The Current Cancer Care Landscape: An Imperative for Change

This chapter documents the major drivers creating an imperative for change in the cancer care delivery system: (1) the changing demographics in the United States and the increasing number of cancer diagnoses and cancer survivors and (2) the challenges and opportunities in cancer care, including trends in cancer treatment, unique considerations in treating older adults with cancer, unsustainable cancer care costs, and federal efforts to reform health care. The chapter concludes with a section outlining the key stakeholders who will be responsible for transforming the cancer care delivery system, setting the stage for the report’s subsequent chapters, which address the committee’s recommendations for overcoming challenges to delivering high-quality cancer care.

The changing demographics in the United States will exacerbate the most pressing challenges to delivering high-quality cancer care. From 2010 to 2050, the United States is expected to grow from more than 300 million to 439 million people, an increase of 42 percent (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). Although the overall growth rate of the population is slowing, the older adult population, defined in this report as individuals over the age of 65, continues to experience remarkable growth (Mather, 2012; Smith et al., 2009). The diversity of the population is also increasing (Smith et al., 2009). This section explores these trends in detail as well as trends in cancer diagnosis and survivorship.

The Aging Population

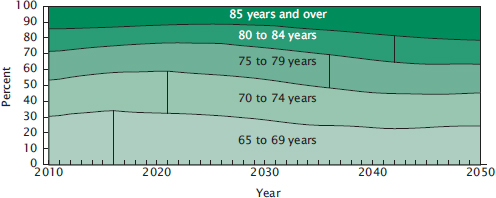

Between 1980 and 2000, the older adult population grew from 25 million to 35 million and it is expected to comprise an even larger proportion of the population in the future (Smith et al., 2009). Projections show that by 2030, nearly one in five U.S. residents will be age 65 and older. By 2050, the older adult population is expected to reach 88.5 million, more than double that in 2010 (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). The baby boomer generation, the first of whom turned 65 in 2011, is largely responsible for the projected population increase. As the baby boomer generation ages, the older adult population over 85 years will rapidly increase: in 2010, around 14 percent of older adults were 85 years of age and older; by 2050, that proportion is expected to grow to more than 21 percent (see Figure 2-1) (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). Thus, not only is the U.S. population getting older, the older adult population is getting older.

Increasing Diversity of the Population

Growing racial and ethnic diversity in the United States are important demographic trends influencing the delivery of high-quality cancer care. The two major factors contributing to this increasing diversity include (1) immigration and (2) differences in fertility and mortality rates (Shrestha and Heisler, 2011). From 1980 to 2000, racial and ethnic minorities (i.e., non-White) grew from 46 million to 83 million and are expected to expand

FIGURE 2-1 Distribution of the projected older population by age in the United States, 2010 to 2050.

NOTE: Vertical line indicates the year that each age group is the largest proportion of the older population. Data are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2008 National Population Projections.

SOURCE: Vincent and Velkoff, 2010.

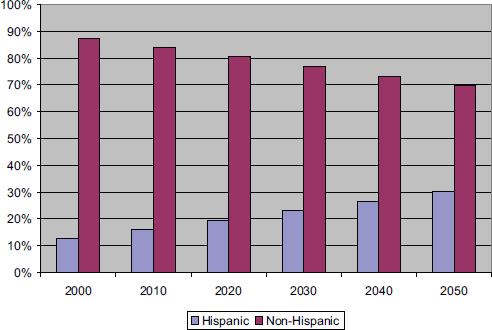

to 157 million by 2030 (see Table 2-1 and Figure 2-2) (Smith et al., 2009).1 The Hispanic population, for example, is one of the fastest-growing segments of the U.S. population; if current demographic trends continue, the proportion of Hispanic individuals will rise from 12.6 percent of the population in 2000 to 30.2 percent in 2050 (Shrestha and Heisler, 2011).

Racial and ethnic minorities are much younger than the overall U.S. population. As a result, the older adult population in the United States is not as racially and ethnically diverse as the U.S. population as a whole. As the minority population ages over the next four decades, the older adult population is expected to become more diverse. Minorities are projected to comprise 42 percent of the older adult population by 2050, a 20 percent increase from 2010 (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010). The Hispanic population age 65 and older is projected to increase by more than sixfold from 2010 to 2050, compared to the non-Hispanic population, which is expected to double during this same time period (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010).

The male-to-female ratio in the older adult population is also expected to shift in the coming decades. The U.S. population has traditionally included more females than males due to women’s longer life expectancy. With the life expectancy among males quickly rising, the percentage of females 65 years and older will decrease from 57 percent of the older population in 2010 to 55 percent in 2050 (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010).

Trends in Cancer Diagnoses

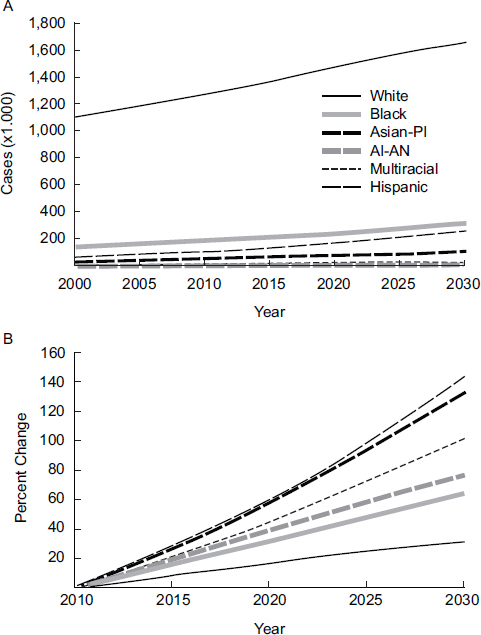

From 1980 to 2000, the U.S. population grew from 227 million to 279 million (a 23 percent increase). During that same time period, the total yearly cancer incidence increased from 807,000 to 1.34 million (a 66 percent increase) (Smith et al., 2009). Future projections indicate that between 2010 and 2030, the U.S. population will increase from 305 million to 365 million (a 19 percent increase), while the total cancer incidence will rise from 1.6 million to 2.3 million (a 45 percent increase) (Smith et al., 2009). Thus, the incidence of cancer is rapidly increasing (see Figure 2-3).

Men are more likely than women are to be diagnosed with cancer. Current estimates place the overall lifetime risk of developing cancer in men at around one in two and for women around one in three; the incidence rate for all cancers combined is 33 percent higher in men than in women (ACS, 2012b; Eheman et al., 2012). More than 1.6 million individuals will be diagnosed with cancer in 2013 (854,790 in men and 805,500 in women) (NCI, 2013a). The three most common cancers in men

____________________

1 Federal standards for collecting information on race and Hispanic origin were established by the Office of Management and Budget in 1997 and revised in 2003. Race and ethnicity are discussed as distinct concepts in this report (OMH, 2010; Shrestha and Heisler, 2011).

TABLE 2-1 Projected U.S. Population, by Race: 2000-2050

| Population | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 |

| Total | 282,125 | 310,233 | 341,387 | 373,504 | 405,655 | 439,010 |

| (100.0) | (100.0) | (100.0) | (100.0) | (100.0) | (100.0) | |

| White alone | 228,548 | 246,630 | 266,275 | 286,109 | 305,247 | 324,800 |

| (81.0) | (79.5) | (78.0) | (76.6) | (75.2) | (74.0) | |

| African American alone | 35,818 | 39,909 | 44,389 | 48,728 | 52,868 | 56,944 |

| (12.7) | (12.9) | (13.0) | (13.0) | (13.0) | (13.0) | |

| Asian alone | 10,684 | 14,415 | 18,756 | 23,586 | 28,836 | 34,399 |

| (3.8) | (4.6) | (5.5) | (6.3) | (7.1) | (7.8) | |

| All other races | 7,075 | 9,279 | 11,967 | 15,081 | 18,704 | 22,867 |

| (2.5) | (3.0) | (3.5) | (4.0) | (4.6) | (5.2) | |

NOTES: In thousands, except as indicated. Resident population. Numbers may not add due to rounding.

SOURCE: Shrestha and Heisler, 2009.

FIGURE 2-2 Hispanics and non-Hispanics as a percentage of the U.S. population, 2000-2050.

NOTE: For the years 2010-2050, data are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2008 National Population Projections. For 2000, data are from Congressional Research Service extractions from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2004 U.S. Interim National Population Projections.

