The Economic, Cultural, and Social Landscape

Important Points Made by the Speakers

- The effects of the Great Recession that started in 2008 have caused a major loss of opportunities for young adults. (Shierholz)

- Adolescents and young adults ultimately will live in a plurality with a racial and ethnic makeup closer to that of their own cohort. (Rivas-Drake)

- Virtually constant connectivity, combined with the ability to identify one’s location in real time and rapidly evolving social media, make it possible for young adults to curate and manage their life on the go. (Lenhart)

Young adults today seem to confront a different economic, cultural, and social landscape than did earlier cohorts. They are coming of age at a time of reduced job opportunities, increasing diversity, and rapid technological change. Three speakers discussed these changes and their effects on the lives of young adults.

Young workers continue to face a difficult labor market as they make the transition from school to the workforce, said Heidi Shierholz, a labor

market economist with the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, DC. At the time of the workshop, the overall unemployment rate was about 7.5 percent, down from a peak of 10 percent at the end of 2009 (BLS, 2013). However, part of this improvement has occurred because an estimated 4 million people have dropped out of or have never entered the labor force because of weak job opportunities, said Shierholz. If these people were included in the jobless statistics, the unemployment rate would be 9.7 percent (Shierholz, 2013). (As pointed out during the discussion period, the high incarceration rate in the United States contributes to weak labor market outcomes of some groups, given the difficulty people with criminal records have finding jobs.) Furthermore, about 30 percent of those 4 million missing workers are under the age of 25, Shierholz added.

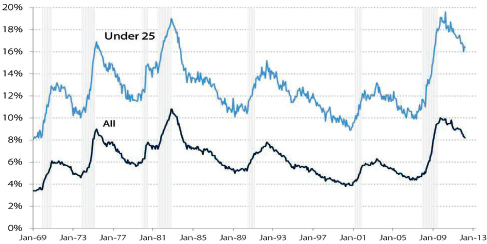

The unemployment rate for those under the age of 25 has always been about twice as high as the overall rate (see Figure 3-1). Furthermore, the “safety net of federal and state assistance often does not cover young workers due to eligibility requirements such as significant prior work experience” (Shierholz et al., 2012, p. 2). (For example, unemployment insurance requires that a person have a significant work history.) As a result, many young workers who cannot find jobs have turned to their families for assistance, which may themselves have been hit hard by the recession.

Shierholz discussed the labor market prospects of three particular groups, chosen partly because data are available on those groups: Ameri-

FIGURE 3-1 Unemployment rate for young workers always about twice as high as overall.

NOTE: Shaded areas denote recessions. Data are not seasonally adjusted.

SOURCE: Shierholz, 2013 (author’s analysis of Current Population Survey public data series).

cans ages 19-24 without a high school degree and not enrolled in school; high school graduates ages 17-20 who are not enrolled in college; and college graduates ages 21-24 who are not enrolled in graduate school.

The unemployment rates for all three of these groups vary markedly with race and ethnicity. For example, the unemployment rate is more than 50 percent for black workers ages 19-24 without a high school diploma, nearly twice that of the white rate (Shierholz et al., 2013). Moreover, said Shierholz, the unemployment rates for blacks and Hispanics have improved less in the past few years than they have for whites.

Young workers with more education have lower unemployment rates than those with less education. But the rates for all groups are significantly elevated compared to the rates before the Great Recession. “Even though young workers with higher levels of education are better off, they are still much worse off than their older brothers and sisters who graduated before the Great Recession hit,” said Shierholz.

Many young workers are not unemployed but are “underemployed,” which includes people who are unemployed, jobless but discouraged and no longer seeking work, or working part-time but looking for full-time jobs. Again, this rate rose precipitously during the Great Recession and has come down very slowly. Furthermore, this rate does not include people who are working at a job that does not use their skills or experience—such as the college graduate working as a coffee shop barista. Many of these people have been hired for jobs that could be filled by someone without a college degree, which further reduces the job prospects of those with less education.

Some young workers may have responded to the Great Recession by staying in or returning to school, which could help their job prospects in the long run. But Shierholz pointed out that the percentage of young high school graduates enrolled in a college or university has not changed in recent years from the long-term increasing trend. Although some students may have been able to shelter in school from the bad labor market, others may not have been able to enter college because of a lack of jobs or adequate financial aid to support their education (Shierholz et al., 2012). The net result, said Shierholz, is “a huge loss of opportunities for this young generation that will follow them for the rest of their lives.”

