New Approaches and Capabilities in Assessment

In addition to changing and adding to what is measured, as was described in previous chapters, assessments can also be improved by changing how traits are measured. Although the Army already employs a well-developed battery of tests, recent and impending advances in assessment methods offer the potential to improve that testing by improving the accuracy of a test, by providing assessments of traits that have not previously been tested (including team-related traits), or by making the tests easier—and thus faster—to administer, making it possible to include additional assessments in the time available.

Many of the workshop participants, speaking generally, noted that many emerging assessment measures tend to focus on more complex tasks, to use simulations more extensively, and to put greater emphasis on more realistic and real-time tasks. These new assessments also gather more data and more types of data, including timing data and longitudinal data, which in turn increases the types of analyses that can be performed.

Two speakers in particular discussed such new approaches and capabilities in assessment. Paul Sackett, who spoke during a panel on the second day, categorized the various approaches to improve assessment and gave a broad overview of current thinking on the sub’ect. The workshop’s keynote speaker, Alina von Davier, discussed current and potential future research at the Educational Testing Service relevant to the next generation of assessments.

A TAXONOMY FOR WAYS TO IMPROVE SELECTION SYSTEMS

Over time, researchers and assessment experts have suggested a large number of ways to improve assessments. To help organize and make sense of the multitude of suggestions, Paul Sackett, a distinguished professor of psychology and liberal arts at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, offered a taxonomy for thinking about ways to improve the quality of selection systems. In his presentation, he also offered a number of specific examples of approaches to improving assessments.

In particular, Sackett drew from a review article he published with a colleague in 2008, which proposed four categories of methods to improve selection systems: (1) identify new predictor constructs, (2) measure existing predictor constructs better, (3) develop a better understanding of the criterion domain, and (4) improve the specification and estimation of predictor-criterion relationships (Sackett and Lievens, 2008). A number of the presentations in the workshop, he noted, had already focused on new predictor constructs—for example, working memory capacity, inhibitory control, and personal agency—so Sackett focused his presentation on the other three categories.

Improving Measurements of Existing Predictor Constructs

In addition to identifying new predictor constructs, another way to improve assessments would be to measure existing predictor constructs better. “We need to think systematically about that,” Sackett said. To encourage the workshop participants to think about how one might begin to improve existing predictor constructs, he offered three specific examples: contextualized personality items, narrower dimensions of personality measures, and use of real-time faking warnings.

Contextualized Personality Items

To begin, Sackett addressed personality assessments. Many personality inventories simply do not provide context, he said. The questions are overly generalized, such as, “Agree or disagree: I like keeping busy.”

But there has been a great deal of work in the area of industrial and organization psychology, Sackett noted, that indicates adding context can greatly improve the predictive ability of assessments (Shaffer and Postlethwaite, 2012). “Just add two words,” he said, “At the end of that item, add ‘at work’: ‘I like keeping busy at work.’ We’re not talking fancy contextualization to a specific job, but very, very generic contextualizations.”

Sackett described the results of a meta-analysis that examined the effect of adding context to assessment items. In particular, the analysis

compared standard personality assessment items with contextualized items—that is, items that had been modified by asking about behavior at work rather than behavior in general. The two types of assessments were compared with supervisory ratings of job performance to determine their correlation with those ratings. The contextualized measures, Sackett reported, reflect the supervisory ratings more accurately. For conscientiousness, for example, the validity of the contextualized measure was 0.30 versus 0.22 for the standard measure. For emotional stability it was 0.17 versus 0.12, for extraversion it was 0.25 versus 0.08, and for openness it was 0.19 versus 0.02. The average validity for the contextualized measures was 0.24 versus 0.11 for the standard measures (Shaffer and Postlethwaite, 2012). Sackett noted that adding context thus doubled the validity of the measures.

Narrower Dimensions of Personality Measures

A variety of researchers have discussed the idea of dividing the Big Five personality traits into smaller, more focused traits. In 2007, for example, DeYoung and colleagues suggested splitting each of the Big Five traits into two:

- neuroticism [emotional stability] becomes volatility and withdrawal,

- agreeableness becomes compassion and politeness,

- conscientiousness becomes industriousness and orderliness,

- extraversion becomes enthusiasm and assertiveness, and

- openness to experience becomes intellect and openness.

Intuitively the divisions make sense, Sackett said, and there is also some evidence that the way the splits are made is not arbitrary. In particular, he described one study that indicated that such splits may be useful in terms of their predictive power.

In 2006, Dudley and colleagues carried out a meta-analysis of how well global measures of conscientiousness predict task performance versus the predictive power of four conscientious facets: achievement, dependability, order, and cautiousness. Industrial and organizational psychologists generally accept that, among the various measures of personality, conscientiousness is the best predictor of task performance, Sackett noted. The meta-analysis found that the validity of conscientiousness as a predictor of task performance—that is, how well it predicted performance—was driven mainly by the achievement and dependability facets of conscientiousness. The facets of order and cautiosness did not contribute, according to Sackett. “So to the extent that you spend half of your items trying

to cover the full range [of conscientiousness], you’re including stuff that, at least for prediction in work settings, doesn’t carry any freight,” Sackett said. “It’s not useful.”

