cutting areas of focus were identified for intervention: physical activity environments; food

_____________

1 For more information about the Guide to Community Preventive Services, see http://www.thecommunityguide.org (accessed November 11, 2013).

and beverage environments; message environments; health care and workplace environments; and school environments.

In 2009, the Measures Project, led by CDC, released recommendations for 24 community-based strategies for obesity prevention along with an associated indicator, data collection questions, and potential data sources to track progress on each strategy (Kettel Khan et al., 2009). Strategies were grouped into six categories: food and beverage availability; healthful food and beverage options; breastfeeding support; physical activity promotion and limiting sedentary activity among children and youth; community safety to support physical activity; and community coalitions for creating change in the key environments. Also, CDC’s Guide to Community Preventive Services provides timely updates to evidence-based recommendations for action on an array of public health issues, including nutrition, physical activity, and obesity prevention (Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2005, 2011; Truman et al., 2000).

The National Prevention Council, under the direction of the Surgeon General, published the National Prevention Strategy (NPC, 2011); priority strategies include healthful eating and active living. For each priority, the Strategy recommends target actions, key indicators, and 10-year goals. Grounded in a science base, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (HHS, 2010a) and Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (HHS, 2008) offer similar guidance. Other scientific and professional associations, such as the American Heart Association and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, also provide recommendations for obesity prevention.

Context for Evaluation Activities

Another consideration for evaluation activities is the context in which the interventions to be evaluated will occur. Context closely links with the concept of assessment (baseline data characterizing the problem) and surveillance (ongoing or periodic data collection, analysis, and interpretation). At the national or state levels, assessment might include surveillance to assess changes in obesity rates and monitoring of policy changes, and summative evaluation assessing the association of the two. At the community level, assessment might take the form of a system to monitor changes in interventions and the built environment over time.

The context for evaluation activities includes the how much of what, how, by whom, and by when stated in the objectives for each intervention or strategy. The “how much” is stated as a target percentage, mean, or rate. “What” may be singular or complex, often referring to multiple-component, multi-sector, and multi-level interventions to assure conditions for healthful eating and physical activity (IOM, 2012a). Comprehensive interventions provide challenges for “what” and “how” to evaluate. For a single intervention strategy (e.g., improve the quality of foods and beverages consumed), numerous indicators exist (e.g., consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lower-fat dairy, etc.). Furthermore, for a single indicator (e.g., consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages or fried foods), many potential measurement methods exist, including review of archival records (e.g., of sales), observations (e.g., food disappearance, plate waste), and behavioral surveys (e.g., food frequency questionnaire, 24-hour recall). Each indicator and its associated measurement vary in quality (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity), utility, and resource requirements. These factors must be considered when offering guidance for how to evaluate. The “by when” aspect of the health objective informs the timing of the evaluation activities, for example, whether annually or at some other time interval, and the anticipated prospect of observing progress after a given interval of time.

Efficiencies in evaluation activities can be achieved by connecting existing data systems to enable users to share data. For example, when such data are available and there are data sharing agreements, schools collecting weights and heights of children can make body mass index (BMI) data available to communities to help gauge progress in obesity prevention. Similarly, existing vendor sales data can sometimes be made publicly available for analysis of the purchase of foods and beverages targeted by interventions. A common gap is the lack of data specific to the level at which important intervention or policy decisions need to be made. For instance, there may be useful data at the state level, but not at the county, city, or neighborhood levels in which interventions are occurring and policies are emerging.

Finally, who conducts the evaluation activities is an important aspect of context. The workforce for obesity prevention is as diverse as the sectors engaged in this work; for example, it may include policy makers, urban planners, educators, as well as public health professionals. Academic, community, practitioner, and funding partners vary in capacity, capabilities, incentives, leadership, and resources, all of which must be considered in designing and assuring implementation of evaluation plans. Funders of programs and evaluation have called for participatory research and collaborative evaluation in recent years, recognizing the added value of evaluation when those who design and conduct programs and those who have the additional theoretical and measurement skills to interpret the evaluation evidence jointly produce the program and evaluation.

Guiding Principles for Evaluation Activities

The Committee identified Guiding Principles, a key consideration in the activities outlined in the proposed evaluation framework. These principles identify factors to consider when implementing national, state, and community evaluation plans and may be useful to evaluators as they seek to develop and implement their own evaluation studies. As one example, it is important to consider and develop a systematic and effective approach to communicate and provide information about the obesity-related indicators/measures to the priority population and end users/stakeholders. Consideration of this “dissemination” principle can improve reach, clarity, effectiveness, and timeliness of the results to the appropriate users/stakeholders.

In developing the Guiding Principles, the Committee reviewed existing evaluation principles, including those developed by the American Evaluation Association (2004), Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation (JCSEE, 2011), World Health Organization (WHO, 2010), prior IOM reports (IOM, 2009, 2010, 2012b), CDC (CDC, 1999), Glasgow et al. (1999), Fawcett (2002), and Green and Glasgow (2006). As a result of this review given the elements identified in the evaluation framework (see Figure 3-1), the Committee identified the following Guiding Principles (listed alphabetically for ease of presentation):

• Accuracy

• Capacity Building

• Comparability

• Context

• Coordination and Partnership

• Dissemination

• Feasibility

• Health Disparities/Equity

• Impact

• Implementation

• Parsimony

• Priority Setting

• Relevance

• Scalability

• Surveillance/Assessment

• Sustainability

• Systems-oriented

• Transparency

• Utility

• Value

Appendix C contains a detailed table of the Guiding Principles, including plain language definitions and examples of end user questions for evaluators to consider relative to each principle.