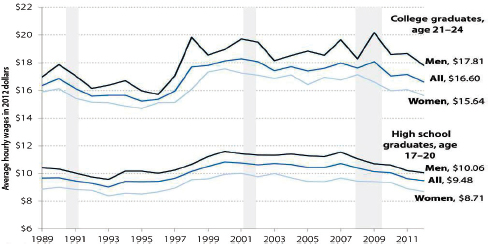

For those young high school and college graduates fortunate enough to get jobs, wages have been declining in recent years (see Figure 3-2). Not since the tight labor markets of the late 1990s have wages for this group improved substantially (Shierholz, 2013). “Young workers’ outcomes really depend on the state of the labor market when they enter,” Shierholz observed. “If they are lucky enough to enter when the labor market is strong, they do much better than if they have the misfortune, through no fault of their own, to enter at a time when the labor market is weak.”

The share of young adults with employer-provided health insurance

FIGURE 3-2 The real average hourly wages of young high school and college graduates have been steady or falling for more than a decade.

NOTE: Data are for college graduates ages 21-24 and high school graduates ages 17-20 who are not enrolled in further schooling. Shaded areas denote recessions.

SOURCE: Shierholz, 2013 (author’s analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotations Group microdata).

has also declined, said Shierholz. In 1989, 60 percent of college graduates ages 21-24 had employer-provided health insurance, but in 2011 this had dropped to 31 percent (Shierholz, 2013). Over the same period, the share of high school graduates ages 17-20 with such coverage dropped from 24 to 7 percent, and those ages 19-24 with less than high school dropped from 16 percent to 5 percent. Health insurance is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 8.

Several young adults who spoke at the workshop emphasized the importance of being on trajectories leading toward employment. Shanae said her internship with Freddie Mac, which was organized through the Year Up program, “saved my life.” Year Up is a program for urban disadvantaged students who cannot afford to go to 4-year universities. It requires attendance at courses and strict adherence to a code of conduct, providing a model program for socioeconomically disadvantaged students. “When they said today, ‘the forgotten half,’ that is me,” said Shanae.

Jose, in recounting his experiences in both the juvenile and adult justice systems, said that when he was in prison, he mostly sat around and watched violent shows and movies on television. “What are we getting out of watching TV? What are we getting out of just fighting every day?” Prisons have to offer some opportunity for education for those who want it. Teachers can

become frustrated working with juveniles, he said. They can give up when too many of their students act up. But other inmates want to be educated. Prisons need to figure out something else for those who do not want to be taught and help those who do.

At 18, Jose now lives by himself and is struggling to pay the rent. What he wants now is to get an education, but he needs help to do so. Scholarships are difficult to get for students who do not have a record of educational achievement. Loans are available, but often only for students who are already doing well, and financial burdens can be a major reason for dropping out.

Young adults, and especially those with criminal records, can have a very hard time finding a job, he said. Working at fast food restaurants, for example, could help young adults who are unemployed or homeless. “We should have more jobs for those teenagers. They are going to be the future.”

Adolescents and young adults in the United States are becoming more ethnically and racially diverse, noted Deborah Rivas-Drake, assistant professor of education and human development at Brown University. Non-white ethnic and racial groups comprise 40 percent of young adults ages 18-24 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013), and this percentage is poised to increase, given that more than 50 percent of births in 2011 were to nonwhite women.

Hispanics and Latinos1 in particular have contributed substantially to this increasing diversification. Furthermore, Hispanics and Latinos, along with other groups, have become a larger percentage of the overall population in most parts of the country, not just in areas where they have historically been concentrated, such as large cities and the Southwest (Massey, 2008).

This diversification will continue. By the year 2060, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, non-Hispanic whites will be 43 percent of the population, compared with 63 percent today (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). His-panics will increase from 17 percent of the population to 31 percent, and Asians will increase from 5.1 percent to 8.2 percent. “Adolescents and

_________________

1 The terms “Hispanics” and “Latinos” used in this section refer to the following 2010 Census Bureau definition: “People who identify with the terms ‘Hispanic’ or ‘Latino’ are those who classify themselves in one of the specific Hispanic or Latino categories listed on the decennial census questionnaire and various Census Bureau survey questionnaires—‘Mexican, Mexican Am., Chicano’ or ‘Puerto Rican’ or ‘Cuban’—as well as those who indicate that they are’“another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.’ Origin can be viewed as the heritage, nationality group, lineage, or country of birth of the person or the person’s ancestors before their arrival in the United States. People who identify their origin as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be of any race” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

young adults will ultimately live in a plurality that looks more and more like they do—white, Latino, black, Asian, American Indian, and multiracial, among others,” said Rivas-Drake.

