Key Points Raised by Individual Speakers

• Various neuromuscular and neurodegenerative diseases— including certain types of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease—feature toxic RNA or RNA-binding proteins.

• Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are diverse classes of RNA molecules that are not translated into proteins. They are disproportionately expressed within the central nervous system, where they have roles in gene expression, development, neural network plasticity and connectivity, stress response, and brain aging. Base pair mutations to ncRNA can have widespread biological effects in light of ncRNA’s unusually broad and interconnected gene and cellular regulatory roles, and they are implicated in neurodegenerative disease.

• Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are being tested to treat RNA errors in human neurodegenerative disease. ASOs are designed to hybridize and then to block disease-related RNA sequences. ASOs have reached the point of being tested in a clinical trial of the neuromuscular disorder spinal muscular atrophy.

“Errors in RNA” is a generic term used here to refer to disease-related defects of three types: (1) defects in RNA itself; (2) defects in RNA-binding proteins that form ribonucleoprotein complexes with RNA; or (3) defects in proteins responsible for RNA assembly.1 Defects of each type can hold deleterious effects that are broadly amplified because of RNA’s regulatory roles in transcription, translation, epigenetic modification, and a host of other processes (Taft et al., 2010). Disease-causing RNAs can be in protein coding mRNAs or in non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), both of which can disrupt crucial cell functioning (Cooper et al., 2009).

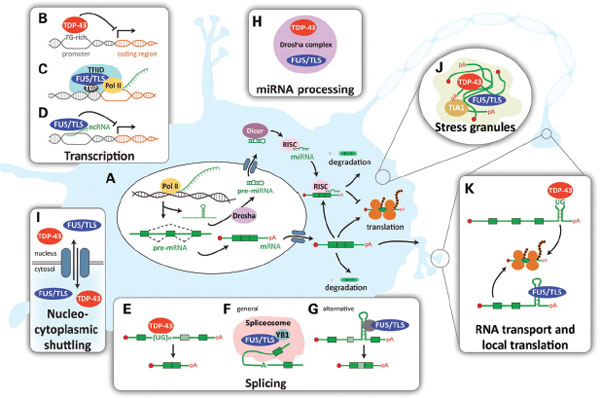

In his opening remarks about the interest in examining RNA errors in human neurodegenerative diseases, Don Cleveland of the University of California at San Diego outlined a constellation of exciting recent discoveries that have identified toxic RNA-binding proteins in neurodegenerative disease. It has only been known for 6 years that dominant mutations in TDP-43 and FUS/TLS genes cause familial ALS and some rare cases of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. A wave of new research has established that the protein products of these genes are RNA-binding proteins that appear to be involved in multiple steps of RNA processing, such as alternative splicing, transcription, nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, or RNA transport (Lagier-Tourenne et al., 2010) (see Figure 6-1). Mutant TDP-43 protein-RNA alters nearly 1,000 splicing events (Polymenidou et al., 2011). Relatedly, spinal muscular atrophy is caused by a recessive loss of the RNA-binding protein SMN. Finally, the most prominent cause of inherited ALS is a GGGGCC hexanucleotide expansion in the C9orf72 gene.

This chapter of the workshop summary examines errors in RNA, including in RNA-binding proteins, their roles in neurological and neurodegenerative disease, and novel therapies to combat RNA errors. Unlike protein aggregation, which is well known as a pathological feature common to many neurodegenerative diseases, the recognition that there are errors in RNA in a series of neurodegenerative diseases is currently emerging, and these errors may not be regarded as primary pathogenic mechanisms in some conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease.

RNA GAIN OF FUNCTION MECHANISMS IN NEUROGENERATIVE DISEASE: MICROSATELLITE EXPANSION DISORDERS

Microsatellite expansion disorders are ones in which mutations are repeating sequences of base pairs of DNA. Huntington’s disease, for example, features a CAG expansion, leading to excess copies of the amino acid glutamine in the huntingtin protein. Laura Ranum of the University of Florida focused her presentation on the microsatellite expansion disorder

1 Proteins that bind to RNA also bind to DNA.

FIGURE 6-1 Proposed physiological roles of TDP-43 and FUS/TLS.