The Committee deemed it important to recognize that each evaluation is unique and that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to incorporating or utilizing the principles for every evaluation planning effort. Rather, in its deliberations related to the national, state, and community plans and its recommendations to evaluators who will implement such plans, the Committee believed it important to balance these principles based on context, end user needs, available resources, and other constraints that may appear. Thus, although important, the principles still need to be adapted to each evaluation’s specific context and needs.

Resources

Human and financial resources, and related supports, for evaluations are currently quite limited (IOM, 2012c). Although 10 to 15 percent of an intervention budget is the recommended set-aside for evaluation by funders of prevention initiatives,2 the percentage very much depends on the context. For example, allocating resources for state or national surveillance systems differs from examining the effects of a grant-funded initiative to promote physical activity and healthy nutrition. Technical support is typically needed for evaluation, including for the core tasks of obtaining end-user input; choosing indicators, measures, and designs; collecting and analyzing data; and ultimately improving the evaluation infrastructure and necessary inputs to support evaluation efforts. Because most evaluations are currently under-resourced and under-supported, the Committee’s recommendations call for expenditures for evaluation that would often result in trade-off decisions by governments and organizations (i.e., between interventions with greater reach or dose or stronger evaluations) and with astute use of existing resources and prioritization of other necessary actions implemented with short-, intermediate-, and long-term time perspectives.

_____________

2 The 10 to 15 percent set-aside for evaluation resources is a general range found in public and private grant mandates or average operation budgets (nrepp.samhsa.gov/LearningModules.aspx, accessed November 13, 2013).

Activities

Identify Indicators/Measures of Success

The Committee conducted an exhaustive review of more than 322 potential indicators to identify ways to measure progress in obesity prevention efforts. Each potential indicator was assessed to determine alignment with the Committee’s evaluation framework and the APOP goals and strategies. Furthermore, preference was given to indicators previously reported or recommended by leading national health committees that have undertaken substantial vetting processes prior to development, with priority given to Healthy People 2020 recommended indicators where available. Because Healthy People 2020 indicators do not cover all of the APOP goals and strategies, the Committee also relied on national data sources and recommendations of national advisory committees (e.g., the Community Preventive Services Task Force). When deciding on indicators for inclusion, the Committee gave preference to those that were (1) relevant and closely aligned to the APOP goals and strategies, (2) readily available from existing data sources, (3) measured on a regular basis over time (ideally every 3 years or more frequently), (4) already computed or could be easily computed based on the available data, (5) understandable to evaluators and other decision makers, and (6) associated with objectives that would galvanize action among communities and other stakeholders. Ultimately, the Committee recommended 82 indicators of progress.

The evaluation framework also notes the importance of identifying specific measures that evaluators could use to assess progress on a given indicator that is tailored to their evaluation needs. For example, a community evaluator might benefit from guidance on how to adapt a national indicator for use at the community level. Such adaptations may be necessary to fulfill an end user’s interest in seeing a longitudinal indicator of progress for a defined community. Using an example from Healthy People 2020, BMI (selfreported or independently measured) is the specific measure used to monitor the health indicator “reduce the proportion of adults who are obese” and to determine the degree to which the intended outcome—healthy weight in adults—is being met. The Committee saw a pressing need to identify or develop appropriate measures for each indicator, yet was unable to do so systematically. Instead, the Committee identified examples of measures that are tailored to the national, state, and community plans in Chapters 6, 7, and 8.

Develop Evaluation Plans and Infrastructure

From the outset, in accordance with its statement of task, the Committee aimed to develop two sets of evaluation plans that could serve as guideposts for evaluators and decision makers responsible for developing or funding evaluations to measure progress in obesity prevention. The first evaluation plan, described in detail in Chapter 6, focuses on national evaluations (which may be included in or adapted to state and regional evaluations). The second evaluation plan, described in detail in Chapters 7 and 8, focuses on the community level. The Committee’s rationale for distinguishing national-level evaluations from community-level evaluations rested on several considerations: the nature and extent of surveillance data readily available at the national/state vs. community levels; the resources required to conduct evaluations at each level; the likely end users and participants involved in planning, executing, and acting on the evaluation results; and the unique needs of varied communities that would require tailoring or customization of the evaluation.

BOX 3-1

Core Functions of an Infrastructure for Evaluation of Obesity Prevention Efforts

1. Assessment and surveillance of healthy weight prevalence to identify and solve national and community health problems related to obesity.

2. Diagnose and investigate obesity-promoting conditions and related health problems in the community.

3. Inform, educate, and empower people to use data to take action to promote physical activity, healthful nutrition, and healthy weight.

4. Use participatory methods to monitor and improve community partnerships and collaborative action to promote physical activity and healthful nutrition and to prevent obesity.

5. Evaluate the summative effects of interventions that aim to prevent obesity and promote healthy weight.

6. Monitor enforcement of laws and regulations that promote healthful eating and physical activity and that protect against obesity-promoting conditions.

7. Assure a competent workforce to implement evaluation activities at national and local levels.

8. Monitor and evaluate the effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of programs and policies to promote healthy weight.

9. Support research efforts to gain new insights and innovative approaches to monitor and evaluate efforts to prevent obesity.

10. Support efforts to disseminate new learnings and optimize wide adoption and implementation of the most efficient and effective evaluation methods.

SOURCE: Adapted from CDC, 2010.

Evaluation activities would benefit from an infrastructure to make this work easier and more effective. Consistent with the CDC National Public Health Performance Standards Program,3 core functions and essential services for an evaluation infrastructure for obesity prevention might include capabilities to monitor, diagnose, and investigate (which in this report encompasses assessment and surveillance of the needs and monitoring of the interventions to address them); inform and educate; mobilize; develop policies and plans; enforce; link; assure; evaluate; and research (see Box 3-1 for details).