Furthermore, the two facets predicted different aspects of work success. “The achievement piece receives the dominant weight if you’re predicting task performance, while dependability receives the dominant weight in predicting job dedication and the avoidance of counterproductive work behaviors,” he said. This sort of nuanced approach to testing could be valuable in pre-employment assessments.

Use of Real-Time Faking Warnings

In personality assessments, there is always concern that people will attempt to manipulate impressions to convey themselves more favorably than reality. This, of course, produces less valid test results.

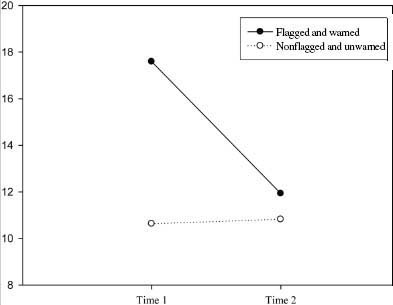

One approach to dealing with this problem is to use responses to early items in order to assess faking and then intervene with a warning to those who appear to be skewing their answers. “You’ve got to word [the warning] really carefully,” Sackett cautioned, to avoid making accusations about lying or cheating. “You say, this is a pattern that is typical of people who are trying to improve their performance; we’re going to take you back to the top and encourage you to respond honestly.”

One study in which Sackett was involved looked for “blatant extreme responding,” something that generally appears in only a small percentage of test takers. After one-third of the items had been administered in a test given to managerial candidates, a warning was issued to those who were exhibiting this blatant extreme responding. The rate of extreme responding was halved—from 6 percent to only 3 percent—after the warning (Landers et al., 2011).

A second study involved an assessment for administrative jobs in China (Fan et al., 2012). A number of socially desirable items were included relatively early in the test, and a warning was given to those people who were exceeding a certain threshold.

The result, as shown in Figure 5-1, demonstrates that those with low impression-management scores continued to obtain low scores as the assessment progressed. But those with high impression-management scores produced markedly lower scores after receiving the online warning.

Better Understanding of the Criterion Domain

Another way to improve assessments is to develop a better understanding of the criterion domain. Sackett offered two examples of this approach: predictor-criterion matching and identification of new criteria.

FIGURE 5-1 The effect of real-time faking warnings.

SOURCE: Fan et al. (2012).

Predictor-Criterion Matching

People tend to wonder whether test X or construct X is a good predictor, Sackett said, but that begs the additional question: A good predictor of what? In particular, there is a tendency to think about “performance” as a single thing and thus to ask whether a test is a good predictor of performance. The industrial and organizational psychology literature, he said, is full of this sort of thing. For example, it is common to claim that general cognitive ability is the best predictor of job performance, he added, but that really depends on what facet of job performance one cares about.

As an example, Sackett showed some results from the classic Project A study by the U.S. Army (McHenry et al., 1990). Table 5-1 shows validity scores for three measures—general cognitive ability, need for achievement, and dependability—and three performance domains—task performance, citizenship, and counterproductive work behavior. (The latter are labels applied to the performance domains by Sackett, not by the original researchers.) Task performance is simply how well a person completes assigned tasks, Sackett said. Citizenship measures such things as con-

TABLE 5-1 Validity Scores for Three Measures (Predictors) and Three Performance Domains (Criteria)

|

|

|||

| Criteria | Predictors | ||

|

|

|||

| General Cognitive Ability |

Need for Achievement |

Dependability | |

|

|

|||

| Task Performance | .43 | .11 | .11 |

| Citizenship | .22 | .30 | .22 |

| Counterproductive Work Behavior | .11 | .18 | .30 |

|

|

|||

SOURCE: Sackett presentation.

tributing extra effort, helping others, and supporting the organization. Counterproductive behavior is self-explanatory. (In Table 5-1, the validity scores for counterproductive work behavior are reverse-coded so that the direction of the correlations remains the same for all three domains.)

“Is general cognitive ability the best predictor? Yes, it’s the best predictor of task performance. It beats need for achievement and dependability.” Sackett added that it is clearly not the best predictor of citizenship or counterproductive work behavior. So it is important to think carefully about what one is trying to predict, he concluded, because using the wrong criterion in correlation computations may nullify the results.

As another example, Sackett described a study of a situational judgment test used for medical school admissions in Belgium. A subject is shown a video of a doctor interacting with a patient, the video is stopped, and the subject is asked what should be done next. It is a way of testing a subject’s interpersonal skills more than anything else. It was found that this situational judgment test had predictive power in medical schools that had a “whole person” focus but not in those schools that took a “scientific” focus. Similarly, the test predicted performance in internships and in rotations but not in academic courses (Lievens et al., 2005).