SOURCE: Shrestha and Heisler, 2011.

are prostate, lung, and colorectal cancer, and the three most common in women are breast, lung, and colorectal cancer (CDC, 2012a,b). The greater incidence of cancer in men is often attributed to higher rates of tobacco use, obesity, physical inactivity, and prostate-specific antigen screening (Andriole et al., 2012; CDC, 2013; KFF, 2013b).

Some minority populations are at an increased risk for cancer (IOM, 1999) (see Table 2-2). African American men consistently have the highest cancer incidence rate of all racial and ethnic groups, with overall rates 15 percent higher than for white men and almost twice that for Asian/Pacific Islander men (Eheman et al., 2012). In addition, the cancer incidence rate is expected to grow faster among racial and ethnic minorities than for Whites (Smith et al., 2009). From 2010 to 2030, the percentage of cancers diagnosed in racial and ethnic minorities is expected to increase from 21 to 28 percent of all cancers (Smith et al., 2009). The causes of these racial and ethnic disparities in risk are complex and overlapping, and they can

NOTE: AI = American Indian; AN = Alaska Native; PI = Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: Smith, B. et al: J Clin Oncol 27(17), 2009: 2758-2765. Reprinted with permission. © 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

TABLE 2-2 Cancer Incidence Rates by Race, 2006-2010, from 18 SEER Geographic Areas

| Cancer Incidence Rates by Race and Ethnicity | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | Male | Female |

| All Races | 535.9 per 100,000 men | 411.2 per 100,000 women |

| White | 539.1 per 100,000 men | 424.4 per 100,000 women |

| African American | 610.4 per 100,000 men | 397.5 per 100,000 women |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 335.06 per 100,000 men | 291.5 per 100,000 women |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 351.3 per 100,000 men | 306.5 per 100,000 women |

| Hispanic | 409.7 per 100,000 men | 323.2 per 100,000 women |

NOTE: SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program.

SOURCE: NCI, 2013a.

include socioeconomic status (SES); unequal access to care; differences in behavioral, environmental, and genetic risk factors; and social and cultural biases that influence the quality of care (AACR, 2012; ACS, 2011).

SES is another predictor of cancer incidence and morbidity (Clegg et al., 2009). People with lower SES are disproportionately affected by many cancers, including lung, late-stage prostate, and late-stage female breast cancer (ACSCAN, 2009; Booth et al., 2010; Clegg et al., 2009). These disparities in people with lower SES are often attributed to differences in cancer preventive behaviors, health insurance status, and an inability to access and afford timely screening and appropriate follow-up care (ACSCAN, 2009).

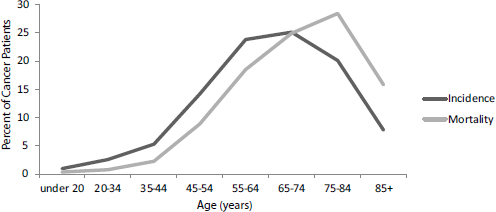

Finally, one of the strongest risk factors for cancer is age (see Figure 2-4) (ACS, 2012b; NCI, 2013a). The median age for a cancer diagnosis is 66 years of age (NCI, 2013a). In general, as age increases, cancer incidence and mortality increase (NCI, 2013a). As more of the population reaches 65 years of age, cancer incidence is expected to increase.

Trends in Cancer Survivorship

The Institute of Medicine previously adopted the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship’s definition of a cancer survivor as a person who has been diagnosed with cancer, from the time of diagnosis through the balance of life (IOM and NRC, 2005). Since the “war on cancer” began in 1971, changes in screening and treatment have contributed to an almost fourfold increase in the number of survivors (NCI, 2012a; Parry et al., 2011). Out of a U.S. population of more than 300 million people, approximately 14 million people are cancer survivors (see Table 2-3) (ACS, 2012c;

FIGURE 2-4 Age-specific incidence and mortality rates for all cancers combined, 2006-2010.

SOURCE: NCI, 2013a.

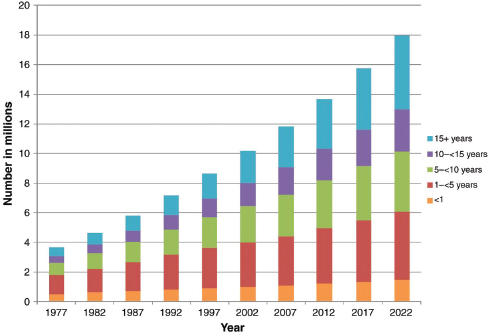

U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Projections estimate that the total number of cancer survivors will reach 18 million (8.8 million males and 9.2 million females) by 2022 (see Figure 2-5) (ACS, 2012c; de Moor et al., 2013).

Average survival time following a cancer diagnosis is growing longer. As a result, there are more adults living with a history of cancer throughout their lifetime (Parry et al., 2011). In the current population of cancer survivors, 64 percent were diagnosed more than 5 years ago and 15 percent were diagnosed more than two decades ago (ACS, 2012c). The majority of these survivors are older adults (ACS, 2012c; Parry et al., 2011). In addition, the number of cancer survivors over the age of 65 years is expected to increase at a faster rate than for any other age group; by 2020, 11 million cancer survivors will be older adults, a 42 percent increase from 2010 (Parry et al., 2011). Box 4-3 in Chapter 4 discusses various workforce strategies that are being utilized to care for this growing population of cancer survivors.

The increases in survival following a cancer diagnosis, however, have not been equitable across all segments of the population (IOM, 1999). Recent policy initiatives, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)2 provision on understanding health care disparities (see Annex 2-1) and the Healthy People 2020 initiative, are designed to gather data on health care disparities and promote health equity. Current data indicate that there are major disparities in cancer outcomes among people

____________________

2 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148, 111th Congress (March 23, 2010).

TABLE 2-3 Estimated Number of U.S. Cancer Survivors by Sex and Age as of January 1, 2012

| Male | Female | |||||

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |||

| All ages | 6,442,280 | 7,241,570 | ||||

| 0-14 | 36,770 | 1 | 21,740 | <1 | ||

| 15-19 | 24,860 | <1 | 23,810 | <1 | ||

| 20-29 | 74,790 | 1 | 105,110 | 1 | ||

| 30-39 | 134,630 | 2 | 250,920 | 3 | ||

| 40-49 | 350,350 | 5 | 647,840 | 9 | ||

| 50-59 | 930,140 | 14 | 1,365,040 | 19 | ||

| 60-69 | 1,705,730 | 26 | 1,801,430 | 25 | ||

| 70-79 | 1,858,260 | 29 | 1,607,630 | 22 | ||

| 80+ | 1,326,740 | 21 | 1,418,050 | 20 | ||

NOTE: Data are from the Data Modeling Branch, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute. Percentages may not sum to 100 percent due to rounding.

SOURCE: American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship: Facts and Figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. ACS, 2012c.

who have lower SES, are racial and ethnic minorities, and people who lack health insurance coverage (ACS, 2011; ACSCAN, 2009; AHRQ, 2011b, 2012b). The committee addresses the importance of ensuring that cancer care is accessible and affordable to all individuals in Chapter 8.

SES is an important factor in cancer survival and cancer death (ACS, 2011; IOM, 1999). For example, the 5-year cancer survival rate is 10 percentage points higher among people who live in affluent areas compared to people who live in poorer areas (Ward et al., 2004). People who have lower SES (measured by years of education) are more likely to die from cancer compared to people who have higher SES, regardless of other demographic factors; this disparity is likely to increase (ACS, 2011). There are several possible explanations for the correlation between low SES and poor cancer survival. Individuals with low SES often lack access to preventive care or cancer treatment due to the high cost of care, lack of health insurance, poor health literacy, or because they live in poor or rural areas that are geographically isolated from clinicians (ACS, 2011). As a result, these individuals may be more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancers, which could have been treated more effectively if diagnosed earlier. In addition, an individual’s SES can influence the prevalence of

SOURCE: Reprinted from Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2013, 22(4), 561-570, de Moor, Cancer survivors in the United States: Prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care, with permission from AACR.

behavioral risk factors for cancer, including tobacco use, poor diet, and physical inactivity, as well as the likelihood of following cancer screening recommendations (ACS, 2011; NCI, 2008). People with less education, for example, are more likely to smoke and those with lower incomes are less likely to exercise than people with higher education and incomes (ACSCAN, 2009).

