This chapter provides information about the Global Nuclear Detection Architecture (GNDA). The first section describes the GNDA: specifically, what it is and who its partners are. The second section describes the challenges to evaluating its effectiveness.

2.1 GNDA DESCRIPTION

The committee spent a considerable amount of time understanding the design and structure of the GNDA. To the committee’s knowledge there is no single document that provides a detailed description of the functions, requirements, and design of the GNDA. However, the GNDA Strategic Plan (GNDA, 2010) and Joint Annual Interagency Review (GNDA, 2011, 2012) do provide general descriptions of the design. In addition to these documents, the committee received briefings from DNDO and its federal, state, and local partners that helped to complete its understanding of the GNDA as it currently exists. These briefings are listed in Appendix A.

According to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the GNDA is “a worldwide network of sensors, telecommunications, and personnel, with the supporting information exchanges, programs, and protocols that serve to detect, analyze, and report on nuclear and radiological materials that are out of regulatory control.”1 The GNDA is a complex system of systems involving many U.S. and international organizations whose collective purpose is to reduce the risk of radiological or nuclear terrorist attacks

_____________

1 See http://www.dhs.gov/architecture-directorate. Accessed August 1, 2013.

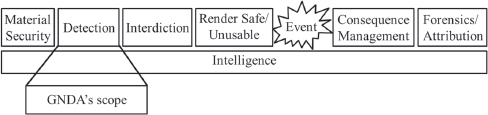

FIGURE 2-1 The nuclear counterterrorism (NCT) operational spectrum is described from the origin or location of radiological or nuclear material through detonation (“the boom”) to forensics and attribution. Within this spectrum, the GNDA’s mission scope occurs between material security (RN material under regulatory control) and interdiction (return to regulatory control).

SOURCE: Modified from National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA; http://nnsa.energy.gov/aboutus/ourprograms/ctcp/nuclearthreatscience. Accessed August 1, 2013).

through detection and reporting capabilities. The GNDA defines detection to include both technical (detection equipment) and nontechnical (an information alert) means.2 The GNDA is often described as having a defense-in-depth structure organized by groups of nuclear detection capabilities distributed across three geographical layers (a layer external to the United States; a transborder layer; and an interior layer) and a fourth crosscutting layer (such as intelligence, coordination, and communication functions).

The GNDA’s detection capabilities are designed and deployed to detect radiological and nuclear material outside of regulatory control. They are not designed to detect an unauthorized nuclear detonation or test. Such capabilities are outside the scope of the GNDA and are the responsibility of other agencies and programs. They were not investigated in this study. The GNDA is one part of the U.S. nuclear counterterrorism (NCT) mission to reduce the risk of nuclear and radiological terrorist or covert host-state attacks. The NCT mission is frequently displayed as a spectrum of operational activities that occur either before or after a nuclear or radiological event (see Figure 2-1). Activities related to the NCT are referenced within this community as “left of the boom” and “right of the boom.” The scope of the GNDA, to detect and report on occurrences of radiological and nuclear (RN) material discovered out of regulatory control, is left of the boom and within the “detection” portion of the spectrum. Interdiction of nuclear material (e.g., recovery of material) is not part of the GNDA’s mission, nor is material security (e.g., physical security of nuclear materials and the facilities that produce them) but both activities interface directly with the GNDA. Furthermore, the scope of the GNDA does not include intel-

_____________

2 See Appendix F for a glossary of terms.

ligence functions such as threat definition. These functions are performed by and shared through the Director of National Intelligence (DNI).3

Within this spectrum, the GNDA’s scope can be considered as being analogous to “bell ringer” systems, such as the worldwide tsunami detection system, that serve to discriminate between false alarms and actual events and provide warnings of real threats to the appropriate partners in actionable time frames (NTHMP, 2013). However, this analogy excludes an important component of the GNDA’s mission that makes it distinct from natural disasters such as tsunamis. The GNDA is preventive and includes two components: (1) deterring an adversary and, if that fails, (2) detecting and reporting of undeterred attempts.

DNDO and its federal partners within the GNDA seek ways to assess the effectiveness of the GNDA against the threat of intelligent, adaptive adversaries—including the effectiveness of deterrence. Deterrence and its characterization as they relate to the GNDA are discussed in Chapter 4.

2.1.1 GNDA Participants

DNDO, in its coordination role for the GNDA, works closely with several federal nuclear security partners, including

• Department of Energy (DOE) National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA),

• DNI,

• Department of Defense (DOD),

• Department of State (DOS),

• Department of Justice, primarily the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI),

• Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC), and

• other DHS agencies including the U.S. Coast Guard, Customs and Border Protection, and the Transportation Security Administration.