“If you think about it,” Sackett said, “that’s what it should do. But if you don’t think straight, and you just grab the overall GPA [grade point average] as a criterion measure, you’ll reach a very different conclusion as to whether this test has any value.” Thus, it is important to think carefully about what a test is being used to predict and what makes sense, conceptually, for a test to predict.

Identification of New Criteria

Sackett’s second approach to better understanding of criterion domains is to identify new criteria. For example, Pulakos and colleagues (2000) developed the notion of adaptive performance at work, developed measures of it,

and then examined predictors of it. This approach has become quite popular recently, Sackett said. Employers are saying things like, “The world is changing. I want people who can quickly change. What can we do?” Sackett noted that a similar strategy could be applied to many other domains, and he suggested two in particular: teamwork performance and crisis performance.

There are two different strategies for dealing with new factors like this, Sackett said. One is to develop methods to measure factors directly in job applicants—to put people in simulations where things change and observe if they can adapt or to assess their teamwork skills. In this case, the new construct is put on the predictor side, where adaptability or some other new construct is used as a predictor of performance.

Sometimes, though, it may not be feasible to develop or conduct the necessary assessments to use the construct as a predictor prior to employment. In that case, Sackett suggested that the construct can be used as a criterion instead. Once someone is working in the job, measures can be developed to assess how well he or she adapts to change or deals with teamwork, and then one looks for predictors that can be used to predict these new measures of performance.

Improved Understanding of Predictor-Criterion Relationships

According to Sackett, the final route to better assessment systems is to improve one’s specification and estimation of predictor–criterion relationships. He offered three specific examples: profiles of predictors, interactive relationships, and nonlinear relationships.

Profiles of Predictors

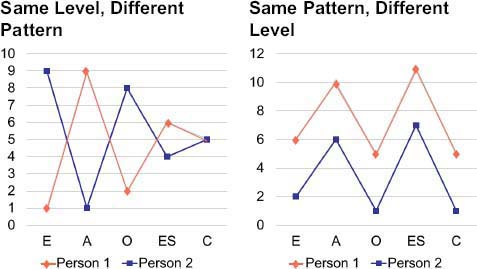

A set of predictors, such as the Big Five personality traits, can be thought of as a collection of numerical values, Sackett suggested, and one can then ask, what about that set of predictors is most predictive of a certain criterion? In 2002, Davison and Davenport developed a technique that focuses explicitly on criterion-related profiles. This approach separates the variance attributable to the level (or mean elevation) of the predictors and the profile (or deviations from the mean) of the predictors.

The difference can be seen by looking at the two graphs in Figure 5-2, each of which shows the Big Five personality trait profiles of two people. The two people in the graph on the left have profiles that are radically different, but they have the same mean level, if one thinks of the profile in terms of a composite value, where a high score on one attribute compensates for a low score on the other. By contrast, the two people in the graph on the right clearly differ substantially in level but are identical in profile. “The conceptual question is, where does the predictive power

FIGURE 5-2 Variance in level of personality measures (right) versus variance in personality profile (left): A notional example.

NOTE: A = agreeableness; C = conscientiousness; E = extraversion; ES = emotional stability; O = openness.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Shen and Sackett (2010).

come from?” Sackett asked. “Does the predictive power come from level, or does the predictive power come from profile?”

When Sackett and his colleague examined how the Big Five personality traits predicted citizenship and counterproductive behavior in a group of 900 university employees, they found that the predictive power for citizenship came completely from the profile level. For counterproductive behavior, however, both the level and the pattern were important predictors (Shen and Sackett, 2012). “I want to suggest that we think about things like this,” he said.

Interactive Relationships

Sackett’s second example of improving predictor-criterion relationships involved interactive relationships among traits. It is a truism in work psychology, Sackett said, that performance is a function of ability times motivation. “You can have all the ability in the world, but if motivation is zero, nothing is going to happen. You can have all the motivation in the world, and if ability is zero, nothing’s going to happen.”

While most psychologists study the independent contributions of ability and motivational traits, Sackett suggested that perhaps they should be looking at their interactions. The published findings in this area are

a mixed bag, he said. Some studies find some evidence of interactive relationships, some do not (for a review, see Sackett et al., 1998). But he suggested it is important to think clearly about the issue and to examine the possibility of predictors working together interactively.

Nonlinear Relationships

As his third example, Sackett suggested that it may be worth considering the possibility of nonlinear relationships between predictors and criteria. Psychologists usually model predictor-criterion relationships as linear, and there is good support for this in the ability domain, he said. However, it seems to be a questionable assumption in other domains.

To illustrate, Sackett described a dissertation in development by one of his students. Using raw data on 117 samples of Big Five personality trait performance relationships, the student is examining the relationships between the personality traits and various criteria, such as job performance. One example is the relationship between conscientiousness and an overall job performance measure.