Some racial and ethnic groups have poorer survival and higher cancer death rates compared to other groups (ACS, 2013b). From 1999 to 2008, overall cancer death rates appreciably declined in every racial and ethnic group except American Indian and Alaska Native populations (Eheman et al., 2012). African Americans have the highest death rate of all racial and ethnic groups; the death rate for all cancers combined is 31 percent higher in African American men compared to White men and 15 percent higher for African American women compared to White women (ACS, 2013a). African Americans also have a lower 5-year overall survival rate from cancer than Whites (60 percent versus 69 percent) (ACS, 2013a).

Asian Americans generally have lower cancer death rates than Whites; however, disparities in survival exist for certain types of cancers, such as stomach and liver cancer (NCI, 2012d; OMH, 2012). Death rates are lower among Hispanics than among non-Hispanic Whites for all cancers combined and for the four most common cancers (prostate, female breast, colorectal, and lung) (ACS, 2012a). Table 2-4 provides overall cancer death rates by race and ethnicity.

As noted previously, the factors contributing to racial and ethnic disparities in cancer outcomes are complex and overlapping, and they can include low SES; unequal access to care; differences in behavioral, environmental, and genetic risk factors; and social and cultural biases that influence the quality of care (AACR, 2012; ACS, 2011). African Americans are often diagnosed at later stages of disease than are Whites, when the severity is greater and the odds of survival are poorer (ACS, 2013a; AHRQ, 2011b, 2012b). Although Hispanics have lower cancer death rates than Whites, they too are often diagnosed at later stages of disease than are Whites (ACS, 2012a). Patient beliefs and choices may contribute to the later stage of diagnosis (Espinosa de los Monteros and Gallo, 2011; Margolis et al., 2003; Stein et al., 2007). Racial and ethnic minorities may be more skeptical about the medical community due to past incidents of mistreatment (IOM, 1999, 2003). In addition, problems in communication and coordination of care may contribute to the disparities in treatment outcomes. According to one study, racial and ethnic minorities and non-English speakers were less likely to report that they had received excellent or very good cancer care than were Whites, and analyses found that a

TABLE 2-4 Death Rates by Race in 2006-2010 from 18 SEER Geographic Areas

| Death Rates by Race and Ethnicity | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | Male | Female |

| All Races | 215.3 per 100,000 men | 149.7 per 100,000 women |

| White | 213.1 per 100,000 men | 149.8 per 100,000 women |

| African American | 276.6 per 100,000 men | 171.2 per 100,000 women |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 132.4 per 100,000 men | 92.1 per 100,000 women |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 191.0 per 100,000 men | 139.0 per 100,000 women |

| Hispanic | 152.1 per 100,000 men | 101.2 per 100,000 women |

NOTE: SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program.

SOURCE: NCI, 2013a.

lack of coordination of care was the greatest factor contributing to these differences (Ayanian et al., 2005).

Insurance status is also predictive of an individual’s chances of surviving cancer. Uninsured persons and persons enrolled in Medicaid are often diagnosed with cancer at a later stage than are individuals enrolled in other types of insurance (ACS, 2013b; Halpern et al., 2007). Those same individuals are less likely to survive cancer regardless of the stage at diagnosis (ACS, 2008). This difference in cancer outcomes can likely be explained by a number of factors, including these populations’ access to care, quality of cancer care, and health literacy. Uninsured and Medicaid enrollees are more likely than are other populations to face barriers in accessing care, such as the inability to find adequate transportation, to take time off from work, to pay out of pocket for the cost of care, or to find physicians who will accept Medicaid insurance or treat them without insurance. Conversely, individuals with private insurance are more likely to receive recommended, appropriate cancer screening and treatment than are individuals who have Medicare and Medicaid insurance, and who are racial and ethnic minorities, or have low SES (ACS, 2008; Harlan et al., 2005).

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN CANCER CARE

Medical knowledge has expanded in recent years and the pace of advancement is likely to accelerate. There have been breakthroughs in numerous areas of medical research, including genomics, stem cell biology, and molecular biology. This has led to the availability of many more diagnostic tests and treatments for cancer and has moved the practice of oncology toward more molecularly targeted medicine. These advancements, however, have coincided with unsustainable growth in health care spending—spending that is likely to be exacerbated in the future by a cancer care delivery system overwhelmed by many more patients and an increasingly complex patient population with multiple comorbidities. Congress, recognizing that national changes are needed to address these challenges, passed major health care reform legislation as well as a number of other policy initiatives in recent years. Each of these challenges and opportunities is discussed in detail below.

Trends in Cancer Treatment

Once the province of surgeons and local-regional therapies, cancer treatment has evolved rapidly in recent decades. Systemic treatments emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, initially as relatively nonspecific chemotherapies with limited efficacy in some human cancers. Empiricism,

rather than an understanding of tumor biology, dominated oncology drug development in this era. In recent years, researchers have developed treatments targeting specific molecular aberrations in cancer cells (e.g., Imatinib for chronic myelogenous leukemia, Trastuzumab for breast cancer). Molecularly targeted treatments have pervaded Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals in oncology in the past decade and have improved patient outcomes for many cancers. These agents commonly require a test to assess the drug target in the patient’s tumor. As such, companion diagnostic testing (e.g., estrogen receptor [ER] and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 [HER2] in breast cancer, anaplastic lymphoma kinase [ALK] and epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] in non-small-cell lung cancer) has increased in importance. The sheer number of targeted agents has increased the educational burden for cancer care clinicians and the financial burden for the health care system. In the near future, the implementation of genome-based diagnostics will likely alter both the ability to deliver precision medicine and the complexity of cancer treatment (IOM, 2010, 2012b; NRC, 2011).

Unique Considerations in Treating Older Adults with Cancer

There are a number of unique considerations in providing appropriate care to older adults with cancer. Older adults with cancer often have altered physiology, functional impairment (either at the time of diagnosis or as a potential consequence of treatment), multiple and often coexisting morbidities, increased side effects of treatment, and potentially different or additional treatment goals (Yancik, 1997). They may rely more heavily on social support to manage their disease than do younger individuals with cancer (see discussion on caregiving in Chapter 4). In addition, there are limited data from clinical trials to guide treatment decisions in older patients (see discussion in Chapter 5). Older patients—especially frail patients, those with organ dysfunction, or those with poor health status—are often excluded from cancer clinical trials, and the impact of cancer treatment on physical or cognitive function is typically not captured in clinical trials (Hutchins et al., 1999; Talarico et al., 2004; Unger et al., 2006; Yee et al., 2003). Stereotypes held by clinicians about older adults may also deter them from treating patients aggressively (Foster et al., 2010).

Older adults with cancer may have different treatment goals or preferences compared to younger patients with cancer. In a survey of older adults with chronic illness, for example, 74 percent of respondents did not want treatment if it would cause functional impairment, and 88 percent did not want treatment if it would cause cognitive impairment, regardless of the impact on survival (Fried et al., 2002). Clinicians’ treatment recommendations are greatly influenced by their patients’ age, comor-

bidity, and health status, and do not always take into account individual preferences (Hurria et al., 2008). Clinicians’ communication styles and their own treatment preferences also have an impact on the type of care older adults with cancer receive. In a study of patients 70 years and older with advanced colorectal cancer, patients’ preferences for an active or passive role in their chemotherapy decision making did not always match what their physician perceived as their preferred decision-making style (Elkin et al., 2007). Another study found that women who preferred less physician input were less likely to receive chemotherapy, while patients of oncologists who had a strong preference for providing chemotherapy were more likely to receive it (Mandelblatt et al., 2012). Decision aids, discussed in Chapter 3, are one mechanism that can help improve patients’ understanding of their prognosis, their treatment options, and the benefits and harms of treatment (Leighl et al., 2011).