However, DNDO does not have the lead role for either designing or controlling the GNDA. In fact, no single agency or entity has a clearly defined lead.

Additional participants in the GNDA include international, federal (in addition to the GNDA partners listed above), state, local, tribal, and territorial entities.4 DHS and DNDO do not have direct authority over these participants. Furthermore, these entities are not obligated to participate in GNDA activities. In many instances these participants might not be aware

_____________

3 P.L. 110-53.

4 See http://www.dhs.gov/architecture-directorate. Accessed August 1, 2013.

that their activities are considered part of the GNDA, and they may not understand the GNDA acronym, mission, or scope. These partners are not as familiar with the term “GNDA” as they are with “preventive radiation and nuclear detection” (PRND) programs and activities that span multiple parts of the federal NCT spectrum (see Figure 2-1).5 International partners are also not obligated to participate in the GNDA. Efforts to work cohesively and within mission goals of the GNDA with other countries are coordinated by a group of federal agencies (as defined by the SAFE Port Act).

The GNDA does not have a central budget. Funding for GNDA-related activities is provided through a variety of federal agencies’ appropriations bills or grants to state and local jurisdictions. Funding for nuclear detection capabilities (detectors, training, analysis, and alerting) is provided directly to GNDA participants usually as part of funding for a larger mission. Since there is no central GNDA budget, there is no central budgetary authority or oversight control.6

2.1.2 GNDA STRUCTURE

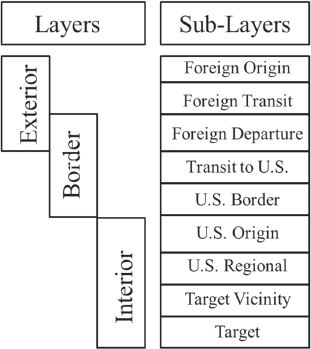

There are two main views of the GNDA structure. The first is the “geographical view” of the GNDA; it is described as a set of three main geographical layers (see Figure 2-2).

The description of each layer can be found on DHS’s website.

• “The interior layer of the GNDA includes all areas within and up to, but not including, the U.S. border. The interior layer focuses on increasing nuclear detection capabilities across the maritime, air, and land pathways and addressing a wide array of potential threats.”7 Under the SAFE Port Act, DNDO is responsible for implementation of the domestic portion of the GNDA.

• “The transit and border layer (trans-border) is composed of transit to the United States from a foreign port of departure or non-port of departure, as well as passing through the U.S. border prior to entering the U.S. interior. This represents the last opportunity to detect radiological or nuclear materials prior to their arrival onto U.S.

_____________

5 The article, “Preventing the Theft of Dangerous Radiological Materials,” by Edward Baldini (2010) describes the Philadelphia Police Department’s PRND activities with DNDO and other federal agencies without mentioning the GNDA. (http://www.policechiefmagazine.org/magazine/index.cfm?fuseaction=display_arch&article_id=2199&issue_id=92010. Accessed August 1, 2013.)

6 This issue has also been identified through Senate hearings (U.S. Congress, Senate, 2010) but no actions have been taken. (http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-111shrg58397/html/CHRG-111shrg58397.htm. Accessed on August 1, 2013).

7 Layered Nuclear Defense: Interior Layer, http://www.dhs.gov/layered-nuclear-defense-interior-layer. Accessed August 1, 2013.

FIGURE 2-2 Geographical view of the GNDA. In this view, the GNDA is described as having three geographical layers (exterior, border, and interior). The crosscutting functions are not shown.

SOURCE: Modified from DHS (2007).

territory, and initiatives in this layer emphasize maritime domain awareness related to preventive radiological/nuclear detection.”8 Although maritime domain awareness is highlighted in this text, land and air transportation pathways are considered part of the GNDA.

• “The exterior layer comprises the foreign origin, foreign transit and foreign departure sub-layers. We improve radiological and nuclear material detection abroad through efforts that encourage foreign nations or regions to develop and enhance their nuclear detection architectures.”9 Under the SAFE Port Act, DOS, DOE, and DOD are responsible for implementation of the exterior portion of the GNDA consistent with international agreements and laws.

• “Cross-cutting efforts focus on programs and capabilities spanning

_____________

8 Layered Nuclear Defense: Trans-border Layer, http://www.dhs.gov/layered-nuclear-defense-trans-border-layer. Accessed August 1, 2013.