More conscientiousness is better up to a point, but at some point conscientiousness leads to rigidity, and more of it is not better for job performance. Thus modeling the relationship of conscientiousness with performance as linear may misrepresent reality.

The data show something similar for sociability versus overall job performance. Again, more sociability is better until it is not. At some point, being more sociable starts to hurt job performance. However, when the data are analyzed more carefully, Sackett cautioned, there is more to it than may first appear. By coding which types of jobs require a great deal of interaction with other people and then looking separately at jobs with high interaction and low interaction, Sackett’s student uncovered a significantly different picture. For those jobs where interacting with other people is a key part of the job, he found that more sociability is always a good thing, and there is never a point where the graph turns downward. By contrast, for jobs in which personal interaction is not a key component, too much sociability is very clearly a bad thing, and the graph turns down sharply after a certain point.

The bottom line, Sackett concluded, is that it pays to look more closely at predictor–criterion relationships and to not be too quick to assume that a simple linear relationship accurately describes reality.

PSYCHOMETRICS FOR A NEW GENERATION OF ASSESSMENTS

In the workshop’s keynote address, Alina von Davier, a research director at the Educational Testing Service (ETS) and leader of the

company’s Center for Advanced Psychometrics, provided an overview of the coming generation of assessments and then discussed in detail one particular area of research, exploring the use of collaborative problem-solving tasks to assess cognitive skills, under way at ETS.

A Taxonomy of the New Generation of Assessments

One of the factors driving the development of new assessments, von Davier observed, is the change in how people learn and work. For example, education is being redefined by complex computer-human interactions, intelligent tutorials, educational games, adaptive feedback, and other technology-driven innovations, but educational assessments have not kept up with these changes. “We [ETS] are the largest testing organization,” she said, “and we have to think about how we can bridge this void between educational practice and educational assessment.” To do so, she said, test makers will need to understand how to use the advances in technology, statistics, data mining, and the learning sciences to support the creation of a new generation of assessments. ETS has just begun to investigate the psychometric challenges associated with these types of assessments. It has also been looking into ways of collaborating with colleagues from other fields, such as artificial intelligence, cognitive sciences, engineering, physics, and statistics.

von Davier then discussed the various ways in which new and coming assessments differ from previous assessments, organized into a number of categories.

The first category was assessments that represent new types of applications. There are, for instance, assessments of skills that have not commonly been assessed in the past, such as group problem solving. There is also a greater interest in assessments that provide diagnostic and actionable information and a greater emphasis on noncognitive measures. Furthermore, there are assessments aimed at different age groups, such as younger children.

Many new types of assessment tasks are also being developed. Some of the most interesting assessments in this second category, von Davier said, use various complex tasks, such as simulations and collaborative tasks. People are working on using serious games as a context for the assessment and, eventually, as an unobtrusive way to test. And there is research on the iterative development of tasks, where the task itself is developed over time to match the test-taker’s ability.

A third category is new modes of assessment administration. Among these are continuous testing and distributed testing, both of which are already in use. ETS now has tests that are administered in an almost continuous mode, she said. “They bring with them interesting challenges,

from the measurement point of view, from the development-of-items point of view, and from the statistical analysis point of view.” Distributed testing, she explained, refers to a formative type of assessment in which different tests are administered over a period of time. Another mode of administration being explored is the observational rating of real-time performances. And the future will also see a greater use of both technology and interactivity, she suggested.

A fourth way in which new assessments differ from existing ones is in the stakes of assessment. Many of the new assessments are being applied differently in society, she said. More and more often people are taking into account economic issues in test-driven decision making. For example, is it more cost-effective to use tests to improve selection or to spend less on tests and more on training? This sort of economics-driven decision will become increasingly common in the future, von Davier predicted.

Finally, von Davier said, the new generation of assessments will differ from the previous generation in the type of data they produce, both their process data and their outcome data. In the past, for example, tests measured results from one point in time (providing discrete data), but in the future, von Davier believes, more and more tests will be longitudinal in nature (providing continuous data). Thus, the data will have a time element. She imagines tests in the future that will produce data from frequent or continuous test paradigms. There will be outcome data from complex tasks, simulations, and collaborations, all of which will produce very different types of data than tests based on classic item response theory, she explained.

Perhaps even more challenging will be the process data that are collected: detailed information about the processes that the students went through as they carried out their complex tasks, simulations, and collaborations. There will be such things as timing data and eye tracking data.

What will be quite interesting from a statistical point of view, von Davier said, is that there will be an increased mixture of continuous and discrete data. For example, ETS has started to use automatic scoring engines, which can generate continuous scores. In the past, test scores have generally been discrete. “We will need to handle both types of data, continuous and discrete, in the future,” she said.

These new types of assessments will require consideration of how to fulfill traditional assessment requirements such as reliability, validity, and comparability. In particular, von Davier listed the following issues:

- What does it mean to have a reliable test that contains complex tasks? How can we define and elicit the right evidence from the process data?