A geriatric assessment is a useful tool for assessing the different needs of older adults. A geriatric assessment evaluates an older adult’s physiological changes, functional status, comorbid medical conditions, cognition, psychological status, social functioning and support, nutritional status, and polypharmacy. (See Box 2-1 for a description of each domain. Table 2-5 highlights the specific physiological changes that correlate with the aging process. However, it is important to recognize that clinical manifestations may not always be “typical” in an older adult.) Each of these domains is predictive of morbidity and mortality in the geriatric population (Inouye et al., 1998; Landi et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2006; Reuben et al., 1992; Rigler et al., 2002; Seeman et al., 1987; Studenski et al., 2004; Walter et al., 2001). Many of these domains are also predictive of prognosis in younger adults; however, they are particularly important for assessing older adults due to this population’s increased risk of social, physical, and mental vulnerability. Clinicians can use geriatric assessments to understand the unique needs of older adults with cancer and the potential benefits and harmsof various care plans (Extermann et al., 2012; Hurria et al., 2011a).

Unsustainable Cancer Care Costs

In the United States, the rising costs of health care is a central fiscal challenge (CBO, 2012b; IOM, 2012a; NRC, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2011). The United States spent $2.7 trillion on health care in 2011, accounting for 17.9 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) (CMS, 2013a). By 2037, health care costs are anticipated to account for almost 25 percent of the nation’s GDP (CBO, 2012a). Estimating future health care spending, however, is challenging, as it depends both on changes within the health care system and the economy as a whole (Fuchs, 2013). From 2015 to 2021,

BOX 2-1

Domains of a Geriatric Assessment

Physiological Changes

It is important for clinicians to recognize the potential for physiological decline in older adults with cancer when devising care plans for this population. The rate of decline and the appearance of resulting physiological consequences due to aging are unique to each individual. Age-related changes, including declines in organ function, can impact an individual’s tolerance for cancer therapy and the correct dosing of chemotherapy (Bajetta et al., 2005; Bruno et al., 2001; Crivellari et al., 2000; Extermann et al., 2012; Goldberg et al., 2006; Graham et al., 2000; Haller et al., 2005; Hurria et al., 2005, 2011b; Muss et al., 2007; Toffoli et al., 2001). Table 2-5 summarizes common age-related changes in various organ systems.

Periods of stress, such as stress induced by cancer and/or cancer treatment, can further impact an individual’s physiological state. For example, older adults often have increased bone marrow fat and decreased bone marrow reserve. In older adults with cancer, this is associated with an increased risk of myelosuppression (i.e., bone marrow suppression) and can lead to complications from chemotherapy, such as anemia and an increased distribution of drugs throughout the body (Dees et al., 2000; Gomez et al., 1998; Repetto et al., 2003).

Functional Status

Functional status is generally measured by assessing an individual’s ability to complete activities of daily living (ADLs) (e.g., grooming, dressing, eating, walking) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (e.g., shopping, housekeeping, accounting, preparing food, using the telephone, traveling). Cancer is associated with an increased need for assistance with these types of activities (Keating et al., 2005; Stafford and Cyr, 1997). It is important that the oncology workforce have tools to assess the functional status of older adults with cancer because this evaluation helps clinicians to determine a patient’s risk of treatment toxicity and postoperative complications; ascertain whether a patient receiving chemotherapy is able to seek medical attention if necessary (i.e., use the telephone to call for help, follow instructions, and anticipate and respond to toxicity); and estimate overall survival (Audisio et al., 2005; Extermann et al., 2012; Hurria et al., 2011a; Keating et al., 2005; Stafford and Cyr, 1997). For example, in a clinical trial of older patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer, pretreatment IADLs were correlated with survival (Maione et al., 2005). Other studies have shown that declines in physical function persisting over time are associated with poorer overall survival and increased risk of subsequent hospitalization, compared with declines in physical function that are transient (Mor et al., 1994; Sleiman et al., 2009). Measuring functional status at several points along the trajectory of illness may provide valuable prognostic information.

Comorbid Medical Conditions

It is important for the medical team to identify performance status and existing comorbidities in older adults with cancer, because these can impact a patient’s prognosis and tolerance for cancer treatment (Birim et al., 2006; Frasci et al., 2000; Steyerberg et al., 2006). The presence of multiple comorbidities is associated with worse survival in adults with cancer (Extermann et al., 2000; Firat et al., 2002; Frasci et al., 2000; Piccirillo et al., 2004; Satariano and Ragland, 1994). Individuals with multiple comorbidities are also likely to experience a decline in functional status over time (Rigler et al., 2002; Studenski et al., 2004). However, further research is needed to understand the longitudinal relationship between comorbidities and subsequent functional status of older adults with cancer (Dacal et al., 2006; Extermann et al., 1998; Hurria et al., 2006; Yancik et al., 2007).

Nutritional Status

Few studies have examined the association between cancer, aging, and nutrition, but existing evidence suggests that nutritional status may have an impact on prognosis and survival. For example, older adults are at an increased risk for mucositis, which impacts an individual’s ability to maintain adequate nutrition during cancer therapy. Weight loss in cancer patients is associated with poorer chemotherapy response rates and poorer survival (Dewys et al., 1980). There is also evidence that poor nutritional status is associated with an increased risk of mortality (Landi et al., 2000). In a study of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, severe malnutrition was associated with greater toxicity and reduced overall survival (Barret et al., 2011).

Cognition

A cognitive assessment in older adults with cancer should be conducted to determine whether a patient has the ability to consent to and adhere to medication regimens in the home. Both aging and cancer therapy have the potential to impact cognitive function. A patient with cognitive impairment will likely need assistance from a family member, friend, or caregiver to maintain safety and remember instructions on taking medications. There is also an association between cognitive function and physical function, so a patient with cognitive impairment may also require assistance with other ADLs/IADLs (Dodge et al., 2005; Sauvaget et al., 2002; Wadley et al., 2008).

Psychological State and Social Support

Many older adults with cancer are at risk for depression, psychological distress, and social isolation. Depression is common in older adults and can be hard

to diagnose because the symptoms of cancer and depression often overlap, and the presentation of depression in older adults is often more somatic and less affective or emotional than in younger persons (Weinberger et al., 2009). However, it is important to identify and treat depression in older adults because depressive symptoms are associated with a decline in physical function (Penninx et al., 1998). Similarly, in a recent study, 41 percent of older adults with cancer reported psychological distress, which was correlated with poorer physical function (Hurria et al., 2009). Evidence from both the geriatric and the oncology literature has linked social isolation to a higher risk of death (Kroenke et al., 2006; Reuben et al., 1992; Seeman et al., 1993; Waxler-Morrison et al., 1991). For example, two studies have found that women with breast cancer who get divorced or separated and lack adequate social support are at a higher risk for severe psychological distress (Kornblith et al., 2001, 2003). Social support plays a vital role in the psychological functioning of older adults and can mitigate the psychological impact of stressful life events, such as a cancer diagnosis and cancer treatment (Kornblith et al., 2001). Thus, assessing a patient’s psychological state and their social support system can provide important prognostic information.

Polypharmacy

Older adults are likely to have one or more chronic conditions and, as a result, see multiple clinicians and take multiple medications (Gurwitz, 2004; Hajjar et al., 2007; Hanlon et al., 2001; Safran et al., 2005). It is important for clinicians to assess the medications older adults receive in addition to cancer therapy, because the use of multiple medications increases an individual’s risk of adverse effects. Drug-drug and drug-disease interactions, for example, can lead to increased or decreased clinical effects, increased drug toxicity, and compromised adherence to therapy (Elmer et al., 2007; Qato et al., 2008; Riechelmann and Del Giglio, 2009). There is also the risk of medication duplication (where medications of the same or similar drug class or therapeutic effect taken concurrently do not provide any additional benefit) and medication underuse (where patients are overwhelmed by the number of medications they have been prescribed and do not take some of them). This assessment should consider dosage and indications of prescription medications, as well as over-the-counter, herbals, and complementary/alternative medications (Qato et al., 2008; Rolita and Freedman, 2008; Yoon and Schaffer, 2006). Evidence suggests that having a pharmacist or interdisciplinary team review a patient’s medications can lessen the number of medications a patient must take or identify potential drug-drug interactions (Bregnhoj et al., 2009; Chrischilles et al., 2004; Crotty et al., 2004; Davis et al., 2007; Hanlon et al., 1996; Holmes et al., 2008; Spinewine et al., 2007; Stuijt et al., 2008; Vinks et al., 2009). Clinicians’ use of electronic drug databases and indexes on appropriate medication can also help identify unnecessary medications or potential drug-drug interactions (Clauson et al., 2007; Egger et al., 2003; Tulner et al., 2008; Weber et al., 2008). Methods to help clinicians assess the appropriateness of drug prescribing have also been developed, including the Medication Appropriateness Index and the Beers Criteria (Beers, 1997; Beers et al., 1991; Fick et al., 2003; Hanlon et al., 1992; Zhan et al., 2001).

