Important Points Made by the Speakers

- In young adulthood, unlike later in life, the primary public health burden is disability, not mortality. Among females, the greatest burden due to disability comes from mental health disorders. Among males, the greatest burden comes from substance use. (Davis)

- More than 60 percent of young adults have had experience with some kind of well-defined psychiatric disorder at some point in their life by the age of 25. (Copeland)

- The disconnect between child and adult mental health systems inhibits good quality and continuous mental health care. (Davis)

- Only about a quarter of the young adults with a psychiatric disorder are receiving services. (Copeland)

- Interventions that empower young adults, involve their peers, balance young adults and their families, and recognize the in-between status of young adults can overcome the fragmentation of many current services. (Davis)

- Even with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, potential precursors to psychosis provide an opportunity for intervention. (Seidman)

Mental health and substance use disorders are collectively the most impairing health conditions of young adulthood, yet the services young adults can access to counter these disorders are fragmented and uncoordinated. Three speakers at the workshop looked at mental health conditions, from those experienced by large percentages of young adults to much less common but severely disabling cases of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Young adults are disproportionately affected by mental health conditions, observed Maryann Davis, research associate professor with the Center for Mental Health Services Research in the University of Massachusetts Medical School’s Department of Psychiatry. In 2004 the World Health Organization published a global burden of disease study, which Gore et al. (2011) analyzed to characterize the burden of disease in young people ages 10-24 around the world. They found that in young adulthood, unlike later in life, the primary public health burden is disability, not mortality. In high-income countries like the United States, more than 80 percent of the total disease burden among young adults is attributable to disability.

Davis has further analyzed these data to look at females and males ages 15-19 and 20-24 in the United States. Among females, the greatest burden due to disability comes from mental health disorders, primarily bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia. Among males, the greatest burden comes from substance use.

For most mental health disorders, the best treatment is a combination of psychopharmacology and psychotherapy, Davis said. Psychotherapy is a psychosocial intervention—an exchange between a counselor and a young person, or a counselor, a young person, and that person’s family. But the unique cognitive and psychosocial development of young adults and their life circumstances can render either “child” or “adult” interventions inappropriate. Young adults are different than either young adolescents or mature adults. “It is a unique stage of life,” said Davis. “There is a very delicate dance going on between developing independence, interdependence, self-determination, being related to your family, taking advantage of the resources they can provide to you, while also trying to find yourself and your own independent means.”

Davis used suicide as an example of how interventions in young adults differ from those in adults. Young veterans who committed suicide had higher levels of nonalcohol substance problems, higher blood alcohol levels at the time of suicide, and a greater likelihood of relationship problems, whereas older veterans had more financial and medical problems (Kaplan et al., 2012). Suicide also is more likely to be associated with impulsive and

aggressive behaviors in younger adults (McGirr et al., 2008). Interventions need to reflect these differences to be most effective, said Davis.

Davis noted that young adults are more likely to drop out of mental health treatment compared with all adults. People ages 16-30 drop out of treatment more frequently than younger children or older adults (Davis, 2013). Individuals who drop out give a variety of reasons for leaving, such as loss of health care coverage or a feeling that the treatment is not relevant to their lives, but no research exists on how to develop interventions to help young adults stay in treatment long enough for it to have an effect.

Clinical trials typically lump adults from 18 to 55 together and do not break out results for young adults. Many trials have few young adult participants, which means that analyses to detect age differences cannot be done. Furthermore, interventions for young adults often are tested among college students, even though these students may not represent all young adults.

Davis listed several themes that are common in interventions being developed for young adults and their mental health conditions, though she emphasized that research on these themes is still in its early stages:

- Youth voice. All models put youth front and center and provide tools to support that role.

- Involvement of peers. Several interventions try to build on the strength of peer influence to produce better outcomes.

- Struggle to balance young person and family. No clear guidelines yet exist about how to involve parents or other family members in programs.

- Emphasize their in-between status. Many young adults are simultaneously working and going to school, living with their families and striving for independence, finishing schooling and beginning parenting, and so on.

Systems for juveniles and for adults are not well coordinated, Davis noted. For example, child mental health target population, definitions, and eligibility criteria are different from those of adult mental health systems, which tend to be much narrower. Even some young people who have been receiving intensive children’s mental health services as an adolescent will not get in the door of adult services once they age out of the juvenile system. “Nothing has changed about their need or their condition, but they no longer qualify,” Davis explained.

In addition, professionals have been trained to provide either child care or adult care. No professional training system exists for working with young adults. This lack of trained professionals provides another systemic barrier to delivering good mental health care for this population, along with

the fragmentation and discontinuity of care across the juvenile and adult health care systems.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has been designed to simplify enrollment in insurance plans and features outreach to underserved populations such as homeless youth. However, Davis expressed concern about whether young adults with mental health problems are going to be well served. Those who have well-developed safety net systems will be covered, “but for those who don’t, they are still going to be running out of health care.”