(A) Summary of major steps in RNA processing from transcription to translation or degradation. (B) TDP-43 binds single-stranded TG-rich elements in promoter regions, thereby blocking transcription of the downstream gene (shown for TAR DNA of HIV and mouse SP-10 gene). (C) FUS/TLS associates with TBP within the TFIID complex, suggesting that it participates in the general transcriptional machinery. (D) In response to DNA damage, FUS/TLS is recruited in the promoter region of cyclin D1 (CCND1) by sense and antisense non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and represses CCND1 transcription. (E) TDP-43 binds a UG track in intronic regions preceding alternatively spliced exons and enhances their exclusion (shown for CFTR and apolipoprotein A-II). (F) FUS/TLS was identified as a part of the spliceosome and (G) was shown to promote exon inclusion in H-ras mRNA, through indirect binding to structural regulatory elements located on the downstream intron. (H) Both proteins were found in a complex with Drosha, suggesting that they may be involved in miRNA processing. (I) Both TDP-43 and FUS/TLS shuttle between the nucleus and the cytosol and (J) are incorporated in SGs, where they form complexes with mRNAs and other RNA-binding proteins. (K) TDP-43 and FUS/TLS are both involved in the transport of mRNAs to dendritic spines and/or the axonal terminal where they may facilitate local translation. Examples of such cargo transcripts are the low molecular weight NFL for TDP-43 and the actin-stabilizing protein Nd1-L for FUS/TLS.

NOTE: For additional details and citations associated with each of these proposed roles, see the source article.

SOURCE: Lagier-Tourenne et al., 2010.

myotonic dystrophy, a prominent example of RNA disruption, and she also focused on a new type of protein translation process that defies the canonical rules of molecular biology.

Myotonic dystrophy is a slowly progressive neuromuscular disease marked by wasting muscles, cataracts, heart conduction defects, endocrine defects, and myotonia, which is a slow relaxation of the muscles after voluntary contraction. Myotonic dystrophy comes in two different types: type 1, which is caused by a CTG expansion in the 3' untranslated region of the DMPK gene, and type 2, which is caused by a CCTG expansion in the intron in the ZNF9 gene (Ranum and Cooper, 2006). In both cases, the gene mutations encode an aberrant expansion containing RNAs that sequester proteins that normally regulate alternative splicing. As a consequence, these sequestered proteins fail to participate in their normal function of regulating alternative splicing. The associated splicing defects affect hundreds and thousands of genes, depending on the tissue. In transgenic animals with myotonic dystrophy, mis-splicing of a chloride channel causes myotonia, and mis-splicing of the insulin receptor is thought to lead to insulin resistance that is associated with the disease, noted Ranum.

In the process of studying myotonic dystrophy and the neurodegenerative disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 8, which features a CAG expansion (Koob et al., 1999), Ranum and colleagues uncovered an entirely new and surprising type of translation process for converting an RNA into protein: Repeat associated non-ATG (RAN) translation. According to the canon of molecular genetics, translation requires the initiating DNA sequence ATG—also known as the start codon. But her research showed that the ATG sequence was not required to translate CAG and CUG expansions. She and her colleagues showed that RAN translation takes place in vivo in myotonic dystrophy and spinocerebellar ataxia type 8 (Zu et al., 2011). They also showed that RAN translation is favored by hairpin turns and long repeats of DNA, as well as by cellular factors. She concluded her presentation by asking three key questions that need to be addressed in future research: (1) What is the role of RNA versus protein effects in neurodegenerative disease?, (2) How and why are RAN proteins expressed?, and (3) Is RAN translation a previously unrecognized pathogenic mechanism in neurodegenerative disease?