_____________

3 See http://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp (accessed November 11, 2013).

Enhance Resources for Training, Technical Assistance, and Dissemination of Evaluation Methods

Additional resources and supports for their widespread use are needed to help prepare the workforce for collecting and using data to assess progress in obesity prevention efforts. These include, for example, enhanced curricula in methods of assessment/surveillance and community-based participatory monitoring/ summative evaluation. To reflect the diversity of those individuals who conduct and use evaluations, curriculum modules on these topics would be offered through multiple relevant disciplines including public health, public administration, education, community nursing, and behavioral and social sciences.

Field-tested protocols for monitoring/summative evaluation, such as CDC’s framework for program evaluation in public health (CDC, 1999), should be more widely available. Chapter 8 presents an adaptation of this framework for community monitoring/summative evaluation of obesity prevention efforts.

Guiding principles and standards for evaluators, such as those of the American Evaluation Association (2004), also need to be promulgated.

Web-based supports can help to assure free access to practical guidance for developing and implementing an evaluation plan; note a further case for this in Chapter 7 and included as a recommended action to improve access to and dissemination of evaluation data in Chapter 10 (Recommendation 4). For example, the open-source Community Tool Box4 offers more than 30 sections on evaluation efforts, each with how-to steps, examples, and PowerPoint presentations that can be adapted for training. These and other Web-based supports could be combined in a “basket of tools” for community assessment/surveillance and monitoring/summative evaluation—free and accessible through the Internet, mobile phones, and other means to reach a diverse audience with just-in-time supports for this work.

Clearinghouses for evaluation measures, such as the measures registry of the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research (NCCOR, 2013), offer promise in increasing evaluation capacity in the field. Media communications and case examples of how evaluation activities were used to target and improve obesity prevention efforts can help to enhance their perceived value and widespread use.

In addition, knowledge brokers (Ward et al., 2009)—those whose specialized expertise in assessment, monitoring, surveillance, and summative evaluation, communications, and other critical practices in the field—can bridge the gap between what is known about evaluation-related activities and how activities are implemented. Research, training, and consulting groups can serve as critical intermediary organizations to help support state and community efforts to create timely information and use it to inform obesity prevention efforts.

Outputs

To help assure outputs related to these activities, the Committee identified key tasks that governmental and other organizations need to engage in to support the assessment, development of consensus on, and more uniform application of a set of core indicators and common measures (see Chapter 4). The Committee also provided recommendations and guidance on methods and protocols for evaluation (see Chapters 5 through 9) and associated supports for the implementation and enhanced data use (see Chapter 10). The following presents an overview of recommended outputs and why they are important to the success of this framework to inform and improve obesity prevention efforts.

_____________

4 Available online at http://ctb.ku.edu/en/default.aspx (accessed November 11, 2013).

Core Indicators and Common Measures

As part of the National Evaluation Plan proposed in Chapter 6 and using the indicator list identified in Chapter 4, the Committee advises on the need to identify a core set of indicators to evaluate progress at the national level in implementing the APOP strategies. As described in a prior IOM report, four levels of indicators can be used to assess progress: overarching (incidence and prevalence of overweight and obesity), primary (energy expenditure/intake), process (related to policy and environmental strategies), and foundational (disparities, advocacy, coalition building) (IOM, 2012a). Core indicators are intended to help to standardize the target used to assess progress on obesity prevention across the nation, states, and localities. Obesity prevention efforts can be enhanced by the development of core indicators that reflect the continuum of outcomes relevant to obesity prevention, including environmental changes, behaviors, and weight/obesity. The Committee recognized a need in the field to identify or develop related quantifiable measures for each core indicator.

The Committee found that evaluation users have numerous individual behavioral indicators, but they need guidance on a core set of environmental change outcomes that influence access and availability of healthful food, beverages, and activity. Guidance for evaluators or evaluation users is particularly needed for

• identifying, prioritizing, or selecting common quantifiable measures sensitive to goals/objectives;

• identifying core types and attributes of environmental changes to be measured;

• documenting and analyzing the contribution of multiple changes in programs and policies for collective impact;

• accounting for analysis at the level of communities and broader systems;

• gauging the type of infrastructure necessary to support monitoring and summative evaluation activities;

• assessing changes in the level of investments that reflect the engagement in and support for obesity prevention activities;

• leveraging networks, identifying leaders, and enabling continuous learning to advance best practices in obesity prevention; and

• identifying and promoting the contributions that institutions, workplaces, and health care can make to enhance physical activity, nutrition, and healthy weight.

Assessing environmental changes can help evaluation users to identify progress with conditions that influence individual and family choices about diet and physical activity.

Evaluation users need guidance in choosing a core set of indicators and related measures that assess changes in key behaviors of individuals or populations that affect their weight and enhance health in their settings. These behaviors include diet, physical activity, sedentary behavior, and other obesity-related behaviors and social norms that affect energy balance and risk for obesity. Finally, a core set of indicators and related measures that assess changes in weight and related obesity outcomes (e.g., incidence and prevalence of obesity) will inform and improve obesity prevention efforts. Assessing changes to this type of outcome, whether by individuals or populations, can help to detect progress in reducing risk of developing specific health conditions. These important outputs are included in the evaluation plans recommended in the report.