- How long should a task be so that the process data are rich enough to allow for the intensive and dependent longitudinal models?

- How many tasks are needed for a reliable assessment?

- What is the best way to evaluate the validity of an assessment? What type of data should be collected for a predictive type of study?

- How can one construct complex problems that differ from one administration to the next but that are still comparable? In other words, how can we rethink the notion of test equating?

Assessing Cognitive Skills Through Collaborative Problem-Solving Tasks

The new Center for Advanced Psychometrics at ETS, which officially started on January 1, 2013, under von Davier’s leadership, is intended to focus on this next generation of assessments through research and development projects, she explained. To begin, it will investigate new types of tasks, simulations, and game-based assessments. To illustrate the sorts of new assessments that are coming—and the challenges that they pose—von Davier described one particular research direction that has begun at the new center.

At ETS, von Davier and her group are exploring how to use collaborative problem-solving tasks to assess cognitive skills. The research ideas discussed in her workshop address are also discussed in a recent paper (von Davier and Halpin, in press). A valid assessment reflects the way people learn and use the skills that are being assessed, she said, but traditional assessments have generally ignored the fact that much learning and work today is done in collaboration. Collaborative problem-solving tasks are intended to capture this aspect of learning and work.

One question she faced in working on such tasks was how to define success in this context. Among the several possibilities, she noted, is that success could be defined as a group of individuals performing better than each individual alone. Or it could be defined as the group performing a task faster than the individuals could do it alone. In her work, she said, she has used the former definition of a successful collaboration.

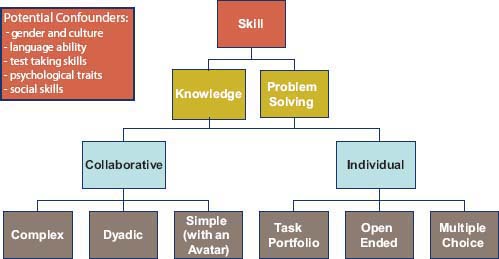

With a diagram, von Davier sketched out a framework for how one might assess cognitive skills using collaborative problem-solving tasks (see Figure 5-3).

The traditional assessments are indicated on the right-hand side of the figure. “That is what we are doing right now,” she said. “We have a particular skill, where we try to measure both knowledge and problem-solving in isolation.” These are assessed using multiple-choice, open-ended, and portfolio tasks. To advance assessment, von Davier’s idea is to add a collaborative task that measures the same skill (e.g., science)

FIGURE 5-3 A framework for assessing cognitive skills with collaborative problem solving.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from von Davier and Halpin (in press).

but in a way that is more reflective of how people typically learn and work today. von Davier said that her group is considering several types of tasks to carry out such assessments: simple tasks using an avatar in place of another person, dyadic tasks with two members on a team, and complex tasks that are carried out in a multiuser environment similar to what is used in commercial games. “The question is, how do you elicit the information you need for the measurement from those tasks? We are not quite there yet.”

The tests in development will be used to measure cognitive skills only, von Davier said, and other skills—communication skills, collaboration skills, and so on—will be considered as potential confounders. That does not mean that these potential confounders are not important, she added; it simply means that she has chosen, at this stage, not to include them in the measurement model. “It is one way to build an assessment. I am not claiming that this is the best way, but I believe that this is something I know how to do. I think that matters, given that we don’t have anything except the use of process data for the measurement of skills.”

Data and Scores

A collaborative problem-solving assessment can produce both process and outcome data, von Davier noted. The process data offer an insight into the interaction dynamics of the team members, which is important

both for defining collaborative tasks and for evaluating the results of the collaboration.

Previous research has suggested both that people behave differently when they interact in teams than when they work alone and that team members’ individual domain scores might not correlate highly with the team’s outcome. The latter is a very interesting hypothesis, von Davier said, and one that could be investigated closely using the framework for the assessment mapped out in Figure 5-3. By assessing the differences between the individual problem solving and collaborative problem solving, she said, one could generalize several scores instead of the single total test score that is usual. “In this situation,” she said, “we might have a score obtained in isolation, a score obtained in collaboration, and the team score.”

Interdependence and Dynamics

In a collaborative problem-solving assessment, von Davier observed, the interactions will change over time and will involve time-lagged interrelationships. Thus, supposing there are two people on a team, the actions of one of them will depend both on the actions of the other and on his or her own past actions. To be beneficial, the statistical models used should accurately describe the dynamics of the interactions.

von Davier believes that the dynamics, which are defined by the interdependence between the individuals on the team, could offer information that could be used to build a hypothesis about the strategy of the team. For example, by analyzing the covariance of the observed variables (the events), one might hypothesize that an unknown variable, such as the team’s strategy type, explains why the team chose a particular response and avoided the alternative.