EMERGING ROLES OF NON-CODING RNA NETWORKS IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASE

ncRNAs are diverse classes of RNA molecules that are not translated into proteins. They exert complex regulatory and structural functions, including the biogenesis and function of nuclear organelles. According to various sequencing methods, there are likely to be hundreds of thousands

to millions of ncRNAs in the human genome. In fact humans have the highest number of non-coding sequences relative to other species in the animal kingdom (Mattick, 2007). A large fraction of ncRNAs is expressed within the central nervous system. There they participate in controlling gene expression, development, neural network plasticity and connectivity, stress response, and brain aging (Qureshi and Mehler, 2011). If an ncRNA has a mutated base or changes in expression, as appears to occur in certain neurodegenerative and other neurological diseases, it can potentially alter any or even all of these regulatory functions. Thus it is not surprising that ncRNAs have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, noted Mark Mehler of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. In one example, a non-coding antisense RNA against β-secretase (BACE1-AS) may be a contributor to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease by increasing BACE1 expression (Faghihi et al., 2008). BACE1 is an enzyme that cleaves amyloid precursor protein to generate fragments of the neurotoxic protein amyloid-β peptide (Aβ). The study showed elevated BACE1-AS in the postmortem brains of Alzheimer’s cases.

ncRNAs bear four key features. First, they have low bioenergetic demand, meaning that to change their biophysics and conformational properties, they require about 20 percent of the energy demand of proteins. This is highly important, said Mehler, because every neurodegenerative disease is fundamentally a disease of bioenergetic failure. Second, ncRNAs are highly sensitive to intracellular and extracellular stimuli, conferring a link between genes and the environment. “ncRNAs are the most exquisite biosensors known,” Mehler said. Third, ncRNAs are versatile: They uniquely interact with DNA, RNA, and proteins. Fourth, they exhibit diverse roles in epigenetic regulation, such as promoting DNA methylation, chromatin modification, and RNA editing. Epigenetics is changing the research landscape, considering that every cell in the brain has a unique epigenome that changes constantly because it is reflective of dynamic gene–environment interactions, Mehler added.

A final noteworthy feature of ncRNAs is their trafficking capacity. Not only do they shuttle intracellularly, but they are also transmissible by virtue of being secreted by cells within discrete classes of vesicles, including microvesicles and exosomes. Recent research has established that exosomes bearing ncRNAs, mRNAs, DNA, lipids, and protein products traffic not just between adjacent cells, but also through the bloodstream to other organs and potentially to the germ line. There is evidence, said Mehler, that mRNA in an exosome can be translated to protein in a recipient cell. It is even possible that ncRNAs account for some of the transmissibility of neurodegenerative disease-associated pathology. “The real take-home message is that this is a field where networks are going to be important,” observed Mehler.

ANTISENSE OLIGONUCLEOTIDES AS THERAPIES FOR RNA-BINDING PROTEIN ERRORS

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are a class of emerging treatments for RNA errors in neuromuscular and neurodegenerative disease. ASOs are single strands of complementary base pairs that hybridize to highly specific target RNA sequences. Their role is first to hybridize and then to block the disease-related sequences from forming, or from functioning properly once they are formed. As a result of high specificity, ASOs possess the attractive feature that they minimize the likelihood of side effects. Frank Rigo of ISIS Pharmaceuticals described his approach to ASOs by pointing out that they are well suited for diseases with or without a known genetic cause and that are amenable to direct RNA therapeutic correction. The ASOs that ISIS develops work in one of two ways: by a Ribonuclease H method that cleaves and degrades the RNA once the ASO binds to the target sequence, or by a mechanism that modulates splicing. The latter approach is being used to treat spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in a Phase I clinical trial, which is currently under way.

SMA is an autosomal recessive neuromuscular disorder marked by muscle atrophy and weakness. It is the leading genetic cause of death in infants and toddlers. It is caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene that lead to absence of the SMN protein, which is necessary for motor neuron survival. SMN1 protein is necessary for assembly of certain ribonucleoproteins. A very close copy of the gene, SMN2, is unable to compensate for the loss of SMN1 because exon 7 of the SMN2 gene fails to be transcribed, the result of which leads to an unstable SMN2 protein that is rapidly degraded. Rigo and colleagues successfully developed an ASO designed to prevent binding of certain splicing repressors in a manner that ensured inclusion of exon 7 in a transgenic mouse model that carries human SMN2 (Passini et al., 2011). Expression of the SMN2 protein is restored and can compensate for the lack of SMN1 expression. The treatment led to profound increase in survival of the SMA mouse model (Hua et al., 2011).