Recommendations and Guidance

Throughout the report, the Committee offers recommendations and guidance on priorities for the most appropriate methods and protocols for evaluating obesity prevention efforts (Chapters 4, indicators; Chapter 5, methods and tools for evaluating progress in health equity; Chapter 6, protocols and methods for national efforts; Chapters 7 and 8, protocols and methods for community efforts). These can serve the field by setting priorities for methodological development and strengthening of available data sources. These recommendations also offer guidance on enabling and facilitating ongoing assessment and research at all levels (community, state, national), for varied populations, and in multiple settings and diverse contexts. Consistency in such measurement across settings and over time, with potential for record linkages, would not only serve the needs of communities for evaluation of their own efforts, but also allow for comparisons between and among jurisdictions, institutions, and populations, to identify the relative effectiveness of their respective policies and programs. Consistency, however, must give way to adapted measures in some settings, populations, and circumstances. Guidance is needed for assuring consistency of appropriate methods of assessments and surveillance; appropriate adaptations for monitoring and summative evaluations at the community and systems levels; and measurement of health equity and the conditions that produce it. Variations in context require adaptation to fit the situations. Decision trees could help to guide choices in implementing protocols for evaluation activities in the face of community resource limitations and differences in context.

Effective assessment and surveillance is necessary for the successful targeting and management of obesity prevention efforts. Choosing the appropriate assessment method depends on the outcome of interest. Factors to consider include what information is needed (e.g., is the information relevant to a policy choice), how often does it need to be assessed, and what duration between measurements is necessary to see changes (e.g., short term, intermediate term, long term). In addition, communities have different assets and resources, so each locality must be able to monitor and evaluate obesity prevention activities within those limitations and use the resultant information to inform the broader field. Community-level evaluation users need protocols to help to guide evaluation, to make it practical for low-resource environments and to inform the broader effort across the nation. Additionally, consistent with systems science, evaluations need to consider the complicated relationships among the outcomes of interest, the diverse set of factors at multiple ecological levels that can influence the outcomes, and the benefits and harms beyond obesity and health that programs and policies might produce (IOM, 2012b).

Although a systems approach is in the early stages of implementation, evaluation users need guidance for evaluation and tracking of possible synergies and feedback among obesity prevention activities across multiple sectors and levels (see Chapters 9 and 10). Because of the complexity of identifying, measuring, and monitoring the continuum of outcomes relevant to obesity prevention, it is especially challenging to reach a consensus about assessing progress in reducing health disparities among socially disadvantaged groups. Interactions among social and environmental determinants of health need specific attention to better track and accelerate progress in promoting health equity (see Chapters 5 and 9). Similarly, evaluation users need specific guidance to monitor and evaluate the setting or context-specific conditions of obesity prevention activities. Improved documentation and characterization of broader environmental conditions (e.g., political, social, organizational) in which the activity is being implemented can help to inform practice in other settings. Finally, general evaluation criteria and decision trees would pro-

vide a common resource for practitioners and decision makers attempting to collect and use assessment, monitoring, or surveillance information in their contexts. These criteria can also provide a way to assess the quality and impact of the outcomes achieved in obesity prevention efforts. Evaluation may appear difficult to grasp and plan for when initiating, developing, and implementing obesity prevention activities; accordingly, this guidance can provide support for the systematic collection and effective use of evaluation information as diagnostic data during the initial assessment stages of planning, as quality control data during the monitoring of activities during implementation, and ultimately as baseline data for summative evaluation (Green and Kreuter, 2005).

Support for Implementation

Evaluations are complex and require a prepared workforce to be responsive to the many and varied needs and interests of end users (see Chapter 2 for more details). Participatory evaluation—engaging end users in developing the evaluation and all phases of its implementation and related sense making—is an important way to support implementation and effective use of evaluation information. Recommended supports for implementation include selecting individuals with related experience, training in core competencies of evaluation (e.g., developing a logic model and questions of interest to stakeholders, implementing assessments, measuring change), and coaching during implementation of the evaluation plan (e.g., in adapting core competencies to the context, such as identifying evaluation questions and implementing methods). In addition, performance feedback can help to assure implementation consistent with the agreed-upon plan for assessment or evaluation (Fixsen et al., 2009). Well-supported evaluations can provide end users with information about specific conditions that make a program’s implementation and impact more successful and can inform decisions for adjustments in implementation for a particular situation or other contexts.

Outcomes

Inputs, activities, and outputs as described above all have their ultimate lines of presumed causal relationship to specific outcomes. Each is a support for the combined convergence of efforts to achieve obesity prevention. Parallel with these desired behavioral, environmental, and health (weight- and obesity-related) outcomes are improved intervention capacities in the short-term, increased evaluation activities in the intermediate-term, and enhanced data use in the long-term. Combined, these intended outcomes represent enhanced capacity for evaluation activities needed to understand and improve progress in preventing obesity and achieving population health and health equity.

Short-Term: Improved Capacity and Infrastructure of Evaluation Activities

Evaluation users need resources and infrastructure to build and maintain capacity for successful evaluations. End-user needs must be clearly aligned with evaluation methods, key measures, and resources for implementation. Therefore, the Committee calls attention to several key conditions to assure successful evaluation activities:

Awareness of value and uses of evaluation activities. To ensure continued support and sustained commitment to obesity prevention evaluation efforts, broad awareness of the value of evaluation is paramount.

Value of such efforts is defined here as the ability of evaluation efforts to show the benefits minus the costs (and harms) to obesity prevention initiatives (IOM, 2012b).

Adoption of recommended core indicators. It will be nearly impossible to show the value of obesity prevention efforts without collecting the right common measures. A critical short-term outcome is the integration of recommended core indicators with related measures into data collection tools and activities.

Useful data (community, trends, comparable). To optimize the relevance of evaluation efforts, the findings need to be meaningful to the intended audiences. End users note important attributes of useful evaluations, including the capacity to show change over time in local jurisdictions and comparability to other comparison communities, places, or groups.

Engagement of end users. The early involvement and continued engagement of those who have a vested interest in the evaluation are paramount. Benefits include the assurance of a collaborative approach, likelihood that the results will be used, continued support for programs, and acceptance of the evaluation results as credible (CDC, 2011).