Modeling Strategies for the Process Data

There are a number of modeling strategies available to use on the process data, von Davier said. Few of them come from educational assessment, however, so they must be adapted from other fields. The modeling strategies include dynamic factor analysis, multilevel modeling, dynamic linear models, differential equation models, nonparametric exploratory models such as social networks analysis, intravariability models, hidden Markov models and Bayes nets, machine learning methods, latent class analysis and neural networks, and point processes—which are stochastic processes for discrete events. The last of these strategies is what von Davier is using now.

Modeling Strategies for the Outcome Data

There are three categories of outcome data that are produced by an assessment of collaborative problem-solving tasks: data on individual performance, data on group performance, and data on the contribution of each individual to the group performance. It is well known how to deal with the first, von Davier noted, and there are straightforward ways of dealing with the second as well, simply by assessing, for instance, whether the group solved the problem or not. But dealing with the third type of outcome data is a challenge. “That is a work in progress,” she said. “We are trying to integrate the stochastic processes modeling approach with the outcome data approach.”

Among the models they are considering applying to outcome data are what von Davier referred to as item response theory–based models. She explained that she meant models that use the same type of rationale that is used in response patterns. Another possibility is using student/learner models from intelligent tutoring systems: “I am open to suggestions from anyone who might have other ideas,” she offered.

The Hawkes Process

To analyze the data from collaborative problem-solving tasks, one of the approaches that von Davier and her colleague Peter F. Halpin from New York University are considering is the Hawkes process, which is a stochastic process (including random variables) for discrete events that can easily be extended to a multivariate scenario such as multiple team members.

The idea behind the Hawkes process is that each event stream is a mixture of three different event types. There are spontaneous events, which do not depend on previous events. “Some member of the team just out of the blue has an idea and puts it on the table.” Then there are self-responses, which are events that depend on their own past. Perhaps, for instance, one individual has several versions of the same idea. But the third event type is the one that really interests von Davier’s team, she said. She described it as “other responses” [responses to others]—events that depend on another person-event stream’s past. This is where the modeling of the interactions between two individuals or between the team and an individual takes place.

The Hawkes process, she explained, estimates which events are most likely to belong to each of these three types, based on a temporal structure of the data, that is, based on event times (Halpin and De Boeck, 2013). “We have time-stamped events: Person X said this, person Y said that. This goes on for the entire half an hour of the collaborative problem-solving

task. We have the time, and we have the event itself.” Von Davier added that her team is now working on using the Hawkes process to analyze the data from collaborative problem-solving tasks.

Possible Approaches for Outcome Data

In the final part of her address to the workshop, von Davier said that she is seeking ways to integrate the models for process data with the outcome data. One idea her team is developing goes further with the Hawkes processes to assign an assessment of correct or incorrect outcome to each event. In other words, they are trying to build what is called a “marked Hawkes Process,” where a “mark” is a random variable that describes the information about each event or interaction (such as noting whether the outcome was correct or incorrect). “Then we can incorporate it [the assigned mark] into the Hawkes process that describes the interactions.” This work is still in development, she said, and while her team has already obtained promising results, it needs to be applied to expanded datasets.

von Davier’s team is also looking at an extension of item response models. The idea is to condition the probability of a successful response from a person not just on the ability of the person, as is traditionally done in item response theory, but also on the response patterns from all the group members. “That is where the challenge comes in,” she said. “How can you take into account the sequence of response patterns over time?”

In the future, von Davier indicated, scientists from her center will pursue research in several other directions as well. They will study the best way to model process data from interactive tasks and from complex tasks administered in isolation, such as simulations and educational games. They will also investigate ways of maintaining task comparability and ensuring the fairness of a complex assessment over time. Some of the research projects will target other challenges of the new assessments she listed in her taxonomy.

In the discussion following von Davier’s keynote address, there was an extensive back-and-forth conversation about outcome criteria and how to code those criteria. Committee member Patrick Kyllonen began by describing a dataset at the National Board of Medical Examiners that contains medical challenges in which physicians are faced with a set of symptoms and then asked to make a judgment or decision. It is interactive, with the physician following a virtual case is which he or she is presented with the relevant information and then, at various points, asked to make a decision about what to do next.

The physicians’ performance is judged in two different ways. One approach simply looks at the outcome: Did the physician make the correct diagnosis or not? In the second approach, experts go through the process data and make a judgment about each decision. An analogy would be playing a chess game in which experts evaluated every move on whether it was a good move or a bad move. “It is a real data mining approach versus a more theoretical approach,” Kyllonen explained.

In other realms, he observed, data mining approaches have generally proven to be stronger, and they have tended to win out over the more theoretical approaches. He then asked von Davier which of the approaches might be more fruitful for coding the results of the collaborative problem-solving tasks. Would it be the data mining approaches, which have beat out the expert judgment approaches in fields from Google’s Internet searches to playing chess, or would it be the more evaluative, theoretical approach?