ASOs, noted Rigo, can be delivered systemically or centrally. The ASOs are endocytosed across the neuron cell membrane and make their way to the nucleus. He and his colleagues have shown in non-human primates that ASOs, delivered intrathecally, broadly distribute to central nervous system tissues, with the greatest concentrations in spinal cord gray matter and cortical regions. The lowest concentrations appear in subcortical regions. The ASOs have remarkably long half-lives of several months, a feature that makes them highly attractive considering that the route of administration is intrathecal. In a Phase I trial of an ASO targeted at the SOD1 mutation in ALS, the investigators have found good correspondence between human

pharmacokinetics as compared with that in non-human primates. The drug was well tolerated and no safety concerns were identified.

Rigo reported that ISIS has developed clinical experience with SMA and ALS, while myotonic dystrophy type I and familial dysautonomia are currently at the preclinical stage. They are also pursuing Huntington’s disease by reducing the expression of the huntingtin protein with an ASO that operates by the ribonuclease H approach. They are also looking to reduce tau expression in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia by both ribonuclease H and non-ribonuclease H approaches.

Despite progress, Rigo asserted that there are clear challenges to drug development for neurological disorders. Most diseases have relatively small patient populations, but they are still commercially attractive because of unmet medical need. He observed that ASO research and development comes with a great deal of risk, primarily because there are no established pharmacodynamic biomarkers for early drug efficacy: Measuring the target protein in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma is generally difficult. Uncertainty also surrounds regulatory and clinical development. To mitigate the risks, ISIS is working closely with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). He said that his company has succeeded thus far by actively seeking regulatory input and fostering interactions with the FDA.

One of the most important challenges is to develop biomarkers, which will become highly important for gaining drug approval. Rigo said his company is trying to establish biomarkers for early indication of drug efficacy through expression analyses and proteomics. Without biomarkers it is more challenging to determine how to dose humans and how to follow pharmacodynamics over time.

When queried about regulatory problems in the discussion session, Rigo stressed the importance of meeting early with the FDA and being “engaged in an education process.” He emphasized that there are no currently approved ASOs in neurodegenerative disease, which means that there is no clearly established path to drug approval. Story Landis of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke suggested that he may wish to use her institute’s Phase II clinical trials network. Landis asked: Once you have experience with one oligonucleotide, can this be applied to other oligonucleotides? Rigo responded: Yes, but a thorough safety evaluation for each oligonucleotide is needed.

RESEARCH NEEDS AND NEXT STEPS SUGGESTED BY INDIVIDUAL PARTICIPANTS

The speakers at the workshop identified many questions for future research and other opportunities for future action. The suggestions related to errors in RNA are compiled here to provide a sense of the range of sug-

gestions made. The suggestions are identified with the speaker who made them and should not be construed as reflecting consensus from the workshop or endorsement by the Institute of Medicine.

• Establish pharmacodynamic biomarkers for early drug efficacy readout because of the difficulty of measuring the target RNA-binding proteins in cerebrospinal fluid or plasma. (Rigo)

• Establish a clear clinical development path to drug approval because there are no currently approved disease-modifying drugs for many neurodegenerative diseases. (Rigo)

• Determine how and why RAN proteins are expressed. (Ranum)

• Identify the roles of RNA versus protein effects in disease. (Ranum)

• Discern whether RAN translation is a previously unrecognized pathogenic mechanism in neurodegenerative disease. (Ranum)

• Determine whether neural subtype-specific ncRNA networks contribute to selective regional cellular vulnerabilities. (Mehler)

• Identify the role of extracellular trafficking of ncRNAs and whether this novel process can lead to local and long-distance propagation of pathology. (Mehler)