Resources devoted to evaluation activities. Resources are not limited to money. They include time, energy, people, and innovative approaches to evaluation. They also include support systems for assuring the fidelity or appropriate adaptation of evaluation procedures and protocols to make them fit or to incorporate the knowledge and experience of practitioners in the community settings (Gaglio and Glasgow, 2012; Green and Glasgow, 2006; IOM, 2010; Kottke et al., 2012).

Use of Web-based supports for implementation. Internet-based resources can provide widespread access to training materials and supports for implementing evaluation activities. For instance, the Healthy People 2020 website5 features an “Implement” tab with links to resources to “Track” progress on objectives including links to the Community Tool Box and other Web-based resources. In participatory evaluation contexts, Internet-based platforms have been used to support data collection, graphic feedback, systematic reflection on accomplishments, and adjustments in practice (Fawcett et al., 2003). Internet-based tools can make implementation of updated evaluation methods and protocols easier and more effective.

Intermediate-Term: Increased Evaluation Activities

Intermediate-term outcomes relate to the widespread adoption and effective use of evaluation to understand and support obesity prevention initiatives. Key aspects include the following:

System-wide use of evidence-based interventions. Widespread use of what works in obesity prevention requires a market for effective prevention strategies. Broad adoption, translation, and application of evidence-based strategies are essential to accelerating progress in obesity prevention. Evaluation can assist by extending evidence of the generality of programs and policies shown to be effective elsewhere to new contexts and with new groups, including those affected by health disparities (Green and Glasgow, 2006).

_____________

5 See http://www.healthypeople.gov (accessed November 11, 2013).

Use of effective prevention interventions can help to reduce health care spending, reduce illness burden, and increase longevity (Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2011).6

Timely and useful evaluations. To optimize the relevance of evaluation efforts, the data need to be presented in as meaningful and timely a manner as possible to the intended audiences (Brownson et al., 2006). Regardless of whether the audience is national, state, or community level, the data need to be presented in a way that is appropriate, useful, and applicable to the interests of end users (Pronk, 2012).

Workforce education for evaluation activities. The ability to monitor and evaluate progress is a required capability of the workforce in obesity prevention. This capability would apply to evaluation professionals and professionals working in the multiple sectors, such as government, health, and education who make up the broad obesity-prevention workforce. There is a need for both generalized and specialized knowledge in evaluation methods, perhaps as taught in undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education courses in multiple disciplines including public health, public administration, education, and behavioral and social sciences.

Periodic assessment and surveillance of obesity-related behaviors and outcomes. Government and organizations need to support the development, maintenance, and proper use of systems for obesity-related surveillance. Although national surveillance is mainly adequate, there are numerous gaps in timing and coverage of indicators and populations as attention moves from the national to state to community levels. Public health agencies—at federal, state, and community levels—need to take a lead role in developing these systems to assure adequate tracking of rates of risk behaviors and obesity and its determinants.

Monitoring of changes in policies, programs, built environment, and systems. Evaluation of progress in obesity prevention requires careful monitoring of the environment—especially those community programs, policies, features of the built environment, and aspects of broader systems that can affect physical activity and healthful nutrition. For example, it is possible to reliably document instances of community/systems change—new or modified programs, policies, and practices—that define the unfolding of comprehensive community interventions in different sectors (Fawcett et al., 1995, 2001). A monitoring infrastructure—at community and system levels—could help to document and detect changes in the environment that might accelerate (or impede) progress in obesity prevention efforts at various levels (IOM, 2012b).

Monitoring of implementation and intensity of community programs/policies. To assess the intensity of community efforts to prevent obesity, evaluators can systematically document community programs and policies and characterize key attributes that might affect their collective impact on population health and health equity (Fawcett et al., 2010). Evaluation researchers have documented and characterized community programs and policies of chronic disease prevention efforts by attributes, such as strength of change strategy and duration, thought to be associated with collective impact in groups experiencing health disparities (Cheadle et al., 2010, 2013; Collie-Akers et al., 2007; Fawcett et al., 2013). Progress in obesity prevention in a given community is likely to be associated with both the amount and kind of

_____________

6 See http://www.thecommunityguide.org (accessed November 11, 2013).

environmental changes, including their strength, duration, reach, and sustainability (Glasgow et al., 1999; Pronk, 2003).

Long-Term: Enhanced Data Use

Long-term outcomes of evaluation capacity include data-driven adjustments and improvements to programs and policies over time. Enhancements in the use of data also include systematic reflection on knowledge that has been generated as a result of the short- and intermediate-term evaluations:

Wider adoption and more effective use of evaluation-related data at national, state, and community levels. An intended outcome of evaluation capacity is widespread adoption and effective use of data by decision makers in multiple settings and at multiple levels. Data on progress need to be readily accessible so their utility in quality improvement and sustainability of interventions is optimal (Ottoson and Hawe, 2009; Ottoson and Wilson, 2003). The effectiveness of the use of these data will be reflected in innovations that emerge from ongoing use of accessible data on progress (similar to examples in crime mapping,7 etc.) (Crime Mapping, 2012). Similarly, a surveillance infrastructure can assure monitoring of impact variables to help to detect improved (and worsening) behaviors and environments related to obesity prevention and improved population health.

Knowledge utilization to understand and improve obesity prevention efforts. Once data on environmental change and outcomes are generated, they are available for systematic reflection and use in making adjustments. For example, an empirical study of data uses by decision makers in a prevention effort showed that data were more frequently used for reviewing progress of the initiative, communicating successes or needed improvement to staff, and communicating accomplishments to end users (Collie-Akers et al., 2010). Ready availability of data on progress to end users can enhance understanding of and adjustments to obesity prevention efforts.