Google’s data mining efforts are so successful, von Davier pointed out, because there is so much data to mine. “How many collaborative problem-solving tasks can we put in an assessment? … If I can put in only one, and if that will go for 30 minutes, then probably the chain in my process data would be maybe 100, if I am lucky.” Thus the data mining would probably not tell her much about that particular situation, and the expert judgment approach would be more useful. “However, if I am able to obtain data, if I can get multiple teams, and if I can get sufficient data to test them, then the answer is positive. I think data mining will have a strong impact on what we do.”

In reality, she continued, she is looking for a combination of the two approaches for two reasons. First, she is unlikely to access sufficient data for the procedures to be stable. And, second, “We always like theories. What we will probably be using the data mining for would be to help us construct our theories and replace the expert knowledge.”

James Jackson, a member of the National Research Council’s Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences, noted that, in general, some tasks differ in whether there is a successful outcome or not and some tasks differ according to their degree of elegance. In a programming task, for example, it is not simply whether one creates a program to do what it needs to do; the issue of elegance also plays a role. This quality of elegance, he suggested, might provide more variation with which to understand how well people are performing a task.

von Davier agreed, adding that this is very close to something her team is trying to do. “There are examples when, say, a very good sports team loses a game. At the end of the game, everybody would say, they played beautifully, and they still lost.” What she hopes to be able to do with the Hawkes model is to capture that beautiful interaction. “I think that is where the Hawkes models actually can help because of the

way they classify the type of interactions” she continued. For example, one team might have solved the problem and also worked really well together, and the process data along the way would show that. Then there might be another team that also solved the problem, but each of its two members referred only to their own past proposals or ideas during their problem-solving sessions. “That will be an example of a successful solving of the problem, but we will have evidence that the collaboration was not working as well.”

Invited presenter James Rounds noted that there is an area of psychotherapy research on process models in which they do similar coding. One of the reasons why there is not more research in the field, he said, is that it costs a lot of money to do the coding. Todd Little, a presenter from the workshop’s first panel, suggested one way to address the challenge of coding is to plan for missing data. For more information on Little’s ideas

In his presentation during the workshop’s first panel, Todd Little of the University of Kansas in Lawrence, mentioned the value of missing data techniques in various types of analyses, although he did not go into detail at that point. Later, at various points during the two-day workshop, Little and other attendees offered more detailed suggestions for how missing data techniques could be put to work in research and assessment.

Missing data techniques are ways to deal with data that are missing from a study (for reviews, see Enders, 2010; Graham, 2012; van Buuren, 2012). The data can be missing for various reasons, such as survey participants may choose not to answer certain questions or members of a group chosen to participate in a study may fail to take part altogether. Researchers have developed a number of ways to deal with missing data, such as inserting questions into a survey that are designed to characterize those subjects who fail to answer particular questions—out of discomfort with the subject of a question, for example—and thus allow the imputation of plausible answers to passed-over questions that would yield unbiased estimates of the parameters of any statistical model fit to the post-imputation dataset.

Following James Rounds’ presentation, “Rethinking Interests,” Little commented that missing data techniques could have been useful in a longitudinal study that Rounds described. A number of participants had dropped out over time, Rounds noted, and Little commented that it was “probably a selective drop-out process.” That is, some types of participants were more likely to drop out than others. Little explained that one of the benefits of “modern approaches for treating missing data is that we can, through some clever work, get auxiliary variables into [an] analysis model that would be predictive of that selective process.” Then, having characterized which subjects were likely to drop out, it would be possible to use the full-information maximum likelihood estimation—or some other modern missing data technique

about the utility of missing data, see Box 5-1, which summarizes several potential applications in research and assessment.

Committee member Georgia Chao said she is facing similar coding challenges in research she is doing with emergency medical teams. Not only is it necessary to have subject matter experts who know about team processes and can code what is going on in the teams but it is also necessary to have subject matter experts in medicine who code the performance of the team.

“It is not always as simple as, ‘Does the patient live, or does the patient die?’ We [reviewed cases and] were surprised when the medical people said, ‘Oh, this is a great case.’ We looked and said, ‘But the patient died.’ They said, ‘Yes, but they did everything correctly. They diagnosed it correctly, they gave the right kinds of drugs.’ Patients die for all kinds of reasons, so that doesn’t drive the success or failure of an event.” Coding

such as multiple imputation—to see what the survey response would have looked like without the missing data.

Little referred to another way to use missing data techniques as a “planned missing data design,” in which different questions are omitted from different participants’ surveys in a carefully structured way—thus creating missing data—and then modern missing data techniques are used to reconstruct the survey as if every subject had answered every question.

One potential application in research might examine whether new constructs provided incremental validity to established constructs, Little suggested. “It would be a very easy thing to create a multiformed, planned missing data design,” he said. Different individuals would be tested on different constructs, he explained, and one could have a set of variables that could be used to examine all constructs in one big multivariate model, to see if incremental validity is obtained from any of the constructs, above and beyond what is already being measured.