This increasing diversity presents both opportunities and challenges, said Rivas-Drake. In particular, diversification “holds great potential for increasing these minorities’ participation and contribution to the social, political, and economic well-being of this country.” Realizing this potential depends on micro-level processes (which involve individuals), meso-level processes (which involve social interactions), and macro-level processes (which involve social structures) (Deaux, 2006; Pettigrew, 1997).

At the micro level, how young people identify themselves in terms of race and ethnicity can have important social and psychological consequences (Rivas-Drake, 2012; Syed et al., 2013). For example, self-identification as biracial or multiracial has had important implications for how young people are counted and classified, as well as for how people experience race in a more flexible manner. Young people often make decisions about self-identification during the transition to adulthood, Rivas-Drake noted. “What are the sorts of meanings that young people ascribe to their membership in these groups?”

At the meso level, the interpersonal relationships of young adults can exert a strong influence on their life course, and researchers need to continue to expand their knowledge of these relationships, said Rivas-Drake. In particular, the existing literature suggests that the right conditions can foster intercultural understanding, appreciation, respect, and collaboration (Killen et al., 2011).

At the macro level, young adults have varying capacities to participate in the education, labor, and political systems of the nation. For example, disparities in the educational outcomes of different groups foreshadow a continued bifurcation in the life trajectories of these groups. Today, said Rivas-Drake, Hispanics are less likely to reach the levels of education attained by other groups, which means they will continue to be at an occupational and economic disadvantage in the future. Young adults also can experience ethnic or racial discrimination in education, employment, and other settings. According to survey results, 50 percent of Latinos ages 18-24 report experiencing discrimination (Perez et al., 2008), along with 87 percent of African American adolescents ages 13-17 (Seaton et al., 2008). Similar findings from other groups underscore the prevalence of social exclusion among diverse groups.

Given the links among education, socioeconomic status, social marginalization, and health, more research is needed to reveal the experiences of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups and the kinds of signals they get that can affect their future trajectories, Rivas-Drake concluded. Researchers also need to look at protective factors that buffer young people from nega-

tive experiences and processes. Socially inclusive systems that enable youth to participate fully in society can build “engaged, healthy, and productive individuals and communities.”

As America becomes more diverse, Andrea Vessel said during the presentations by young adults, students of color may no longer be as isolated as she has often been. She mentioned a recent posting on Facebook about “27 things you had to deal with as the only black kid in your class.” Vessel often felt that she had to represent her culture and prove herself. “Everyone is laughing around me, and I am just sitting here, like this is not fun.” At the same time, blacks who have not had the opportunities she has had can feel isolated from people, whether black or white, who have been successful. Today, people remain segregated by socioeconomic status, even if they are members of different races or ethnic groups. Perhaps greater diversity will ease some of these barriers among groups, she said.

THE USE OF TECHNOLOGY AND SOCIAL MEDIA

Young adults have come of age in a time of radical technological change, observed Amanda Lenhart, senior researcher and director of teens and technology at the Pew Research Center’s Internet Project. In the year 2000, connectivity to the Internet was slow and stationary. It relied on desktop computers, wired connections, and low data rates, so that use of video was uncommon. Only about half of U.S. adults had cell phones, and less than half used the Internet. “You got information from other people. It wasn’t an exchange of information. You weren’t creating information, and you weren’t in a position to have your voice be heard.”

Today, said Lenhart, 85 percent of adults in the United States use the Internet (Pew Research Center, 2013c), and 65 percent have a broadband connection at home (Pew Research Center, 2013a). Eighty-eight percent have a cell phone, and 55 percent are smartphone users (Smith, 2012). Two-thirds of adults use the Internet wirelessly, and 64 percent of online adults use social networking sites.2 “The fact that we are now untethered from that desk, and can connect to information and people wherever we go, is a huge innovation.”