Impacts

The impacts section of the framework outlines the population-level changes and improvements that can result from widespread implementation of evidence-based interventions to prevent obesity. These represent the ultimate goals, objectives, and cumulative impact—including benefits and harms—of these strategies (IOM, 2012b). The guidance from the previous sections of the framework are intended to support and enable assessment, monitoring, surveillance, and summative evaluation that detect merit, assure accountability, and promote quality improvement of obesity prevention efforts.

Intended impact is mirrored in the process of collaborative public health action in which activities of multi-sector/multi-level partnerships lead to improved physical and social environments, behaviors, and population-level outcomes (Collie-Akers and Fawcett, 2008; IOM, 2003). These impact variables have a reciprocal relationship, in which changes in one impact or sector can influence and change the other impacts or sectors. For example, providing sidewalks and adequate crossing guards for schools (improved physical environment) can lead to increased physical activity because more children can walk to school (improved behaviors), which was brought about by engagement of different sectors of the community

_____________

7 “Crime mapping” provides crime data visually on a map to help to analyze crime patterns.

(systems-level changes). If more children begin walking to school, then this change could prompt further collaborative action among schools, county government, and community leaders to build more and better sidewalks and bike paths that connect home and school.

Changes in environments and systems are intended to result in changes in behaviors leading to increased energy expenditure (through increased physical activity) and decreased energy intake (through dietary changes); these changes in turn lead to decreased incidence and prevalence of overweight and/or obesity.8 With a population-level reduction in overweight and obesity, morbidity and mortality levels from obesity-related conditions will also decrease, leading to improved population health.

Multi-Sector/Multi-Level Partnerships

Collaborative action to promote healthful living and prevent obesity often takes the form of multi-sector partnerships or coalitions that form within and across various sectors (see Chapters 9 and 10). How much and in what forms such partnerships and coalitions achieve or enhance health outcomes remains a subject of theoretical and empirical debate (Butterfoss et al., 2008; Kreuter et al., 1990). But practical experience suggests ways in which they facilitate community-level action and systems change. For example, as described above, schools and county governments can form partnerships to promote active transport to schools that benefit each partner in different ways. Processes that influence the amount and kind of system change brought about by collaborative partnerships include analyzing information about the problem, developing strategic and action plans, providing technical support for implementing effective strategies, documenting progress, using feedback, and making outcomes matter (Fawcett et al., 2010).

Improved Physical and Social Environments

As described in Chapter 1, the Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention report (IOM, 2012a) focused on improving physical and social environments to make better food and activity choices the default, or the “opt out” choices (Novak and Brownell, 2012). Physical and social environments can have significant influence on food and activity patterns. Presently these environments promote unhealthful rather than healthful choices, and the conditions and effects of these environments are significantly worse for socially disadvantaged groups (IOM, 2012a).

The past few years have seen significant progress in the development of tools and instruments for assessing health-promoting (or -inhibiting) aspects of the environment as related to obesity (NCCOR, 2013; Ottoson et al., 2009; Sallis and Glanz, 2009). As new methods are developed and used, baseline standards can be set to measure progress. With increasing implementation of evidence-based strategies, it is necessary to fully document the fidelity of implementation and efficacy of interventions, including measurement of changes in environmental factors.

Improved Behaviors and Social Norms

Changes in the physical and social environments, as well as programmatic and educational efforts, can lead to improved dietary intake and physical activity. Dietary intake and physical activity can be mea-

_____________

8 There can also be unintended consequences. For example, harms associated with changes in social norms may increase social disapproval and discrimination against those who are overweight.

sured using a variety of methods, which range from self-administered survey-type questions for epidemiologic applications to more sophisticated physical measures as described below.

In addition to measuring the physical environment, documenting the social environment by measuring changes in norms, self-efficacy, beliefs, outcome expectations, and other psychosocial factors can help to identify influences on healthful eating and activity behaviors (Flay et al., 2009). Recent studies have found that social influences are associated with obesity, as demonstrated through social networks, in which group beliefs and normative behaviors can affect the behaviors of peers (Hammond, 2010). Norms allow for social constraints and/or permissions to occur, and, as a result, they have the potential to influence the behavior of individuals of the group. Such changes in social norms or other related psychosocial factors can be difficult to measure across a population, because many of the constructs are specific to a particular program, behavior, and/or environment. Development of standard indicators of changes in social norms could lead to better understanding of how they may influence population-level behavior.

Increased Energy Expenditure and Decreased Energy Intake

As environments and behaviors change through multi-sector and multi-level interventions, a logical conclusion is that increased energy expenditure and decreased energy intake will result. Current methods of quantifying energy expenditure in individuals include self-reported surveys, direct observations, and of motion-capturing devices such as accelerometers and calorimetry (Levine, 2005). Energy intake can be measured using standard techniques such as doubly labeled water method9 or newer tools such as computer imaging (Hu, 2008). Limitations in the use of self-reported techniques for measuring energy intake (i.e., 24-hour dietary recalls) have been identified (Schoeller et al., 2013), and therefore evaluations done in low-resource contexts should consider alternate methods.

Reduced Overweight/Obesity

The primary physiologic measure of impact noted in this framework (see Figure 3-1) is reduction in overweight and obesity. At the most basic level, overweight and obesity result from an imbalance between energy expenditure and energy intake. The factors that influence energy expenditure and energy intake are diverse and have varying influence in different contexts. Assessing overweight and obesity is relatively straightforward, and population-level progress can be measured through both incidence—new cases—and prevalence or existing cases (see Chapter 4 for suggested list of indicators). For children, who are growing and developing rapidly, measurement of changing overweight/obesity prevalence is the best population indicator of impact (although a direct measure of incidence would be preferable). For adults, the measurement of prevalence of overweight and obesity can also be a practical approach to assessing progress in obesity-related initiatives. Yet, as described in Chapter 1 overweight/obesity may not be the most sensitive measure because excess weight has been shown to be extremely intractable in adults, and weight loss is not easily maintained over time. Where feasible to collect, the appearance in a population of new cases of overweight and obesity in adults (i.e., changes in incidence) may be more responsive to recent changes in the environment and associated changes in behaviors.