TABLE 2-5 Examples of Age-Related Changes in Each Organ of the Functional System

| System or Function | Age-Related Changes |

| Cardiovascular system |

• Decreased maximal heart rate in response to stress • Increased wall stiffness that leads to reduction in early diastolic filling and diastolic dysfunction • Declined ventricular function |

| Gastrointestinal system |

• Decreased secretion of digestive enzymes • Changed peristalsis rate; gastric emptying is prolonged • Decreased basal gastric flow • Changed intestinal motility and absorption • Decreased liver size, volume, and blood flow |

| Pulmonary system |

• Declined lung recoil • Decreased ability to clear secretions • Increased airway resistance |

| Renal function |

• Decreased kidney weight • Decreased renal blood flow • Decreased creatinine clearance • Decreased reabsorption and responsiveness to regulatory hormones |

| Neurologic system |

• Decreased hearing/eyesight • Increased response time • Increased risk of developing delirium • Increased risk of peripheral neuropathy |

| Hematologic system |

• Decreased bone marrow reserve • Increased risk of infection and anemia |

| Immunologic changes |

• Increased susceptibility to infection • Altered T-cell function |

| Changes in body composition may lead to alterations in drug distribution |

• Increased body fat • Decreased lean body mass • Decreased total body water • Increased susceptibility to dehydration |

SOURCES: Avorn and Gurwitz, 1997; Baker and Grochow, 1997; Duthie, 2004; Sawhney et al., 2005; Sehl et al., 2005; Vestal, 1997; Yuen, 1990.

the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has estimated that health care spending will grow at an average rate of 6.2 percent annually, driven by a number of factors, including the aging of the population and implementation of health care reform (CMS, 2013b). Likewise, although the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently revised its 10-year projection of Medicaid and Medicare spending downward by 3.5 percent, it has projected an increase in federal deficits due to the pressures of an

aging population, rising health care costs, expansion of federal subsidies for health insurance as part of health care reform, and growing interest payments on federal debt (CBO, 2013a,b,c). The growth in health care spending has slowed in recent years but it is unclear that this trend will continue (Fuchs, 2013; Hartman et al., 2013; Ryu et al., 2013). Regardless, health economist Victor Fuchs (2013) has asserted that national health care spending will continue to pose challenges for the U.S. economy in the future.

Health care costs are a critical challenge to the nation’s economic stability. In 2009, health care spending in the United States was 2.5 times greater than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average (OECD, 2013). Rising health care costs could lead to higher taxes, a decline in the nation’s GDP, decreased employment, and a lower standard of living (AHR, 2012; Baicker and Skinner, 2011). They could also threaten the United States’ economic competitiveness and perpetuate the stagnation of employee wages seen in the past 30 years (Emanuel and Fuchs, 2008). In addition, increased spending on health care diverts spending from a number of other national priorities, including investments in education, infrastructure, and research (BPC, 2012; Emanuel et al., 2012; Milstein, 2012). Fuchs has said that if the United States solves its health care spending problem, “practically all of our fiscal problems go away. [And if we don’t], then almost anything else we do will not solve our fiscal problems” (Kolata, 2012).

Cancer care costs make a substantial contribution to rising health care costs. The costs of direct medical care for cancer are estimated to account for 5 percent of national health care spending (Sullivan et al., 2011); however, one large insurer, UnitedHealthcare, estimated that 11 percent of its costs are for cancer care (IOM, 2013). National expenditures for cancer care accounted for $72 billion in 2004, rose to $125 billion in 2010, and are likely to increase to $158 billion in 2020 due to demographic changes alone (Mariotto et al., 2011; NCI, 2007). Accounting for the rise in cancer care costs, researchers estimated that costs could reach $173 billion in 2020, a 39 percent increase from 2010 (Mariotto et al., 2011). Cancer care costs are growing faster than are costs for other sectors of medicine (Bach, 2009; Elkin and Bach, 2010; Meropol and Schulman, 2007; Yabroff et al., 2011). In fact, Sullivan et al. (2011) suggested that increases in the costs of cancer care could begin to outpace health care inflation as a whole and account for a greater share of total health care spending.

A number of factors influence the cost of cancer care. The overall growth in spending on cancer care is related to both the increased price of cancer care and quantity of cancer care (Bach, 2009; Elkin and Bach, 2010). Cancer care costs are highest in the months following a cancer diagnosis and at the end of life (Yabroff et al., 2011). As more expensive targeted

treatments and other new technologies become the standard of care in the near future, the costs of cancer care are projected to escalate rapidly. An editorial from leaders in the cancer community concluded that some of these new treatments are “rightly heralded as substantial advances, but others provide only marginal benefit” (Emanuel et al., 2013). The FDA approved 13 new cancer treatments in 2012; of these, only 1 extended survival by more than a median of 6 months, 2 extended survival for only 4 to 6 weeks, and all cost more than $5,900 per month of treatment (Emanuel et al., 2013).

Drug manufacturers may be facing more pressure to moderate their prices for cancer treatments (Bach et al., 2012; Kantarjian and experts in chronic myeloid leukemia, 2013). For example, Zaltrap (ziv-aflibercept), approved for colorectal cancer treatment, was initially priced at $11,000 per month of treatment, more than twice as much as for the usual dose of a medicine with similar patient outcomes. Pushback from a cancer center prompted Sanofi to provide hospitals and clinicians with a 50 percent discount on the price of Zaltrap (Pollack, 2012). However, patients and payers were still required to cover the full amount of the drug during its initial months on the market. These parties will only benefit from Sanofi’s discount once Medicare’s average sales price reflects the actual cost of the drug (Conti, 2012). (See Box 8-2 for a more detailed discussion of how Medicare Part B drugs are reimbursed.) Based on a recent estimate, the price of Zaltrap has dropped by almost half since it was marketed but is still more expensive than comparable drugs (Goldberg, 2013).

The FDA approves cancer drugs based on its evaluation of their safety and efficacy, but it does not consider issues of cost or effectiveness in its decisions (The Lewin Group, Inc., 2007). Drug compendia, such as the one produced by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, often guide the use of off-label prescribing for cancer treatments, though the information in the compendia is of variable quality and often not adequate to support these decisions (Abernethy et al., 2009, 2010). Additional drivers of costs include the current deficiencies in the cancer care delivery system and payment models (see discussion in Chapter 8); diffusion of innovations in clinical practice with variable and often insufficient evidence supporting their use (see Chapter 5); patient and clinician attitudes, beliefs, and practices (see Chapter 3); and legal and regulatory challenges (see Chapter 8).

The consolidation of private oncology practices into hospital-based practices is also driving up cancer care costs (Guidi, 2013; IOM, 2013). Hospitals are able to negotiate with payers to receive higher reimbursement for oncology services than private medical practices because they have more leverage. Hospitals provide many essential services that private medical practices do not offer (such as bed access). Hospitals use

this leverage to their advantage when negotiating their charges and link the provision of these essential services with better reimbursement for oncology care (IOM, 2013). In addition, hospital costs are likely to have an increasingly large impact on the total cost of cancer care in the near future, as patients are receiving a greater proportion of their cancer care in hospital outpatient settings (Guidi, 2013).

Health Reform, HITECH, and Other Policy Initiatives

In the past decade, Congress has passed major legislation to improve care for people with cancer: in particular, the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, also known as the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) (2003), the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act (2009), and the ACA (2010) (see discussions on the MMA in Chapter 8 and the HITECH Act in Chapter 6). These laws and other regulatory changes will impact many aspects of cancer care, including access, delivery systems, quality improvement efforts, research infrastructure, and payment and reimbursement.

This section focuses on the impact of the ACA on cancer care and outlines how the changing policy landscape will likely impact cancer patients and survivors. Signed into law in 2010 and upheld in large part by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2012, the ACA is the most substantial piece of health care legislation enacted since Medicare in 1965. Annex 2-1 provides a summary of the ACA provisions most relevant to cancer care.