Nearly all young adults use the Internet, said Lenhart, and most of them use social networking sites, which have become “a seamless part of how they expect to interact with people.” They also have virtually unlimited mobile access through their cell phones, so they can reach relatives or friends at any time. Among 18- to 29-year-olds, 93 percent have a cell phone and 65 percent have a smartphone, with black and Hispanic groups

_________________

2 For continuing analyses of these and related datasets, see The Pew Internet and American Life Project, http://www.pewinternet.org.

just as likely or more likely to use these devices as whites (Lenhart, 2013; Pew Research Center, 2013a,b,c). These are about the same percentages as for 30- to 49-year-olds, but young adults are in many cases the most enthusiastic users of these devices. For example, said Lenhart, 18- to 24-year-olds with cell phones send an average of 110 text messages a day, in comparison to 41 by an average adult. Of course, most young adults still like spending time with people, Lenhart said, but “absent that opportunity, text messaging is probably the way you are going to reach most young adults.”

About three-quarters of cell phone owners ages 18-29 have accessed the Internet from their mobile phones, and about 45 percent of this group access the Internet primarily from their mobile phones (Smith, 2012). This has implications for how they get information, said Lenhart. They are mostly using a small screen and accessing information on the go. Most phones may also be hooked into positioning systems so that the information can be keyed to where they are. Technology allows all phones to be tracked based on cell phone towers unless users specifically turn it off, but GPS enables more fine-grained tracking and does (generally) need to be enabled (or not disabled) by the user.

“They can find the closest McDonald’s, they can find the nearest ATM, they can find the nearest health clinic to get information about the condom that broke last night. There are all sorts of ways in which having the Internet in your pocket and having mobile access to information is radically changing how these teens and young adults go about getting access to information in their lives.”

A particular use of connectivity is to access social media. Young adults are not a monolith, given that 17 percent of them do not use social networking sites, but for the majority, social media are an important part of their lives (Lenhart, 2013). Facebook is the dominant platform for young adults, but other sites have also become popular, such as Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and Tumblr. Lenhart mentioned Snapchat as an example, which allows users to post a message or photograph that will disappear a few seconds later and not be stored on a computer.

Young adults use these sites, in part, to present themselves to the world. Whether a gang member, a college applicant, or a 14-year-old teenager with a large network of friends, a user of social media needs to decide how to portray his or her persona to the world. “It is a very complicated set of negotiations that young adults are having to go through, in terms of how to present themselves in those spaces and how to navigate the different audiences that are in each of these spaces,” said Lenhart. Some tend to use Twitter because of its simplicity, character limit, and the site’s on/off privacy setting (to reduce the size of communications). Others just post photos. With geolocation on phones, young adults can use these social sites to create their social life on the go. “This allows you to say, ‘Hey, I am at the

coffee shop down the road. Other people come and hang out with me.’” As an example, Lenhart described a site called Grindr, a dating website used by gay men that can be merged with social media to find and meet other gay men in the area.

These technologies give teens and young adults an opportunity to have their voices be heard, said Lenhart. They are recording and documenting their lives with the tools in their pocket, whether through photos, videos, or e-mail. Lenhart compared their phones to a Swiss Army knife that can do many different things, and young adults are more likely to use these capabilities than other adults (Smith, 2012).

New technologies also create a place where the missteps and mistakes of adolescents and young adults can be available publicly and for extended periods. Young adults may not “have the opportunity to get away from some of the things that they have done in their past,” said Lenhart. Young adults are often judged through the lens of adulthood, even though their brains are still developing and they are doing many things for the first time. In addition, social networking sites have been designed specifically to get users to share more information—in part so the sites can mine that information and profit from it. “It is a challenging environment for young adults,” said Lenhart.

An interesting topic that arose in the discussion session is the use of mobile technologies to record aspects of daily life that infringe on personal privacy. Larry Neinstein, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, mentioned a college student with a contract to record her entire first year, including parties, and make that information public. He also mentioned the problems posed by Google Glass, which can record any encounter with a person. “It is a new world we live in, and sometimes we don’t have good answers or good policies.” Young adults themselves can be frustrated by the constant sense of surveillance and never knowing when they might be photographed or videotaped. Photographs taken by others of underage students drinking have caused them to be suspended from school or disciplined in other ways, and facial recognition technologies could eventually make it possible to identify people almost anywhere. There are “a lot more challenges ahead,” Lenhart said. The relationship between social media and young adults’ health, safety, and well-being is explored further in Chapter 7.

This page intentionally left blank.