Research can help demonstrate how best to reach young adults. What are the interventions that appeal to them, get them into treatment, and help them stay in treatment? The use of social media or text messaging may be one way to encourage young people to seek treatment, Davis said. Raising awareness on college campuses and home-based treatments are other promising approaches. As part of a general improvement in their mental health literacy, young adults need to be able to recognize the initial stages of a mental health condition. Furthermore, tailored interventions and services need to be tested on a large scale, said Davis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF MENTAL HEALTH DISORDERS IN YOUNG ADULTHOOD

William Copeland, assistant professor at the Center for Developmental Epidemiology in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University Medical Center, has been working on a study that has tracked 1,400 children for 20 years, from childhood into their 30s. Using these valuable data, he and his colleagues have been able to answer critical questions about the magnitude of mental health issues in young adulthood.

At the broadest level, they have found that, across any 3-month interval, about 20 percent of the individuals in the study have met criteria for a well-defined psychiatric disorder. Of this 20 percent, 9 percent have met the criteria for one disorder, 6 percent have met the criteria for two disorders—for example, both an emotional disorder, either depression or anxiety, and a substance disorder—and 5 percent have met the criteria for three or more disorders.

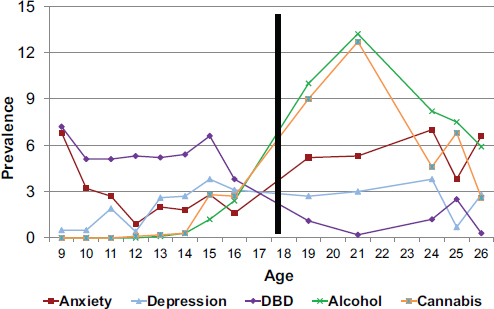

The rate of 3-month incidence varies by age and disorder (see Figure 6-1). Disorders involving alcohol and marijuana use jump dramatically after age 16, though nonsubstance-related disorders also undergo significant changes. Panic disorders go up dramatically at the end of the teen years and are still rising at 25. The incidence of depression increases in puberty, particularly with girls. Disruptive behavior disorders of childhood such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and op-positional defiant disorder disappear in adulthood because of the way they

FIGURE 6-1 Disorders due to alcohol and cannabis use peak in the early 20s.

NOTE: DBD = disruptive behavior disorder.

SOURCE: Copeland, 2013.

are defined, but the people with these disorders move into other systems that define disorders differently.

More than 60 percent of young adults have had experience with some kind of well-defined psychiatric disorder at some point in their life by the age of 25 (Copeland et al., 2011), with an even higher percentage having psychiatric symptoms and impairment that fall below the threshold for what constitutes a disorder. “It is normative for young adults to have had an experience with mental illness,” said Copeland.

Copeland’s group developed four scales of functioning in the areas of physical health, risky and criminal behavior, education and employment, and social functioning. They then compared young adults with no psychiatric disorder, those with a nonsubstance-related psychiatric disorder, and those with a substance-related disorder. Both of the groups with psychiatric disorders fared much worse than the no-disorder group across all four domains. For example, young adults with a disorder were twice as likely to report regular smoking, four times as likely to report police contact, twice as likely to have been fired from a job, three times as likely to have defaulted on a financial obligation, and four times as likely to be in a violent relationship. This constellation of problems can make it much more difficult for these individuals to achieve the customary milestones of young adulthood.

Of the young adults with a psychiatric disorder, 53 percent had some sort of disorder in childhood, and 24 percent had a subclinical problem, providing strong evidence for continuity of psychiatric problems. But the disorders of childhood do not necessarily predict those of adulthood, Copeland observed. “This isn’t just a case where depression in childhood predicts depression in young adulthood. It is anxiety predicting later depression, depression predicting later anxiety, conduct disorder predicting later depression, and so forth.”

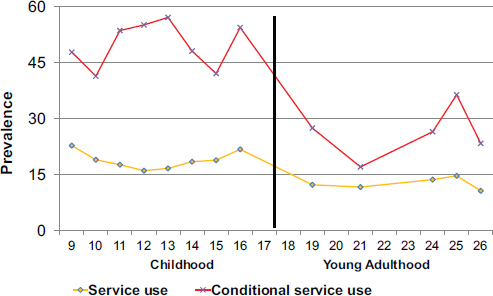

Finally, Copeland described the service usage rates in 39 different areas for both children and young adults (see Figure 6-2). For both services and conditional services—which is the use of a service by someone who has a disorder—the usage rates fell after adolescence. By the time people reach young adulthood, only about a quarter of the individuals with a psychiatric disorder are receiving services—half the rate as in childhood. The greatest drops are in specialty psychiatric services, educational and job services, and informal services, such as those offered by mentors, an Alcoholic Anonymous group, a Big Brother, or a spiritual advisor.

Young adults are transitioning out of their childhood homes, which explains part of this drop in services, because their parents are no longer

FIGURE 6-2 The use of services by those with mental health conditions falls from approximately 50 percent to about 25 percent when adolescents become young adults.