Expanding Insurance Coverage

One of the ACA’s primary goals is to expand insurance coverage to reduce the number of uninsured individuals. Beginning in 2014, nearly all U.S. citizens will be required to have health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. To ensure that individuals are able to obtain the mandated coverage, the ACA provides subsidies for some individuals and creates market reforms to foster increased access to private and public coverage for others.

The ACA offers states the ability to expand public insurance coverage by removing the Medicaid eligibility categories and raising the income threshold. Now, states can choose to allow all non-elderly, non-disabled citizens, and legal U.S. residents with family incomes below 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), or about $30,000 per year for a family of four, to be eligible for Medicaid benefits. Primarily, this extends coverage to low-income, childless adults, providing them with access to preventive care such as colon and breast cancer screenings, among other services.

By expanding the reach of public insurance, it is anticipated that more

people with cancer can be diagnosed and treated at an earlier stage, thus increasing their chance for survival. However, the Medicaid expansion may not reach as far as initially expected. Following the Supreme Court’s decision in June 2012, states have been encouraged, but not required, to expand their Medicaid programs. As of June 2013, 23 states and the District of Columbia plan to expand their Medicaid programs, 6 states are undecided, and 21 are not expanding their Medicaid program at this time (KFF, 2013c). Individuals living in states that do not expand Medicaid will likely turn to the Health Insurance Marketplace for additional coverage or remain uninsured.

The ACA also expands insurance coverage by creating a “one stop shop” for insurance called the Health Insurance Marketplace (formerly, the “Exchange”). States can (1) administer their own, state-based marketplace (17 states); (2) work with the federal government in a partnership (7 states); or (3) default to the federally facilitated Health Insurance Marketplace (21 states) (KFF, 2013d; numbers current as of May 2013). Regardless of the administration, marketplaces will offer multiple tiers of “qualified health plans” for individuals and small businesses to purchase health insurance. To further encourage purchase of an insurance plan, the federal government will provide subsidies for low-income individuals and families (between 100 to 400 percent of the FPL) to help cover premium costs. Until the marketplaces are up and running, temporary high-risk pools offer coverage to those who have been uninsured for at least the previous 6 months due to a preexisting condition, such as cancer; in 2014, these beneficiaries will transition into marketplace-sponsored coverage.

Because young adults are much more likely to be un- or underinsured, the ACA expands their access to coverage by requiring that most private insurers provide young adults with the option to remain on their parents’ insurance plans until age 26. Notably, although cancer death rates have declined in all other age groups during the past decade, individuals ages 15 to 29 have not seen decreases in cancer death rates and individuals ages 25 to 29 have seen increases in cancer death rates (Bleyer et al., 2012). In addition, adolescents and young adults have not had comparable gains in 5-year cancer survival compared to younger and older age groups (NCI, 2013b). Although the reasons for this lack of progress are complex and not well understood, they may be due in part to a lack of health insurance and delays in diagnosis (Bleyer et al., 2012; NCI, 2013b). By extending dependent coverage to as many as 3 million young adults and expanding health insurance coverage through Medicaid expansions and the Health Insurance Marketplace, the ACA may improve access to cancer care for the estimated 68,400 adolescents and young adults ages 15 to 39 who are diagnosed with cancer each year (Bleyer et al., 2012; NCI, 2013b; Sommers et al., 2013).

Protecting Consumers and Improving the Quality of Care

In addition to improving health insurance coverage, the ACA protects consumers by mandating changes to the health care system intended to make health insurance more affordable, comprehensive, and widely available, regardless of a person’s health status.

The law prohibits common practices used to restrict eligibility, like denying coverage or charging higher premiums for preexisting conditions such as cancer. Historically, such practices have made it difficult, if not impossible, for many cancer survivors to gain meaningful health insurance coverage. Requiring insurers to accept all applicants, regardless of their preexisting condition, is a major improvement for ensuring patients’ access to cancer care.

In the past, patients with expensive cancer treatments could quickly reach their annual and lifetime health care coverage limits, placing them at financial risk for covering the cost of potentially lifesaving care. To address this problem, the ACA prohibits many health plans from placing lifetime limits on benefits for specific conditions and restricts the extent to which plans can place annual limits on coverage. Such a change provides important protections for cancer patients and survivors who will no longer have to worry about their coverage being dropped or limits on coverage being applied.

The ACA sets a baseline for necessary services, with the goal of providing meaningful and comprehensive coverage for certain health plans. Qualified health plans will offer coverage in the new marketplaces and will be required to offer a basic level of care, known as the essential health benefits (EHB) package, although the federal government has given states flexibility in determining which health benefits to designate as “essential.” The EHB is designed to reflect what “typical employer coverage” provides across 10 broad categories:

1. ambulatory patient services;

2. emergency services;

3. hospitalization;

4. maternity and newborn care;

5. mental health and substance use disorder services (including behavioral health);

6. prescription drugs;

7. rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices;

8. laboratory services;

9. prevention and wellness services and chronic disease management; and

10. pediatric services including oral and vision care.

Also notable for cancer patients are several ACA provisions related to clinical trials. Starting in 2014, many insurers must cover the routine medical costs of patients participating in clinical trials (i.e., costs that would have otherwise been covered if the patient were not involved in the trial). In addition, insurers will no longer be able to deny coverage to individuals participating in cancer clinical trials.

The ACA also increases the health care system’s emphasis on prevention. U.S. residents only receive half of recommended preventive care, but it is estimated that more frequent use of these services could save the United States more than 2 million life-years annually (Maciosek et al., 2010). As a result of the ACA, most health plans must cover certain preventive services, like mammography screening, without cost sharing. This includes services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), immunization schedules endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, and benefits for women and children suggested by the Health Resources and Services Administration.3 Many, if not all, of the recommended services will also be available to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. States will be eligible for increased Federal Medical Assistance Percentages (also referred to as federal matching funds, or FMAP) if their Medicaid program offers more optional preventive services (those classified as A or B by USPSTF) without cost sharing. A focus on prevention is essential for those at risk for cancer, not only because of increased access to screening and diagnosis but also because emphasis on concepts such as healthy eating, physical activity, and smoking cessation help to reduce risk factors for a wide variety of chronic diseases, including cancer.

Transforming Delivery Systems

In cancer care, a wide variety of treatment options is often available. Individuals’ biological characteristics, personal preferences, and clinician recommendations should influence their treatment decisions. The goal of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, established by the ACA, is to provide clinicians and patients with evidence-based research to help them make more informed health care decisions (PCORI, 2013).

As a part of the ACA, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) created a National Strategy for Quality Improvement in Health Care (“National Quality Strategy”) to support national, state, and local efforts to improve health care quality. The National Quality Strategy

____________________

3Federal Register. 2010a. Interim final rules for group health plans and health insurance issuers relating to coverage of preventive services under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Federal Register 75(127):41726-41730.

encourages better care, with a focus on patient-centeredness, reliability, accessibility, and safety while also calling for attention to population health and affordability of care.

Controlling Rising Health Care Costs

The overall aim of the ACA is to make health insurance more available and affordable to Americans. While these efforts ultimately aim to reduce the cost of health care in this country, other provisions of the law focus more directly on cost-saving measures. For example, the ACA created the CMS Innovation Center to allow states and other stakeholders to test new ways to improve the health of their communities, with the ultimate goal of improving patient outcomes while reducing costs. The CMS Innovation Center is evaluating a number of delivery system and payment models, including accountable care organizations, patient-centered medical homes, and bundled payments (see Chapter 8).

This section briefly provides an overview of the major stakeholders involved in the cancer care delivery system. Improving the quality of cancer care requires coordination and commitment from all of these parties.