9 Layered Nuclear Defense: Exterior Layer, http://www.dhs.gov/layered-nuclear-defense-exterior-layer. Accessed August 1, 2013.

multiple layers and pathways of the GNDA. Efforts undertaken in this layer provide the basis for time-phased deterrence and detection strategies. These elements streamline existing capabilities, improve overall coordination and ultimately seek to enhance radiological and nuclear detection at the federal, state, territorial, tribal and local levels.”10

In the geographical, three-layered view of the GNDA, transportation pathways and detection capabilities are grouped into modalities (e.g., land, air, sea for pathways; passive radiation portals, or handheld sensors for detection capabilities) with combinations of modality pathways and capabilities considered against known aspects of the terrorist threat.11

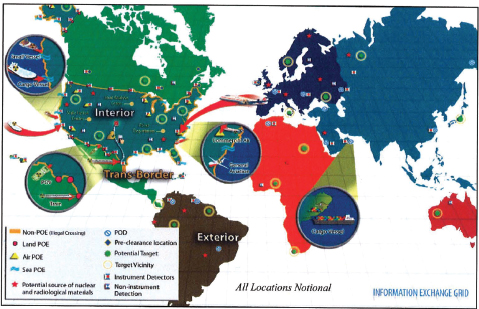

The other view of the GNDA structure is an operational view (OV). A notional diagram of the GNDA OV is shown in Figure 2-3.12 This view, when populated with the specific geographical locations of threats, capabilities, and targets, can provide an intuitive picture of current operational capabilities and redundancies across the GNDA. As was shown in the geographical view, gaps in operational coverage can also be identified and prioritized through threat analysis, and particular routes can be highlighted (e.g., pedestrians traveling from Mexico to the United States between the ports of entry in El Paso and Presidio, Texas). See Chapter 5 for a more detailed discussion on these two views of the GNDA and their corresponding models. The global aspect of the architecture is clear in both views, so it is important to note that threats originating domestically are also included in the GNDA.

2.2 DISCUSSION

This report is not an assessment of how effectively the current GNDA is performing. The committee was not asked to evaluate the DNDO, its partner agencies, or the existing GNDA organizational or budgetary structure. This report addresses the study charge by providing examples of notional metrics and an analysis framework that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the GNDA. However, based on its understanding of the GNDA, the committee identifies several challenges that could affect the ability of

_____________

10 Layered Nuclear Defense: Cross-cutting Efforts, http://www.dhs.gov/layered-nuclear-defense-cross-cutting-efforts. Accessed August 1, 2013.

11 Threat characteristics are determined by the intelligence community. Threat assessment is outside the scope of the GNDA.

12 The committee notes that this notional image is not an OV by the military terms. A military OV is a document that describes each node (e.g., land point of entry, or potential target) and its interaction with other nodes.

FIGURE 2-3 Operational View of the GNDA. In this view, existing threats and targets, transportation pathways, and current detection capabilities are mapped onto their actual geographic locations. This example is notional.

SOURCE: GNDA (2011).

DNDO and its GNDA partners to implement this report’s findings and recommendations.

2.2.1 GNDA Governance

The public laws that created the GNDA do not assign it clear leadership. DNDO is designated as the coordinating entity and is frequently considered responsible for the GNDA (GAO, 2008; Shea, 2008). But there is no defined lead architect—whether an agency, entity, or person—to make decisions about or to be held accountable for design and implementation of the GNDA.

Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, there is no centralized GNDA budget. Funding is provided to multiple agencies for GNDA-related activities through multiple appropriations bills. Actual costs for activities can be difficult to estimate because detection and reporting of radiological and nuclear material out of regulatory control are part of larger missions executed by many partners. This introduces uncertainties and inconsistencies in the annual reported budget values. Without a clear understanding of the costs and the authority to make decisions, prioritization across the GNDA

is very difficult. However, this situation is not unprecedented within the U.S. government.

Other organizations such as the National Earthquake Hazard Reduction Program (NEHRP) have addressed similar challenges. NEHRP is a set of four federal agencies13 with separate budgets: “There is no single congressional appropriation for NEHRP, nor does the NEHRP Secretariat control individual agency budgets, personnel, or activities” (NEHRP, 2008, p. 12). Like the GNDA, NEHRP was established by law (Earthquake Hazards Reduction Act of 1977, as amended, 2004 [P.L. 95-124, 42 U.S.C. §§ 7701 et seq.]14). Well-defined leadership was established by the NEHRP Reauthorization Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-360)15 which established the NEHRP Interagency Coordinating Council (ICC). The ICC oversees NEHRP planning, management, and coordination and has the responsibility of developing the strategic plan. Members of the ICC include the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, the Office of Management and Budget, and the directors of each of the four agencies that compose the NERHP; the ICC is chaired by the Director of NIST. The NEHRP agencies work closely to make decisions that mutually benefit the overall (and overlapping) mission when possible (NEHRP, 2008). The NEHRP strategic plan lists the agencies’ coordinated vision, mission, goals, and objectives, but the implementation is the responsibility of each agency.