SOURCE: Copeland, 2013.

seeking services for them. On the other hand, as more children live with their parents into young adulthood, perhaps their use of services will increase, Copeland said.

Young adults are a group that “we absolutely need to prioritize,” he concluded. Rates of mental illness overall increase during young adulthood, yet only one in four young adults in need of services receives them, regardless of the quality of those services. “These folks are falling off of a bit of a cliff as they enter young adulthood.”

SCHIZOPHRENIA AND OTHER PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS

Larry Seidman, professor of psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, discussed a particular set of mental health disorders to demonstrate their effects on young adults: schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia has occurred throughout history in all countries. Prevalence rates vary somewhat—from 0.5 percent to 3 percent—with an average lifetime prevalence of a little less than 1 per 100. Though rarer than some mental health disorders, its effects can be devastating, and it is among the greatest contributors to the global burden of disease.

Schizophrenia is more common in males than females, with a typical age of onset for males of roughly 22 and for females of 27. The peak ages of onset are between 16 and 30, which is also the case for the major affective psychoses—bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder with psychotic features—which have about a 2 percent lifetime prevalence in total. The paucity of tools to identify who might progress to schizophrenia can lead to extended periods where psychotic symptoms go untreated—often years—during which people are fighting the disorder without assistance.

Careful interviews reveal that psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions occur more often that is usually presumed—in about 5 to 15 percent of children and adolescents. These symptoms do not always herald an impending psychotic disorder, but they are associated with higher rates of transition to psychosis. In the “premorbid period” for psychosis, which can be marked by a waxing and waning of symptoms, social and neurocognitive impairments are frequently present. For example, people who later develop schizophrenia may initially have cognitive or attention problems that progress to anxiety or flattened affect, withdrawal, educational failures, and attenuated psychotic symptoms.

Treatment outcome is better in first-episode patients the sooner antipsychotic drug treatments are initiated (Wyatt, 1991). Also, time to remission is a function of the prior untreated duration of psychosis (Lieberman et al., 1996). Cognitive enhancement therapy over 2 years has been shown to improve neurocognition modestly, improve social cognition substantially,

and reduce gray-matter loss in people in the early phase of schizophrenia (Eack et al., 2010). This treatment has also been shown to result in higher rates of return to school and work.

In rare cases, psychoses can lead to extreme violence, as in several recent shootings in the United States. Violence is significantly elevated in the first episode of psychosis, especially if it is untreated, ranging from any violence (in 34.5 percent of cases), to serious violence (16.6 percent), to severe violence leading to bodily harm to others (0.6 percent). The untreated psychotic period is the period of greatest risk to self and to others. While rare, homicides during first-episode psychosis occurred at a rate of 1.6 homicides per 1,000, which is equivalent to 1 in 629 presentations (Nielssen and Large, 2010). In contrast, the annual rate of homicide after treatment for psychosis was 1/15th the rate for first episodes, pointing again to the need for early intervention.

The potential precursors to psychosis provide an opportunity for intervention, said Seidman. The view that the progression to schizophrenia is inexorable is “wrong and outmoded,” he said. Structured instruments now can be used to diagnose a high-risk period before psychosis begins, but when it is clearly brewing. Antipsychotic medications and cognitive behavior therapy during the clinical high-risk period may attenuate the symptoms or delay the onset of psychosis. More research is clearly needed, but the results to date suggest a 10 percent conversion rate to psychosis in treated subjects compared with 30 percent in untreated subjects. “There is a beginning sense that we could actually prevent psychoses and certainly reduce disability.”

Mental health literacy about schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders is very low. Patients and families tend to engage in denial and ignore symptoms, and many mental health providers have limited knowledge of schizophrenia. In addition, the United States has a lack of access to treatment and very limited services for prodromal and first-episode psychosis— roughly 10 to 20 programs nationwide, compared with 50 to 100 programs in the United Kingdom.

Young adults get much of their information from the Internet. Websites where they can answer questions about symptoms they might have can be extremely valuable. Hospitalization is important and can save lives, but earlier intervention may avoid the trauma and expense of hospitalization and help provide continuity of care with an outpatient clinician.

Community awareness of warning signs and early referral are critical to reach those who can benefit, and early intervention may prevent cognitive loss and violence to self or others, Seidman said. For example, screening items for a pediatrician or primary care provider may be the best way to reach the maximum number of people. The earlier psychosis is detected and treated, the better the prognosis.

During the presentations by the young adults, Shanae recounted the story of a man who was in her high school graduating class and committed suicide in a Washington, DC, correctional facility. He had schizophrenia, but was not given a mental examination, even though his father requested one. “With schizophrenia, someone should be watching you,” she said. “You leave someone with schizophrenia in a cell with sheets, with anything they could possibly hang themselves with, that means you weren’t doing your job.”

This page intentionally left blank.