_____________

9 The “doubly labeled water method” measures energy expenditure, body composition, and water flux in individuals.

Ultimate Intended Impact

The final intended impact of monitoring progress in obesity prevention is improved population health or well-being and health equity, two of the primary overarching objectives of Healthy People 2020 (HHS, 2010b). These impact variables are logical consequences of decreased incidence and prevalence of overweight/obesity and associated obesity-related morbidity and mortality. Decreases in obesity-related medical chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, and their costs, will lead to a healthier nation and economy. In addition, the mental health effects and bullying that are associated with excess body weight and poor body image may be attenuated, leading to further medical cost savings and increased well-being. Insofar as overweight/obesity and related conditions disproportionately affect low-income and socially disadvantaged populations, a significant impact of implementing recommended strategies for obesity prevention would be improved health equity. The science and practice of assuring health equity would benefit from improved understanding of how these hypothesized mechanisms of social determinants—differential exposures, vulnerabilities, and consequences—work to affect disparities in weight and health outcomes.

REFERENCES

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2008. The Bright Futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

American Evaluation Association. 2004. Guiding principles for evaluators. http://www.eval.org/Publications/GuidingPrinciples.asp (accessed January 13, 2013).

Brownson, R. C., C. Royer, R. Ewing, and T. D. McBride. 2006. Researchers and policymakers: Travelers in parallel universes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 30(2):164-172.

Butterfoss, F. D., M. C. Kegler, and V. T. Francisco. 2008. Mobilizing organizations for health promotion: Theories of organizational change. In Health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. 4th ed, edited by K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer and K. Viswanath. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 335-362.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1999. Framework for program evaluation in public health. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 48(RR11):1-40.

CDC. 2010. 10 essential public health services. http://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialservices.html (accessed March 20, 2013).

CDC. 2011. Developing an effective evaluation plan. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity.

Cheadle, A., S. E. Samuels, S. Rauzon, S. C. Yoshida, P. M. Schwartz, M. Boyle, W. L. Beery, L. Craypo, and L. Solomon. 2010. Approaches to measuring the extent and impact of environmental change in three California community-level obesity prevention initiatives. American Journal of Public Health 100(11):2129-2136.

Cheadle, A., P. M. Schwartz, S. Rauzon, E. Bourcier, S. Senter, B. Spring, and W. L. Beery. 2013. Using the concept of “population dose” in planning and evaluating community-level obesity prevention activities. American Journal of Evaluation 34(1):71-84.

Collie-Akers, V., and S. B. Fawcett. 2008. Preventing childhood obesity through collaborative public health action in communities. In Handbook of child and adolescent obesity, edited by E. Jelalian and R. G. Steele. New York: Springer Science. Pp. 351-368.

Collie-Akers, V. L., S. B. Fawcett, J. A. Schultz, V. Carson, J. Cyprus, and J. E. Pierle. 2007. Analyzing a community-based coalition’s efforts to reduce health disparities and the risk for chronic disease in Kansas City, Missouri. Preventing Chronic Disease 4(3):A66.

Collie-Akers, V. L., J. Watson-Thompson, J. A. Schultz, and S. B. Fawcett. 2010. A case study of use of data for participatory evaluation within a statewide system to prevent substance abuse. Health Promotion & Practice 11(6):852-858.

Crime Mapping. 2012. Building safer communities. http://www.crimemapping.com (accessed November 19, 2012).

Fawcett, S. B. 2002. Evaluating comprehensive community initiatives: A bill of rights and responsibilities. In Improving population health: The California Wellness Foundation’s health improvement initiative, edited by S. Isaacs. San Francisco, CA: Social Policy Press. Pp. 229-233.

Fawcett, S. B., T. Sterling, A. L. Paine-Andrews, K. J. Harris, V. T. Francisco, K. P. Richter, R. K. Lewis, and T. Schmid. 1995. Evaluating community efforts to prevent cardiovascular diseases. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Fawcett, S. B., A. Paine-Andrews, V. T. Francisco, J. A. Schultz, K. P. Richter, J. Berkley-Patton, J. L. Fisher, R. K. Lewis, C. M. Lopez, S. Russos, E. L. Williams, K. J. Harris, and P. Evensen. 2001. Evaluating community initiatives for health and development. In Evaluation in health promotion: Principles and perspectives, edited by I. Rootman, M. Goodstadt, B. Hyndman, D. V. McQueen, L. Potvin, J. Springett and E. Ziglio. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization. Pp. 341-370.

Fawcett, S. B., J. A. Schultz, V. L. Carson, V. A. Renault, and V. T. Francisco. 2003. Using internet-based tools to build capacity for community-based participatory research and other efforts to promote community health and development. In Community-based participatory research for health, edited by M. Minkler and N. Wallerstein. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 155-178.

Fawcett, S. B., J. Schultz, J. Watson-Thompson, M. Fox, and R. Bremby. 2010. Building multisectoral partnerships for population health and health equity. Preventing Chronic Disease 7(6):A118.

Fawcett, S. B., V. Collie-Akers, J. A. Schultz, and P. Cupertino. 2013. Community-based participatory research within the Latino Health for All Coalition. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community 41(3):142-154.

Fixsen, D., K. Blase, S. Naoom, and F. Wallace. 2009. Core implementation components. Research on Social Work Practice 19:531-540.