2.2.2 Critical Activities at Mission Boundaries

Different federal agencies are responsible for the different activities within the NCT mission spectrum (see Figure 2-1). Critical activities and decisions are made at the boundaries of these missions, which can lead to segmented agency activities and processes. The limited scope of “detection” was noted by J. C. Wyss (2012) in his presentation to the committee: “Nuclear detection is not a distinct event (p. 9).” The segmentation could affect the federal government’s ability to fully consider strategies to combat threats, to fully integrate activities, and to coordinate exercises and lessons learned that cross mission boundaries.

The scope of the GNDA mission is detection of materials out of regulatory control (see Figure 2-1); the mission boundary to the left is “material security,” and the mission boundary to the right is “interdiction.” In the

_____________

13 The four federal agencies are: Federal Emergency Management Agency (http://www.fema.gov/earthquake) of the Department of Homeland Security, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST, http://www.nist.gov/index.html) of the Department of Commerce (NIST is the lead NEHRP agency), National Science Foundation (http://www.nsf.gov/) and the United States Geological Survey (http://www.usgs.gov/) of the Department of the Interior.

sections below, the committee considers activities at each interface focusing on domestic examples to highlight U.S. federal agency involvement. Security of domestic sources of RN material is the responsibility of several federal agencies including USNRC, FBI, and NNSA. Interdiction within the United States is the responsibility of the FBI.

Material Security Boundary

The committee notes that significant progress has been made by the FBI and NNSA on providing training and exercises to secure materials at domestic facilities housing potential radiological dispersion device (RDD) threat material.16Box 2-1 has a detailed discussion on the differences between radiological and nuclear attacks. Tabletop exercises (e.g., the Silent Thunder tabletop series) include participation by the FBI, NNSA, state and local law enforcement, and industrial partners. The exercises are aimed at giving federal, state, and local officials, first responders, and law enforcement critical, hands-on experience in responding to a terrorist attack involving radiological materials (NNSA, 2012a). Communication and coordination on the concept of operations (CONOPS) developed within these multiple exercises can be specific to the state/local or industrial location. The results of these exercises which are focused on the mission of physical security of radiological sources are best shared across the federal mission boundaries (e.g., to include detection of radiological material out of regulatory control) so that they are seamless from the perspectives of state and local entities (see Box 2-1).

Interdiction Boundary

Critical activities occur and decisions are made at the interface of adjacent activities within the NCT mission. Federal responsibilities change hands at these interfaces, for example, the detection—interdiction interface. This could have an unintended consequence of limiting the U.S. government’s choices in responding to a confirmed detection event. Clearly the operational decisions and subsequent actions that occur between confirmation of the detection of a threat material and its interdiction need to be made quickly (e.g., detection of a threat in a truck at a border crossing).

_____________

16 “In the event that terrorists were able to obtain radiological materials and attempt to use them in an attack, NNSA has worked with federal, state, and local officials across the country through a series of tabletop exercises that strengthen first responders’ and law enforcement officials’ ability to detect, deter and prevent a terrorist WMD incident from occurring, as well as emphasize efforts to respond to, mitigate and recover from the effects of such an event. NNSA’s 100th exercise of its kind was held in August” (NNSA, 2012b).

BOX 2-1

Radiological and Nuclear Attacks

Radiological and nuclear attacks are very different. DHS, in conjunction with the NRC, has defined both types of attack:

A radiological attack is the spreading of radioactive material with the intent to do harm. Radioactive materials are used every day in laboratories, medical centers, food irradiation plants, and for industrial uses. If stolen or otherwise acquired, many of these materials could be used in a “radiological dispersal device” (RDD). (NAE/NRC, 2004)

A nuclear bomb creates an explosion that is thousands to millions of times more powerful than any conventional explosive… . The resulting mushroom cloud from a nuclear detonation contains fine particles of radioactive dust and other debris that can blanket large areas (tens to hundreds of square miles) with “fallout.”… The primary obstacle to a nuclear attack is limited access to weapon-grade nuclear materials. Highly enriched uranium, plutonium, and stockpiled weapons are carefully inventoried and guarded. (NAE/NRC, 2005)

A radiological or “dirty bomb” attack employs an RDD that uses means such as chemical explosives, for example, to widely disperse radiological materials. The radiological materials vary in source, isotope composition, and radioactivity level. The United States has many medical and industrial facilities that store and regularly use radiological materials. Because terrorists are more likely to seek sources within the United States to avoid long transportation routes, theft and misuse of radiological sources are serious threats. An RDD attack is listed as one of 15 disasters within National Planning Scenarios (DHS, 2006).