Patients, Families, and Family Caregivers

As mentioned above, there are approximately 14 million people in the United States with a history of cancer, and more than 1.6 million people are newly diagnosed with cancer each year (ACS, 2012c). These individuals, including their family members and caregivers, are the central focus of the cancer care delivery system. There are many nonprofit organizations that work to ensure that patients’ cancer needs are met by educating patients, improving quality of care and access to care, promoting beneficial public policy, and providing financial support for research. The importance of patient-centered communication and shared decision making in cancer care is discussed in Chapter 3. The role of family caregivers is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

Health Care Clinicians

Many different professionals participate in cancer care, including medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, surgeons, primary care clinicians, geriatricians, nurses, advanced practice registered nurses, physician assistants, psychosocial workers, pharmacists, rehabilitation clinicians,

spiritual workers, and other professionals. Ideally, these health care clinicians work together to provide patients with coordinated care across the cancer continuum. Most of these professionals are represented by organizations that work to further the interests of their members, and many of these professional societies conduct ongoing efforts designed to monitor, measure, and improve the quality of cancer care. In addition, these organizations are often involved in developing clinical practice guidelines, which provide members with guidance on the best treatment options and can be used to develop clinician and hospital quality measures. The role of the workforce providing care to patients with cancer in improving the quality of cancer care is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4. The role of professional organizations in developing a learning health care system is discussed in Chapter 6. The role of professional organizations in developing clinical practice guidelines and quality metrics is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Payers

CMS is the federal agency that manages Medicare, the major insurer of U.S. adults over the age of 65. It currently insures more than 49 million Americans. As the second largest payer for cancer care behind private insurers, Medicare has a great deal of influence on the quality of cancer care in the United States (Tangka et al., 2010). This influence will only continue to expand: by 2030, Medicare will cover an estimated 70 percent of Americans who have cancer (reviewed in AHRQ, 2011a). Medicare provides beneficiaries with protection against the cost of many health care services, including inpatient hospital stays, skilled nursing facility stays, home health visits, hospice care, physician visits, outpatient services, and preventive services. It also includes a voluntary prescription drug benefit. Some limitations of the coverage, however, include relatively high deductibles, no limit on out-of-pocket spending, and no coverage for long-term care or dental services. Many beneficiaries have supplemental insurance to cover these gaps in coverage and high cost-sharing requirements (KFF, 2012). However, like Medicare, supplemental coverage can also come with high premiums or cost-sharing requirements, and thus, many low-income Medicare beneficiaries may be unable to acquire additional coverage.

CMS also funds Medicaid jointly with the states. It is the largest health insurance program and the dominant payer of long-term care in the United States. Medicaid currently covers more than 62 million Americans and will undergo massive expansion with the implementation of the ACA in 2014. Medicaid covers primarily low-income individuals and families, as well as individuals living with disabilities and complex health

care needs. Medicaid also provides supplemental coverage to many older adults, as some individuals are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid coverage (KFF, 2013a). Because Medicaid covers such a substantial portion of the U.S. population at disproportionate risk for cancer, it is likely one of the primary payers for cancer care.

The role of payers in improving the accessibility and affordability of cancer care is discussed in more detail in Chapters 3 and 8.

Government Organizations

In the United States, the federal government conducts a number of activities related to improving the quality of cancer care, including programs designed to fund research, conduct public health initiatives, improve patient safety, ensure an adequate health care workforce, and disseminate health information (see Table 2-6). The role of many federal agencies in cancer research is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5. The roles of many other agencies in improving the quality of cancer care are discussed throughout the report (e.g., CMS in the previous section).

Health Information Technology Organizations

Health information technology (health IT), such as electronic health records, plays an important role in advancing cancer care. Multiple organizations, including the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, the National Cancer Institute, and CMS, participate in health IT activities that support the effective and meaningful use of such technologies. These organizations are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

Organizations Involved in Cancer Care Quality Measurement

A number of organizations track and evaluate the performance of health care clinicians, practices, and hospitals by comparing actual clinical practices to recommended practice. Recommended practices are established based on the best available evidence and existing clinical practice guidelines. In many cases, however, there is little evidence and no relevant clinical practice guidelines to support the recommended practices. This has been a substantial barrier to the development of performance measures (IOM, 2008). These organizations are discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

TABLE 2-6 Examples of U.S. Governmental Organizations Involved in Improving Quality of Cancer Care

| Organization | Description |

| AHRQ | The branch of HHS focused on the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of health care. It funds research that helps people make more informed health care decisions and improves the quality of health care services. Its focus areas are: encouraging the use of evidence to inform health care decisions, fostering patient safety and quality improvement, and encouraging efficiency by increasing access to effective health care and reducing unnecessary costs. |

| CDC | The branch of HHS focused on promoting health; preventing disease, injury, and disability; and preparing for new and emerging health threats. The mission of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control (DCPC) is to prevent and control cancer. DCPC works with various groups at the national and state levels to collect data on cancer incidence, mortality, risk factors, and cancer screening; conduct and support research and evaluation; build capacity and partnerships; and educate clinicians, policy makers, and the public. Examples of DCPC programs include the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program, the National Program of Cancer Registries, and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program. |

| CMS | The federal agency that manages Medicare, the major insurer of U.S. adults over the age of 65. It currently insures over 49 million Americans (see discussion in the section on payers). It also funds Medicaid jointly with the states. Medicaid is run by the states to provide health insurance coverage to individuals with lower incomes. |

| FDA | The regulatory agency that ensures the safety, efficacy, and security of drugs, biological products, and medical devices. The FDA’s Office of Hematology and Oncology Products oversees the development, approval, and regulation of drug and biologic treatments for cancer, therapies for cancer prevention, and products for treatment of nonmalignant hematologic conditions. The FDA’s Cancer Liaison Program brings the patient advocate’s perspective into the evaluation of new cancer drugs and meets with patient advocacy groups to learn their viewpoints and address their concerns regarding cancer drug development. |

| Organization | Description |

| HRSA | The federal agency charged with improving access to health care services for people who are uninsured, vulnerable, or underserved. HRSA offers training and financial support to clinicians caring for these populations. HRSA coordinates the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, which collects workforce data, develops tools for projecting workforce supply and demand, and evaluates workforce policies and programs. HRSA also administers the National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships and loan repayment to primary care clinicians practicing in areas with workforce shortages. |

| NCI | The section of NIH responsible for cancer research and training. The NCI coordinates the National Cancer Program, which conducts research, training, and the dissemination of information on cancer. The NCI supports cancer research conducted at universities, foundations, hospitals, and businesses through grants and cooperative agreements; conducts its own research; provides career awards, training grants, and fellowships for basic and clinical research and treatment programs; supports a national network of cancer centers; and supports cancer research infrastructure through construction grants. |

| NIA | The section of NIH that supports research on the aging process and diseases and conditions associated with growing older. NIA supports the development of research and clinician scientists in aging and disseminates information about aging to the public, health professionals, and the scientific community. |

NOTE: AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CDC = Centers for Disease and Control Prevention; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

SOURCES: AHRQ, 2012a; CDC, 2010, 2011; CMS, 2012; FDA, 2012a,b,c; HRSA, 2012, 2013a,b; NCI, 2012b; NIA, 2012.

AACR (American Association for Cancer Research). 2012. AACR cancer progress report 2012: Making research count for patients: A new day. Philadelphia, PA: American Association for Cancer Resarch.

Abernethy, A. P., G. Raman, E. M. Balk, J. M. Hammond, L. A. Orlando, J. L. Wheeler, J. Lau, and D. C. McCrory. 2009. Systematic review: Reliability of compendia methods for off-label oncology indications. Annals of Internal Medicine 150(5):336-343.

Abernethy, A. P., R. R. Coeytaux, K. Carson, D. McCrory, S. Y. Barbour, M. Gradison, R. J. Irvine, and J. L. Wheeler. 2010. Report on the evidence regarding off-label indications for targeted therapies used in cancer treatment: Technology assessment report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

ACS (American Cancer Society). 2008. Cancer facts and figures 2008. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

———. 2011. Cancer facts & figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

———. 2012a. Cancer facts & figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2012-2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

———. 2012b. Cancer facts & figures 2012. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

———. 2012c. Cancer treatment and survivorship: Facts and figures 2012-2013. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

———. 2013a. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2013-2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

———. 2013b. Cancer facts & figures 2013. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

ACSCAN (American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network). 2009. Cancer disparities: A chartbook. Washington, DC: American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network.

AHR (Alliance for Health Reform). 2012. High and rising costs of health care in the U.S. The challenge: Changing the trajectory. http://www.allhealth.org/publications/Alliance_for_Health_Reform_121.pdf (accessed March 12, 2013).

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2011a. Utilization and cost of anticancer biologic products among Medicare beneficiaries, 2006-2009. Anticancer biologics. Data Points #6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65148/pdf/dp6.pdf (accessed March 24, 2013).