Little also suggested that planned missing data designs could help in studies such as those described by Alina von Davier that collect a great deal of intensive data through the use of observers to code what they observe. He referred in particular to an example that von Davier had offered of coding every interaction in a basketball game. With a planned missing data design, he said, “you can randomly assign who looks at which frame of the basketball game, and then, with the right kind of overlap, you can collect the kind of data you want in a much more efficient way, and not have all of that extra time and energy being spent trying to get everybody to watch every interaction and code every interaction.”

Finally, Little suggested that planned missing data designs could be used to collect data more efficiently in the large batteries of tests used to assess personnel. Such intensive tests lead to fatigue and other factors that undermine their validity, he said, and the problem could be avoided, or at least ameliorated, with a planned missing data assessment protocol. “From that perspective, these [missing data] designs are the more valid, ethical way to go.”

accurately requires being able to code a number of different aspects about what teams do, and that is difficult, Chao acknowledged.

Chao commented that a similar challenge faces the Army. “We [the Army] have platoons that go out. They do everything correctly, and yet the mission fails. What do we do to try to make that not happen again? It speaks to the criterion problem and how complex it is going to be in terms of looking at multiple levels of issues to consider.”

Gerald Goodwin, of the U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, emphasized that to really know whether a particular decision is good or bad, it is necessary to see that decision in the context of an overall strategy. As is the case with chess, it can be difficult to tell whether a move is good or bad without knowing how it fits with other moves in following an overall strategy. “It is not as simple as a correct or incorrect [move] or good or bad [move]. It could be any number of things. It is an indicator of a deeper sequence of performance that you are trying to capture, which is representing some level of skill that is the latent aspect that you are actually trying to estimate.”

Davison, M.L., and E.C. Davenport, Jr. (2002). Identifying criterion-related patterns of predictor scores using multiple regression. Psychological Methods, 7(4):468-484.

DeYoung, C.G., L.C. Quilty, and J.B. Peterson. (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5):880-896.

Dudley, N.M., K.A. Orvis, J.E. Lebiecki, and J.M. Cortina. (2006). A meta-analytic investigation of conscientiousness in the prediction of job performance: Examining the intercor-relations and the incremental validity of narrow traits. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1):40-57.

Enders, C.K. (2010). Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Fan, J., D. Gao, S.A. Carroll, F.J. Lopez, T.S. Tian, and H. Meng. (2012). Testing the efficacy of a new procedure for reducing faking on personality tests within selection contexts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(4):866-880.

Graham, J.W. (2012). Missing Data: Analysis and Design. New York: Springer.

Halpin, P.F., and P. De Boeck. (2013). Modelling dyadic interaction with Hawkes processes. Psychometrika DOI: 10.1007/S11336-013-9329-1. Published online only. Available: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11336-013-9329-1#page-1 [August 2013].

Landers, R.N., P.R. Sackett, and K.A. Tuzinski. (2011). Retesting after initial failure, coaching rumors, and warnings against faking in online personality measures for selection. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1):202-210.

Lievens, F., T. Buyse, and P.R. Sackett. (2005). The operational validity of a video-based situational judgment test for medical school admissions: Illustrating the importance of matching predictor and criterion construct domains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3):442-452.

McHenry, J.J., L.M. Hough, J.L. Toquam, M.A. Hanson, and S. Ashworth. (1990). Project A validity results: The relationship between predictor and criterion domains. Personnel Psychology, 43(2):335-354.

Pulakos, E.D., S. Arad, M.A. Donovan, and K.E. Plamondon. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(4):612-624.

Sackett, P.R., and F. Lievens. (2008). Personnel selection. In S.T. Fiske, A.E. Kazdin, and D.L. Schacter (Eds.), Annual Review of Psychology (vol. 10, pp. 419-450). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews.

Sackett, P.R., M.L. Gruys, and J.E. Ellingson. (1998). Ability-personality interactions when predicting job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(4):545-556.

Shaffer, J.A., and B.E. Postlethwaite. (2012). A matter of context: A meta-analytic investigation of the relative validity of contextualized and noncontextualized personality measures. Personnel Psychology, 65(3):445-493.

Shen, W., and P.R. Sackett. (2010). Predictive Power of Personality: Profile vs. Level Effects Predicting Extra-Role Performance. Presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Conference, April, Atlanta, GA.

Shen, W., and P.R. Sackett. (2012). The Relationship of Big Five Personality Profiles to Job Performance. Presented at the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Conference, April, San Diego, CA.

van Buuren, S. (2012). Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

von Davier, A.A. and P.F. Halpin. (in press). Collaborative Problem Solving and the Assessment of Cognitive Skills: Psychometric Considerations. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. Upon publication, available: http://search.ets.org/researcher [August 2013].

This page intentionally left blank.