In contrast, a nuclear attack employs weapon-grade nuclear materials (highly-enriched uranium [HEU] and plutonium). The number of facilities storing weapon-grade materials is significantly less than those storing radiological sources. Within the United States, these materials are highly secured at a limited number of sites. Weapon-grade material is also stored at foreign facilities. Because weapon-grade materials are relatively scarce compared with radiological sources and because the impact of a nuclear attack is so large, it is thought that terrorists will attempt to obtain these materials wherever possible. In this case, the threat is not focused on domestic facilities but is considered global. An improvised nuclear device (IND) attack is identified as a scenario distinct from an RDD attack in the National Planning Scenarios list (DHS, 2006).

For the GNDA, these two attack modes represent separate overall architectures (Rosoff and von Winterfeldt, 2007). Preventing nuclear attacks puts an emphasis on securing foreign facilities and detecting nuclear materials en route to the United States. In contrast, preventing RDD attacks puts an emphasis on securing facilities in the United States and possibly establishing detection capabilities at major facilities (e.g., blood or food irradiation facilities). Although the physical security of sources is outside the scope of the GNDA, it has a direct impact on the evaluation of overall risk of a radiological attack.

There are two response options to a confirmed detection of threat material out of regulatory control:

1. The threat materials are returned promptly to control status upon confirmed detection and reporting, and

2. The detected threat materials are allowed to pass “seemingly undetected” to root out covert terrorist cells and networks, which may have the capabilities to transport and accumulate fissile and radiological materials and assemble, place, and detonate a nuclear device or RDD within the continental/contiguous United States.

The first case has been exercised repeatedly by the U.S. government. However, the second case demonstrates the challenge of making a decision about what to do with the detection information. Who would make a decision to not interdict? If it is not interdicted, which mission space does the activity now fall under? One could argue whether or not this scenario is realistic based on current capabilities and policies, but it provides an example in which the structure and responsibilities of the NCT mission space may have an unintended consequence of limiting U.S. government response options.

2.3 COMMITTEE’S OBSERVATIONS

The following observations are made to highlight potential challenges in implementing the committee’s findings and recommendations which appear elsewhere in this report:

OBSERVATION 1: There is no clear lead architect or single entity to make final decisions about or to be held accountable for the design and operation of the GNDA. Furthermore, there is no centrally controlled GNDA budget; GNDA-related detection and reporting activities are intertwined with diverse mission activities across the GNDA federal agencies and do not have specific lines of funding. Thus, there is no single congressional appropriation for the GNDA nor is there a single entity with budgetary control over GNDA activities across multiple agencies.

The GNDA operates via a loosely confederated collection of federal, state/local and tribal programs and activities under what could be considered a “best-effort” budget. This is important to note, because it may not be possible to effectively utilize the results from an analysis framework and measures of effectiveness of the overall GNDA in a way that would change the contributions of participating agencies to the overall budget. This does not imply that developing improved metrics to guide resource decisions and establishing an analysis framework for the GNDA is without purpose.

Establishing a capability to evaluate the GNDA effectiveness can provide useful information to decision makers such as the gap between existing and optimal resource allocation and a measure of the cost of operating the GNDA. The issue of disconnected budgets’ impact on coordination of the GNDA has been highlighted previously.17

OBSERVATION 2: The GNDA operates within a larger nuclear counterterrorism (NCT) mission. Its scope is limited to deterrence, detection, and reporting. When considering how to address and define the GNDA strategy and goals, focusing solely on the detection and reporting mission may limit wider U.S. government actions that span multiple components of the NCT mission space.

It is difficult to segregate actions and strategies focused on deterrence, detection, and reporting from missions of federal agencies (Wyss, 2012). In the sections above the committee provides several examples of the impact of NCT federal mission boundaries on strategic planning and response options.

_______________

17 This issue has been identified through Senate hearings (U.S. Congress, Senate, 2010 Hearing 111-1096) but no actions have been taken. (http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-111shrg58397/html/CHRG-111shrg58397.htm. Accessed August 1, 2013).