———. 2011b. National healthcare disparities report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

———. 2012a. AHRQ at a glance. http://www.ahrq.gov/about/mission/glance/index.html (accessed June 26, 2013).

———. 2012b. National healthcare dispartities report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Andriole, G. L., E. D. Crawford, R. L. Grubb, 3rd, S. S. Buys, D. Chia, T. R. Church, M. N. Fouad, C. Isaacs, P. A. Kvale, D. J. Reding, J. L. Weissfeld, L. A. Yokochi, B. O’Brien, L. R. Ragard, J. D. Clapp, J. M. Rathmell, T. L. Riley, A. W. Hsing, G. Izmirlian, P. F. Pinsky, B. S. Kramer, A. B. Miller, J. K. Gohagan, and P. C. Prorok. 2012. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: Mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 104(2):125-132.

Audisio, R. A., H. Ramesh, W. E. Longo, A. P. Zbar, and D. Pope. 2005. Preoperative assessment of surgical risk in oncogeriatric patients. Oncologist 10(4):262-268.

Avorn, J., and H. H. Gurwitz. 1997. Principles of pharmacology. In Geriatric Medicine, 3rd ed., edited by C. K. Cassel, H. J. Cohen, E. B. Larson and D. E. Meier. New York: Springer. Pp. 55-70.

Ayanian, J., A. Zaslavsky, E. Guadagnoli, C. Fuchs, K. Yost, C. Creech, R. Cress, L. O’Connor, D. West, and W. Wright. 2005. Patients’ perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23(27):6576-6586.

Bach, P. B. 2009. Limits on Medicare’s ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. New England Journal of Medicine 360(6):626-633.

Bach, P. B., L. B. Saltz, and R. E. Wittes. 2012. In cancer care, cost matters. New York Times, October 15, 2012, A25.

Baicker, K., and J. S. Skinner. 2011. Health care spending growth and the future of U.S. tax rates. http://www.nber.org/papers/w16772 (accessed March 12, 2013).

Bajetta, E., G. Procopio, L. Celio, L. Gattinoni, S. Della Torre, L. Mariani, L. Catena, R. Ricotta, R. Longarini, N. Zilembo, and R. Buzzoni. 2005. Safety and efficacy of two different doses of Capecitabine in the treatment of advanced breast cancer in older women. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23(10):2155-2161.

Baker, S. D., and L. B. Grochow. 1997. Pharmacology of cancer chemotherapy in the older person. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 13(1):169-183.

Barret, M., D. Malka, T. Aparicio, C. Dalban, C. Locher, J. M. Sabate, S. Louafi, T. Mansourbakht, F. Bonnetain, A. Attar, and J. Taieb. 2011. Nutritional status affects treatment tolerability and survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: Results of an AGEO prospective multicenter study. Oncology 81(5-6):395-402.

Beers, M. H. 1997. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. An update. Archives of Internal Medicine 157(14):1531-1536.

Beers, M. H., J. G. Ouslander, I. Rollingher, D. B. Reuben, J. Brooks, and J. C. Beck. 1991. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine 151(9):1825-1832.

Birim, O., A. P. Kappetein, R. J. van Klaveren, and A. J. Bogers. 2006. Prognostic factors in non-small cell lung cancer surgery. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 32(1):12-23.

Bleyer, A., C. Ulrich, and S. Martin. 2012. Young adults, cancer, health insurance, socioeconomic status, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Cancer 118(24): 6018-6021.

Booth, C. M., G. Li, J. Zhang-Salomons, and W. J. Mackillop. 2010. The impact of socioeconomic status on stage of cancer at diagnosis and survival. Cancer 116(17):4160-4167.

BPC (Bipartisan Policy Center). 2012. What is driving U.S. health care spending? http://bipartisanpolicy.org/sites/default/files/BPC%20Health%20Care%20Cost%20Drivers%20Brief%20Sept%202012.pdf (accessed December 16, 2012).

Bregnhoj, L., S. Thirstrup, M. B. Kristensen, L. Bjerrum, and J. Sonne. 2009. Combined intervention programme reduces inappropriate prescribing in elderly patients exposed to polypharmacy in primary care. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 65(2):199-207.

Bruno, R., N. Vivier, C. Veyrat-Follet, G. Montay, and G. R. Rhodes. 2001. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for docetaxel. Investigational New Drugs 19(2):163-169..

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2012a. The 2012 long-term budget outlook. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/06-05-Long-Term_Budget_Outlook_2.pdf (accessed December 14, 2012).

———. 2012b. Health care. https://cbo.gov/topics/health-care (accessed December 16, 2012).

———. 2013a. The budget and economic outlook: Fiscal years 2013 to 2023. Publication Number 4649. https://cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43907-BudgetOutlook.pdf (accessed March 12, 2013).

———. 2013b. How have CBO’s projections of spending for Medicare and Medicaid changed since the August 2012 baseline? http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43947 (accessed June 25, 2013).

———. 2013c. The budget and economic outlook: Fiscal years 2013 to 2023. http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43907 (accessed June 25, 2013).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2010. Vision, mission, core values, and pledge. http://www.cdc.gov/about/organization/mission.htm (accessed June 26, 2013).

———. 2011. About CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/about/ (accessed June 27, 2013).

———. 2012a. Cancer among men. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/men.htm (accessed August 7, 2012).

———. 2012b. Cancer among women. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/women.htm (accessed August 7, 2012).

———. 2013. Adult cigarette smoking in the United States: Current estimate. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking (accessed June 7, 2013).

Chrischilles, E. A., B. L. Carter, B. C. Lund, L. M. Rubenstein, S. S. Chen-Hardee, M. D. Voelker, T. R. Park, and A. K. Kuehl. 2004. Evaluation of the Iowa Medicaid Pharmaceutical Case Management Program. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association 44(3):337-349.

Clauson, K. A., W. A. Marsh, H. H. Polen, M. J. Seamon, and B. I. Ortiz. 2007. Clinical decision support tools: Analysis of online drug information databases. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 7:7.

Clegg, L. X., M. E. Reichman, B. A. Miller, B. F. Hankey, G. K. Singh, Y. D. Lin, M. T. Goodman, C. F. Lynch, S. M. Schwartz, V. W. Chen, L. Bernstein, S. L. Gomez, J. J. Graff, C. C. Lin, N. J. Johnson, and B. K. Edwards. 2009. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: Selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes and Control 20(4):417-435.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2012. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). http://www.cms.gov (accessed April 26, 2012).

———. 2013a. National health expenditure data. Historical. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html (accessed March 12, 2013).

———. 2013b. National health expenditure data. Projected. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected.html (accessed March 12, 2013).

Conti, R. 2012. Zaltrap economics 101: The pricing and repricing of an expensive drug. Cancer Letter 38(43):1-4.

Crivellari, D., M. Bonetti, M. Castiglione-Gertsch, R. D. Gelber, C. M. Rudenstam, B. Thürlimann, K. N. Price, A. S. Coates, C. Hürny, J. Bernhard, J. Lindtner, J. Collins, H. J. Senn, F. Cavalli, J. Forbes, A. Gudgeon, E. Simoncini, H. Cortes-Funes, A. Veronesi, M. Fey, and A. Goldhirsch. 2000. Burdens and benefits of adjuvant Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate, and Fluorouracil and Tamoxifen for elderly patients with breast cancer: The International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial VII. Journal of Clinical Oncology 18(7):1412-1422.

Crotty, M., D. Rowett, L. Spurling, L. C. Giles, and P. A. Phillips. 2004. Does the addition of a pharmacist transition coordinator improve evidence-based medication management and health outcomes in older adults moving from the hospital to a long-term care facility? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy 2(4):257-264.

Dacal, K., S. M. Sereika, and S. L. Greenspan. 2006. Quality of life in prostate cancer patients taking androgen deprivation therapy. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 54(1):85-90.

Davis, R. G., C. A. Hepfinger, K. A. Sauer, and M. S. Wilhardt. 2007. Retrospective evaluation of medication appropriateness and clinical pharmacist drug therapy recommendations for home-based primary care veterans. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy 5(1):40-47.

de Moor, J. S., A. B. Mariotto, C. Parry, C. M. Alfano, L. Padgett, E. E. Kent, L. Forsythe, S. Scoppa, M. Hachey, and J. H. Rowland. 2013. Cancer survivors in the United States: Prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 22(4):561-570.