Flay, B. R., F. J. Snyder, and J. Petraitis. 2009. The theory of triadic influence. In Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. 2nd ed, edited by R. J. DiClemente, M. C. Kegler, and A. Crosby. New York: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 451-510.

Gaglio, B., and R. Glasgow. 2012. Evaluation approaches for dissemination and implementation research. In Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice, edited by R. C. Brownson, G. A. Colditz, and E. K. Proctor. New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 327-356.

Glasgow, R. E., T. M. Vogt, and S. M. Boles. 1999. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health 89(9):1322-1327.

Green, L. W., and R. E. Glasgow. 2006. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: Issues in external validation and translation methodology. Evaluation and the Health Professions 29(1):126-153.

Green, L. W., and M. W. Kreuter. 2005. Health program planning: An educational and ecological approach. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hammond, R. A. 2010. Social influence and obesity. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity 17(5):467-471.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2008. 2008 Physical activity guidelines for Americans. 7th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

HHS. 2010a. Dietary guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

HHS. 2010b. Healthy People 2020. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx (accessed January 31, 2013).

Hu, F. B. 2008. Dietary assessment methods. In Obesity epidemiology, edited by F. B. Hu. New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 84-118.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. The future of the public’s health in the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2009. Local government actions to prevent childhood obesity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2010. Bridging the evidence gap in obesity prevention: A framework to inform decision making. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012a. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: Solving the weight of the nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012b. An integrated framework for assessing the value of community-based prevention. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012c. Evaluating progress of obesity prevention efforts: What does the field need to know? Paper read at Public Session of the Committee on Evaluating Progress of Obesity Prevention Efforts, October 12, 2012, Washington, DC.

IOM. 2012d. Measuring progress in obesity prevention: Workshop report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

JCSEE (Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation). 2011. The program evaluation standards: A guide for evaluators and evaluation users. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kettel Khan, L., K. Sobush, D. Keener, K. Goodman, A. Lowry, J. Kakietek, and S. Zaro. 2009. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 58(RR-7):1-26.

Kreuter, M. W., N. Lezin, and L. Young. 1990. Evaluating community-based collaborative mechanisms: Implications for practitioners. Health Promotion and Practice 1(1):49-63.

Kottke, T. E., N. P. Pronk, and G. J. Isham. 2012. The simple health system rules that create value. Preventing Chronic Disease 9:E49.

Levine, J. A. 2005. Measurement of energy expenditure. Public Health Nutrition 8(7A):1123-1132.

NCCOR (National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research). 2013. NCCOR Measures Registry. http://nccor.org/projects/measures/index.php (accessed June 15, 2012).

Novak, N. L., and K. D. Brownell. 2012. Role of policy and government in the obesity epidemic. Circulation 126(19):2345-2352.

NPC (National Prevention Council). 2011. National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Ottoson, J. M., and P. Hawe, eds. 2009. Knowledge utilization, diffusion, implementation, transfer, and translation: Implications for evaluation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Ottoson, J. M., and D. H. Wilson. 2003. Did they use it? Beyond the collection of surveillance information. In Global behavioral risk factor surveillance, edited by D. McQueen and P. Puska. New York: Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers. Pp. 119-131.

Ottoson, J. M., L. W. Green, W. L. Beery, S. K. Senter, C. L. Cahill, D. C. Pearson, H. P. Greenwald, R. Hamre, and L. Leviton. 2009. Policy-contribution assessment and field-building analysis of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Active Living Research Program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36(2 Suppl):S34-S43.

Pronk, N. P. 2003. Designing and evaluating health promotion programs: Simple rules for a complex issue. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 11(3):149-157.

Pronk, N. P. 2012. The power of context: Moving from information and knowledge to practical wisdom for improving physical activity and dietary behaviors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 42(1):103-104.

Rogers, E. M. 2003. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: The Free Press.

Sallis, J. F., and K. Glanz. 2009. Physical activity and food environments: Solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Quarterly 87(1):123-154.

Schoeller, D. A., D. Thomas, E. Archer, S. B. Heymsfield, S. N. Blair, M. I. Goran, J. O. Hill, R. L. Atkinson, B. E. Corkey, J. Foreyt, N. V. Dhurandhar, J. G. Kral, K. D. Hall, B. C. Hansen, B. L. Heitmann, E. Ravussin, and D. B. Allison. 2013. Self-report-based estimates of energy intake offer an inadequate basis for scientific conclusions. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 97(6):1413-1415.

Tabak, R. G., E. C. Khoong, D. A. Chambers, and R. C. Brownson. 2012. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43(3):337-350.

Task Force on Community Preventive Services. 2005. The Guide to Community Preventive Services: What works to promote health?, edited by S. Zaza, P. A. Briss, and K. W. Harris. New York: Oxford University Press.

Task Force on Community Preventive Services. 2011. First annual report to Congress and to agencies related to the work of the task force. Atlanta, GA: The Community Guide.

Truman, B. I., C. K. Smith-Akin, A. R. Hinman, K. M. Gebbie, R. Brownson, L. F. Novick, R. S. Lawrence, M. Pappaioanou, J. Fielding, C. A. Evans, Jr., F. A. Guerra, M. Vogel-Taylor, C. S. Mahan, M. Fullilove, and S. Zaza. 2000. Developing the Guide to Community Preventive Services—overview and rationale. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 18(1 Suppl):18-26.

Ward, V. L., A. O. House, and S. Hamer. 2009. Knowledge brokering: Exploring the process of transferring knowledge into action. BMC Health Services Research 9:12.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. Population-based prevention strategies for childhood obesity. Report of a WHO forum and technical meeting, Geneva, 15-17 December 2009. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.